Rotation-Sensitive Feature Enhancement Network for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Feature Pyramids and Multi-Scale Fusion

2.2. Attention Mechanisms in Object Detection

2.3. Loss Functions for Rotated Bounding Boxes

2.4. Comparative Analysis

3. Methods

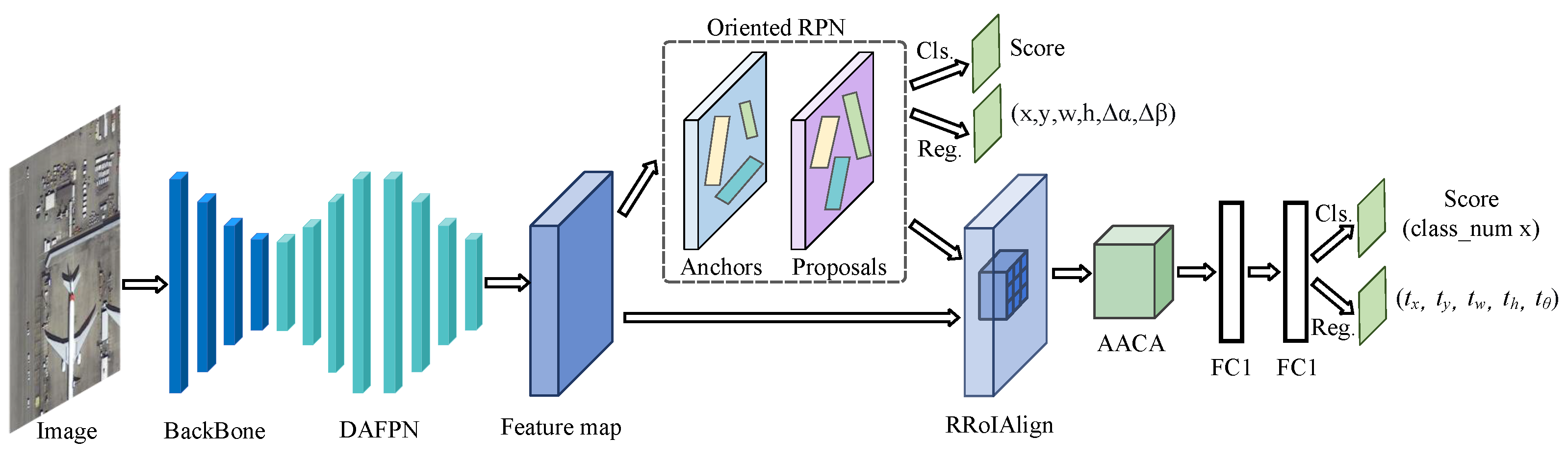

3.1. Overall Framework

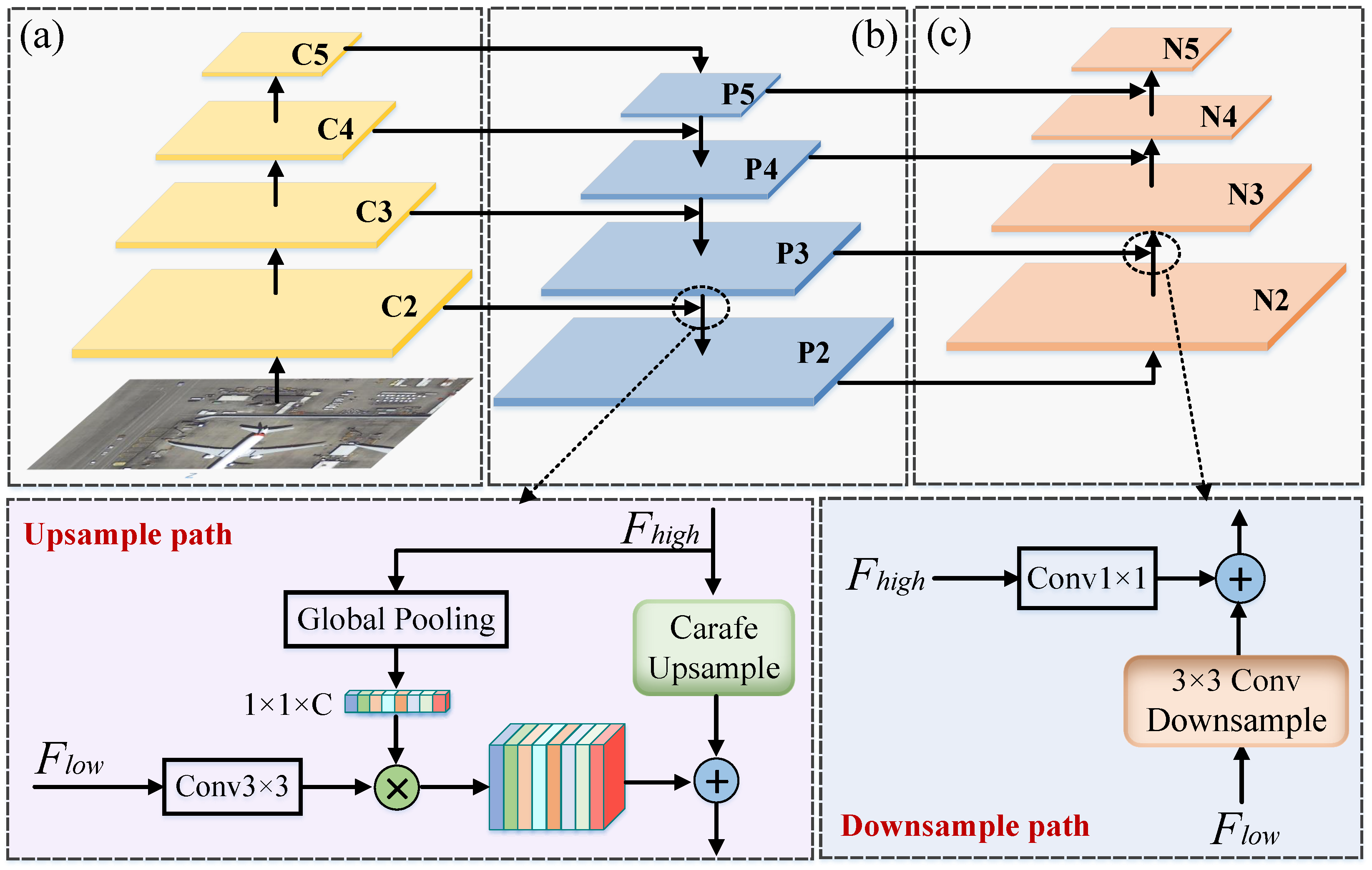

