Plyometric Performance in Under-10 Soccer Players: Effects of Modified Competitions and Maturational Status

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistics

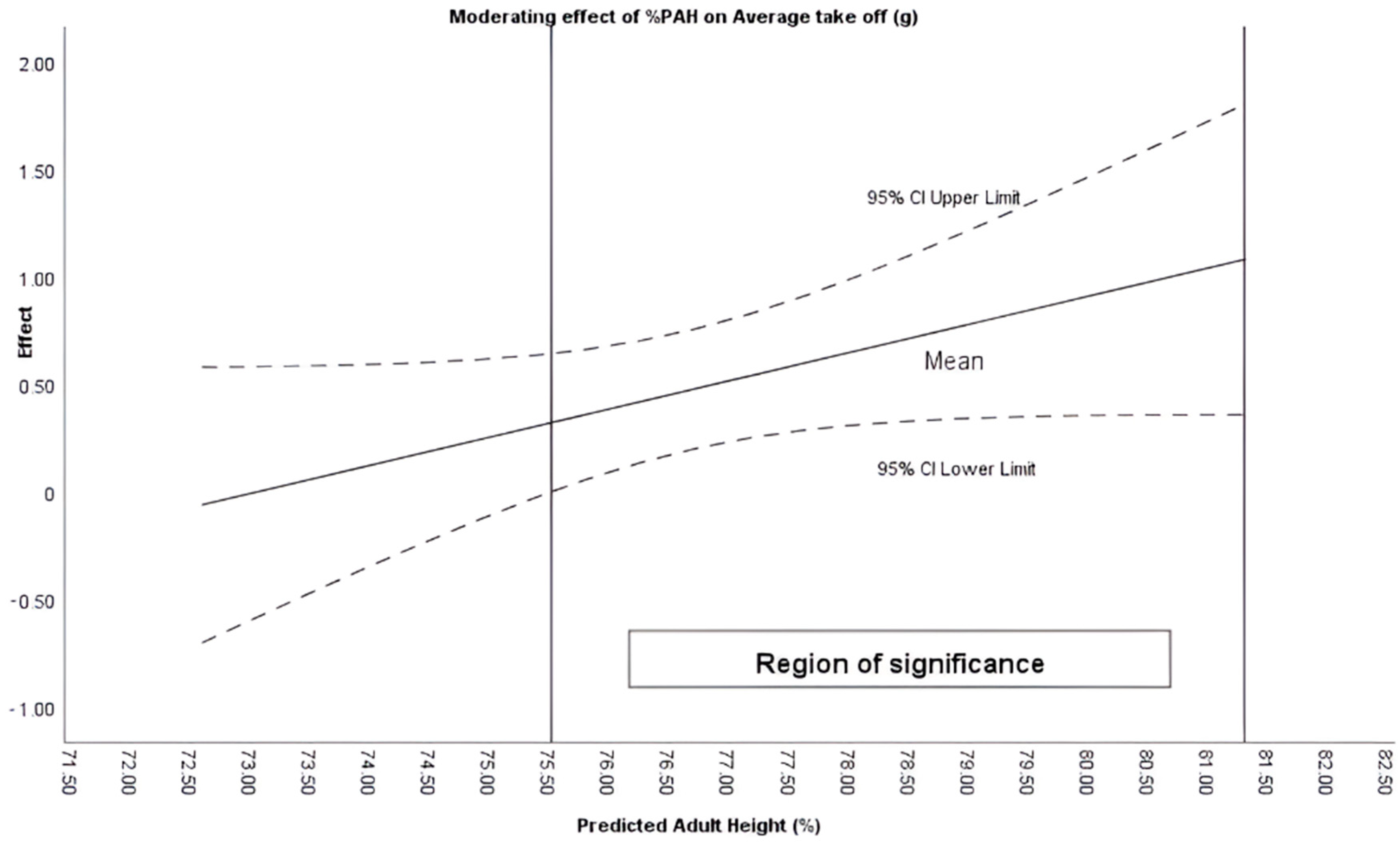

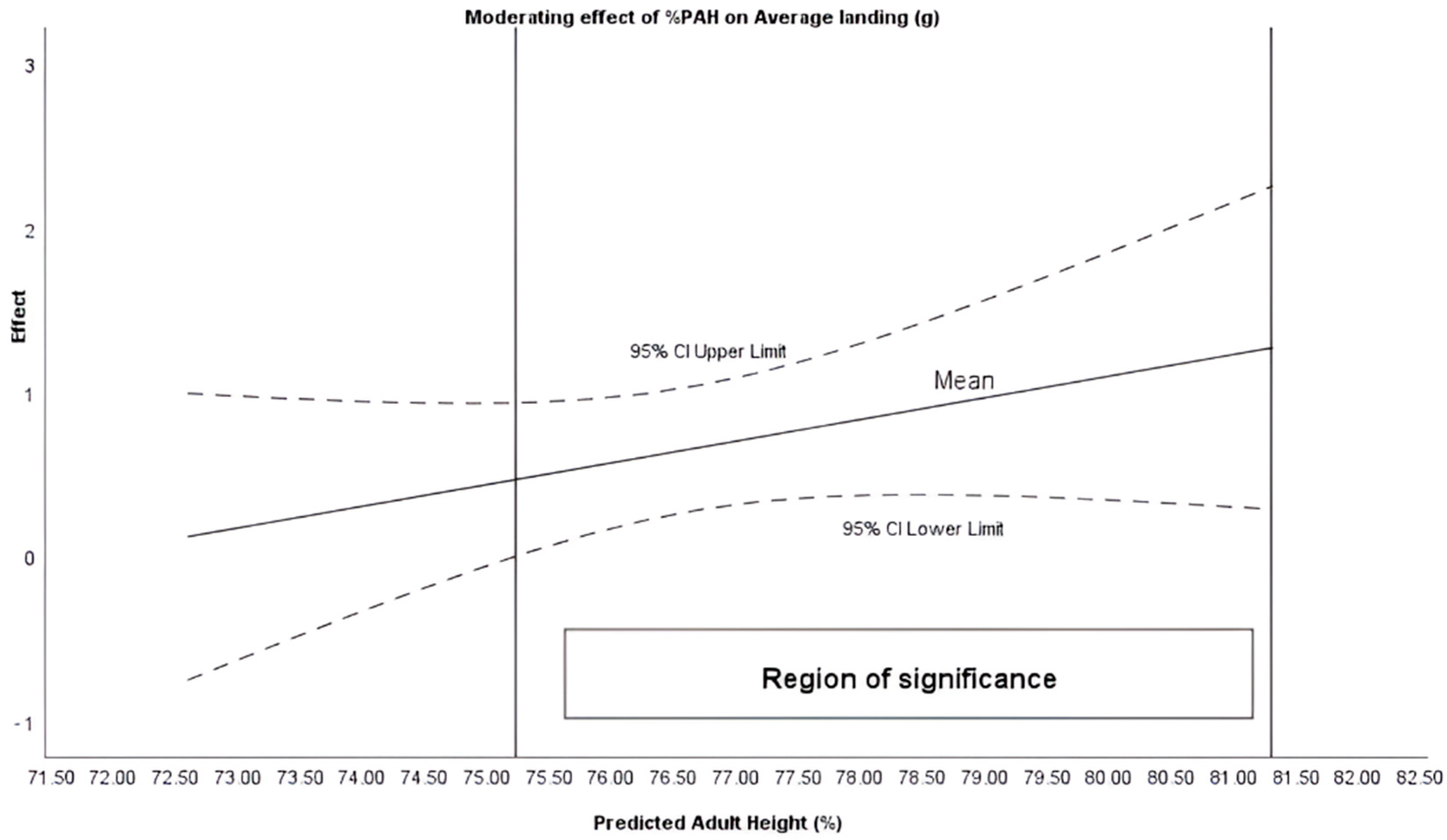

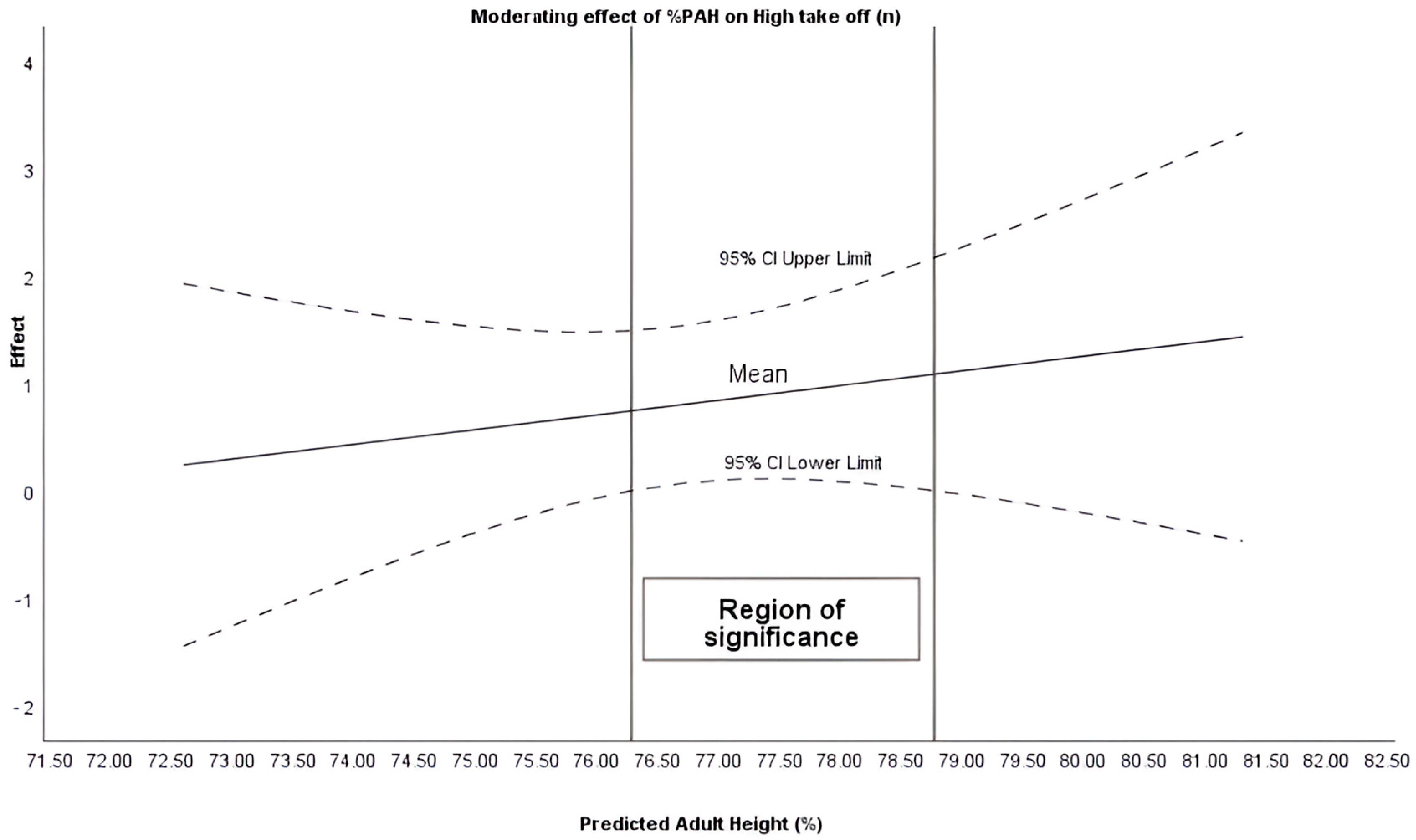

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asadi, A.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Arazi, H.; Sáez de Villarreal, E. The Effects of Maturation on Jumping Ability and Sprint Adaptations to Plyometric Training in Youth Soccer Players. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 2405–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruitenberg, M.F.L.; Abrahamse, E.L.; Verwey, W.B. Sequential Motor Skill in Preadolescent Children: The Development of Automaticity. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 2013, 115, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Assaoka, T.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Alvarez, C.; Garcia-Pinillos, F.; Moran, J.; Gentil, P.; Behm, D. Effects of Maturation on Physical Fitness Adaptations to Plyometric Drop Jump Training in Male Youth Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 2760–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jávega, G.; Javaloyes, A.; Moya-Ramón, M.; Peña-González, I. Influence of Biological Maturation on Training Load and Physical Performance Adaptations After a Running-Based HIIT Program in Youth Football. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Chen, J.; Yan, R.; Deng, B.; Song, W.; Guan, B.; Sun, J. Effects of Maturation Stage on Physical Fitness in Youth Male Team Sports Players After Plyometric Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Open 2025, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wik, E.H. Growth, Maturation and Injuries in High-Level Youth Football (Soccer): A Mini Review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 975900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonito, F.P.; Emmonds, S.; Teles, J.; Keshtkarhesamabadi, B.; Moura, F.; Coelho-e-Silva, M.J.; Fragoso, M.I.G. Growth and Maturation in Youth Female Football Players and Its Association with Body Composition and Physical Performance: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Sports. Sci. Coach. 2025, 17479541251380020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.F.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Ceylan, H.İ.; Sarmento, H.; Clemente, F.M. Effects of Maturation Stage on Sprinting Speed Adaptations to Plyometric Jump Training in Youth Male Team Sports Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2022, 13, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.M.; Williams, S.; Bradley, B.; Sayer, S.; Murray Fisher, J.; Cumming, S. Growing Pains: Maturity Associated Variation in Injury Risk in Academy Football. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2020, 20, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Angulo, F.J.; Palao, J.M.; Gimdénez-Egido, J.M.; Ortega-Toro, E. Effect of Rule Modifications on Kinematic Parameters Using Maturity Stage as a Moderating Variable in U-10 Football Players. Sensors 2024, 24, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, S.P.; Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L.; Eisenmann, J.C.; Malina, R.M. Bio-Banding in Sport: Applications to Competition, Talent Identification, and Strength and Conditioning of Youth Athletes. Strength Cond. J. 2017, 39, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malina, R.M.; Cumming, S.P.; Rogol, A.D.; Coelho-e-Silva, M.J.; Figueiredo, A.J.; Konarski, J.M.; Kozieł, S.M. Bio-Banding in Youth Sports: Background, Concept, and Application. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1671–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbett, T.J.; Whyte, D.G.; Hartwig, T.B.; Wescombe, H.; Naughton, G.A. The Relationship Between Workloads, Physical Performance, Injury and Illness in Adolescent Male Football Players. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.-Y.; Wang, X.; Hao, L.; Ran, X.-W.; Wei, W. Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Plyometric Training on the Athletic Performance of Youth Basketball Players. Front. Physiol 2024, 15, 1427291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.; Brito, J.; Seabra, A.; Oliveira, J.; Krustrup, P. Physical Match Performance of Youth Football Players in Relation to Physical Capacity. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2014, 14, S148–S156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Castillo, D.; Raya-González, J.; Moran, J.; de Villarreal, E.S.; Lloyd, R.S. Effects of Plyometric Jump Training on Jump and Sprint Performance in Young Male Soccer Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 2125–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, A.; Arazi, H.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Moran, J.; Izquierdo, M. Influence of Maturation Stage on Agility Performance Gains After Plyometric Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 2609–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, G.; Mikulic, P. Neuro-Musculoskeletal and Performance Adaptations to Lower-Extremity Plyometric Training. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 859–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, H.; Quan, W.; Ma, X.; Chon, T.; Fernandez, J.; Gusztav, F.; Kovács, A.; Baker, J.; Gu, Y. New Insights Optimize Landing Strategies to Reduce Lower Limb Injury Risk. Cyborg. Bionic. Syst. 2024, 5, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arede, J.; Cumming, S.; Johnson, D.; Leite, N. The Effects of Maturity Matched and Un-Matched Opposition on Physical Performance and Spatial Exploration Behavior during Youth Basketball Matches. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Pipó, J.; de Sousa Pinheiro, G.; Pombal, D.F.; Toscano, L.M.; Llamas, J.E.; Gallardo, J.M.; Requena, B.; Mariscal-Arcas, M. Investigating Acceleration and Deceleration Patterns in Elite Youth Football: The Interplay of Ball Possession and Tactical Behavior. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, D.; Thorpe, R. A Model for the Teaching of Games in Secondary Schools. Bull. Phys. Educ. 1982, 18, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, L.; Brooker, R.; Patton, K. Teaching Games for Understanding: Theory, Research, and Practice; Human Kinetics: Champaign IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bedoya, A.A.; Miltenberger, M.R.; Lopez, R.M. Plyometric Training Effects on Athletic Performance in Youth Soccer Athletes: A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2351–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronnestad, B.R.; Kvamme, N.H.; Sunde, A.; Raastad, T. Short-Term Effects of Strength and Plyometric Training on Sprint and Jump Performance in Professional Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Moraleda, B.; Nedergaard, N.J.; Morencos, E.; Casamichana, D.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Vanrenterghem, J. External and Internal Loads during the Competitive Season in Professional Female Soccer Players According to Their Playing Position: Differences between Training and Competition. Res. Sports Med. 2021, 29, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.; Brickley, G.; Smeeton, N.J. Positional Differences in GPS Outputs and Perceived Exertion During Soccer Training Games and Competition. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 3222–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, H.J.; Roche, A.F. Predicting Adult Stature without Using Skeletal Age: The Khamis-Roche Method. Pediatrics 1994, 94, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.K. Moderation Analysis in Two-Instance Repeated Measures Designs: Probing Methods and Multiple Moderator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, T.G.A.; de Ruiter, C.J.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Savelsbergh, G.J.P.; Beek, P.J. Quantification of In-Season Training Load Relative to Match Load in Professional Dutch Eredivisie Football Players. Sci. Med. Footb. 