1. Introduction

Due to the rapid advancement of intelligent technologies, robotics has found applications across multiple domains [

1,

2]. Currently, the most prevalent are service robots, capable of performing tasks beneficial to humans. As a subset of service robots, delivery robots are increasingly deployed in venues such as hotels, restaurants, and shopping centers. Given the complexity of restaurant environments, path planning technology has emerged as pivotal element in enabling delivery robots to navigate to their destinations [

3]. Path planning algorithms for delivery robots are primarily categorized into two types: global path planning and local path planning [

4]. During operation, delivery robots require not only effective global path planning to determine optimal routes but also local path planning with obstacle avoidance capabilities to navigate dynamically changing obstacles.

In robot path planning, common algorithms employed for global path planning include the A* algorithm [

5], rapidly exploring random tree (RRT) [

6], the genetic algorithm (GA) [

7], sparrow search algorithm (SSA) [

8], and ant colony optimization (ACO) [

9]. These algorithms each possess distinct advantages and are widely applied.

Among them, ACO, as a distributed intelligent bionic algorithm that simulates the mechanism of ants to find the shortest path between nest and food through pheromone communication, is widely cited in various fields. The ACO is robust because of its positive feedback mechanism and also has powerful global search capabilities. However, the ACO suffers from problems such as low search efficiency, slow convergence, and a tendency to fall into local optimization. In order to solve these problems, numerous researchers have extensively studied the ACO. Wu et al. and Li et al. both transformed the path planning problem into a multi-objective optimization problem through multiple comprehensive evaluation metrics. They, respectively, employed the farthest-point optimization strategy and multi-optimization strategies (such as non-uniform initial pheromone distribution and ε-greedy algorithms) to achieve more comprehensive path optimization [

10,

11]. Wu et al. advanced a novel variant of the ACO, which embeds information such as directional information and path turns into an enhanced heuristic function, improving the quality of paths and search efficiency [

12]. Zhang et al. developed an adaptive ant colony algorithm based on population information entropy, while Gao et al. incorporated backtracking and path merging strategies. Both approaches employed similar pheromone diffusion mechanisms for pheromone refinement, achieving a balance between path exploration and convergence speed or enhancing global search capabilities [

13,

14]. Cui et al. used deterministic state transfer probability rules to accelerate the convergence speed of the ACO and adaptive heuristic functions to optimize the number of turns and path length [

15]. Liang et al. applied an ACO to global path planning for deep-sea mining vehicles, while introducing a pheromone updating strategy with a reward-penalty mechanism and an angle-inspired state transfer probability to make the generated paths smoother [

16]. Liu et al. enhanced the guidance of pre-selected nodes during the initial search process through a pheromone concentration adaptive setting mechanism and also introduced a pseudo-random transfer strategy and dynamically adjusted pheromone volatilization rate to increase the population diversity and strengthen global search capability [

17]. Fu et al. designed a grid environment model based on bidirectional artificial potential fields and introduced potential fields into the environment to provide direction for the ants. They also used the potential energy difference between nodes to optimize the pseudo-random state transfer rule. This improvement enhanced the efficiency of path planning and avoided blind search [

18].

In addition to the above algorithms, there are a range of other effective path planning methods. For example, the A*, as a classical global path planning algorithm for static environments, has the advantages of being flexible, efficient, and generating relatively optimal paths, and is often used for path planning of mobile robots. Huang et al. proposed a 5-domain search method with the objective of improving efficiency and ensuring path smoothness [

19]. Xu et al. used exploration from both the starting point and the goal point to reduce the number of nodes to be explored, and also improved the A* algorithm by designing a new adaptive cost function and a Slide-Rail corner adjustment method to improve path security and smoothness [

20]. The RRT algorithm is a probabilistically complete algorithm for constructing a search tree by random sampling. Ganesan et al. solved the problems of slow convergence with uniform sampling and restricted exploration with non-uniform sampling by utilizing a path planning method with a mixed sampling RRT* that uses both non-uniform and uniform samplers [

21]. Li et al. proposed a knowledge-based GA with a novel path representation combining grids and coordinates and a new evaluation method to make it better adapted to very complex environments [

22]. The improved same-neighbor crossover operator and fitness function proposed by Lamini et al. for solving GA path planning problems in static environments resulted in a better average number of iterations and average number of transitions [

23]. To overcome the susceptibility of SSA to fall into local optima and slow convergence speed, Yan et al. proposed an improved SSA with better search accuracy and faster convergence speed in mobile robot path planning [

24].

The local path planning of the food delivery robot needs real-time adjustments according to the data collected by the sensors to ensure that the obstacle avoidance function can be achieved in complex environments. The commonly used local path planning algorithms are artificial potential field (APF) and dynamic window approach (DWA). Researchers enhance the performance of these algorithms by improving them. Liu et al. designed an improved method based on an environment-aware model for RRT guidance, which solves the problems of local minima, target inaccessibility, as well as local trajectory oscillations generated by the APF [

25]. In order to address the problem that traditional APF methods are prone to generating zigzag paths in self-driving vehicles, Li et al. designed a real-time path planning method for self-driving cars using the dynamically enhanced fireworks algorithm APF [

26]. Shin et al. considered localization accuracy in path planning and proposed a hybrid use of potential and localization risk fields to generate hybrid directed flows to guide driverless vehicles safely and efficiently [

27]. The DWA algorithm is also used as a classical and practical local path planning algorithm, which is applied in several fields owing to its strong applicability. Yao et al. advanced a fuzzy logic improved DWA to address the problem of poor robustness of the DWA as well as the non-smoothness of the path, which achieves better path length, smoothness and robustness [

28]. Zhang et al. improved the security and stability of local planning by introducing path smoothing coefficients and an improved DWA algorithm with a local goal selection strategy in path planning for USVs [

29]. When applying DWA to mobile robot formations, Cao et al. implemented several measures to enhance navigational safety. These included analyzing formation patterns and surrounding obstacle environments, evaluating velocity change coefficients, and designing safety obstacle avoidance distance evaluation coefficients [

30]. Wang et al. enabled agricultural robots to navigate more safely and autonomously in complex agricultural environments by integrating a dual-delay depth deterministic strategy gradient (TD3) into DWA and introducing an obstacle motion estimation module [

31]. Wang et al. designed a distributed optimization method and an event-triggered behavior switching strategy to enable UGV formations to harmonize formation maintenance, global navigation, and local obstacle avoidance [

32]. Abubakr et al. proposed an objective function weight that can optimize the DWA, considering the dynamic characteristics of the obstacles and the use of a fuzzy logic control system that can move quickly toward the target [

33]. Niu et al. enhanced the DWA algorithm by using the data acquired from high-precision sensors on the vehicle and utilizing an ACO to update the speed objective function in real time to address the DWA algorithm’s problem of irrational path planning and incapacity to balance speed and driving safety during the task of crossing substantial obstacles [

34]. Zhong et al. proposed a hybrid path planning algorithm based on an improved DWA, which enhances the obstacle avoidance effect and real-time path optimization of the DWA algorithm by using the A* algorithm to plan paths and avoid static obstacles in the operating environment, as well as by designing a target selection strategy and an improved method incorporating the speed barrier method [

35].

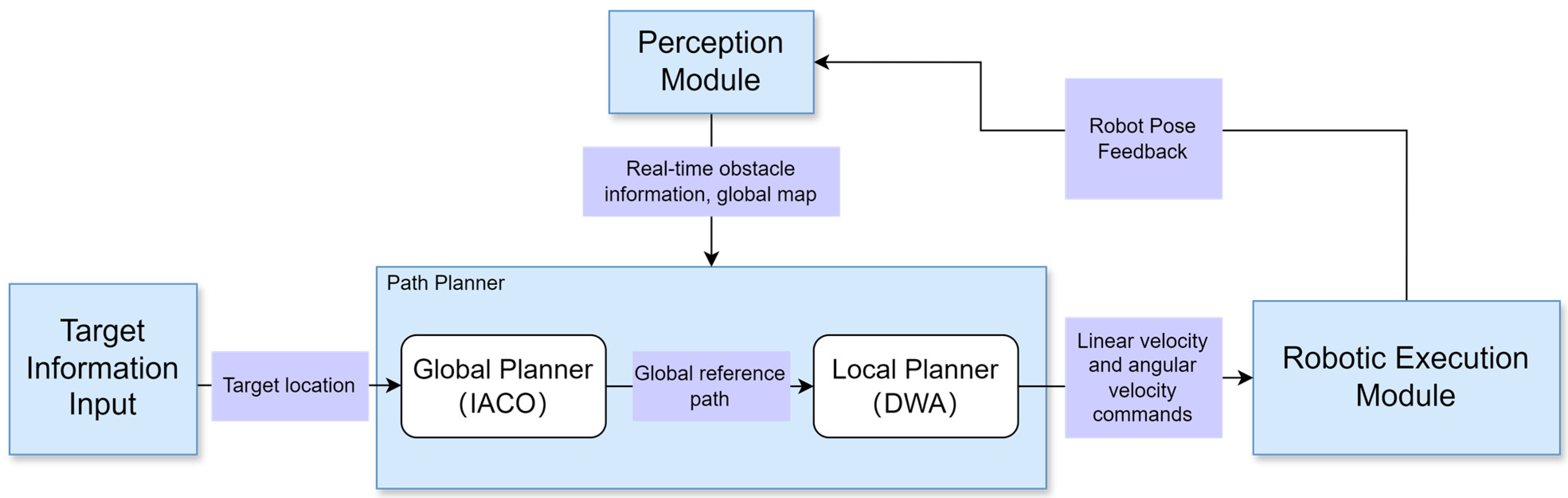

Figure 1 illustrates the general workflow of path planning integrated with control. For a mobile robot to accomplish a navigation process, it generally requires a closed-loop sequence involving perception, positioning, planning, and control. The robot moves from the starting point to the target point while avoiding obstacles and ensuring the optimal path. The perception module acquires the robot’s surrounding environment and its current pose; Path planners are employed to identify optimal routes. Hybrid path planning integrates the global optimization capabilities of global planners with the dynamic responsiveness of local planners, thereby achieving the dual objectives of global optimality and local safety. The execution module will perform real-time motion based on the path planner’s output (linear and angular velocities), while simultaneously feeding back the motion status and pose to the perception module and local planner, thereby forming a closed-loop control system.

The global and local path planning algorithms described in the aforementioned literature each exhibit certain limitations. Scene adaptability is limited, with most improved algorithms designed for specific environments (such as static grids), exhibiting insufficient generalization capabilities in complex dynamic scenarios featuring multiple moving obstacles and abrupt terrain changes. In environments with dense dynamic obstacles, there is insufficient integrated capability regarding real-time performance, safety, and path smoothness. This paper proposes an approach that combines an improved ACO with a DWA to address the constraints in both global and local path planning for delivery robots. The main contributions are as follows:

- (1)

