CW-DETR: An Efficient Detection Transformer for Traffic Signs in Complex Weather

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

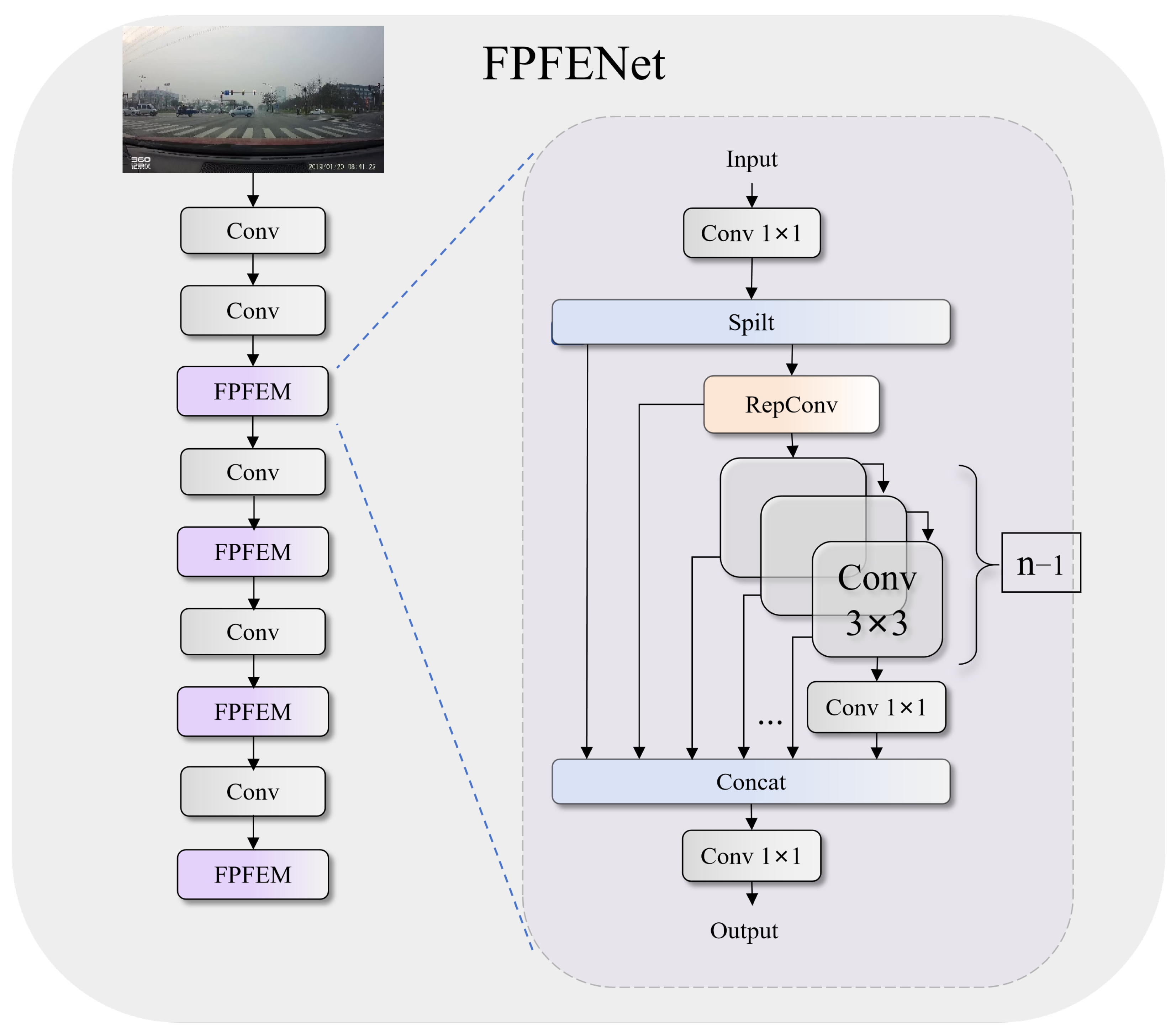

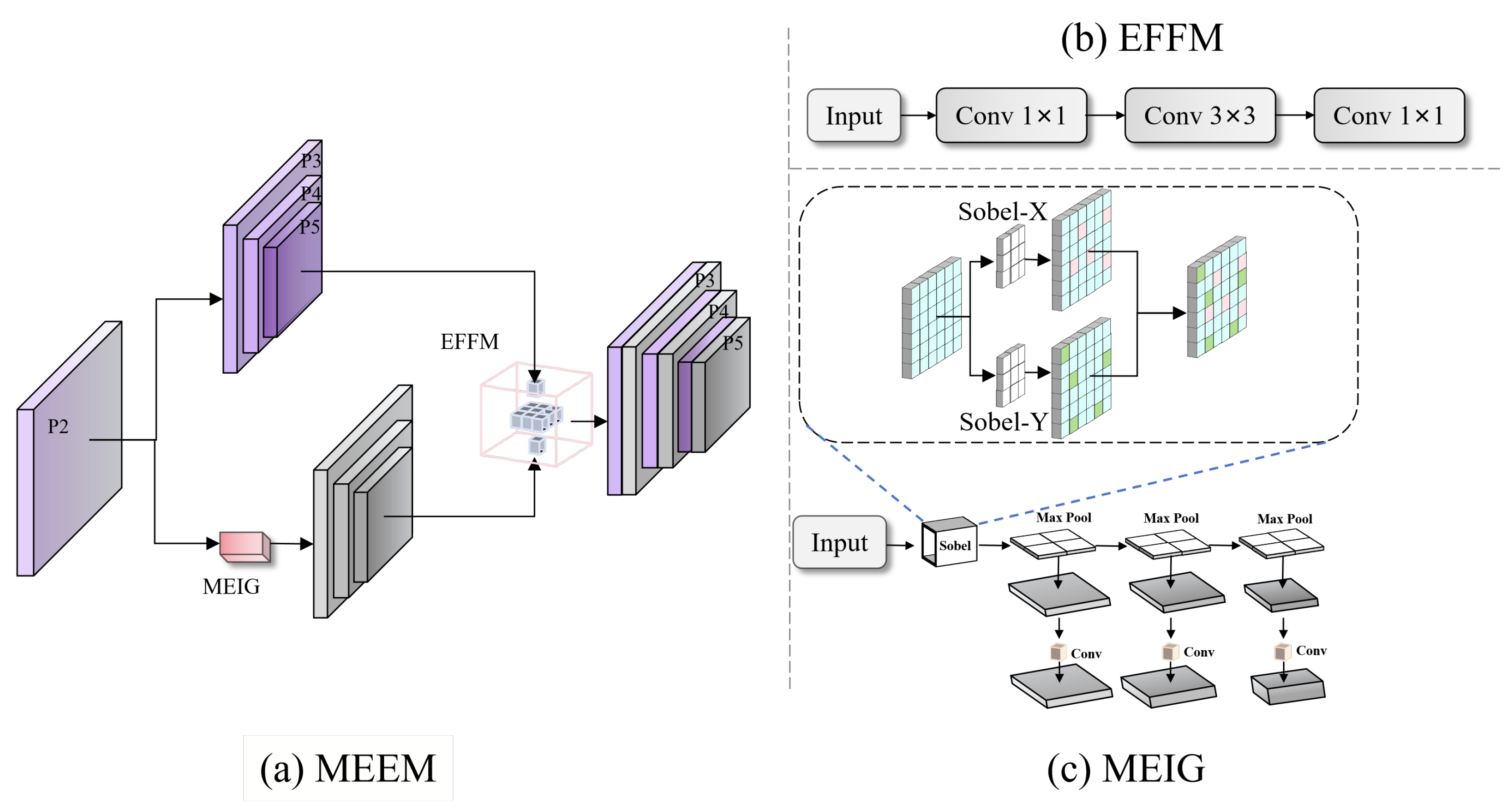

- We propose two complementary modules: the fused path feature enhancement module (FPFEM) preserves fine-grained texture features through multipath feature transformation and reparameterization, while the Multiscale Edge Enhancement Mechanism (MEEM) enhances boundary information via channel-decoupled edge extraction. Together, they address texture blurring and edge degradation under adverse weather conditions.

- (2)

- We construct the Adaptive Dual-Branch Bidirectional Fusion Feature Pyramid Network (ADBF-FPN) for cross-scale feature compensation through bidirectional feature flow and adaptive weighted fusion, and design the multiscale convolutional gating module (MCGM) to selectively suppress weather-induced noise by using partial convolution and gated filtering. These modules jointly improve the multiscale detection robustness.

