Prediction and Performance of BDS Satellite Clock Bias Based on CNN-LSTM-Attention Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Sources

3. Model and Methodology

3.1. CNN Principle

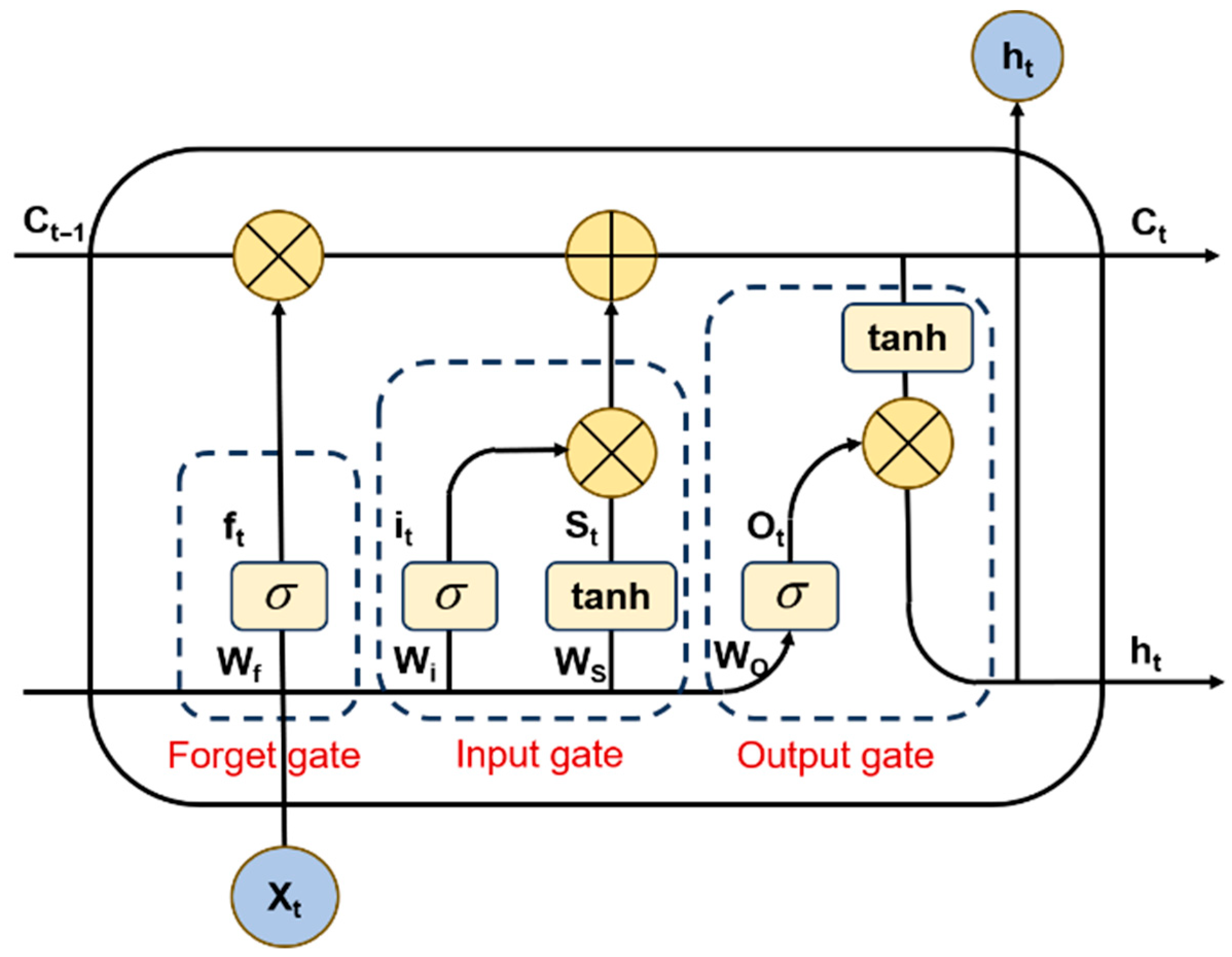

3.2. LSTM Principle

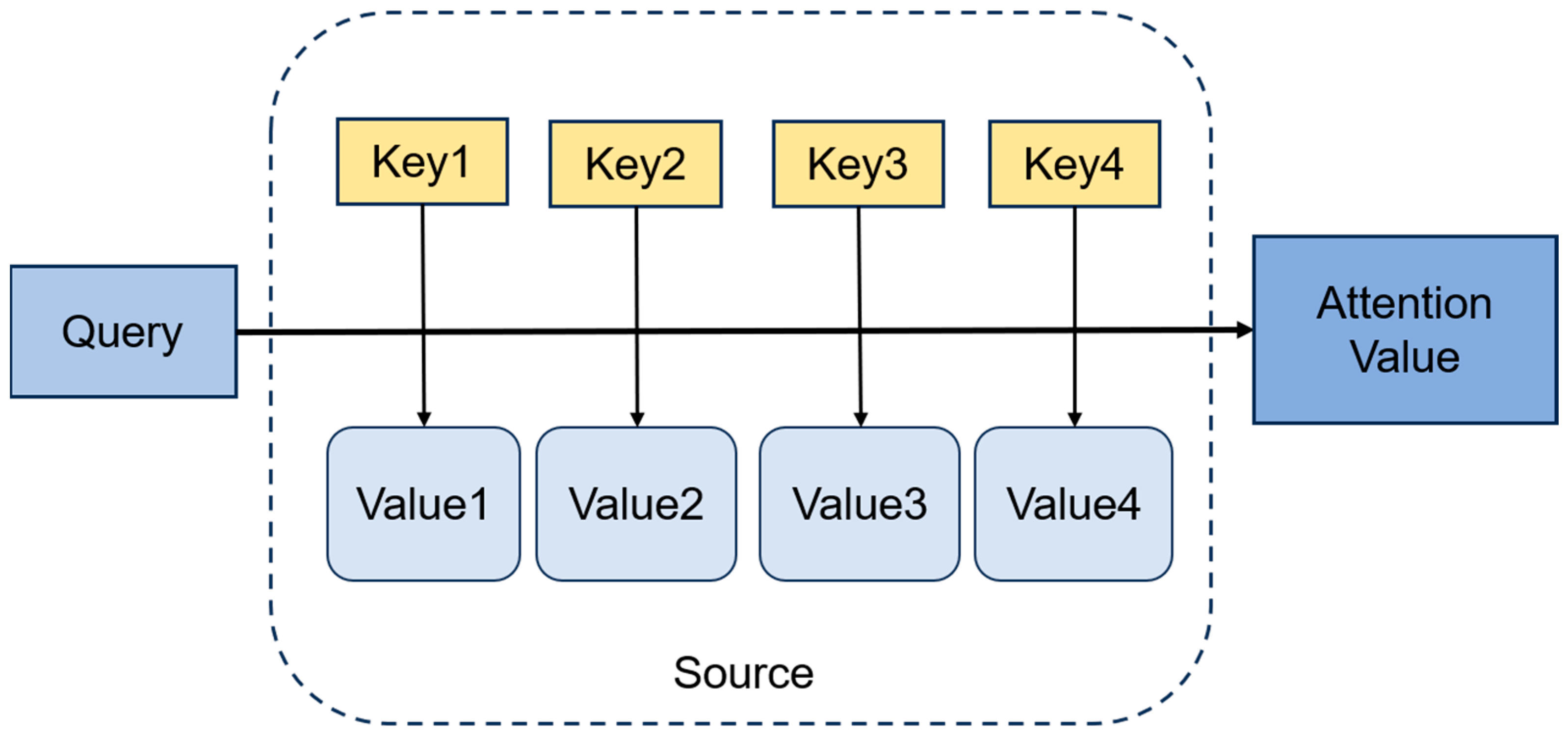

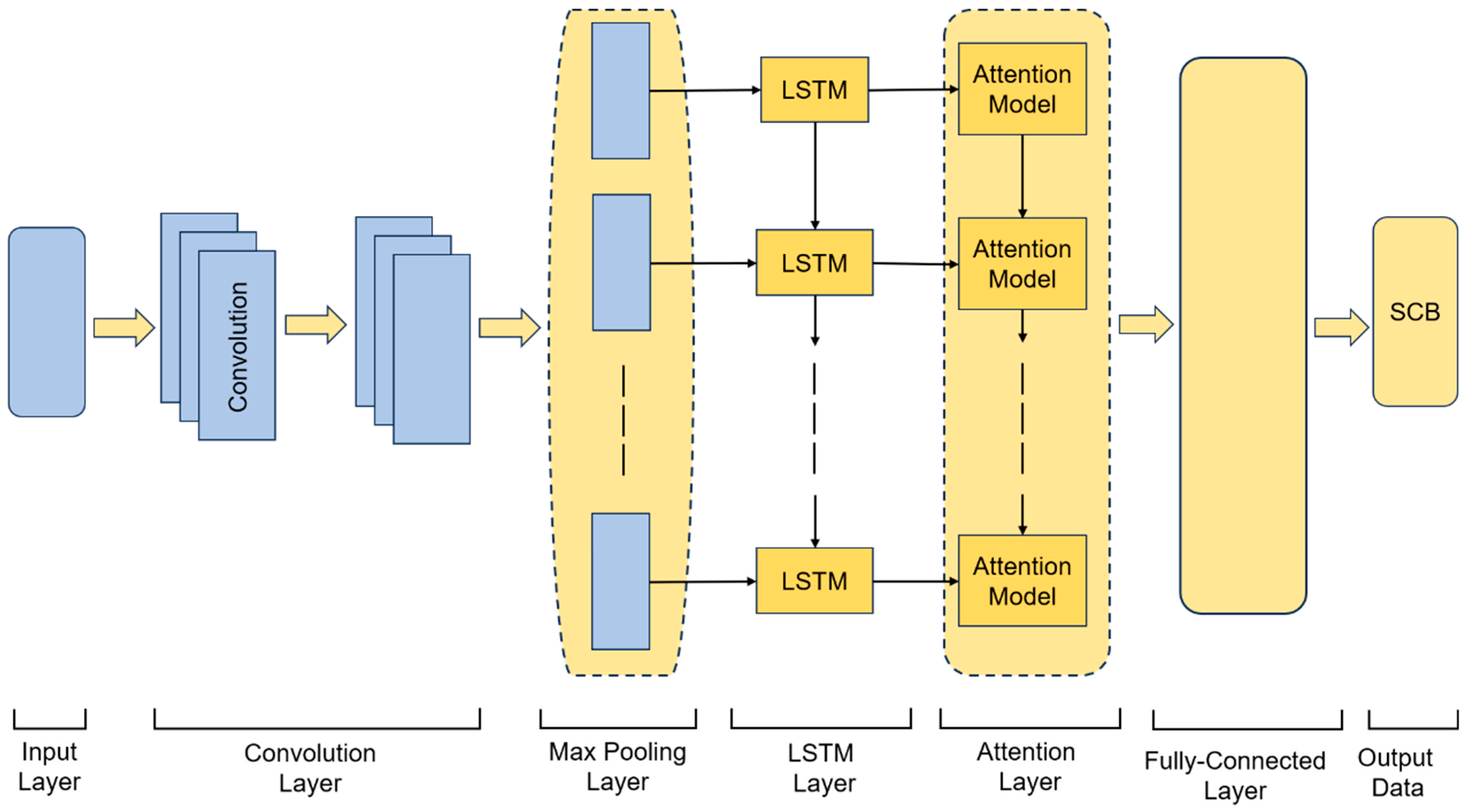

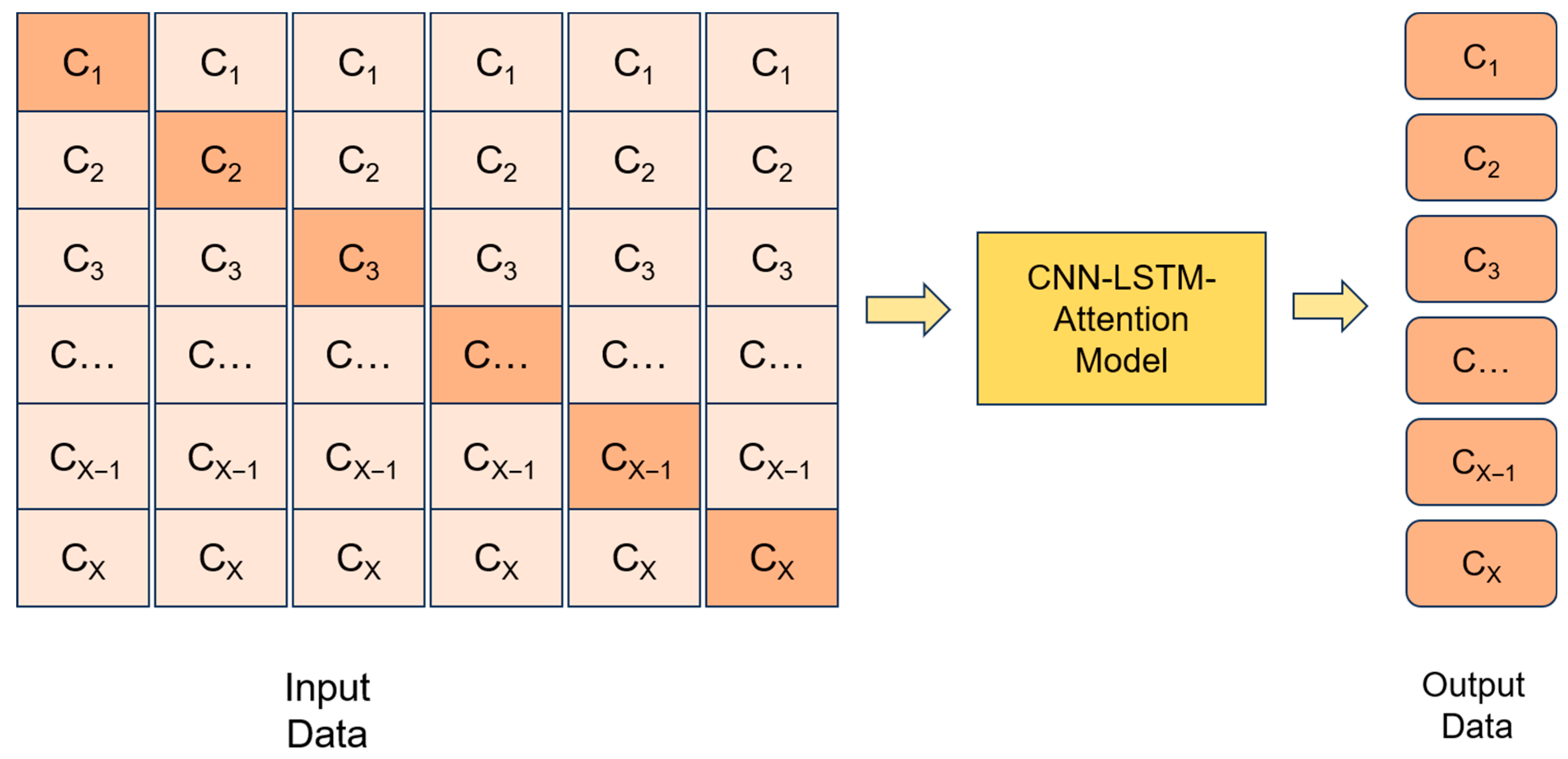

3.3. CNN-LSTM-Attention Model

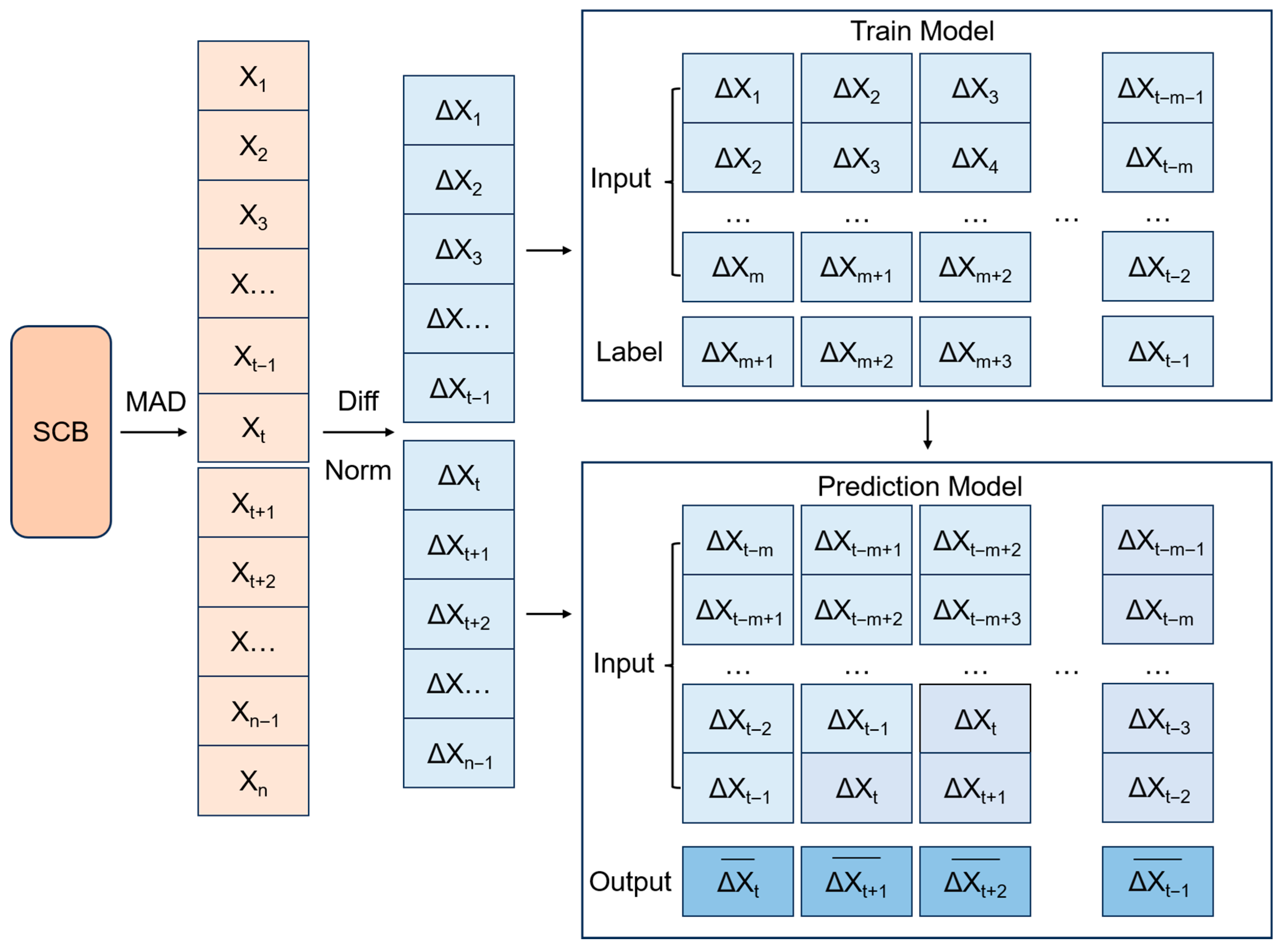

3.4. Data Pre-Processing and Parameter Settings

4. Experimentation and Analysis

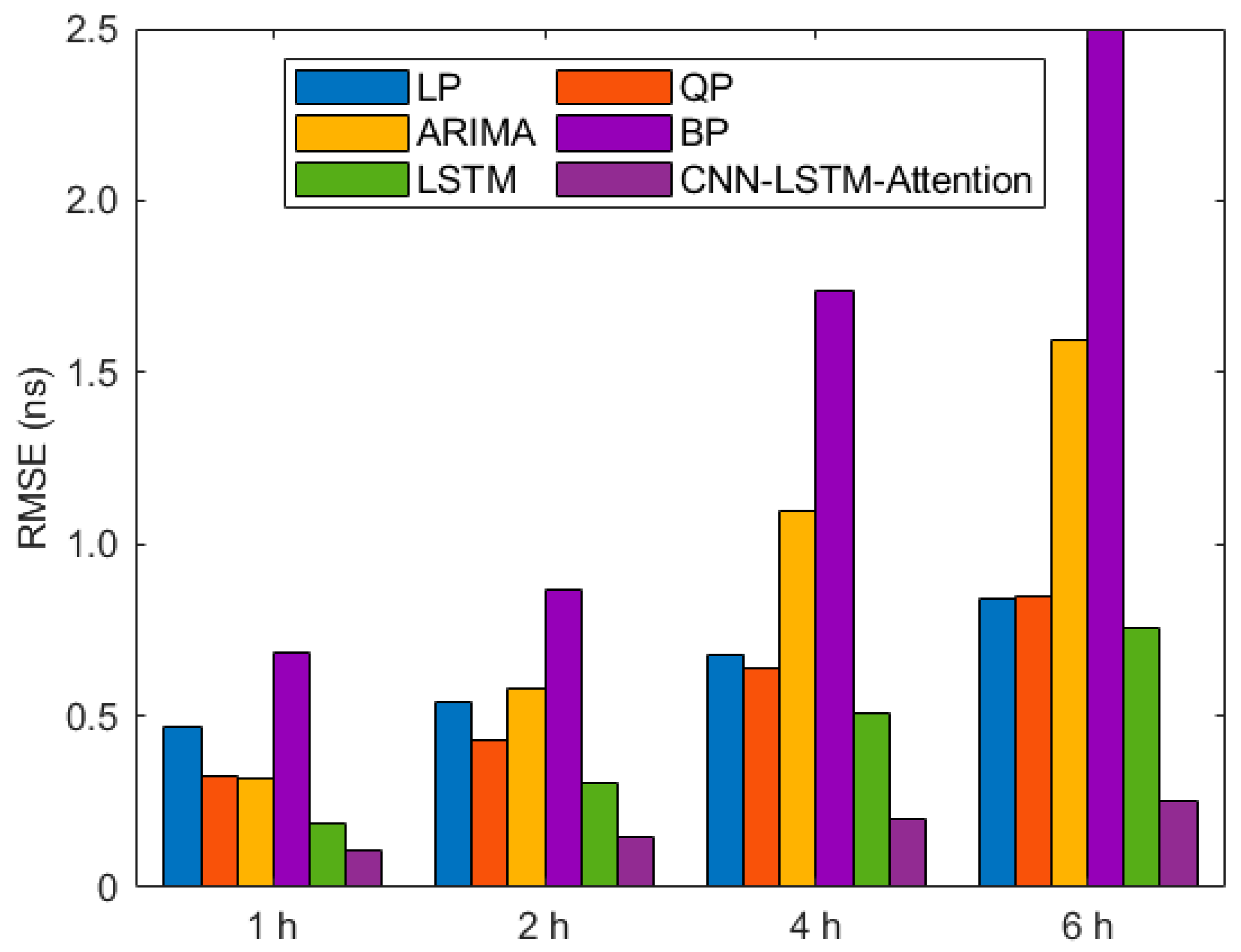

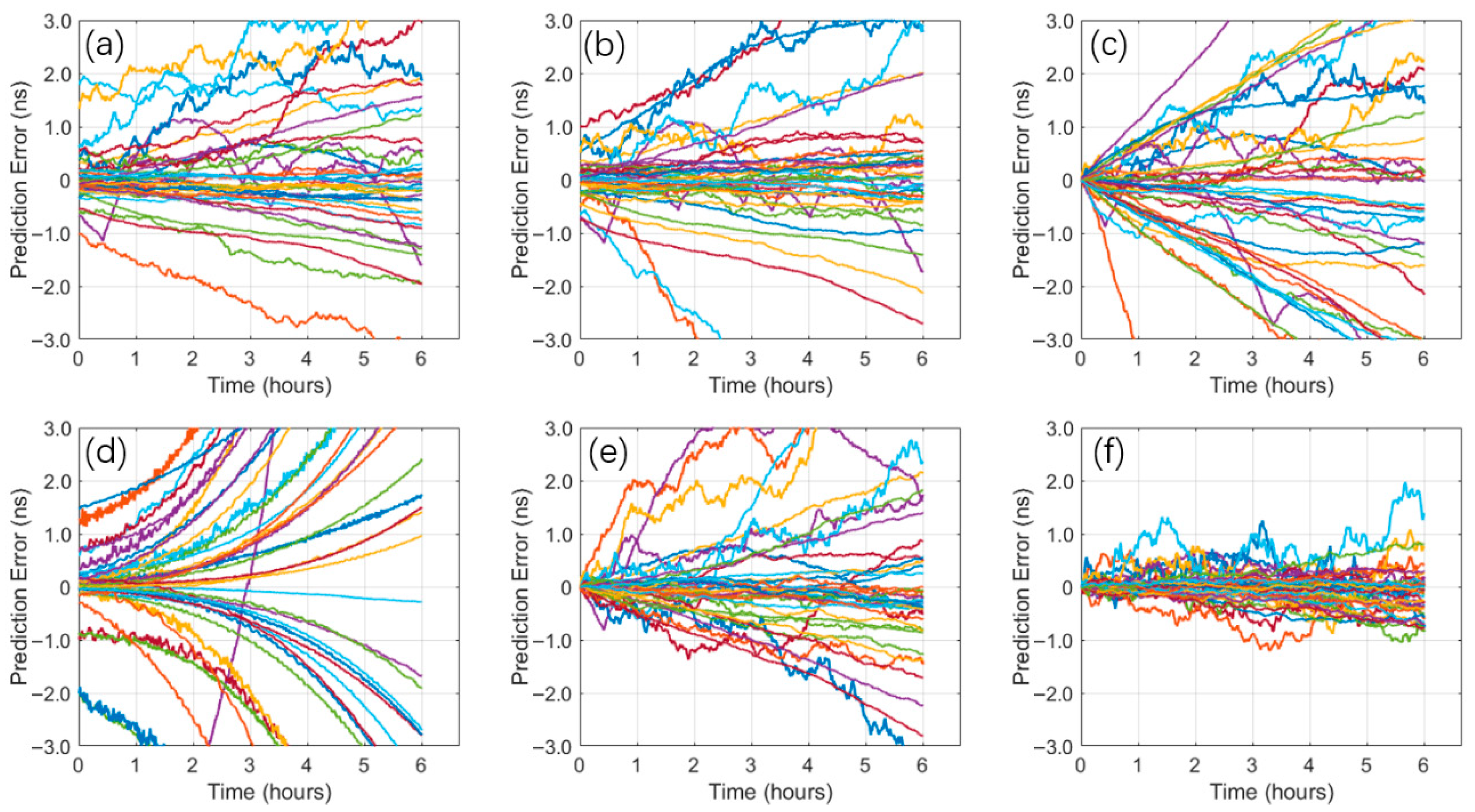

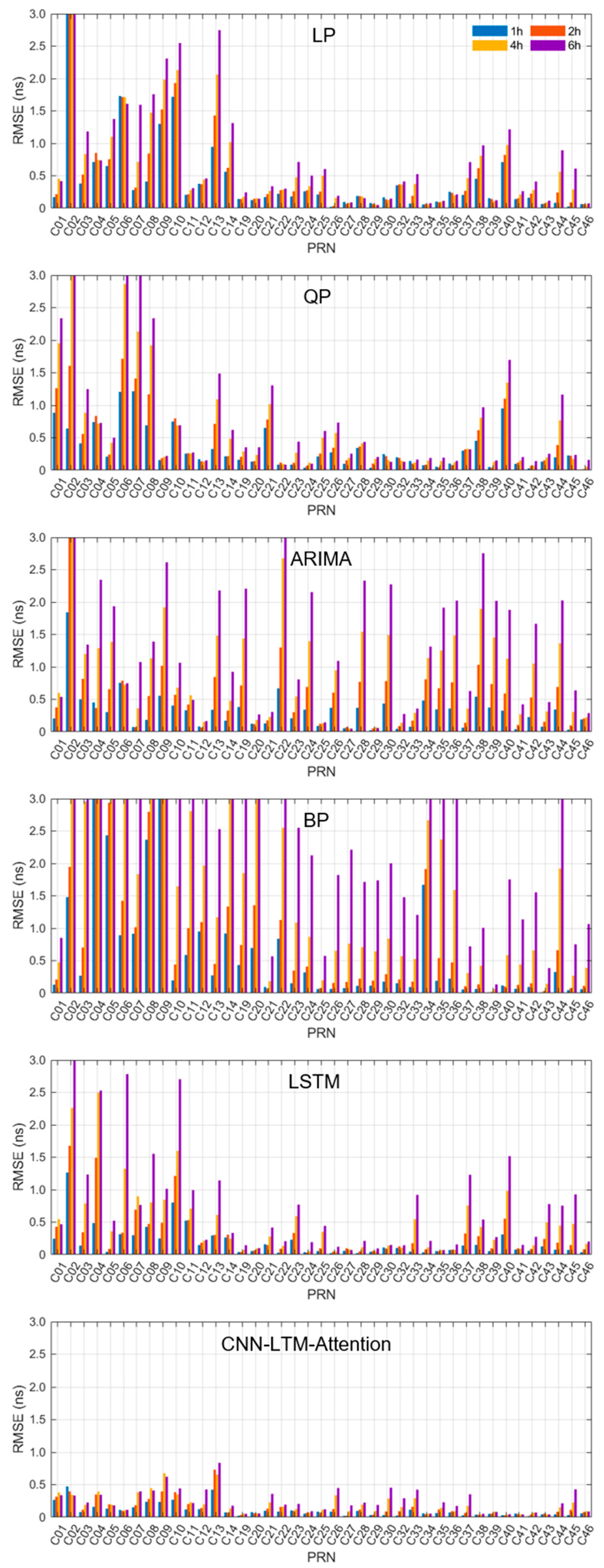

4.1. Performance Assessment of Forecasting Models

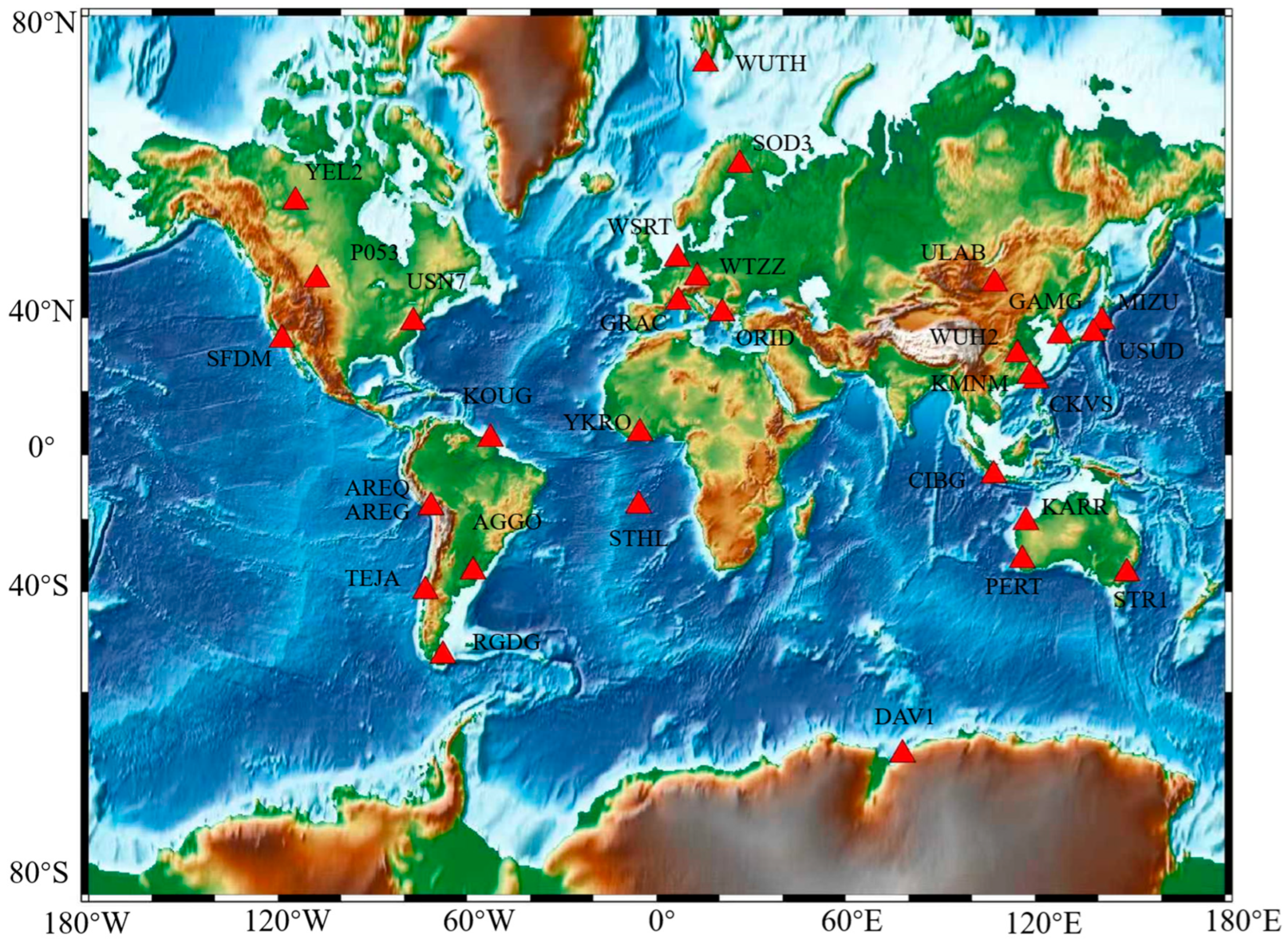

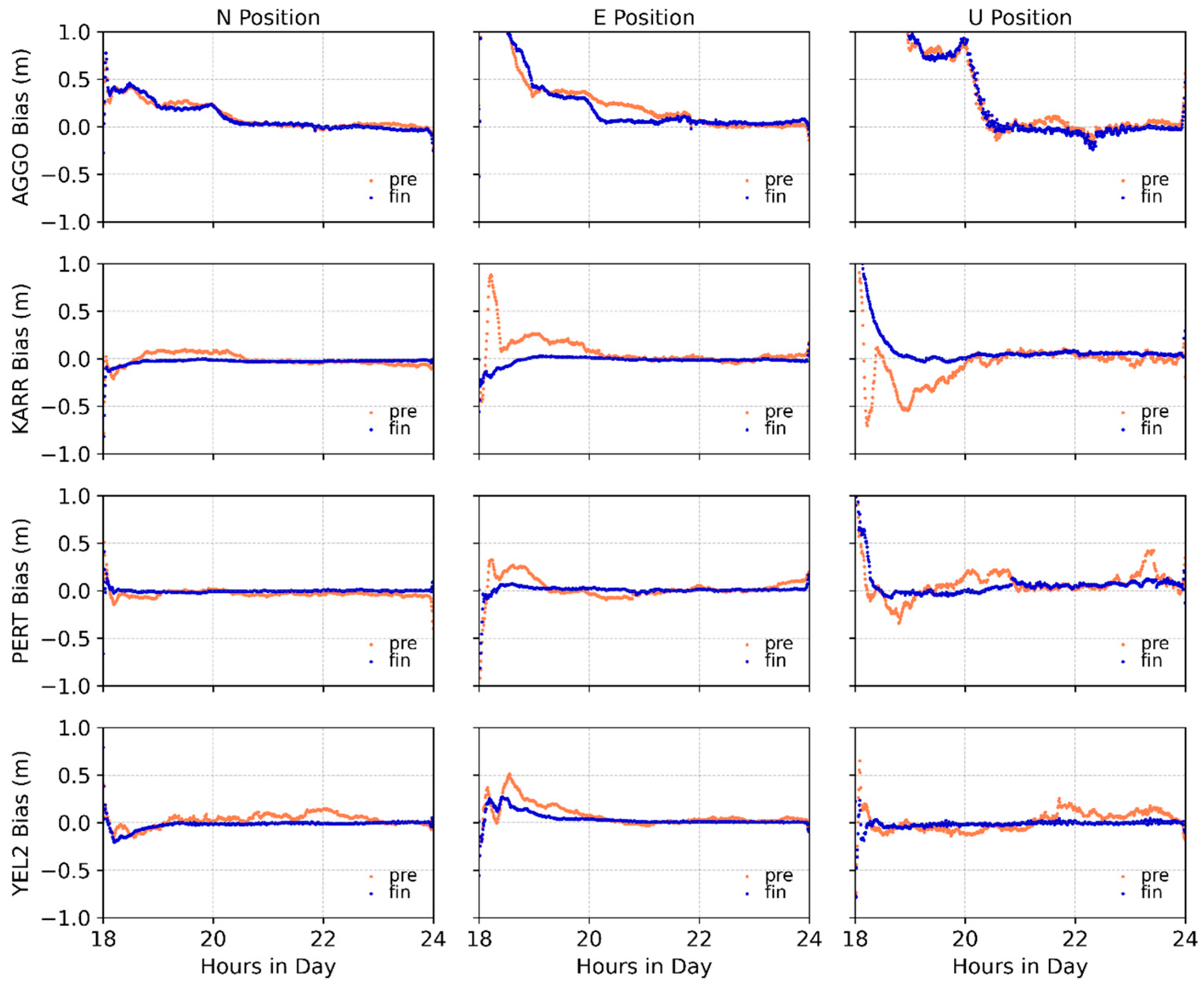

4.2. PPP Experiment

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- This paper describes the development of a hybrid model based on CNN, LSTM, and Attention mechanisms for predicting BDS SCB. In this architecture, local features extracted by the CNN layer are passed to the LSTM to model temporal dependencies. The Attention mechanism then enhances this process by adaptively weighting critical timesteps, collectively improving prediction accuracy and stability. Meanwhile, we sequentially complete the prediction tasks by leveraging the correlations among BDS satellites.

