In this section, we evaluate the efficacy of the proposed adaptive augmentation selection and contrastive learning paradigm across two EEG decoding tasks: reconstruction and classification. We selected several widely used models for benchmarking and compared their performance with and without the integration of our algorithm.

4.3. Evaluation Methods and Metrics

To make a fair comparison, we implemented various well-acknowledged reconstructions and classification methodologies pertinent to EEG analysis. In the context of the reconstruction endeavor, our approach encompassed the following. (1) Linear: it consists of one convolution layer and one full connection layer. (2) VLAAI [

66]: it is a subject-independent speech decoder using ablation techniques, which is mainly composed of convolution layers and fully connected layers. (3) HappyQuokka [

67]: it is a pre-layer normalized feedforward transformer (FFT) architecture utilizing the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism and designing an auxiliary global conditioner to provide the subject identity. (4) FastSpeech2 [

68]: Transformer-based FastSpeech [

69] architecture has been proven to be efficient in HappyQuokka for auditory EEG regression tasks. FastSpeech2 handles the one-to-many mapping problem in non-autoregressive TTS better than FastSpeech by introducing some variation information of speech. We only used FastSpeech2’s decoder as an evaluation model in this paper. (5) NeuroBrain: as shown in

Figure 4, for the reconstruction task, we used three transposed convolutions. For the classification tasks, we employed the following methods: (1) EEGNet [

70], a compact convolutional neural network known for its effectiveness in EEG decoding, and (2) Neurobrain, where our implementation is simplified to utilize just a single transposed convolution layer.

To evaluate reconstruction results and classification results comprehensively, the following metrics were introduced to measure effectiveness.

Pearson correlation: Pearson correlation is a statistical measure that quantifies the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables X and Y, which is commonly used in baselines [

66,

67,

68]. Pearson correlation coefficient

can be expressed as

where

n denotes the number of data points. A high

indicates a positive linear relationship between reconstructed speech and real speech stimuli.

Accuracy: This metric quantifies the percentage of correctly predicted samples out of the total number of instances evaluated, thereby providing a straightforward and intuitive measure of the model’s predictive capability. We utilize this metric to assess and compare the efficacy of various models in classification tasks. It can be mathematically represented as follows:

Here, denotes True Positives, which are the positive instances correctly identified, and denotes True Negatives, referring to the negative instances that have been correctly identified. N represents the total number of samples evaluated.

SSIM: The Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) is a widely used quality assessment metric that measures the similarity between two two-dimensional matrices

x and

y. It takes into account not only the similarity in terms of point values but also their structures and luminance. It is formulated as follows:

where

and

are the variances of

x and

y,

is the covariance,

and

are variables to stabilize the division with weak denominator.

CW-SSIM: The Complex Wavelet Structural Similarity Index (CW-SSIM) [

71] is an extension of the SSIM index, designed to provide a more comprehensive assessment of image similarity by incorporating the complex wavelet transform. CW-SSIM is less sensitive to unstructured geometric distortion transformations such as scaling and rotation than SSIM and more intuitively reflects the structural similarity of two matrices. CW-SSIM is given by

where

and

denote two sets of coefficients extracted at the same spatial location in the same wavelet subbands of the two matrices being compared,

is the complex conjugate of

c, and

K is a small positive constant to improve the robustness of the CW-SSIM measure.

It is noteworthy that due to the high level of noise inherent in EEG data and the challenges associated with reconstructing it into audio format, existing studies have reported relatively low Pearson correlation coefficients (below 0.1) in the task of audio reconstruction from the SparrKULee dataset. For a more intuitive comparison, the Pearson correlation coefficient values, SSIM, and CW-SSIM metrics in the table are multiplied by 100 in this paper.

4.4. Comparison Experiments for Auditory EEG

In real-world scenarios, the deployed auditory EEG decoders are applied to decode EEG signals from unseen subjects. Therefore, we evaluate all models on the test subset, where the subjects never appear in the training subset. We first evaluate the performance of reconstructing speech signals from raw EEG signals and enhanced EEG signals on the SparrKULee dataset.

Table 1 illustrates that our approach significantly outperforms other baseline models. Specifically, our proposed model achieves a Pearson correlation of 0.07135 when incorporating noise augmentation, representing a remarkable improvement of over 29% compared to the best baseline model.

Furthermore, we explore the impact of augmentation methods. Although scale shows efficiency for most models except HappyQuokka, not all augmentation methods contribute to the models. For instance, while noise proves beneficial to our approach, it is harmful to other baseline models, and horizontal flipping diminishes the performance of all models to varying degrees. Therefore, it becomes evident that a simple ensembling of seven augmentation methods could potentially lead to a reduction in performance. Each model may have a preference for specific augmentation methods while exhibiting an aversion to others. For instance, our approach benefits most from noise, while VLAAI prefers scale and mask. Notably, HappyQuokka excels in integrating all augmentation methods. Hence, we need to ascertain the optimal augmentation integration strategy for each model.