- (3)

- On CCTSDB2021, the CW-DETR achieves 69.0% and 94.4% , outperforming the baseline by 5.7 and 4.5 percentage points respectively, while reducing parameters by 15%. Cross-dataset experiments on TT100K, the TSRD, CNTSSS, and real-world snow conditions validate the generalizability of the model.

2. Related Work

2.1. Object Detection Algorithms

2.2. RT-DETR Framework

3. Method Overview

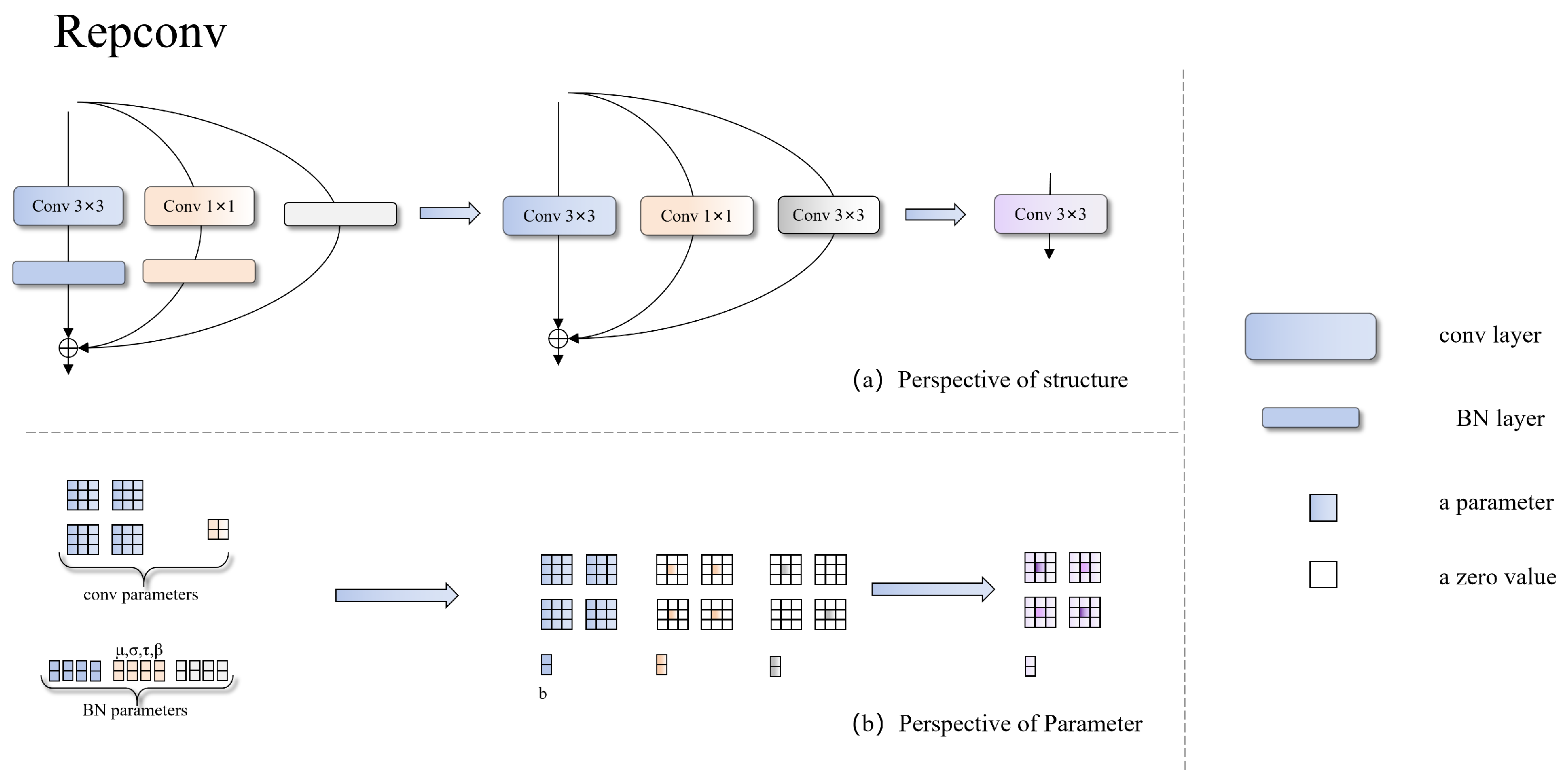

3.1. Multipath Feature Enhancement Backbone

3.2. Multiscale Edge Enhancement Mechanism

3.2.1. MEIG

3.2.2. EFFM

3.3. Adaptive Dual-Branch Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network

Fusion Module

3.4. Multiscale Gated Filtering Mechanism

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Experimental Details

4.2.1. Experimental Environment

4.2.2. Evaluation Metrics

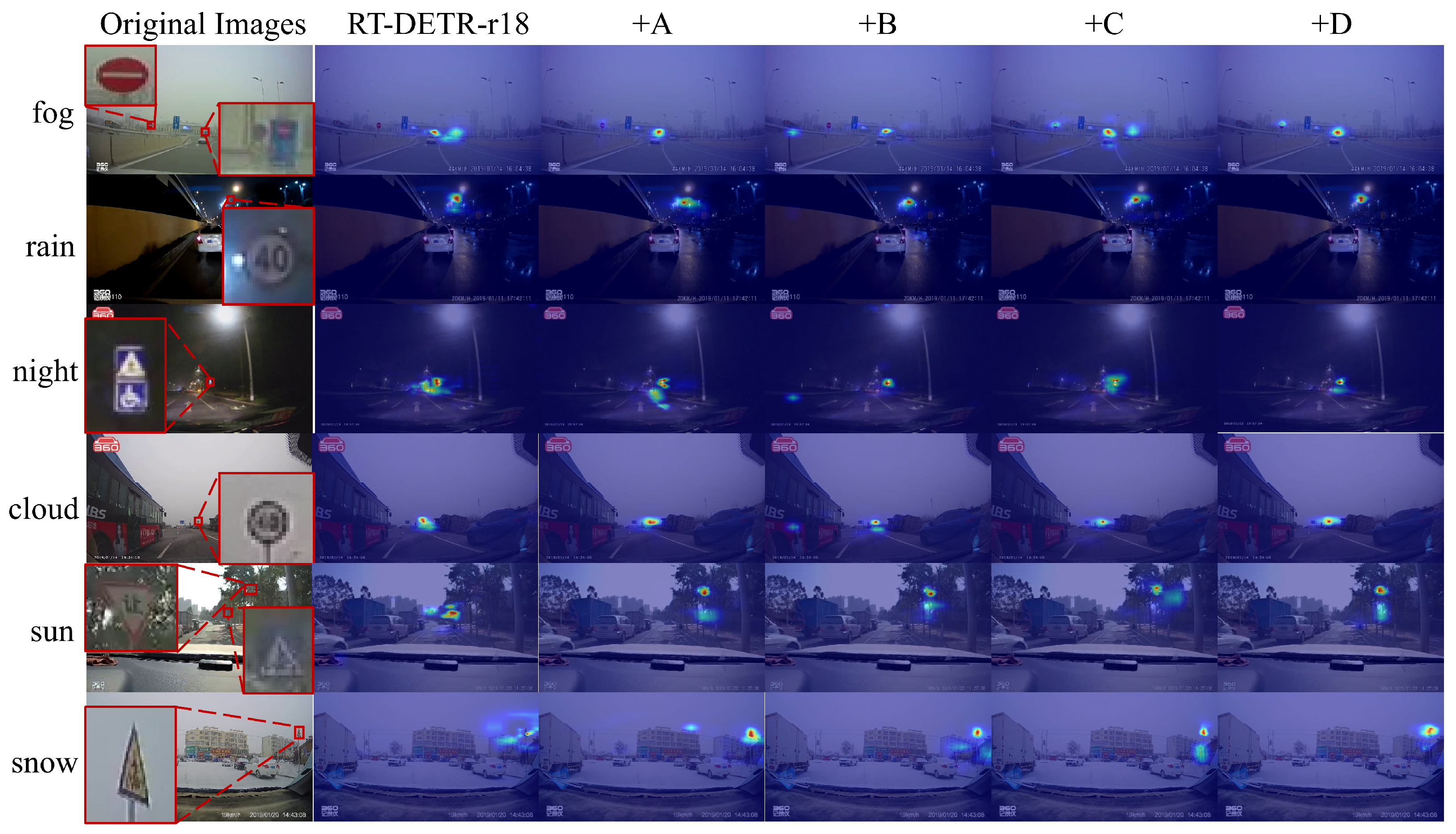

4.3. Ablation Study

4.4. Comparative Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeng, G.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; E, W. Transformer fusion and residual learning group classifier loss for long-tailed traffic sign detection. IEEE Sensors J. 2024, 24, 10551–10560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenk, M.A.; Hassaballah, M. DAWN: Vehicle detection in adverse weather nature dataset. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.05402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaridis, C.; Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. Semantic foggy scene understanding with synthetic data. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2018, 126, 973–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelic, M.; Gruber, T.; Mannan, F.; Kraus, F.; Ritter, W.; Dietmayer, K.; Heide, F. Seeing through fog without seeing fog: Deep multimodal sensor fusion in unseen adverse weather. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11682–11692. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; Changyu, L.; Hogan, A.; Diaconu, L.; Poznanski, J.; Yu, L.; Rai, P.; Ferriday, R.; et al. ultralytics/yolov5: V3.0.; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan, S.G.; Nayar, S.K. Vision and the atmosphere. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2002, 48, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindagi, V.A.; Oza, P.; Yasarla, R.; Patel, V.M. Prior-based domain adaptive object detection for hazy and rainy conditions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 763–780. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, M.; Hu, S.; Liu, H. DeMatchNet: A Unified Framework for Joint Dehazing and Feature Matching in Adverse Weather Conditions. Electronics 2025, 14, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, Y.; Shoji, Y.; Toizumi, T.; Ito, A. ERUP-YOLO: Enhancing Object Detection Robustness for Adverse Weather Condition by Unified Image-Adaptive Processing. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 8597–8605. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, M.; Wang, M.; Zhao, F.; Guo, J. Multiscale traffic sign detection method in complex environment based on YOLOv4. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 5297605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Yang, X.; Zhou, H.; Xie, Y. Improved YOLOv5-based for small traffic sign detection under complex weather. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandnani, M.; Shukla, S.; Wadhvani, R. Multistage traffic sign recognition under harsh environment. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 80425–80457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoob, S.; Kumar, D.P.; Harshitha, G.; Teja, V.S.; Veni, C.S.; Reddy, K.M. Enhancing Object Detection Robustness In Adverse Weather Conditions. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 252, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, X.; Hu, P.; Wu, Z.; Lv, J.; Peng, X. All-in-one image restoration for unknown corruption. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17452–17462. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, D.; Wang, X.; Bai, X.; Liu, W. Traffic sign detection and recognition using fully convolutional network guided proposals. Neurocomputing 2016, 214, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dai, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Hu, X.; Lu, T.; Lu, L.; Li, H.; et al. Internimage: Exploring large-scale vision foundation models with deformable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 14408–14419. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, R.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Y. Feature aggregation network for small object detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Dey, S.; Shah, M.; Gupta, S. Traffic sign detection in unconstrained environment using improved YOLOv4. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Arcos-García, Á.; Alvarez-Garcia, J.A.; Soria-Morillo, L.M. Deep neural network for traffic sign recognition systems: An analysis of spatial transformers and stochastic optimisation methods. Neural Netw. 2018, 99, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yan, W.Q. Traffic sign recognition based on deep learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 17779–17791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.R.; Lee, C.P.; Lim, K.M.; Ong, T.S.; Alqahtani, A.; Ali, M. Recent advances in traffic sign recognition: Approaches and datasets. Sensors 2023, 23, 4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable detr: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Guan, Q.; Zhao, K.; Yang, J.; Xu, X.; Long, H.; Tang, Y. Multi-branch auxiliary fusion yolo with re-parameterization heterogeneous convolutional for accurate object detection. In Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV), Urumqi, China, 18–20 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 492–505. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, J.; Du, S.; Ying, S.; Yong, J.H.; Li, Y.; Ding, G.; Ji, R.; Gao, Y. Hyper-yolo: When visual object detection meets hypergraph computation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 47, 2388–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.; Halder, S.S.; De Charette, R.; Lalonde, J.F. Rain rendering for evaluating and improving robustness to bad weather. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Fu, X.; Zha, Z.J. Edge-aware regional message passing controller for image forgery localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 8222–8232. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Gelernter, J.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Yu, Y. Traffic sign detection using a multi-scale recurrent attention network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 4466–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ye, Z.; Jin, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Real-time traffic sign detection based on multiscale attention and spatial information aggregator. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2022, 19, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, Z.; Sun, J.; Zou, X.; Wang, J. A cascaded R-CNN with multiscale attention and imbalanced samples for traffic sign detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 29742–29754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Lu, C.; Wang, J.; Sangaiah, A.K. Lightweight deep network for traffic sign classification. Ann. Telecommun. 2020, 75, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.h.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.H.; Chan, S.H.G. Run, don’t walk: Chasing higher FLOPS for faster neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 12021–12031. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zou, X.; Kuang, L.D.; Wang, J.; Sherratt, R.S.; Yu, X. CCTSDB 2021: A more comprehensive traffic sign detection benchmark. Hum.-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Xie, X.; Gui, Y.; Kim, G.J. ReYOLO: A traffic sign detector based on network reparameterization and features adaptive weighting. J. Ambient Intell. Smart Environ. 2022, 14, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liang, D.; Zhang, S.; Huang, X.; Li, B.; Hu, S. Traffic-sign detection and classification in the wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2110–2118. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Wu, J.; Yin, G.; Lin, L. YOLO-LLTS: Real-Time Low-Light Traffic Sign Detection via Prior-Guided Enhancement and Multi-Branch Feature Interaction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Param | GFLOPs | AP | FPS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-DETR-R18 | 19,875,612 | 56.9 | 63.3 | 89.9 | 76.6 | 61.8 | 70.4 | - | 64.6 |

