Event-Based Vision Application on Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: A Systematic Review of Prospects and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

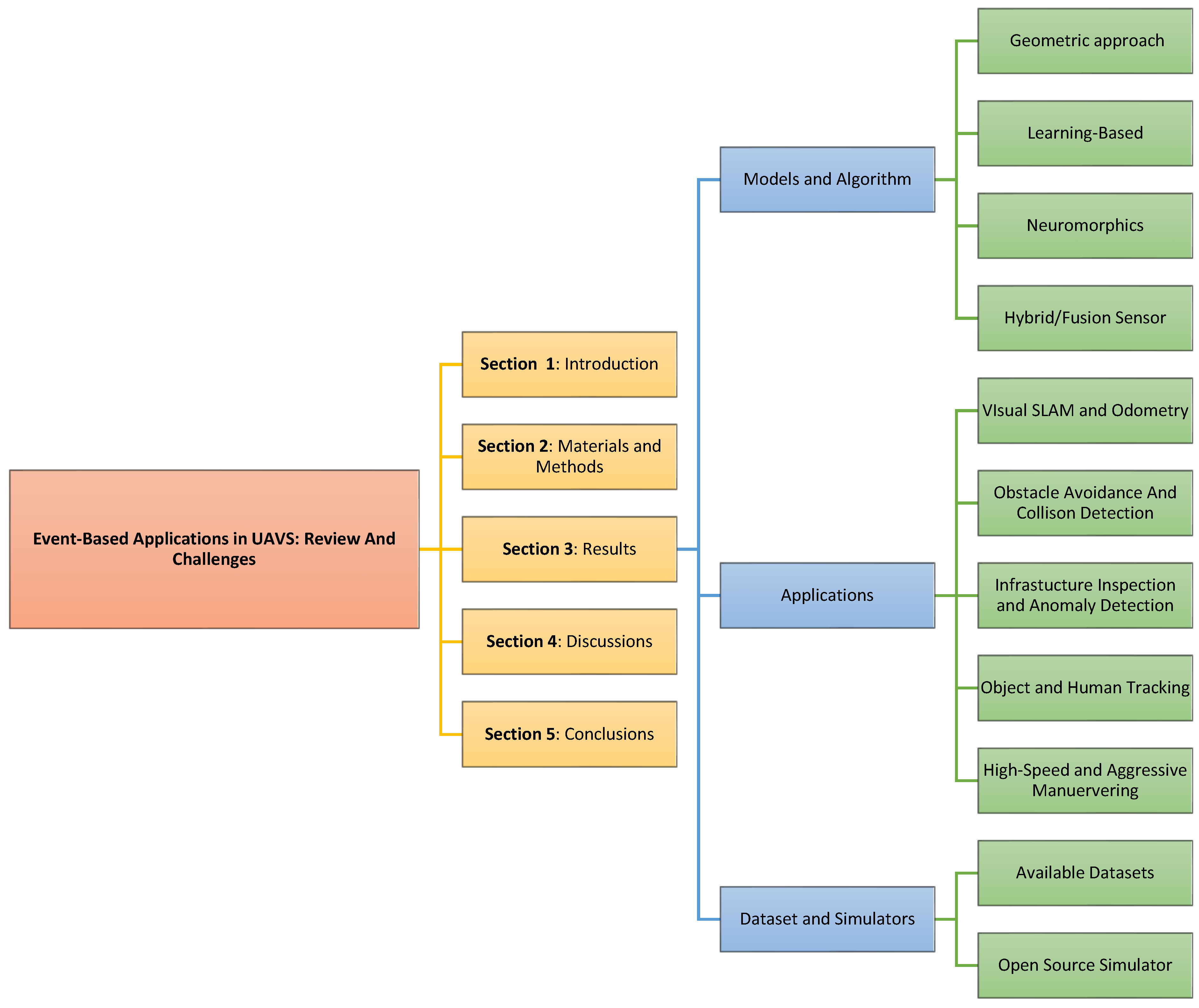

1.1. Background of the Study

- (i)

- To examine existing algorithms and techniques spanning geometric approaches, learning-based approaches, neuromorphic computing, and hybrid strategies for processing event data in UAV settings. Understanding how these algorithms outperform or fall short compared to traditional vision pipelines is central to validating the potential of event cameras.

- (ii)

- To explore the diverse real-world applications of event cameras in UAVs, such as obstacle avoidance, SLAM, object tracking, infrastructure inspection, and GPS-denied navigation. This review highlights both the demonstrated benefits and operational challenges faced in field deployment.

- (iii)

- To catalog and critically assess publicly available event camera datasets relevant to UAVs, including their quality, scope, and existing limitations. A well-curated dataset is foundational for algorithm development and benchmarking.

- (iv)

- Identify and evaluate open-source simulation tools that support event camera modeling and their integration into UAV environments. Simulators play a vital role in reducing experimental costs and enabling reproducible research.

- (v)

- To project the future potential of event cameras in UAV systems, including the feasibility of replacing standard cameras entirely, emerging research trends, hardware innovations, and prospective areas for interdisciplinary collaboration.

1.2. Basic Principles of an Event Camera

1.3. Types of Event Cameras

2. Materials and Methods

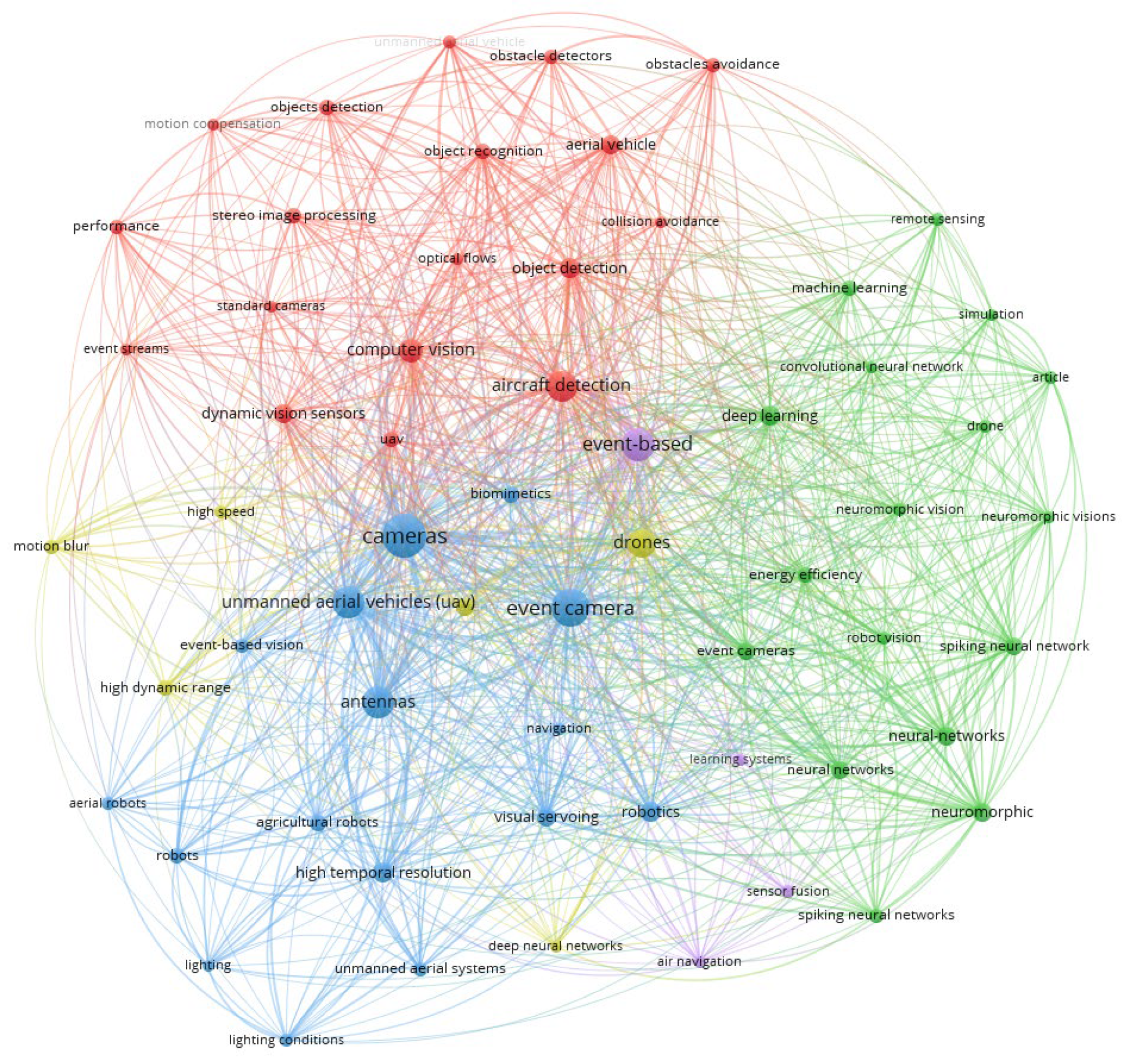

2.1. Search Terms

2.2. Search Strategy and Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria: Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference proceedings that directly applied event cameras in UAV contexts, with empirical evaluation of systems, algorithms, or datasets related to UAV navigation, perception, tracking, SLAM, or object recognition.