3.2. Feature Extraction and Enhancement Module

3.2.1. Backbone Feature Extraction

3.2.2. Dynamic Adaptive Feature Pyramid Network

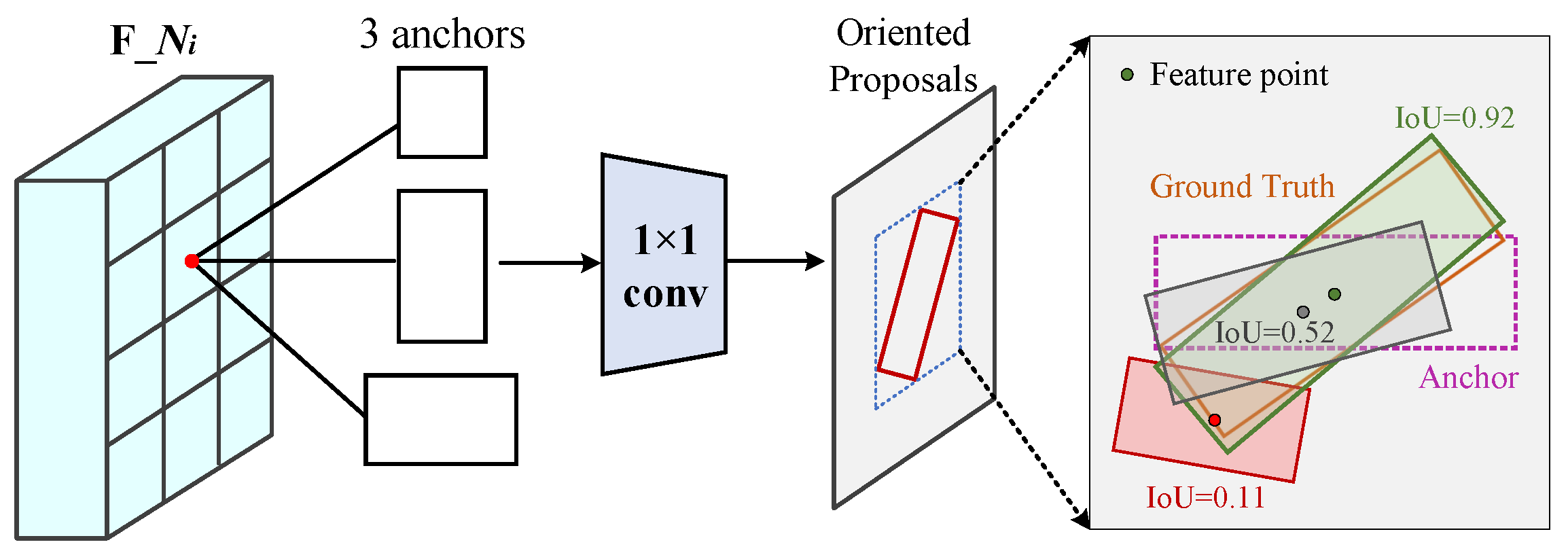

3.3. Rotated Proposal Generation and Alignment

3.3.1. Oriented Region Proposal Network

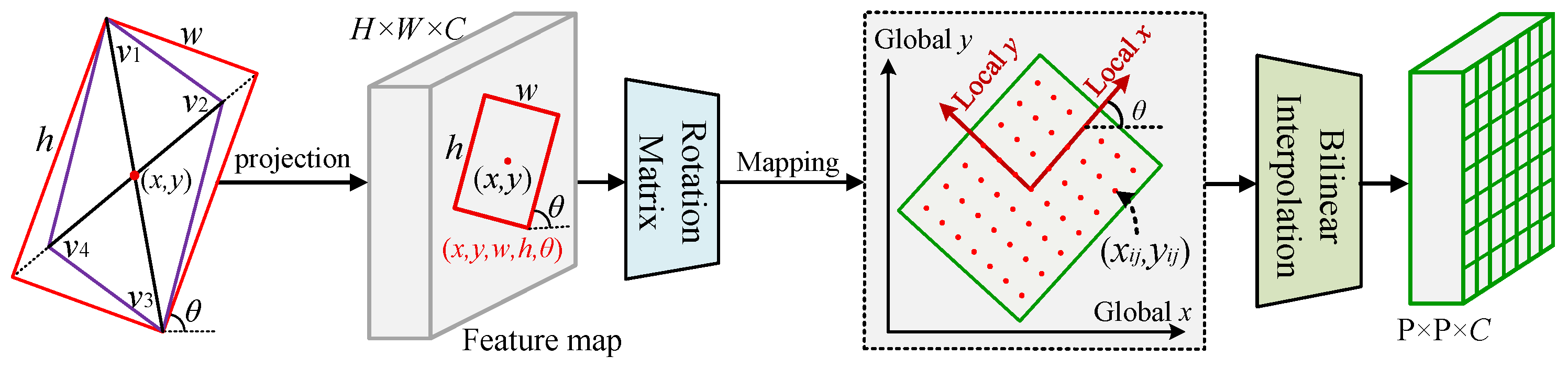

3.3.2. Rotated RoIAlign Feature Extraction

3.4. Feature Refinement and Detection Module

3.4.1. Angle-Aware Collaborative Attention

3.4.2. Detection Head

3.4.3. Loss Function

3.4.4. Training Stability and Implementation Considerations

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

4.1.1. Experimental Datasets

- (1)

- DOTA-v1.0

- (2)

- HRSC2016

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.1.3. Implementation Details