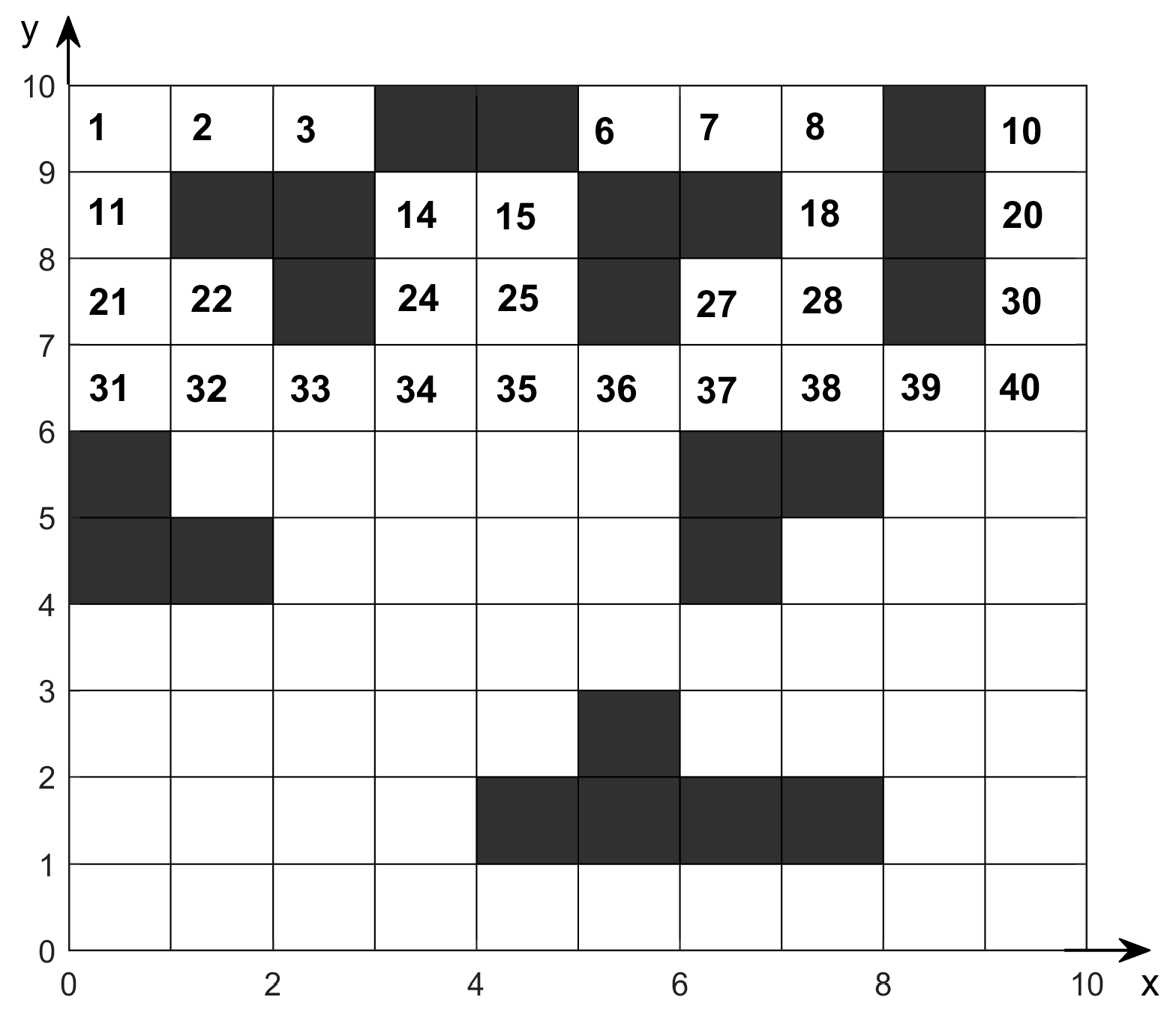

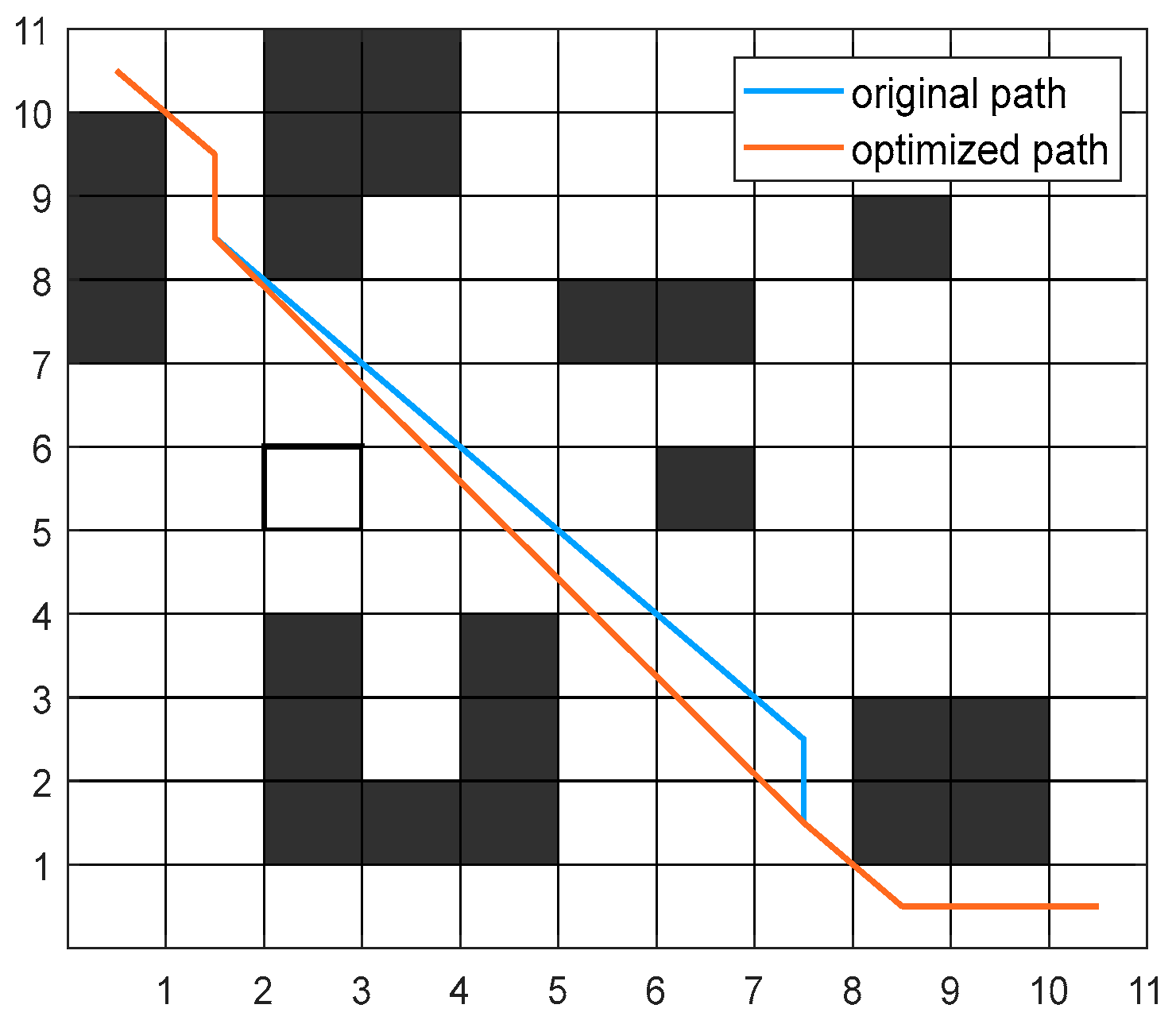

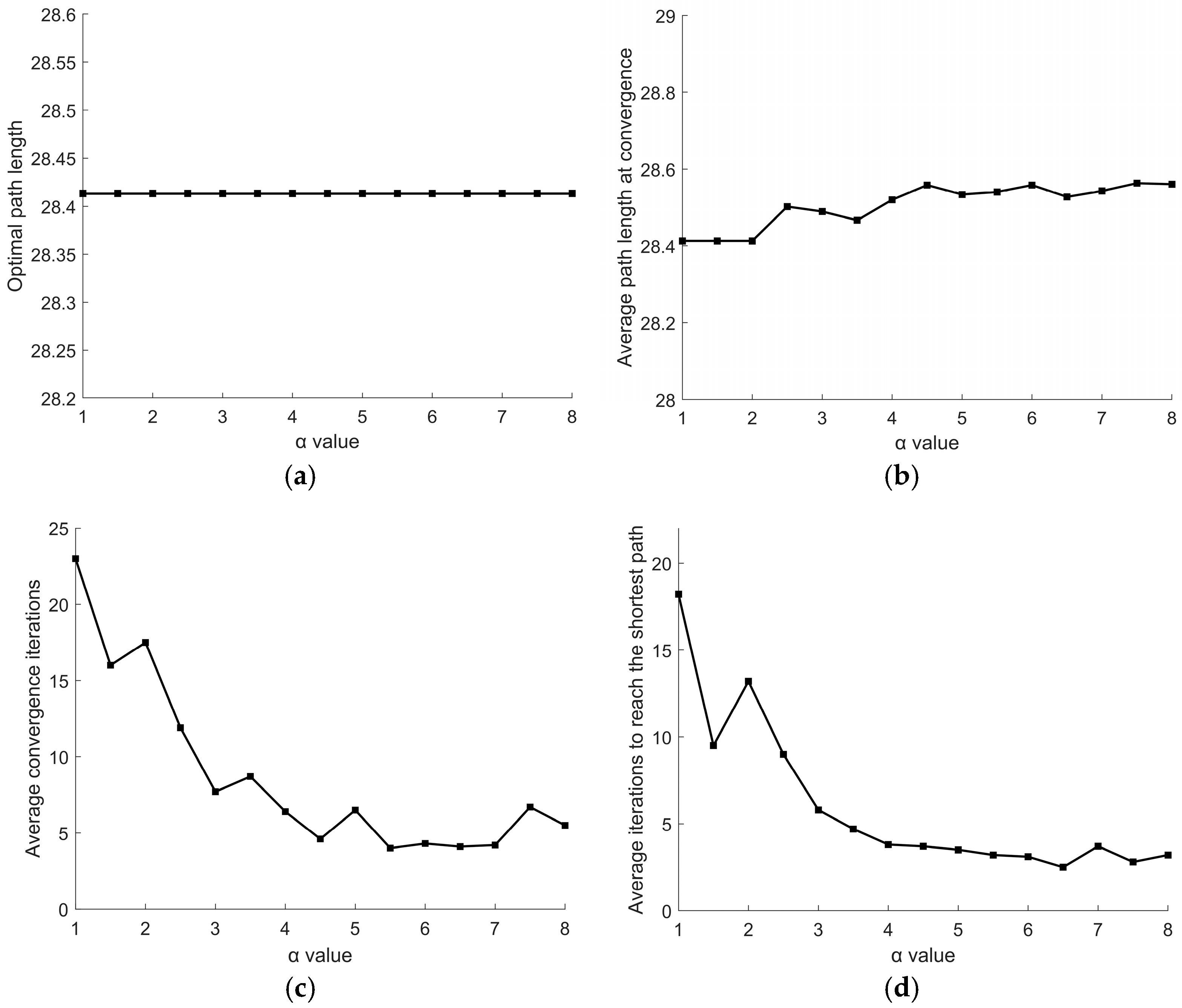

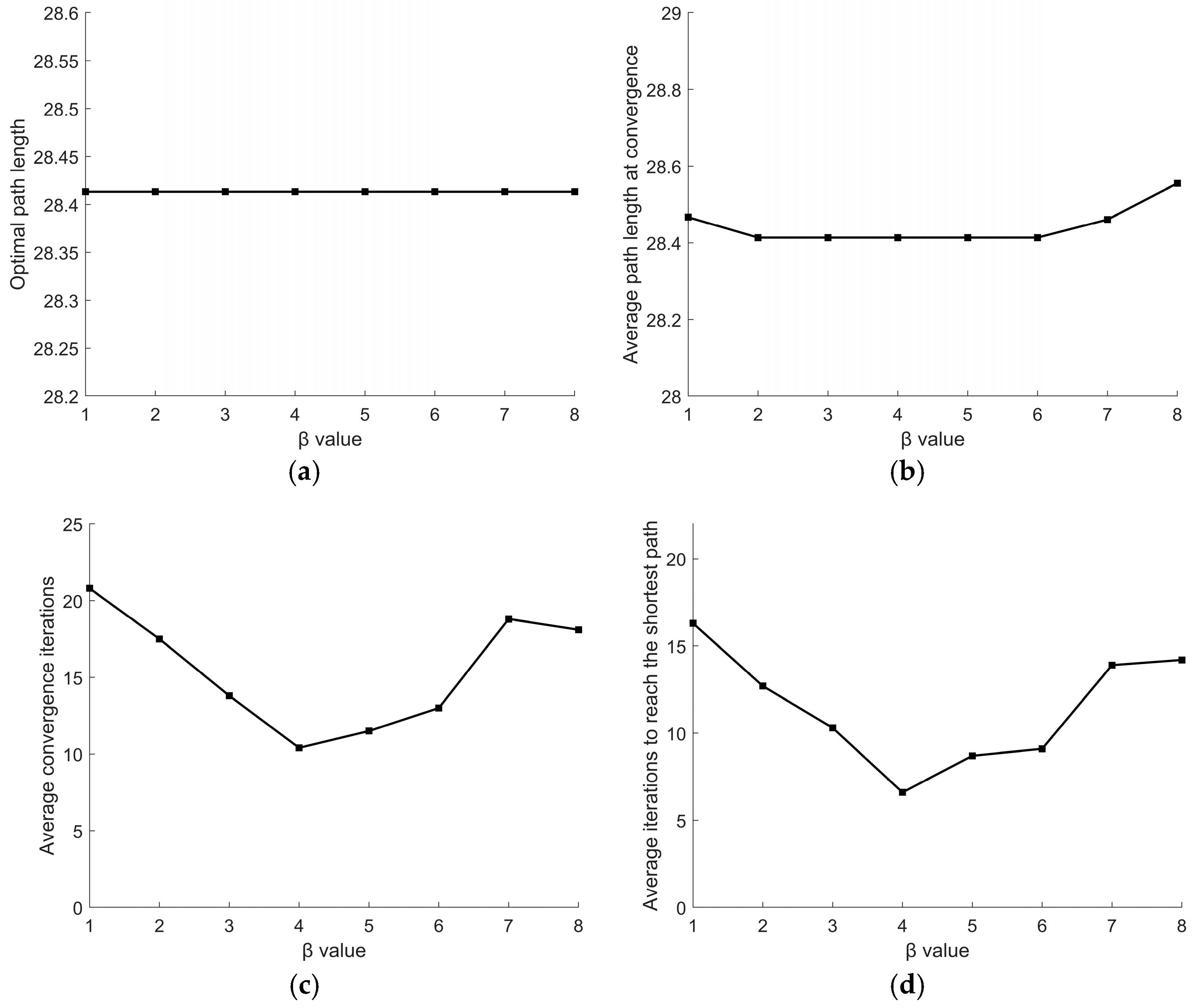

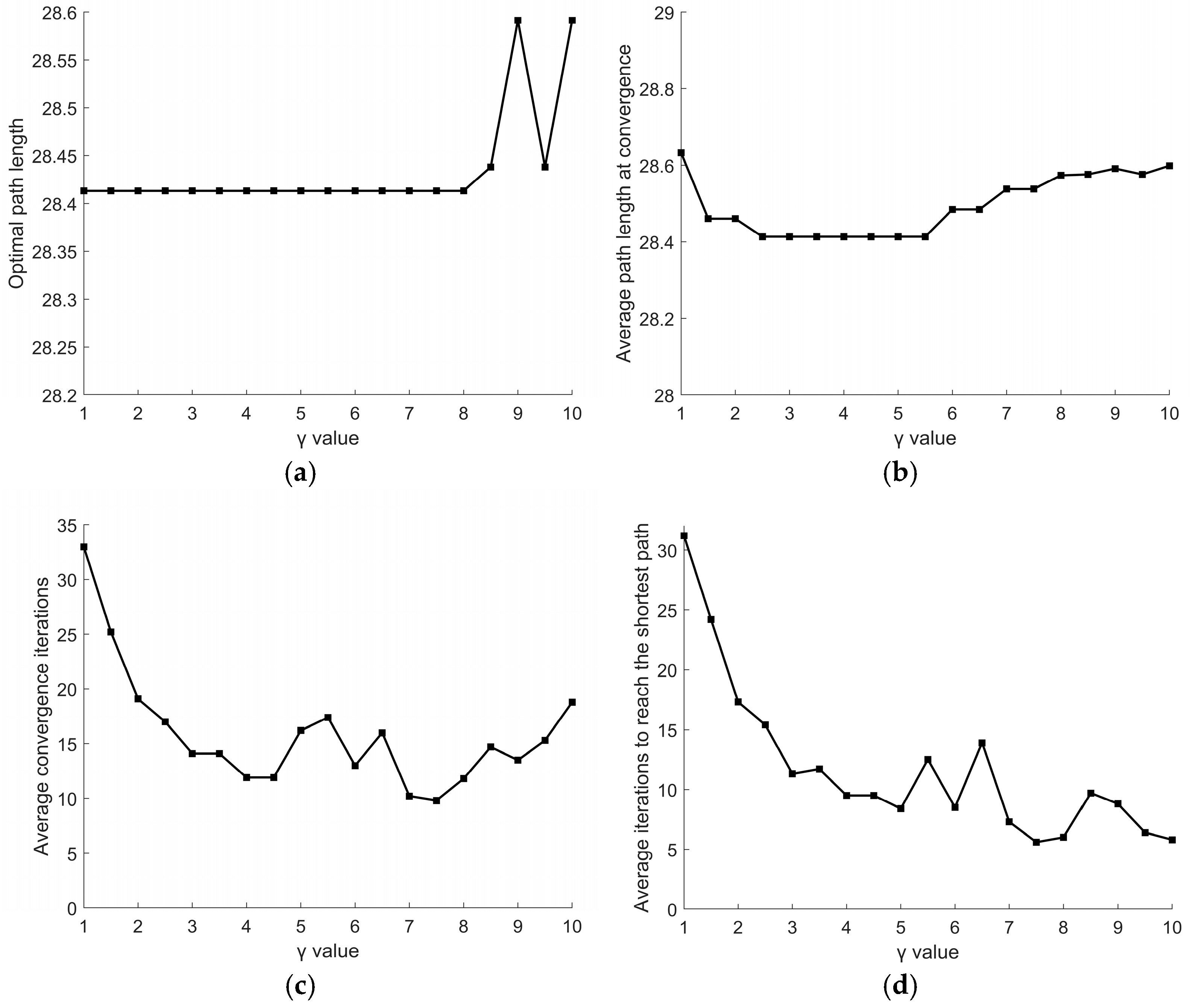

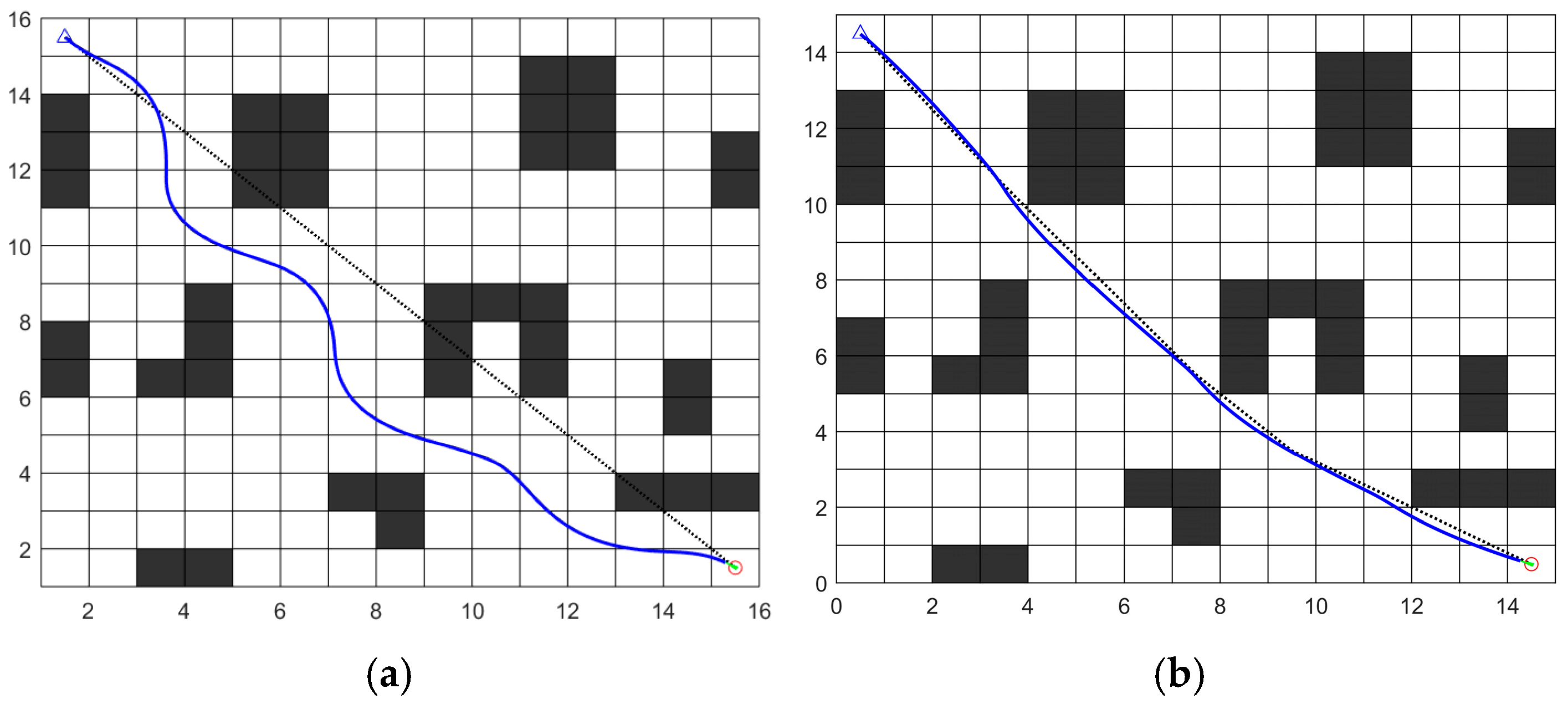

Improvements to the ACO employ the following strategies: A distribution strategy for initial pheromone concentration is determined by integrating node location data with obstacle information. New heuristics are constructed by incorporating a gravitational mechanism and directional angle heuristics to refine state transition probability rules. Pheromone update rules are implemented by sorting paths and augmenting superior paths with additional pheromone. Simultaneously, redundant turning points in paths are optimized to enhance path smoothness.

- (2)

Key nodes in global path planning are employed as target points for local paths. Dynamic obstacle distance evaluation subfunctions, linear velocity change evaluation subfunctions, and path proximity evaluation subfunctions are introduced. These are integrated with an IACO.

- (3)

