DP2PNet: Diffusion-Based Point-to-Polygon Conversion for Single-Point Supervised Oriented Object Detection

Abstract

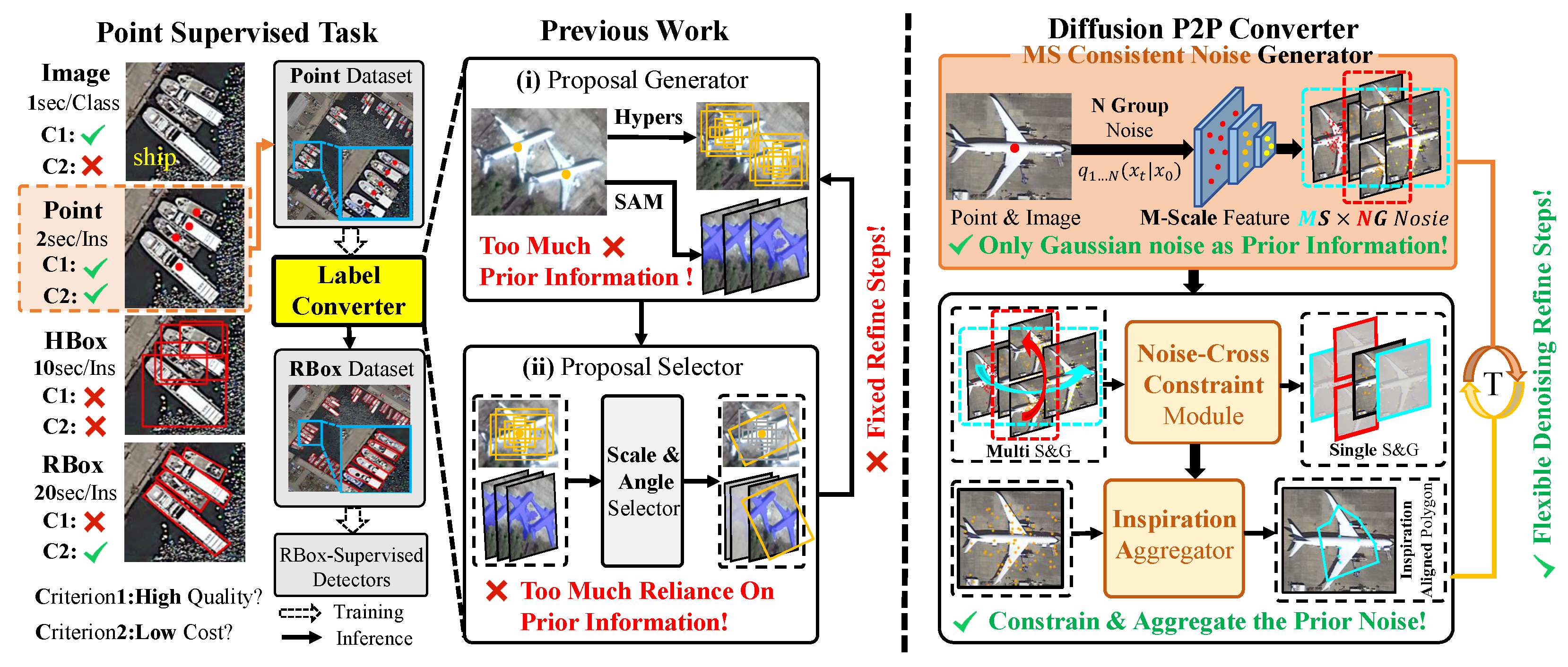

1. Introduction

- (1)

- This paper models oriented object detection under single-point supervision as the generation process of inspirational sampling points on the feature space. To our best knowledge, this is the first study to apply diffusion models to this field.

- (2)

- The DiffusionPoint2Polygon Network presented in this paper not only breaks away from the dependency on complex prior information through the multi-scale consistent noise point generation module during the diffusion process, but also incorporates a Noise Cross-Constraint module during the denoising process to perceive noise sampling points within a range of objects of various sizes and shapes. Subsequently, using the Semantic Key Point Aggregator, it generates pseudo-RBBs based on convex hulls formed by inspiration sampling points that indicate semantically important parts of the object.

