A Five-Electrode Contactless Conductivity Detector Based on a Sandwiched Microfluidic Chip for Miniaturized Ion Chromatography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagent

2.2. Detection Principle

2.3. Detection Dell Microchip Design and Fabrication

2.4. Detection Circuit Design

2.5. Detector Assembly and Evaluation of Detector Performance

2.6. Detection After Chromatography Separation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of Conditions

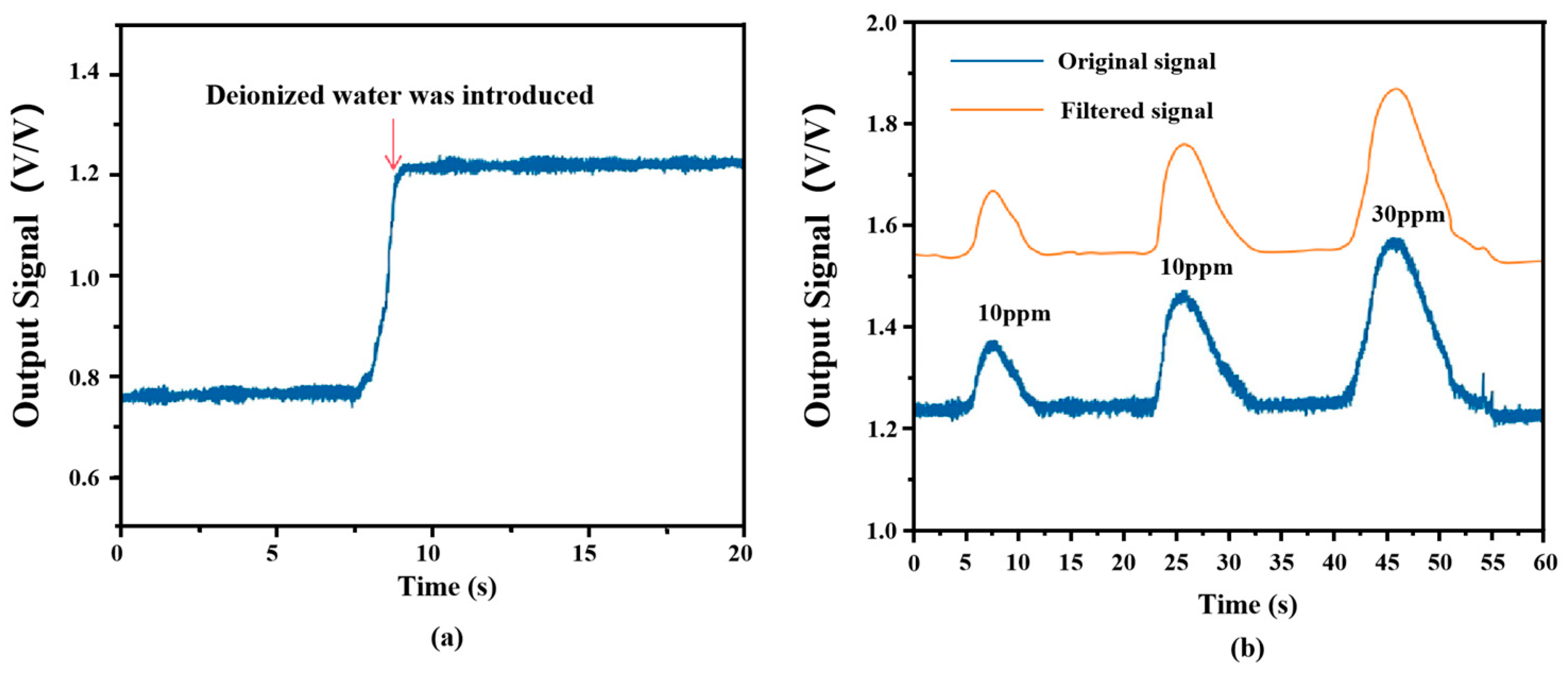

3.2. Baseline Noise and SNR Measurements

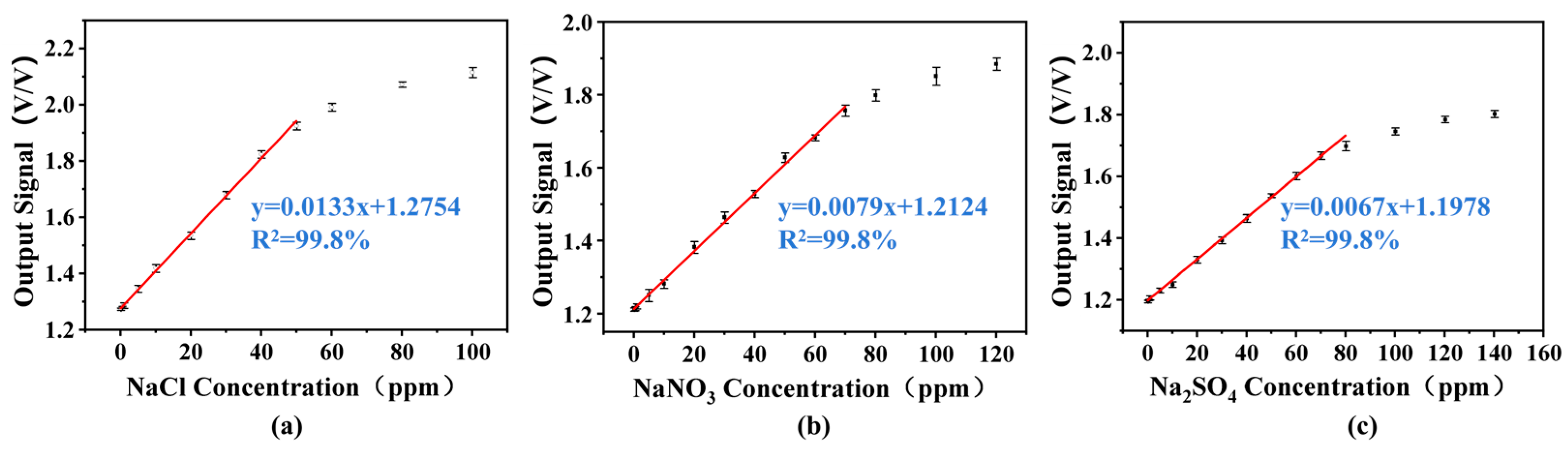

3.3. Linearity Measurements and LOD

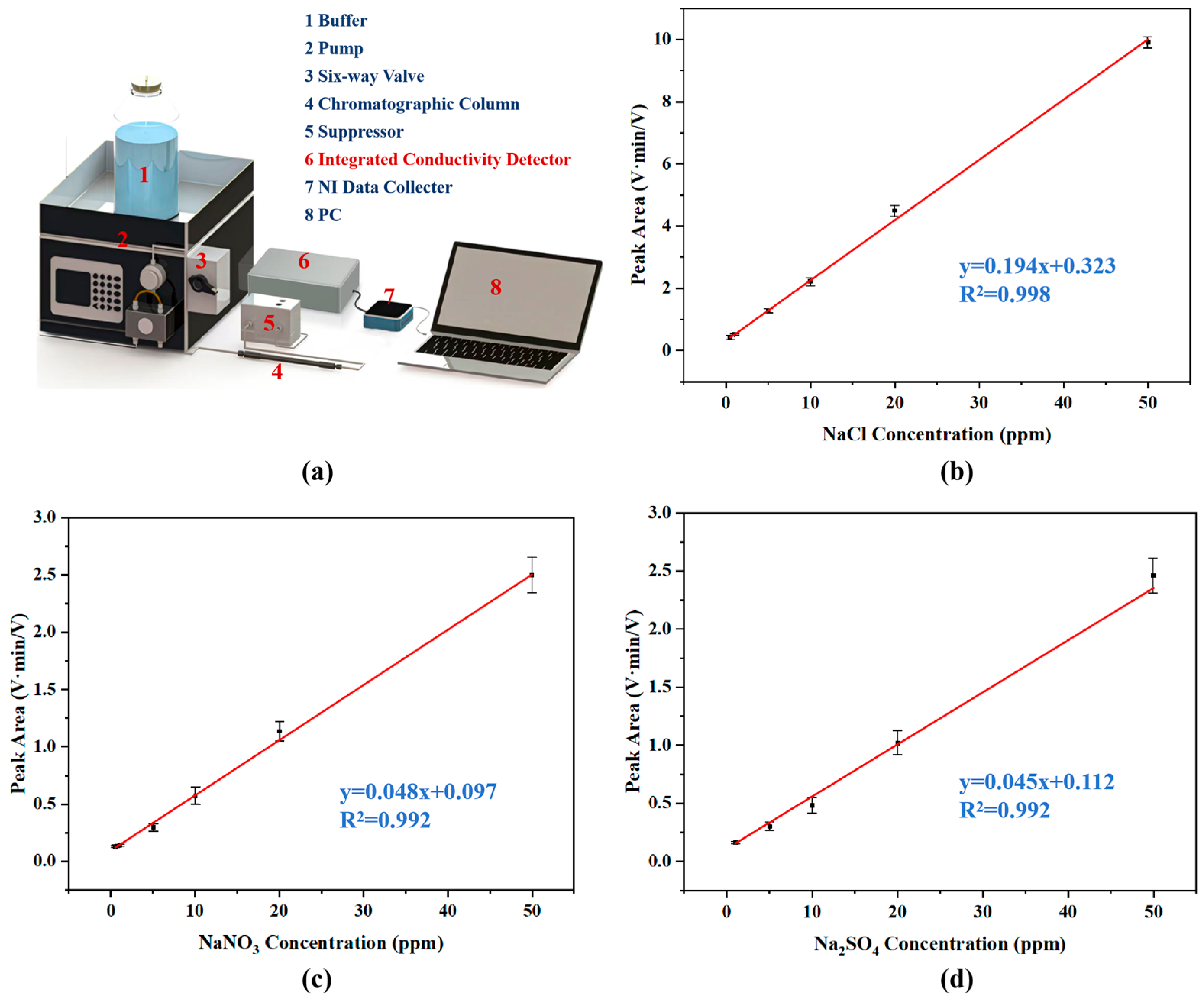

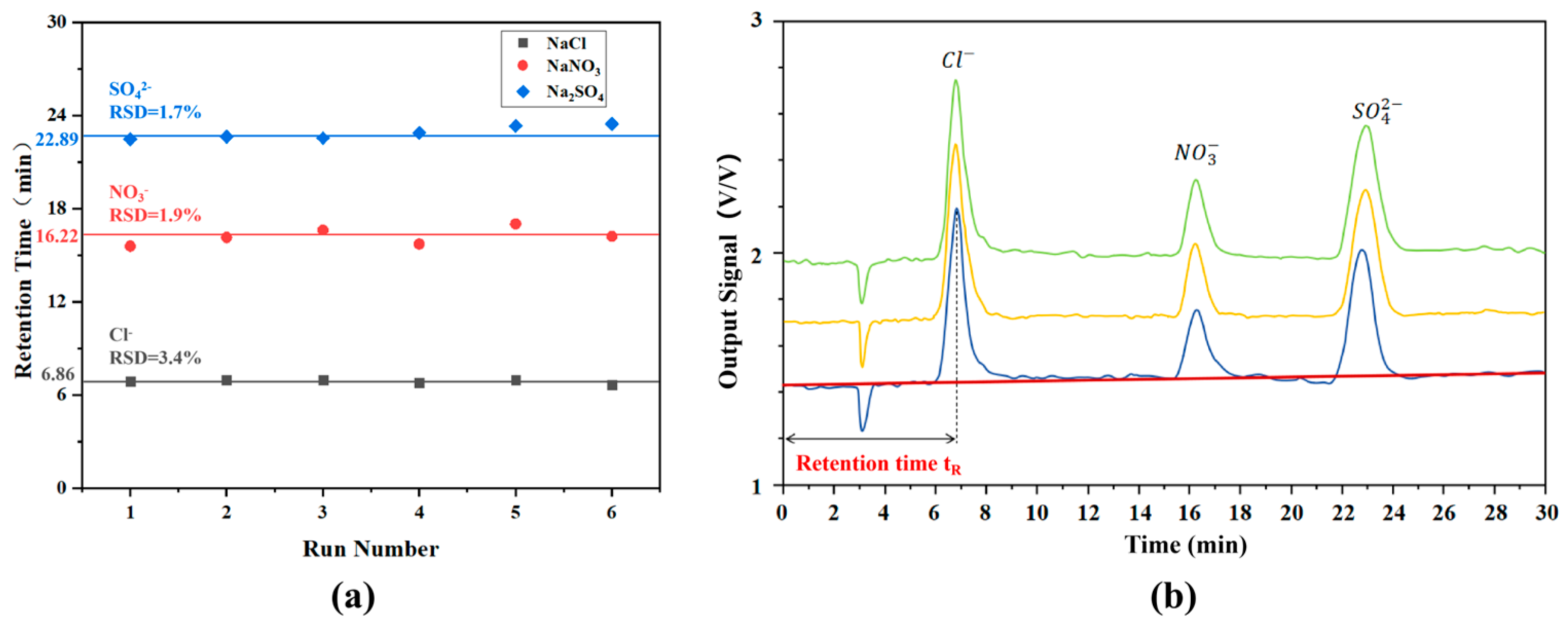

3.4. IC System Separation and Detection

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pang, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, W. Applications of Ion Chromatography in Urine Analysis: A Review. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1706, 464231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Rehman, I.U.; Devolder, D.; Eggerickx, A.; Van Schepdael, A.; Adams, E. Application of Ion Chromatography for Determination of Inorganic Ions and Sorbitol in Phosphate Syrup. Electrophoresis 2025, 24, 1717–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalski, R.; Kończyk, J. Ion Chromatography and Related Techniques in Carbohydrate Analysis: A Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schepdael, A. Capillary Electrophoresis as a Simple and Low-Cost Analytical Tool for Use in Money-Constrained Situations. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 160, 116992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, A.; Nishimura, T.; Koyama, K.; Maeki, M.; Tani, H.; Tokeshi, M. A Portable Liquid Chromatography System Based on a Separation/Detection Chip Module Consisting of a Replaceable Ultraviolet–Visible Absorbance or Contactless Conductivity Detection Unit. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1706, 464272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, D.; Zhang, R.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Ma, H.; Li, M.; Chang, H. Compact Photometric Detector Integrated with Separation Microchip for Potential Portable Liquid Chromatography System. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1731, 465175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemida, M.; Ghiasvand, A.; Macka, M.; Gupta, V.; Haddad, P.R.; Paull, B. Recent Advances in Miniaturization of Portable Liquid Chromatography with Emphasis on Detection. J. Sep. Sci. 2023, 46, 2300283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Zia-ul-Haq, M.; Ali, A.; Naeem, S.; Intisar, A.; Han, D. Ion Chromatography Coupled with Fluorescence/UV Detector: A Comprehensive Review of Its Applications in Pesticides and Pharmaceutical Drug Analysis. