4. Yolo-Based Semantic Segmentation Model

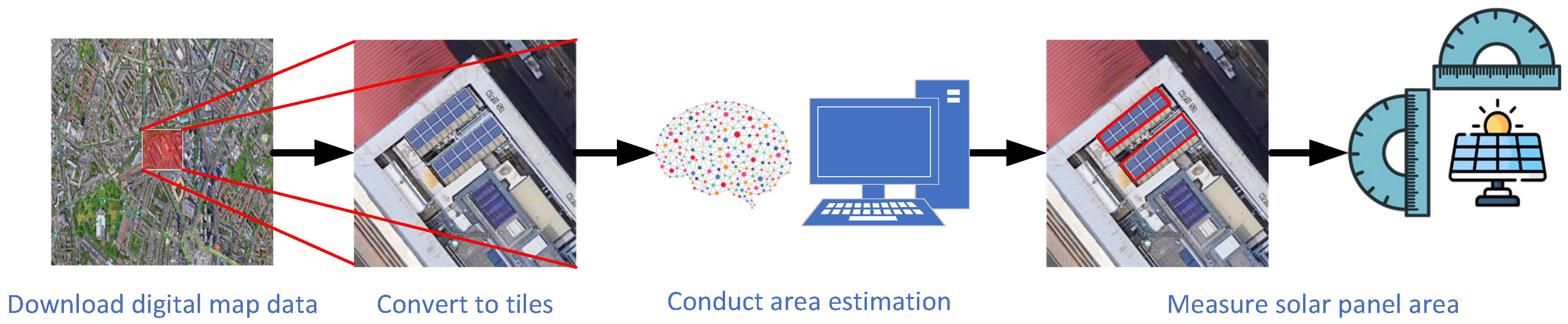

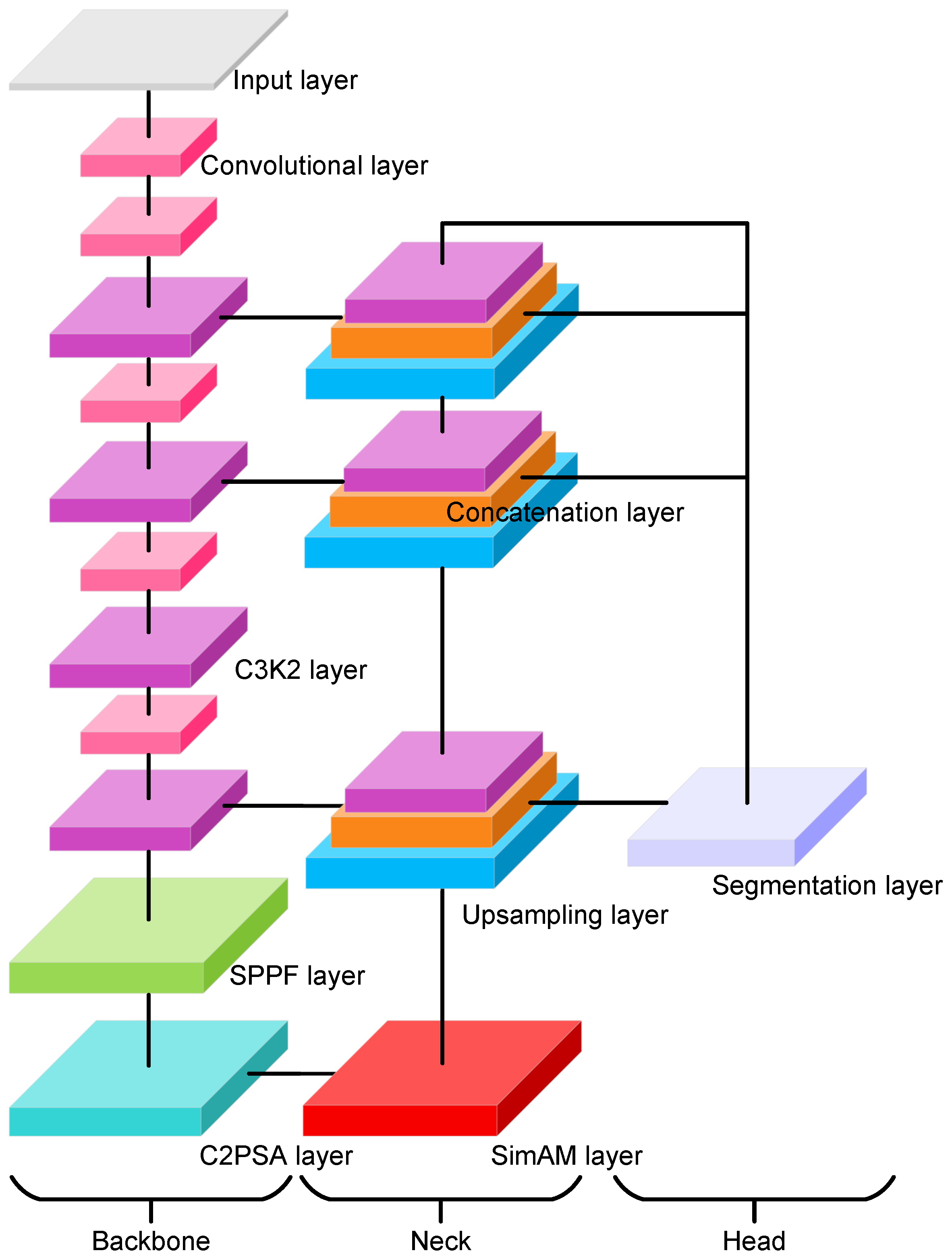

To compute the area of existing solar panels, the most critical step is to recognize and segment these solar panels. To this end, we develop a YOLO11x-seg based [