- (3)

- Our method exhibits competitive performance on the DOTA and DIOR-R datasets relative to existing approaches that depend on intricate prior information, utilizing solely noise points as the basis for prior knowledge.

2. Related Work

2.1. Fully Supervised Oriented Object Detection

- (1)

- Image Supervision: Image-level supervision only annotates the categories of objects contained in an image, exemplified by the WSODet method.

- (2)

- HBB Supervision: As many existing datasets already have HBB annotations, another weakly supervised learning paradigm, represented by H2RBox and H2RBox-v2, utilizes HBBs as weak annotations to obtain RBBs. Their core is to use the self-supervised signal generated by actively rotating images and the inherent symmetry of objects to accomplish the transition from HBBs to RBBs.

- (3)

- Point Supervision: Point-level annotation provides stronger prior information regarding the object location compared to image-level annotation, while adding relatively minimal annotation costs. Additionally, the cost of point-level annotation is relatively low when compared to other instance-level annotations, such as horizontal or rotated boxes. In the field of oriented object detection, point-level supervision remains a relatively new innovation. Current research primarily focuses on designing a label converter that can transform point annotations into RBBs. PointOBB enhances the MIL network’s ability to perceive the scale and orientation of objects by scaling and rotating the original image, while P2RBOX introduces SAM as a mask generator and designs an inspector module to select high-quality masks for generating RBBs. Label converters can effectively be integrated with the now mature RBox-supervised methods. However, existing label converters heavily rely on the quality of prior information and multi-stage progressive refinement.

2.2. Diffusion Model for Perception Tasks

- (1)

- Application of Diffusion Models in General Object Detection: In recent years, diffusion models have been gradually applied to general object detection tasks. DiffusionDet [19] proposes to model the object detection process as a denoising diffusion process of bounding box coordinates, generating candidate boxes from random noise and gradually optimizing them. DiffusionRPN [20] applies the diffusion model to the region proposal network, generating high-quality candidate regions through noise denoising, which improves the recall rate of small targets. Wang [21] designs a dynamic diffusion optimization module to adjust the denoising steps according to the quality of candidate boxes, realizing adaptive optimization of detection results. These methods all follow the “noise generation—step-by-step denoising” framework, which provides a new idea for solving the problem of object detection.

- (2)

- Research Gaps of Diffusion Models in Oriented Detection: Although diffusion models have shown potential in general object detection, there are still three unsolved problems in oriented detection scenarios: (1) The existing methods do not adapt to the rotation angle prediction requirement of oriented detection. The general object detection only needs to predict the horizontal bounding box, while the oriented detection needs to further predict the rotation angle, and the diffusion model lacks the corresponding angle optimization mechanism. (2) The existing methods are not optimized for the scenario of less annotation information in single-point supervision. Most diffusion-based detection methods rely on full supervision information (such as accurate bounding box annotations) and cannot effectively use the limited information of single-point annotations. (3) The existing methods do not solve the problem of noise adaptation of multi-scale targets. The size difference of targets in oriented detection (especially aerial image detection) is large, and the fixed noise distribution of the existing methods cannot adapt to targets of different scales.

2.3. Positioning of This Study

3. Method

3.1. Preliminaries

- (1)

- Point label converter:

- (2)

- Diffusion Model:

3.2. Architecture and Pipeline

- (1)

- Architecture & Training:

- (2)

- Inference:

3.3. Multi-Scale Consistent Noise Generator

- (1)

- Sampling Point Padding: Due to the diversity of object scales, to ensure an adequate number of sampling points covers the object, we first add some extra points to the point annotations for each object u. Consequently, each object u is associated with a noise point bag containing a fixed number of points N. We explored several padding strategies, such as duplicating existing point annotations or connecting random points. Among these, connecting random points yielded the best results.