- Exclusion Criteria: Publications prior to 2015, non-English studies, duplicate publications, secondary summaries, and research focusing solely on hardware design or biological vision systems without any application to UAV robotics.

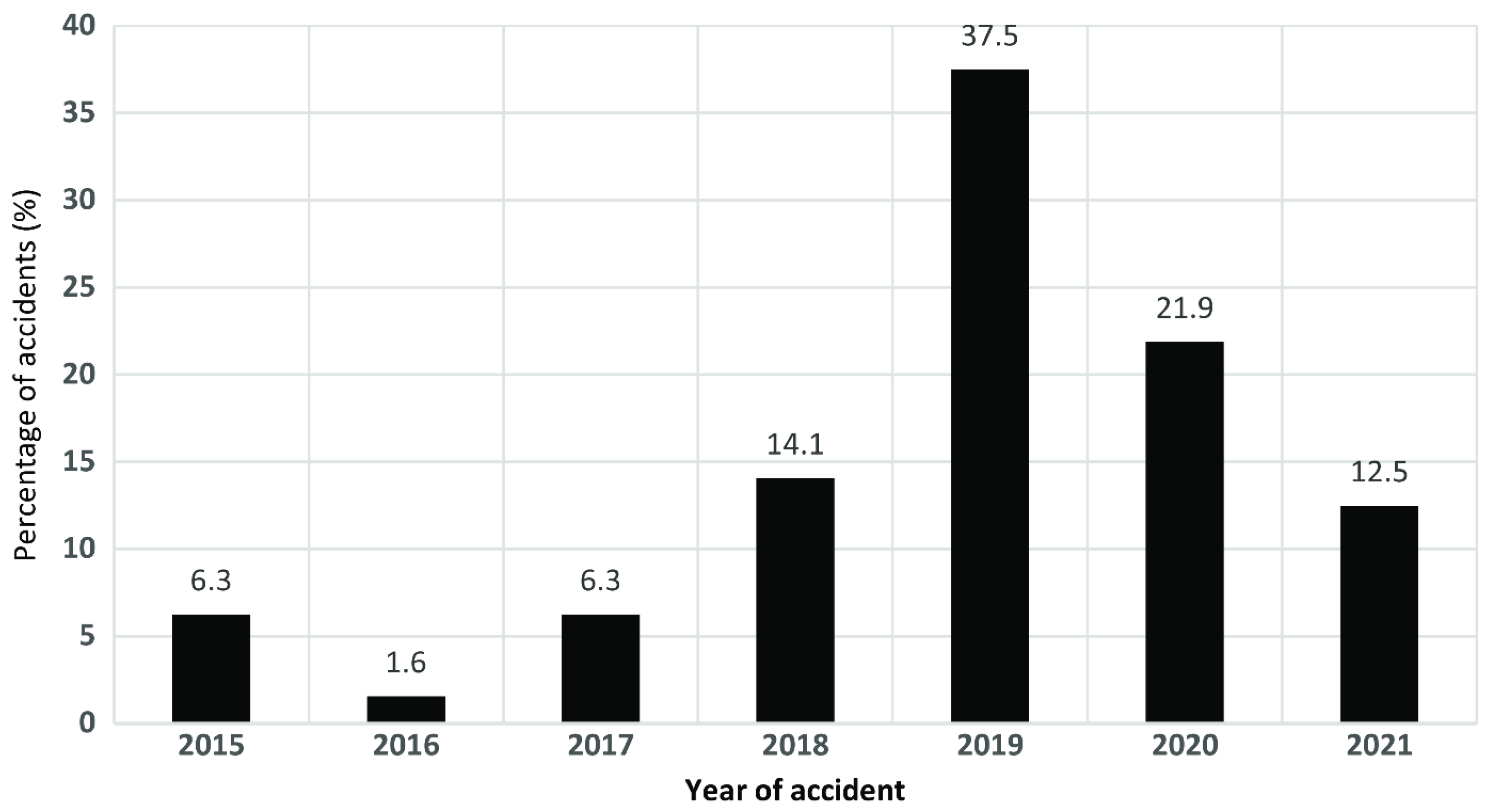

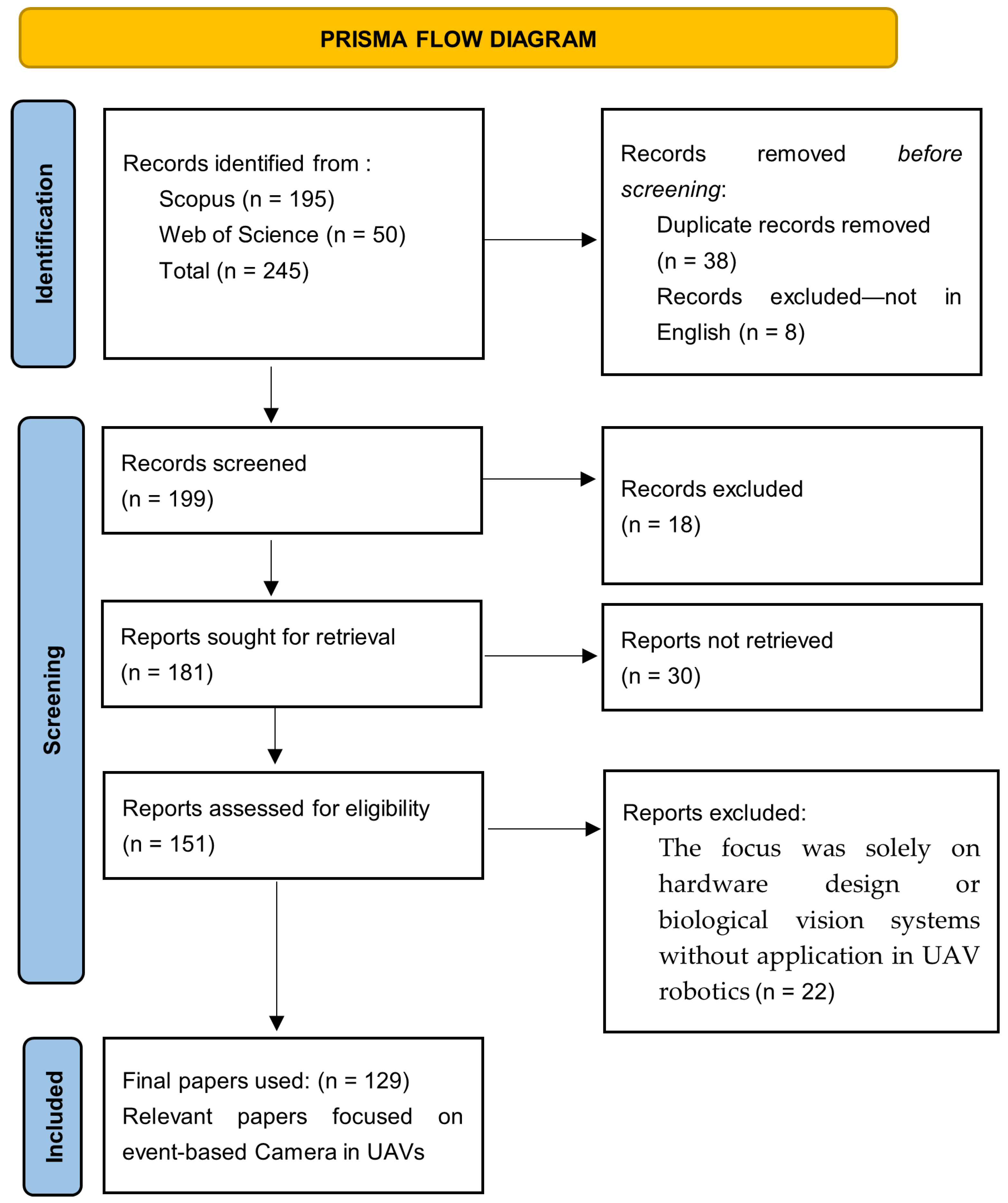

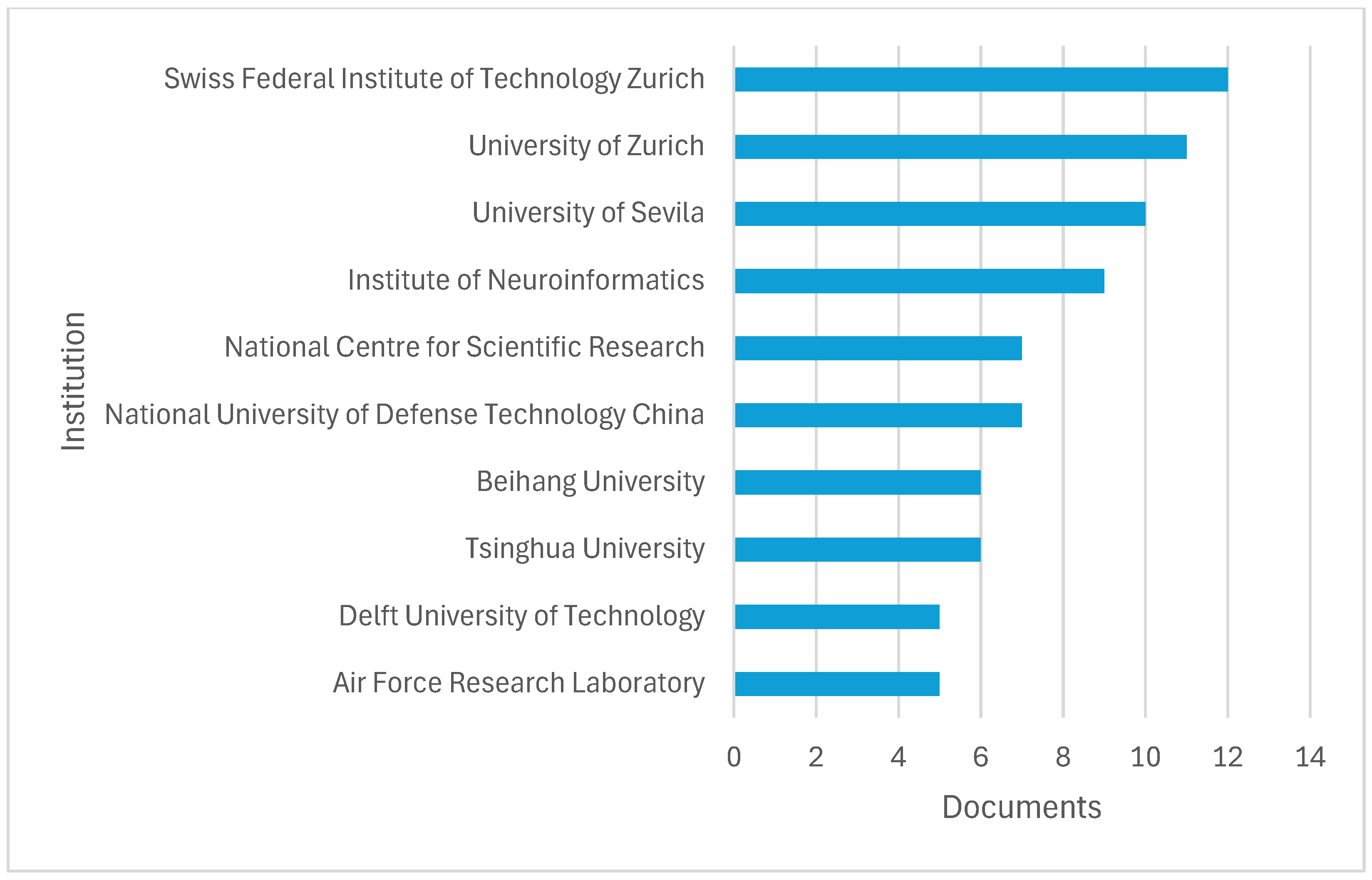

- Identification: An initial total of 245 records were identified from Scopus (n = 195) and Web of Science (n = 50)

- Removal of Redundancies: Duplicate records (n = 38) and non-English records (n = 8) were removed.

- Screening: The remaining 199 records were screened based on titles and abstracts. This screening phase excluded 18 records.

- Retrieval and Eligibility Assessment: Reports sought for retrieval totaled 181, with 30 not retrieved. The remaining 151 reports were assessed for eligibility. During this assessment, 22 reports were excluded because their focus was solely on hardware design or biological vision systems without applications in UAV robotics.

- Final Selection: A total of 129 relevant papers were ultimately included in the review. These selection processes are indicated in Table 2.

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Review of Past Survey of Event Cameras in UAV Applications

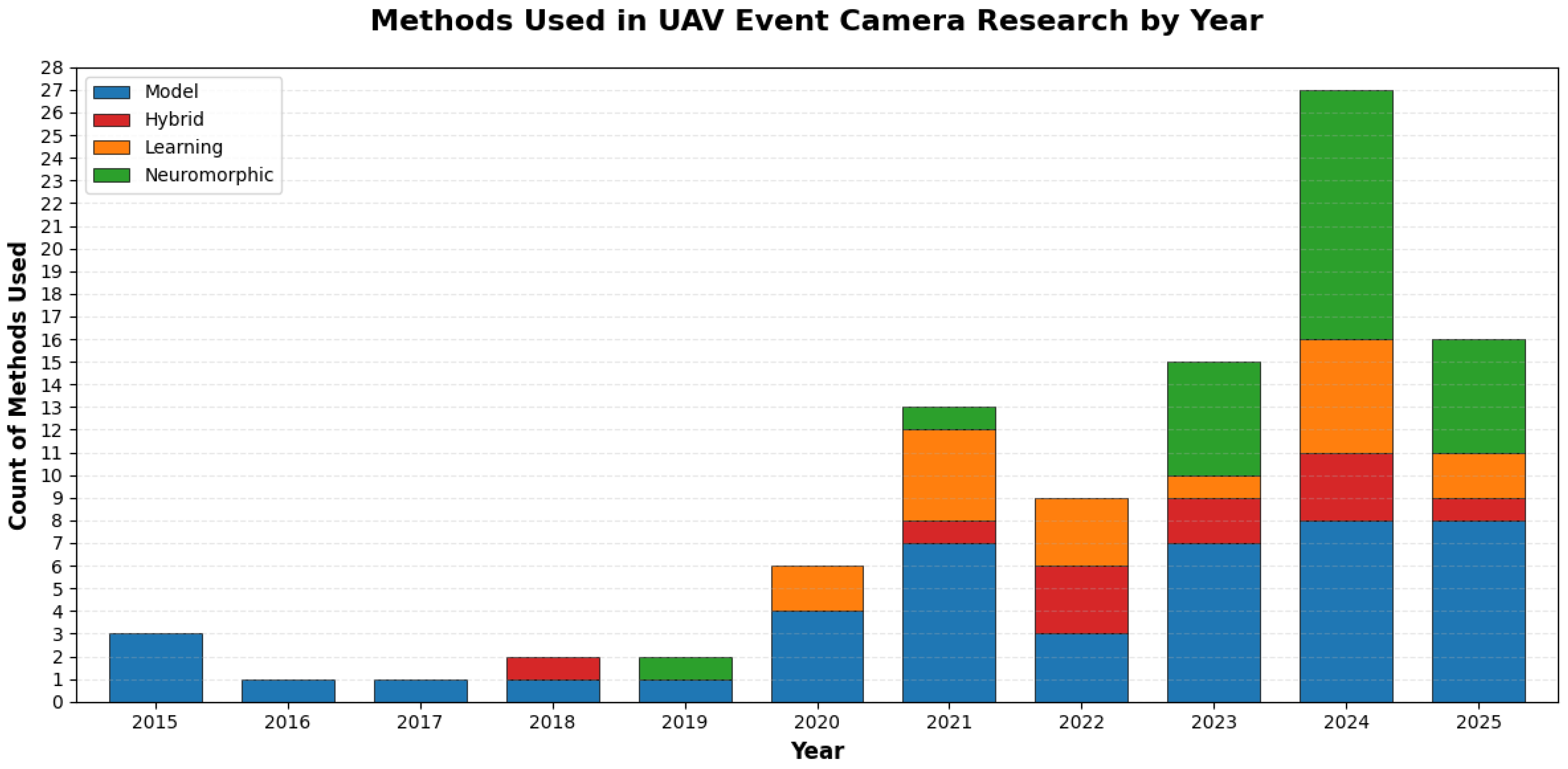

3.2. Models and Algorithms

3.2.1. Geometric Approach

3.2.2. Learning-Based Methods

3.2.3. Neuromorphic Computing Approach