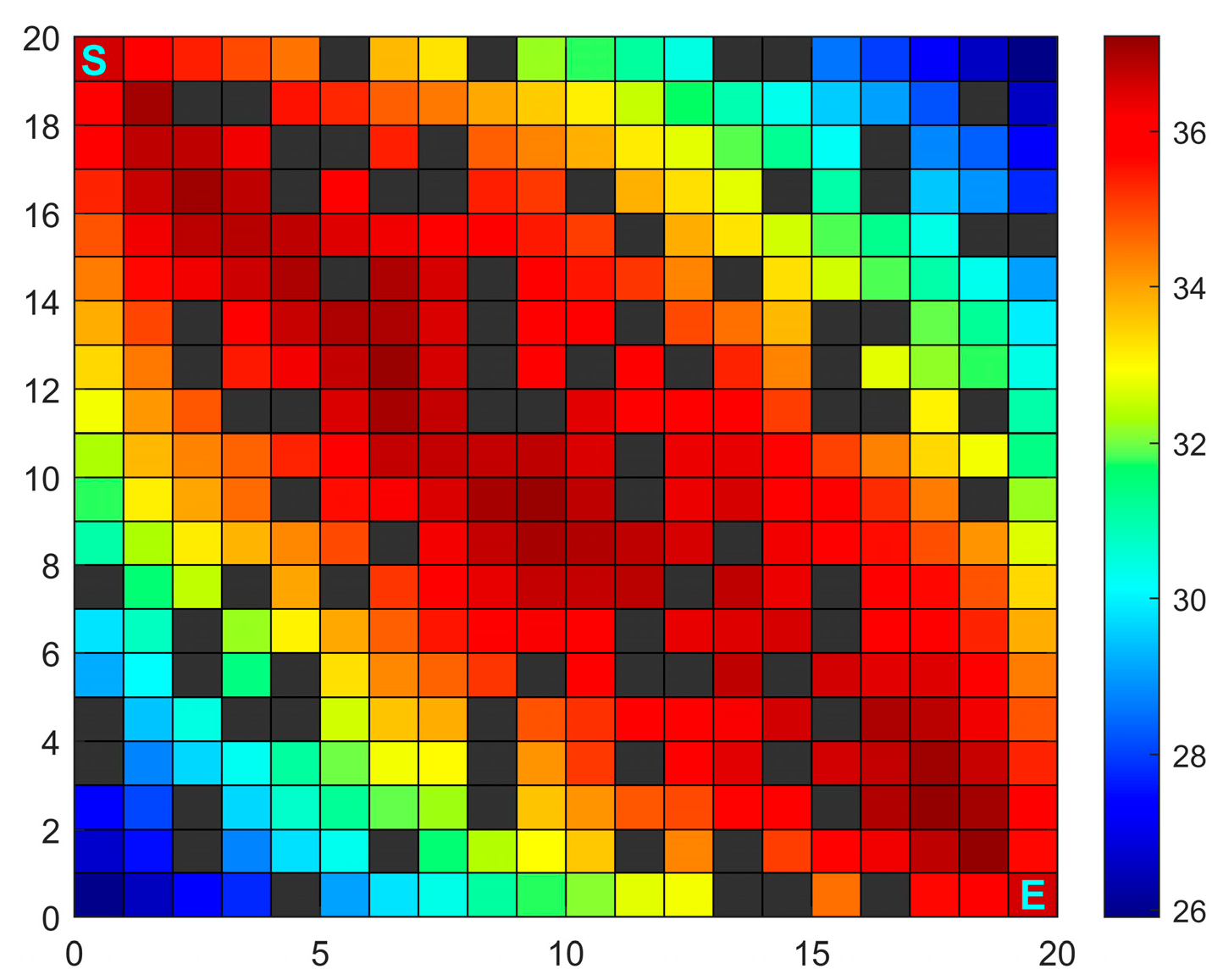

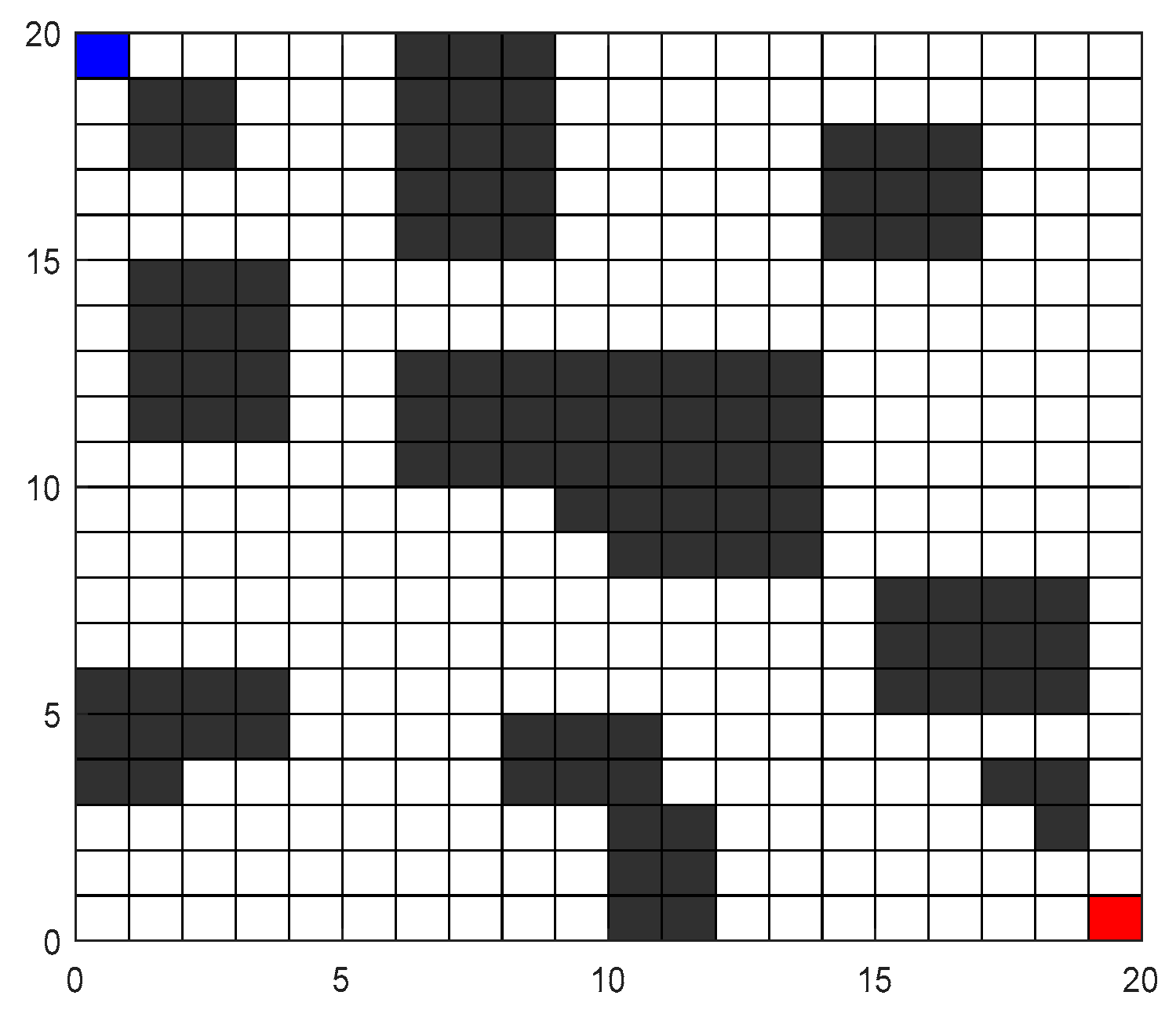

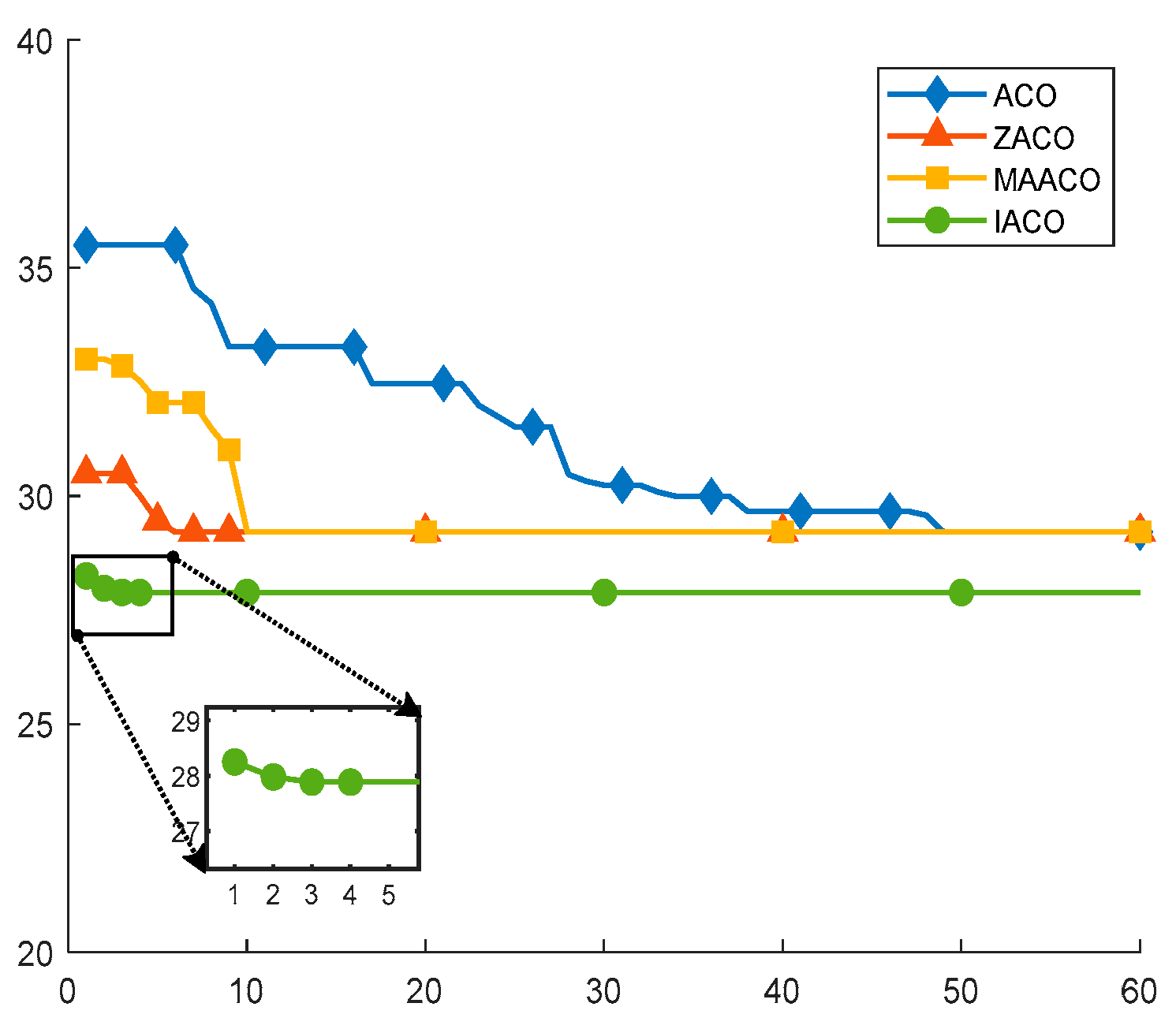

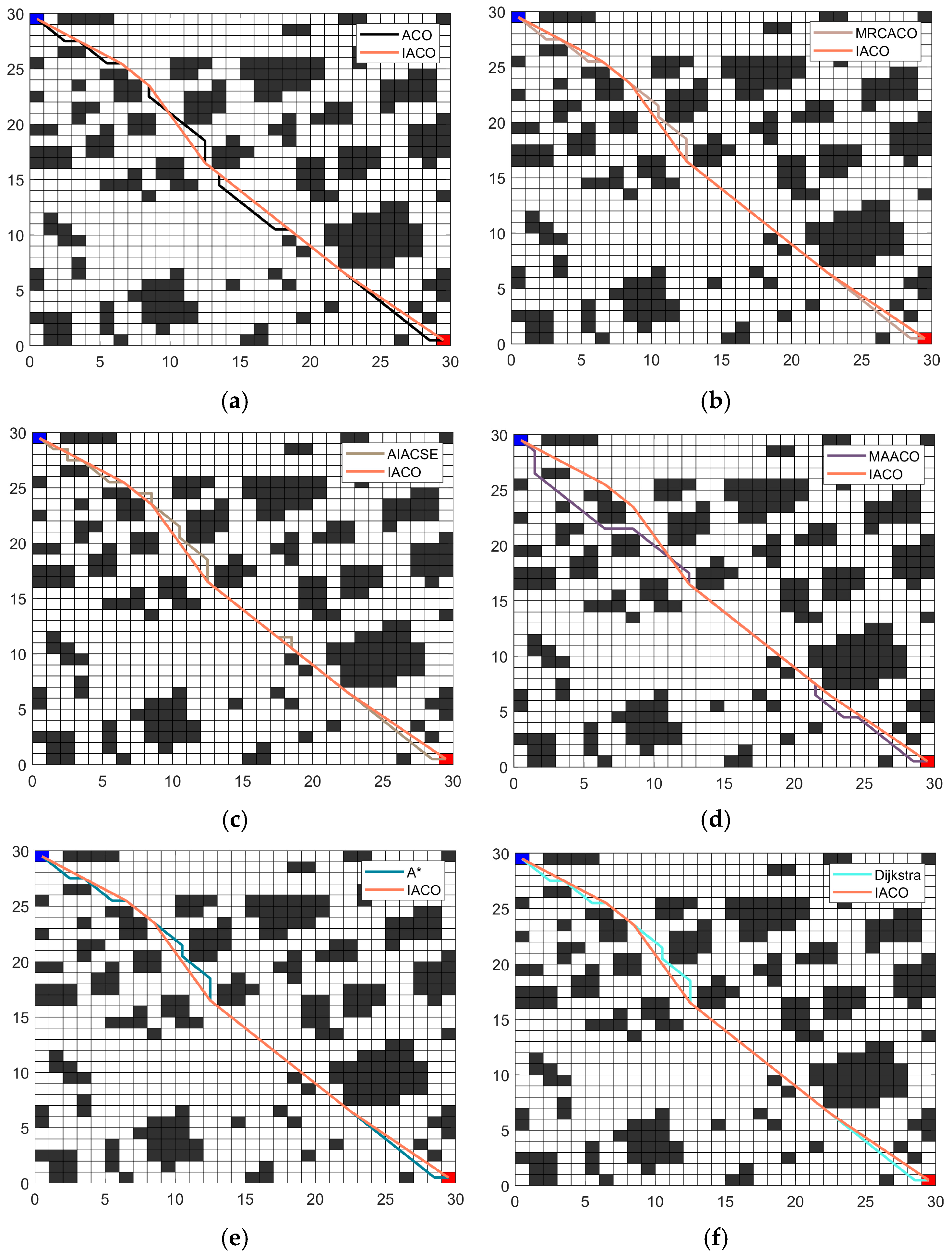

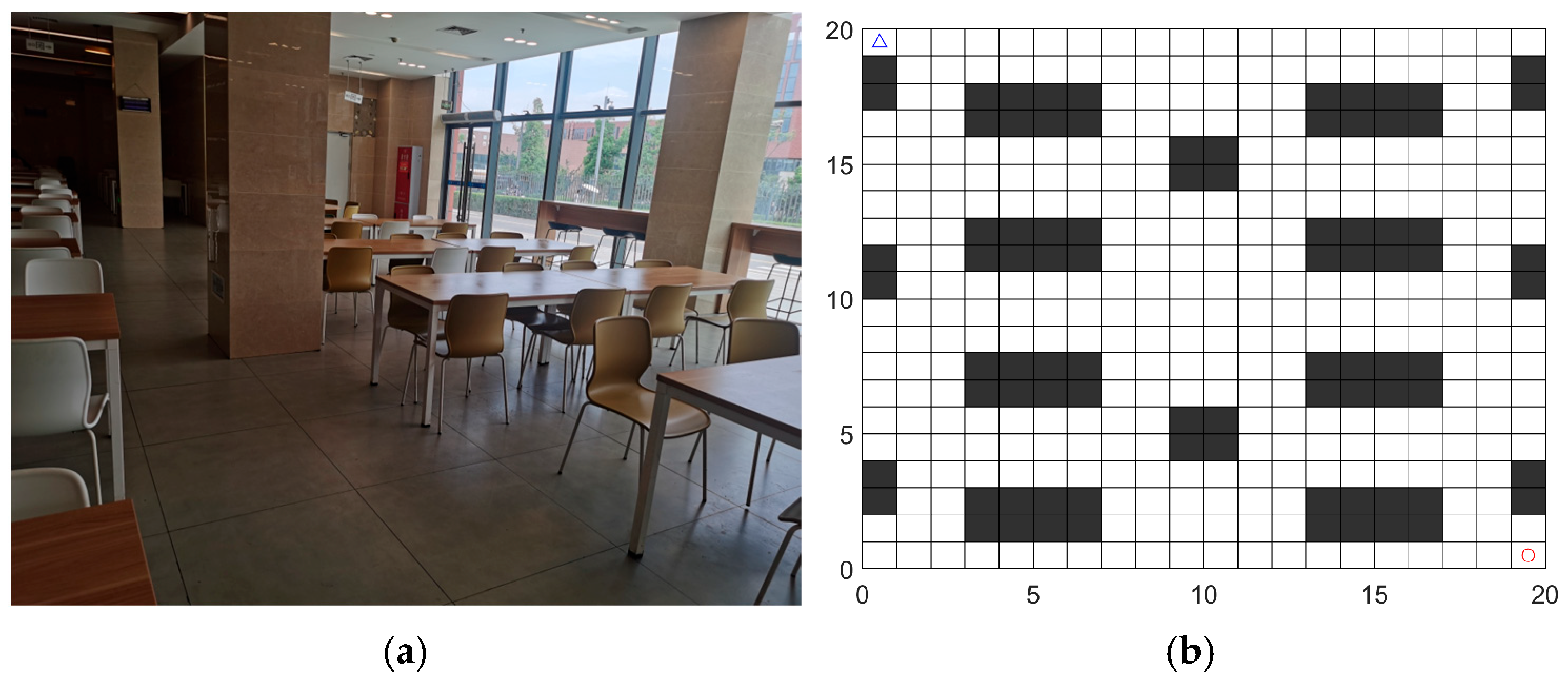

Experimental verification was conducted on both the IACO and the fusion algorithm. Simulation experiments demonstrated that the IACO exhibits superior advantages in path length, smoothness, and convergence time. In obstacle avoidance experiments, the fusion algorithm effectively achieves obstacle avoidance planning.

The content of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 introduces the fundamental theory of traditional ACO and IACO algorithms.

Section 3 describes enhancements to the DWA and the overall rules for the hybrid algorithm.

Section 4 details simulation experiments and result analysis.

Section 5 presents the conclusions.

3. Fusion Path Planning Algorithm

3.1. Dynamic Window Approach for Local Path Planning

The DWA is a common local path planning algorithm. Its principle involves generating multiple predicted trajectories by selecting velocity combinations in the velocity sampling space, then scoring each trajectory. It determines