4.2. Experimental Results

4.2.1. Comparison of Detection Accuracy

4.2.2. Model Complexity and Inference Speed

4.2.3. Overall Performance Analysis

4.2.4. Stability and Robustness Analysis

4.3. Ablation Studies

4.3.1. Ablation Analysis of Core Modules

4.3.2. Verification of Module Combination Effectiveness

4.4. Visualization Analysis

4.4.1. Detection Result Visualization

4.4.2. Analysis of Heatmap Comparison Results

4.4.3. Visualization Comparison Case

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, C.; Fang, H.; Guo, S.; Tang, P.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, X.; Du, P. Detecting urban functional zones changes via multi-source temporal fusion of street view and remote sensing imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 144, 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Kong, Y.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Tian, L.; Poblete, T.; Wang, X.; Zheng, H.; Jiang, C.; Yao, X.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Mitigating the phenological influence on spectroscopic quantification of rice blast disease severity with extended PROSAIL simulations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2026, 332, 115063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, A.; White, K.; Nsutezo, S.F.; Straka, W., III; Lavista, J. Mapping global floods with 10 years of satellite radar data. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Marino, A.; Ionescu, M.; Gvilava, M.; Savaneli, Z.; Loureiro, C.; Spyrakos, E.; Tyler, A.; Stanica, A. Combining optical and SAR satellite data to monitor coastline changes in the Black Sea. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 226, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumi, A.; Cexus, J.C.; Khenchaf, A.; Abid, M. A Combined CNN-LSTM Network for Ship Classification on SAR Images. Sensors 2024, 24, 7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, G.; Zhu, P.; Tang, X.; Jia, X.; Jiao, L. Remote sensing object detection meets deep learning: A metareview of challenges and advances. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2023, 11, 8–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.L.; Zhang, Z. The YOLO framework: A comprehensive review of evolution, applications, and benchmarks in object detection. Computers 2024, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terven, J.; Córdova-Esparza, D.M.; Romero-González, J.A. A comprehensive review of yolo architectures in computer vision: From yolov1 to yolov8 and yolo-nas. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA: A large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3974–3983. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: A survey and a new benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, P.; Yan, Z.; Xu, F.; Wang, R.; Diao, W.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Feng, Y.; Xu, T.; et al. FAIR1M: A benchmark dataset for fine-grained object recognition in high-resolution remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 184, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Weng, L.; Yang, Y. A high resolution optical satellite image dataset for ship recognition and some new baselines. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods, Porto, Portugal, 24–26 February 2017; Volume 2, pp. 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Su, A.; Teng, X.; Pan, E.; Liu, M.; Yu, Q. Oriented object detection in optical remote sensing images using deep learning: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, Y.; Li, X. A comprehensive survey of oriented object detection in remote sensing images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224, 119960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Shao, W.; Ye, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Xue, X. Arbitrary-oriented scene text detection via rotation proposals. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2018, 20, 3111–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Feng, Z.; He, T. R3det: Refined single-stage detector with feature refinement for rotating object. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 3163–3171. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, K.; Zhu, J. Oriented reppoints for aerial object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 1829–1838. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Han, J. Oriented R-CNN for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3520–3529. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Xia, G.S. Align deep features for oriented object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5602511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Long, Y.; Xia, G.S.; Lu, Q. Learning RoI transformer for oriented object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–10 June 2019; pp. 2849–2858. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Zou, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q. MSDP-Net: Multi-scale Distribution Perception Network for Rotating Object Detection in Remote Sensing. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 172, 112740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.Y.; Le, Q.V. Nas-fpn: Learning scalable feature pyramid architecture for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 7036–7045. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Fu, P.; Luo, Z. R2CNN: Rotational region CNN for orientation robust scene text detection. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.09579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fu, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Xia, G.S.; Bai, X. Gliding vertex on the horizontal bounding box for multi-oriented object detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 43, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Guo, Z.; Sun, X.; Fu, K. Scrdet: Towards more robust detection for small, cluttered and rotated objects. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 8232–8241. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, K.; Lin, W.; See, J.; Yu, H.; Ke, Y.; Yang, C. Piou loss: Towards accurate oriented object detection in complex environments. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Ming, Q.; Wang, W.; Tian, Q.; Yan, J. Learning high-precision bounding box for rotated object detection via kullback-leibler divergence. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 18381–18394. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Ming, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q. Rethinking rotated object detection with gaussian wasserstein distance loss. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 11830–11841. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y. Learning spatial fusion for single-shot object detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.09516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Pan, Z.; Lei, B. Learning a rotation invariant detector with rotatable bounding box. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.09405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, H.; Fu, K.; Yang, J.; Sun, X.; Yan, M.; Guo, Z. Automatic ship detection in remote sensing images from google earth of complex scenes based on multiscale rotation dense feature pyramid networks. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Xu, R.; Liu, Z.; Loy, C.C.; Lin, D. Carafe: Content-aware reassembly of features. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3007–3016. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. Fcos: Fully convolutional one-stage object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9627–9636. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Krähenbühl, P. Objects as points. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.07850. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, J.; Lin, S.; Wei, F.; Hu, H. Gcnet: Non-local networks meet squeeze-excitation networks and beyond. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-local neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Xia, G.S. Redet: A rotation-equivariant detector for aerial object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 2786–2795. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Qi, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y. Deformable convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 764–773. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yan, J. Arbitrary-oriented object detection with circular smooth label. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 677–694. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Hou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, W.; Yan, J. Dense label encoding for boundary discontinuity free rotation detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 15819–15829. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Da, F. Phase-shifting coder: Predicting accurate orientation in oriented object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 13354–13363. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, M.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, B.; Xia, G.s.; Bai, X. Rotation-sensitive regression for oriented scene text detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 5909–5918. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Wu, P.; Liu, B.; Huang, Q.; Qu, H.; Metaxas, D. Oriented object detection in aerial images with box boundary-aware vectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Virtual, 5–9 January 2021; pp. 2150–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Xie, X.; Lang, C.; Yao, Y.; Han, J. Anchor-free oriented proposal generator for object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Pei, Z.; Zhou, F.; Wang, G. Rotated faster R-CNN for oriented object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Robot Systems and Applications, Chengdu, China, 14–16 June 2020; pp. 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Architecture | Feature Enhancement | Geometric Alignment | Loss Optimization | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oriented R-CNN | Two-stage (Anchor-based) | Standard FPN | Rotated RoIAlign | Smooth L1 (Decoupled) | Feature aliasing for rotated objects |