3.2.4. Hybrid Sensor Integration Methods

3.3. Application Benefits of Event Camera Vision Systems in UAVs

3.3.1. Visual SLAM and Odometry

3.3.2. Obstacle Avoidance and Collison Detection

3.3.3. GPS-Denied Navigation and Terrain Relative Flight

3.3.4. Infrastructure Inspection and Anomaly Detection

3.3.5. Object and Human Tracking in Dynamic Scenes

3.3.6. High-Speed and Aggressive Maneurvering

3.4. Datasets and Open-Source Tools

3.4.1. Available Datasets for Event Cameras in UAVs Applications

- A.

- Event Camera Dataset for High-Speed Robotic TasksThis dataset includes high-speed dynamic scenes that are relevant to UAV maneuvers, like fast-paced tracking and navigation tasks. It provides ground truth measurements from motion capture systems along with event data, which makes it useful for benchmarking high-speed perception algorithms in UAVs [29]. They indicated that there are two recent datasets that also utilize DAVISs: [100,101]. The first study is designed for comparing algorithms that estimate optical flow based on events [100]. This dataset includes both synthetic and real examples featuring pure rotational motion (three degrees of freedom) within simple scenes that have strong visual contrasts, and the ground truth information was obtained using an inertial measurement unit. However, the duration of the recording of this dataset is not sufficient for a reliable assessment of SLAM algorithm performance [102].

- B.

