Analysis of Bonding Defects in Cementing Casing Using Attenuation Characteristic of Circumferential SH Guided Waves

Highlights

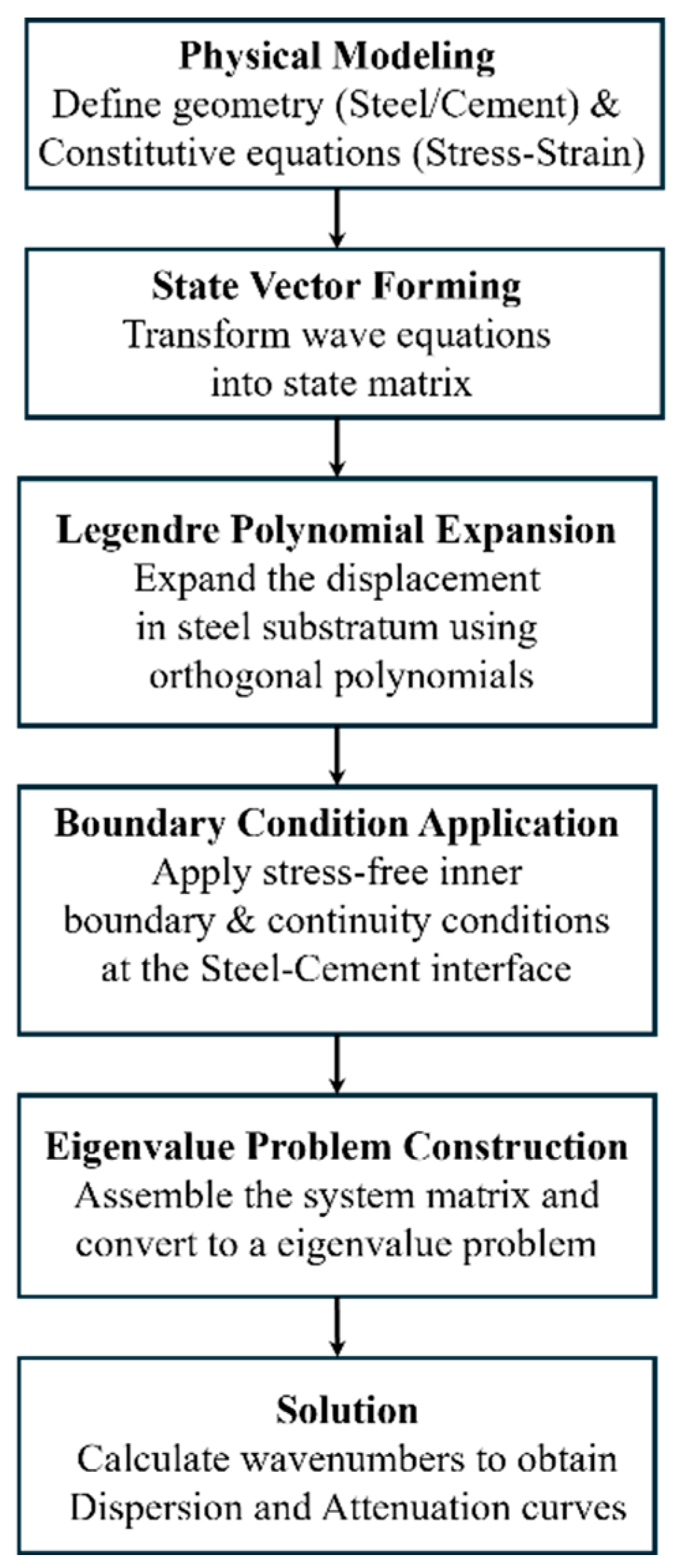

- Based on the state matrix and Legendre polynomial hybrid method, a new numerical method is presented for the investigation of the propagation characteristic of C-SH waves in cementing casing.

- The relationship between the amplitude of SH guided waves and the size of the bonding defects is established through the attenuation coefficient.