27,

28] objective segmentation model with an extra attention module (see

Figure 4) to compute the area of solar panels within the designated area. The YOLOv11x-seg model is an extension of the YOLO object detection framework, designed specifically for semantic segmentation tasks. It integrates the efficiency and speed of the YOLO architecture with advanced segmentation capabilities, enabling it to detect and segment objects simultaneously in real time. The model consists of a backbone module, a neck module, and a segmentation head module. The backbone module is a pretrained convolutional neural network that extracts feature maps from the input image; it is composed of several customized convolutional layers and C3k2 layers, an SPPF layer, and a C2PSA layer. In our modified architecture, the backbone further incorporates SimAM, a parameter-free neuron-level attention mechanism that adjusts the importance of spatial activations without introducing additional learnable parameters. The SimAM block is integrated at the end of the backbone to strengthen spatial feature discrimination, enabling the model to more effectively refine and highlight solar panel regions. The neck module is where features from the backbone are refined and passed to the segmentation heads. It consists of two repeated sequences of upsampling, concatenation, and C3k2 layers and two repeated sequences of convolutional, concatenation, and C3k2 layers. The segmentation head is used to perform pixel-wise classification to output a mask where each pixel corresponds to the solar panel class; it takes multi-scale feature maps from different pyramid layers and outputs detection predictions (bounding box, objectness, and class scores) along with a 32-dimensional mask coefficient vector for each instance. In parallel, a prototype network generates 256 prototype masks, which are linearly combined with the instance-specific coefficients to produce the final instance masks.

Table 1 summarizes the major training hyper-parameters and architectural settings adopted for the proposed model.

For an input image

, the designed framework first employs convolutional layers to extract features of solar panels at different scales. For the convolutional layers, it applies a

convolution with stride

and padding

to produce

output channels, followed by batch normalization to stabilize training and SiLU activation to increase nonlinearity. In our implementation, the YOLO-based downsampling convolutions adopt the standard configuration of kernel size

, stride

, and padding

, consistent with the default YOLO design for spatial reduction. The detailed equations of the convolutional layer are shown below:

where

denotes the output feature value corresponding to the

n-th input image at spatial position

of output channel

, with

and

.

represents the convolution kernel weights, and

is the bias term. Indices

and

refer to output and input channels, while

with

and

denote kernel offsets. Terms

,

, and

correspond to stride, padding, and dilation in the vertical and horizontal directions, respectively. The input tensor

I is indexed at positions

, and values outside the valid range are treated as zeros (zero padding).

The output spatial dimensions

and

are given by the following:

To stabilize training and accelerate convergence, the convolution output is normalized and re-scaled using batch normalization:

where

denotes the convolution output of the

n-th input feature map at spatial position

of channel

,

and

are the mean and variance of channel

computed over the mini-batch,

are learnable scale and shift parameters, and

is a small constant for numerical stability.

To introduce nonlinearity and enhance feature representation, a gating mechanism based on the sigmoid function is applied:

where

is the batch-normalized feature value,

denotes the sigmoid activation, and

represents the final output feature map after activation.

The convolutional layer is stacked in tandem with a C3k2 block. The C3k2 block is a variant of the cross-stage partial (CSP) structure designed to enhance feature representation while maintaining computational efficiency. In this block, the input feature map is first split along the channel dimension into two branches. The first branch, known as the shortcut branch, applies only a

convolution to preserve part of the input information with minimal transformation. The second branch, referred to as the residual branch, processes the features through two consecutive bottleneck blocks, where each bottleneck consists of a

convolution for channel reduction, a

convolution for spatial feature extraction, and a residual connection to retain original information. The outputs from these two branches are then concatenated along the channel axis and passed through a final

convolution to fuse the features, producing the output of the C3k2 block. By combining lightweight computation with deeper feature extraction, the C3k2 structure provides an effective balance between efficiency and representational power. The detailed equations of the C3k2 block are shown below.

where

is the input feature map,

represents the shortcut branch,

denotes two consecutive bottleneck transformations on the residual branch, Concat concatenates the two branches along the channel axis, and the outer

fuses the concatenated features into the final block output. To further enhance the representation capacity, we adopt the bottleneck structure defined as follows:

where

is the input feature map,

reduces the channel dimension,

extracts spatial features, and the residual addition preserves the original information while enhancing feature representation.