- Davis Drone Racing DatasetThis is the first drone racing dataset, and it contains synchronized inertia measuring units, standard camera images, event camera data, and precise ground truth poses recorded in indoor and outdoor environments [103]. The event camera used for this dataset is miniDAVIS346 with a special resolution of 346 × 260 pixels, which proved to be of better quality than the one used by [29], which is DAVIS240C, with a resolution of 240 by 180 pixels.

- C.

- Extreme Event Dataset (EED)This dataset was collected using the DAVIS246B bio-inspired sensor across two scenarios. It was mounted on a quadrotor and on handheld devices for non-rigid camera movement [1]. This is the first event camera dataset that is specifically designed for moving object detection and was used as a benchmark dataset by [104] in their segmentation method to split a scene into independent moving objects.

- D.

- Multi-Vehicle Stereo Event Camera Dataset (MVSEC)MVSEC provides event data captured in a diverse set of environments, including indoor and outdoor scenes. It includes stereo event cameras mounted on a UAV, synchronized with other sensors like IMUs and standard cameras. The dataset is crucial for stereo depth estimation, visual odometry, and SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) in UAVs [105]. This dataset was combined with the accuracy of the frame-based camera for high-speed optical flow estimation for UAV navigation with a validation of 19% error degradation sped up by 4x [98].

- E.

- RPG Group Zurich Event Camera DatasetThe research team at the University of Zurich is the leading force in advancing research on event-based cameras. These datasets were generated from their iniLabs using the DAVIS240C sensor. They were generated for different motions and scenes and contain events, images, IMU measurements, and camera calibrations. The output is available in text files and ROSbag binary files, which are compatible with Robot Operating System (ROS). This dataset is a standard for the development and assessment of algorithms in pose estimation, visual odometry [89], and SLAM [39], especially within UAV applications, but its dataset scenarios may not cover real-world UAV environments, potentially constraining generalizability [29].

- F.

- EVDodgeNet DatasetThis dataset called the Moving Object Dataset (MOD) was created using synthetic scenes for generating “unlimited” amount of training data with one or more dynamic objects in the scene [23]. This is the first dataset to focus on event-based obstacle avoidance and was specifically generated for neural network training.

- G.

- Event-Based Vision Dataset (EV-IMO)The most well-known dataset created especially for event cameras integrated into UAV systems is the Event-Based Vision Dataset (EV-IMO). It has dynamic scenes with a variety of moving objects that mimic UAV flight situations. According to [51], this dataset is especially helpful for problems involving object tracking, motion prediction, and feature extraction from event-based data.

- H.

- DSECThis dataset is similar to MVSEC since it was obtained from a monochrome camera and LIDAR sensor for ground truth. However, the data from these two Prophese Gen 3.1 sensor event cameras has a resolution that is three times higher than from MVSEC [106].

- I.

- EVIMO2This dataset expanded on EV-IMO with improved temporal synchronization between sensors and enhanced depth ground truth accuracy. Using Prophesee Gen3 cameras (640 × 480 pixels), it supported more complex perception tasks including optical flow and structure from motion [107].

3.4.2. Simulators and Emulators

- A

- Robotic Operating System (ROS)When creating UAVs equipped with event cameras, the Robotic Operating System (ROS) is frequently utilized. ROS offers an adaptable structure for combining sensors, handling information, and managing unmanned aerial vehicles. Event cameras require an event-driven architecture, which is supported with packages that make real-time processing and data fusion easier. Because ROS provides a wide range of libraries and tools for managing sensor data, path planning, and control algorithms, it is very beneficial. Rapid prototyping and testing are made possible by the collaborative development environment that ROS’s open-source nature supports [110].

- B

- Gazebo and RvizThe popular simulation and visualization tools Gazebo and Rviz are utilized with ROS for UAV development. With Gazebo, UAVs may be tested in virtual environments with dynamic objects and changing lighting, an essential feature for event cameras. Gazebo is a 3D simulation environment. Rviz, on the other hand, makes it simpler to debug and improve algorithms by providing real-time visualization of sensor data and the UAV’s condition as it was used by [88]. In Table 9 is the list of open-source event camera simulators and source codes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Replacing Frame-Based Camera with Event Camera in UAV Applications

4.2. Challenges in Software Development and Deployment for Event Camera Vision Systems in UAVs

4.3. Evolution of Event Camera Dataset for UAV Applications

4.4. Comparing the Algorithm

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APS | Active Pixel Sensor |

| ATIS | Asynchronous Time-Based Image Sensor |

| AirSIM | Aerial Information and Robotics Simulation |

| CEF | Chiasm-Inspired Event Filtering |

| CNN | Convolution Neural Network |

| D2QN | Deep Double Q-Network |

| DAVIS | Dynamic and Active-Pixel Vision Sensor |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DOF | Degree Of Freedom |

| DVS | Dynamic Vision Sensor |

| EED | Extreme Event Dataset |

| ESIM | Event Camera Simulator |

| EVO | Event-Based Visual Inertia Odometry |

| GPS | Global Position System |

| GTNN | Graph Transformer Neural Network |

| HDR | High Dynamic Range |

| IMU | Inertia Measuring Unit |

| LGMD | Locus Lobular Giant Movement Detector |

| LIDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| MEMS | Micromechanical System |

| MOD | Moving Object Detection |

| MVSEC | Multi-Vehicle Stereo Event Camera |

| PID | Proportional Integral Derivative |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue |

| ROS | Robotics Operating System |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| SNN | Spiking Neural Network |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UAS | Unmanned Aircraft System |

| VIO | Visual Inertia Odometry |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Mitrokhin, A.; Fermüller, C.; Parameshwara, C.; Aloimonos, Y. Event-based moving object detection and tracking. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Brandli, C.; Berner, R.; Yang, M.; Liu, S.-C.; Delbruck, T. A 240 × 180 130 db 3 µs latency global shutter spatiotemporal vision sensor. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 2014, 49, 2333–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, D.; Loquercio, A.; Derpanis, K.G.; Scaramuzza, D. End-to-end learning of representations for asynchronous event-based data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 5633–5643. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Kumar, S. A comprehensive insight into unmanned aerial vehicles: History, classification, architecture, navigation, applications, challenges, and future trends. Aerospace 2025, 12, 45–78. [Google Scholar]

- Outay, F.; Mengash, H.A.; Adnan, M. Applications of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) in road safety, traffic and highway infrastructure management: Recent advances and challenges. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 141, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwar, S.; Swarnkar, R.; Bhukya, S.; Namwade, G. Application of drone in agriculture. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 2500–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waharte, S.; Trigoni, N. Supporting search and rescue operations with UAVs. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Emerging Security Technologies, Canterbury, UK, 6–7 September 2010; pp. 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.; Kim, H. Analysis of amazon prime air uav delivery service. J. Knowl. Inf. Technol. Syst. 2017, 12, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Bi, L.; Liu, H.; Lou, H. Un-yolov5s: A uav-based aerial photography detection algorithm. Sensors 2023, 23, 5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.F.; Montes, G.A.; Puig, E.; Johnson, S.; Mengersen, K.; Gaston, K.J. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and artificial intelligence revolutionizing wildlife monitoring and conservation. Sensors 2016, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Jeong, Y.; Park, S.; Ryu, K.; Oh, G. A survey of drone use for entertainment and AVR (augmented and virtual reality). In Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality: Empowering Human, Place and Business; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 339–352. [Google Scholar]

- El Safany, R.; Bromfield, M.A. A human factors accident analysis framework for UAV loss of control in flight. Aeronaut. J. 2025, 129, 1723–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzhat, T.; Machida, F.; Andrade, E. Weather Impact Analysis for UAV-based Deforestation Monitoring Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 55th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks Workshops (DSN-W), Knoxville, TN, USA, 23–26 June 2025; pp. 224–230. [Google Scholar]

- De Mey, A. Event Cameras—An Evolution in Visual Data Capture. Available online: https://robohub.org/event-cameras-an-evolution-in-visual-data-capture (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Shariff, W.; Dilmaghani, M.S.; Kielty, P.; Moustafa, M.; Lemley, J.; Corcoran, P. Event cameras in automotive sensing: A review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 51275–51306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthi, B.; Verma, A.A.; Daniilidis, K.; Fermuller, C.; Yang, Y. Recent event camera innovations: A survey. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 342–376. [Google Scholar]

