ANN-Based Online Parameter Correction for PMSM Control Using Sphere Decoding Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Recent Advances in ANN-Based PMSM Control

1.2. Justification for SDA Selection

1.3. Contribution of This Study

- A data-generation framework using Long Prediction Horizon Finite Control Set MPC (LPH-FCS-MPC) under a wide range of parameter mismatch scenarios.

- A low-feature feedforward ANN estimator trained to capture flux and inductance mismatch effects using simple current-based features.

- Online integration of the ANN with the predictive controller to update parameters, reducing THD and preserving stability even under significant mismatch.

- Runtime profiling and analysis demonstrating the computational efficiency of the proposed ANN estimator.

2. Feedforward ANN-Aided LPH FCS-MPC System Formulation

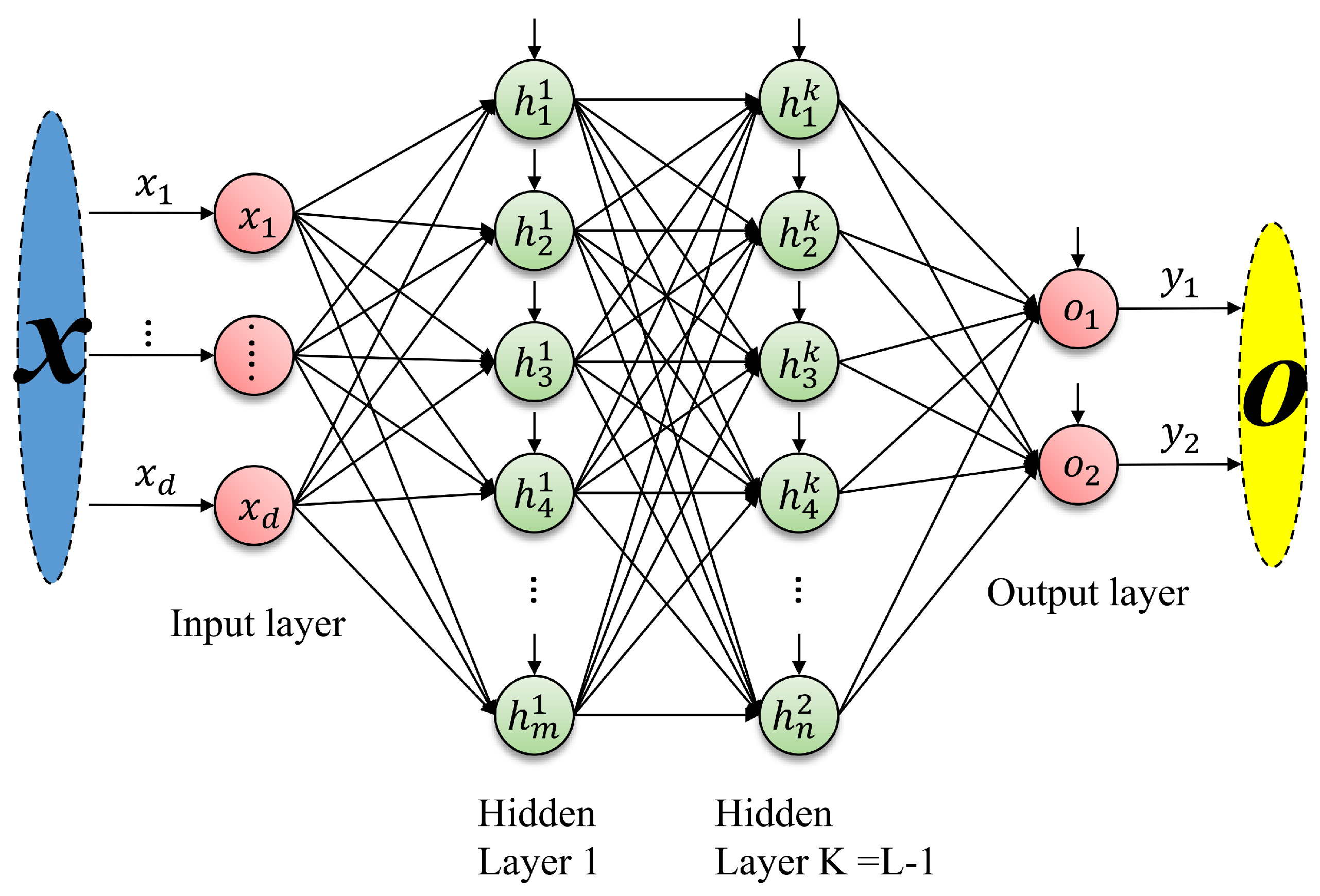

2.1. Feedforward Neural Networks

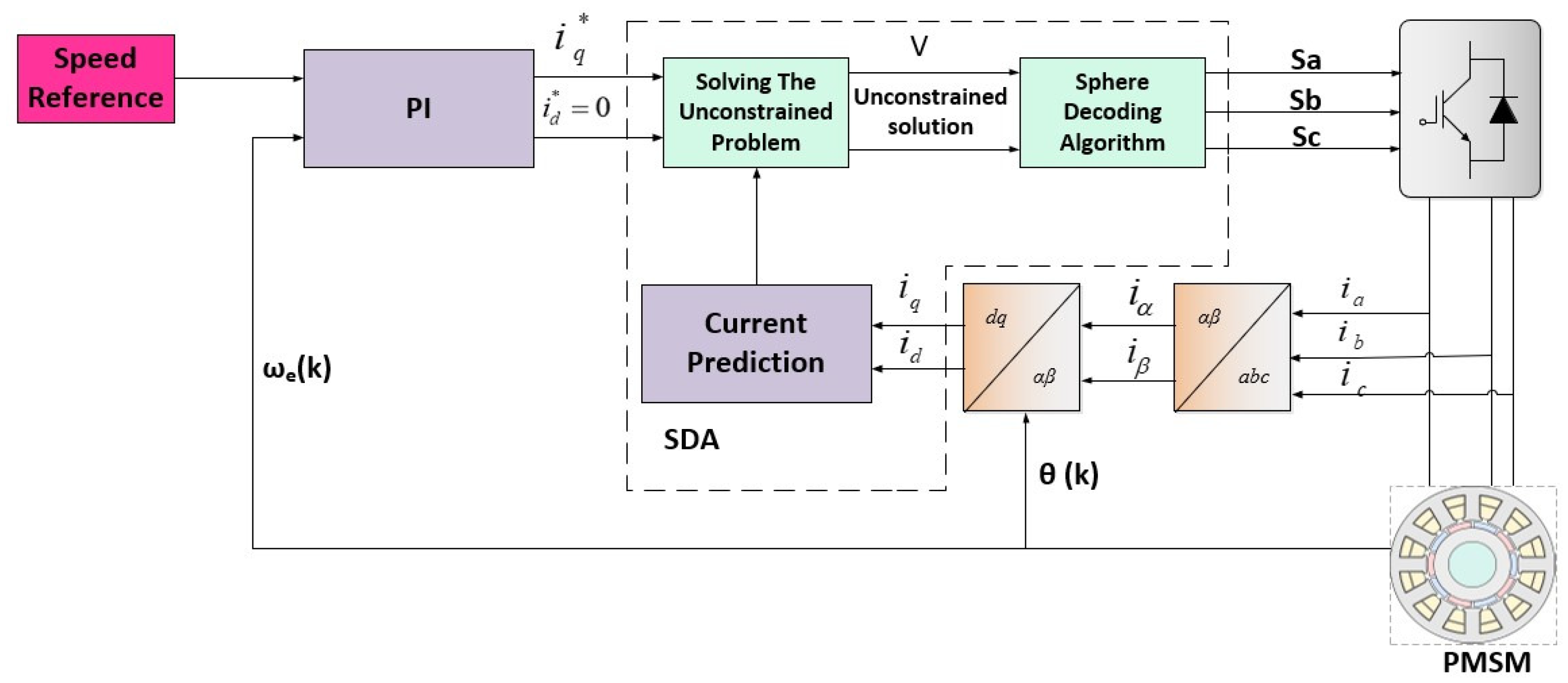

2.2. System Model and LPH-FCS-MPC Formulation

- and are the currents on the d- and q-axis, respectively;

- is the stator resistance;

- and are the d-axis and q-axis inductances;

- is the electrical angular speed of the rotor;

- is the permanent magnet flux linkage.

- Tracking Error: The squared norm of the difference between the reference current and the predicted current . The algorithm selects that minimizes this error.

- Control Effort: This includes a weighting factor that balances switching frequency and THD. A higher reduces switching frequency but can increase THD.