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, B. Recent Advances in Microchip Liquid Chromatography. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2021, 39, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marle, L.; Greenway, G.M. Microfluidic Devices for Environmental Monitoring. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2005, 24, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascolo, G.; Lopez, A.; Detomaso, A.; Lovecchio, G. Ion Chromatography–Electrospray Mass Spectrometry for the Identification of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids during 2,4-Dichlorophenol Degradation. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1067, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takekawa, V.S.; Marques, L.A.; Strubinger, E.; Segato, T.P.; Bogusz, S.; Brazaca, L.C.; Carrilho, E. Development of Low-Cost Planar Electrodes and Microfluidic Channels for Applications in Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detection (C4D). Electrophoresis 2021, 42, 1560–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tůma, P. Steady-State Microdialysis of Microliter Volumes of Body Fluids for Monitoring of Amino Acids by Capillary Electrophoresis with Contactless Conductivity Detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1287, 342113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavendish, H. The Electrical Researches; Maxwell, J.C., Ed.; The University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, J. Two Centuries of Quantitative Electrolytic Conductivity. Anal. Chem. 1984, 56, 561A–570A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, A.J.; Faulkner, L.R.; White, H.S. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kubáň, P.; Hauser, P. 20th Anniversary of Axial Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detection in Capillary Electrophoresis. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 102, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutter, J.P. Liquid Phase Chromatography on Microchips. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1221, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hou, Y.; Yang, B.; Liu, X.; Wu, J. Fabrication of Conventional Ion Chromatography–Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detector. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2018, 36, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltro, W.K.T.; Lima, R.S.; Segato, T.P.; Carrilho, E. Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detection on Microfluidic Systems—Ten Years of Development. Anal. Methods 2012, 4, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugere, F.; Guijt, R.; Bastemeijer, J.; van der Steen, G.; van Dedem, G. On-Chip Contactless Four-Electrode Conductivity Detection for Capillary Electrophoresis Devices. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Xie, B.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X. A Five-Electrode Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detector with a Low Limit of Detection. Anal. Methods 2023, 15, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chang, H. Chip-Based Ion Chromatography with a Sensitive Five-Electrode Conductivity Detector for the Simultaneous Detection of Multiple Ions in Drinking Water. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2020, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, B.; Coelho, A.; Beauchamp, M.J.; do Lago, C.L.; Kubáň, P. 3D-Printed Microchip Electrophoresis Device Containing Spiral Electrodes for Integrated Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govinda, R.; Salyards, P.; McCoy, C.; Cable, M.; Stillman, D. Polymer-Based Contactless Conductivity Detector for Europan Salts (PolyCoDES). Sensors 2025, 25, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J. An Improved Dual-Channel Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detector with High Detection Performance. Analyst 2022, 147, 2106–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z. Determination of Nanoplastics Using a Novel Contactless Conductivity Detector with Controllable Geometric Parameters. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Wang, L.; Su, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. A Novel Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detection Microfluidic Chip Integrated with 3D Microelectrodes for On-Site Determination of Soil Nutrients. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 219, 108829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, F.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J.; Fang, Z. A Polydimethylsiloxane Electrophoresis Microchip with a Thickness-Controllable Insulating Layer for Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detection. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 25, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltussen, E.; Guijt, R.; Steen, G.; Lammertink, R.; van Dedem, G. Considerations on Contactless Conductivity Detection in Capillary Electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2002, 23, 2888–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. Silicon Electro-Optic Micro-Modulator Fabricated in Standard CMOS Technology as Components for All-Silicon Monolithic Integrated Optoelectronic Systems. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2021, 31, 054001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tůma, P.; Samcová, E.; Štulík, K. Contactless Conductivity Detection in Capillary Electrophoresis Employing Capillaries with Very Low Inner Diameters. Electroanalysis 2011, 23, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. The Noteworthy Chloride Ions in Reclaimed Water: Harmful Effects, Concentration Levels and Control Strategies. Water Res. 2022, 215, 118271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Chauhan, R.; Kale, S.; Patil, S. Groundwater Nitrate Contamination and Its Effect on Human Health: A Review. Water Conserv. Sci. Eng. 2025, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Qu, S.; Ren, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H. Understanding the Global Distribution of Groundwater Sulfate and Assessing Population at Risk. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21002–21014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyanyiwa, J.; Hauser, P.C. High-Voltage Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detection for Microchip Capillary Electrophoresis. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 6378–6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Plistil, A.; Simpson, R.; Breadmore, M.C. Instrumentation for Hand-Portable Liquid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1327, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; He, W.; Zhang, L.; Chang, H. A Novel Planar Grounded Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity Detector for Microchip Electrophoresis. Micromachines 2022, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koczka, P.; Bodoki, E.; Gáspár, A. Application of Capacitively Coupled Contactless Conductivity as an External Detector for Zone Electrophoresis in Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Chips. Electrophoresis 2016, 37, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudry, A.; Nai, Y.; Guijt, R.; Breadmore, M.C. Polymeric Microchip for the Simultaneous Determination of Anions and Cations by Hydrodynamic Injection Using a Dual-Channel Sequential Injection Microchip Electrophoresis System. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 3380–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breadmore, M.C. Capillary and Microchip Electrophoresis: Challenging the Common Conceptions. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1221, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, Z.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y. Research on Interference and Suppression of Electronic Drift Electric Field Sensor. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications (ICIEA), Xi’an, China, 19–21 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Detector | Detection Limit (LOD) | References |