2017, 1, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrento-Aguiar, R.A.; García-Angulo, F.J.; Leonardo, L.; Palao-Andrés, J.M.; Ortega-Toro, E. Impact of Modified Competition Formats on Physical Performance in Under-14 Female Volleyball Players: The Role of Biological Maturity. Sports 2025, 13, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrento-Aguiar, R.A.; Arede, J.; Leite, N.; García-Angulo, F.J.; Pino-Ortega, J.; Ortega-Toro, E. Influence of Two Different Competition Models on Physical Performance in Under-13 Basketball Players: Analysis Considering Maturity Timing. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Angulo, A.; García-Angulo, F.J.; Torres-Luque, G.; Ortega-Toro, E. Applying the New Teaching Methodologies in Youth Football Players: Toward a Healthier Sport. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halouani, J.; Chtourou, H.; Dellal, A.; Chaouachi, A.; Chamari, K. Soccer Small-Sided Games in Young Players: Rule Modification to Induce Higher Physiological Responses. Biol. Sport 2017, 34, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buszard, T.; Reid, M.; Masters, R.; Farrow, D. Scaling the Equipment and Play Area in Children’s Sport to Improve Motor Skill Acquisition: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, K.; Araújo, D.; Correia, V.; Vilar, L. How Small-Sided and Conditioned Games Enhance Acquisition of Movement and Decision-Making Skills. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2013, 41, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buszard, T.; Garofolini, A.; Reid, M.; Farrow, D.; Oppici, L.; Whiteside, D. Scaling Sports Equipment for Children Promotes Functional Movement Variability. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersmann, F.; Charcharis, G.; Bohm, S.; Arampatzis, A. Muscle and Tendon Adaptation in Adolescence: Elite Volleyball Athletes Compared to Untrained Boys and Girls. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radnor, J.M.; Oliver, J.L.; Waugh, C.M.; Myer, G.; Moore, I.; Lloyd, R. The Influence of Growth and Maturation on Stretch-Shortening Cycle Function in Youth. Sports Med. 2017, 48, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatman, C.E.; Ford, K.R.; Myer, G.D.; Hewett, T.E. Maturation leads to gender differences in landing force and vertical jump performance: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2006, 34, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, W.; Williams, S.; Brickley, G.; Smeeton, N.J. Effects of Bio-Banding upon Physical and Technical Performance during Soccer Competition: A Preliminary Analysis. Sports 2019, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ST | MD1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 2 × 25 min | 5 × 10 min |

