PLA/MWNTs Conductive Polymer Composites as Stress Sensors—The Role of Supramolecular Ordering

Highlights

- Developing PLA-based nanocomposite stress sensor with low MWNTs content.

- Identifying the limits of applicability of PLA/MWNTs stress sensors based on stress-induced crystallization phenomenon.

- A new approach to the development of resistive sensors based on the supramolecular ordering of PLA matrix.

- Validation of the relationship between the quantity of nanoaditive, the supramolecular structure of the polymer matrix, and the stability of the nanocomposite in assessing its sensory response to cyclic stress.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of PLA/MWNTs Conductive Polymer Composites via Precipitation Method

2.2. TGA Method

2.3. SEM Method

2.4. Mechanical Tests

2.5. Electroconductivity Tests

2.6. WAXD Supramolecular Structure Analysis

2.7. Thermal Properties Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

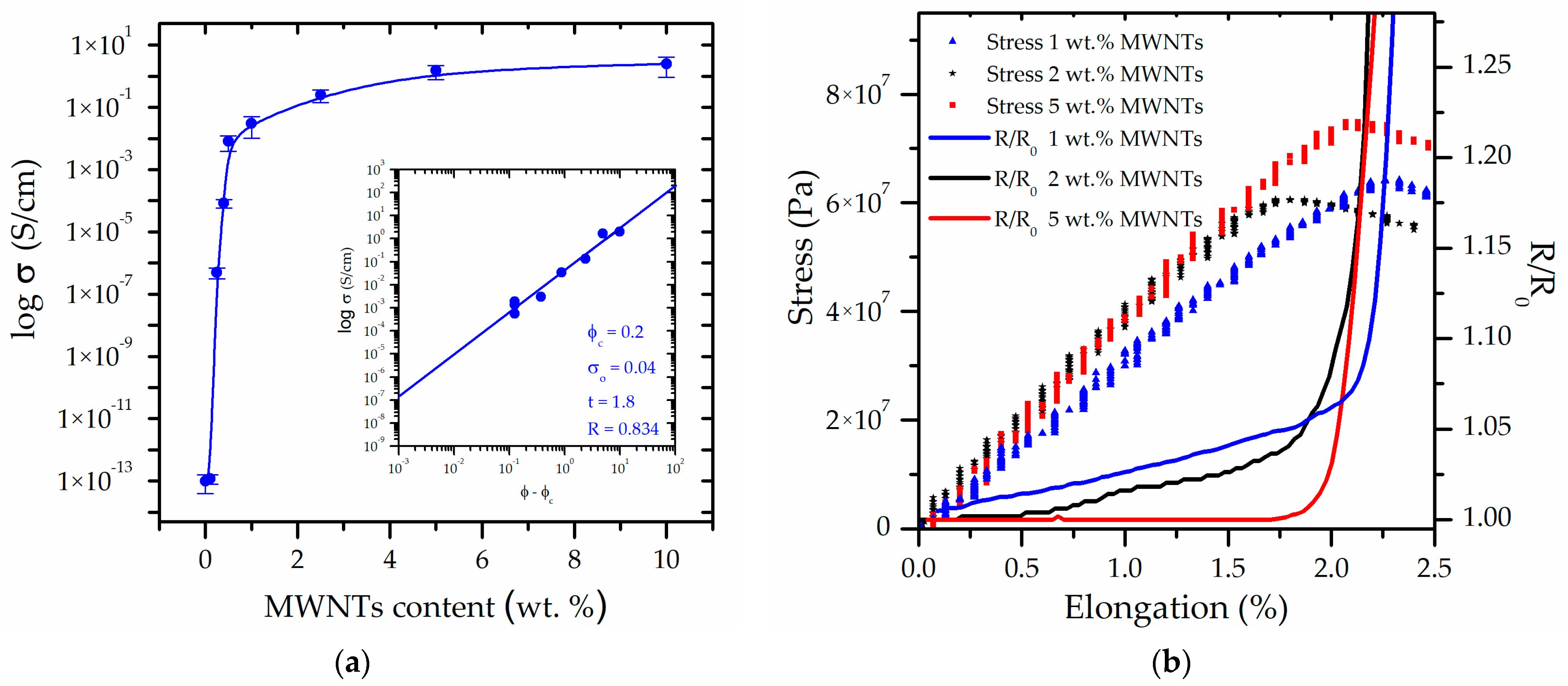

3.1. Electromechanical Sensor Investigations

3.2. Supramolecular Structural Study of PLA/MWNTs Conductive Polymer Composites

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MWNTs | Multiwall carbon nanotubes |

| CPCs | Conductive Polymer Composites |

| PLA | Polylactide |

| PLLA | Poly(l-lactide) |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| DSC | Dynamic Scanning Calorimetry |