the optimal trajectory and corresponding velocity combination for the robot at the current time step. The resulting velocity and angular velocity combinations are provided to the respective robot as control parameters. Due to limitations in global path planning capability, DWA is generally combined with global path planning algorithms. This combination enables the delivery robot to possess not only global path planning but also local dynamic obstacle avoidance capabilities.

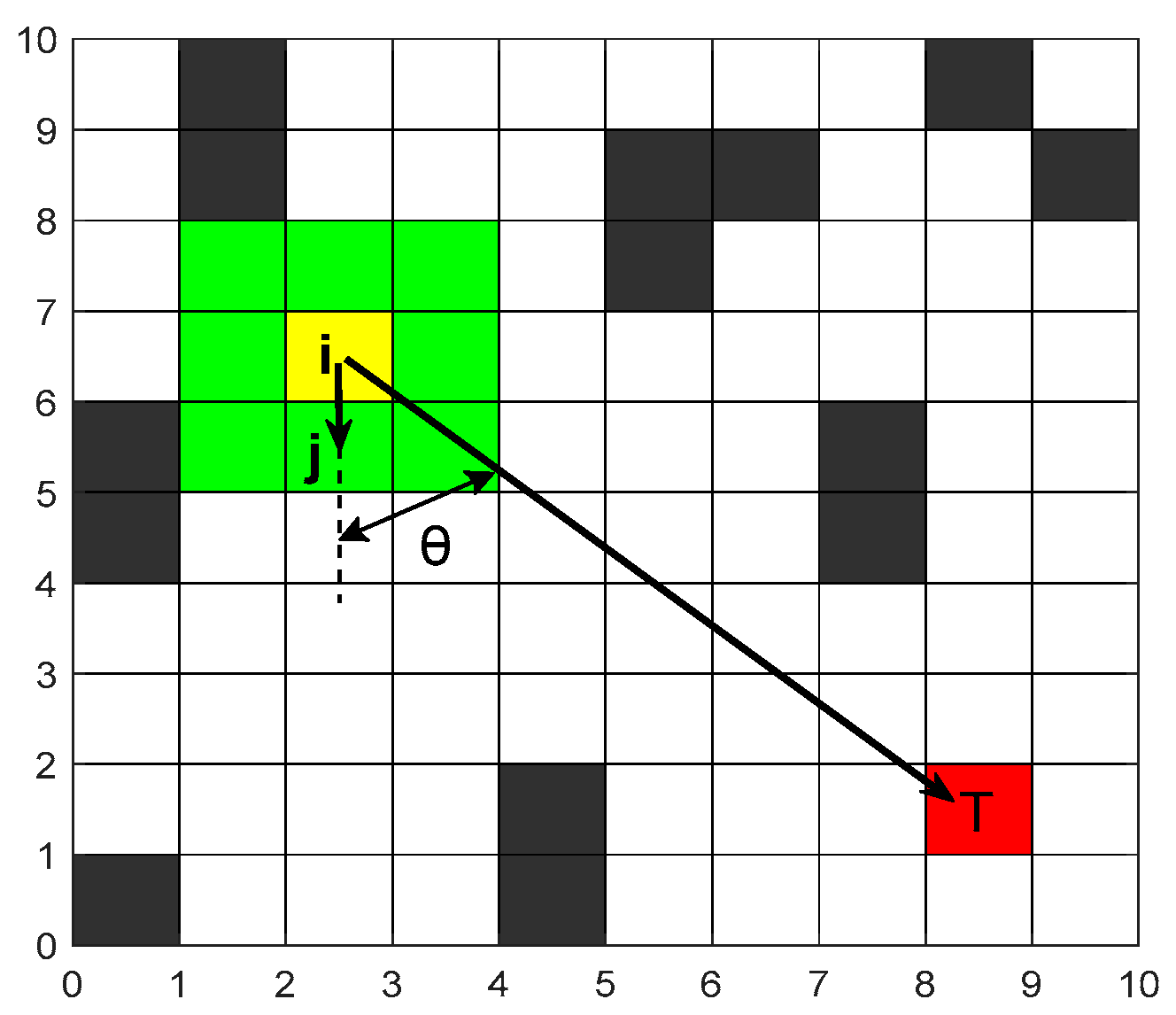

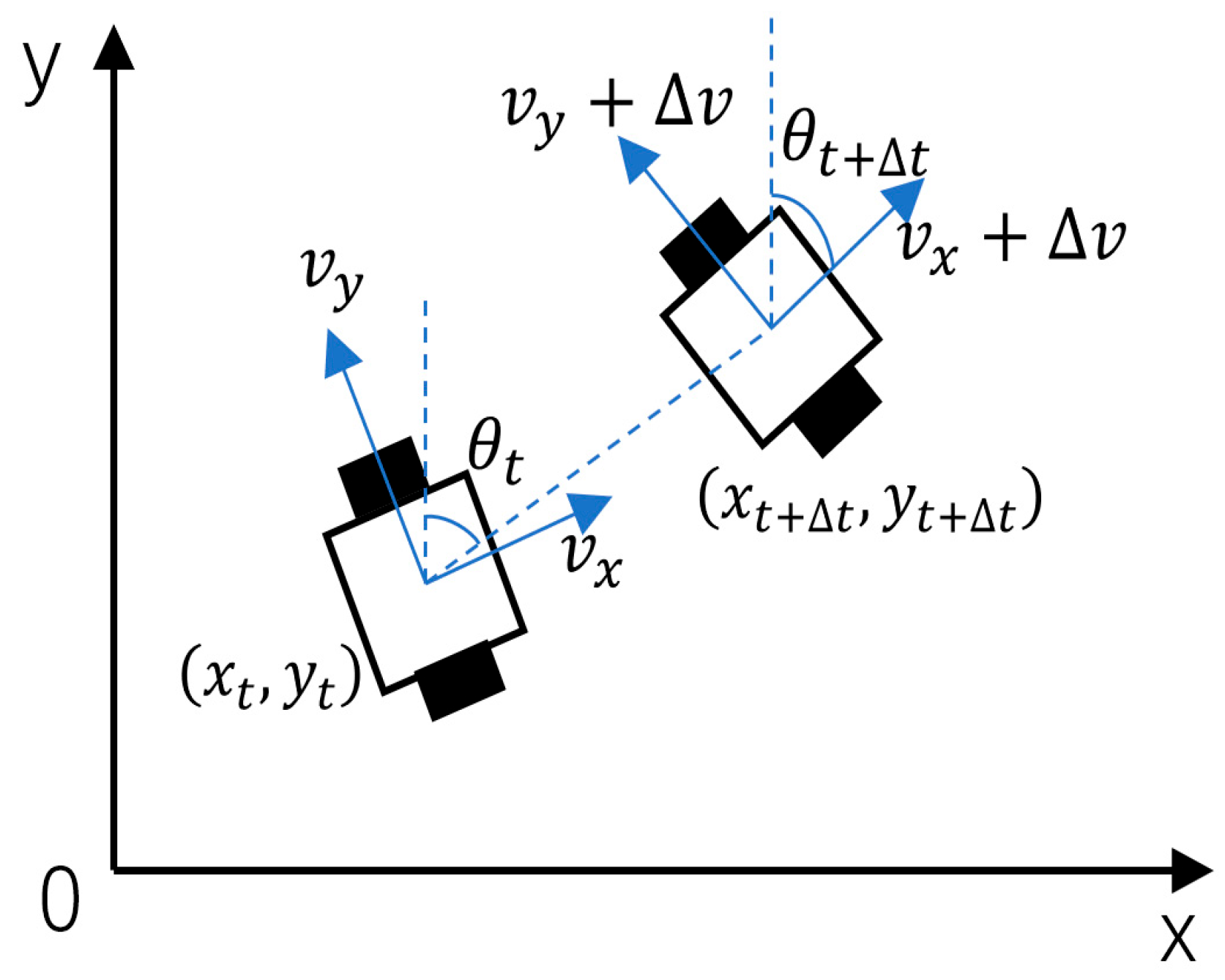

3.1.1. Establishment of a Robot Motion Model

The DWA algorithm primarily controls motion and determines position information through the robot’s linear velocity, angular velocity, and heading angle. Different kinematic models exist for different robot drive configurations. The robot motion model employed by delivery robots is a two-wheel differential motion model, as shown in

Figure 6.

Assume the robot’s position at time

is

. Over the time interval

, the position increment is given by Equation (22):

where

denotes the robot’s velocity at time

, and

denotes the robot’s angular velocity at time

.