| S2A-Net | Single-stage (Anchor-based) | Feature Alignment | AlignConv | IoU-Smooth L1 | Lacks directional priors in attention |

| R3Det | Single-stage (Refinement) | Refinement Network | Iterative Regression | Smooth L1 + IoU | Performance drops on dense small objects |

| KLD/GWD | Loss Plugin | - | Gaussian modeling | KLD/GWD | Approximation errors for extreme aspect ratios |

| RSFPN (Ours) | Two-stage (Enhanced) | DAFPN | Rotated RoIAlign+AACA | GC-MTL | Solves the above via unified design |

| Symbol | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Anchor box | Center coordinates, width, and height of the anchor box | |

| Anchor offsets | Offsets for center and size regression | |

| Rotation offsets | Offsets for rotation characteristics | |

| Rotated proposal | Predicted center, width, height, and rotation offsets | |

| Rotated bounding box | Final representation after rectification (: rotation angle) |

| Code | Category | Train Instances | Val Instances |

|---|---|---|---|

| PL | Plane | 26,128 | 7633 |

| BD | Bridge | 1435 | 445 |

| GTF | Ground Track Field | 4860 | 1565 |

| SV | Small Vehicle | 59,660 | 17,758 |

| LV | Large Vehicle | 16,996 | 5408 |

| SH | Ship | 41,950 | 12,364 |

| TC | Tennis Court | 6456 | 2067 |

| BC | Basketball Court | 1498 | 472 |

| ST | Storage Tank | 18,186 | 5744 |

| SBF | Soccer Ball Field | 4523 | 1423 |

| RA | Roundabout | 4402 | 1390 |

| HA | Harbor | 12,628 | 3869 |

| SP | Swimming Pool | 5339 | 1678 |

| HE | Helicopter | 1654 | 524 |

| CC | Container Crane | 1438 | 450 |

| Total | 206,753 | 63,790 |

| Methods | mAP | PL | BD | GTF | SV | LV | SH | TC | BC | ST | SBF | RA | HA | SP | HE | CC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FR-O [7] | 54.13 | 79.42 | 31.66 | 57.69 | 46.71 | 46.59 | 75.02 | 89.64 | 78.11 | 59.44 | 47.7 | 48.91 | 53.56 | 66.9 | 44.63 | 32.57 |

| R-DFPN [36] | 57.94 | 80.95 | 47.73 | 62.34 | 55.45 | 50.05 | 75.54 | 90.85 | 77.6 | 64.82 | 56.24 | 51.76 | 56.69 | 71.29 | 48.62 | 47.39 |