- (2)

- Single-scale Consistent Noise Generation: We add Gaussian noise to the set of object-padded points at the u-th location, where the noise scale is controlled by , and employs a monotonically decreasing cosine schedule across different time steps t. Due to the limited receptive field of individual noise sampling points, a point bag containing a fixed number N of points may not effectively cover the object after adding noise generated by a single random seed. Adding more sampling points directly into the point set package would be difficult to optimize due to insufficient supervision information. Therefore, at time step t, this paper uses K different random seeds to generate K groups of different noise point bags for each point set package .

- (3)

- Multi-scale Noise Sampling Point Mapping: Given the diversity of object scales, the size of the parts of objects most valuable for classification also varies. Thus, the noise sampling point bag is mapped onto the multi-scale feature map , enabling each sampling point to obtain deep features with varying receptive fields. The specific process is formalized as follows:where is the noise point bag mapped to the m-th multi-scale feature map; maps noise point coordinates to for deep feature extraction; is the original noise point bag set; is the m-th FPN output feature map ( for P2/P3/P4); M is the number of multi-scale feature layers.

3.4. Noise Cross-Constraint Module

3.5. Semantic Key Point Aggregator

3.6. Theoretical Analysis

3.6.1. Mapping Relationship Between Diffusion Process and Pseudo-Box Generation

3.6.2. Convergence Analysis of Noise Cross-Constraint Module

4. Experiment

4.1. Datasets and Implementation Details

- (1)

- Datasets: DOTA-v1.0 [29] is presently among the most widely employed datasets for oriented object detection in aerial images. It comprises 2806 images, 188,282 instances annotated with RBoxes, and is classified into 15 categories. For training and testing, we follow a standard protocol by cropping images into 1024 × 1024 patches with a stride of 824. DIOR-R [30] is an aerial image dataset annotated by RBoxes based on its horizontal annotation version DIOR. The dataset consists of 23,463 images, 190,288 instances, and is classified into 20 categories.

- (2)

- Single-Point Annotation: In order to accurately simulate manually annotated point annotations, this paper does not directly use the center point of the RBB label as the point annotation. Instead, it selects random points within a range of 10% relative to the width and height of the RBB near the center point as the single-point annotations, thereby reproducing the deviations in manual annotations. The impact of the deviation range will be discussed in Section 5.

- (3)

- Training Details: The algorithms employed in the experiments of this paper are from the open-source library MMRotate [31] based on Pytorch. This paper follows the default settings in MMRotate. The experiments in this paper were conducted on the NVIDIA 4090 with 24GB of memory. For training the DP2PNet with single-point annotations and the fully supervised rotation box algorithm trained with pseudo-RBBs generated by the DP2PNet in this paper, a “1×” schedule including 12 epochs was used. For the compared algorithms, we followed their base settings.

- (4)

- Evaluation Metric: Mean Average Precision (mAP) is used as the main metric to compare our method in this paper with existing methods. To evaluate the quality of pseudo-RBBs generated by DP2PNet from point annotations, this paper reports the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) between manually annotated RBBs (GT) and pseudo-RBBs.

4.2. Performance Comparisons

4.2.1. Comparisons Results

- (1)

- Results on DOTA-v1.0: As shown in Table 3, DP2PNet achieves 53.82% on the by training Rotated FCOS, surpassing point converters such as Point2RBox and PointOBB, which use manually designed hyperparameters. Additionally, our method exhibits competitive performance on the 7- compared to the P2RBox method that uses the SAM method as prior information.

- (2)

- Results on DIOR-R: As shown in Table 4, DP2PNet achieved 52.14% and 53.61% on mAP50 by training Rotated FCOS and Oriented R-CNN [32], respectively. DP2PNet’s performance surpasses the two-stage alternative, Point-to-HBox-to-RBox (P2BNet + H2RBox-v2), on the metric. Moreover, DP2PNet achieves a 21% improvement in performance on the 8- metric compared to the point converter PointOBB, and it also demonstrates competitive performance with SAM and fully supervised methods.