2.3. Performance Metrics

2.3.1. THD

2.3.2. Switching Frequency

2.3.3. Stability Analysis

3. Proposed ANN Method

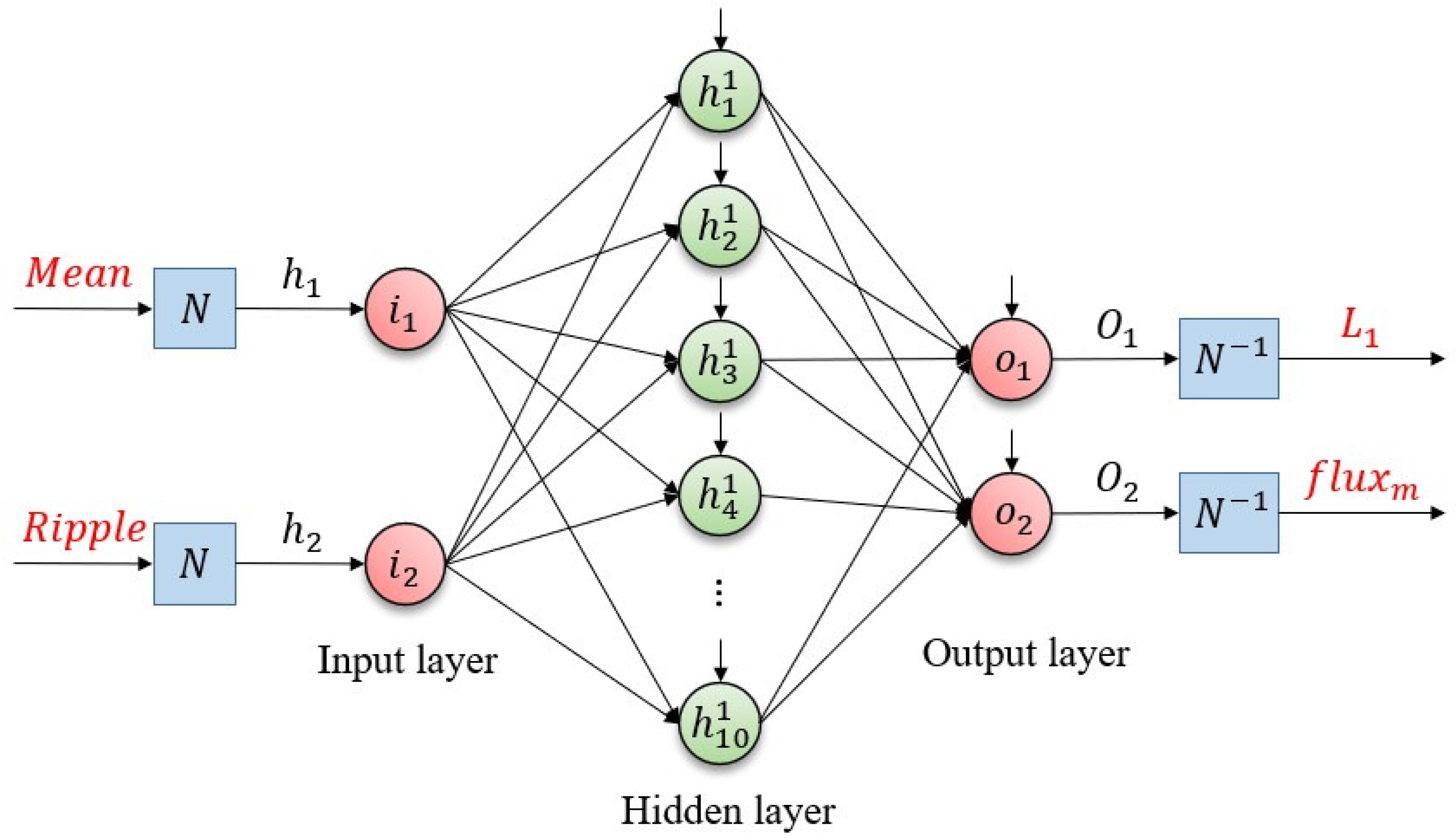

3.1. Artificial Neural Network Design for Parameter Mismatch Estimation

- Input layer: 2 neurons corresponding to the extracted features—mean () and ripple magnitude () of the current.

- Hidden layer: 10 neurons with sigmoid activation functions (tansig in MATLAB).

- Output layer: 2 neurons representing the estimated machine parameters—flux linkage () and inductance (), with linear activation functions (purelin in MATLAB).

