An Autonomous Land Vehicle Navigation System Based on a Wheel-Mounted IMU

Abstract

1. Introduction

- An autonomous navigation system is proposed and implemented based on a single wheel-mounted MEMS IMU, in which the displacements between the IMU’s sensitive axes center and the IMU’s rotation center, as well as the gyro scale factor and non-orthogonal errors, is estimated online; its navigation performance is investigated through kinematic field tests, which indicate that the proposed wheeled INS is able to provide reliable PVA solutions in GNSS-denied environment.

- The observability of wheeled INS is studied thoroughly and analytically, which identifies that the azimuth error is unobservable under vehicle normal dynamics and becomes the main cause of velocity and position errors in the east and north directions. Thanks to the improved observability of the gyro errors perpendicular to the rotation axis, the azimuth errors can be effectively suppressed. This leads to the higher navigation accuracy of wheeled INS over the OD/NHC/INS, in which both of the azimuth error and the associated gyro bias are unobservable.

- To ensure a high level of estimation accuracy and limit the number of particles, we proposed a hybrid EKF and PF (referred to as EPF) to continuously estimate the land vehicle navigation states. The impact of the initial particle numbers on EPF estimation accuracy is also studied, and the performance of EPF is evaluated through kinematic field tests.

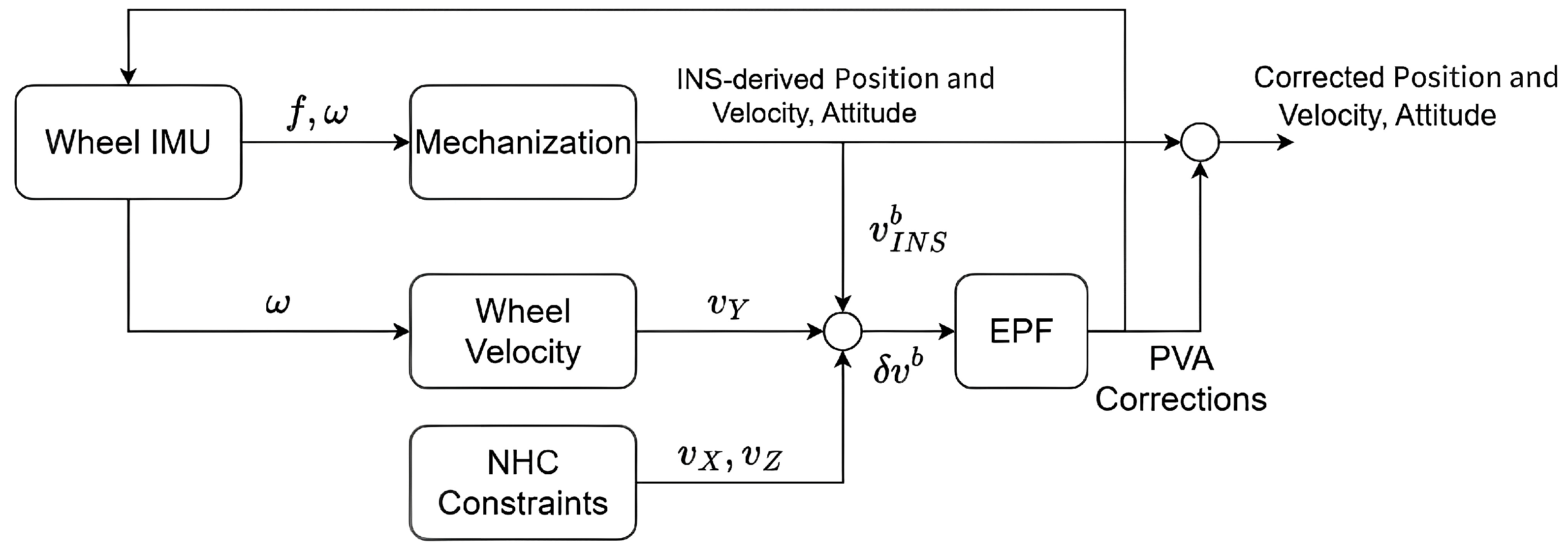

2. Wheeled INS Algorithm

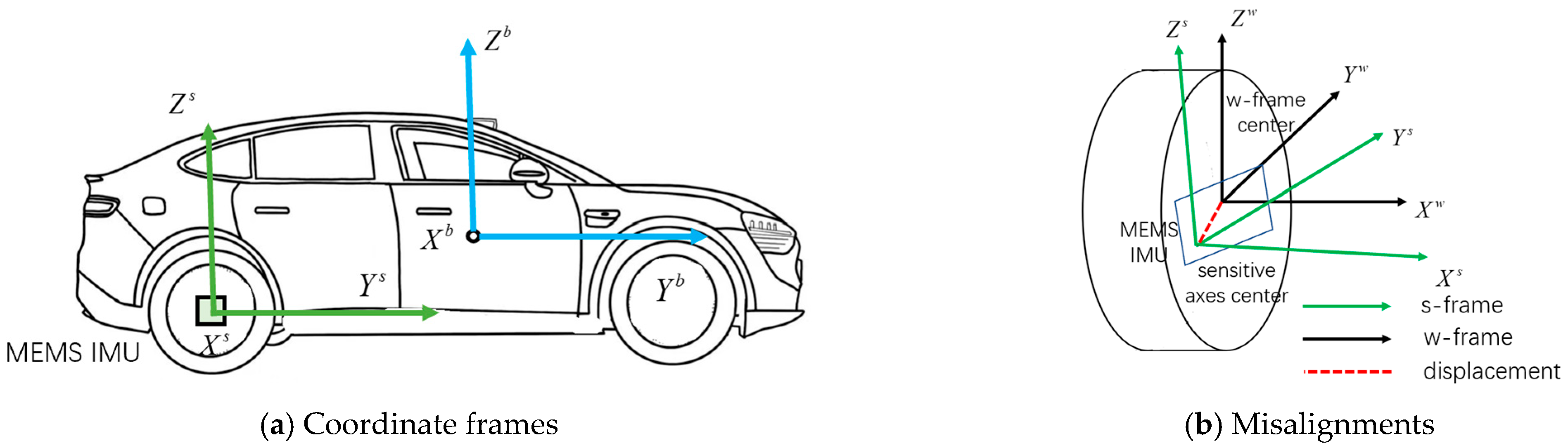

2.1. Coordinate Frames and Misalignments

2.2. System and Measurement Models

3. Observability Analysis of Wheeled INS

3.1. Observability of Wheeled INS Under Uniform Linear Motion

3.2. Effects of Forward Acceleration and Turning Motions on System Observability

3.2.1. Effects of Forward Accelerations

3.2.2. Effects of Turning Motions

4. Proposed EPF of Wheeled INS

- Initialize the system states and their covariance matrix, randomly generate independent and identically distributed N samples from the prior probability distribution .

- Assign an equal weight of 1/N to all particles .

- When receiving the IMU measurements, calculate the PVA states for each particle through the INS mechanization algorithm.

- For each particle, calculate the transition matrix based on the error model in Equations (5) and (6) and predict the covariance matrix of the system states using the following equation:

- When the observation is available, implement the EKF update for each particle based on Equations (34)–(36).

- 2.

- Sample a new state from the Gaussian proposal distribution based on Equation (37).

- 3.

- For , evaluate the importance weights of each particle according to Equation (38).

- 4.

- Normalize the weight for each particle, as stated in Equation (39).

- Compute the effective sample size and threshold based on Equation (40)

- 2.

- If , the particles remain as such, i.e., for each particle with weight ; otherwise, implement the resampling.

- 3.

- Construct the cumulative distribution function according to Equation (41), and generate a systematic sampling point according to Equation (42). For each , find the index , satisfying . Eventually, copy the particles and reset the weights according to Equations (43) and (44).

- The state estimation and its corresponding covariance matrix are calculated using all particles, based on Equation (45),