4.2.2. Analysis of Performance Difference

4.2.3. Comparison of Method Complexity

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Ablation Study

5.1. The Effect of Multi-Scale Map

5.2. The Effect of Single-Scale Consistent

5.3. The Effect of Progressive Refinement

5.4. The Effect of Point Padding Strategy

5.5. The Effect of Point Annotation Deviation Range

5.6. The Effect of Noise Level

5.7. The Effect of Target Type

5.8. Cross-Dataset Generalization Experiment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sikic, F.; Kalafatic, Z.; Subasic, M.; Loncaric, S. Enhanced Out-of-Stock Detection in Retail Shelf Images Based on Deep Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zeng, X.; Xie, K.; Wen, C.; He, J.; Zhang, W. Efficient Defect Detection of Rotating Goods under the Background of Intelligent Retail. Sensors 2024, 24, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Shi, B.; Bai, X. Textboxes++: A single-shot oriented scene text detector. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 3676–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhukov, A.; Rivero, A.; Benois-Pineau, J.; Zemmari, A.; Mosbah, M. A Hybrid System for Defect Detection on Rail Lines through the Fusion of Object and Context Information. Sensors 2024, 24, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Shi, J.; Wei, S.; Ahmad, I.; Zhan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, D.; Li, J.; et al. Balance learning for ship detection from synthetic aperture radar remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 182, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, D.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Meng, X.; Zhang, G. An Aerial Image Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv5. Sensors 2024, 24, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, T.; Huang, S.; Li, K. A hybrid optimization framework for UAV reconnaissance mission planning. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 173, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, G.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, J. H2rbox: Horizontal box annotation is all you need for oriented object detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.06742. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yan, J.; Da, F. H2rbox-v2: Boosting hbox-supervised oriented object detection via symmetric learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.04403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Sun, J. Points as queries: Weakly semi-supervised object detection by points. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 8823–8832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yu, X.; Han, X.; Hassan, N.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Shi, H.; Han, Z.; Ye, Q. Point-to-box network for accurate object detection via single point supervision. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, G.; Yu, X.; Yu, W.; Han, X.; Yang, X.; Li, G.; Jiao, J.; Han, Z. P2RBox: A Single Point is All You Need for Oriented Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.13128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Yang, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yan, J.; Li, Y. PointOBB: Learning Oriented Object Detection via Single Point Supervision. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16730–16740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Da, F.; Yan, J.; Dai, J.; Qiao, Y. Point2RBox: Combine Knowledge from Synthetic Visual Patterns for End-to-end Oriented Object Detection with Single Point Supervision. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.14758. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Meng, C.; Ermon, S. Denoising diffusion implicit models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.02502. [Google Scholar]

- Dhariwal, P.; Nichol, A. Diffusion models beat gans on image synthesis. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 8780–8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sun, P.; Song, Y.; Luo, P. Diffusiondet: Diffusion model for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 19830–19843. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, H.; Ren, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, G.; Fang, Y.; Gu, G.; Xu, H.; Lu, C. Reactive Diffusion Policy: Slow-Fast Visual-Tactile Policy Learning for Contact-Rich Manipulation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.02881. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Dou, Z.; Bao, C.; Shi, Z. Diffusion Mechanism in Residual Neural Network: Theory and Applications. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, H.; Vedaldi, A. Weakly Supervised Deep Detection Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2016, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2846–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Hu, H.; Wang, L.; Lin, S. Reppoints: Point set representation for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9657–9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, P.Y.; Lin, C.H.; Kao, W.C. A novel plug-in module for fine-grained visual classification. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.03822. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.; Wang, S.; Zhu, E.; Liu, X.; Chen, W. Group-Attention Transformer for Fine-Grained Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Security; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, H.; Fu, K.; Yang, J.; Sun, X.; Yan, M.; Guo, Z. Automatic ship detection in remote sensing images from google earth of complex scenes based on multiscale rotation dense feature pyramid networks. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, R.A. On the identification of the convex hull of a finite set of points in the plane. Inf. Process. Lett. 1973, 2, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA: A large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 3974–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wan, G.; Cheng, G.; Meng, L.; Han, J. Object detection in optical remote sensing images: A survey and a new benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 159, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Hou, L.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; Yan, J.; Lyu, C.; et al. Mmrotate: A rotated object detection benchmark using pytorch. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisbon, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 7331–7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Cheng, G.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Han, J. Oriented R-CNN for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3520–3529. [Google Scholar]