3.2. Rationale for Feature Selection

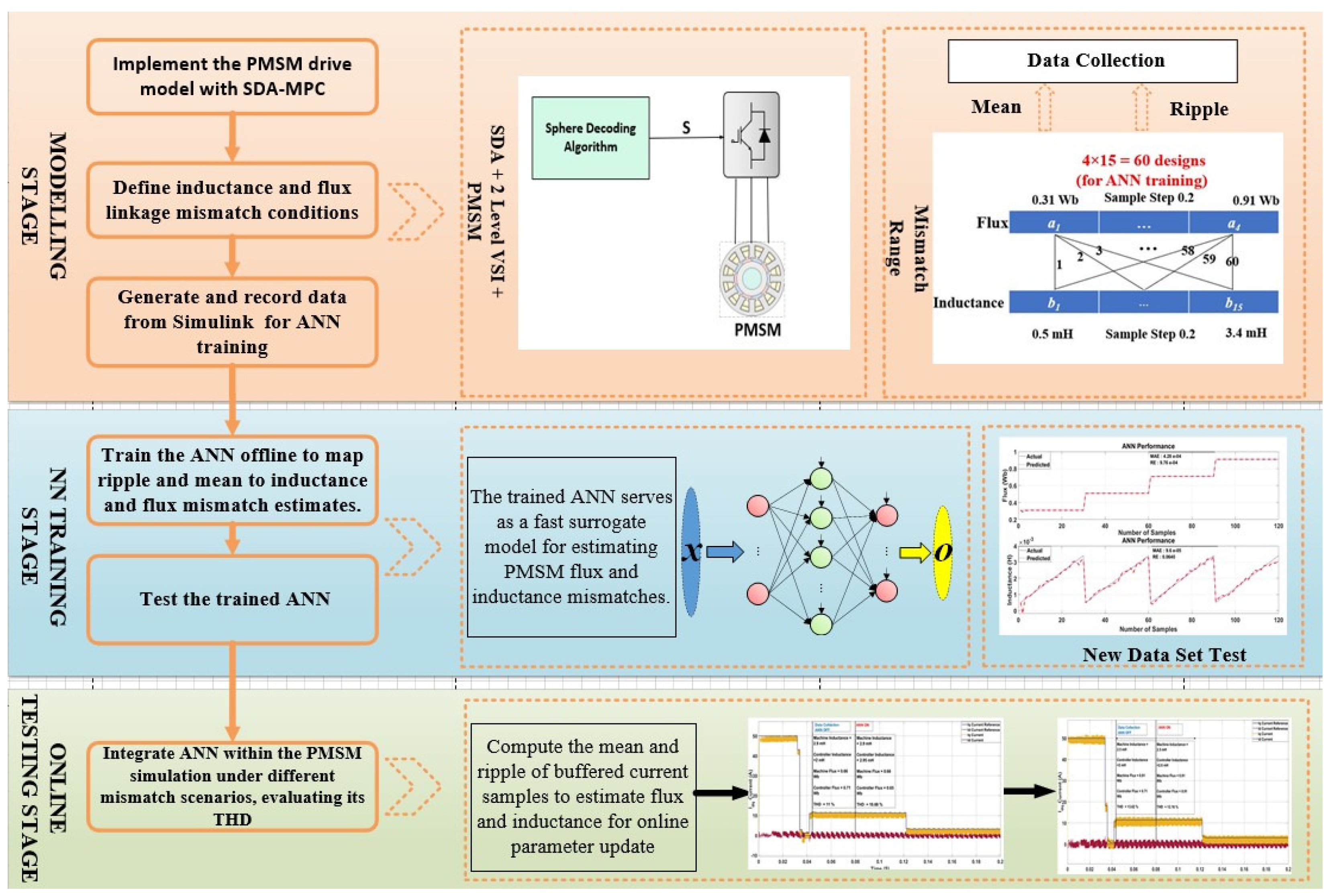

4. ANN Data Collection and Training Performance

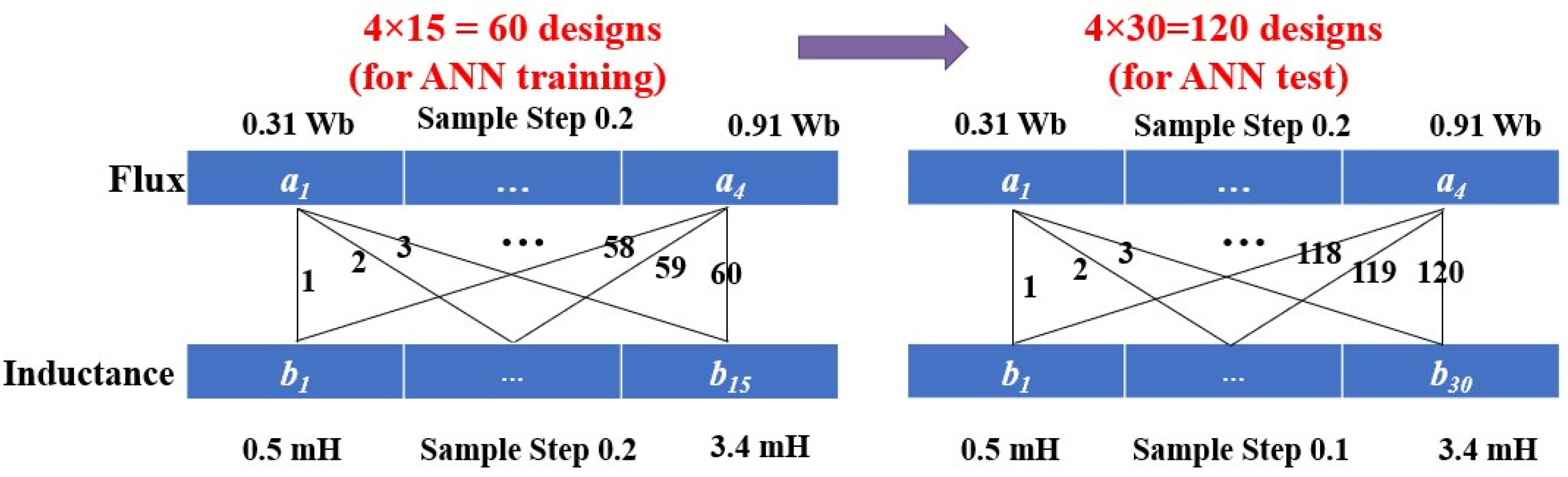

4.1. Data Generation for ANN Training

4.2. Training Procedure

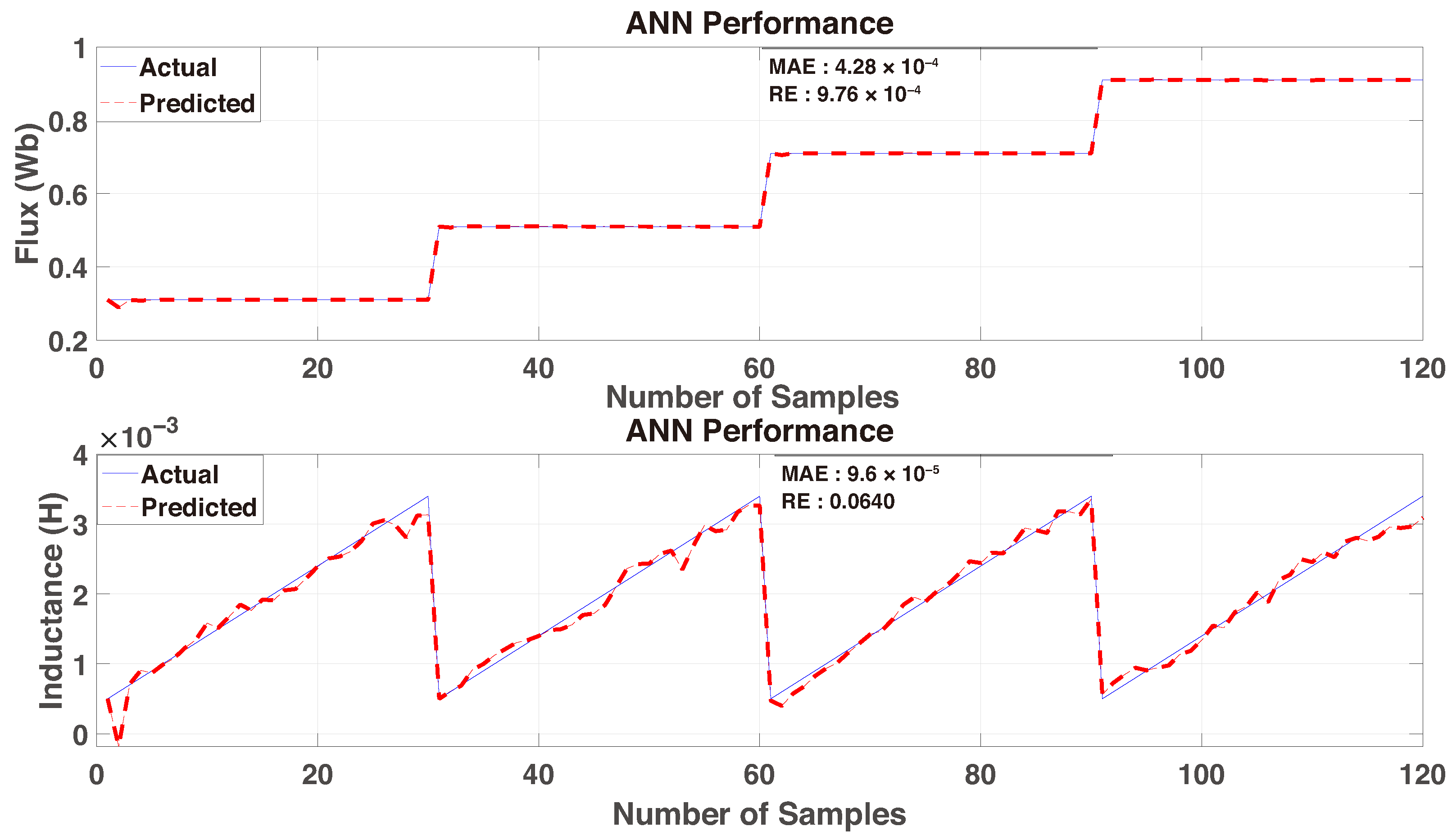