- Iddrisu, K.; Shariff, W.; Corcoran, P.; O’Connor, N.E.; Lemley, J.; Little, S. Event camera-based eye motion analysis: A survey. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 136783–136804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, D.; Scaramuzza, D. Low-latency automotive vision with event cameras. Nature 2024, 629, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune Business Insights. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle [UAV] Market Size, Share, Trends & Industry Analysis, By Type (Fixed Wing, Rotary Wing, Hybrid), By End-use Industry, By System, By Range, By Class, By Mode of Operation, and Regional Forecast, 2024–2032. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/industry-reports/unmanned-aerial-vehicle-uav-market-101603 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Li, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Ni, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, Z. Uav-human: A large benchmark for human behavior understanding with unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 16266–16275. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, G.; Delbrück, T.; Orchard, G.; Bartolozzi, C.; Taba, B.; Censi, A.; Leutenegger, S.; Davison, A.J.; Conradt, J.; Daniilidis, K.; et al. Event-based vision: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 44, 154–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, D.; Kleber, K.; Scaramuzza, D. Dynamic obstacle avoidance for quadrotors with event cameras. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eaaz9712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanket, N.J.; Parameshwara, C.M.; Singh, C.D.; Kuruttukulam, A.V.; Fermuller, C.; Scaramuzza, D.; Aloimonos, Y. Evdodgenet: Deep dynamic obstacle dodging with event cameras. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 10651–10657. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Gómez, J.P.; Tapia, R.; Garcia, M.D.M.G.; Dios, J.R.M.-D.; Ollero, A. Free as a bird: Event-based dynamic sense-and-avoid for ornithopter robot flight. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 5413–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzato, D.; Bono, F. An application-driven survey on event-based neuromorphic computer vision. Information 2024, 15, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenzin, S.; Rassau, A.; Chai, D. Application of event cameras and neuromorphic computing to VSLAM: A survey. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Xia, M.; Huang, Z.; Tian, L.; Zheng, X.; Chang, V.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H. Event-Based Pedestrian Detection Using Dynamic Vision Sensors. Electronics 2021, 10, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtsteiner, P.; Posch, C.; Delbruck, T. A 128 × 128 120 dB 15 μs latency asynchronous temporal contrast vision sensor. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 2008, 43, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueggler, E.; Rebecq, H.; Gallego, G.; Delbruck, T.; Scaramuzza, D. The event-camera dataset and simulator: Event-based data for pose estimation, visual odometry, and SLAM. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2017, 36, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, C.; Matolin, D.; Wohlgenannt, R. An asynchronous time-based image sensor. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Seattle, WA, USA, 18–21 May 2008; pp. 2130–2133. [Google Scholar]

- Joubert, D.; Marcireau, A.; Ralph, N.; Jolley, A.; Van Schaik, A.; Cohen, G. Event camera simulator improvements via characterized parameters. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 702765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Maier, G.; Flitter, M.; Gruna, R.; Längle, T.; Heizmann, M.; Beyerer, J. An extended modular processing pipeline for event-based vision in automatic visual inspection. Sensors 2021, 21, 6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeys, D.P.; Li, C.; Martel, J.N.; Bamford, S.; Longinotti, L.; Motsnyi, V.; Bello, D.S.S.; Delbruck, T. Color temporal contrast sensitivity in dynamic vision sensors. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Baltimore, MD, USA, 28–31 May 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerlinck, C.; Rebecq, H.; Stoffregen, T.; Barnes, N.; Mahony, R.; Scaramuzza, D. CED: Color event camera dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, E.A.; Flores-Fuentes, W.; Achakir, F.; Sergienko, O.; Murrieta-Rico, F.N. Vision-Based Navigation and Perception for Autonomous Robots: Sensors, SLAM, Control Strategies, and Cross-Domain Applications—A Review. Eng 2025, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Delbruck, T. Adaptive time-slice block-matching optical flow algorithm for dynamic vision sensors. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC), Newcastle, UK, 3–6 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, A.R.; Rebecq, H.; Horstschaefer, T.; Scaramuzza, D. Ultimate SLAM? Combining events, images, and IMU for robust visual SLAM in HDR and high-speed scenarios. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, G.; Rebecq, H.; Scaramuzza, D. A unifying contrast maximization framework for event cameras, with applications to motion, depth, and optical flow estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3867–3876. [Google Scholar]

- Mueggler, E.; Gallego, G.; Rebecq, H.; Scaramuzza, D. Continuous-time visual-inertial odometry for event cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 1425–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecq, H.; Horstschäfer, T.; Gallego, G.; Scaramuzza, D. Evo: A geometric approach to event-based 6-dof parallel tracking and mapping in real time. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2016, 2, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradt, J. On-Board Real-Time Optic-Flow for Miniature Event-Based Vision Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Zhuhai, China, 6–9 December 2015; pp. 1858–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, N.; Hardt, M.W.; Inalhan, G. Enabling UAVs night-time navigation through Mutual Information-based matching of event-generated images. In Proceedings of the AIAA/IEEE Digital Avionics Systems Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 1–5 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Li, Z.; Song, F. An Improved Asynchronous Corner Detection and Corner Event Tracker for Event Cameras. In Advances in Guidance, Navigation and Control; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, Volume 845; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhou, X.; Shuang, F. EAPTON: Event-based Antinoise Powerlines Tracking with ON/OFF Enhancement. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2774, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panetsos, F.; Karras, G.C.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Aerial Transportation of Cable-Suspended Loads with an Event Camera. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecq, H.; Ranftl, R.; Koltun, V.; Scaramuzza, D. Events-to-video: Bringing modern computer vision to event cameras. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 3857–3866. [Google Scholar]

- Maqueda, A.I.; Loquercio, A.; Gallego, G.; García, N.; Scaramuzza, D. Event-based vision meets deep learning on steering prediction for self-driving cars. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 5419–5427. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, A.Z.; Yuan, L.; Chaney, K.; Daniilidis, K. EV-FlowNet: Self-supervised optical flow estimation for event-based cameras. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.06898. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrokhin, A.; Ye, C.; Fermüller, C.; Aloimonos, Y.; Delbruck, T. EV-IMO: Motion segmentation dataset and learning pipeline for event cameras. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 3–8 November 2019; pp. 6105–6112. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, S.; Lv, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, M. MVT: Multi-Vision Transformer for Event-Based Small Target Detection. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, G. Event-Based Obstacle Sensing and Avoidance for an UAV Through Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Artificial Intelligence; Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 13606; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaboni, C.; Lobo, D.; Choi, J.-W.; Abichandani, P. Event-based motion capture system for online multi-quadrotor localization and tracking. Sensors 2022, 22, 3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, O.A.; Chehadeh, M.; Ayyad, A.; Wahbah, M.; Humais, M.A.; Boiko, I.; Seneviratne, L.; Zweiri, Y. Noise-Tolerant Identification and Tuning Approach Using Deep Neural Networks for Visual Servoing Applications. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 2276–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Tang, C.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, B.; Tian, Y.; Tang, J. Event Stream-Based Visual Object Tracking: A High-Resolution Benchmark Dataset and A Novel Baseline. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 19248–19257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkendi, Y.; Hay, O.A.; Humais, M.A.; Azzam, R.; Seneviratne, L.D.; Zweiri, Y.H. Dynamic-Obstacle Relative Localization Using Motion Segmentation with Event Cameras. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Chania, Greece, 4–7 June 2024; pp. 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Wu, B.; Zhou, H.; Zuo, H.; He, Z.; Xiao, C.; Fu, C. E3-Net: Event-Guided Edge-Enhancement Network for UAV-Based Crack Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM), Tokyo, Japan, 8–10 July 2024; pp. 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Deng, Y.J.; Xie, B.C.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.F. Neuromorphic event-based recognition boosted by motion-aware learning. Neurocomputing 2025, 630, 129678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, U.K.; Zanatta, L.; Fumagalli, M.; Cadena, C.; Tolu, S. Event-based classification of defects in civil infrastructures with artificial and spiking neural networks. In International Work-Conference on Artificial Neural Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 629–640. [Google Scholar]