3.1.2. Establish a Speed Zone

After establishing the robot’s motion trajectory space, the velocity space must be defined. Within this defined velocity space, multiple velocity combinations are sampled at a specified resolution. Based on these sampled velocity combinations, multiple corresponding motion trajectories are simulated over a defined time period. These trajectories will be evaluated by the evaluation function to determine relatively optimal velocity combinations. The velocity space represents the robot’s speed range, constrained by factors associated with the delivery robot’s performance capabilities and environmental conditions, ultimately limiting it to a specific velocity range.

- (1)

Constrained by its maximum and minimum speeds, the delivery robot can reach a speed of .

In Equation (23), and denote the minimum and maximum linear velocities achievable by the delivery robot, respectively; and denote the minimum and maximum angular velocities achievable by the delivery robot, respectively.

- (2)

Constrained by motor performance, the delivery robot can achieve a speed of .

In Equation (24), and denote the linear velocity and angular velocity at the current time; and represent the maximum acceleration and maximum deceleration achievable in linear velocity under motor performance; and denote the maximum acceleration and maximum deceleration achievable in angular velocity under motor performance.

- (3)

Constrained by obstacles, the delivery robot can achieve a speed of .

In Equation (25), denotes the distance between the simulation trajectory corresponding to and the nearest obstacle.

Taking the intersection of the above constraints yields the robot’s feasible velocity space, with the velocity range given by Equation (26):

3.1.3. Optimization of the Evaluation Function

After sampling the velocity space, multiple predicted trajectories can be obtained based on the established robot motion model. At this point, these trajectories must be evaluated to select the optimal motion path, i.e., the optimal velocity combination. The evaluation function for the traditional DWA is shown in Equation (27):

where

denotes the heading evaluation function, which assesses the angular difference between the predicted trajectory endpoint orientation and the target point at the current sampled velocity in velocity space;

is the distance evaluation function, representing the distance between the estimated trajectory endpoint and the nearest obstacle;

is the velocity evaluation function, representing the robot’s current linear velocity; a, b, and c are weighting coefficients.

To enhance the robot’s capability to avoid dynamic obstacles, dynamic obstacles are initially identified by comparing the obstacle’s position at the current time step with its position at the next time step. If the obstacle is determined to be dynamic, dynamic obstacle avoidance rules are applied. If the obstacle is static, static obstacle avoidance rules are applied. The distance evaluation subfunction is optimized within the evaluation function, specifically:

In Equation (28),

denotes the nearest distance between the endpoint of the predicted trajectory and static obstacles;

denotes the nearest distance between the endpoint of the predicted trajectory and dynamic obstacles;

represents the displacement of dynamic obstacles, as shown in Equation (29).

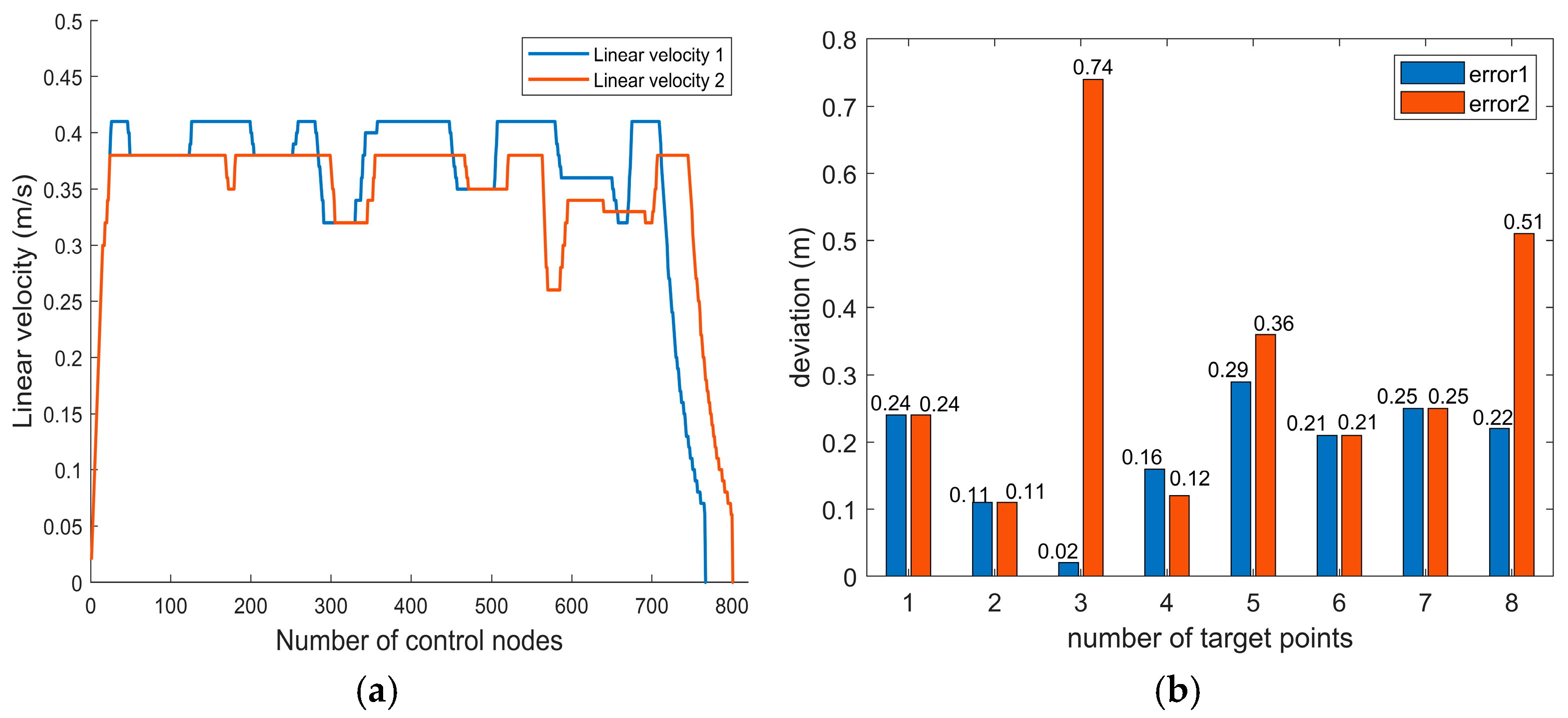

When robots operate in areas with numerous obstacles, fluctuations in linear velocity become more frequent and pronounced, leading to reduced operational efficiency and unnecessary motor wear. Therefore, introducing a linear velocity variation sub-evaluation function into the assessment function, namely

In Equation (30), denotes the linear velocity change evaluation function; represents the linear velocity at the robot’s current position; denotes the linear velocity at the end of the predicted trajectory.

To ensure that the robot can better approach the global path and obtain a smoother path during its movement, a path proximity evaluation subfunction is introduced into the evaluation function, namely:

In Equation (31), denotes the position at the end of the predicted trajectory, represents the previous path key node, and denotes the subsequent path key node.

Finally, the improved evaluation function is given by Equation (32):

where

denotes the weight parameter for the linear velocity change assessment function;

denotes the weight parameter for the path proximity assessment function.