- (2)

- Regarding both accuracy and stability, the CNN-LSTM-Attention model significantly outperforms all benchmark models (LP, QP, ARIMA, BP, LSTM). Furthermore, the model excels in short-term predictions and demonstrates remarkable stability in the long term, as the RMSE for most satellites stays below 1 ns.

- (3)

- Finally, we conducted simulated real-time PPP experiments using predicted SCB data and post-processed SCB products over the same time period, performing kinematic PPP data processing for 30 selected globally distributed IGS tracking stations. Experimental results demonstrate comparable positioning accuracy between the predicted data and post-processed products in the N, E, and U directions, confirming its suitability for positioning applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geng, J.; Wen, Q.; Chen, G.; Dumitraschkewitz, P.; Zhang, Q. All-frequency IGS phase clock/bias product combination to improve PPP ambiguity resolution. J. Geod. 2024, 98, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, S.; Peng, B.; Lu, R.; Zhou, C. The effect of satellite code bias on GPS PPP time transfer. J. Spat. Sci. 2025, 70, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caissy, M.; Agrotis, L.; Weber, G. The IGS real-time service//EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2013, 15, EGU2013-11168. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, G.; Riddell, A.; Hausler, G. The international GNSS service. In Springer Handbook of Global Navigation Satellite Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Ge, M.; Neitzel, F.; Wang, X.; Yuan, H. Investigation of the performance of real-time BDS-only precise point positioning using the IGS real-time service. GPS Solut. 2019, 23, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.W.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, G.C. Real-time clock offset prediction with an improved model. GPS Solut. 2014, 18, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ji, S.; Yang, H. An approach to GPS clock prediction for real-time PPP during outages of RTS stream. GPS Solut. 2018, 22, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Hugentobler, U.; Montenbruck, O. A method to assess the quality of GNSS satellite phase bias products. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, J.; Han, X. Open-source software for multi-GNSS inter-frequency clock bias estimation. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syam, W.P.; Priyadarshi, S.; Roqué, A.A.G. Fast and reliable forecasting for satellite clock bias correction with transformer deep learning. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Precise Time and Time Interval Systems and Applications Meeting, Long Beach, CA, USA, 23–26 January 2023; pp. 76–96. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Cui, B.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, W.; Li, P. An improved predicted model for BDS ultra-rapid satellite clock offsets. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.J.; Ren, C.; Yang, X.F.; Pang, G.F.; Lan, L. A grey model based on first differences in the application of satellite clock bias prediction. Chin. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 40, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.-Y.; Chen, Y.Q.; Liu, X.S. An improved grey model and its application research on the prediction of real-time GPS satellite clock errors. Chin. Astron. Astrophys. 2009, 33, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.Y.; Dang, Y.M.; Lu, X.S.; Xu, W.M. Prediction model with periodic item and its application to the prediction of GPS satellite clock bias. Acta Astron. Sin. 2010, 51, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Bhattarai, S.; Ziebart, M. Development of a Kalman filter based GPS satellite clock time-offset prediction algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2012 European Frequency and Time Forum, Gothenburg, Sweden, 23–27 April 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.; Cai, C.-N.; Li, S.M.; Li, X.H.; Li, Z.B.; Deng, K.Q. Long-term clock bias prediction based on an ARMA model. Chin. Astron. Astrophys. 2014, 38, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewdie, G.K.; Valladares, C.; Cohen, M.B.; Lary, D.J.; Ramani, D.; Tsidu, G.M. Data-driven forecasting of low-latitude ionospheric total electron content using the random forest and LSTM machine learning methods. Space Weather 2021, 19, e2020SW002639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, L.; Xu, A.; Su, X.Q.; Liang, X.H. The application of radial basis function neural network in the GPS satellite clock bias prediction. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2014, 43, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chai, H.; Wang, C.; Xiao, G.; Chong, Y.; Guan, X. Improved wavelet neural network based on change rate to predict satellite clock bias. Surv. Rev. 2021, 53, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Liu, J.; Zhu, X.; Dai, Z.; Li, D. Research on modeling and predicting of BDS-3 satellite clock bias using the LSTM neural network model. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Ji, Z.; Zhai, R.; Xiao, C.; Yang, F.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y. Clock bias prediction algorithm for navigation satellites based on a supervised learning long short-term memory neural network. GPS Solut. 2021, 25, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Ou, G.; Tang, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, P. A Novel Long Short-Term Memory Predicted Algorithm for BDS Short-Term Satellite Clock Offsets. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2021, 2021, 4066275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Liu, M.; Li, P.; Li, Z.; Lv, K. Enhancing satellite clock bias prediction in BDS with LSTM-attention model. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wang, Z.; Kuen, J.; Ma, L.; Shahroudy, A.; Shuai, B.; Chen, T. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 77, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to forget: Continual prediction with LSTM. Neural Comput. 2000, 12, 2451–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. Comput. Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhao, L.; Li, H. BDS multiple satellite clock offset parallel prediction based on multivariate CNN-LSTM model. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J. Robust Statistics—The Approach Based on Influence Functions; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | Model | Track | Clock | PRN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDS | BDS-2 | GEO | Rb | C01 C02 C03 C04 C05 |