After feature extraction by the convolutional layers, the network employs an SPPF module followed by a C2PSA module. The SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling—Fast) module applies successive pooling operations with different receptive fields and concatenates the results, enabling the network to capture multi-scale spatial context efficiently. The C2PSA (cross-stage partial with parallel self-attention) module then integrates cross-stage partial connections with both channel and spatial attention mechanisms, which enhances long-range dependencies and improves the discriminative ability of the fused features.

where

X is the output feature map of Equation (

4),

,

, and

. Here, Concat denotes channel-wise concatenation of multi-scale pooled features, and

is used for dimensionality reduction and fusion.

where

X is the output feature map of Equation (

6),

are two splits of

X along the channel dimension, and

A is the attention-enhanced feature computed from

.

where CA denotes channel attention, SA denotes spatial attention, and

are balancing coefficients. The concatenated features are finally fused by a

convolution to form the block output.

After passing through the SPPF and C2PSA modules, the feature map is further refined by a SimAM (Simple Attention Module) block [

29]. The SimAM module introduces a parameter-free attention mechanism that adaptively emphasizes informative regions while suppressing less relevant responses, thereby improving the representational power of the extracted features without additional learnable parameters. Together, the SPPF, C2PSA, and SimAM modules enhance the features in a complementary manner: SPPF captures multi-scale spatial context, C2PSA strengthens long-range dependencies via channel and spatial attention, and SimAM highlights fine-grained salient information, resulting in richer and more discriminative feature representations.

where

denotes the feature value at spatial position

of channel

c in the

n-th input feature map. Terms

and

are the mean and variance of the local region centered at

,

is a balancing coefficient,

is a temperature scaling factor,

is the sigmoid function, and

is the refined feature after applying SimAM attention.

Following the SimAM block, the network adopts a neck module based on a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) structure. The neck is designed to fuse multi-scale features from different backbone stages and to enhance both high-level semantics and low-level spatial details. It consists of two repeated operations, each composed of upsampling, feature concatenation with the corresponding backbone output, and a C3k2 block (already defined in Equation (

4)). This hierarchical design ensures that shallow and deep features are integrated, enabling robust detection of objects at different scales.

where

, and

denote the feature maps extracted from backbone stages of third, fifth, and ninth layers with downsampling strides of 32, 16, and 8, respectively,

is a

upsampling operation (nearest-neighbor interpolation as defined in Equation (

13),

denotes channel-wise concatenation of two feature maps as defined in Equation (

14), and

is the transformation block defined in Equation (

4). Here,

and

are the fused feature maps generated at the first and second stages of the neck, respectively.

where

is the input feature map,

r is the upsampling factor (typically

),

is the upsampled feature map, and

indexes the spatial coordinates of the output, while

denotes the corresponding location in the input feature map.

where

and

are two input feature maps with the same spatial size, and the output

is obtained by concatenating

and

along the channel dimension.

The segmentation head is designed to generate instance-specific masks in parallel with bounding box and class predictions. It consists of two branches: a prototype branch that produces a fixed set of global prototype masks shared across all instances, and a coefficient branch that predicts a coefficient vector for each detected instance. The final instance masks are obtained by linearly combining the prototype masks with the predicted coefficients, followed by sigmoid activation and optional cropping within the bounding boxes. All parameters are optimized end-to-end using a segmentation loss, which ensures that prototypes, projection weights, and coefficients are learned jointly during training. The overall formulation of the segmentation head is expressed as follows:

where

denotes the prototype masks generated from the input feature maps

F by function

with parameters

;

is the projection matrix, and

denotes its

-th element mapping prototype channel

c to the reduced channel

r;

is the bias vector with

its

r-th component;

is the coefficient vector for the

n-th instance predicted by function

with parameters

;

is the sigmoid activation; and

is the predicted mask probability at spatial position

for instance

n. Here,

indexes the reduced (projected) channels,

indexes’ prototype channels, and we set

in our experiments.

The reduced prototype representation is obtained through a

convolution as follows:

where

is the projection matrix,

is the bias vector, with

denoting its

r-th component, and

denotes the reduced prototype at spatial position

for channel

r.

The final instance mask is generated by linearly combining the reduced prototypes with the predicted coefficients as follows:

where

denotes the sigmoid activation, and

is the soft mask probability at spatial position

for instance

n.

The segmentation loss function used to supervise mask learning is defined as follows:

where

N is the number of instances,

is the ground-truth mask for instance

n,

and

are the binary cross-entropy and Dice loss functions, respectively, and

are their balancing weights.

During training, the segmentation loss is minimized with respect to all parameters of the segmentation head, and the gradients are propagated through the entire architecture in a unified manner. Specifically, the error signals flow from the final mask predictions back to the instance coefficients and their prediction branch , while simultaneously being transmitted to the projection weights and the prototype representations , and are further propagated to update the parameters of the prototype generator . In this way, the prototype masks, the projection matrix, and the instance coefficients are jointly optimized, enabling the model to learn coherent and discriminative mask representations in an end-to-end fashion.