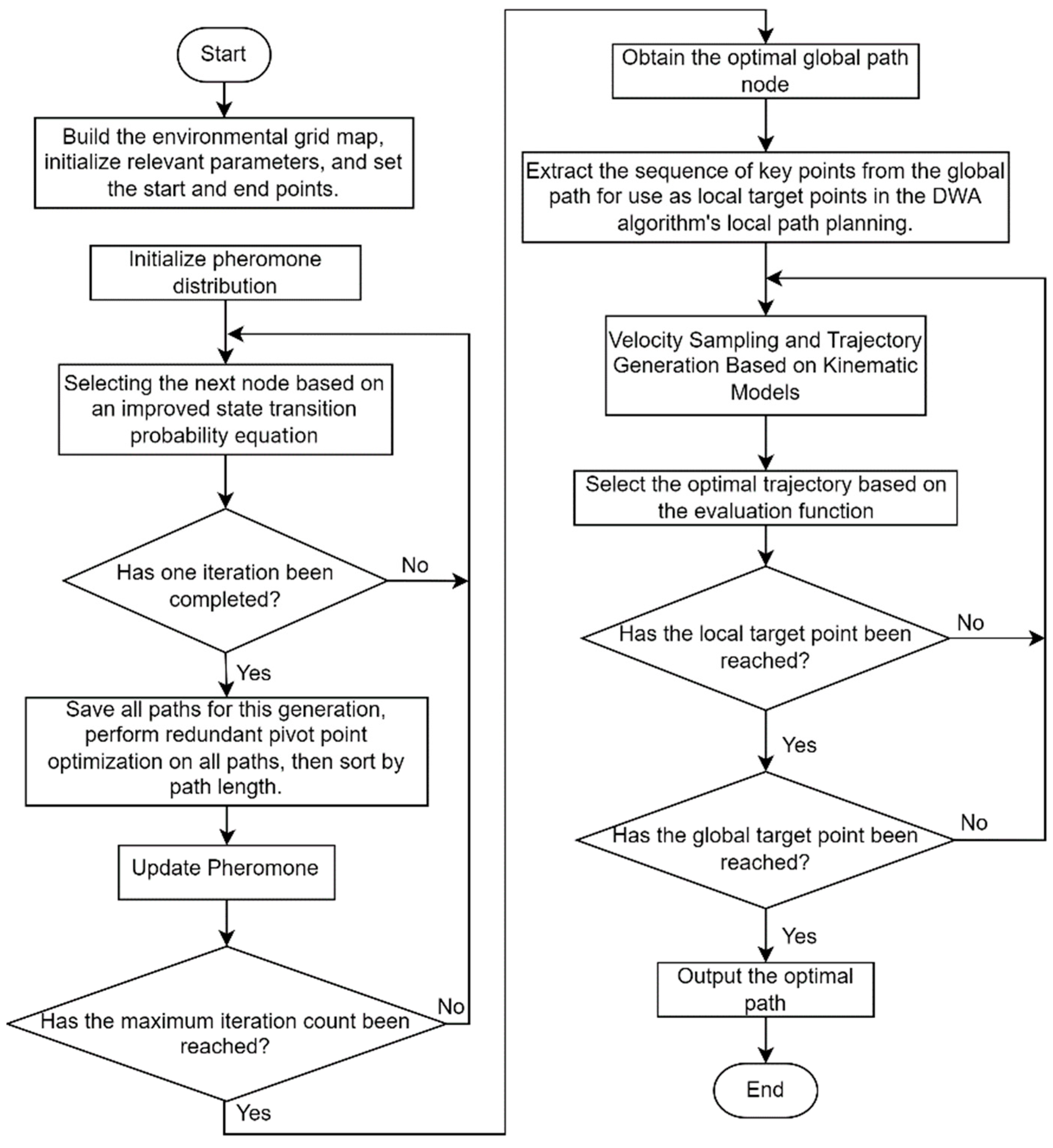

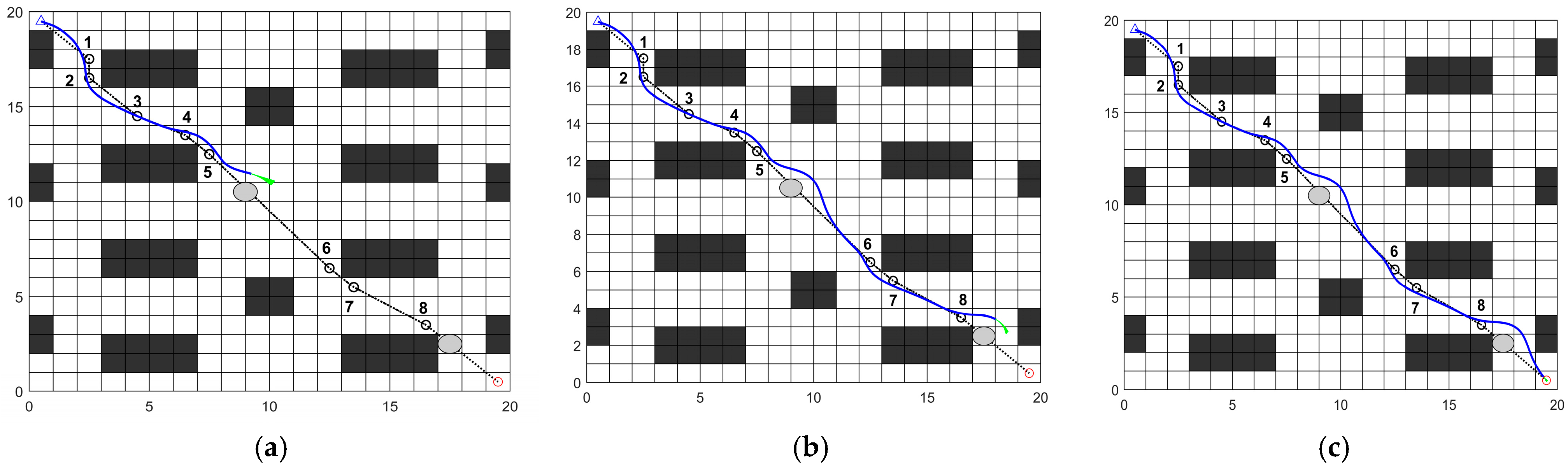

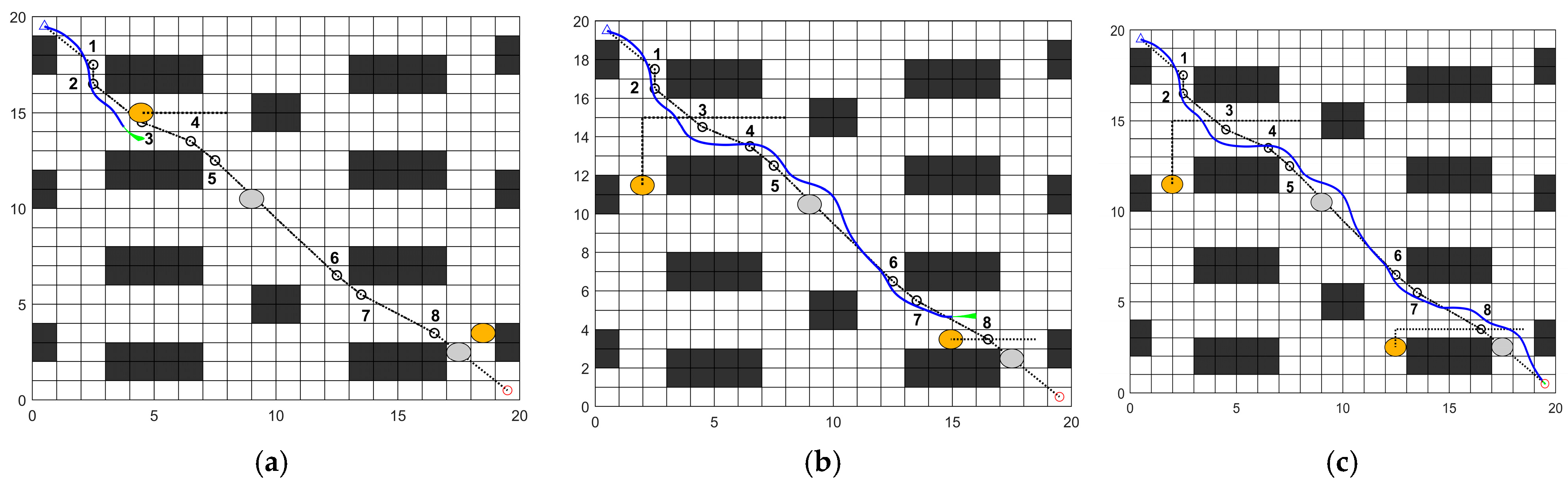

3.2. Dynamic Path Planning Algorithm Fusion

In traditional DWA, the problem often gets stuck in local optima. While IACO can achieve optimal solutions for global path planning in static environments, it lacks obstacle avoidance capabilities in complex environments with dynamic obstacles. To address this issue, the global path generated by the IACO is introduced as a guidance target for local dynamic planning.

By integrating the IACO with the enhanced DWA, the path turning points gained from the IACO serve as the required local sub-goal points for DWA. DWA performs segmented path planning using these sub-goal points to attain obstacle avoidance for the robot. The fusion algorithm enables globally optimal dynamic path planning and real-time obstacle avoidance. The path planning process of the fusion algorithm is illustrated in

Figure 7.

The specific implementation steps are as follows:

Step 1: Create an environmental map by establishing the robot’s working environment using a grid map, and set the robot’s starting point and destination.

Step 2: Initialize relevant parameters such as ant population size, maximum iteration count, and various importance factors; initialize the initial pheromones on the map.

Step 3: Employ the IACO for global path planning to obtain a globally optimal path, and extract the sequence of key nodes along the path.

Step 4: Perform velocity sampling and generate predicted trajectories based on the robot’s kinematic model.

Step 5: According to the key nodes of the extracted path and the generated predicted trajectory, evaluate using the improved assessment function and select the optimal speed control as the output.

Step 6: Determine whether a local target point has been reached. If reached, select the next node as the new local target point and execute Step 4. If not reached, return to Step 4 to continue iteration.

Step 7: Determine whether the global target point has been reached. If the global target point has not been reached, return to step 6. If the global target point has been reached, terminate the loop.

5. Conclusions

Robot navigation relies heavily on path planning, hence studying path planning algorithms is necessary. This paper overcomes the shortcomings and limitations of traditional ACO and DWA algorithms by optimizing both approaches. It then integrates the IACO and DWA algorithms to improve the overall performance and obstacle avoidance capabilities of the path planning system.

To address the limitations of traditional ACO, the following improvement strategies are proposed: A strategy for initial pheromone distribution based on node positions and obstacle information is introduced. A gravitational mechanism and directional angle heuristic function are adopted as new heuristic information for state transition rules. A new pheromone update rule is implemented that sorts paths by length and adds extra pheromone to paths with optimal lengths. By reducing redundant turning points in global paths, the algorithm optimizes the issue of excessive path turns in traditional ACO, resulting in smoother paths.

To optimize the local path planning performance of the DWA, this study enhances its evaluation function to better track the global path while simultaneously improving dynamic obstacle avoidance capabilities. To this end, three evaluation subfunctions have been introduced based on the evaluation function: the dynamic obstacle distance evaluation subfunction, the linear velocity change evaluation subfunction, and the path proximity evaluation subfunction.