- Hareb, D.; Martinet, J. EvSegSNN: Neuromorphic Semantic Segmentation for Event Data. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, J.; Tie, J.; Chen, R.; Xu, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Dai, H. A Fast and Safe Neuromorphic Approach for Obstacle Avoidance of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Kuching, Malaysia, 6–10 October 2024; pp. 1963–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes-Valles, F.; Hagenaars, J.J.; Dupeyroux, J.; Stroobants, S.; Xu, Y.; de Croon, G. Fully neuromorphic vision and control for autonomous drone flight. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eadi0591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salt, L.; Indiveri, G.; Sandamirskaya, Y. Obstacle avoidance with LGMD neuron: Towards a neuromorphic UAV implementation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Baltimore, MD, USA, 28–31 May 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, P.; Di Caterina, G.; Soraghan, J.; Andreopoulos, Y.; Matich, G. UAV Detection: A STDP Trained Deep Convolutional Spiking Neural Network Retina-Neuromorphic Approach. In Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning—ICANN 2019: Theoretical Neural Computation; Tetko, I.V., Karpov, P., Theis, F., Kurková, V., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagsted, R.K.; Vitale, A.; Binz, J.; Renner, A.; Larsen, L.B.; Sandamirskaya, Y. Towards neuromorphic control: A spiking neural network based PID controller for UAV. In Robotics: Science and Systems; Toussaint, M., Bicchi, A., Hermans, T., Eds.; MIT Press Journals: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.; Renner, A.; Nauer, C.; Scaramuzza, D.; Sandamirskaya, Y. Event-driven Vision and Control for UAVs on a Neuromorphic Chip. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanatta, L.; Di Mauro, A.; Barchi, F.; Bartolini, A.; Benini, L.; Acquaviva, A. Directly-trained spiking neural networks for deep reinforcement learning: Energy efficient implementation of event-based obstacle avoidance on a neuromorphic accelerator. Neurocomputing 2023, 562, 126885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, S.; Manna, R.K.; Roy, K. EV-Planner: Energy-Efficient Robot Navigation via Event-Based Physics-Guided Neuromorphic Planner. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 2080–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, A.; Ocket, I.; Bourdoux, A.; Sahli, H.; Catthoor, F.; Gielen, G.G.E. STDP-Driven Development of Attention-Based People Detection in Spiking Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2024, 16, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbour, D.A.R.; Cohen, K.; Harbour, S.D.; Ratliff, B.; Henderson, A.; Pennel, H.; Schlager, S.; Taha, T.M.; Yakopcic, C.; Asari, V.K.; et al. Martian Flight: Enabling Motion Estimation of NASA’s Next-Generation Mars Flying Drone by Implementing a Neuromorphic Event-Camera and Explainable Fuzzy Spiking Neural Network Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 AIAA DATC/IEEE 43rd Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–24 October 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- von Arnim, A.; Lecomte, J.; Borras, N.E.; Wozniak, S.; Pantazi, A. Dynamic event-based optical identification and communication. Front. Neurorobotics 2024, 18, 1290965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Ruan, H.; He, S.; Yang, T.; Guo, D. A biomimetic visual detection model: Event-driven LGMDs implemented with fractional spiking neuron circuits. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 71, 2978–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, H.; Liu, Y.; Shangguan, L. Taming Event Cameras With Bio-Inspired Architecture and Algorithm: A Case for Drone Obstacle Avoidance. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 4202–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shao, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J.; Cai, Z. REVIO: Range- and Event-Based Visual-Inertial Odometry for Bio-Inspired Sensors. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Li, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Q.; Xu, C.; Gao, F. FAST-Dynamic-Vision: Detection and Tracking Dynamic Objects with Event and Depth Sensing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 3071–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, D.; Xie, Y.; Cao, H.; Li, F.; Yang, Z. FlyTracker: Motion Tracking and Obstacle Detection for Drones Using Event Cameras. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM, New York, NY, USA, 17–20 May 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K.; Guo, H. Event-RGB Fusion for Insulator Defect Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th Asian Conference on Artificial Intelligence Technology (ACAIT), Fuzhou, China, 8–10 November 2024; pp. 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.Q.; Yu, X.H.; Luan, H.; Suo, J.L. Event-Assisted Object Tracking on High-Speed Drones in Harsh Illumination Environment. Drones 2024, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Chen, P.; Xie, Y.; Lu, P. PL-EVIO: Robust Monocular Event-Based Visual Inertial Odometry with Point and Line Features. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 6277–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.-H.; Raychowdhury, A. NeuroSLAM: A 65-nm 7.25-to-8.79-TOPS/W Mixed-Signal Oscillator-Based SLAM Accelerator for Edge Robotics. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 2021, 56, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, U.G.; Huo, X.; Zanatta, L.; Delbruck, T.; Cadena, C.; Fumagalli, M.; Tolu, S. Event-based Civil Infrastructure Visual Defect Detection: Ev-CIVIL Dataset and Benchmark. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.05679. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, S. Evtracker: An event-driven spatiotemporal method for dynamic object tracking. Sensors 2022, 22, 6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, A.; Verbelen, T.; Ocket, I.; Bourdoux, A.; Catthoor, F.; Gielen, G.G.E. Fail-Safe Human Detection for Drones Using a Multi-Modal Curriculum Learning Approach. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 7, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lele, A.S.; Fang, Y.; Anwar, A.; Raychowdhury, A. Bio-mimetic high-speed target localization with fused frame and event vision for edge application. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1010302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Rush, A.; Merkel, C.; Herrmann, E.; Jacob, A.P.; Thiem, C.; Jha, R. A neuromorphic SLAM architecture using gated-memristive synapses. Neurocomputing 2020, 381, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.J.; Xu, J.; Deng, K.; Lan, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhuge, X.; Yang, Z. TrinitySLAM: On-board Real-time Event-image Fusion SLAM System for Drones. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2024, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, A.; El-Rabbany, A.; Jacob, S. Event-based visual/inertial odometry for UAV indoor navigation. Sensors 2024, 25, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kueng, B.; Mueggler, E.; Gallego, G.; Scaramuzza, D. Low-latency visual odometry using event-based feature tracks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 9–14 October 2016; pp. 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Gallego, G.; Shen, S. Event-based stereo visual odometry. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1433–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tie, J.; Li, J.; Hu, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhao, J.; Wan, Z.; et al. Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Using Dynamic Vision Sensor. In Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning—ICANN 2023; Iliadis, L., Papaleonidas, A., Angelov, P., Jayne, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salt, L.; Howard, D.; Indiveri, G.; Sandamirskaya, Y. Parameter Optimization and Learning in a Spiking Neural Network for UAV Obstacle Avoidance Targeting Neuromorphic Processors. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 2020, 31, 3305–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueggler, E.; Baumli, N.; Fontana, F.; Scaramuzza, D. Towards evasive maneuvers with quadrotors using dynamic vision sensors. In Proceedings of the 2015 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR), Lincoln, UK, 2–4 September 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.H.; Li, Z.H.; Li, J.Y.; Lu, Y.C.; Kim, T.T.H. Event-frame object detection under dynamic background condition. J. Electron. Imaging 2024, 33, 043028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, D.; Arnab, R.; Parpart, G.; Kenyon, G.T.; Kim, E.; Watkins, Y. Event-To-Video Conversion for Overhead Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Southwest Symposium on Image Analysis and Interpretation, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 24–26 March 2024; pp. 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-K.; Wang, S.-E.; Wu, P.-H. Spike-event object detection for neuromorphic vision. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 5215–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, N.; Li, M.; An, W. Spiking Swin Transformer for UAV Object Detection Based on Event Cameras. In Proceedings of the 2024 12th International Conference on Information Systems and Computing Technology (ISCTech), Xi’an, China, 8–11 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lele, A.S.; Raychowdhury, A. Fusing frame and event vision for high-speed optical flow for edge application. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Austin, TX, USA, 28 May–1 June 2022; pp. 804–808. [Google Scholar]

- Mueggler, E.; Huber, B.; Scaramuzza, D. Event-based, 6-DOF pose tracking for high-speed maneuvers. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–18 September 2014; pp. 2761–2768. [Google Scholar]

- Rueckauer, B.; Delbruck, T. Evaluation of event-based algorithms for optical flow with ground-truth from inertial measurement sensor. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barranco, F.; Fermuller, C.; Aloimonos, Y.; Delbruck, T. A dataset for visual navigation with neuromorphic methods. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Li, A.; Li, T.; Yu, W.; Zou, D. M2dgr: A multi-sensor and multi-scenario slam dataset for ground robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 7, 2266–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmerico, J.; Cieslewski, T.; Rebecq, H.; Faessler, M.; Scaramuzza, D. Are we ready for autonomous drone racing? The UZH-FPV drone racing dataset. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 6713–6719. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffregen, T.; Gallego, G.; Drummond, T.; Kleeman, L.; Scaramuzza, D. Event-based motion segmentation by motion compensation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7244–7253. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, A.Z.; Thakur, D.; Özaslan, T.; Pfrommer, B.; Kumar, V.; Daniilidis, K. The multivehicle stereo event camera dataset: An event camera dataset for 3D perception. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, M.; Aarents, W.; Gehrig, D.; Scaramuzza, D. Dsec: A stereo event camera dataset for driving scenarios. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 4947–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burner, L.; Mitrokhin, A.; Fermüller, C.; Aloimonos, Y. Evimo2: An event camera dataset for motion segmentation, optical flow, structure from motion, and visual inertial odometry in indoor scenes with monocular or stereo algorithms. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.03467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecq, H.; Gehrig, D.; Scaramuzza, D. Esim: An open event camera simulator. In Proceedings of the Conference on robot learning, PMLR, Zurich, Switzerland, 29–31 October 2018; pp. 969–982. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore, N.; Mian, S.; Abidi, C.; George, A.D. A neuro-inspired approach to intelligent collision avoidance and navigation. In Proceedings of the AIAA/IEEE Digital Avionics Systems Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 11–16 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubâa, A. Robot Operating System (ROS); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrig, D.; Gehrig, M.; Hidalgo-Carrió, J.; Scaramuzza, D. Video to events: Recycling video datasets for event cameras. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 3586–3595. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia, R.; Rodríguez-Gómez, J.; Sanchez-Diaz, J.; Gañán, F.; Rodríguez, I.; Luna-Santamaria, J.; Dios, J.M.-D.; Ollero, A. A comparison between framed-based and event-based cameras for flapping-wing robot perception. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023; pp. 3025–3032. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Cioffi, G.; De Visser, C.; Scaramuzza, D. Autonomous quadrotor flight despite rotor failure with onboard vision sensors: Frames vs. events. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gomez, J.P.; Eguiluz, A.G.; Martínez-De-Dios, J.R.; Ollero, A. Auto-Tuned Event-Based Perception Scheme for Intrusion Monitoring with UAS. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 44840–44854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Operation | Gaps |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Vision Sensors (DVSs) [28] | Detecting variations in brightness is the sole method used by DVS, the most popular kind of event camera. When the amount of light in the scene varies enough, each pixel in a DVS independently scans the area and initiates an event. With their high temporal resolution and lack of motion blur, DVSs work especially well in situations involving rapid movement. The DVS has a number of benefits over conventional high-speed cameras, one of which being their incredibly low data rate, which qualifies them for real-time applications. | Despite these capabilities, integrating DVSs with UAVs remains a challenge, especially on the issues of real-time processing and data synchronization [21]. A lack of standardized datasets is also making it difficult to evaluate the performance of DVS camera-based UAV applications [29] |