| +A | 13,847,100 | 44.5 | 65.5 | 90.9 | 81.0 | 64.4 | 70.6 | - | 104.4 |

| +B | 21,809,756 | 63.2 | 60.9 | 92.1 | 72.8 | 56.7 | 71.6 | - | 58.2 |

| +C | 20,108,141 | 57.5 | 62.8 | 90.3 | 74.3 | 62.8 | 64.8 | - | 65.4 |

| +D | 19,511,456 | 51.4 | 64.8 | 90.7 | 80.2 | 62.9 | 71.6 | - | 70.7 |

| +A+B | 15,900,540 | 52.2 | 64.8 | 92.2 | 79.6 | 64.1 | 68.8 | - | 76.8 |

| +A+C | 14,173,837 | 46.3 | 63.1 | 91.1 | 75.5 | 61.1 | 70.2 | - | 70.7 |

| +A+B+C | 16,473,037 | 54.6 | 65.0 | 91.4 | 76.5 | 62.9 | 72.9 | - | 74.6 |

| +A+B+C+D | 16,883,149 | 56.8 | 69.0 | 94.4 | 81.4 | 68.3 | 73.4 | - | 67.7 |

| Model | BG→0 | BG→1 | BG→2 | MCA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-DETR-R18 | 0.38 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 89.3% |

| +A (FPFENet) | 0.17 | 0.71 | 0.12 | 0.84 | 91.7% |

| +B (MEEM) | 0.27 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.84 | 90.7% |

| +C (ADBF-FPN) | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 0.84 | 90.7% |

| +D (MCGM) | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.77 | 86.3% |

| CW-DETR | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 95.0% |

| Model | Param | GFLOPs | FPS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-time Detectors | |||||||||