To explicitly describe how the segmentation loss propagates gradients through the segmentation head, we decompose the overall gradient flow as follows:

where

is the set of predicted masks for all instances,

are the prototype masks generated by the prototype branch with parameters

,

are the projection weights, and

are the instance-specific coefficient vectors predicted by the coefficient branch with parameters

.

The gradient with respect to the instance coefficients is given by the following:

where

is the

r-th coefficient of instance

n,

are the reduced prototypes, and

is the derivative of the sigmoid function.

Similarly, the gradient with respect to the projection weights is as follows:

where

is the element of the projection matrix mapping prototype channel

c to the reduced channel

r,

is the

c-th prototype at spatial position

, and

is obtained by backpropagation from Equation (

20).

The gradient with respect to the prototypes is as follows:

where

is the prototype value at channel

c and location

, and the gradient accumulates from all reduced channels via

.

The gradient with respect to the prototype branch parameters is expressed as follows:

where

are the learnable parameters of the prototype generator

, and

denotes the prototype feature value at channel

c and spatial position

.

Similarly, the gradient with respect to the coefficient branch parameters is as follows:

where

are the learnable parameters of the coefficient prediction head

, and

is the

r-th coefficient for instance

n.

The total physical area of detected solar panels is estimated by converting the number of foreground pixels in the segmentation mask into square meters. This conversion relies on the ground resolution of the Web Mercator projection, expressed as

meters per pixel (mpp), which depends on the zoom level

z and the latitude

of the image center. When solar panels span across multiple tiled images, each visible portion is segmented independently, and the final area is obtained by summing pixel-level mask counts over all tiles. This aggregation strategy prevents both double-counting and underestimation in boundary regions, ensuring accurate estimation even when panels intersect tile borders. The final area is computed as the product of the pixel count and the squared ground resolution:

where

A denotes the estimated physical area in square meters (m

2),

represents the number of foreground pixels (solar panel pixels) in the segmentation mask, and

is the ground resolution in meters per pixel at latitude

and zoom level

z.

The ground resolution is defined as follows:

where

is the latitude of the image center (in radians when used in

),

z is the integer zoom level of the tile,

is the pixel dimension of the retrieved tile image (in our treatment,

),

T is the tile size in pixels (typically

), and

= 156,543.03392 m/pixel is the resolution factor at the equator for zoom level

in the Web Mercator projection.

5. Experiments and Discussion

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed model, the original YOLO11-seg model was also employed for comparison purposes. Both models were trained and fine-tuned on a mixed dataset, which consists of 22,112 satellite images in total. The dataset was split into three subsets to ensure robust training and evaluation: 70% (15,478 images) for training, 20% (4422 images) for validation, and the remaining 10% (2212 images) for testing. All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Ti GPU (12 GB VRAM), running Python 3.11 with PyTorch 2.9.1 and CUDA 13.0 acceleration. The proposed model contains 114 layers with 4.38 million parameters and 19.0 GFLOPs after fusion. During inference, the system achieves an average runtime of 1.7 ms per image, indicating that the network is highly efficient and suitable for large-scale satellite image segmentation tasks.