| Asynchronous Time-based Image Sensors (ATIS) [30] | ATIS combines the capability of capturing absolute intensity levels with event detection. Not only can ATIS record events that are prompted by brightness variations, but it can also record the scene’s actual brightness at times. Rebuilding intensity images alongside event data is made possible by this hybrid technique, which enables greater information acquisition and is especially helpful for applications that need both temporal precision and intensity information. | Data from an event-based ATIS camera can be noisy, especially in low-light conditions. So, there is a need for an efficient noise filtering model to address this [31] |

| Dynamic and Active Pixel Vision Sensor (DAVIS) [2] | DAVISs combine traditional active pixel sensors (APS) and DVS capability. Because of its dual-mode functionality, DAVISs may be used as an event-based sensor to identify changes in brightness or as a conventional camera to record full intensity frames. The DAVIS’s dual-mode capacity makes it adaptable to a variety of scenarios, including those in which high-speed motion must be monitored while retaining the ability to capture periodic full-frame photos. | This capability of combining both APS and DVS capability poses challenges in complex data integration and sensor fusion [32] |

| Color Event Cameras [33] | Color event cameras are one of the more recent innovations that increase the functionality of traditional DVSs by capturing color information. These sensors enable the camera to record color events asynchronously by detecting changes in intensity across various color channels using a modified pixel architecture. This breakthrough enables event cameras to be utilized in more complicated visual settings where color separation is critical. | There is a scarcity of comprehensive dataset repositories specifically for training and evaluating models that use this camera [34] |

| keywords | event based camera, event-based camera, dynamic vision sensor, dvs, unmanned aerial vehicle, uavs, drone |

| Databases | Scopus and Web of Science |

| Boolean operator | OR, AND |

| Language | English |

| Year of publication | 2015 to 2025 |

| Inclusion criteria | English, peer review journal articles and conferences proceeding, addressed the use of event cameras on DVSs in the context of UAVs |

| Exclusion criteria | Prior to 2015, not English, duplicate, focus was solely on hardware design or biological system without application in UAV |

| Document type | Published scientific papers in academic journals, conference papers |

| Symbol | Description | Units/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| I | Pixel intensity | Arbitrary units |

| (x, y) | Pixel coordinates in 2D image plane | Pixels |

| ∆ log(I) | Change in logarithmic intensity | Unitless |

| ∇ log(I) | Spatial gradient of the logarithmic intensity | Unitless |

| (dot u) | Motion field (spatial velocity of pixels) | Pixels per unit time |

| ∆t | Time interval | Seconds |

| C | Contrast threshold for triggering events | Threshold value |

| ek = (xk, tk, pk) | Event tuple: spatial coordinate, timestamp, polarity | xk in pixels; tk in seconds; pk ∈ {+1,−1} polarity indicator |

| δ (delta function) | Approximation of Dirac delta by Gaussian | Unitless, probability density function |

| Ω (Omega) | Image domain | Region within pixels |

| Mean intensity over the image domain | Intensity units | |

| θ (theta) | Parameters of motion or warp function | Typically includes angles and translations |

| Author | Year | DVS Type | Evaluation | Application/Domain | Model | Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [43] | 2015 | DVS 128 | Real indoor test flight with a miniature quadcopter | Navigation | Flexible algorithm infers motion from adjacent pixel time differences | The study targeted an indoor environment. Dynamic scenes with more complex environments are required. |

| [38] | 2019 | DVS 128 | Dataset from [29] | Vision aid landing | Adaptive block matching optical flow | Further work should focus on the robustness and the accuracy of landmark detection especially in a complex scene. |

| [22] | 2020 | SEES1 | Real-world experiment with quadrotor | Dynamic obstacle avoidance | (IMU)’s angular velocity average for ego-motion, DBSCAN for clustering and APF for obstacle avoidance | This approach model obstacles as ellipsoids and relies on sparse representation. Extending this approach to more complex environments with non-ellipsoidal obstacles and cluttered urban environments remains a challenge. |

| [44] | 2023 | Simulated DVS with resolution of 1024 × 768 | Simulator based on OSG-Earth | Navigation and control | Mutual information for image alignment | The algorithm is limited to 3-DoF displacement (translation) and does not incorporate changes in orientation, limiting its capability to fully determine the 6-DoF pose. |

| [45] | 2023 | DAVIC 240C | MVSCEC Dataset | Navigation | The author recommended a complete SLAM framework for high-speed UAV based on even camera | |

| [46] | 2024 | CeleX-5 | Real world with UAV and simulation with Unreal Engine and AirSim | Powerline inspection and tracking | The EAPTON (Event-based Antinoise Powerlines Tracking with ON/OFF Enhancement) | Lack of dataset in that domain and inability of the model to accurately distinguish between power lines and nonlinear object in a complex scene. |

| [47] | 2024 | DAVIS 326 | Real-world with octorotor UAV indoors and outdoors | Load transport; cable swing minimization | Point cloud representation and a Bézier curve combined with Nonlinear Model Predictive Controller | Future work could focus on enhancing event detection robustness during larger cable swings, developing more sophisticated fusion techniques, and extending the method’s applicability to dynamic, highly noisy environments. |

| Author | Year | Event Camera Type | Method of Evaluation | Application/Domain | Model | Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [53] | 2022 | DVS | The system was evaluated via simulation trials in Microsoft AirSim. | Event-based object detection, obstacle avoidance | Deep reinforcement learning | The study highlights the need to optimize network size for better perception range, design new reward functions for dynamic obstacles, and incorporate LSTM for improved dynamic obstacle sensing and avoidance in UAVs |

| [54] | 2022 | Prophese 640 by 480 | Real-world on small UAV | Localization and Tracking | YOLOv5 and k-dimensional tree | The research primarily focused on 2D tracking and future work should be extended to 3D tracking/control |

| [55] | 2023 | DAVIS346 | Real-world testing with a hexarotor UAV installed with both event- and frame-based cameras and simulation in Matlab Simulink | Visual servoing robustness | Deep reinforcement learning | The proposed DNN with noise protected MRFT lacks robust high-speed target tracking under noisy visual sensor data and slow update-rate sensors; future directions include developing adaptive system identification for high-velocity targets and optimizing neural network-based tuning to improve real-time accuracy under varying sensor delays and noise conditions |

| [56] | 2024 | Prophesee camera EVK4–HD | To bridge the data gap, the first large-scale high-resolution event-based tracking dataset called EventVot was produced through UAVs and used for real-world evaluation | Obstacle localization; navigation | Transformer-based neural networks | The high-resolution capability of the Prophesee EVK4–HD camera (1280 × 720) opens new avenues for improving event-based tracking, but it also introduces additional challenges, such as increased computational complexity and data processing requirements |

| [57] | 2024 | DAVIS 346c | Real-world testing in a controlled environment with hexacopter | Obstacle avoidance | Graph Transformer Neural Network (GTNN) | Real-world experiment in a complex environment is limited in the literature |

| [58] | 2024 | n.a | Real-world experiment with s500 quadrotor | Crack detection/inspection | Unet and YOLOv8n-seg network | Explore the use of actual event camera sensor to directly capture real temporal information |

| [59] | 2025 | DVS 128 | Evaluation was done using N-MNIST, N-CARS, CIFAR10-DVS dataset | Object detection | A motion-aware branch (MAB) enhances 2D CNNs | future research could focus on optimizing the input patches by filtering out meaningless or noisy patches before they are fed into MAB |

| Author | Year | Event Camera Type | Method of Evaluation | Application/Domain | Model | Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [64] | 2017 | DVS | Real-world recorded data from a DVS mounted on a QUAV | Obstacle avoidance | Spiking neural network model of LGMD | Integrate motion direction detection (EMD) and enhance sensitivity to diverse stimuli |

| [65] | 2019 | DVS240 | Real-world testing in indoor environment using the actual data from a DVS and simulation testing using data that was processed through an event simulator (PIX2NVS) | Drone detection | SNNs trained using spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP). | The model was tested in an indoor environment. Exploring the system in a resource-constrained environment is critical |

| [66] | 2020 | DAVIS240C | Real-world experiment on two-motor 1-DOF UAV | SLAM | PID+SNN | The authors suggested the potential for integrating adaptation mechanism and online learning into the SNN-based controllers by utilizing the chip’s on-chip plasticity |