For the WithMe dataset, which focuses on distinguishing between target stimuli and distractors in EEG signals, our findings are consistent. As depicted in

Table 2, based on Monte Carlo stability experiments, our model notably outperforms the conventional EEGNet, achieving improvements of

for seen subjects and

for unseen scenarios. Moreover, the proposed method outperforms others not only in overall classification performance but also in terms of the range between the maximum and minimum values (narrower interval), demonstrating that the selective approach exhibits stronger stability.

We employed the SPSS (version: IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0) data analysis platform to conduct statistical tests to evaluate the effectiveness based on the WithMe dataset. The statistical tests were performed on the values of TPR, TNR, FPR, and FNR, corresponding to

Table 3. Such results illustrate the relationship between observed (true) values and expected (predicted) values. The analysis encompassed three complementary statistical approaches: the chi-square test, correlation coefficient analysis, and quantitative strategy testing. The chi-square test is primarily used for categorical variables to assess whether two variables are associated or independent. A larger chi-square value indicates a stronger association between the two variables. Correlation coefficient analysis quantifies the linear relationship between the true labels and the predicted labels. A coefficient close to 1 suggests that the predicted values closely approximate the true values, whereas a coefficient near 0 indicates weak correspondence. The quantitative strategy test further serves as a statistical method to measure the quantitative relationship between predictions and actual outcomes. Together, these tests provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance and its alignment with empirical observations.

In the chi-square test, we computed the Pearson chi-square statistic, likelihood ratio, linear association, and asymptotic significance (p). For the correlation analysis (symmetrical measurement), corresponding metrics were derived, including Cramer’s V, the contingency coefficient, Gamma, Spearman’s rank correlation, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and Cohen’s kappa. Furthermore, as part of the quantitative strategy, we conducted auxiliary analyses involving Lambda, the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel statistic, the uncertainty coefficient, and Somers’ d value. From statistical test results, we can observe that all data augmentation methods exhibit highly significant statistical associations on the WithMe dataset (p < 0.001). Among them, the selective augmentation method demonstrates the best performance across all metrics, achieving the highest values in Pearson’s chi-square (962.5), likelihood ratio (812.7), and linear association (295.1), along with optimal correlation coefficients such as Cramer’s V (0.905), Spearman’s correlation (0.985), and Gamma coefficient (0.999). This highlights the superiority of the selective method in enhancing model discriminative capability. The mask augmentation and vertical flipping methods rank second and third, respectively, while time warping, though still statistically significant, shows relatively lower values across all indicators, suggesting its limited effectiveness in augmentation. Overall, there is a clear gradient in the effectiveness of different augmentation strategies, with selective augmentation, mask augmentation, and spatial transformation methods (vertical/horizontal flipping) performing better, whereas noise addition and temporal transformation methods exhibit relatively weaker enhancement effects. These findings provide empirical evidence for selecting appropriate data augmentation strategies tailored to specific tasks.

Adaptive selection for augmentation techniques. We show the weight coefficient of seven augmentation methods for the SparrKULee dataset during training in

Table 4. We observe that the weight coefficients of horizontal flipping and temporal dislocation are significantly lower than other augmentation methods in most models, which means the performance gain from these two augmentation techniques is negligible or even harmful. It is worth noting that horizontal flipping and temporal dislocation both disturb the temporal information of EEG signals, resulting in difficulty in reconstructing the right speech stimuli from out-of-order EEG data. Moreover, time warping only adjusts the length of the timeline but does not destroy the order of segments. Therefore, disturbance to the time dependency is not conducive to reconstructing speech from EEG signals.

Due to the little contribution to regression models, horizontal flipping and temporal dislocation should enjoy a low priority and even be kicked out manually during deployment. Similarly, vertical flipping seems useless to FastSpeech2 on the SparrKULee dataset. To explore an appropriate threshold, we evaluate varying threshold values that adaptively ignore enhanced output with low coefficient values. We do not take horizontal flipping and temporal dislocation into account in this experiment.

Table 5 indicates that most models fit well when the threshold is set to 0.4, where four models outperform the original ones while only two models achieve better performance under other threshold values. This suggests that removing inapplicable augmentation techniques is useful for our framework.