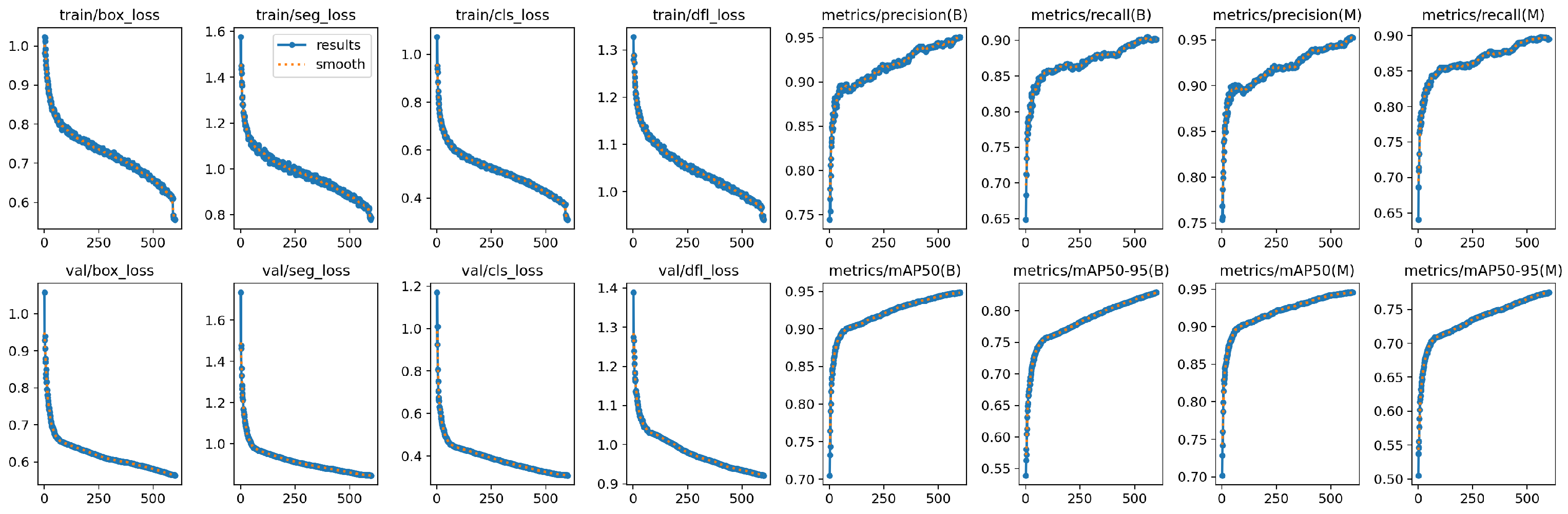

Figure 5 illustrates the training dynamics of the proposed model, including loss curves and evaluation metrics across 50 epochs. From the first row, it can be observed that the training losses for bounding box regression, segmentation, classification, and distribution focal loss steadily decrease, indicating stable convergence of the model. Similarly, the validation losses shown in the second row exhibit a consistent downward trend, confirming that the model generalizes well without obvious overfitting. The precision and recall curves for both bounding box detection (B) and mask segmentation (M) demonstrate continuous improvement, with precision reaching over 0.85 and recall stabilizing around 0.70 by the end of training. Furthermore, the mean Average Precision (mAP) at IoU threshold 0.5 (mAP50) reaches approximately 0.78 for bounding boxes and 0.72 for masks, while the stricter mAP50–95 metric reaches 0.60 and 0.52, respectively. These results suggest that the proposed model achieves robust detection and segmentation performance, with a favorable balance between precision and recall. The smoothness and stability of all curves further confirm the effectiveness of the adopted network design and training strategy.

Figure 6 presents sample qualitative results of the proposed segmentation model on the validation dataset. The model successfully detects and segments rooftop solar panels in high-resolution satellite imagery, with the predicted masks shown in blue overlaid on the original images. The results demonstrate that the model is able to accurately capture both the shape and spatial distribution of solar panels across varying roof orientations, scales, and background contexts. Although some overlaps between bounding boxes and masks can be observed due to densely arranged panels, the overall predictions align well with the ground-truth annotations, confirming the robustness of the model in handling complex urban environments.