| [67] | 2021 | DAVIS 240C | Real-world experiment on dualcopter | Autonomous UAV control | Hough transform with PD controller | Full on-chip neuromorphic integration for direct communication with flight controllers to reduce latencies and delays |

| [68] | 2023 | n.a | Simulated DVS implemented through the v2e tool within an AirSim environment | Obstacle avoidance | Deep Double Q-Network (D2QN) integrated with SNN and CNN | Improve network architecture for better performance in real world |

| [60] | 2023 | DAVIS 346 | Validated with simulated and collected datasets | Civil infrastructure inspection | DNN and SNN | Creating a real event-camera-based dataset for extreme illumination effects and testing SNNs on a real embedded neuromorphic device |

| [63] | 2024 | DVS 240 | Real drone | Autonomous UAV control | SNN and ANN | The author suggested the best approach to have an energy-efficient system is to make the entire drone system neuromorphic |

| [69] | 2024 | n.a | Simulation with Gazebo and ROS | Autonomous Control | SNN and ANN | A real-world simulation is suggested |

| [70] | 2024 | DVS | Real-world experiment with drone | People Detection | SNN STDP | The author suggested multi-person detection and implementation of neuromorphic chip for low power, low latency |

| [71] | 2024 | Prophese EVK4 HD | Neuromorphic MNIST (N-MNIST) dataset | Motion Estimation | Fuzzy SNN | Collecting actual event data in a mock Mars environment |

| [61] | 2024 | n.a | DDD17 dataset | Navigation | SNN with Surrogate Gradient Learning | Implementing the model on low-power neuromorphic hardware |

| [72] | 2024 | DVXplorer Mini camera | Simulation on neurorobotics platform | Asset Monitoring | SNN and Kalman filtering | Further research includes the port of optical flow computation to neuromorphic hardware and the full port of the system onto a real drone, for real-world assessment |

| [62] | 2024 | DVS | Simulation was performed in XTDrone-based | Obstacle avoidance | Dynamic neural field with Kalman filter | Deploy the lightweight SNN onto neuromorphic hardware for obstacle detection |

| [73] | 2024 | ESIM to generate the event | Synthetic data from ESIM | Obstacle avoidance | LGMD with FSN | Deploying the model in a complex scene |

| [74] | 2025 | n.a | Real-world experiment on drone | Obstacle avoidance | CEF and LEM | Extending the design principle beyond obstacle avoidance to navigation |

| Author | Year | Event Camera Type | Method of Evaluation | Application/Domain | Model | Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [39] | 2018 | DVS | The result was evaluated with [29] dataset | SLAM | Hybrid state estimation combining data from event and standard cameras and IMU. | Future work should expand this multimodal sensor to more complex real-world applications |

| [76] | 2021 | DVX Explorer 640 by 480 | Real-world quadrotor | Object detection and avoidance | Fuses IMU/depth. | Integrating avoidance algorithms based on motion planning, which would consider static and dynamic scenes |

| [75] | 2022 | DAVIS 346 | 6DOF quadrotor, using dataset from [40] | VIO | VIO model combining event camera, IMU, and depth camera for range observations. | According to the author, the effect of noise and illumination on the algorithm is worth studying in the next step |

| [77] | 2023 | DAVIS346 | Real-world in a static and dynamic environment using AMOV-P450 drone | Motion tracking and obstacle detection | It fuses asynchronous event streams and standard image utilizing nonlinear optimization through Photometric Bundle Adjustment with sliding windows of keyframes, refining pose estimates. | Future work aims to incorporate edge computing to accelerate processing |

| [78] | 2024 | Prophesee EVK4-HD sensor | Two insulator defect datasets, CPLID and SFID | Power line inspection | YOLOv8. | While the experiment used reproduced event data derived from RGB images, the authors note that real-time captured event data could better exploit the advantages of neuromorphic vision sensors |

| [79] | 2024 | n.a | Simulated data and real-world nighttime traffic scenes captured by a paired RGB and event camera setup on drones | Object Tracking | Dual-input 3D CNN with self-attention. | Integration of complementary sensors such as LIDAR and IMUs for depth-aware 3D representations and more robust object tracking |

| [80] | 2024 | Real-world testing on quadrotor both indoors and outdoors | VIO | PL-EVIO which tightly coupled optimization-based monocular event and inertial fusion. | Extending the work to event-based multi-sensor fusion beyond visual-inertial, such as integrating LiDAR for local perception and visible light positioning or GPS for global perception, to further exploit complementary sensor advantages |

| Cited Works | Application Area | Challenges/Future Directions |

|---|---|---|

| [29,39,41,43,55,75,80,83,86,87,88,89,90] | Visual SLAM and Odometry | Performance degrades in low-texture or highly dynamic scenes; need for stronger sensor fusion (e.g., with IMU, depth); robustness under aggressive maneuvers. |

| [22,23,53,57,62,64,68,73,74,77,91,92,93,94,95,96] | Obstacle Avoidance and Collision Detection | Filtering noisy activations; setting adaptive thresholds in cluttered, multi-object environments; scaling to dense urban or swarming scenarios. |

| [80,81] | GPS-Denied Navigation and Terrain Relative Flight | Requires fusion with depth and inertial data for stability; limited long-term robustness; neuromorphic SLAM hardware still in early stages. |

| [32,58,60,78,82] | Infrastructure Inspection and Anomaly Detection | Lack of large, annotated datasets; absence of benchmarking standards; need for generalization across varied materials and lighting. |

| [1,27,45,46,52,54,56,70,76,79,84,97] | Object and Human Tracking in Dynamic Scenes | Sparse, non-textured data limits fine-grained classification; re-identification with event-only streams remains difficult; improved multimodal fusion needed. |

| [79,85,98,99] | High-Speed and Aggressive Maneuvering | Algorithms need to generalize from lab to real world; neuromorphic hardware maturity; power-efficiency vs. control accuracy trade-offs. |

| S/N | Name | Inventor | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ESIM (Event Camera Simulator) | [108] | 2018 | https://github.com/uzh-rpg/rpg_esim (accessed on 5 October 2025) |

| 2 | ESVO (Event-Based Stereo Visual Odometry) | [90] | 2022 | https://github.com/HKUST-Aerial-Robotics/ESVO (accessed on 5 October 2025) |

| 3 | UltimateSLAM | [40] | 2018 | https://github.com/uzh-rpg/rpg_ultimate_slam_open (accessed on 5 October 2025) |

| 4 | DVS ROS (Dynamic Vision Sensor ROS Package) | [99] | 2015 | https://github.com/uzh-rpg/rpg_dvs_ros (accessed on 5 October 2025) |

| 5 | rpg_evo (Event-Based Visual Odometry) | [111] | 2020 | https://github.com/uzh-rpg/rpg_dvs_evo_open (accessed on 5 October 2025) |

| Year | Event Camera Type(s) |

|---|---|

| 2015 | DVS 128 |

| 2017 | DVS |

| 2018 | DVS |

| 2019 | DVS 128, DVS 240 |

| 2020 | SEES1, DAVIS 240C |

| 2022 | Celex4 Dynamic Vision Sensor, DAVIS 346 |

| 2023 | DAVIS, DAVIS 240C, DAVIS 346, DAVIS 346c |

| 2024 | CeleX-5, Prophesee EVK4-HD, DAVIS 326 |

| 2025 | DVS346 |

| Algorithmic Category | Latency | Accuracy | Robustness | Energy Consumption | Notes/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry approach | Very low (microsecond-level) | Moderate to high in controlled/simple environments | Sensitive to noise, scene sparsity, and dynamic elements | Moderate, suitable for embedded systems | Mathematical rigor with optical flow, but limited in complex scenes and textureless environments |

| Learning-Based | Moderate, varies with model complexity | Generally high, can outperform model-based in complex tasks | Improved adaptability to complex and dynamic environments | High, due to training and inference overhead on DNN/GTNN models | Needs large labeled datasets with ground truth real-world validation limited |

| Neuromorphic | Ultra-low latency due to spike-based processing | Competitive, especially in reactive tasks | High robustness to motion blur and high dynamic range scenes | Very low power, hardware-accelerated (e.g., Intel Loihi) | Hardware scarcity and immature platforms restrict broad adoption |

| Hybrid/Fusion | Variable, depends on sensor fusion algorithms | Potentially highest due to multi-source data fusion | Enhanced robustness combining strengths of multiple sensors | Moderate to high, depending on system complexity | Integration challenges; immature simulation platforms and datasets |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Akanbi, I.; Ayomoh, M. Event-Based Vision Application on Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: A Systematic Review of Prospects and Challenges. Sensors 2026, 26, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010081

Akanbi I, Ayomoh M. Event-Based Vision Application on Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: A Systematic Review of Prospects and Challenges. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkanbi, Ibrahim, and Michael Ayomoh. 2026. "Event-Based Vision Application on Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: A Systematic Review of Prospects and Challenges" Sensors 26, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010081

APA StyleAkanbi, I., & Ayomoh, M. (2026). Event-Based Vision Application on Autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: A Systematic Review of Prospects and Challenges. Sensors, 26(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010081