5. Kinematic Field Test Results and Analysis

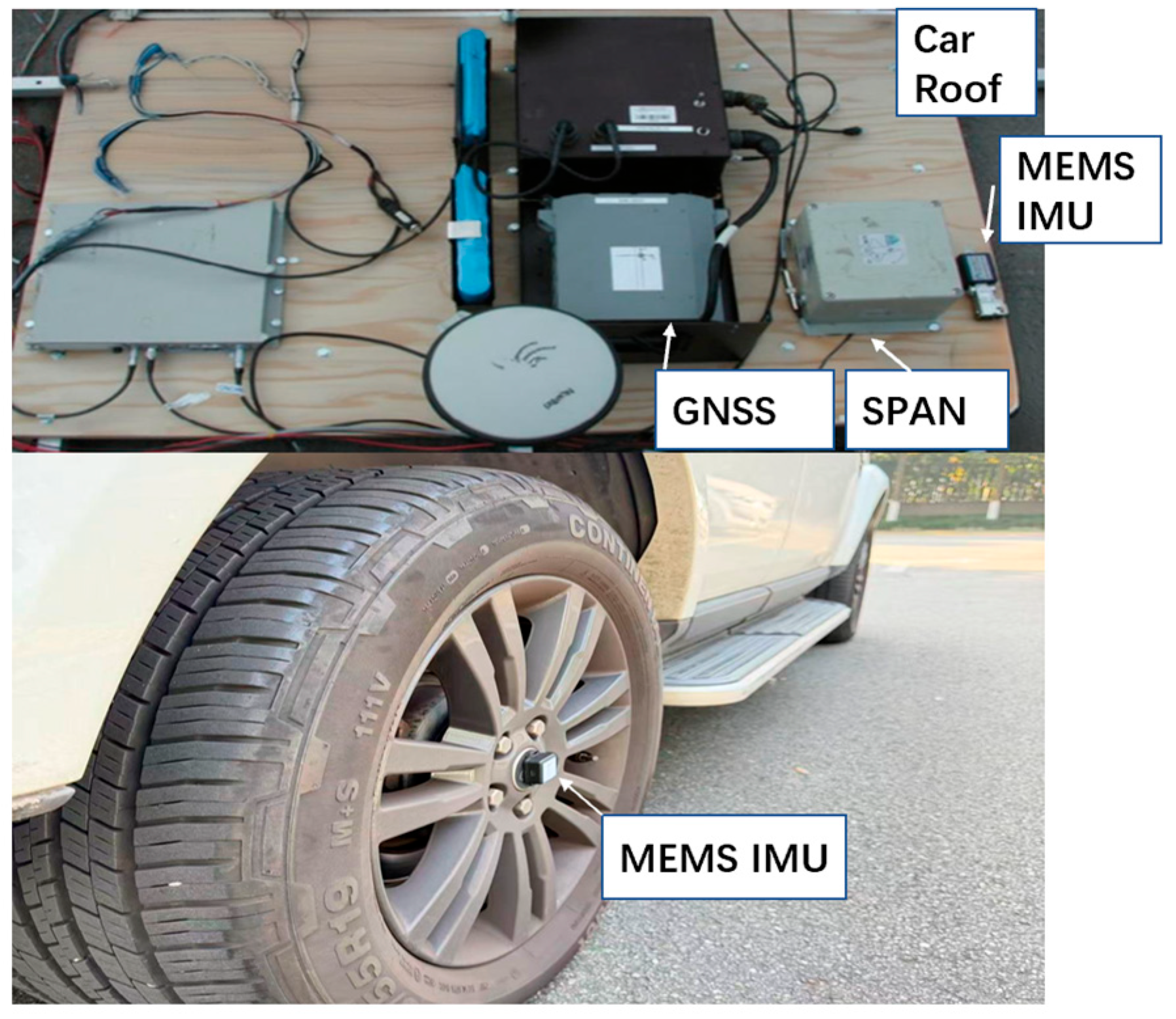

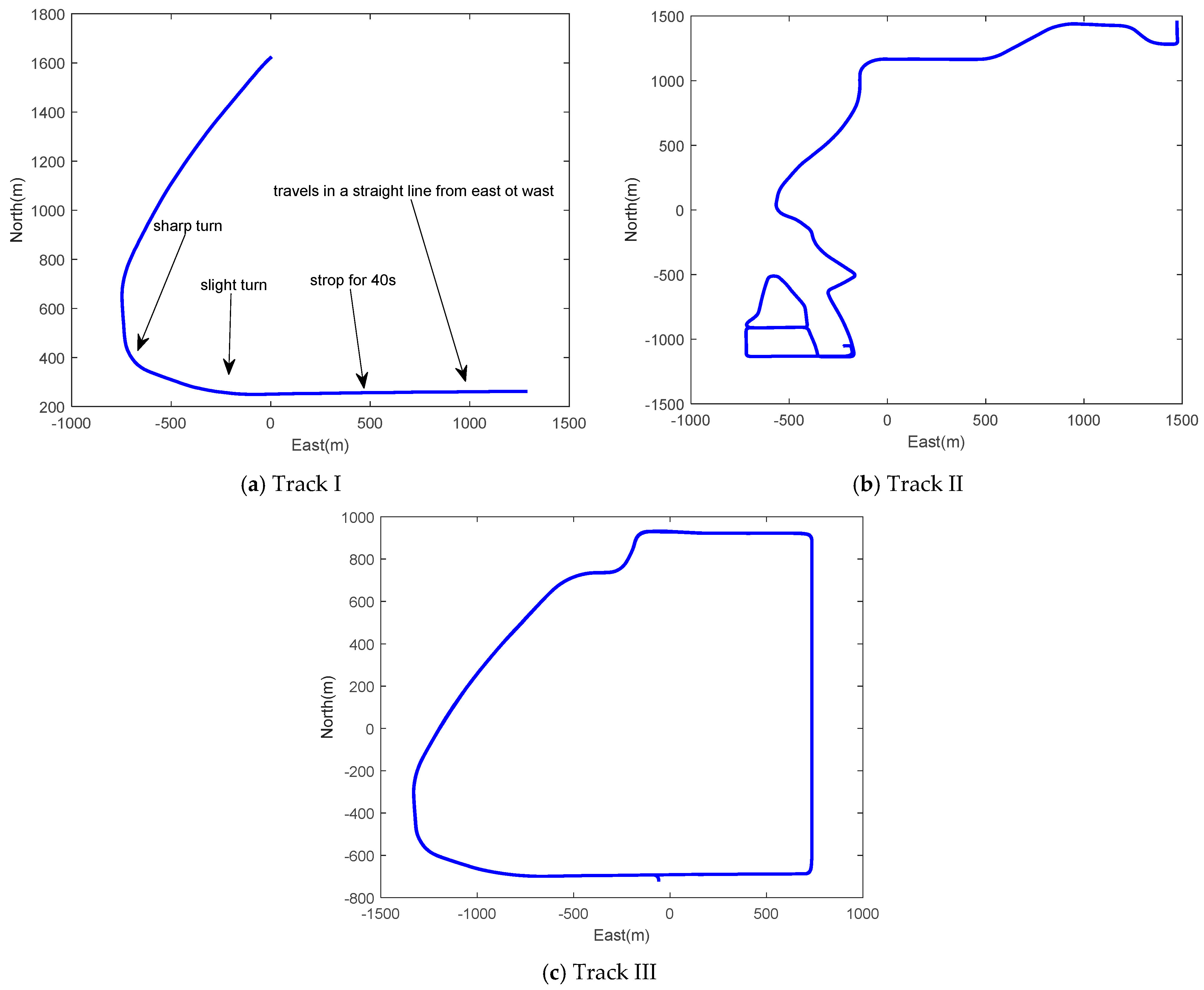

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Observability Verification of Wheeled INS

- Under uniform linear motion, the observability of the 17-dimensional state vector can be divided into five levels based on the eigenvalues. The highest observability is for the velocity errors for the upward and eastward directions, which can be directly observed from the measurements (since the vehicle moves from east to west, the heading error has no effect on the eastward velocity). The second level is the attitude error for the northward direction, which can be derived from the time rate of the velocity measurements. The third level includes the Y-axis and Z-axis accelerometer errors and gyroscope errors. Due to the absence of acceleration, the displacement, gyroscope scale factor errors, and non-orthogonal errors are coupled with the accelerometer and gyroscope biases, forming jointly observable states. The fourth level is the coupled joint state of the attitude error of the eastward direction and the X-axis accelerometer error. The last level includes the velocity error for the northward direction and the azimuth error. This is because the azimuth error is hardly observable, and its error projects onto the northward velocity error.

- Acceleration primarily enhances the observability of the Y-axis and Z-axis accelerometer biases, gyroscope biases, as well as the displacement, scale factor errors, and non-orthogonal errors. Based on eigenvalues, the observability of all error states can be divided into four levels. The highest observability remains with the velocity errors of the upward and eastward directions. The second level includes the attitude error for the northward direction, Y-axis and Z-axis accelerometer biases, and gyroscope biases, as well as the displacement, scale factor errors, and non-orthogonal errors. The third level is the coupled joint state of the attitude error for the eastward direction and the X-axis accelerometer error. The last level remains the velocity error of northward direction and the azimuth error.

- Circular motion enhances the observability of the attitude error for the east direction and the X-axis accelerometer bias but simultaneously reduces the observability of the velocity error for the eastward direction. This is because circular motion projects the azimuth error onto the eastward velocity. Based on eigenvalues, the observability of all states can be divided into three levels. The first level includes the directly observable vertical velocity error. The second level includes the horizontal attitude errors, accelerometer and gyroscope biases, displacement, gyroscope scale factor errors, and non-orthogonal errors. The third level includes the hardly observable azimuth error, as well as the horizontal velocity errors affected by it.