| RRD [52] | 61.01 | 88.52 | 54.32 | 70.15 | 59.78 | 63.45 | 78.91 | 90.23 | 80.12 | 72.34 | 61.87 | 56.43 | 62.18 | 74.56 | 57.29 | 52.67 |

| RoI Trans. [21] | 69.56 | 88.64 | 65.74 | 78.52 | 66.74 | 73.01 | 83.59 | 90.74 | 77.27 | 81.46 | 63.53 | 58.39 | 67.9 | 75.41 | 62.74 | 58.39 |

| Gliding Vertex [28] | 69.3 | 89.64 | 63.55 | 72.02 | 62.25 | 73.47 | 82.36 | 90.84 | 85 | 79.02 | 59.26 | 65.5 | 64.18 | 73 | 68.16 | 51.88 |

| R3Det [17] | 71.23 | 89.87 | 66.92 | 80.45 | 69.31 | 76.18 | 85.27 | 90.68 | 86.45 | 83.17 | 68.94 | 66.73 | 71.52 | 80.89 | 70.38 | 62.15 |

| CSL [49] | 72.15 | 90.02 | 68.41 | 81.73 | 70.85 | 77.62 | 86.39 | 90.72 | 87.28 | 84.05 | 69.87 | 67.94 | 73.16 | 82.47 | 71.83 | 63.92 |

| DCL [50] | 72.89 | 90.21 | 69.27 | 82.56 | 71.93 | 78.45 | 87.12 | 90.81 | 88.03 | 84.78 | 70.65 | 68.72 | 74.31 | 83.25 | 72.69 | 64.87 |

| ReDet [47] | 73.48 | 90.83 | 67.73 | 82.66 | 72.54 | 78.31 | 87.38 | 90.9 | 87.84 | 85.26 | 70.48 | 68.42 | 74.12 | 83.92 | 73.68 | 65.74 |

| S2A-Net [20] | 74.12 | 89.11 | 71.11 | 78.39 | 68.16 | 75.01 | 84.98 | 90.86 | 87.81 | 83.53 | 71.11 | 64.16 | 72.76 | 81.32 | 73.27 | 60.06 |

| BBAVectors [53] | 74.35 | 90.45 | 71.89 | 83.27 | 73.42 | 79.16 | 87.95 | 90.88 | 88.72 | 85.63 | 71.84 | 69.58 | 75.43 | 84.71 | 74.35 | 66.92 |

| GWD [33] | 74.78 | 90.62 | 72.34 | 83.95 | 73.87 | 79.63 | 88.27 | 90.91 | 89.15 | 85.94 | 72.31 | 70.12 | 76.08 | 85.22 | 74.98 | 67.45 |

| KLD [32] | 75.23 | 90.78 | 72.86 | 84.52 | 74.35 | 80.17 | 88.64 | 90.93 | 89.63 | 86.32 | 72.89 | 70.75 | 76.72 | 85.83 | 75.61 | 68.13 |

| Oriented R-CNN [19] | 75.87 | 90.41 | 71.23 | 85.59 | 75.24 | 80.39 | 88.79 | 91.25 | 90.85 | 85.54 | 73.88 | 70.53 | 77.87 | 87.65 | 78.47 | 68.29 |

| AOPG [54] | 76.45 | 91.12 | 73.28 | 86.25 | 76.13 | 81.42 | 89.35 | 91.05 | 90.78 | 87.15 | 74.86 | 72.34 | 79.03 | 87.52 | 79.91 | 70.23 |

| Oriented RepPoints [18] | 76.78 | 91.25 | 73.65 | 86.57 | 76.49 | 81.78 | 89.62 | 91.12 | 91.4 | 87.46 | 75.23 | 72.71 | 79.41 | 87.89 | 80.34 | 70.65 |

| Rotated Faster R-CNN [55] | 77.15 | 91.38 | 73.92 | 86.83 | 76.82 | 82.13 | 89.87 | 91.25 | 91.27 | 87.75 | 75.58 | 73.05 | 79.76 | 88.4 | 80.75 | 71.02 |

| RSFPN (Ours) | 77.42 | 90.15 | 74.25 | 87.12 | 77.15 | 82.45 | 90.12 | 90.45 | 90.12 | 88.03 | 75.94 | 73.48 | 80.15 | 86.85 | 81.23 | 71.46 |