- The size of the bonding defects can be experimentally predicted by the attenuation distribution curve.

- It provides a numerical analysis method and experimental prediction basis for the detection of bonding defects in cemented casing.

Abstract

1. Introduction

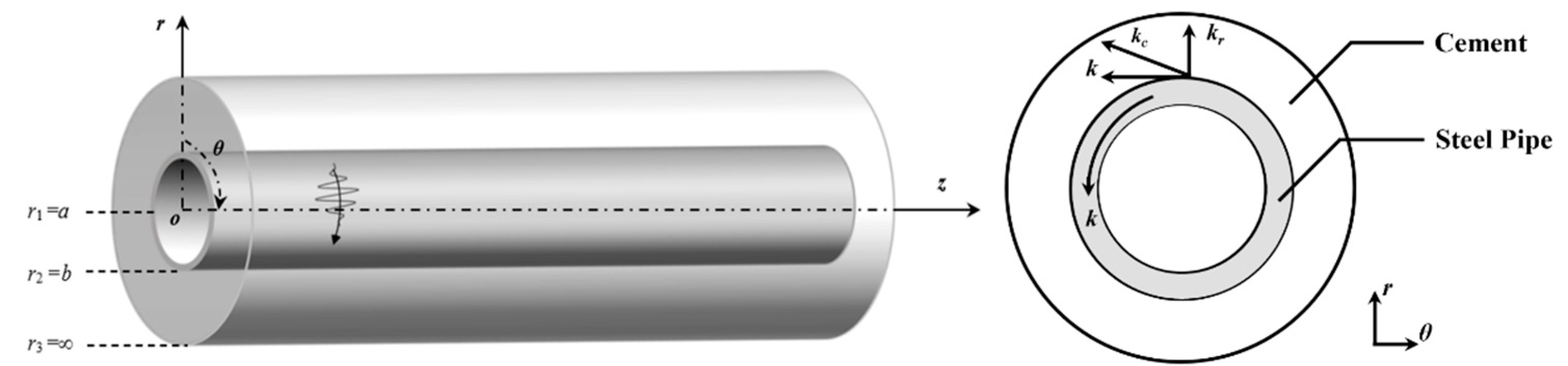

2. Modeling Analysis of C-SH Guided Wave Characteristics

2.1. Theoretical Consideration of C-SH Waves’ Behavior

- Material properties: Both the steel substratum and the cement cladding are isotropic, linear elastic materials.

- Geometry: The structure is infinitely long in the axial (z) direction, and the cement cladding is treated as a semi-infinite domain.

- Deformation: The modeling is based on the small deformation assumption.

- External conditions: Body forces are negligible, and the system is analyzed without external loads other than the guided wave excitation.