- The variance in the velocity error in the upward direction, the accelerometer biases of Y- and Z-axes, and the gyro biases of the X-, Y- and Z-axes, as well as the displacements between the IMU center to the wheel rotation center and the scale factor and non-orthogonal error states, are quickly reduced, which indicates that these error states are observable.

- During the initial 150 s, as the vehicle is traveling along the east–west direction, the pitch error and roll error become and , respectively, according to Equation (32); therefore, the variance in roll errors is quickly reduced. As and the accelerometer bias of the X-axis are coupled error states and only their linear combination is observable, the variance in both error states almost remains unchanged until the vehicle’s sharp turn makes them become observable after 170 s.

- As the azimuth error is unobservable, its variance almost remains unchanged, which causes the unreduced variance in the velocity errors for the eastward and northward directions. There are two periods during which the projections of azimuth error variance in velocity errors are eliminated. The first period is the initial 150 s, during which the vehicle travels from east to west and the velocity error of the eastward direction becomes . The second period is the vehicle’s static period from about 60–100 s, during which the velocity error in the north direction becomes , according to Equation (31).

- The gyro bias of the Z-axis is unobservable and its variance remains almost unchanged, which leads to the variance in another unobservable bias, azimuth error, diverging over time. This leads to a much greater variance in the velocity error for the eastward and northward directions compared to the wheeled INS.

- The accelerometer bias of Y-axis and the roll errors are coupled states, and they cannot be separately observed during the linear motion, which also affects the observability of velocity errors in the upward direction according to Equation (31), although they become observable with sharp turning motions.

5.3. Navigation Performance of Wheeled INS

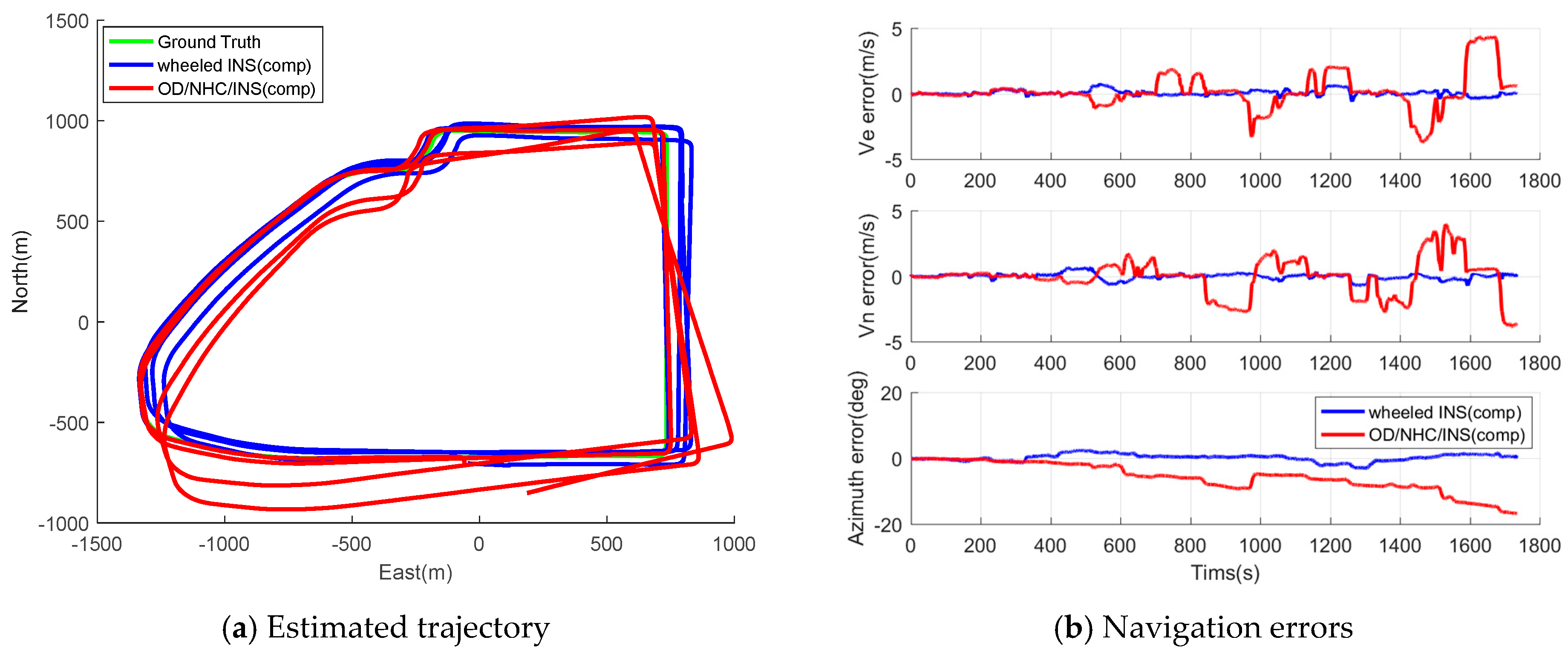

5.3.1. Comparison Between Wheeled INS and OD/NHC/INS

- The proposed wheeled INS is able to offer reliable navigation solutions in GNSS-denied environments. The heading error and maximum position drift rate is 1.28° and 0.85% for Track II, while the same metric for Track III is 1.42 and 0.54%. The maximum position drift for Track III is even lower than that of the Track II. This is because the position errors can be suppressed to some extent due to loops in the trajectory, as the position error usually drifts along one direction in INSs.