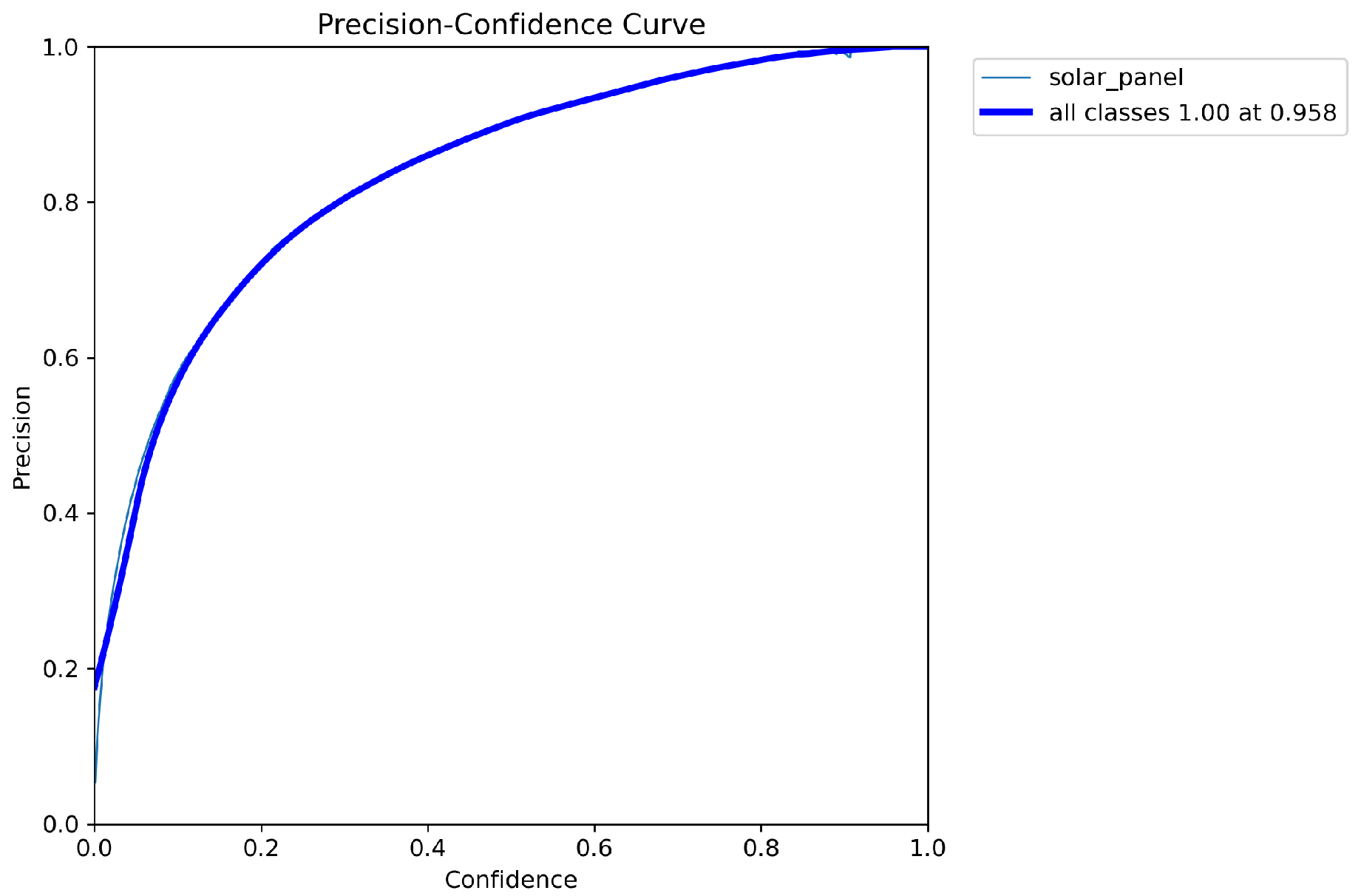

Figure 7 presents the precision–confidence curve for the solar panel segmentation task based on mask predictions. The precision steadily improves as the confidence threshold increases, reaching 1.0 at approximately 0.952 confidence. This trend indicates that the model is highly reliable in distinguishing true positives when stricter confidence criteria are applied, effectively eliminating false detections. Compared with lower confidence thresholds, where precision values fluctuate, the curve demonstrates that the model achieves robust segmentation performance when confidence is set above 0.5. Such characteristics are essential for practical deployment, where ensuring accurate mask-level detection is critical to avoid false segmentation of non-solar regions.

To comprehensively evaluate the segmentation quality of the proposed model, we employ three widely used metrics: Intersection over Union (IoU), F1-Score, and Pixel Accuracy. These metrics capture complementary aspects of segmentation quality: IoU measures the spatial overlap between predicted and ground-truth masks, F1-Score reflects the balance between precision and recall, and Pixel Accuracy quantifies global correctness across the entire image. Together, they provide a more complete and reliable assessment of model performance than any single metric alone. IoU is defined as

which measures the overlap between predicted masks and the ground truth. Although IoU is known to be sensitive to small objects and class imbalance, rooftop PV panels in our task form large, continuous regions where IoU provides a stable and meaningful measure of mask alignment. To mitigate the known limitations of IoU, we additionally report F1-Score and Pixel Accuracy, which together offer a more complete assessment of segmentation performance.

The F1-Score is expressed as

providing a balance between precision and recall. Pixel Accuracy is defined as

which evaluates the overall proportion of correctly classified pixels.