| YOLOv5m | 21,496,969 | 54.9 | 55.5 | 81.9 | 65.2 | 51.8 | 68.3 | - | 103.4 |

| YOLOv5l | 53,133,721 | 134.7 | 58.5 | 82.6 | 69.3 | 56.3 | 66.8 | - | 46.7 |

| YOLOv8m | 25,858,057 | 79.1 | 60.1 | 85.0 | 70.7 | 59.4 | 65.2 | - | 79.8 |

| YOLOv8l | 43,608,921 | 164.8 | 60.3 | 84.9 | 72.3 | 57.3 | 71.3 | - | 33.2 |

| YOLOv10m | 15,314,905 | 58.9 | 50.8 | 74.2 | 60.0 | 47.0 | 64.4 | - | 105.2 |

| YOLOv10l | 24,311,641 | 120 | 50.5 | 73.1 | 60.1 | 46.9 | 63.8 | - | 38.3 |

| YOLOv11m | 20,032,345 | 67.7 | 58.5 | 83.7 | 69.9 | 55.8 | 66.7 | - | 90.1 |

| YOLOv11l | 25,281,625 | 86.6 | 57.7 | 83.0 | 71.6 | 54.7 | 69.4 | - | 40.9 |

| Hyper-YOLO | 358,887 | 9.5 | 51.1 | 75.9 | 60.0 | 47.0 | 68.4 | - | 272.1 |

| End-to-end Object Detectors | |||||||||

| AlignDETR | - | - | 69.6 | 94.1 | 84.7 | 69.3 | 71.8 | - | - |

| Deformable DETR | - | - | 62.2 | 63.4 | 75.5 | 60.8 | 68.4 | - | - |

| Real-time End-to-end Object Detectors | |||||||||

| RT-DETR-R18 | 19,875,612 | 56.9 | 63.3 | 89.9 | 76.6 | 61.8 | 70.4 | - | 64.6 |

| RT-DETR-R34 | 31,109,315 | 88.8 | 62.5 | 90.9 | 72.4 | 61.2 | 67.9 | - | 45.9 |

| RT-DETR-R50 | 41,960,273 | 129.6 | 65.4 | 92.3 | 83.2 | 64.7 | 69.6 | - | 36.6 |

| RT-DETR-R50-m | 36,257,105 | 96.1 | 64.3 | 92.0 | 76.9 | 63.2 | 70.9 | - | 40.3 |

| RT-DETR-l | 31,990,161 | 103.4 | 64.7 | 89.9 | 78.4 | 63.1 | 70.1 | - | 54.2 |

| CW-DETR | 16,883,149 | 56.8 | 69.0 | 94.4 | 81.4 | 68.3 | 73.4 | - | 67.7 |

| DATA | Model | AP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCTSDB2021 | RT-DETR-R18 | 63.3 | 89.9 | 76.6 | 61.8 | 70.4 | - |

| CW-DETR | 69.0 | 94.4 | 81.4 | 68.3 | 73.4 | - | |

| TT100K | RT-DETR-R18 | 63.8 | 78.5 | 74.7 | 52.6 | 65.7 | 75.3 |

| CW-DETR | 67.7 | 83.0 | 81.0 | 55.7 | 69.7 | 80.9 | |

| TSRD | RT-DETR-R18 | 88.0 | 94.4 | 94.2 | 60.5 | 88.2 | 87.8 |

| CW-DETR | 88.4 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 58.6 | 88.6 | 89.0 |

| Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| RT-DETR-R18 | warning | 37.1 |

| mandatory | 80.3 | |

| CW-DETR | warning | 61.8 |

| mandatory | 90.2 |

| Model | Condition | AP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-DETR-R18 | nightfall | 0.414 | 0.635 | 0.447 | 0.277 | 0.410 | - |

| night | 0.351 | 0.572 | 0.389 | 0.246 | 0.424 | - | |

| no light | 0.212 | 0.417 | 0.183 | 0.189 | 0.238 | - | |

| rain | 0.282 | 0.454 | 0.299 | 0.192 | 0.323 | - | |

| CW-DETR | nightfall | 0.438 | 0.675 | 0.488 | 0.303 | 0.431 | - |

| night | 0.371 | 0.586 | 0.424 | 0.292 | 0.431 | - | |

| no light | 0.231 | 0.460 | 0.205 | 0.191 | 0.267 | - | |

| rain | 0.305 | 0.473 | 0.347 | 0.243 | 0.334 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Teng, Q.; Sun, S.; Song, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. CW-DETR: An Efficient Detection Transformer for Traffic Signs in Complex Weather. Sensors 2026, 26, 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010325

Wang T, Teng Q, Sun S, Song W, Zhang J, Li Y. CW-DETR: An Efficient Detection Transformer for Traffic Signs in Complex Weather. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):325. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010325

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tianpeng, Qiaoshuang Teng, Shangyu Sun, Weidong Song, Jinhe Zhang, and Yuxuan Li. 2026. "CW-DETR: An Efficient Detection Transformer for Traffic Signs in Complex Weather" Sensors 26, no. 1: 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010325

APA StyleWang, T., Teng, Q., Sun, S., Song, W., Zhang, J., & Li, Y. (2026). CW-DETR: An Efficient Detection Transformer for Traffic Signs in Complex Weather. Sensors, 26(1), 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010325