| MEO | C11 C12 C14 | |||

| IGSO | C06 C07 C08 C09 C10 C13 | |||

| BDS-3 | MEO | Rb | C19 C20 C21 C22 C23 C24 C32 C33 C36 C37 C41 C42 | |

| PHM | C25 C26 C27 C28 C29 C30 C34 C35 C43 C44 C45 C46 | |||

| IGSO | PHM | C38 C39 C40 |

| Stations | Latitude () | Longitude () | Stations | Latitude () | Longitude () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGGO | −34.874 | −58.140 | RGDG | −53.786 | −67.752 |

| AREG | −16.465 | −71.493 | SFDM | 34.460 | −118.755 |

| AREQ | −16.466 | −71.493 | SOD3 | 67.421 | 26.389 |

| CIBG | −6.490 | 106.849 | STHL | −15.943 | −5.667 |

| CKSV | 22.999 | 120.220 | STR1 | −35.316 | 149.010 |

| DAV1 | −68.577 | 77.973 | TEJA | −39.805 | −73.253 |

| GAMG | 35.590 | 127.920 | ULAB | 47.865 | 107.052 |

| GRAC | 43.754 | 6.921 | USN7 | 38.921 | −77.066 |

| KARR | −20.981 | 117.097 | USUD | 36.133 | 138.362 |

| KMNM | 24.464 | 118.389 | WSRT | 52.915 | 6.604 |

| KOUG | 5.098 | −52.640 | WTZZ | 49.144 | 12.879 |

| MIZU | 39.135 | 141.133 | WUH2 | 30.532 | 114.357 |

| ORID | 41.127 | 20.794 | WUTH | 77.003 | 15.539 |

| P053 | 48.726 | −107.725 | YEL2 | 62.481 | −114.481 |

| PERT | −31.802 | 115.885 | YKRO | 6.871 | −5.240 |

| No. | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loss function | MSE |

| 2 | Optimizer | Adam (learning rate = 0.001) |

| 3 | Convolutional layer filters | 64 |

| 4 | Convolutional layer kernel size | 5 |

| 5 | Convolutional layer activation | ReLU |

| 6 | LSTM Hidden Layer Size | 64 |

| 7 | Attention layer activation | Sigmoid |

| 8 | Batch size | 64 |

| 9 | Training epoch | 200 |

| 10 | Input dimension size | 64 |

| 11 | Output dimension size | 1 |

| 12 | Train/Test split ratio | 75%/25% |

| 13 | Data normalization | Min-Max scaling [0, 1] |

| Model | 1 h | 2 h | 4 h | 6 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LP | 0.465 | 0.537 | 0.680 | 0.841 |

| QP | 0.323 | 0.428 | 0.638 | 0.849 |

| ARIMA | 0.314 | 0.580 | 1.095 | 1.592 |

| BP | 0.684 | 0.865 | 1.738 | 3.945 |

| LSTM | 0.189 | 0.301 | 0.509 | 0.753 |

| CNN-LSTM-Attention | 0.107 | 0.147 | 0.201 | 0.250 |

| Prediction Task | Model | BDS-2 | BDS-3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Track | GEO | MEO | IGSO | MEO | IGSO | ||

| Clock | Rb | Rb | PHM | PHM | |||

| 1 h | LP | 1.357 | 0.381 | 1.064 | 0.190 | 0.096 | 0.440 |

| QP | 0.577 | 0.213 | 0.723 | 0.168 | 0.159 | 0.484 | |

| ARIMA | 0.660 | 0.194 | 0.385 | 0.221 | 0.234 | 0.413 | |

| BP | 2.026 | 0.819 | 1.521 | 0.268 | 0.243 | 0.064 | |

| LSTM | 0.435 | 0.311 | 0.398 | 0.087 | 0.059 | 0.171 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Attention | 0.221 | 0.106 | 0.238 | 0.063 | 0.055 | 0.040 | |

| 2 h | LP | 1.465 | 0.404 | 1.294 | 0.231 | 0.115 | 0.527 |

| QP | 0.901 | 0.206 | 0.999 | 0.194 | 0.197 | 0.587 | |

| ARIMA | 1.322 | 0.272 | 0.641 | 0.425 | 0.420 | 0.787 | |

| BP | 2.225 | 1.145 | 1.818 | 0.442 | 0.371 | 0.086 | |

| LSTM | 0.807 | 0.341 | 0.585 | 0.134 | 0.104 | 0.313 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Attention | 0.275 | 0.140 | 0.346 | 0.089 | 0.081 | 0.043 | |

