Experimental Study on Dual-Structure Polymer Optical Fiber Sensors for Turbidity Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sensor and Experimental Procedure

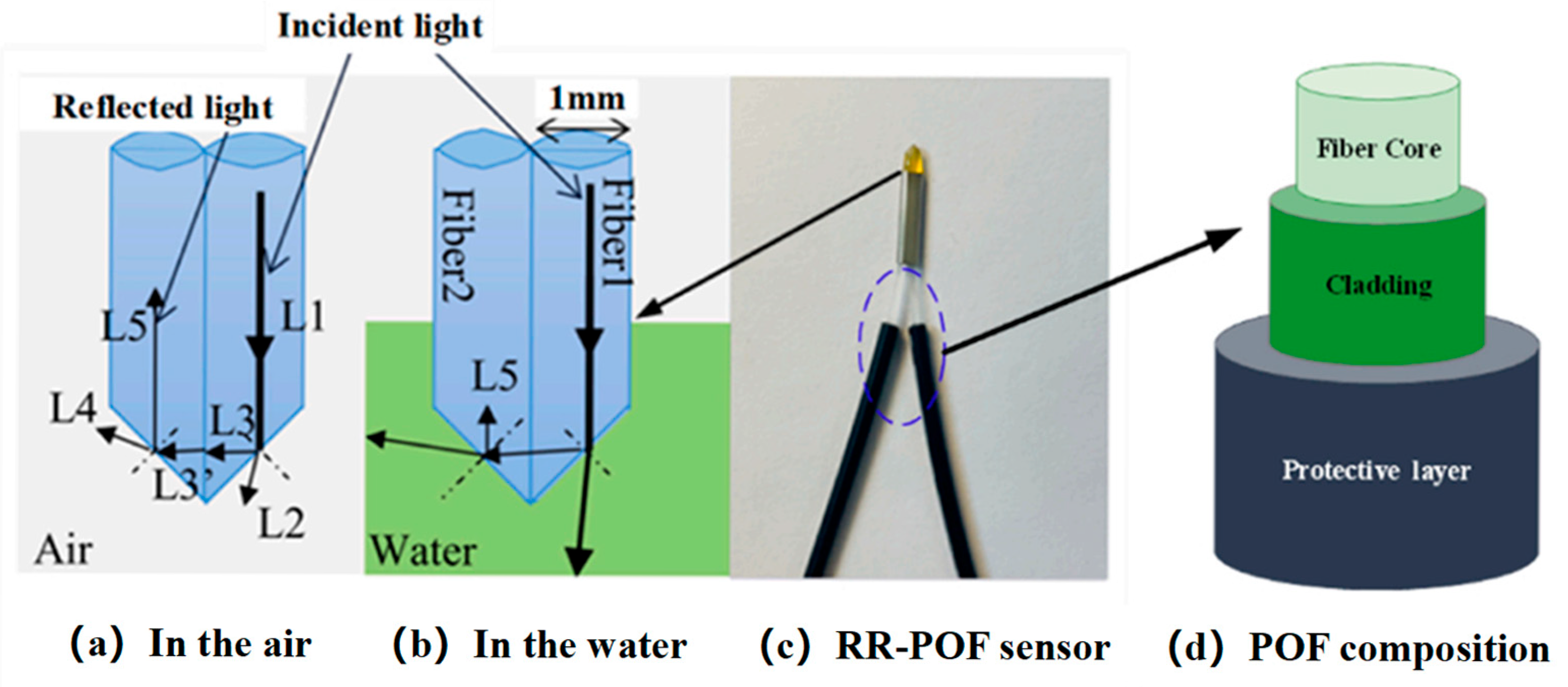

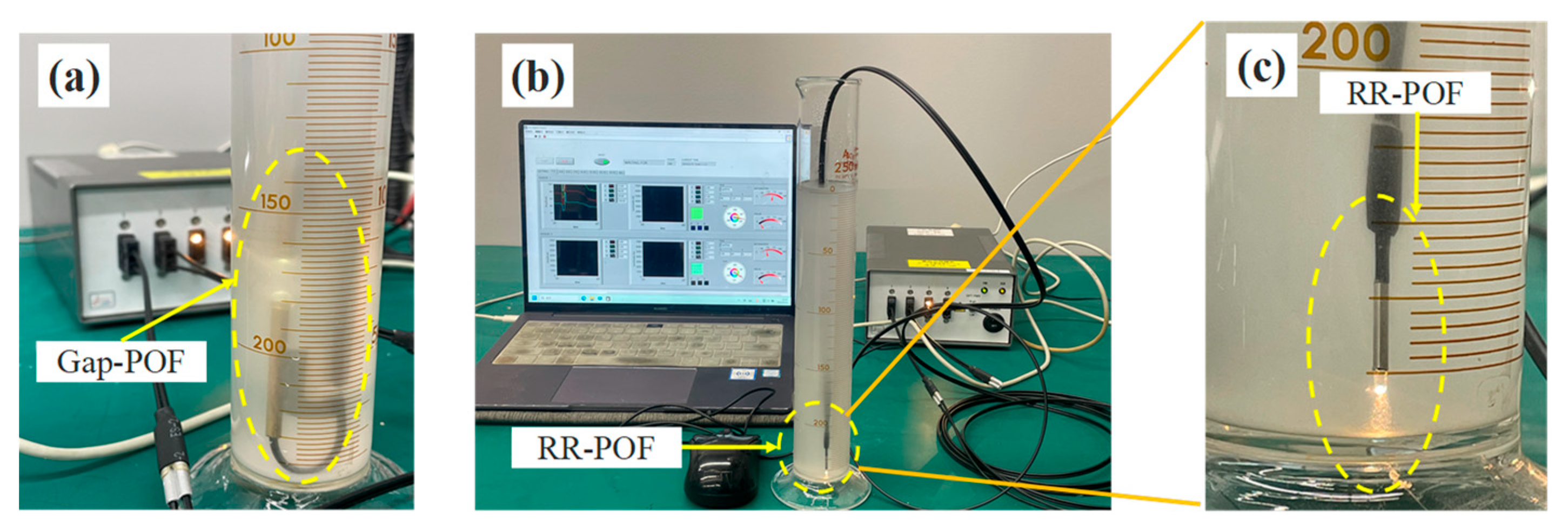

2.1. Introduction of POF Sensors

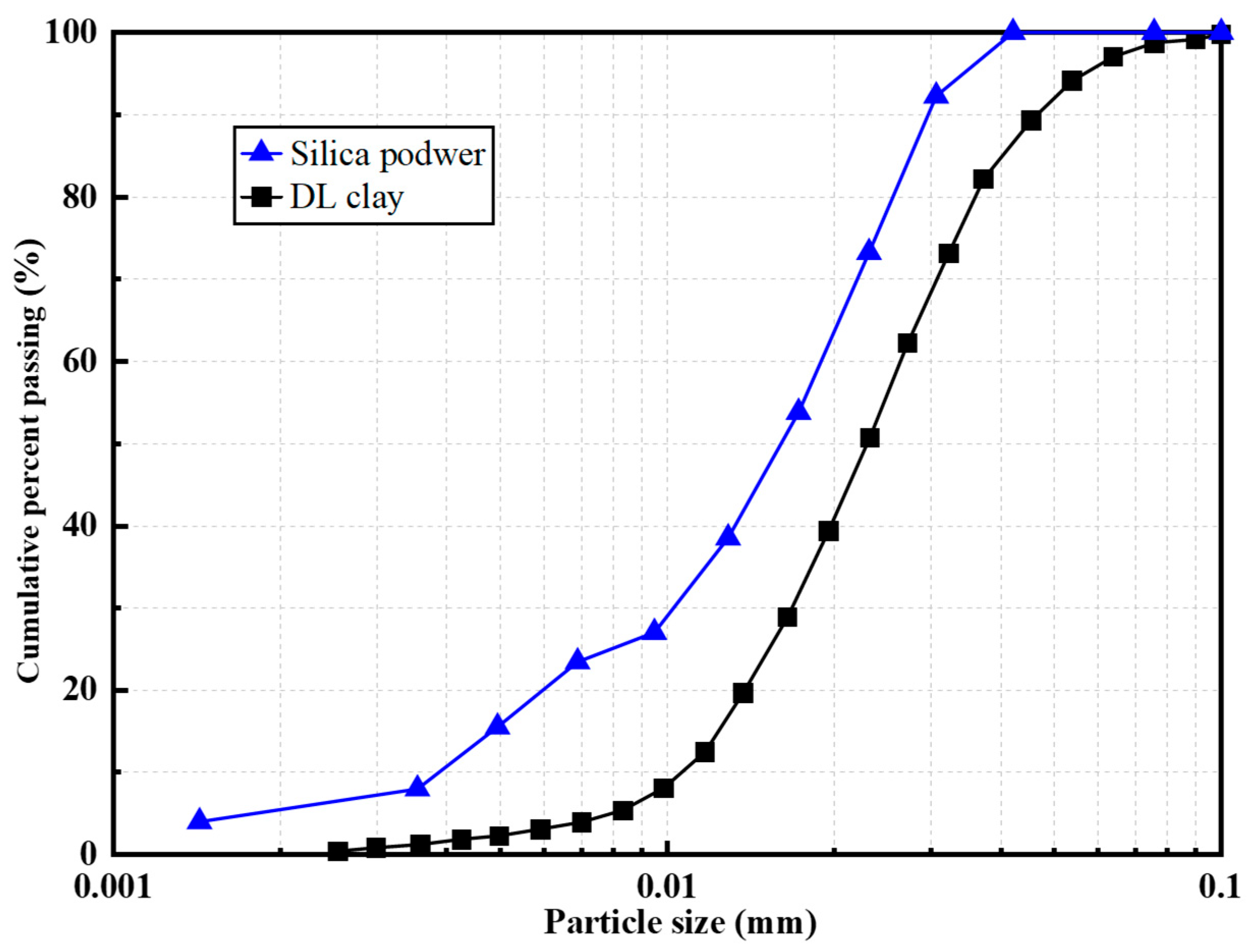

2.2. Experimental Materials

3. Experimental Monitoring Results

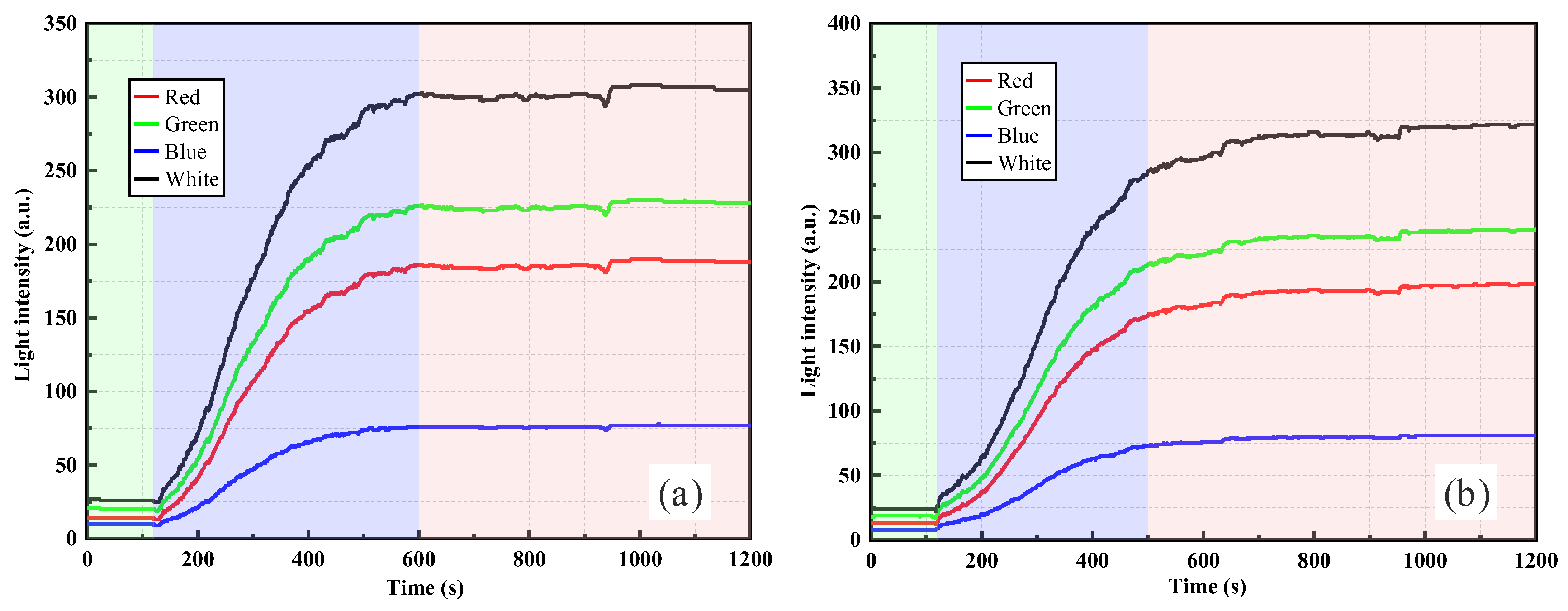

3.1. RR-POF Turbidity Monitoring

3.1.1. Monitoring of Silica Powder Suspensions by RR-POF

3.1.2. Monitoring of Clay Particle Suspensions by RR-POF

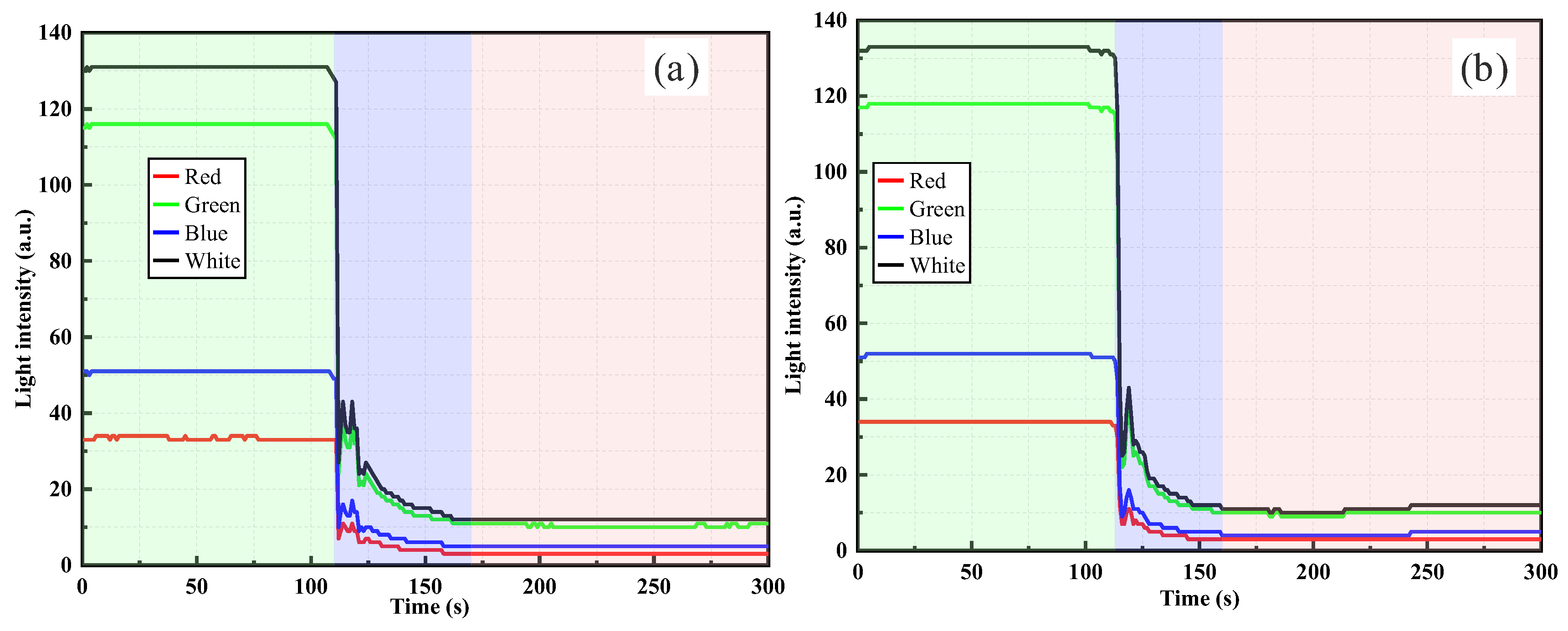

3.2. Gap-POF Turbidity Monitoring

3.2.1. Monitoring of Silica Powder Suspensions by Gap-POF

3.2.2. Monitoring of Clay Particle Suspensions by Gap-POF

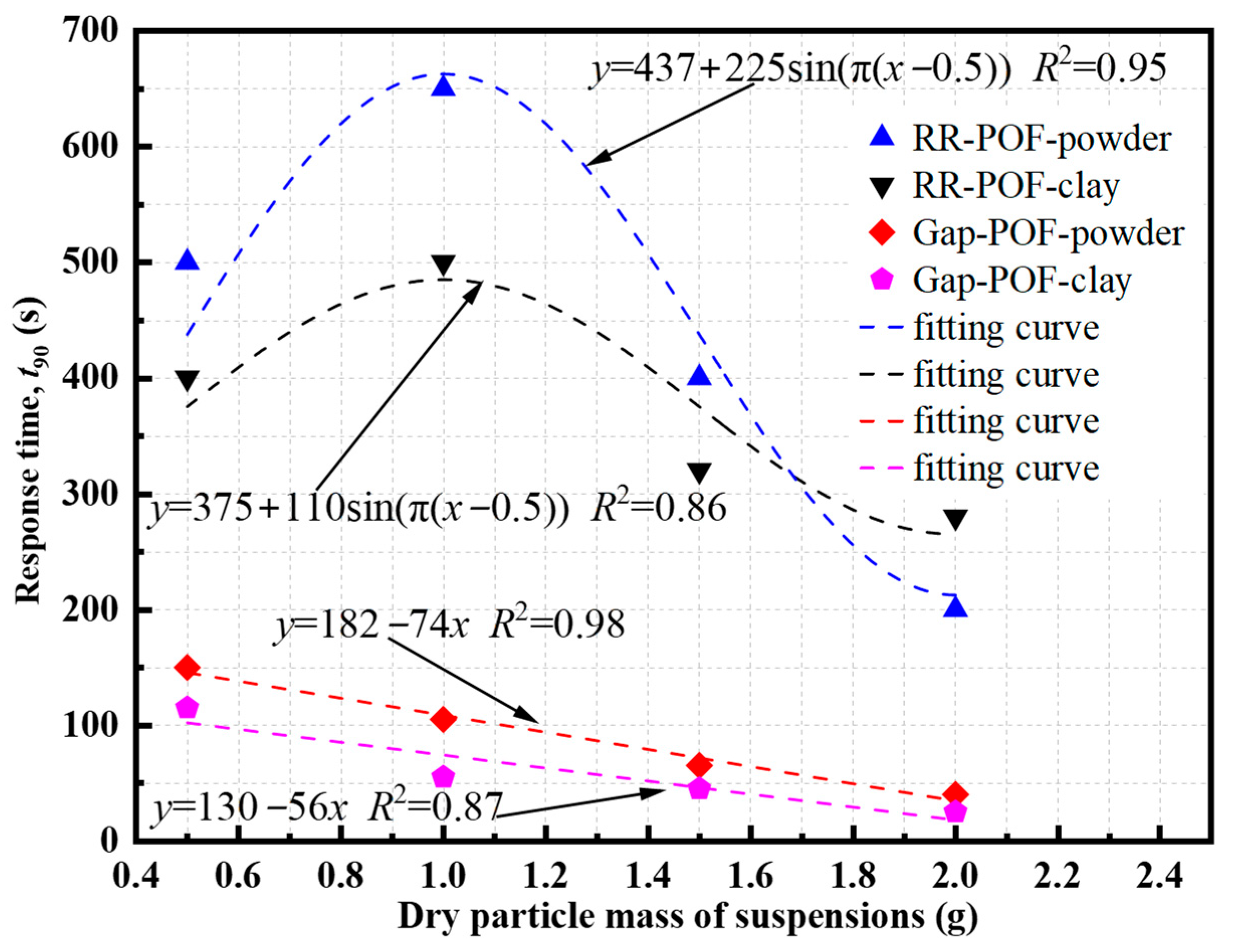

3.3. Response Time and Sensitivity Analysis of POF Sensors Under Different Concentrations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Downing, J. Turbidity Monitoring Environmental Instrumentation and Analysis Handbook; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 511–546. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Mandal, H. Influence of wastewater PH on turbidity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Dev. 2014, 4, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer, M. The effect of aquatic vegetation on turbidity; how important are the filter feeders? Hydrobiologia 1999, 408, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, E.H.; Beltran, V.L.; Tomlinson, M.S. Composition of water and suspended sediment in streams of urbanized subtropical watersheds in Hawaii. Appl. Geochem. 2004, 19, 1011–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, W.; Xia, X.; Liu, C.; Min, J.; Zhang, W.; Crittenden, J.C. Interactions between nano/micro plastics and suspended sediment in water: Implications on aggregation and settling. Water Res. 2019, 161, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, S. Particulate composition and origin of suspended sediment in the R. Don, Aberdeenshire, UK. Sci. Total Environ. 2001, 265, 281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Viers, J.; Dupr’e, B.; Gaillardet, J. Chemical composition of suspended sediments in World Rivers: New insights from a new database. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 853–868. [Google Scholar]

- Wilber, D.H.; Clarke, D.G. Biological effects of suspended sediments: A review of suspended sediment impacts on fish and shellfish with relation to dredging activities in estuaries. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2001, 21, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, W.; Rubinstein, N.; Melzian, B.; Hill, B. The Biological Effects of Suspended and Bedded Sediment (SABS) in Aquatic Systems: A Review Internal Report; US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research & Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Skarbøvik, E.; Veen, S.G.M.V.; Lannergård, E.E.; Wenng, H.; Stutter, M.; Bieroza, M.; Atcheson, K.; Jordan, P.; Fölster, J.; Mellander, P.-E.; et al. Comparing in situ turbidity sensor measurements as a proxy for suspended sediments in north-western European streams. CATENA 2023, 225, 107006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, F.; Bisantino, T.; Corbino, R.; Milillo, F.; Romano, G.; Liuzzi, G.T. Monitoring and analysis of suspended sediment transport dynamics in the Carapelle torrent (southern Italy). CATENA 2010, 80, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.; Paule, M.C.; Lee, B.-Y.; Umer, R.; Sukhbaatar, C.; Lee, C.-H. Investigation of turbidity and suspended solids behavior in storm water run-off from different land-use sites in South Korea. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 53, 3088–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, D.E.; Shaffer, M.B.; Blackwell, J.D. Sediment Export from a Highway Construction Site in Central North Carolina. Trans. ASABE 2011, 54, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Fan, H.; Chen, X.; Mi, C. Estimating low eroded sediment concentrations by turbidity and spectral characteristics based on a laboratory experiment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Kuwano, R. Suffusion and clogging by one-dimensional seepage tests on cohesive soil. Soils Found. 2015, 55, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Kuwano, R. Laboratory testing for evaluation of the influence of a small degree of internal erosion on deformation and stiffness. Soils Found. 2018, 58, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, T.; Suzuki, M.; Komori, A. Suffusion behavior under fluctuated hydraulic gradient conditions focusing on the amount and size of soil particles contained in drainage. Soils Found. 2025, 65, 101600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Water Quality Determination of Turbidity Turbidimeter Method: HJ 1075-2019; China Environmental Publishing Group: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, T.; Lewis, M.; Chang, G. Optical oceanography: Recent advances and future directions using global remote sensing and in situ observations. Rev. Geophys. 2006, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Shen, W.; Wang, X. Applications of wireless sensor networks in marine environment monitoring: A survey. Sensors 2014, 14, 16932–16954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.S.; Kuan, W.; Fan, C.; Chen, C. Rainfall Threshold Assessment Corresponding to the Maximum Allowable Turbidity for Source Water. Water Environ. Res. 2016, 88, 2285–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, C.T.; Zahrani, A.A.; Duan, L.; Wu, T. A glass-fiber-optic turbidity sensor for real-time in situ water quality monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillett, D.; Marchiori, A. A low-cost continuous turbidity monitor. Sensors 2019, 19, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanga, R.; Sivaramakrishna, M.; Rao, G.P. Design and development of a quasi-digital sensor and instrument for water turbidity measurement. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2019, 30, 115106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhang, H.; Qian, J. Monitoring of early curing stage of cemented soil using polymer optical fiber sensors and microscopic observation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 436, 136888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; Tang, G.; Ma, X. Visualization of soil freezing phase transition and moisture migration using polymer optical fibers. Measurement 2024, 229, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Akutagawa, S.; Tomoshige, Y.; Kimura, T. Experimental Investigation for Monitoring Corrosion Using Plastic Optical Fiber sensors. Sensors 2024, 24, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akutagawa, S.; Machijima, Y. A new optical fiber sensor for reading RGB intensities of light returning from an observation point in geo-materials. In Proceedings of the 49th US Rock Mechanics/Geotechnical Symposium, San Francisco, CA, USA, 28 June–1 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akutagawa, S.; Machijima, Y.; Sato, T.; Takahashi, A. Experimental characterization of movement of water and air in graular material by using optic fiber sensor with an emphasis on refractive index of light. In Proceedings of the 51th US Rock Mechanics/Geotechnical Symposium, San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–28 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Particle Dry Weight (g) | Soil | Sensor Type | Response Direction | t90 (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | Silica powder | RR-POF | Increasing | 500 |