| Score | Totals goals | Sets won |

| Substitutions | Free | None (except 5th set) |

| Special rules | The goalkeeper must play at least one period as an outfield player. | |

| Direct headers are prohibited. | ||

| The distance between defenders and the offside line is increased for goal kicks. |

| ST | MD1 | p-Value | Effect Size | BF10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD [IC 95%] | M ± SD [IC 95%] | |||||

| Total impacts (n) | 13,922.7 ± 5096 [12,452; 15,296] | 15,133.6 ± 4457.2 [13,867; 164,00] | 0.082 | 0.251 | 0.661 | ambiguous |

| High impacts (n) * | 104.5 ± 109.7 [72.5; 134] | 86.6 ± 73.1 [65.8; 107] | 0.658 | 0.073 | 0.304 | ambiguous |

| 0–3 g impacts (n) | 11,926.1 ± 4272.8 [10,701; 13,084] | 13,110.6 ± 3802.9 [12,030; 14,191] | <0.048 | 0.286 | 1.002 | anecdotal |

| 3–5 g impacts (n) * | 1336.5 ± 668.3 [1140; 1514] | 1385.6 ± 594.3 [1217; 1555] | 0.235 | 0.194 | 0.184 | ambiguous |

| 5–8 g impacts (n) * | 555.6 ± 350.4 [454; 650] | 550.8 ± 297.1 [466; 635] | 0.996 | 0.002 | 0.155 | ambiguous |

| >8 g impacts (n) * | 104.5 ± 109.7 [72.5; 134] | 86.6 ± 73.1 [65.8; 107] | 0.658 | 0.073 | 0.304 | ambiguous |

| Total horizontal (n) | 16,828.1 ± 7074.9 [14,752; 18,711] | 17,552 ± 5961 [15,858; 19,246] | 0.388 | 0.123 | 0.220 | ambiguous |