| 4 h | LP | 1.660 | 0.582 | 1.680 | 0.300 | 0.189 | 0.631 |

| QP | 1.526 | 0.293 | 1.485 | 0.248 | 0.292 | 0.762 | |

| ARIMA | 2.796 | 0.398 | 1.052 | 0.839 | 0.737 | 1.493 | |

| BP | 3.486 | 2.742 | 3.099 | 1.198 | 0.964 | 0.357 | |

| LSTM | 1.291 | 0.390 | 1.015 | 0.246 | 0.213 | 0.546 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Attention | 0.301 | 0.189 | 0.437 | 0.128 | 0.153 | 0.056 | |

| 6 h | LP | 1.922 | 0.695 | 2.095 | 0.399 | 0.261 | 0.771 |

| QP | 2.020 | 0.349 | 2.085 | 0.312 | 0.381 | 0.939 | |

| ARIMA | 4.048 | 0.528 | 1.513 | 1.261 | 1.049 | 2.218 | |

| BP | 8.542 | 6.564 | 6.061 | 2.753 | 2.256 | 0.965 | |

| LSTM | 1.649 | 0.519 | 1.661 | 0.393 | 0.337 | 0.777 | |

| CNN-LSTM-Attention | 0.286 | 0.274 | 0.471 | 0.193 | 0.223 | 0.060 | |

| Stations | Prediction Data Mean/cm | Post-Processed Products Mean/cm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | E | U | N | E | U | |

| AGGO | 0.8 | 7.3 | 1.3 | −3.3 | 5.2 | 0.0 |

| AREG | 5.2 | 8.6 | −1.8 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 1.4 |

| AREQ | −0.4 | 7.9 | −3.3 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 0.6 |

| CIBG | 7.4 | −1.4 | −4.9 | 3.9 | −0.2 | −1.3 |

| CKSV | −13.9 | −3.8 | 2.7 | −1.0 | −2.5 | 2.8 |

| DAV1 | 13.3 | 4.2 | −3.2 | −4.4 | 0.3 | −0.5 |

| GAMG | −10.9 | 7.3 | 13.0 | −0.9 | −2.5 | 0.7 |

| GRAC | −0.2 | 9.7 | 5.4 | −0.5 | 2.6 | −2.4 |

| KARR | 2.8 | 0.6 | −3.9 | 5.5 | −1.1 | −2.4 |

| KMNM | −16.9 | −3.7 | 8.4 | −4.2 | −1.7 | 5.3 |

| KOUG | 45.8 | 10.8 | 9.9 | 41.0 | 5.5 | 8.0 |

| MIZU | −13 | 7.4 | −15.6 | −2.0 | −2.0 | −5.5 |

| ORID | 7.9 | 10.1 | −2.5 | 1.8 | −4.2 | 5.6 |

| P053 | −6.7 | −1.8 | 7.8 | −0.2 | 0.5 | −0.4 |

| PERT | 10.0 | 1.3 | −4.0 | 6.7 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| RGDG | 2.8 | 8.5 | 1.3 | −3.2 | 1.7 | −0.9 |

| SFDM | −11.4 | 5.4 | 8.7 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 2.9 |

| SOD3 | 10.1 | −7.4 | −9.9 | 2.3 | −0.8 | 0.1 |

| STHL | 1.4 | 8.3 | 4.5 | −2.5 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| STR1 | 6.7 | −1.7 | −8.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | −1.1 |

| TEJA | 15.5 | 16.6 | 5.4 | 7.9 | 9.7 | 4.2 |

| ULAB | 8.4 | −7.9 | 1.3 | 6.2 | −0.5 | −2.1 |

| USN7 | −14.5 | 4.5 | 6.4 | 0.5 | −1.8 | −0.6 |

| USUD | −16.1 | 10.6 | 3.7 | −2.4 | −0.9 | −1.0 |

| WSRT | 16.0 | −3.6 | 10.0 | 1.8 | −2.8 | 5.9 |

| WTZZ | 23.9 | −20.8 | 0.8 | 2.4 | −5.3 | 3.6 |

| WUH2 | −12.1 | −3.9 | 3.9 | −1.9 | −3.4 | 0.7 |

| WUTH | 11.2 | 8.4 | 0.9 | 0.1 | −0.1 | −0.5 |

| YEL2 | 5.9 | 2.0 | 5.4 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.3 |

| YKRO | −29.4 | 17.2 | −25.0 | −5.4 | 4.3 | −5.7 |

| Stations | N (cm) | E (cm) | U (cm) | Stations | N (cm) | E (cm) | U (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGGO | 2.2 | 2.2 | 5.4 | RGDG | 3.4 | 12.2 | 5.8 |

| AREG | 2.3 | 11.4 | 21.4 | SFDM | 4.2 | 10.8 | 23.5 |

| AREQ | 4.3 | 10.6 | 18.5 | SOD3 | 2.0 | 11.3 | 4.5 |

| CIBG | 4.8 | 2.3 | 15.3 | STHL | 9.5 | 9.1 | 6.8 |

| CKSV | 7.9 | 13.4 | 8.0 | STR1 | 10.6 | 3.1 | 17.0 |

| DAV1 | 15.7 | 26.5 | 32.2 | TEJA | 5.3 | 14.1 | 11.7 |

| GAMG | 9.8 | 13.7 | 35.8 | ULAB | 2.1 | 10.9 | 14.1 |

| GRAC | 5.2 | 7.0 | 11.7 | USN7 | 3.3 | 10.3 | 23.0 |

| KARR | 4.3 | 2.5 | 4.0 | USUD | 7.8 | 17.8 | 20.2 |

| KMNM | 8.4 | 15.9 | 12.7 | WSRT | 4.6 | 15.3 | 17.2 |

| KOUG | 31.3 | 32.8 | 106.7 | WTZZ | 18.1 | 23.0 | 4.0 |

| MIZU | 5.7 | 15.4 | 23.1 | WUH2 | 7.8 | 9.8 | 13.0 |

| ORID | 10.7 | 8.1 | 10.6 | WUTH | 14.0 | 13.6 | 11.2 |

| P053 | 6.5 | 5.4 | 10.2 | YEL2 | 6.8 | 3.5 | 10.2 |

| PERT | 3.5 | 2.6 | 17.2 | YKRO | 23.7 | 26.2 | 34.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, J.; Tang, J.; Teng, H.; Wu, X. Prediction and Performance of BDS Satellite Clock Bias Based on CNN-LSTM-Attention Model. Sensors 2026, 26, 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020422

Ma J, Tang J, Teng H, Wu X. Prediction and Performance of BDS Satellite Clock Bias Based on CNN-LSTM-Attention Model. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):422. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020422

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Junwei, Jun Tang, Hanyang Teng, and Xuequn Wu. 2026. "Prediction and Performance of BDS Satellite Clock Bias Based on CNN-LSTM-Attention Model" Sensors 26, no. 2: 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020422

APA StyleMa, J., Tang, J., Teng, H., & Wu, X. (2026). Prediction and Performance of BDS Satellite Clock Bias Based on CNN-LSTM-Attention Model. Sensors, 26(2), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020422