- The wheeled INS outperforms the OD/NHC/INS in terms of positioning accuracy overall; the RMS of horizontal position, velocity errors, and azimuth errors—as well as the maximum position drift rate of wheeled INS—are improved by 30.94%, 36.00%, 44.83%, and 12.37%, respectively, compared to the OD/NHC/INS for Track II. The same figures for wheeled INS are improved by 56.06%, 76.29%, 81.56%, and 46.53%, respectively, for Track III. As Track III is a much longer trajectory than Track II, this indirectly reflects the fact that the navigation errors can be well mitigated in wheeled INS, and the longer the distance traveled, the greater improvements over OD/NHC/INS can be observed.

- During the initial period, the wheeled INS solutions are close to those of the OD/NHC/INS. This is because the gyro bias of the Z-axis remains stable and close to its initial estimates, which only introduces small azimuth and velocity errors in both systems.

- After the initial periods, the gyro bias of the Z-axis drifts away from its initial estimates, and the compensation for these errors depends on its observability in both systems. In wheeled INS, the gyro bias can be well estimated due to its high observability, which effectively limits the azimuth and horizontal velocity errors; in contrast, such error is unobservable and hardly to be estimated in OD/NHC/INS, which introduces accumulated azimuth and horizontal velocity errors.

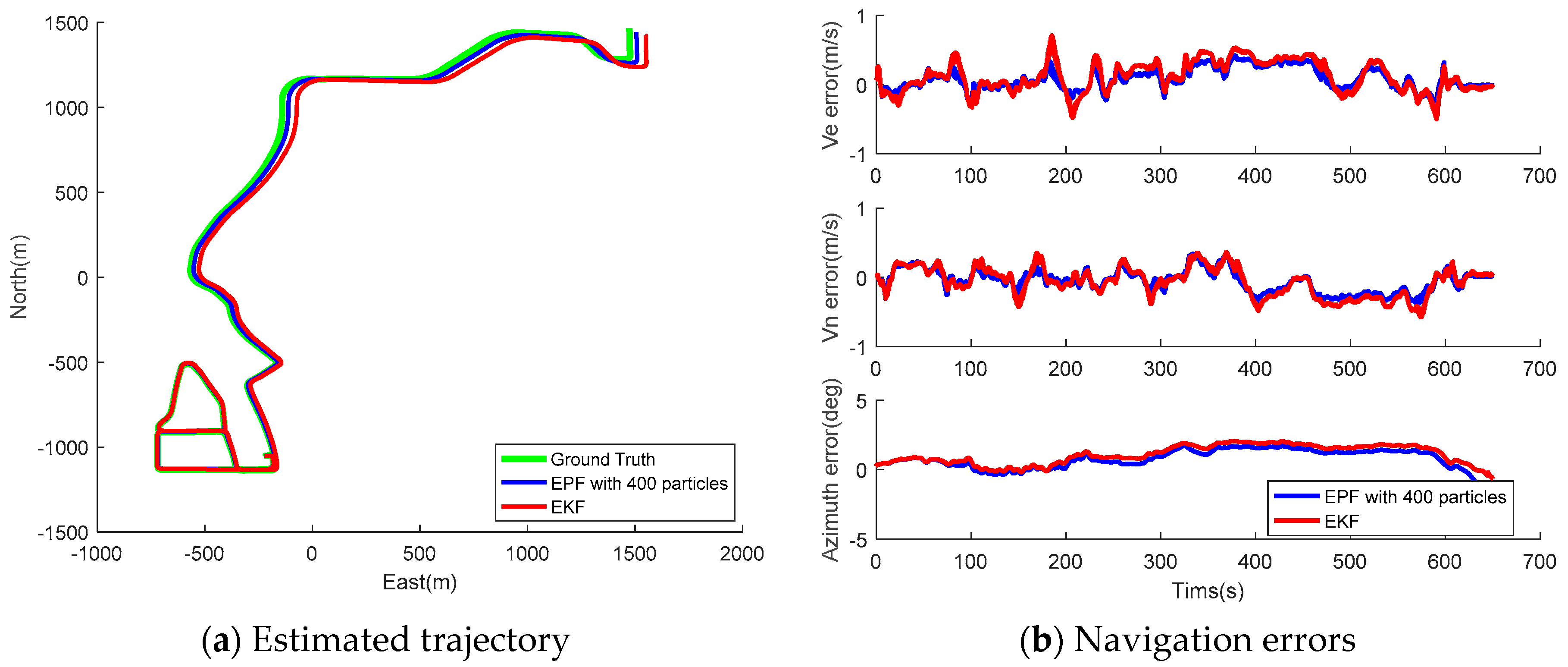

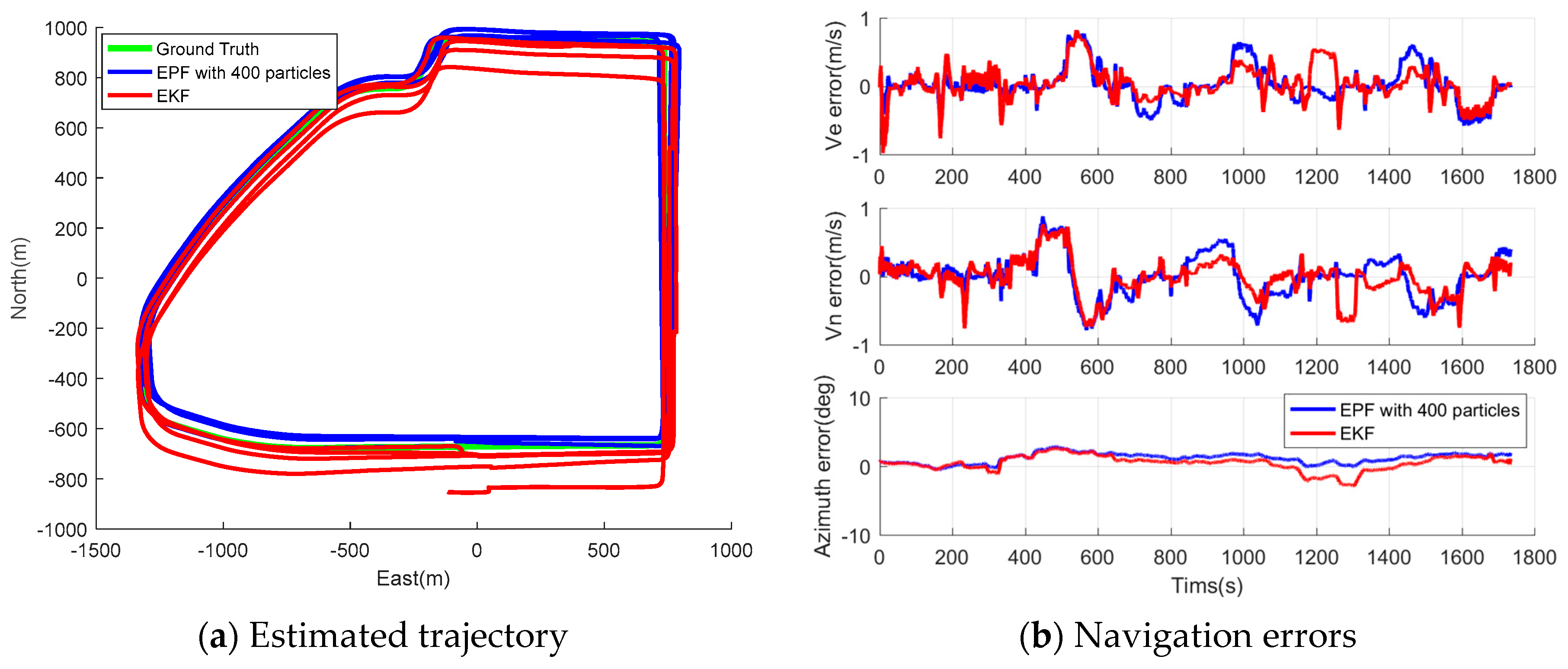

5.3.2. Positioning Performance of Wheeled INS with EPF and EKF

- Generally speaking, the estimation errors reduced as the particle number increased, along with the execution time; however, at a certain point (a particle number of 400), the reduction rate of navigation error decreased, but the calculation time still increased rapidly; therefore, 400 was chosen as the suitable particle number to implement the EPF in wheeled INS.

- The EPF outperforms the EKF in navigation solution accuracy overall; compared to the results of EKF, the RMS of horizontal position error, velocity errors, azimuth errors, and position drift rate of EPF with 400 particles are improved by 29.78%, 25.00%, 19.53%, and 29.41%, respectively, for Track II; the same figures of EPF with 400 particles are improved by 30.70%, 21.74%, 20.42%, and 12.96%, respectively, for Track III.

- Finally, the proposed wheeled INS with EPF is able to provide superior autonomous navigation solution. In the tests, the heading error and maximum position drift rate were 1.01–1.3° and 0.47–0.60%, respectively.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Observability Analysis for OD/NHC/INS