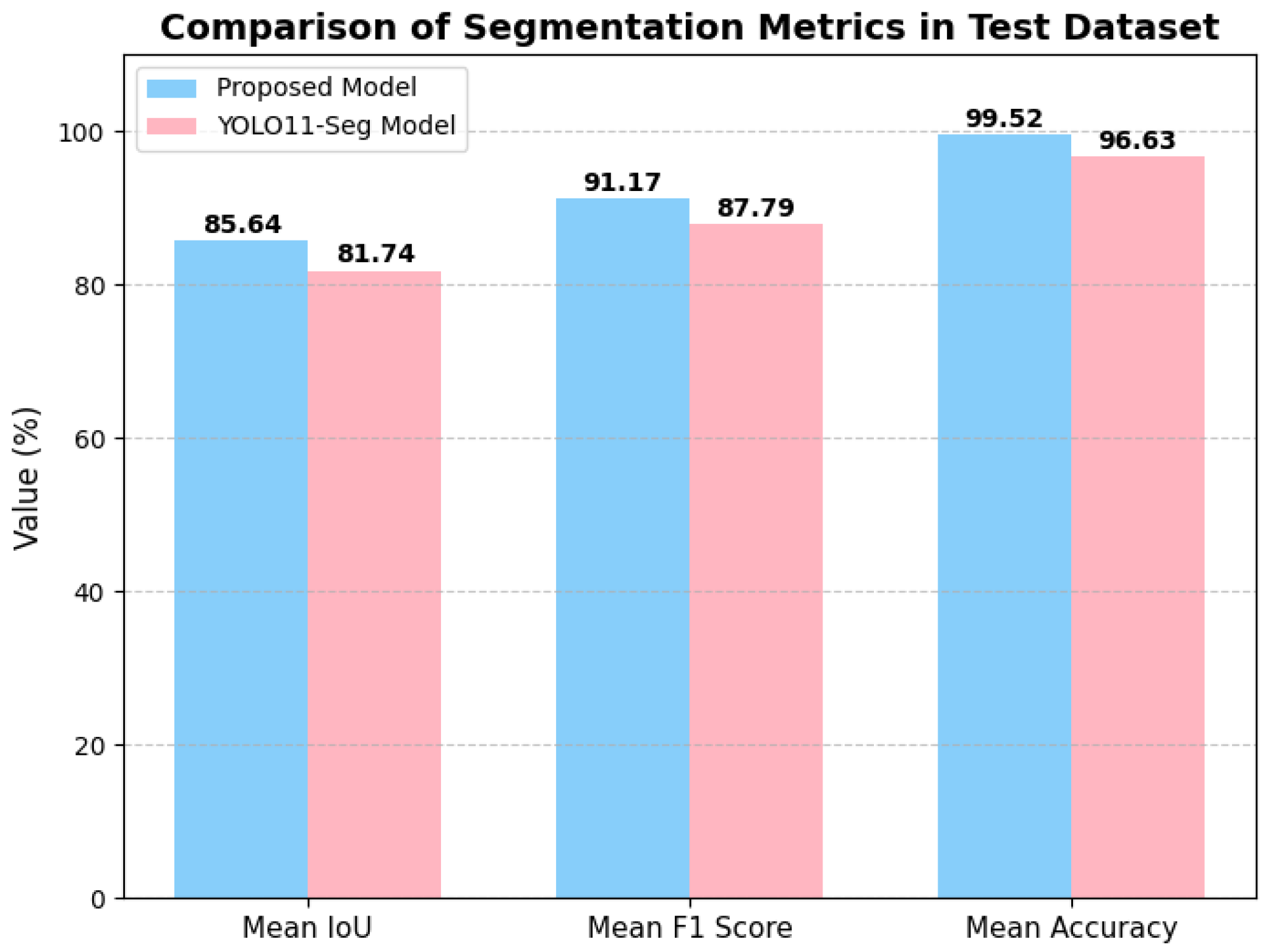

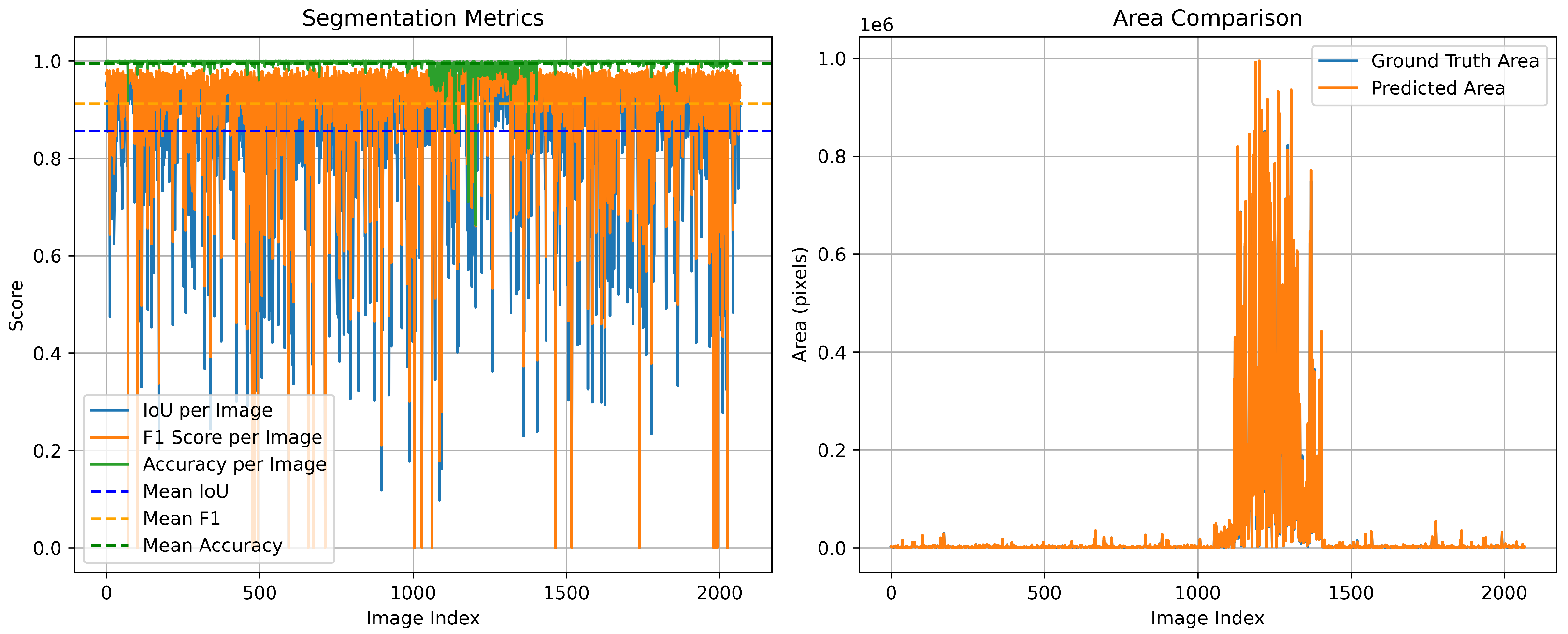

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the proposed model achieves consistently high performance, with mean IoU, F1-Score, and Accuracy reaching 0.8564, 0.9117, and 0.9952, respectively. In comparison, the baseline YOLO11-Seg model attains lower values of 0.8174, 0.8779, and 0.9663. This demonstrates that our proposed model provides a clear improvement across all three evaluation metrics. Furthermore, the area comparison in

Figure 9 demonstrates that the predicted segmentation areas closely follow the variations of the ground-truth areas, confirming that our method not only ensures pixel-level accuracy but also preserves global structural consistency.