|---|---|---|

| PG-C4D | 50–100 μM | [38] |

| PDMS chip-C4D | 3.66–14.7 μM | [39] |

| Five-Electrode C4D | 10–13 μM | This work |

| Ions | Concentration (ppm) | 0.5 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cl− | Average Peak Area (V·min/V) | 0.42 | 0.52 | 1.29 | 2.24 | 4.49 | 9.92 |

| Average Retention Time (min) | 6.58 | 6.69 | 6.88 | 6.79 | 6.91 | 6.65 | |

| NO3− | Average Peak Area (V·min/V) | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.59 | 1.12 | 2.48 |

| Average Retention Time (min) | 15.50 | 16.35 | 16.84 | 16.62 | 17.15 | 16.57 | |

| SO42− | Average Peak Area (V·min/V) | - | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 1.03 | 2.55 |

| Average Retention Time (min) | - | 22.08 | 22.55 | 22.89 | 22.33 | 23.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, K.; Zhang, R.; Wang, M.; Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H. A Five-Electrode Contactless Conductivity Detector Based on a Sandwiched Microfluidic Chip for Miniaturized Ion Chromatography. Sensors 2026, 26, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010089

Chen K, Zhang R, Wang M, Wang B, Wang S, Zhao H. A Five-Electrode Contactless Conductivity Detector Based on a Sandwiched Microfluidic Chip for Miniaturized Ion Chromatography. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Kai, Ruirong Zhang, Mengbo Wang, Bo Wang, Shaoshuai Wang, and Haitao Zhao. 2026. "A Five-Electrode Contactless Conductivity Detector Based on a Sandwiched Microfluidic Chip for Miniaturized Ion Chromatography" Sensors 26, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010089

APA StyleChen, K., Zhang, R., Wang, M., Wang, B., Wang, S., & Zhao, H. (2026). A Five-Electrode Contactless Conductivity Detector Based on a Sandwiched Microfluidic Chip for Miniaturized Ion Chromatography. Sensors, 26(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010089