4.3. Performance Evaluation Metrics

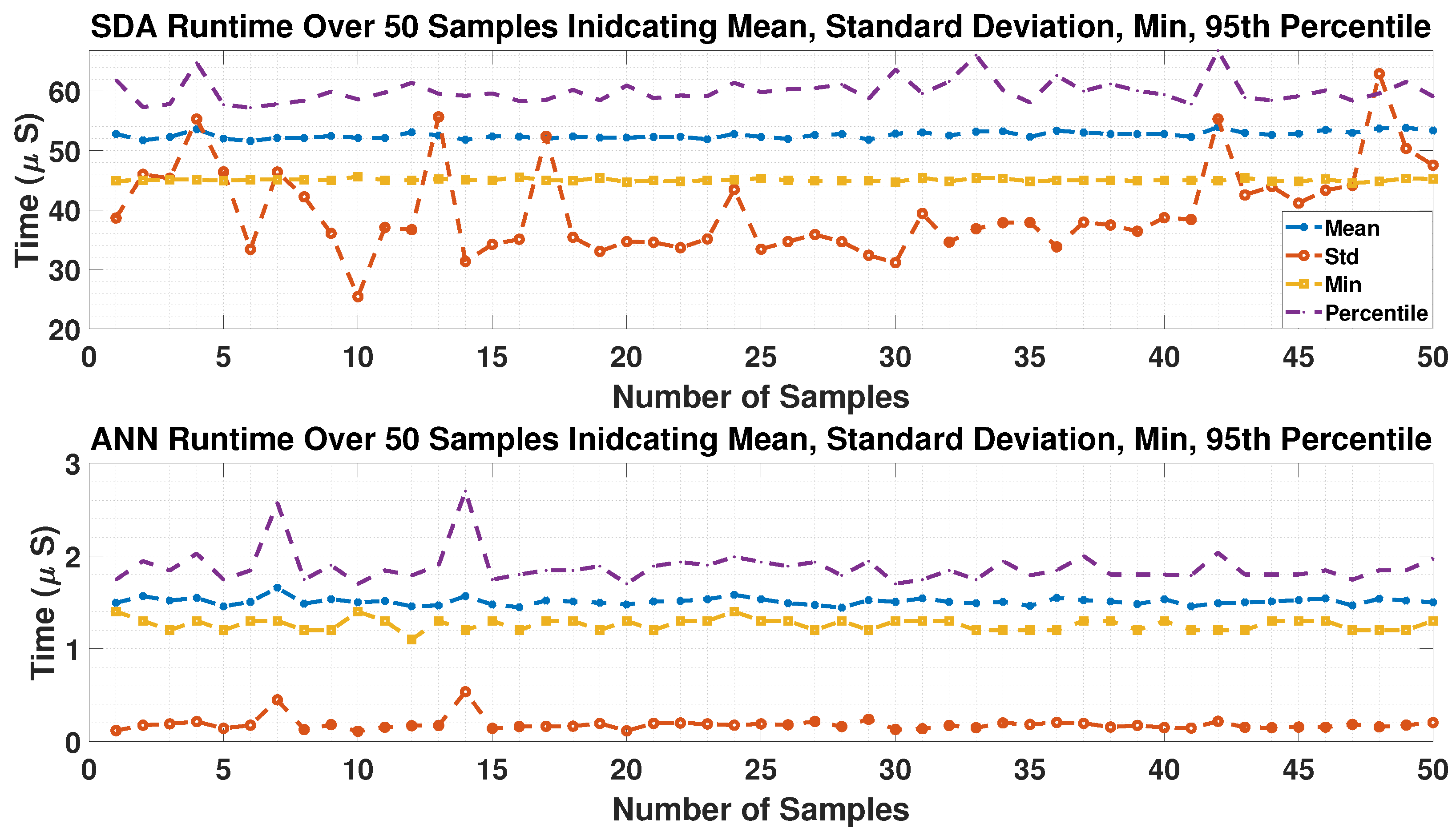

4.4. ANN Runtime

5. Results

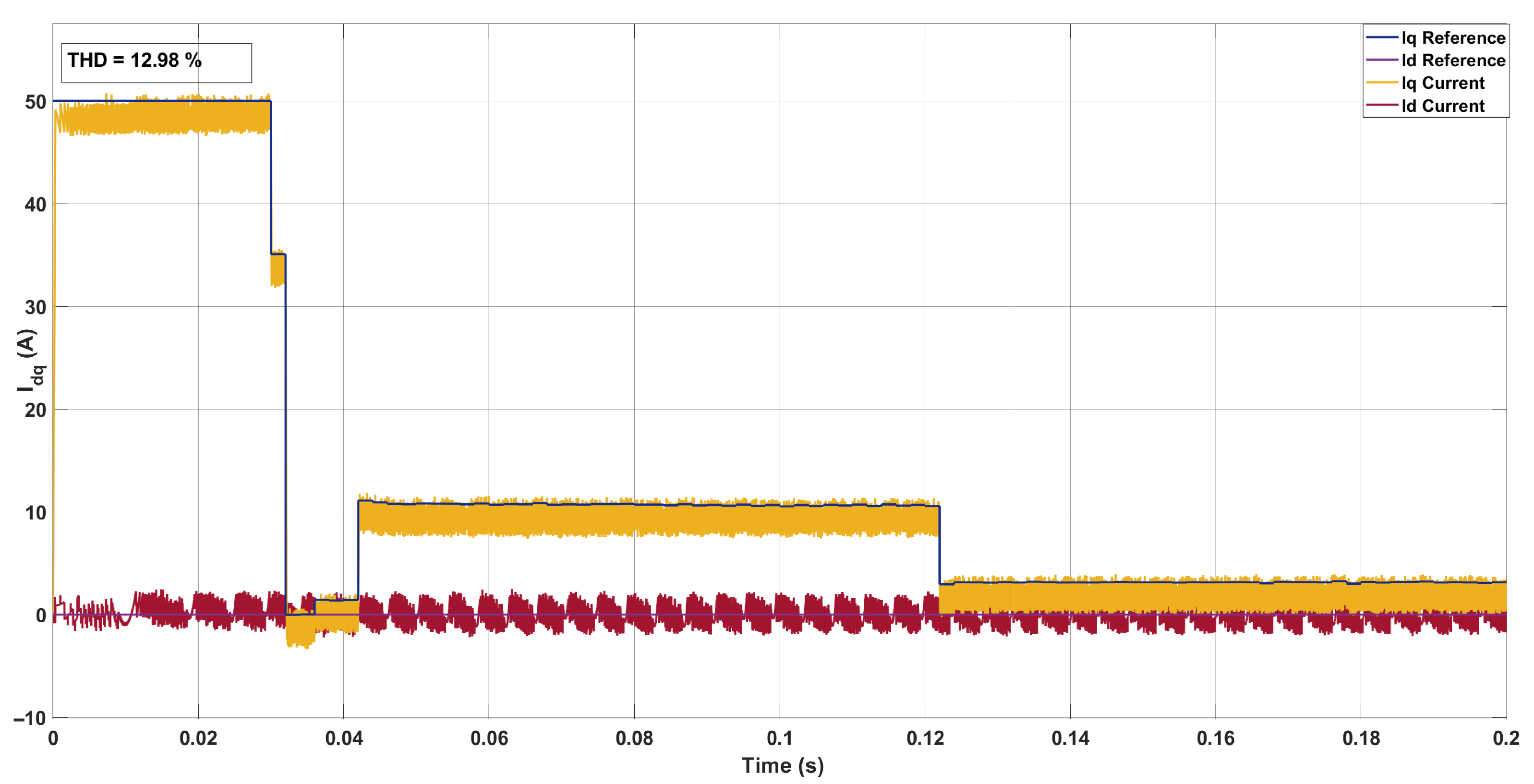

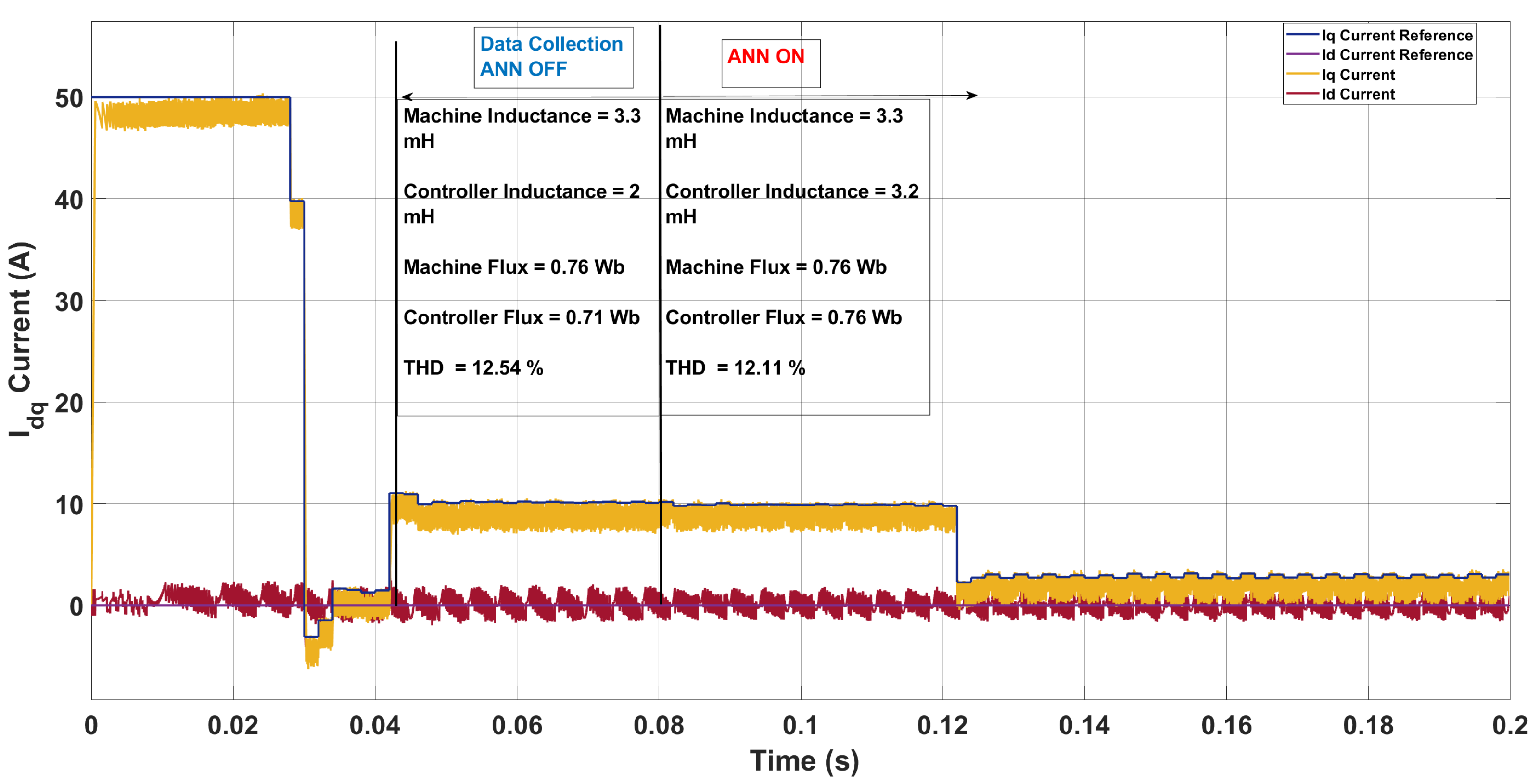

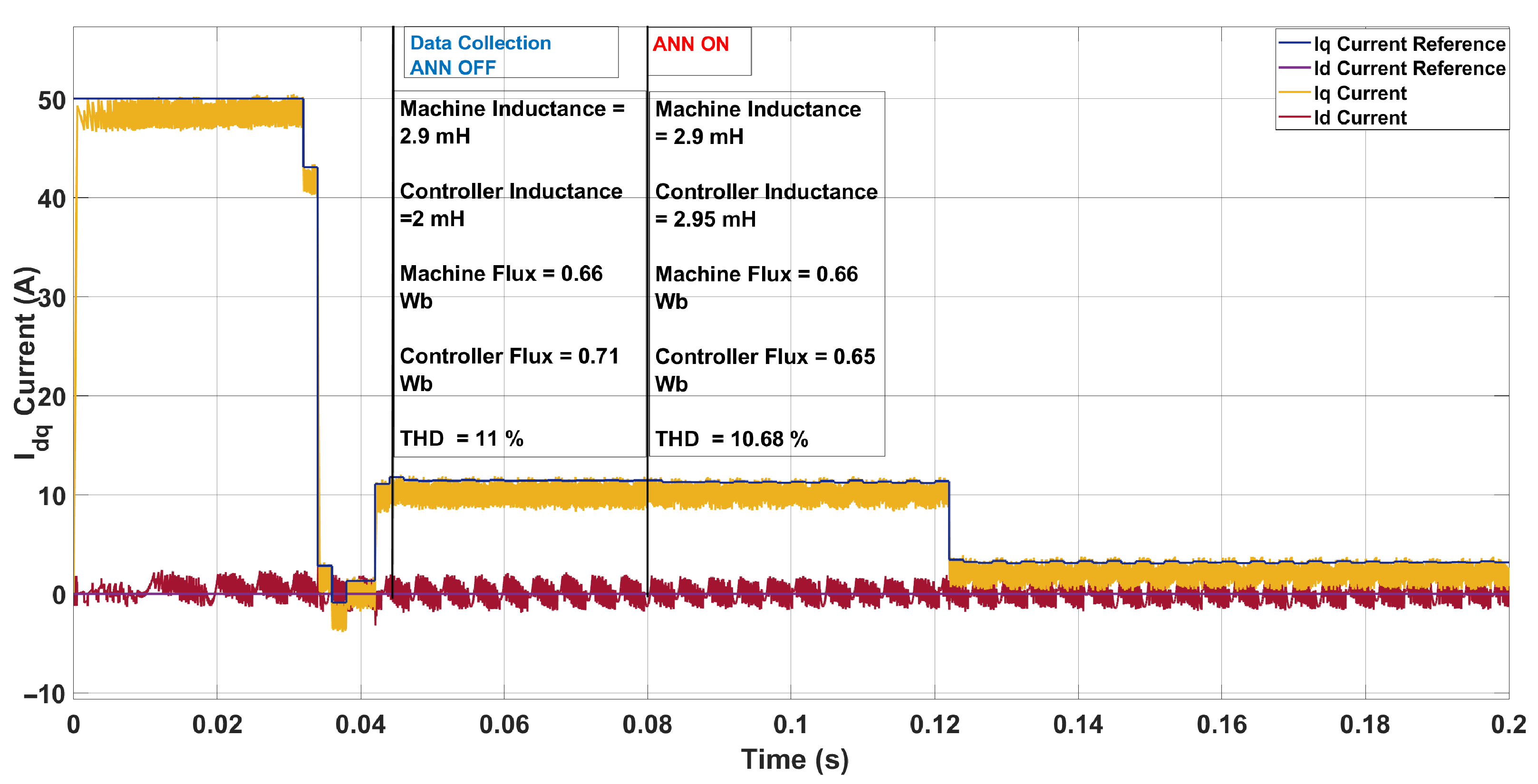

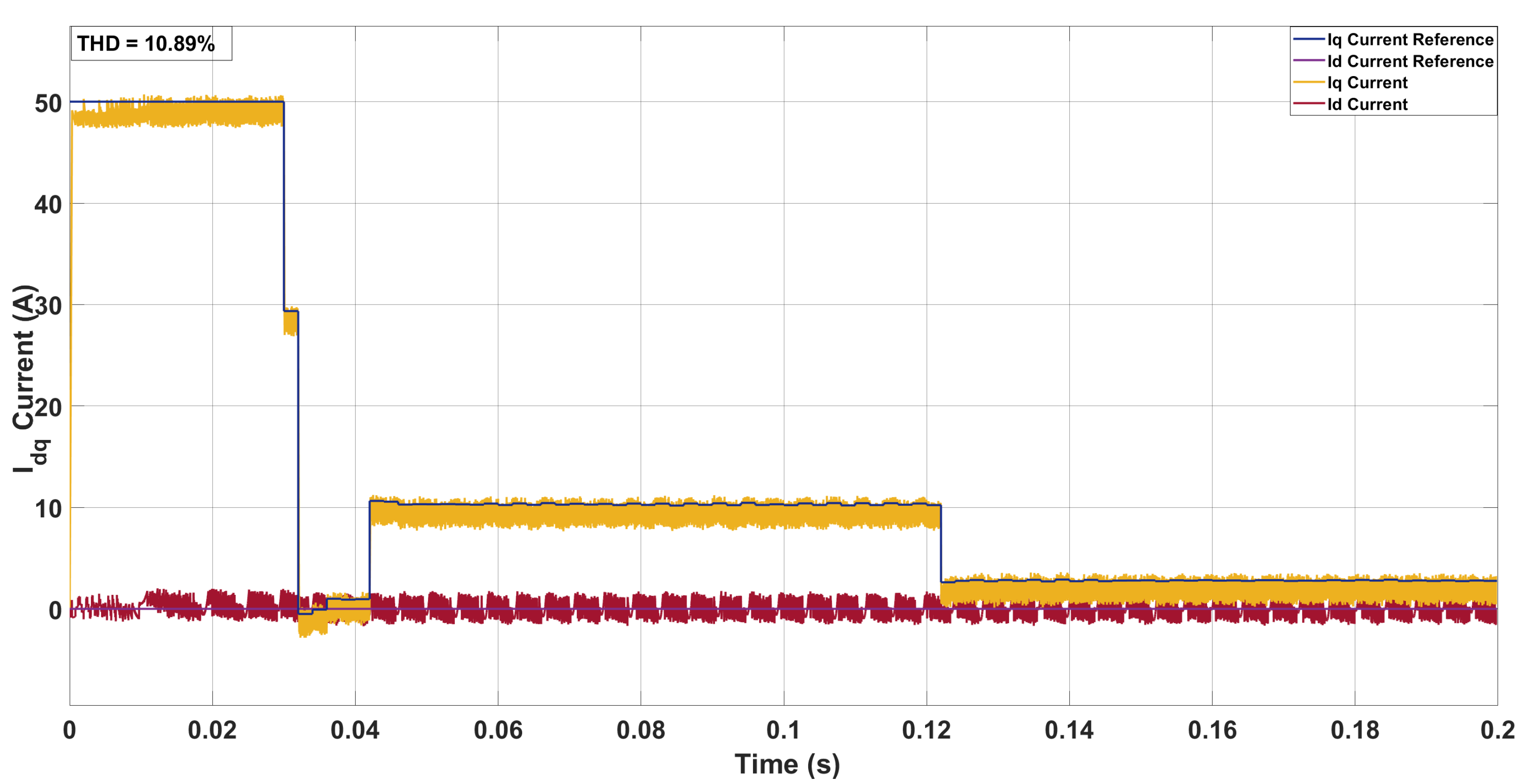