- Peyrard, C.; Baccouche, M.; Mamalet, F.; Garcia, C. ICDAR2015 competition on Text Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, ICDAR 2015, Nancy, France, 23–26 August 2015; pp. 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Prior Type | Optimization Stage Flexibility | Model Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| PointOBB | Manual design | Fixed (5 stages) | MIL + fixed-stage refinement |

| P2RBox | External model (SAM mask) | Fixed (3 stages) | SAM + inspector module |

| Ours (DP2PNet) | Noise prior (Gaussian noise) | Dynamic (1–7 stages) | Diffusion model + MIL + graph convolution |

| Method | Prior Type | Optimization Flexibility | Core Module | Angle Prediction Method | mAP50 (DOTA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PointOBB | manual design (Sc & Ra & An) | fixed (5 stages) | MIL + fixed-stage refinement | direct prediction | 30.08% |

| P2RBox | external model (SAM mask) | fixed (3 stages) | SAM + inspector module | mask-based fitting | 58.40% |

| DiffusionDet | gaussian noise | dynamic | denoising diffusion for bounding boxes | coordinate optimization | - |

| Ours (DP2PNet) | gaussian noise | dynamic (1–7 stages) | Diffusion + MIL + graph convolution | convex hull of semantic points | 53.82% |

| Method | R-Form | P-Form | PL | BD | GTF | SV | LV | SH | HA | 7-mAP50 | mAP50 | Annotation Cost Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBox-supervised: | ||||||||||||

| Rotated RetinaNet: | RBox | - | 88.7 | 77.6 | 58.2 | 74.6 | 71.6 | 79.1 | 62.6 | 73.19 | 68.69 | 100% |

| Rotated FCOS: | RBox | - | 88.4 | 76.8 | 59.2 | 79.2 | 79.0 | 86.9 | 69.3 | 76.96 | 71.28 | 100% |

| HBox-supervised: | ||||||||||||

| H2RBox: | RBox | An | 88.5 | 73.5 | 56.9 | 77.5 | 65.4 | 77.9 | 52.4 | 70.29 | 67.21 | 63.5% |

| H2RBox-v2: | RBox | An | 89.0 | 74.4 | 60.5 | 79.8 | 75.3 | 86.9 | 65.2 | 75.88 | 72.52 | 63.5% |

| Point-supervised: | ||||||||||||

| P2BNet + H2RBox-v2 | HBox | Sc & Ra | 11.0 | 44.8 | 15.4 | 36.8 | 16.7 | 27.8 | 12.6 | 23.58 | 21.87 | 36.5% |

| SAM (FCOS): | Mask | - | 78.2 | 61.7 | 45.1 | 68.7 | 64.8 | 78.6 | 45.7 | 63.26 | 50.84 | 85% |

| P2RBOX (FCOS): | Mask | SAM | 86.7 | 66.0 | 47.4 | 72.4 | 71.3 | 78.6 | 48.4 | 67.25 | 58.40 | - |

| Point2RBox: | RBox | Sc & Ra & An | 66.4 | 59.5 | 52.6 | 54.1 | 53.9 | 57.3 | 22.9 | 52.38 | 44.90 | 36.5% |

| PointOBB (FCOS): | RBox | Sc & Ra & An | 26.1 | 65.7 | 59.4 | 65.8 | 34.9 | 29.8 | 21.8 | 43.35 | 30.08 | 36.5% |

| Ours (FCOS): | Polygon | Noise | 81.3 | 63.2 | 48.4 | 70.6 | 67.1 | 77.2 | 46.1 | 64.84 | 52.37 | 36.5% |

| Ours (Oriented R-CNN): | Polygon | Noise | 82.6 | 64.1 | 49.8 | 71.2 | 68.9 | 78.1 | 48.4 | 66.16 | 53.82 | 36.5% |