We make a fair comparison for augmentation integration selection strategies on SparrKULee. The results in

Table 6 demonstrate significant advantages of our adaptive selection policy. Because neither do all augmentation techniques bring improvements for all EEG reconstruction models nor is aggregating any combination of augmentation techniques efficient, it may be unsatisfactory to use a single augmentation method or to merge all enhancing ways. Especially, integrating all augmentation techniques is a disaster for VLAAI and FastSpeech2. It seems reasonable to manually select a group of integration that looked like the best. But, it is still not the best strategy most of the time. There is non-negligible defectiveness under the “Manual” strategy for most models except our approach. This suggests that there may be mutual hindrances between individual augmentation methods that perform well, which is a cost to figure out manually. By contrast, our adaptive selection strategy works for all models since it keeps taking one step forward to search for a better integration. According to the result of our strategy, the best performance of linear and HappyQuokka comes from some integration of augmentation techniques, which for VLA-AI, FastSpeech2, and our approach comes from one single augmentation method. The diversity of results sources illustrates the necessity of adaptive selection.

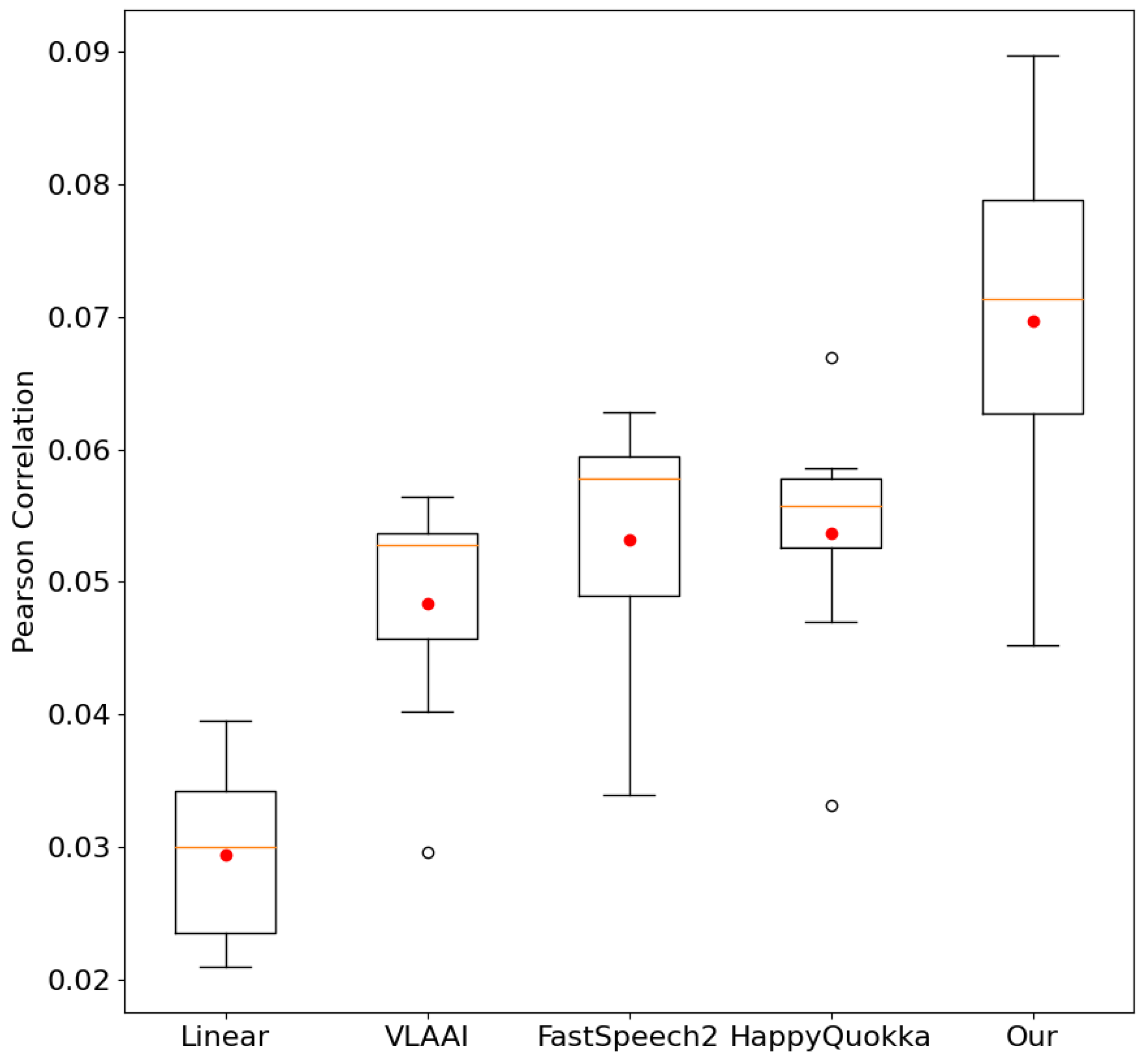

We compared our approach and baseline Pearson correlation scores across eight different subjects in the test subset. The results in

Figure 5 visually display excellent generalization and greater robustness of our proposed method over baselines. Our approach contains a high Pearson correlation when meeting EEG data from unseen subjects. This test performance suggests that our model reconstructs speech stimuli from EEG signals with higher accuracy and better diagnoses the subjects’ brain activity.