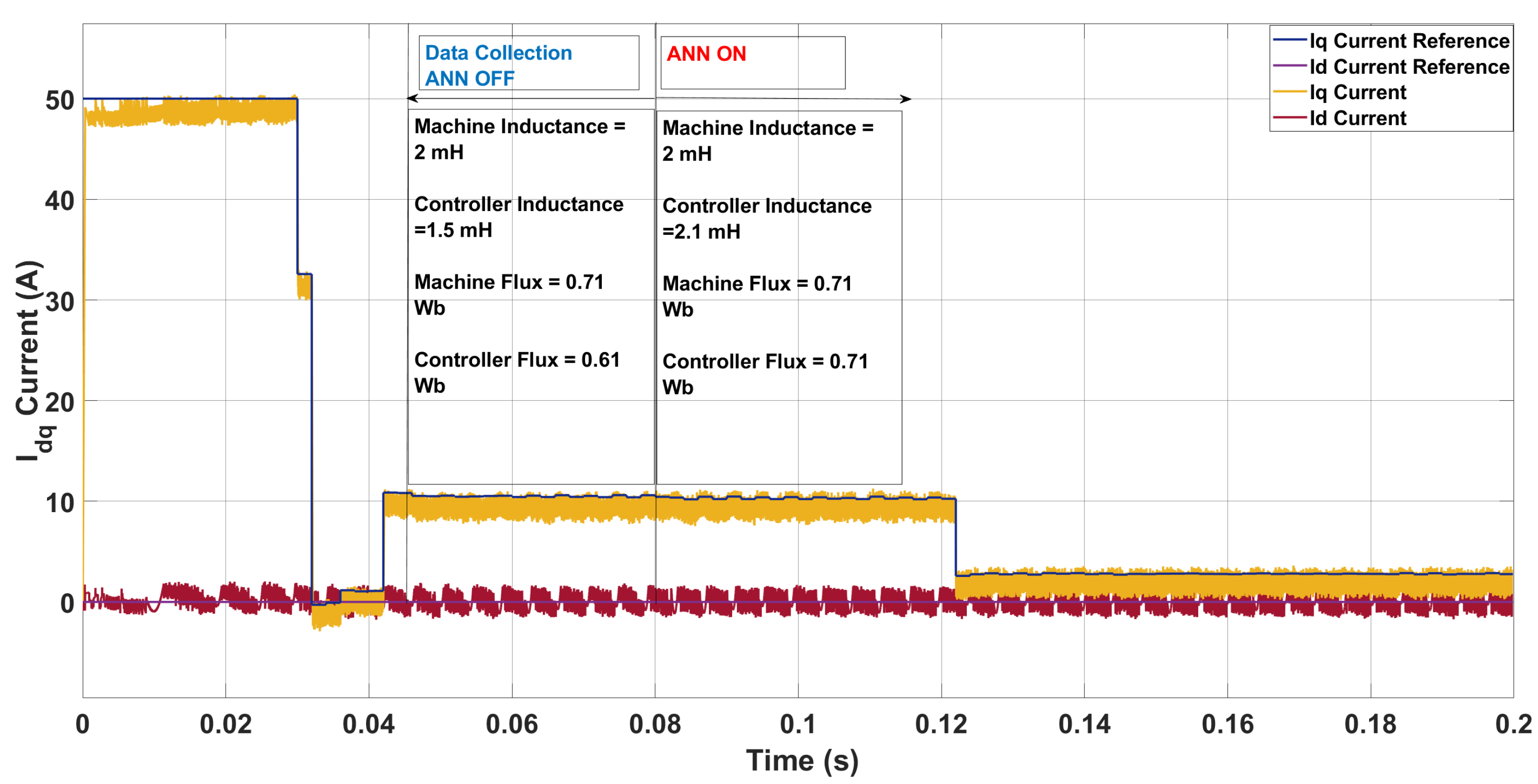

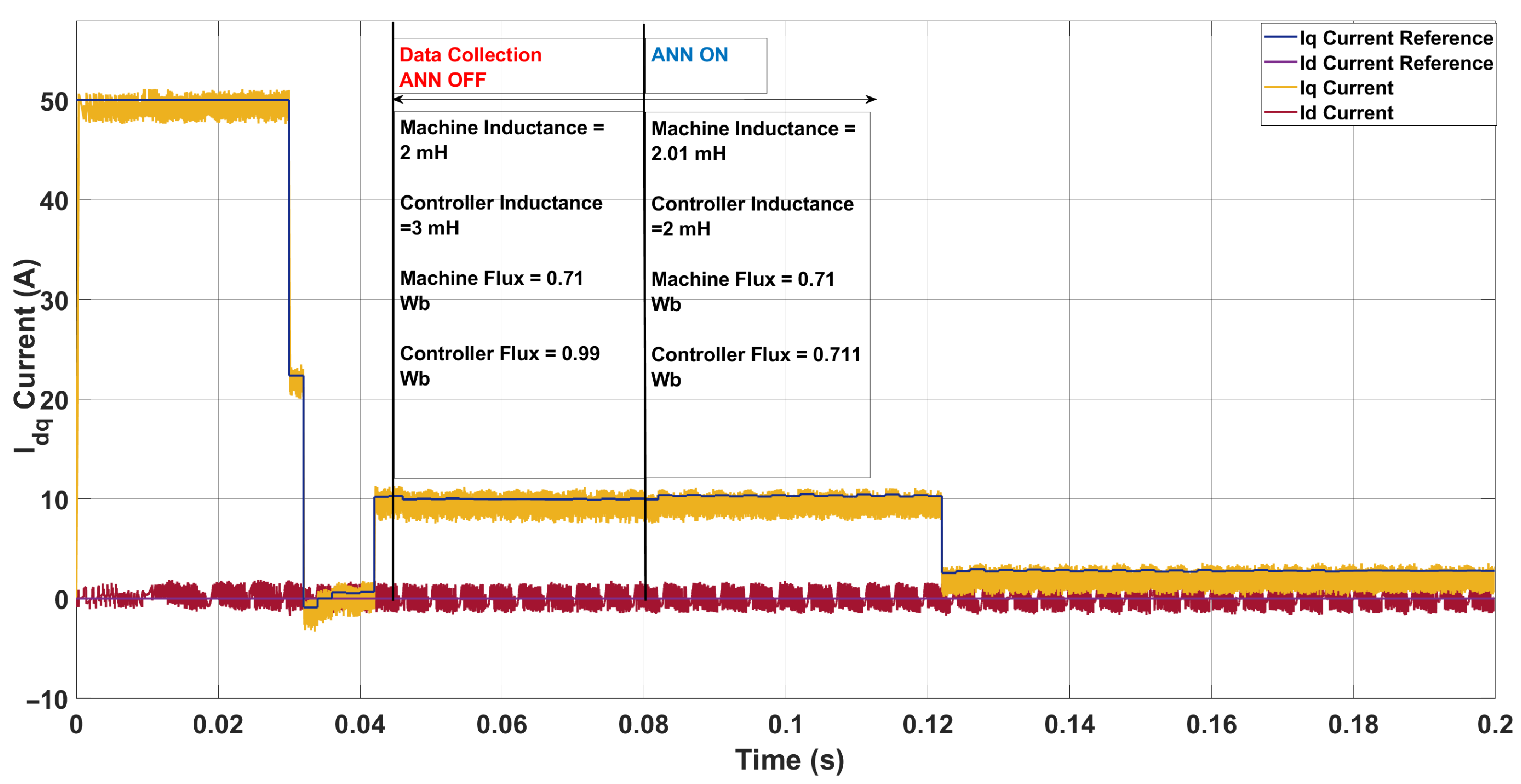

5.1. System Configuration 1

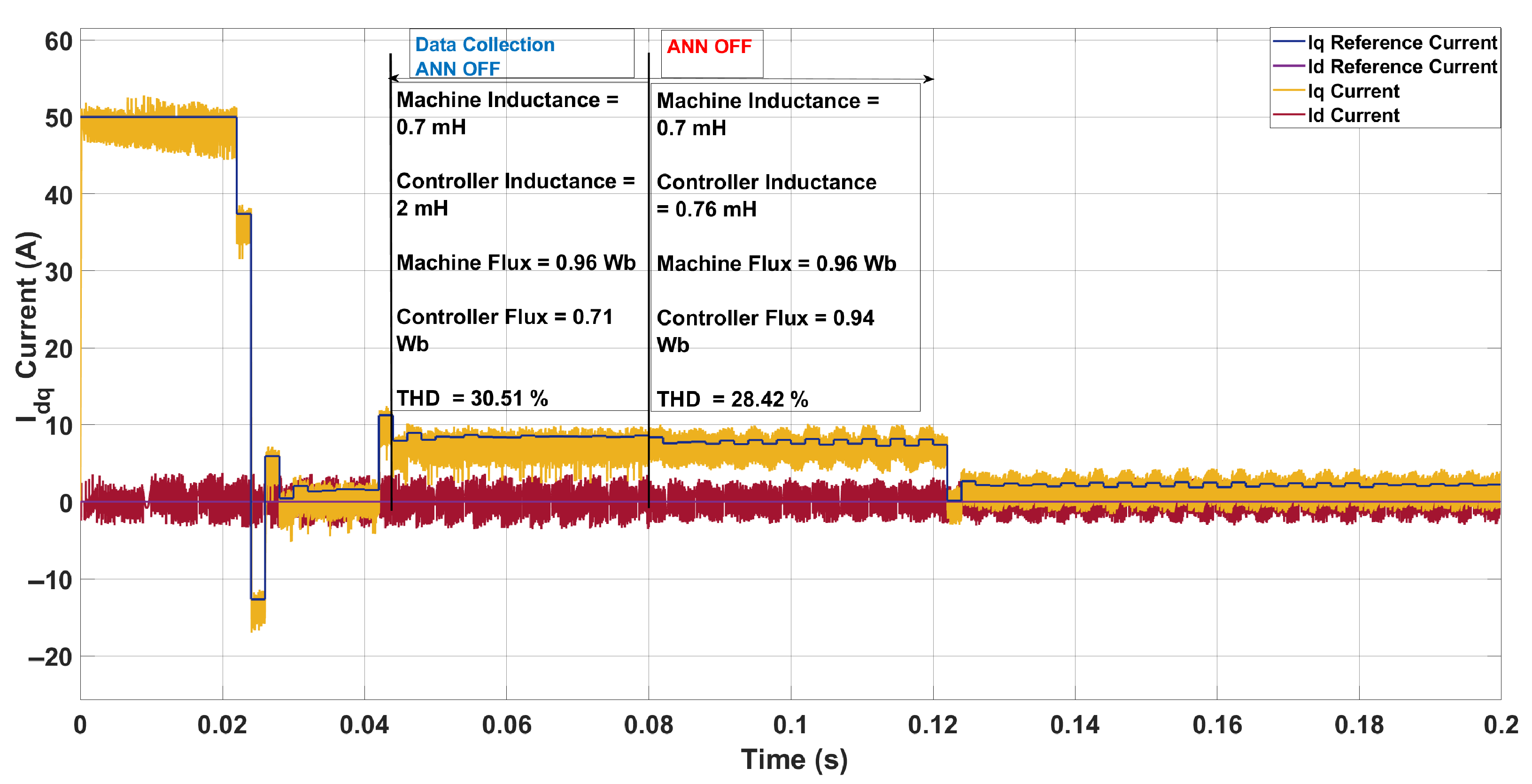

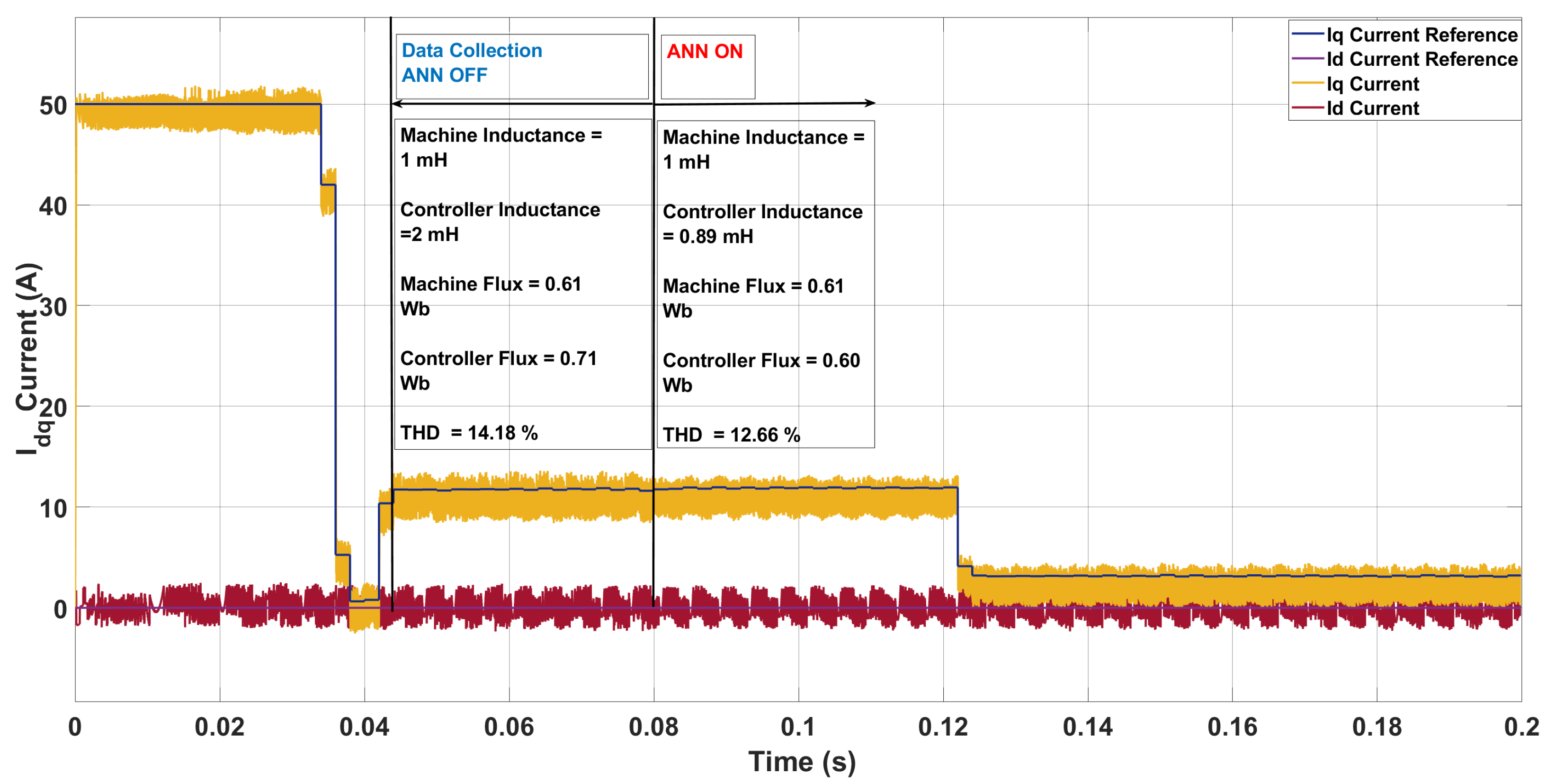

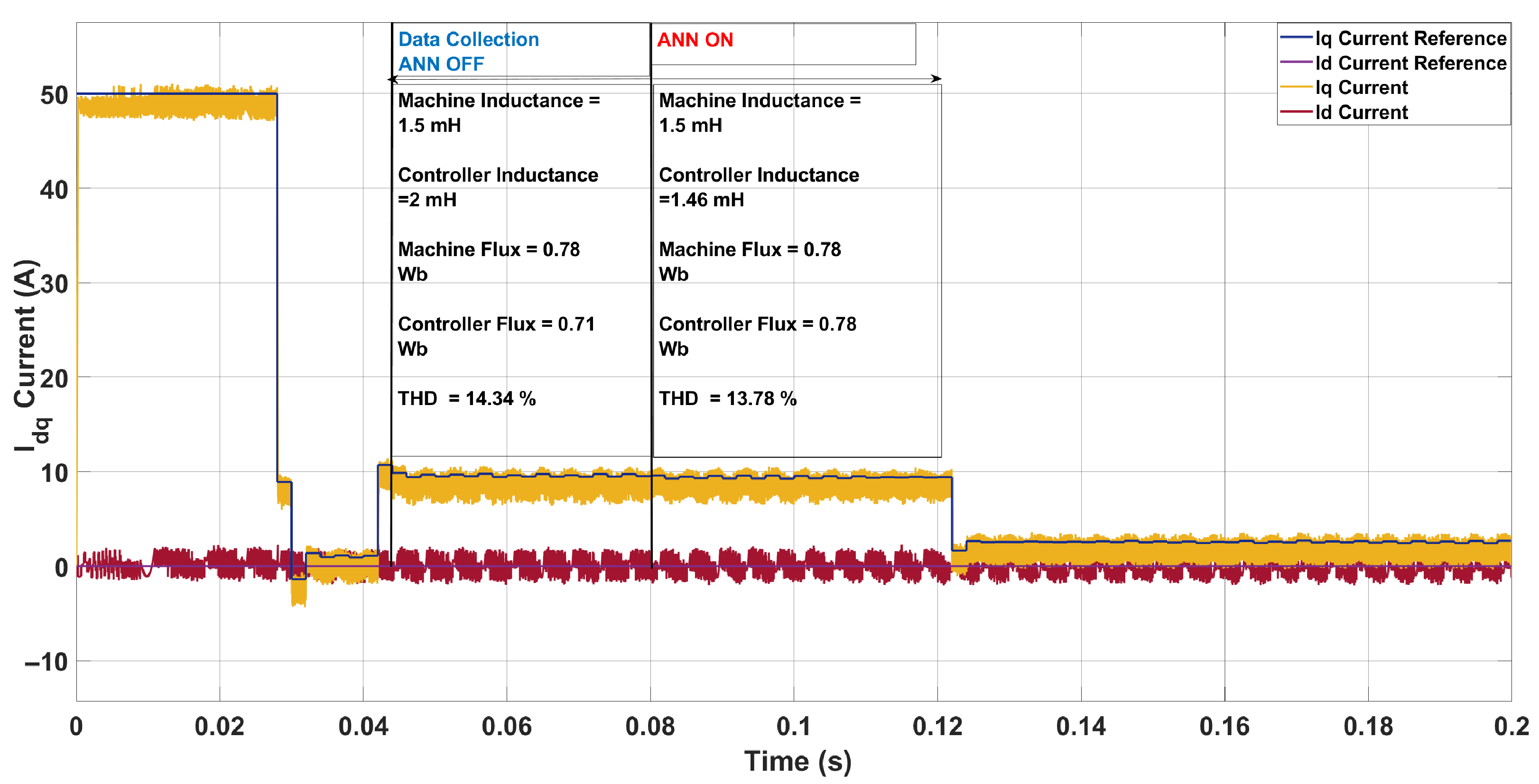

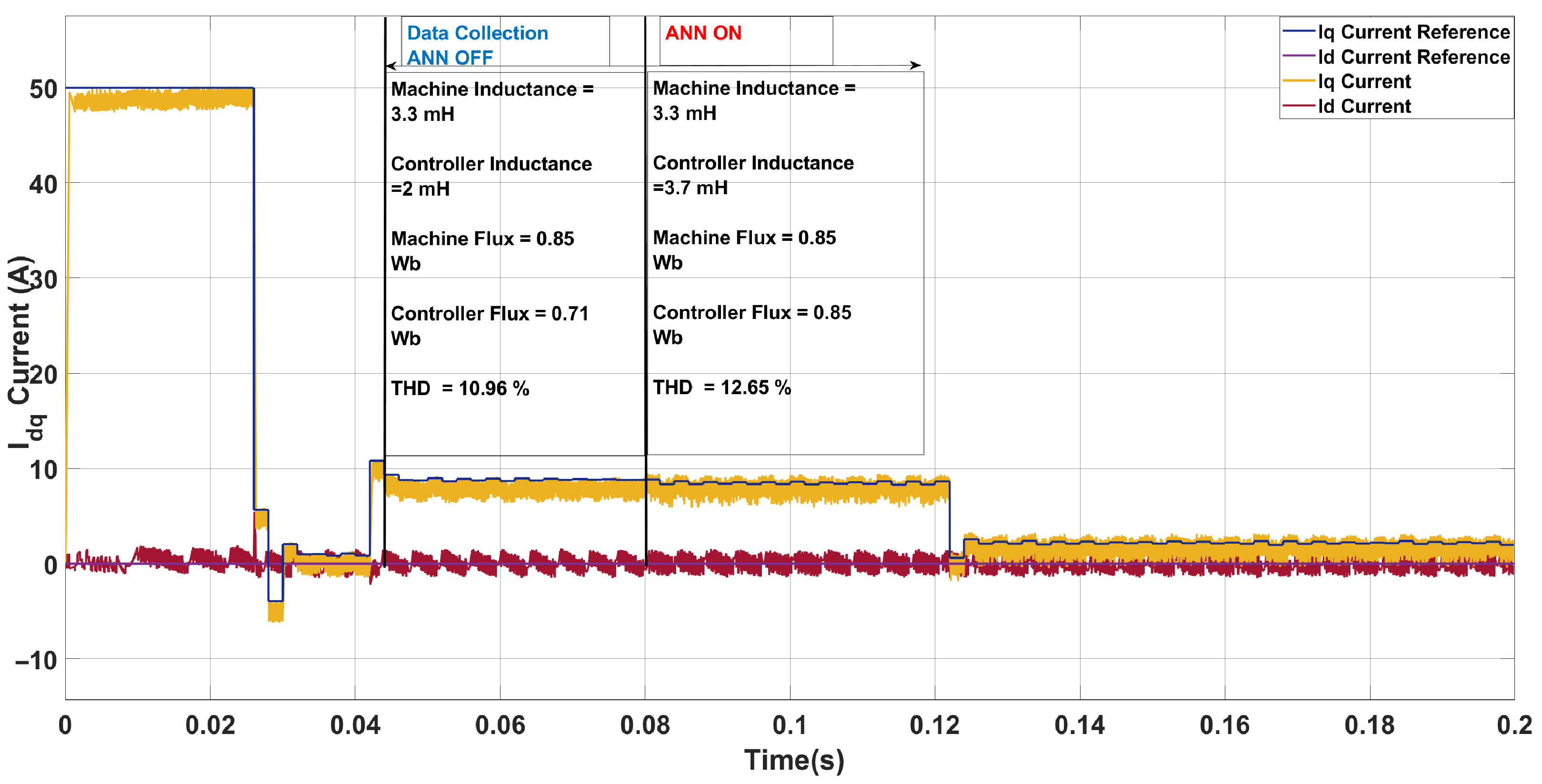