References

- Liu, S.; Yao, Z.; Cao, X.; Cai, X.; Sheng, M. Enhancing Navigation Adaptability for Ground Vehicles: Fine-Grained Urban Environment Recognition Based on GNSS Measurements. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 8509412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chan, Y.-C.; Lin, M.-C. A Novel Virtual Navigation Route Generation Scheme for Augmented Reality Car Navigation System. Sensors 2025, 25, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucco, A.; Sujit, P.B.; Aguiar, A.P.; de Sousa, J.B.; Pereira, F.L. Optimal Rendezvous Trajectory for Unmanned Aerial-Ground Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2018, 54, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Tong, S.; Zhu, G. Adaptive Fuzzy Neural Network-Aided Progressive Gaussian Approximate Filter for GPS/INS Integration Navigation. Measurement 2022, 199, 111641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaeiyan, H.; Mosavi, M.R.; Ayatollahi, A. Enhancing the Integration of the GPS/INS during GPS Outage Using LWT-IncRGRU. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsergany, A.M.; Abdel-Hafez, M.F.; Jaradat, M.A. Novel Augmented Quaternion UKF for Enhanced Loosely Coupled GPS/INS Integration. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2024, 32, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, L. Improved Robust Kalman Filter for State Model Errors in GNSS-PPP/MEMS-IMU Double State Integrated Navigation. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 67, 3156–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Fan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Shen, F.; Ming, X.; Yang, J. A Robust Adaptive Error State Kalman Filter for MEMS IMU Attitude Estimation under Dynamic Acceleration. Measurement 2025, 242, 114738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, J. A Motion Segmentation Dynamic SLAM for Indoor GNSS-Denied Environments. Sensors 2025, 25, 4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, G.; Cai, Q. Autonomous Aerial–Ground Cooperative Navigation Based on Information-Seeking in GNSS-Denied Environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 17058–17069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Chai, H.; Tian, X.; Guo, H.; Karimian, H.; Sun, J.; Dong, C. A Shipboard Integrated Navigation Algorithm Based on Smartphone Built-In GNSS/IMU/MAG Sensors. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 74, 5129–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tang, F.; Sun, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, B. Implementation of ZUPT Aided GNSS/MEMS-IMU Deeply Coupled Navigation System. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Microwave and Millimeter Wave Technology (ICMMT), Qingdao, China, 14–17 May 2023; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Soja, B.; Gao, J. Smartphone-Based Vision/MEMS-IMU/GNSS Tightly Coupled Seamless Positioning Using Factor Graph Optimization. Measurement 2024, 229, 114420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Yuan, X.; Ren, J.; Bi, Y.; Ji, X.; Zhao, S.; Wu, M.; Shen, Y. Research on Downhole MTATBOT Positioning and Autonomous Driving Strategies Based on Odometer-Assisted Inertial Measurement. Sensors 2024, 24, 7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Sun, W.; Zheng, J.; Fang, X.; Liu, J.; Mian, A. UWB–IMU–Odometer Fusion for Simultaneous Calibration and Localization. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y. A Navigation Method for IMU/Odometer Fusion Based on Horizontal Attitude Constraints. Geod. Geodyn. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, R. Multi-Sensor Integrated Navigation/Positioning Systems Using Data Fusion: From Analytics-Based to Learning-Based Approaches. Inf. Fusion 2023, 95, 102372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, J. MEMS IMU Carouseling for Ground Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2015, 64, 2242–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, J.; Kirkko-Jaakkola, M.; Takala, J. Effect of Carouseling on Angular Rate Sensor Error Processes. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2015, 64, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Sun, W.; Gao, Y. MEMS IMU Error Mitigation Using Rotation Modulation Technique. Sensors 2016, 16, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Wu, Y.; Kuang, J. Wheel-INS: A Wheel-Mounted MEMS IMU-Based Dead Reckoning System. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 9814–9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, M.; Moussa, A.; Elhabiby, M.; El-Sheimy, N. Wheel-Based Aiding of Low-Cost IMU for Land Vehicle Navigation in GNSS Challenging Environment. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 92nd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Fall), Victoria, BC, Canada, 18 November–16 December 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Niu, X. Estimate the Pitch and Heading Mounting Angles of the IMU for Land Vehicular GNSS/INS Integrated System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 6503–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Niu, X.; Kuang, J.; Liu, J. IMU Mounting Angle Calibration for Pipeline Surveying Apparatus. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yong, S.Z.; Chen, Y. Stability Control of Autonomous Ground Vehicles Using Control-Dependent Barrier Functions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2021, 6, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.H. Estimation Techniques for Low-Cost Inertial Navigation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Maybeck, P.S.; Siouris, G.M. Stochastic Models, Estimation, and Control, Volume I. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1980, 10, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, C.; Li, Z.; Zhou, F.; Liu, D. GNSS/INS/OD/NHC Adaptive Integrated Navigation Method Considering the Vehicle Motion State. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 13511–13523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshen-Meskin, D.; Bar-Itzhack, I.Y. Observability Analysis of Piece-Wise Constant Systems. II. Application to Inertial Navigation In-Flight Alignment (Military Applications). IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1992, 28, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lee, M.H.; Chun, H.-H.; Kwon, S.-H.; Speyer, J.L. Observability of Error States in GPS/INS Integration. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2005, 54, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, I.; Abdel-Hafez, M.F.; Speyer, J.L. Observability of an Integrated GPS/INS during Maneuvers. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2004, 40, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Shi, C. Observability Analysis of Non-Holonomic Constraints for Land-Vehicle Navigation Systems. In Proceedings of the 25th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS 2012), Nashville, TN, USA, 17–21 September 2012; pp. 1521–1529. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sun, S.; Sattar, T.P.; Corchado, J.M. Fight Sample Degeneracy and Impoverishment in Particle Filters: A Review of Intelligent Approaches. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 3944–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Min, H. Central Difference Particle Filter Applied to Transfer Alignment for SINS on Missiles. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2012, 48, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Miao, L.; Zhou, Z. An Improved MCMC-Based Particle Filter for GPS-Aided SINS In-Motion Initial Alignment. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 7895–7905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, L. An Opportunistic Positioning Algorithm for Internet of Vehicles under Intermittent and GNSS-Degraded Environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lou, Y.; Song, W.; Zhang, W.; Peng, Z. Performance Enhancement of PPP/SINS Tightly Coupled Navigation Based on Improved Robust Maximum Correntropy Kalman Filtering. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 74, 2078–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Lu, R.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, H.; Jiang, W. An Enhanced Smartphone GNSS/MEMS-IMU Integration Seamless Positioning Method in Urban Environments. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 41251–41263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, H.K.; Lee, H. Observability and Estimation Error Analysis of the Initial Fine Alignment Filter for Nonleveling Strapdown Inertial Navigation System. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control Trans. ASME 2013, 135, 021005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Chun, H.-H.; Kwon, S.-H.; Lee, M.H. Observability Measures and Their Application to GPS/INS. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2008, 57, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kuang, J.; Niu, X.; Stachniss, C.; Klingbeil, L.; Kuhlmann, H. Wheel-GINS: A GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation System with a Wheel-Mounted IMU. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 6891–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Our Study | Prior Wheel-Mounted IMU | OD/NHC/INS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observability analysis | Analyzed based on both observability matrix and Gramian results | Has not yet been conducted | Analyzed through covariance matrix |

| Stochastic filtering | EPF | EKF | EKF |

| Calibration of displacements | Online calibration | Manual calibration | Not applicable |

| Accl *. Bias Stability (mg) | VRW * () | Gyro Bias Stability (°/h) | ARW * () | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEMS IMU (H30) | 0.35 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.3 |

| SPAN | 0.075 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.06 |

| Time Duration (s) | Total Distance (m) | Maximum Velocity (m/s) | Average Velocity (m/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Track I | 246 | 3552 | 27.78 | 14.44 |

| Track II | 649 | 7262 | 18.47 | 11.19 |

| Track III | 1735 | 26312 | 28.85 | 15.17 |

| Uniform Linear Motion | Linear Motion with Acceleration | Circular Motion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | Eigenvector | Eigenvalue | Eigenvector | Eigenvalue | Eigenvector | |