| WAXD | Wide-angle X-ray diffractometer |

References

- Pietrzak, L.; Raniszewski, G.; Szymanski, L. Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Polylactide Composites for Electrical Engineering—Fabrication and Electrical Properties. Electronics 2022, 11, 3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dehghani-Sanij, A.A.; Blackburn, R.S. Carbon Based Conductive Polymer Composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 3408–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrul, F.; Halim, K.A.A.; Salleh, M.A.A.M.; Omar, M.F.; Osman, A.F.; Zakaria, M.S. Current Advancement in Electrically Conductive Polymer Composites for Electronic Interconnect Applications: A Short Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 701, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yin, R.; Liu, X.; He, Y.; Dai, K.; Shan, C.; Guo, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Electrically Conductive Polymer Composites for Smart Flexible Strain Sensors: A Critical Review. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2018, 6, 12121–12141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.L. Self-Powered Sensing in Wearable Electronics—A Paradigm Shift Technology. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 12105–12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gniotek, K.; Krucińska, I. The Basic Problems of Textronics. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2004, 12, 13–16. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228811244_The_basic_problems_of_textronics (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Satapathy, B.K.; Weidisch, R.; Pötschke, P.; Janke, A. Crack Toughness Behaviour of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube (MWNT)/Polycarbonate Nanocomposites. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2005, 26, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltopoulos, A.; Athanasopoulos, N.; Fotiou, I.; Vavouliotis, A.; Kostopoulos, V. Sensing Strain and Damage in Polyurethane-MWCNT Nano-Composite Foams Using Electrical Measurements. Express Polym. Lett. 2013, 7, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pötschke, P.; Andres, T.; Villmow, T.; Pegel, S.; Brünig, H.; Kobashi, K.; Fischer, D.; Häussler, L. Liquid Sensing Properties of Fibres Prepared by Melt Spinning from Poly(Lactic Acid) Containing Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krucińska, I.; Surma, B.; Chrzanowski, M.; Skrzetuska, E.; Puchalski, M. Application of melt-blown technology in the manufacturing of a solvent vapor-sensitive, non-woven fabric composed of poly(lactic acid) loaded with multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Text. Res. J. 2013, 83, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krucińska, I.; Surma, B.; Chrzanowski, M.; Skrzetuska, E.; Puchalski, M. Application of Melt-blown Technology for the Manufacture of Temperature-sensitive Nonwoven Fabrics Composed of Polymer Blends PP/PCL Loaded with Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013, 127, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balam, A.; Cen-Puc, M.; May-Pat, A.; Abot, J.L.; Avilés, F. Influence of Polymer Matrix on the Sensing Capabilities of Carbon Nanotube Polymeric Thermistors. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 29, 015012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flandin, L.; Bréchet, Y.; Cavaillé, J.Y. Electrically Conductive Polymer Nanocomposites as Deformation Sensors. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2001, 61, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stéphan, C. Electrical Properties of Singlewalled Carbon Nanotubes-PMMA Composites. AIP Conf. Proc. 2000, 544, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Tao, X.M.; Park, K.H. Electrically Conductive Fibers/Yarns with Sensing Behavior from PVA and Carbon Black. Key Eng. Mater. 2011, 462–463, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczyk, T.; Rabiej, S.; Szparaga, G.; Boguń, M.; Fraczek-Szczypta, A.; Błażewicz, S. Strength Properties of Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) Fibres Modified with Carbon Nanotubes with Respect to Their Porous and Supramolecular Structure. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2009, 17, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mamunya, Y.; Boudenne, A.; Lebovka, N.; Ibos, L.; Candau, Y.; Lisunova, M. Electrical and Thermophysical Behaviour of PVC-MWCNT Nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 1981–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, M.H. Electrically Conductive Carbon Nanotube/Polypropylene Nanocomposite with Improved Mechanical Properties. Mater. Des. 2015, 85, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidlou, S.; Huneault, M.A.; Li, H.; Park, C.B. Poly (Lactic Acid) Crystallization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1657–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giełdowska, M.; Puchalski, M.; Sztajnowski, S.; Krucińska, I. Evolution of the Molecular and Supramolecular Structures of PLA during the Thermally Supported Hydrolytic Degradation of Wet Spinning Fibers. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 10100–10112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Rahman, N.; Matsuba, G.; Nishida, K.; Kanaya, T.; Nakano, M.; Okamoto, H.; Kawada, J.; Usuki, A.; Honma, N.; et al. Crystallization and Melting Behavior of Poly (L-Lactic Acid). Macromolecules 2007, 40, 9463–9469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazuyo, D.S.; Aki Sasashige, T.; Kanamoto, T.; Hyon, S.H. Preparation of Oriented β-Form Poly(l-Lactic Acid) by Solid-State Coextrusion: Effect of Extrusion Variables. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 3601–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartier, L.; Okihara, T.; Ikada, Y.; Tsuji, H.; Puiggali, J.; Lotz, B. Epitaxial Crystallization and Crystalline Polymorphism of Polylactides. Polymer 2000, 41, 8909–8919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Kai, W.; Zhu, B.; Dong, T.; Inoue, Y. Polymorphous crystallization and multiple melting behavior of poly(L-lactide): Molecular weight dependence. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 6898–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoclet, G.; Seguela, R.; Vanmansart, C.; Rochas, C.; Lefebvre, J.-M. WAXS study of the structural reorganization of semi-crystalline polylactide under tensile drawing. Polymer 2012, 53, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiuchok, O.; Iurzhenko, M.; Kolisnyk, R.; Mamunya, Y.; Godzierz, M.; Demchenko, V.; Yermolenko, D.; Shadrin, A. Polylactide/Carbon Black Segregated Composites for 3D Printing of Conductive Products. Polymers 2022, 14, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narkis, M.; Ram, A.; Flashner, F. Electrical Properties of Carbon Black Filled Polyethylene. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1978, 18, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, Ł.; Stano, E.; Szymański, Ł. The Electromagnetic Shielding Properties of Biodegradable Carbon Nanotube–Polymer Composites. Electronics 2024, 13, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Zeng, Z.; Wu, S.; Sun, D.X.; Zhao, C.S.; Wang, Y. Poly (L-Lactic Acid)/Graphene Composite Films with Asymmetric Sandwich Structure for Thermal Management and Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernholc, J.; Brenner, D.; Buongiorno Nardelli, M.; Meunier, V.; Roland, C. Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Nanotubes. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 2002, 32, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thostenson, E.; Ren, Z.; Chou, T.-W. Advances in the Science and Technology of Carbon Nanotubes and Their Composites: A Review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2001, 61, 1899–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckeveriene, R.Y.; Zelikman, E.; Narkis, M. Hybrid Electrically Conducting Nano Composites Comprising Carbon Nanotubes/Intrinsically Conducting Polymer Systems. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Composites; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.H.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H.M. Simple Approach to Estimating the van Der Waals Interaction between Carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 195414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peigney, A.; Laurent, C.; Flahaut, E.; Bacsa, R.; Rousset, A.; Peigney, A.; Laurent, C.; Flahaut, E.; Bacsa, R.; Rousset, A. Specific Surface Area of Carbon Nanotubes and Bundles of Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon 2001, 39, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, J.H.; Terrones, M.; Mansfield, E.; Hurst, K.E.; Meunier, V. Evaluating the Characteristics of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon 2011, 49, 2581–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gårdebjer, S.; Andersson, M.; Engström, J.; Restorp, P.; Persson, M.; Larsson, A. Using Hansen Solubility Parameters to Predict the Dispersion of Nano-Particles in Polymeric Films. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 1756–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kim, J.K. Percolation Threshold of Conducting Polymer Composites Containing 3D Randomly Distributed Graphite Nanoplatelets. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobkowicz, M.J.; White, E.A.; Dorgan, J.R. Supramolecular Bionanocomposites 3: Effects of Surface Functionality on Electrical and Mechanical Percolation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 122, 2563–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Xu, L.; Yan, D.-X.; Li, Z.-M. Conductive polymer composites with segregated structures. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 1908–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Vieira, L.; dos Anjos, E.G.R.; Verginio, G.E.A.; Oyama, I.C.; Braga, N.F.; da Silva, T.F.; Montagna, L.S.; Passador, F.R. A review concerning the main factors that interfere in the electrical percolation threshold content of polymeric antistatic packaging with carbon fillers as antistatic agent. Nano Select. 2021, 3, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raniszewski, G.; Pietrzak, Ł. Optimization of Mass Flow in the Synthesis of Ferromagnetic Carbon Nanotubes in Chemical Vapor Deposition System. Materials 2021, 14, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D638-22; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Koncar, V. Smart Textiles for In Situ Monitoring of Composites; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, S. Percolation and Conduction. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1973, 45, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, D.; Aharony, A. Introduction to Percolation Theory; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiej, M. Application of Immune and Genetic Algorithms to the Identification of a Polymer Based on Its X-Ray Diffraction Curve. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2013, 46, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindeleh, A.M.; Johnson, D.J. Crystallinity and Crystallite Size Measurement in Cellulose Fibres: 2. Viscose Rayon. Polymer 1974, 15, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence Bragg—Nobel Lecture. NobelPrize.Org. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1915/wl-bragg/lecture/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Scherrer, P. Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse; Scientific Research Publishing: Munich, Germany, 1918; Volume 2, pp. 98–100. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1931994 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Holzwarth, U.; Gibson, N. The Scherrer Equation versus the “Debye-Scherrer Equation”. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Filler Weight Content (%) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Yield Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (neat PLA) | 2.77 (0.27) * | 51.3 (4.88) |

| 0.15 | 2.79 (0.26) | 51.4 (4.98) |

| 0.25 | 3.31 (0.29) | 54.1 (4.87) |

| 0.5 | 3.33 (0.31) | 54.6 (4.92) |

| 1 | 3.22 (0.30) | 58.7 (4.87) |

| 2 | 3.26 (0.31) | 57.8 (4.98) |

| 5 | 3.26 (0.29) | 65.9 (5.56) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pietrzak, Ł.; Puchalski, M. PLA/MWNTs Conductive Polymer Composites as Stress Sensors—The Role of Supramolecular Ordering. Sensors 2026, 26, 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020414

Pietrzak Ł, Puchalski M. PLA/MWNTs Conductive Polymer Composites as Stress Sensors—The Role of Supramolecular Ordering. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):414. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020414

Chicago/Turabian StylePietrzak, Łukasz, and Michał Puchalski. 2026. "PLA/MWNTs Conductive Polymer Composites as Stress Sensors—The Role of Supramolecular Ordering" Sensors 26, no. 2: 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020414

APA StylePietrzak, Ł., & Puchalski, M. (2026). PLA/MWNTs Conductive Polymer Composites as Stress Sensors—The Role of Supramolecular Ordering. Sensors, 26(2), 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020414