| 1.0 | Silica powder | RR-POF | Increasing | 650 |

| 1.5 | Silica powder | RR-POF | Increasing | 400 |

| 2.0 | Silica powder | RR-POF | Increasing | 200 |

| 0.5 | DL clay | RR-POF | Increasing | 400 |

| 1.0 | DL clay | RR-POF | Increasing | 500 |

| 1.5 | DL clay | RR-POF | Increasing | 320 |

| 2.0 | DL clay | RR-POF | Increasing | 280 |

| 0.5 | Silica powder | Gap-POF | Decreasing | 150 |

| 1.0 | Silica powder | Gap-POF | Decreasing | 105 |

| 1.5 | Silica powder | Gap-POF | Decreasing | 65 |

| 2.0 | Silica powder | Gap-POF | Decreasing | 40 |

| 0.5 | DL clay | Gap-POF | Decreasing | 115 |

| 1.0 | DL clay | Gap-POF | Decreasing | 55 |

| 1.5 | DL clay | Gap-POF | Decreasing | 45 |

| 2.0 | DL clay | Gap-POF | Decreasing | 25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Qian, J.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, H. Experimental Study on Dual-Structure Polymer Optical Fiber Sensors for Turbidity Detection. Sensors 2026, 26, 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020351

Zhang J, Liu Z, Li J, Qian J, Zhou B, Zhang H. Experimental Study on Dual-Structure Polymer Optical Fiber Sensors for Turbidity Detection. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):351. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020351

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jiafeng, Zhibin Liu, Junshi Li, Jiangu Qian, Bing Zhou, and Haihua Zhang. 2026. "Experimental Study on Dual-Structure Polymer Optical Fiber Sensors for Turbidity Detection" Sensors 26, no. 2: 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020351

APA StyleZhang, J., Liu, Z., Li, J., Qian, J., Zhou, B., & Zhang, H. (2026). Experimental Study on Dual-Structure Polymer Optical Fiber Sensors for Turbidity Detection. Sensors, 26(2), 351. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020351