| Method | R-Form | P-Form | APL | BF | BC | GTF | HA | SH | TC | VE | 8-mAP50 | mAP50 | Annotation Cost Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBox-supervised: | |||||||||||||

| Rotated RetinaNet: | RBox | - | 58.9 | 73.1 | 81.3 | 32.5 | 32.4 | 75.1 | 81.0 | 44.5 | 64.26 | 54.96 | 100% |

| Rotated Faster-R-CNN: | RBox | - | 63.1 | 79.1 | 82.8 | 40.7 | 55.9 | 81.1 | 81.4 | 65.6 | 69.88 | 62.80 | 100% |

| Rotated FCOS: | RBox | - | 61.4 | 74.3 | 81.1 | 32.8 | 48.5 | 80.0 | 63.9 | 42.7 | 66.59 | 59.83 | 100% |

| Image-supervised: | |||||||||||||

| WSODet: | HBox | Sc & Ra | 20.7 | 63.2 | 67.3 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 40.0 | 6.1 | 28.46 | 22.20 | 5% |

| HBox-supervised: | |||||||||||||

| H2RBox: | RBox | An | 68.1 | 75.0 | 85.4 | 34.7 | 44.2 | 79.3 | 81.5 | 40.0 | 67.80 | 57.80 | 63.5% |

| H2RBox-v2: | RBox | An | 67.2 | 55.6 | 80.8 | 80.3 | 25.3 | 78.8 | 82.5 | 42.0 | 64.06 | 57.64 | 63.5% |

| Point-supervised: | |||||||||||||

| P2BNet+H2RBox-v2 | HBox | Sc & Ra | 51.6 | 65.2 | 78.3 | 44.9 | 2.3 | 35.9 | 79.0 | 10.3 | 45.94 | 23.61 | 36.5% |

| SAM (FCOS): | Mask | - | 62.1 | 73.2 | 80.4 | 76.6 | 12.2 | 73.5 | 51.7 | 36.5 | 66.58 | 53.73 | 85% |

| PointOBB (FCOS): | RBox | Sc & Ra & An | 58.4 | 70.7 | 77.7 | 74.2 | 9.9 | 69.0 | 46.1 | 32.4 | 54.80 | 37.31 | 36.5% |

| Ours (Rotated FCOS): | Polygon | Noise | 59.8 | 72.3 | 79.3 | 76.9 | 14.1 | 74.2 | 49.3 | 34.8 | 65.81 | 52.14 | 36.5% |

| Ours (Oriented R-CNN): | Polygon | Noise | 60.1 | 73.4 | 80.2 | 77.9 | 13.4 | 74.1 | 50.3 | 35.6 | 66.43 | 53.61 | 36.5% |

| Method | Number of Parameters (M) | Inference Speed (FPS) | Prior Dependence | Training Data Requirement (10% Annotation Data Performance Retention Rate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2RBOX [12] (FCOS) | 45.6 | 15 | High (SAM mask) | 72% |

| PointOBB [13] (FCOS) | 39.8 | 18 | High (Sc & Ra & An) | 68% |

| Ours (Oriented R-CNN) | 38.2 | 22 | Low (Noise prior) | 85% |

| FPN-P2 | FPN-P3 | FPN-P4 | mIOU | 7-mAP 50 | mAP 50 | mAP50 (Large-Scale Targets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | - | - | 51.87 | 59.81 | 44.67 | 42.3 |

| - | ✓ | - | 55.21 | 62.15 | 48.72 | 49.8 |

| - | - | ✓ | 49.14 | 58.78 | 43.15 | 45.9 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 58.98 | 64.84 | 52.37 | 53.8 |

| K | mIOU | 7-mAP 50 | mAP 50 | Computational Burden (GFLOPs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50.32 | 55.89 | 48.92 | 15.6 |

| 2 | 54.74 | 61.45 | 55.67 | 22.3 |

| 3 | 58.98 | 64.84 | 58.98 | 28.9 |

| 4 | 58.24 | 64.13 | 58.24 | 35.6 |

| S | mIOU | mAP 50 | Pseudo-RBB Deviation (Pixel) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51.57 | 37.56 | 15.3 |