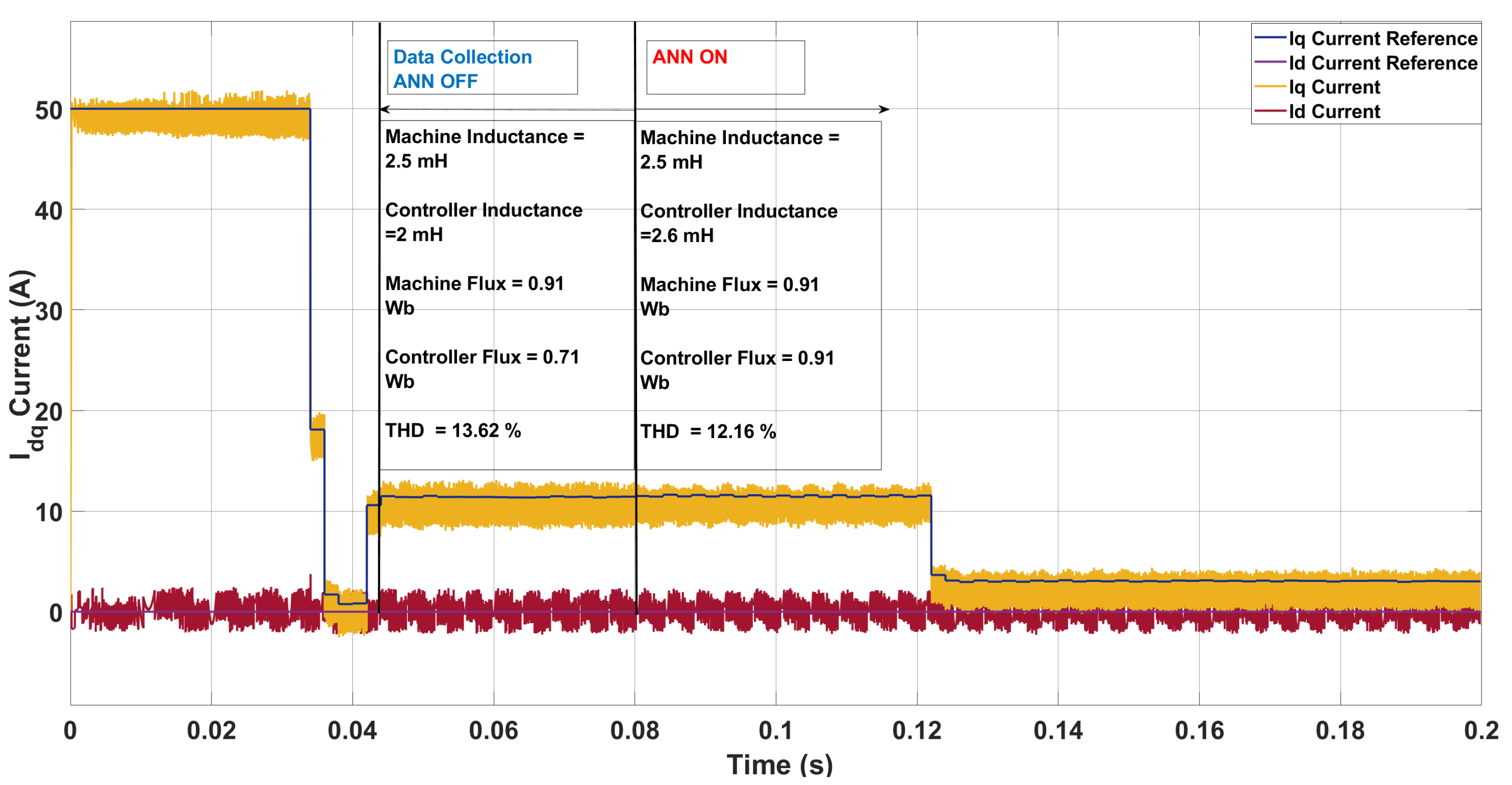

5.2. System Configuration 2

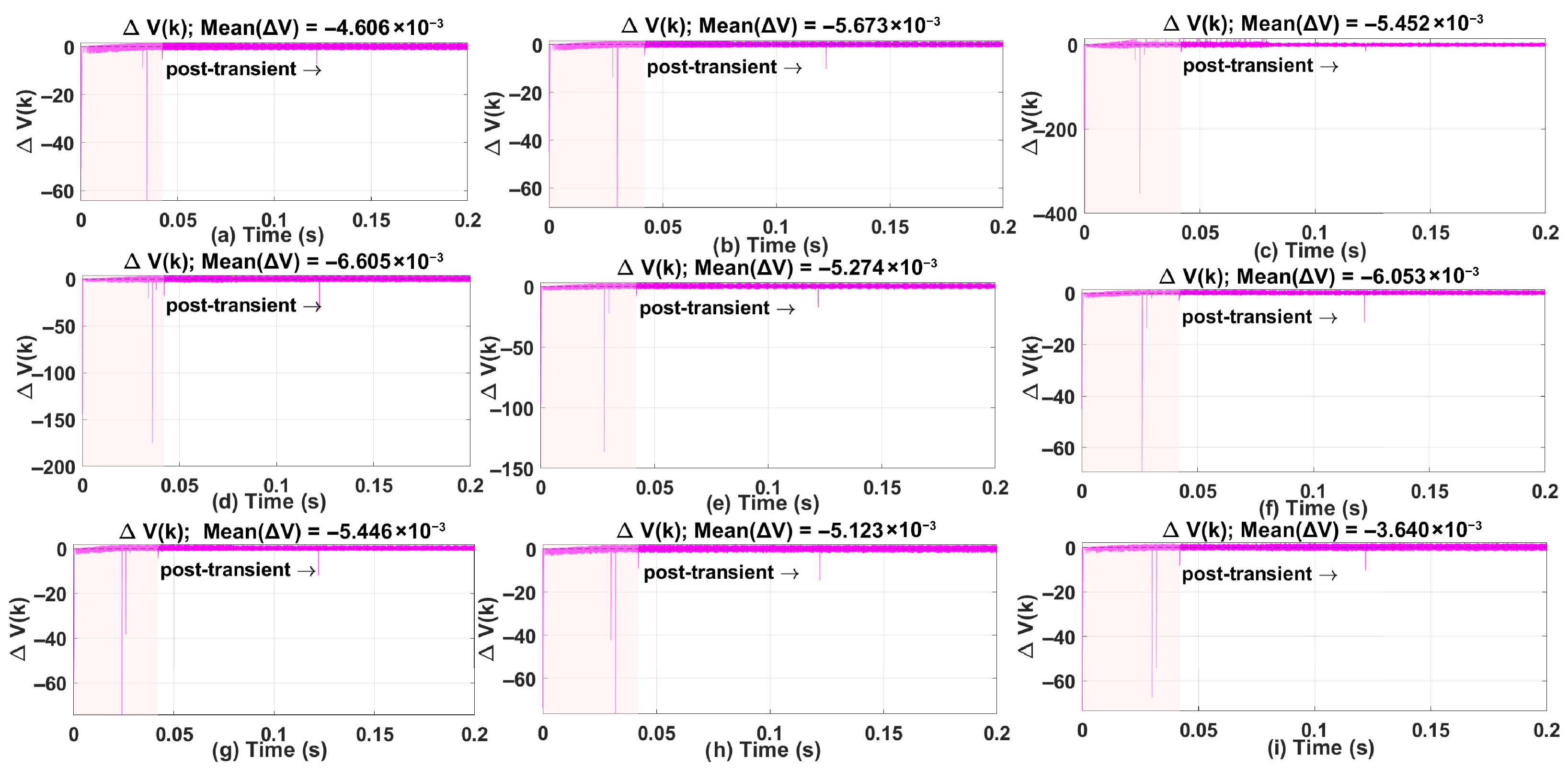

5.3. Lyapunov Stability Analysis

- Transient Region (0–0.042 s, shaded pink): This interval contains large spikes in caused by rapid changes in the tracking error during the initial response. These spikes occur because the controller is compensating for a reference change and the q-axis current dynamics dominate this phase, as seen in the current plots in Section 5.1 and Section 5.2. ANN adaptation also begins in this period, contributing to short bursts in .