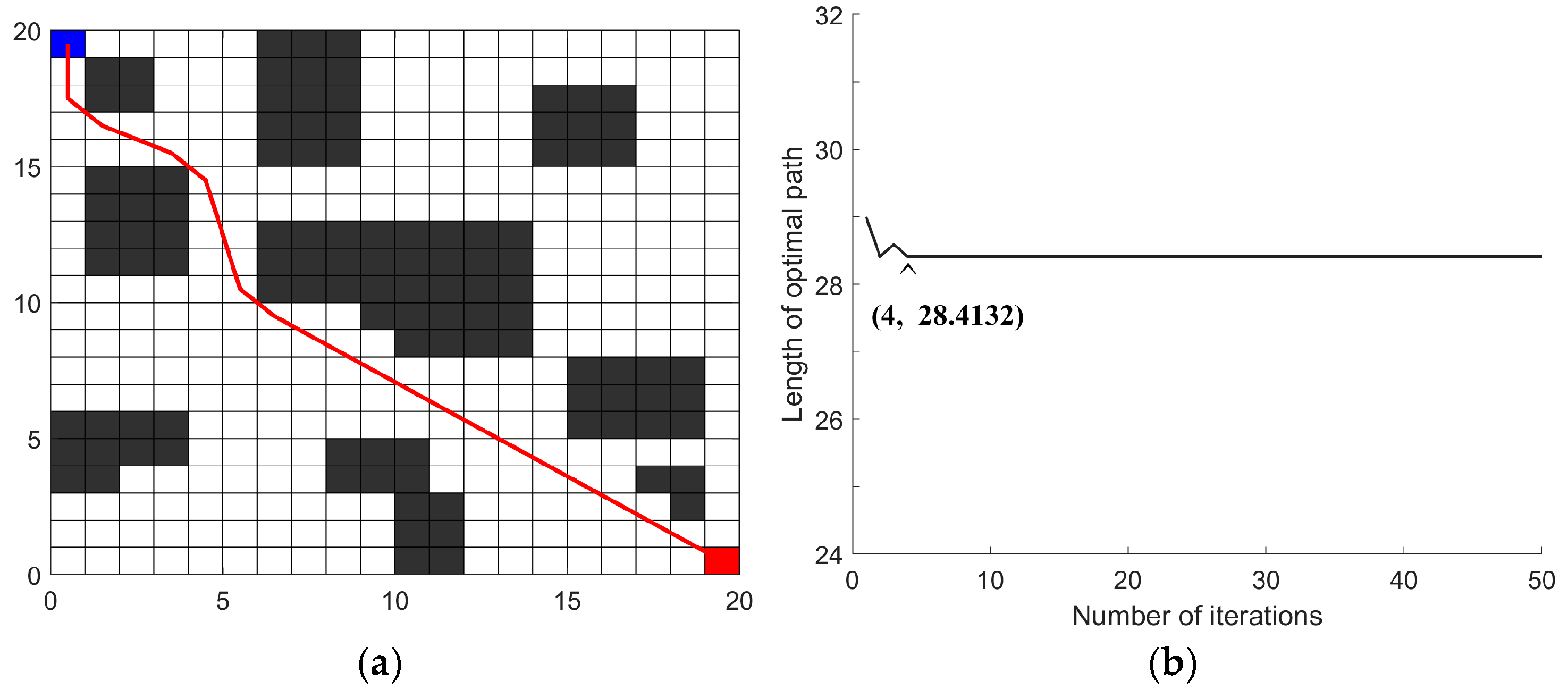

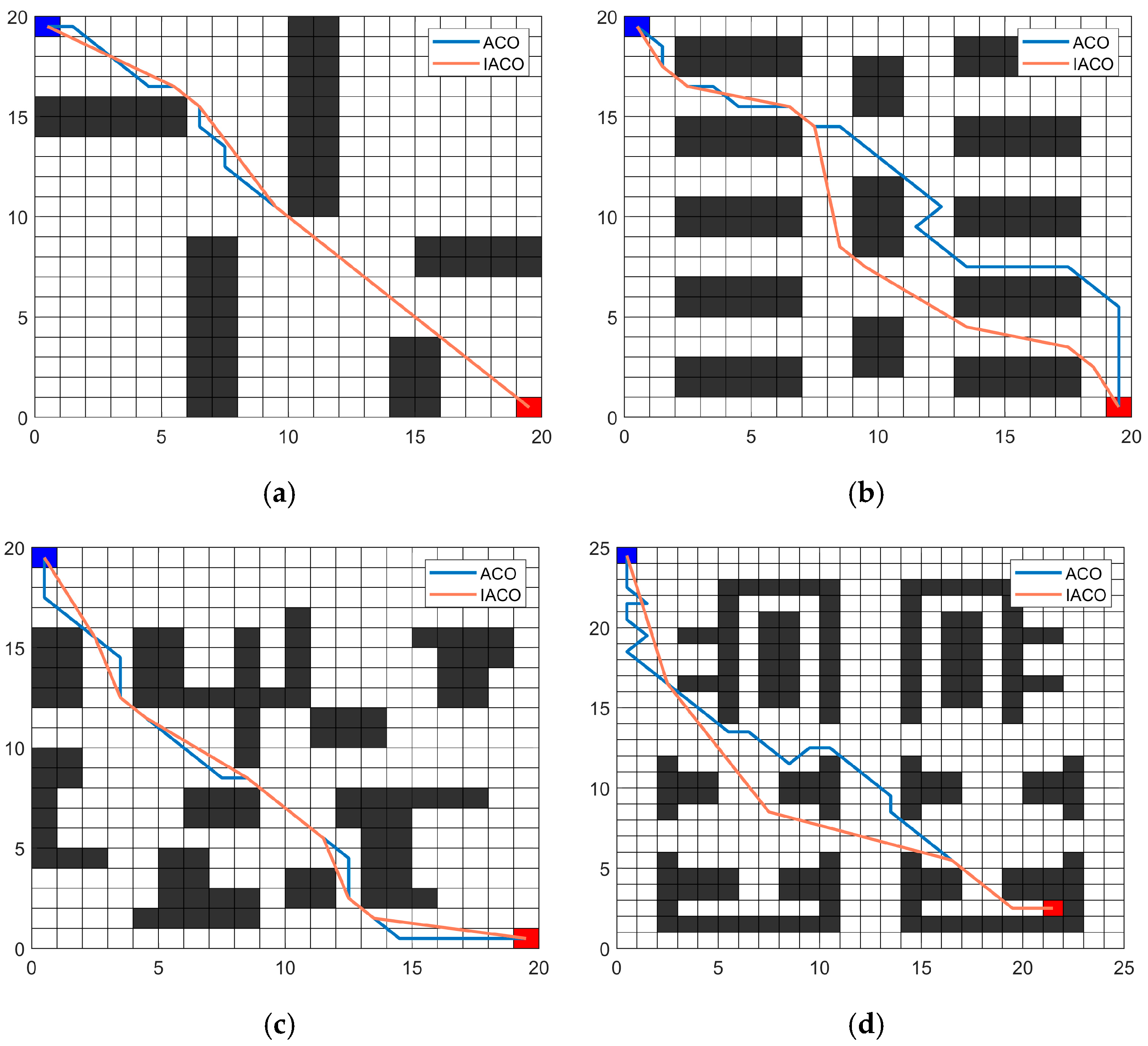

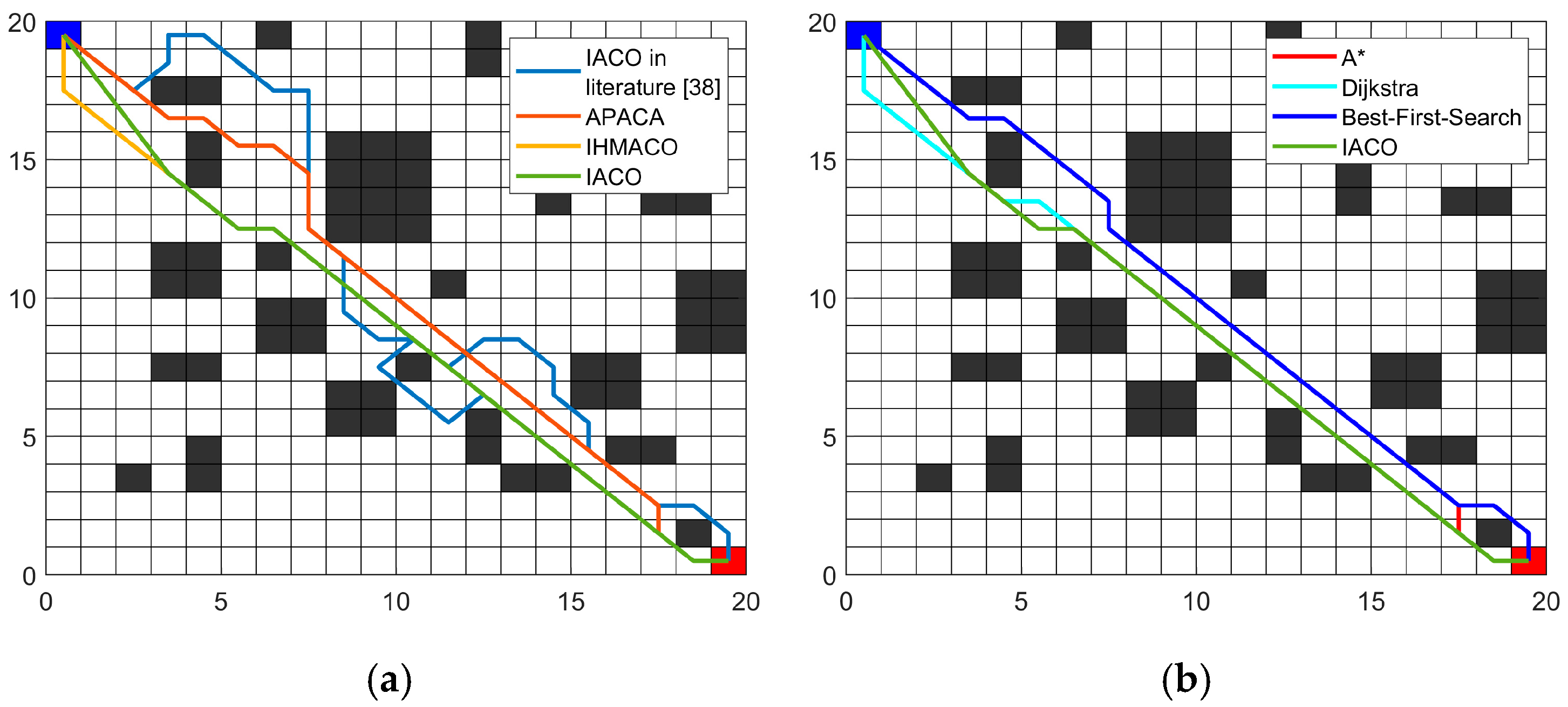

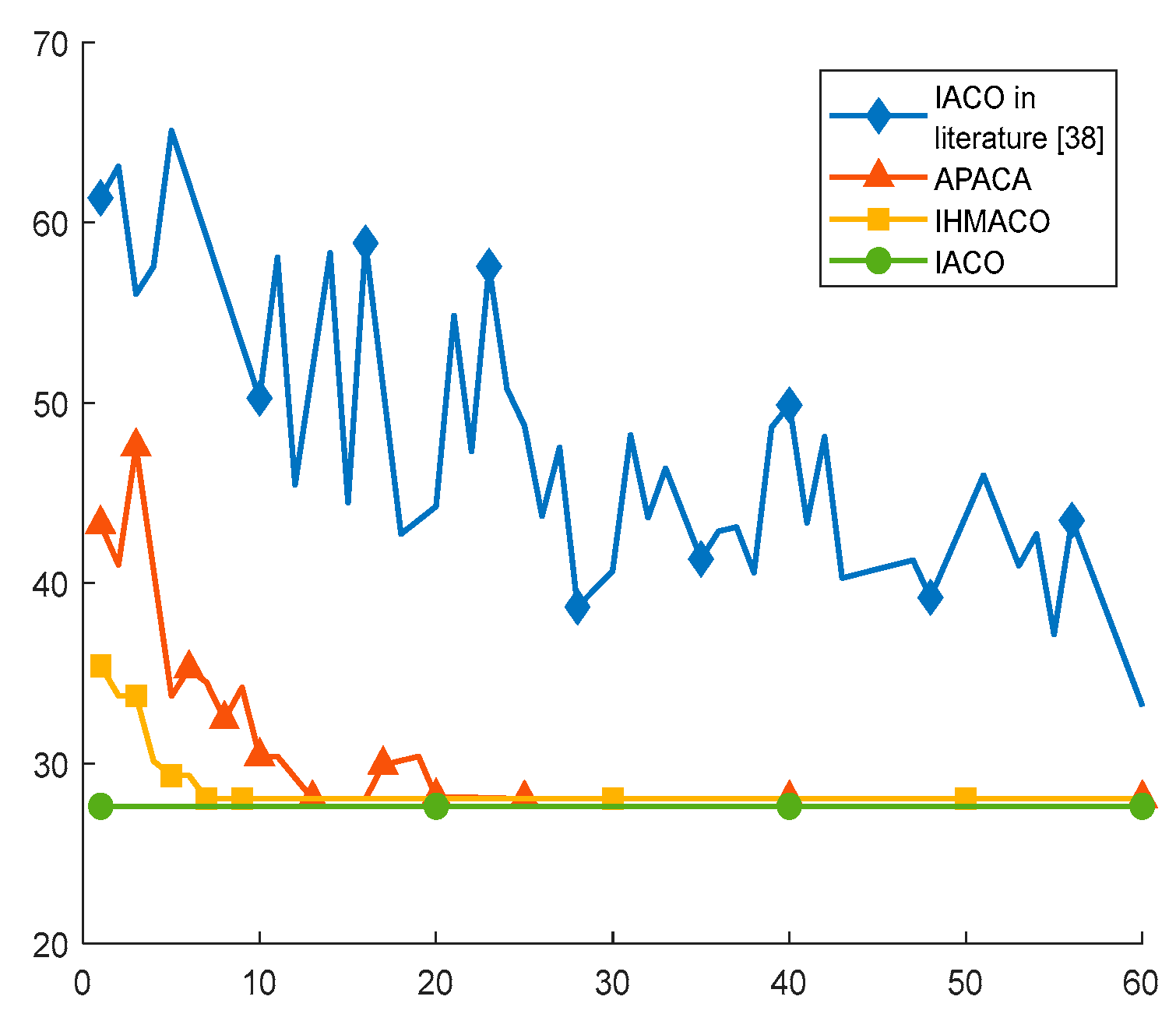

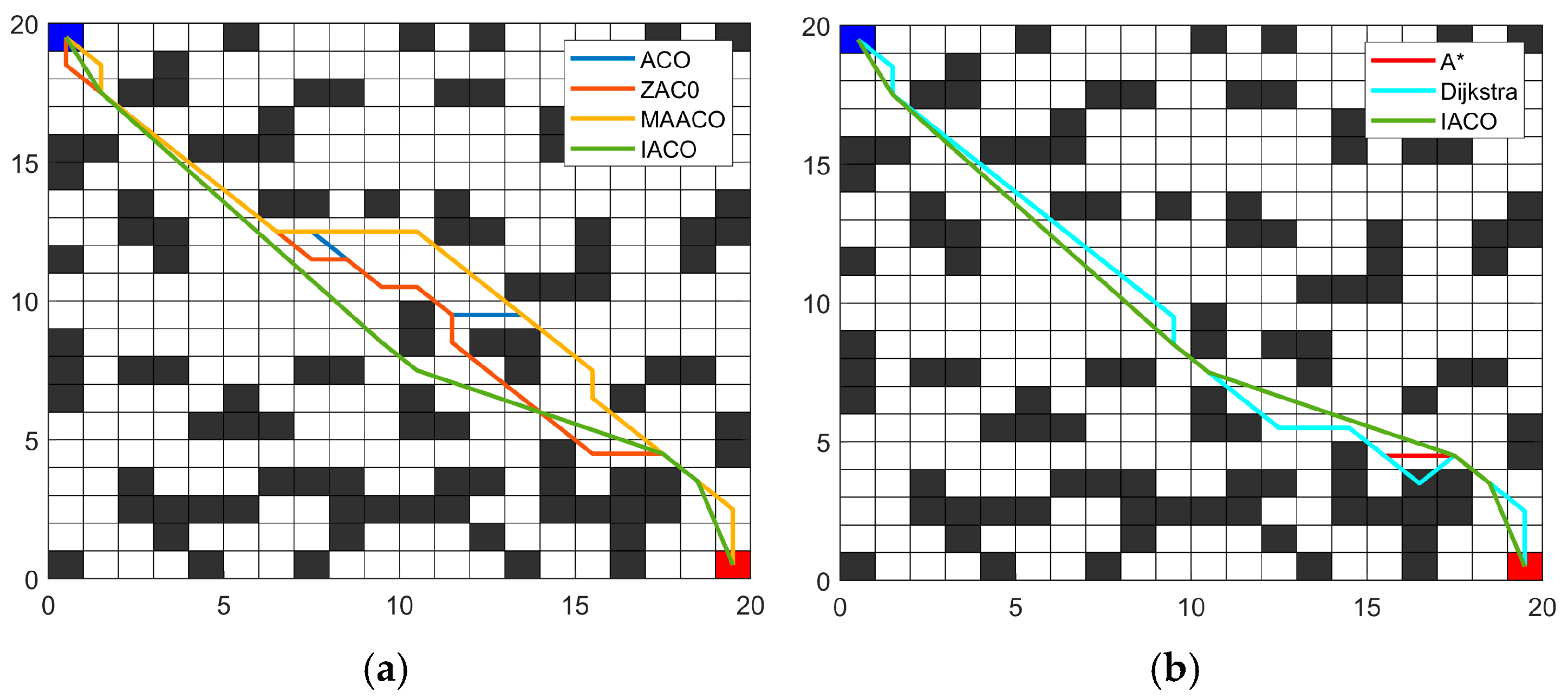

Simulation experiments demonstrate that compared to the traditional ACO across four environments, the IACO decreased the average path length by 13.98%, 17.53%, 20.32%, and 30.03%, respectively. It also decreased the number of path turns by 25%, 41.67%, 25%, and 71.43%, respectively. Comparisons with several other intelligent algorithms further demonstrated that the IACO exhibits superior advantages in path length, smoothness, and convergence iterations. Finally, the integration of the IACO and DWA algorithms enabled the fusion algorithm to effectively plan optimal paths and execute superior obstacle avoidance strategies in both static and dynamic obstacle avoidance experiments.