| 3 | 54.21 | 40.65 | 8.7 |

| 5 | 58.98 | 43.15 | 3.2 |

| 7 | 57.76 | 42.87 | 4.1 |

| Pad | mIOU | mAP 50 | Point Bag Coverage Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeat | 58.21 | 42.74 | 65.3 |

| Gaussian | 57.71 | 42.43 | 78.6 |

| Uniform | 58.98 | 43.12 | 92.1 |

| PR | mIOU | mAP 50 | Pseudo-RBB Accuracy Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 58.98 | 43.15 | 89.2 |

| 30% | 58.84 | 43.09 | 88.7 |

| 50% | 58.86 | 43.11 | 88.9 |

| Noise Std () | Method | mIOU | mAP 50 | Performance Attenuation Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | Ours | 59.23 | 43.28 | 0 |

| 0.1 | PointOBB | 52.15 | 38.21 | 0 |

| 0.1 | P2RBox | 62.31 | 58.67 | 0 |

| 0.3 | Ours | 59.01 | 43.21 | 0.16 |

| 0.3 | PointOBB | 50.32 | 36.54 | 4.37 |

| 0.3 | P2RBox | 60.12 | 56.32 | 4.01 |

| 0.5 | Ours | 58.98 | 43.15 | 0.30 |

| 0.5 | PointOBB | 48.21 | 34.87 | 8.74 |

| 0.5 | P2RBox | 58.45 | 54.15 | 7.70 |

| 0.7 | Ours | 58.76 | 43.02 | 0.60 |

| 0.7 | PointOBB | 45.12 | 32.15 | 15.86 |

| 0.7 | P2RBox | 56.23 | 51.87 | 11.59 |

| 0.9 | Ours | 58.54 | 42.89 | 0.90 |

| 0.9 | PointOBB | 42.31 | 29.87 | 21.83 |

| 0.9 | P2RBox | 54.12 | 49.65 | 15.37 |

| Target Type | Method | mIOU | mAP 50 | Pseudo-RBB Edge Accuracy (Pixel) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Vehicle (Small-scale) | Ours | 58.7 | 50.3 | 3.5 |

| Small Vehicle (Small-scale) | PointOBB | 52.3 | 45.6 | 5.2 |

| Small Vehicle (Small-scale) | P2RBox | 62.3 | 58.6 | 2.1 |

| Harbor (Large-scale) | Ours | 64.1 | 53.8 | 4.2 |

| Harbor (Large-scale) | PointOBB | 52.3 | 45.9 | 6.8 |

| Harbor (Large-scale) | P2RBox | 60.2 | 56.3 | 3.8 |

| Baseball Diamond (Irregular shape) | Ours | 61.5 | 52.7 | 3.9 |

| Baseball Diamond (Irregular shape) | PointOBB | 48.7 | 42.3 | 7.1 |

| Baseball Diamond (Irregular shape) | P2RBox | 57.8 | 54.1 | 3.5 |

| Method | mAP 50 | 8-mAP 50 | Performance Retention Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 48.2 | 60.1 | 90.0 |

| PointOBB | 39.5 | 48.7 | 80.3 |

| P2RBox | 42.1 | 52.3 | 78.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, P.; Zhang, L.; Qu, T. DP2PNet: Diffusion-Based Point-to-Polygon Conversion for Single-Point Supervised Oriented Object Detection. Sensors 2026, 26, 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010329

Li P, Zhang L, Qu T. DP2PNet: Diffusion-Based Point-to-Polygon Conversion for Single-Point Supervised Oriented Object Detection. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):329. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010329

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Peng, Limin Zhang, and Tao Qu. 2026. "DP2PNet: Diffusion-Based Point-to-Polygon Conversion for Single-Point Supervised Oriented Object Detection" Sensors 26, no. 1: 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010329

APA StyleLi, P., Zhang, L., & Qu, T. (2026). DP2PNet: Diffusion-Based Point-to-Polygon Conversion for Single-Point Supervised Oriented Object Detection. Sensors, 26(1), 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010329