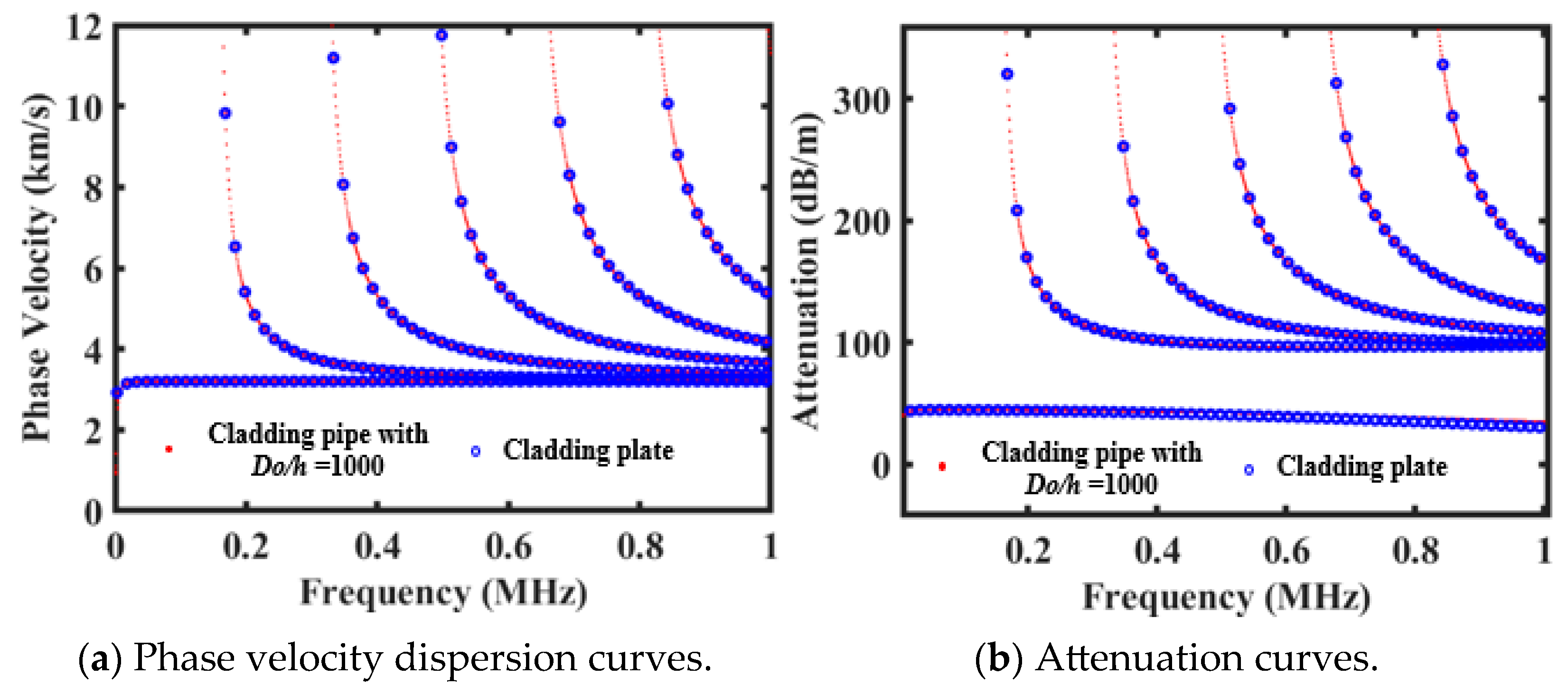

2.2. Numerical Result and Comparison

3. Simulation Analysis of C-SH Wave in Cementing Casing

3.1. Acoustic Time-Domain Modeling

3.2. Bonding Defects and C-SH Guided Wave Attenuation

4. Cementing Casing Experiment Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, X.W.; Khorami, M.; Shi, Y.; Liu, K.Q.; Guo, X.Y.; Austin, S.; Saidani, M. A new approach to improve mechanical properties and durability of low-density oil-well cement composite reinforced by cellulose fibres in microstructural scale. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 191, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y. Numerical investigation of debonding extent development of cementing interfaces during hydraulic fracturing through perforation cluster. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 197, 107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, N.; Olayiwola, O.; Guo, B.; Liu, N. A comprehensive review on the loss of wellbore integrity due to cement failure and available remedial methods. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 207, 109123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bera, A.; Shah, S.N. Potential applications of nanomaterials in oil-and-gas well cementing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 213, 110395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistre, V.; Kinoshita, T.; Schoepf, V. A new generation acoustic logging tool for full waveform sonic and advanced cement evaluation. In Proceedings of the SPWLA 59th Annual Logging Symposium, London, UK, 2–6 June 2018; Society of Petrophysicists and Well Log Analysts: Houston, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Study of Sector Cementation Test (SBT). Master‘s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Uswak, G.; McLafferty, S. Cement imaging through ultrasonics. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 1995, 34, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Li, P.; Ao, K.; Zhang, T.; Xia, Y.; Hou, W. Ultra-Low Density and Low-Friction Cement Slurry Cementing Technologies in Long Sealing Sections of Fuman Oilfield. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2023, 51, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Tao, G. Understanding acoustic methods for cement bond logging. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 139, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benge, G. Cement evaluation: A risky business. SPE Drill. Complet. 2015, 30, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yule, L.; Harris, N.; Hill, M.; Zaghari, B. Temperature Monitoring of Through-Thickness Temperature Gradients in Thermal Barrier Coatings Using Ultrasonic Guided Waves. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2024, 43, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.F.; Li, L.T.; Wu, B. Research on guided circumferential waves in a thin-walled pipe. J. Exp. Mech. 2002, 17, 419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Merwe, J.; De Beer, F. A non-destructive testing method in industrial processes to determine the complex refractive index using ultra-wide band radio. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 7752–7760. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, D.; Bolshakov, A.; Matuszyk, P.J. Utilization of electromagnetic acoustic transducers in downhole cement evaluation. Petrophysics 2015, 56, 479–492. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, R.; Lyu, Y.; Song, G.; Gao, J.; He, C. Finite element simulation of bonding defects in cementing casing based on circumferential SH guided waves. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1195152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, E.C.; Mariani, S.; Cawley, P. The use of circumferential guided waves to monitor axial cracks in pipes. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 22, 2609–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaings, M.; Lowe, M.J.S. Finite element model for waves guided along solid systems of arbitrary section coupled to infinite solid media. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2008, 123, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszyk, P.J. Modeling of guided circumferential SH and Lamb-type waves in open waveguides with semi-analytical finite element and perfectly matched layer method. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 386, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Du, Y.; Tang, J.; Kang, G.; Miao, H. Circumferential SH Wave Piezoelectric Transducer System for Monitoring Corrosion-Like Defect in Large-Diameter Pipes. Sensors 2020, 20, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiades, E.; Lowe, M.J.S.; Craster, R.V. Leaky wave characterisation using spectral methods. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2022, 152, 1487–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Inoue, D. Calculation of leaky Lamb waves with a semi-analytical finite element method. Ultrasonics 2014, 54, 1460–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Tuo, Y.; Tang, X. Attenuation Characteristics of Circumferentially Propagating Quasi-SH Waves in Casing. Chin. J. Geophys. 2023, 66, 4402–4412. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Lyu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Wu, B.; He, C. Modeling guided wave propagation in functionally graded plates by state-vector formalism and the Legendre polynomial method. Ultrasonics 2019, 99, 105953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shui, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X. Snell’s law of elastic waves propagation on moving property interface of time-varying materials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2018, 143, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; He, C.; Lyu, Y.; Wu, B. Guided waves propagation in anisotropic hollow cylinders by Legendre polynomial solution based on state-vector formalism. Compos. Struct. 2019, 207, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | ρ (g/cm3) | C11 (GPa) | C12 (GPa) | C44 (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel | 7.9 | 274.9 | 113.2 | 80.8 |

| Cement | 1.8 | 16.2 | 5.8 | 5.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, J.; Chen, T.; Lyu, Y.; Song, G.; Peng, J.; He, C. Analysis of Bonding Defects in Cementing Casing Using Attenuation Characteristic of Circumferential SH Guided Waves. Sensors 2026, 26, 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010332

Gao J, Chen T, Lyu Y, Song G, Peng J, He C. Analysis of Bonding Defects in Cementing Casing Using Attenuation Characteristic of Circumferential SH Guided Waves. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):332. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010332

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Jie, Tianhao Chen, Yan Lyu, Guorong Song, Jian Peng, and Cunfu He. 2026. "Analysis of Bonding Defects in Cementing Casing Using Attenuation Characteristic of Circumferential SH Guided Waves" Sensors 26, no. 1: 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010332

APA StyleGao, J., Chen, T., Lyu, Y., Song, G., Peng, J., & He, C. (2026). Analysis of Bonding Defects in Cementing Casing Using Attenuation Characteristic of Circumferential SH Guided Waves. Sensors, 26(1), 332. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010332