In the case of the Withme task, our observations indicate that except for “noise” augmentation, which slightly detracts from the performance of the EEGNet model, almost all augmentation techniques individually enhance performance relative to the baseline (original). Intriguingly, when employing the selective augmentation algorithm, the combination of “noise”, “scale”, and “time warping” augmentations yields the most substantial improvement for the EEGNet model. This suggests that although individual augmentations might negatively impact decoding performance, their combination with other augmentations can mitigate these adverse effects and leverage their benefits. Furthermore, for our model, NeuroBrain, when applying selective methods, we find that the ’Mask’ augmentation alone delivers the best performance.

We selected 30%, 70%, and 100% samples from the SparrKULee dataset for the training set and evaluated their regression performance on the validation set. As shown in

Table 7, as the number of training samples increases, the model’s decoding performance improves significantly. Because auditory EEG decoding is a challenging task, learning adequate EEG-to-speech features from only a small amount of data is difficult. Even when 100% of the training data are used, performance reaches only 0.1235, underscoring the critical role of data augmentation in auditory EEG decoding. It is noted that the standard deviation is up to 0.0368 when the sample size is equal to 70%. With 70% of the training samples, one split already achieves a score above 0.11, essentially on par with the performance obtained from the full 100% dataset. Thus, training the EEG decoding model on roughly 70% of the data is expected to yield near-optimal results.

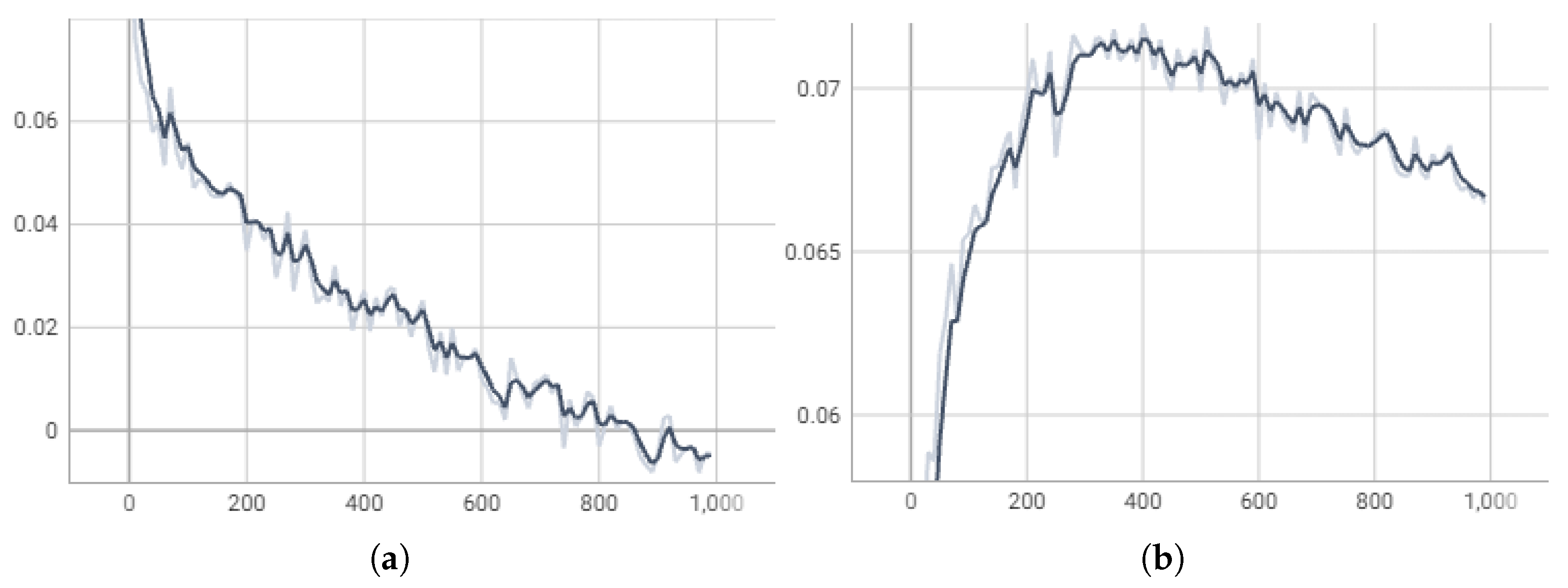

We plot the training loss and Pearson correlation for the validation set through training steps, as shown in

Figure 6. During the first 400 training steps, the training loss decreases steadily while the Pearson correlation on the validation set improves. After 400 steps, however, although the training loss continues to drop, the Pearson correlation on the validation set begins to decline. This indicates that our model started to overfit the training data beyond 400 steps, leading to degraded performance on the validation set. Therefore, we kept the checkpoint at step 400 as the final model.