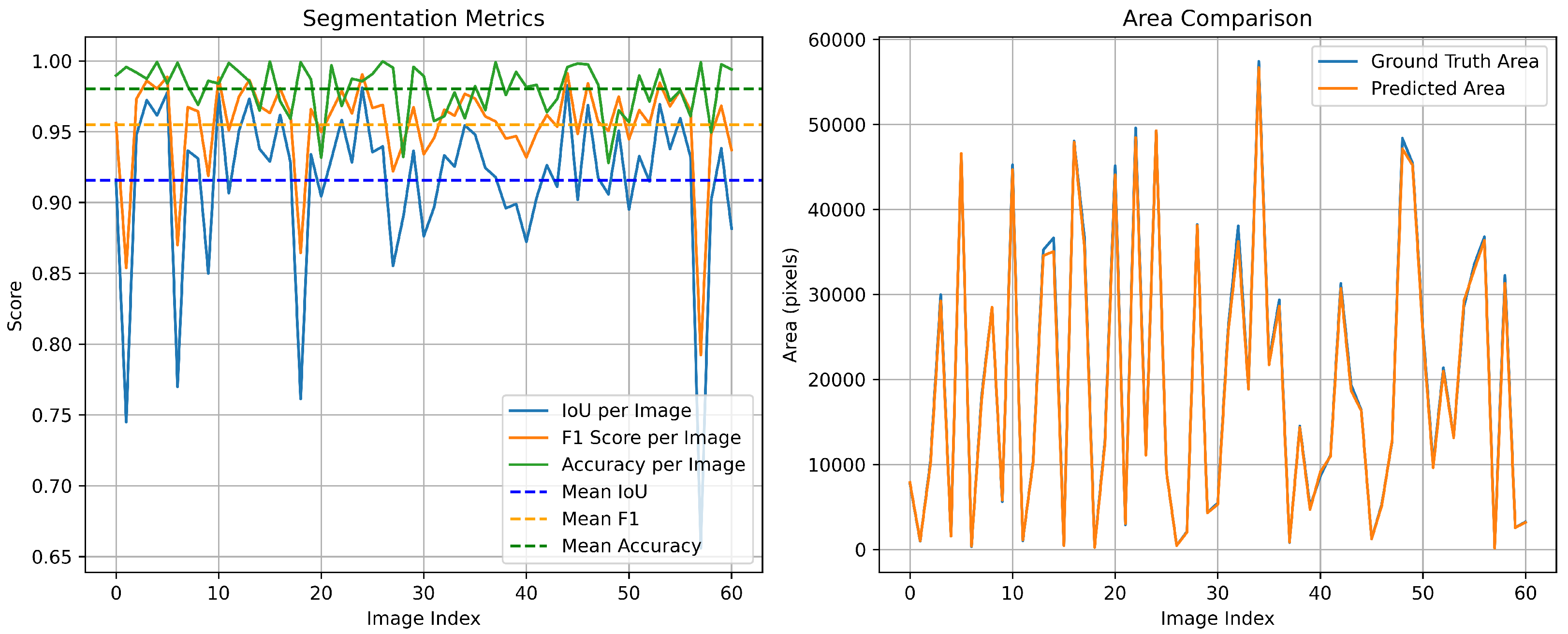

To further examine the robustness of the proposed segmentation model in shaded urban environments, we conduct an additional experiment on the PV01 rooftop subset of the Jiangsu multi-resolution dataset for photovoltaic panel segmentation [

24]. PV01 consists of 0.1 m UAV images of distributed rooftop PV installations in dense urban areas, where many rooftops are partially covered by cast shadows from neighboring buildings or trees. Such shadows often make PV modules visually similar to surrounding roof materials and dark background regions, and have been reported to reduce segmentation accuracy for small-scale rooftop systems. On the PV01 test split, our proposed model achieves segmentation performance with mean IoU of 0.9156, F1-Score of 0.9549, and Mean Accuracy of 0.9802 (see

Figure 10). These results suggest that the proposed method maintains good robustness in partially shaded urban scenes, although extreme shadow occlusions remain challenging and will be addressed in our future work.

As a case study, we conducted experiments in a designated study area located in the Elephant and Castle district of London, UK, as illustrated in

Figure 11. High-resolution satellite imagery of this area was obtained using the ESRI world imagery service. The selected region is bounded by the geographical coordinates (51.5020, −0.1097) and (51.4914, −0.0898), covering the Elephant and Castle area, and was divided into image tiles of size

. The tiled satellite images were processed through the proposed segmentation framework, and the real-world area was computed by converting pixel counts using the meter-per-pixel factor (see Equations (

25) and (

26)) derived from the zoom level and the (x, y) tile indices stored in each image filename. These indices uniquely determine the tile’s geographic position and allow accurate estimation of ground resolution. After segmentation, all detected rooftop PV regions were manually inspected and corrected to ensure the reliability of the final measurement. Following this refined procedure, the total rooftop solar panel area in the study region was determined to be 127.75 m

2.