| Methods | RRD [52] | R3Det [17] | Gliding Vertex [28] | ReDet [47] | Oriented R-CNN [19] | S2A-Net [20] | RSFPN (Ours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP50 | 84.3 | 88.9 | 88.2 | 90.4 | 90.5 | 90.1 | 91.85 |

| Methods | Backbone | mAP@0.5 | Params (M) | GFLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RoI Trans. [21] | ResNet-101 | 69.56 | 43.7 | 225.3 | 11.8 |

| Gliding Vertex [28] | ResNet-101 | 69.3 | 44.2 | 228.1 | 12.3 |

| R3Det [17] | ResNet-101 | 71.23 | 43.9 | 226.8 | 12.6 |

| ReDet [47] | ReResNet-50 | 73.48 | 45.2 | 231.6 | 13.1 |

| CSL [49] | ResNet-50 | 72.15 | 42.1 | 219.5 | 14.2 |

| DCL [50] | ResNet-50 | 72.89 | 42.3 | 220.7 | 14.1 |

| S2A-Net [20] | ResNet-50 | 74.12 | 42.8 | 218.9 | 14.6 |

| BBAVectors [53] | ResNet-50 | 74.35 | 41.9 | 217.3 | 14.8 |

| GWD [33] | ResNet-50 | 74.78 | 42 | 217.8 | 14.7 |

| KLD [32] | ResNet-50 | 75.23 | 42.1 | 218.2 | 14.6 |

| Oriented R-CNN [19] | ResNet-50 | 75.87 | 41.5 | 215.7 | 15.2 |

| AOPG [54] | ResNet-50 | 76.45 | 42.6 | 222.3 | 14.3 |

| Oriented RepPoints [18] | ResNet-50 | 76.78 | 43.1 | 224.8 | 13.9 |

| Rotated Faster R-CNN [55] | ResNet-50 | 77.15 | 43.8 | 227.1 | 13.5 |

| RSFPN (Ours) | ResNet-50 | 77.42 | 42.3 | 218.9 | 14.5 |

| Experimental Setting | mAP | Gain (%) | Params (M) | FPS | SV (AP) | LV (AP) | SH (AP) | BD (AP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Oriented R-CNN) | 75.87 | – | 41.8 | 15.2 | 75.24 | 80.39 | 88.79 | 71.23 |

| + DAFPN | 76.92 | +1.05 | 42.3 | 14.8 | 76.85 (+1.61) | 81.25 (+0.86) | 89.25 (+0.46) | 72.85 (+1.62) |

| + DAFPN + AACA | 77.56 | +0.64 | 42.5 | 14.6 | 77.05 (+0.20) | 81.85 (+0.60) | 89.85 (+0.60) | 73.85 (+1.00) |

| + DAFPN + AACA + GC-MTL | 77.42 | +1.55 | 42.5 | 14.5 | 77.15 (+0.10) | 82.45 (+0.60) | 90.12 (+0.27) | 74.25 (+0.40) |

| DAFPN | AACA | GC-MTL | mAP | Gain (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| × | × | × | 75.87 | – | Baseline |

| ✓ | × | × | 76.92 | +1.05 | Only DAFPN |

| × | ✓ | × | 76.35 | +0.48 | Only AACA |

| × | × | ✓ | 76.08 | +0.21 | Only GC-MTL |

| ✓ | ✓ | × | 77.56 | +1.69 | DAFPN+AACA |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 77.42 | +1.55 | Full RSFPN |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Huo, H.; Kang, S.; Mei, A.; Zhang, C. Rotation-Sensitive Feature Enhancement Network for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Sensors 2026, 26, 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020381

Xu J, Huo H, Kang S, Mei A, Zhang C. Rotation-Sensitive Feature Enhancement Network for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):381. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020381

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jiaxin, Hua Huo, Shilu Kang, Aokun Mei, and Chen Zhang. 2026. "Rotation-Sensitive Feature Enhancement Network for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images" Sensors 26, no. 2: 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020381

APA StyleXu, J., Huo, H., Kang, S., Mei, A., & Zhang, C. (2026). Rotation-Sensitive Feature Enhancement Network for Oriented Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Sensors, 26(2), 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020381