| 0–3 horizontal (n) | 16,286.1 ± 6838 [14,285; 18,109] | 17,053 ± 5810 [15,402; 18,705] | 0.348 | 0.134 | 0.235 | ambiguous |

| 3–5 horizontal (n) * | 440.8 ± 302.4 [350; 520] | 421.2 ± 270.6 [344; 498] | 0.499 | 0.111 | 0.169 | ambiguous |

| 5–8 horizontal (n) * | 86.1 ± 91.4 [59; 110] | 66.6 ± 65.3 [48; 85.1] | 0.313 | 0.194 | 0.402 | ambiguous |

| >8 horizontal (n) * | 15.2 ± 20.2 [9.29; 20.6] | 10.7 ± 14.5 [6.57; 14.8] | 0.253 | 0.194 | 0.405 | ambiguous |

| ST | MD1 | p-Value | Effect Size | BF10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD [IC 95%] | M ± SD [IC 95%] | |||||

| Jumps (n) * | 8.36 ± 5.59 [6.61; 9.79] | 8.24 ± 4.69 [6.91; 9.57] | 0.961 | 0.009 | 0.156 | ambiguous |

| Steps (n) | 6336 ± 2663 [5552; 7043] | 6560 ± 2345 [5893; 7226] | 0.497 | 0.097 | 0.192 | ambiguous |

| Average take off (g) * | 2.22 ± 0.73 [2.01; 2.42] | 1.77 ± 0.74 [1.56; 1.98] | 0.001 | 0.525 | 23.97 | very strong |

| Average landing (g) * | 4.89 ± 1.01 [4.60; 5.16] | 4.21 ± 0.79 [3.98; 4.43] | <0.001 | 0.583 | 70.57 | very strong |

| High take off (n) * | 1.74 ± 2.17 [1.10; 2.32] | 1.12 ± 1.11 [0.82; 1.44] | 0.080 | 0.328 | 0.776 | ambiguous |

| High landing (n) * | 1.72 ± 1.77 [1.19; 2.18] | 1.50 ± 1.55 [1.06; 1.94] | 0.441 | 0.143 | 0.193 | ambiguous |

| 3–5 g landing * | 6.64 ± 4.67 [5.18; 7.84] | 6.74 ± 3.97 [5.61; 7.87] | 0.856 | 0.032 | 0.156 | ambiguous |

| 5–8 g landing * | 1.46 ± 1.53 [1; 1.86] | 1.24 ± 1.38 [0.85; 1.63] | 0.500 | 0.129 | 0.200 | ambiguous |

| <8 g landing * | 0.260 ± 0.56 [0.09; 0.41] | 0.260 ± 0.60 [0.09; 0.43] | 0.888 | 0.004 | 0.154 | ambiguous |

| 0–3 g take off * | 6.62 ± 4.26 [5.28; 7.70] | 7.12 ± 4.53 [5.83; 8.41] | 0.506 | 0.118 | 0.201 | ambiguous |

| 3–5 g take off * | 1.16 ± 1.68 [0.67; 1.61] | 0.78 ± 0.84 [0.54; 1.02] | 0.186 | 0.298 | 0.461 | ambiguous |

| 5–8 take off * | 0.08 ± 0.27 [0.25; 0.73] | 0.04 ± 0.20 [0.12; 0.47] | 0.484 | 0.333 | 0.210 | ambiguous |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

García-Angulo, F.J.; García-Angulo, A.; Birrento-Aguiar, R.A.; Ortega-Toro, E. Plyometric Performance in Under-10 Soccer Players: Effects of Modified Competitions and Maturational Status. Sensors 2026, 26, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010068

García-Angulo FJ, García-Angulo A, Birrento-Aguiar RA, Ortega-Toro E. Plyometric Performance in Under-10 Soccer Players: Effects of Modified Competitions and Maturational Status. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Angulo, Francisco Javier, Antonio García-Angulo, Ricardo André Birrento-Aguiar, and Enrique Ortega-Toro. 2026. "Plyometric Performance in Under-10 Soccer Players: Effects of Modified Competitions and Maturational Status" Sensors 26, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010068

APA StyleGarcía-Angulo, F. J., García-Angulo, A., Birrento-Aguiar, R. A., & Ortega-Toro, E. (2026). Plyometric Performance in Under-10 Soccer Players: Effects of Modified Competitions and Maturational Status. Sensors, 26(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010068