| λ1 | 169.26 | 172.62 | {} | 172.63 | {} | |

| λ2 | 168.01 | 171.99 | {} | 90.19 | {} | |

| λ3 | 78.93 | {} | 88.05 | {} | 90.05 | {} |

| λ4 | 9.97 | {,} | 87.98 | {} | 90.01 | {} |

| λ5 | 9.21 | {,} | 87.32 | {} | 89.91 | {} |

| λ6 | 9.18 | {,} | 86.11 | {} | 89.87 | {} |

| λ7 | 9.09 | {,} | 84.60 | {} | 88.59 | {} |

| λ8 | 3.72 | {,} | 42.71 | {} | 87.03 | {} |

| λ9 | 3.66 | {,} | 41.50 | {} | 57.53 | {} |

| λ10 | 3.10 | {,} | 40.18 | {} | 55.45 | {} |

| λ11 | 3.01 | {,} | 40.09 | {} | 54.24 | {} |

| λ12 | 2.97 | {,} | 39.76 | {} | 53.14 | {} |

| λ13 | 2.72 | {,} | 39.34 | {} | 52.59 | {} |

| λ14 | 0.86 | {,} | 1.02 | {,} | 52.17 | {} |

| λ15 | 0.81 | {,} | 0.95 | {,} | 0.22 | {} |

| λ16 | 0.10 | {} | 0.12 | {} | 0.22 | {} |

| λ17 | 0.09 | {} | 0.10 | {} | 0.12 | {} |

| Positioning Metrics | Horizontal Position Error (m) | Horizontal Velocity Error (m/s) | Azimuth Error (°) | Position Drift Rate (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Rms | Max | Rms | Max | Rms | STD | Mean | ||

| Track II | Wheeled INS with comp. | 85.10 | 48.06 | 0.71 | 0.32 | 2.11 | 1.28 | 0.35 | 0.85 |

| OD/NHC/INS with comp. | 130.92 | 69.59 | 1.22 | 0.50 | 4.13 | 2.32 | 0.66 | 0.97 | |

| Track III | Wheeled INS with comp. | 100.49 | 62.41 | 1.05 | 0.46 | 2.93 | 1.42 | 0.17 | 0.54 |

| OD/NHC/INS with comp. | 337.81 | 142.04 | 4.47 | 1.94 | 17.48 | 7.70 | 0.70 | 1.01 | |

| Error Statistics | Horizontal Position Error (m) | Horizontal Velocity Error (m/s) | Azimuth Error (°) | Position Drift Rate (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Rms | Max | Rms | Max | Rms | STD | Mean | ||

| Track II | Wheeled INS without comp. | 99.34 | 53.71 | 0.88 | 0.40 | 2.58 | 1.56 | 0.51 | 0.90 |

| OD/NHC/INS without comp. | 1051.12 | 531.82 | 7.83 | 4.01 | 33.47 | 20.16 | 2.87 | 11.44 | |

| Track III | Wheeled INS without comp. | 104.77 | 64.94 | 1.11 | 0.57 | 3.29 | 1.71 | 0.38 | 0.60 |

| OD/NHC/INS without comp. | 3042.24 | 1532.702 | 53.01 | 22.48 | 179.99 | 103.99 | 6.71 | 20.41 | |

| Positioning Metrics | Horizontal Position Error | Horizontal Velocity Error | Azimuth Error | Position Drift Rate | Execution Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Rms | Max | Rms | Max | Rms | STD | Mean | (s) | |

| EPF with 100 particles | 82.12 | 46.12 | 0.63 | 0.31 | 2.08 | 1.26 | 0.34 | 0.81 | 35.80 |

| EPF with 200 particles | 72.39 | 40.44 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 1.96 | 1.16 | 0.31 | 0.71 | 37.06 |

| EPF with 300 particles | 64.43 | 35.89 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 1.82 | 1.07 | 0.28 | 0.64 | 44.42 |

| EPF with 400 particles | 60.70 | 33.75 | 0.44 | 0.24 | 1.81 | 1.03 | 0.26 | 0.60 | 57.90 |

| EPF with 500 particles | 59.51 | 33.07 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 1.81 | 1.01 | 0.25 | 0.60 | 77.51 |

| EPF with 600 particles | 58.97 | 32.76 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 1.81 | 1.01 | 0.25 | 0.59 | 103.22 |

| EKF | 85.10 | 48.06 | 0.71 | 0.32 | 2.11 | 1.28 | 0.35 | 0.85 | 13.77 |

| Positioning Metrics | Horizontal Position Error | Horizontal Velocity Error | Azimuth Error | Position Drift Rate | Execution Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Rms | Max | Rms | Max | Rms | STD | Mean | (s) | |

| EPF with 100 particles | 95.47 | 61.60 | 0.94 | 0.44 | 2.93 | 1.39 | 0.17 | 0.54 | 139.51 |

| EPF with 200 particles | 76.66 | 51.56 | 0.84 | 0.39 | 2.88 | 1.24 | 0.17 | 0.52 | 144.50 |

| EPF with 300 particles | 71.27 | 45.59 | 0.75 | 0.37 | 2.86 | 1.16 | 0.17 | 0.49 | 176.35 |

| EPF with 400 particles | 68.23 | 43.25 | 0.71 | 0.36 | 2.85 | 1.13 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 226.39 |

| EPF with 500 particles | 67.12 | 42.56 | 0.70 | 0.36 | 2.85 | 1.13 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 306.16 |

| EPF with 600 particles | 66.65 | 42.30 | 0.70 | 0.36 | 2.85 | 1.13 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 411.85 |

| EKF | 100.49 | 62.41 | 1.05 | 0.46 | 2.93 | 1.42 | 0.17 | 0.54 | 53.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, S.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q. An Autonomous Land Vehicle Navigation System Based on a Wheel-Mounted IMU. Sensors 2026, 26, 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010328

Du S, Sun W, Wang X, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Li Q. An Autonomous Land Vehicle Navigation System Based on a Wheel-Mounted IMU. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010328

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Shuang, Wei Sun, Xin Wang, Yuyang Zhang, Yongxin Zhang, and Qihang Li. 2026. "An Autonomous Land Vehicle Navigation System Based on a Wheel-Mounted IMU" Sensors 26, no. 1: 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010328

APA StyleDu, S., Sun, W., Wang, X., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., & Li, Q. (2026). An Autonomous Land Vehicle Navigation System Based on a Wheel-Mounted IMU. Sensors, 26(1), 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010328