- Post-Transient Region (after 0.042 s): Beyond the transient, remains close to zero with a slight negative bias, indicating that the Lyapunov function is bounded and exhibits a non-increasing trend. This region reflects steady-state behavior before and after ANN adaptation stabilizes. For stability assessment, the mean of is computed in this post-transient window, and the values reported in each subplot confirm practical stability.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yin, Z.; Deng, F.; Kaddah, S.S.; Ghanem, A.; Abulanwar, S.; Vazquez, S. Voltage-Noise-Tolerated Model-Free Predictive Control for LC-Filtered Voltage Source Inverters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 5048–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.J.; Lee, D.M. A New Bumpless Rotor-Flux Position Estimation Scheme for Vector-Controlled Washing Machine. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2016, 12, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodas, J.; Barrero, F.; Arahal, M.R.; Martín, C.; Gregor, R. Online Estimation of Rotor Variables in Predictive Current Controllers: A Case Study Using Five-Phase Induction Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 5348–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, S. Torque Ripple Suppression for Open-End Winding Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Machine Drives With Predictive Current Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 1771–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. From PID to Active Disturbance Rejection Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Liu, L.; Vazquez, S.; Xu, R.; Dong, Z.; Liu, J.; Leon, J.I.; Wu, L.; Franquelo, L.G. Disturbance and Uncertainty Attenuation for Speed Regulation of PMSM Servo System Using Adaptive Optimal Control Strategy. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 3410–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Lang, X.; Long, J.; Xu, D. Flux Immunity Robust Predictive Current Control With Incremental Model and Extended State Observer for PMSM Drive. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 9267–9279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragičević, T.; Vazquez, S.; Wheeler, P. Advanced Control Methods for Power Converters in DG Systems and Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 5847–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yang, M.; Dianguo, X. An Adaptive Robust Predictive Current Control for PMSM with Online Inductance Identification. Int. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2012, 7, 3845–3856. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Peretti, L.; Wu, L. Model-Free Current Predictive Control for PMSMs With Ultralocal Model Employing Fixed-Time Observer and Extremum-Seeking Method. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 10682–10693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, L. A Simple Motor-Parameter-Free Model Predictive Voltage Control for PMSM Drives Based on Incremental Model. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2024, 12, 2845–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liang, X.; Guo, H.; Zhuang, X. Robust Model Predictive Current Control of PMSM Based on Nonlinear Extended State Observer. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdale, S.; Jagdale, S. Neural Network Application in Core Power Electronics and Motor Drives—Power Electronics News. 2022. Available online: https://www.powerelectronicsnews.com/neural-network-application-in-core-power-electronics-and-motor-drives/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Skansi, S. Introduction to Deep Learning: From Logical Calculus to Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, K.; Stinchcombe, M.; White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 1989, 2, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.S.; Rovetta, S.; Do, T.D.; Dragicević, T.; Diab, A.A.Z. A Neural-Network-Based Model Predictive Control of Three-Phase Inverter With an Output LC Filter. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 124737–124749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, S.; Marino, D.; Zafra, E.; Peña, M.D.V.; Rodríguez-Andina, J.J.; Franquelo, L.G.; Manic, M. An Artificial Intelligence Approach for Real-Time Tuning of Weighting Factors in FCS-MPC for Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 11987–11998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra, E.; Granado, J.; Lecuyer, V.B.; Vazquez, S.; Alcaide, A.M.; Leon, J.I.; Franquelo, L.G. Computationally Efficient Sphere Decoding Algorithm Based on Artificial Neural Networks for Long-Horizon FCS-MPC. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Hussaini, H.; Yang, T.; Dragičević, T.; Bozhko, S.; Wheeler, P.; Vazquez, S. Inverse Application of Artificial Intelligence for the Control of Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 1535–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Tran Ngoc, H.; Nguyen Hoang, T.; Jeon, J. Recurrent Neural Network-Based Robust Adaptive Model Predictive Speed Control for PMSM With Parameter Mismatch. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 70, 6219–6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Gupta, R.A.; Bansal, A.K. Identification and Control of PMSM Using Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics, Vigo, Spain, 4–7 June 2007; pp. 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeer, A.; Mohamed, I.S.; Malidarreh, P.B.; Hattabi, I.; Liu, L. An Artificial Neural Network-Based Model Predictive Control for Three-Phase Flying Capacitor Multilevel Inverter. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 70305–70316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwumi, J.O.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Vazquez, S.; Ruiz, H.S. Comparative Study of Sphere Decoding Algorithm and FCS-MPC for PMSMs in Aircraft Application. Aerospace 2025, 12, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Tian, W.; Karamanakos, P.; Kennel, R. A Dual Reference Frame Multistep Direct Model Predictive Current Control with a Disturbance Observer for SPMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 2857–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortombina, L.; Karamanakos, P.; Zigliotto, M. Robustness Analysis of Long-Horizon Direct Model Predictive Control: Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 21st Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics (COMPEL), Aalborg, Denmark, 9–12 November 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Young, H.; Wang, F.; Rodríguez, J. Generalized Data-Driven Model-Free Predictive Control for Electrical Drive Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 7642–7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, B.; Jiang, B.; Han, J.; Wen, C.Y. Disturbance Observer-Based Model Predictive Control for an Unmanned Underwater Vehicle. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, J.; Huang, L. Model-Free Predictive Current Control of PMSM Drives Based on Extended State Observer Using Ultralocal Model. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Lei, T. Constrained Model Free Adaptive Predictive Perimeter Control and Route Guidance for Multi-Region Urban Traffic Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, F.; Young, H.; Ke, D.; Rodríguez, J. Autoregressive Moving Average Model-Free Predictive Current Control for PMSM Drives. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 3874–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Tang, R.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wu, G.; Huang, S. Robust predictive current control of permanent magnet synchronous motor using voltage coefficient matrix update. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 159, 109999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahraoui, Y.; Zaihidee, F.M.; Kermadi, M.; Mekhilef, S.; Alhamrouni, I.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Stojcevski, A. Optimal Tuning of Fractional Order Sliding Mode Controller for PMSM Speed Using Neural Network with Reinforcement Learning. Energies 2023, 16, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Kawaguchi, T.; Hashimoto, S. A Discrete Space Vector Modulation MPC-Based Artificial Neural Network Controller for PMSM Drives. Machines 2025, 13, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Mao, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, L.; Wang, Z. A Model-Based and Data-Driven Integrated Temperature Estimation Method for PMSM. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 8553–8561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, K.; Dybkowski, M. Experimental Analysis of the Current Sensor Fault Detection Mechanism Based on Neural Networks in the PMSM Drive System. Electronics 2023, 12, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, K.A.; Beig, A.R.; Al Jaafari, K.A.; Aung, Z. ANN-Based Improved Direct Torque Control of Open-End Winding Induction Motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 12030–12040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svozil, D.; Kvasnicka, V.; Pospichal, J. Introduction to multi-layer feed-forward neural networks. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1997, 39, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragičević, T.; Wheeler, P.; Blaabjerg, F. Artificial Intelligence Aided Automated Design for Reliability of Power Electronic Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 7161–7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Dragicevic, T.; Xie, L.; Blaabjerg, F. Artificial Intelligence-Based Control Design for Reliable Virtual Synchronous Generators. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 9453–9464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, T.; Wang, X.; Bozhko, S.; Wheeler, P. Machine Learning Based Correction Model in PMSM Power Loss Estimation for More-Electric Aircraft Applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 23rd International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Hamamatsu, Japan, 24–27 November 2020; pp. 1940–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.B.; Chen, Y.Q.; Babri, H. Classification ability of single hidden layer feedforward neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2000, 11, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, T.; Quevedo, D.E. Performance of Multistep Finite Control Set Model Predictive Control for Power Electronics. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanakos, P.; Geyer, T. Guidelines for the Design of Finite Control Set Model Predictive Controllers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 7434–7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| State Variables | |

| Input | |

| Output | |

| State Matrices | , , , |

| Module | Mean | Std | Min | 95th-Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDA-MPC | 52.59 | 39.78 | 45.03 | 59.96 |

| ANN Estimator | 1.5 | 0.18 | 1.26 | 1.87 |

| Scenario | Param. | Controller | Machine | ANN Pred. | Pred. Mis. (%) | THD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L [mH] | 2.00 | 3.30 | 3.20 | 3.03 | 12.54 → 12.11 |

| [Wb] | 0.71 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.00 | ||

| 2 | L [mH] | 2.00 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 8.57 | 30.51 → 28.42 |

| [Wb] | 0.71 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 2.08 | ||

| 3 | L [mH] | 2.00 | 2.90 | 2.95 | 1.72 | 11.00 → 10.68 |

| [Wb] | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 1.52 |

| Scenario | Param. | Controller | Machine | ANN Pred. | Pred. Mis. (%) | THD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L [mH] | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 6.00 | 14.12 → 12.94 |

| [Wb] | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 1.64 | ||

| 2 | L [mH] | 2.00 | 3.30 | 3.70 | 12.12 | 10.96 → 12.65 |

| [Wb] | 0.71 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.00 | ||

| 3 | L [mH] | 2.00 | 1.50 | 1.46 | 2.67 | 14.34 → 13.78 |

| [Wb] | 0.71 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.00 | ||

| 4 | L [mH] | 2.00 | 2.50 | 2.60 | 4.00 | 13.62 → 12.16 |

| [Wb] | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Akinwumi, J.O.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Vazquez, S.; Ruiz, H.S. ANN-Based Online Parameter Correction for PMSM Control Using Sphere Decoding Algorithm. Sensors 2026, 26, 553. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020553

Akinwumi JO, Gao Y, Yuan X, Vazquez S, Ruiz HS. ANN-Based Online Parameter Correction for PMSM Control Using Sphere Decoding Algorithm. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):553. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020553

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkinwumi, Joseph O., Yuan Gao, Xin Yuan, Sergio Vazquez, and Harold S. Ruiz. 2026. "ANN-Based Online Parameter Correction for PMSM Control Using Sphere Decoding Algorithm" Sensors 26, no. 2: 553. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020553

APA StyleAkinwumi, J. O., Gao, Y., Yuan, X., Vazquez, S., & Ruiz, H. S. (2026). ANN-Based Online Parameter Correction for PMSM Control Using Sphere Decoding Algorithm. Sensors, 26(2), 553. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020553