Current-Aware Temporal Fusion with Input-Adaptive Heterogeneous Mixture-of-Experts for Video Deblurring

Abstract

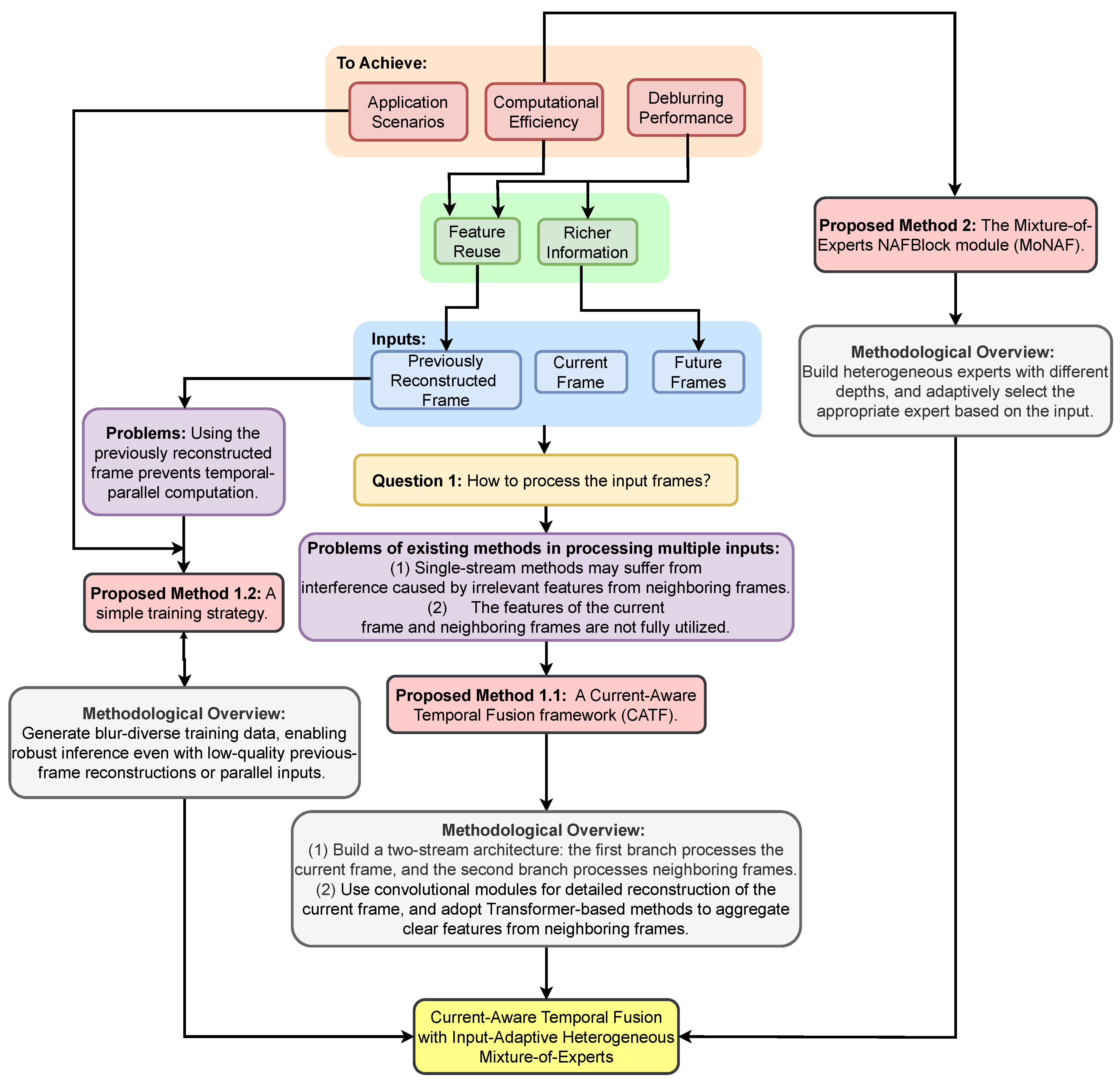

1. Introduction

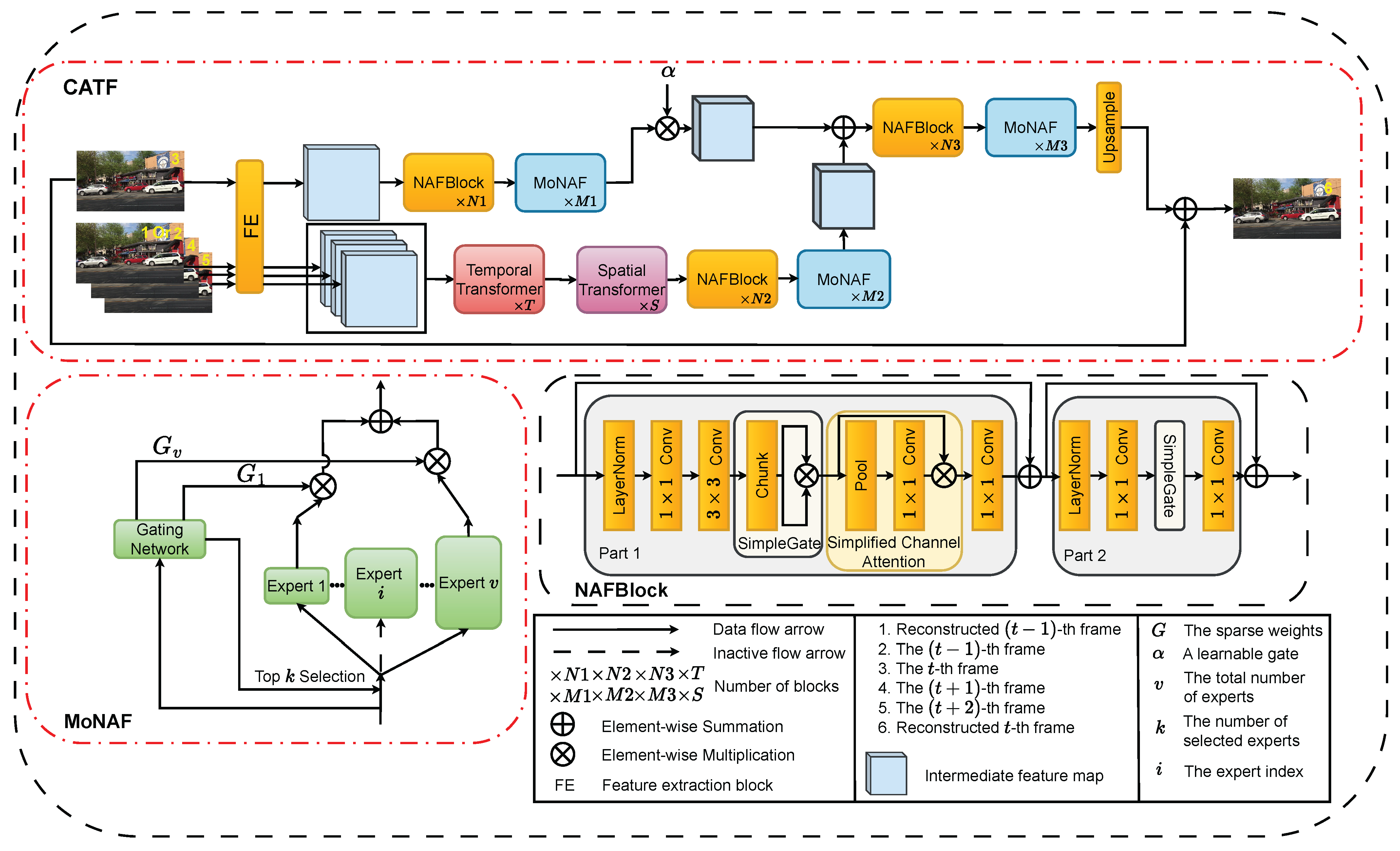

- To address the issues of insufficient utilization of the current frame and the interference from irrelevant features of neighboring frames in single-stream structures, this paper proposes a current-aware temporal fusion framework. A simple training strategy is used to achieve reasonable performance in both sequential and parallel computation.

- Considering the varying blur in video frames, this paper proposes a Mixture-of-Experts structure with shallow, medium, and deep modules, achieving high deblurring quality while reducing the inference time.

- Qualitative and quantitative experiments demonstrate that our algorithm performs well in both deblurring quality and inference speed in sequential computation. Furthermore, experiments confirm that the proposed framework exhibits minimal error accumulation during sequential inference and achieves satisfactory results in temporal parallel computation.

2. Related Work

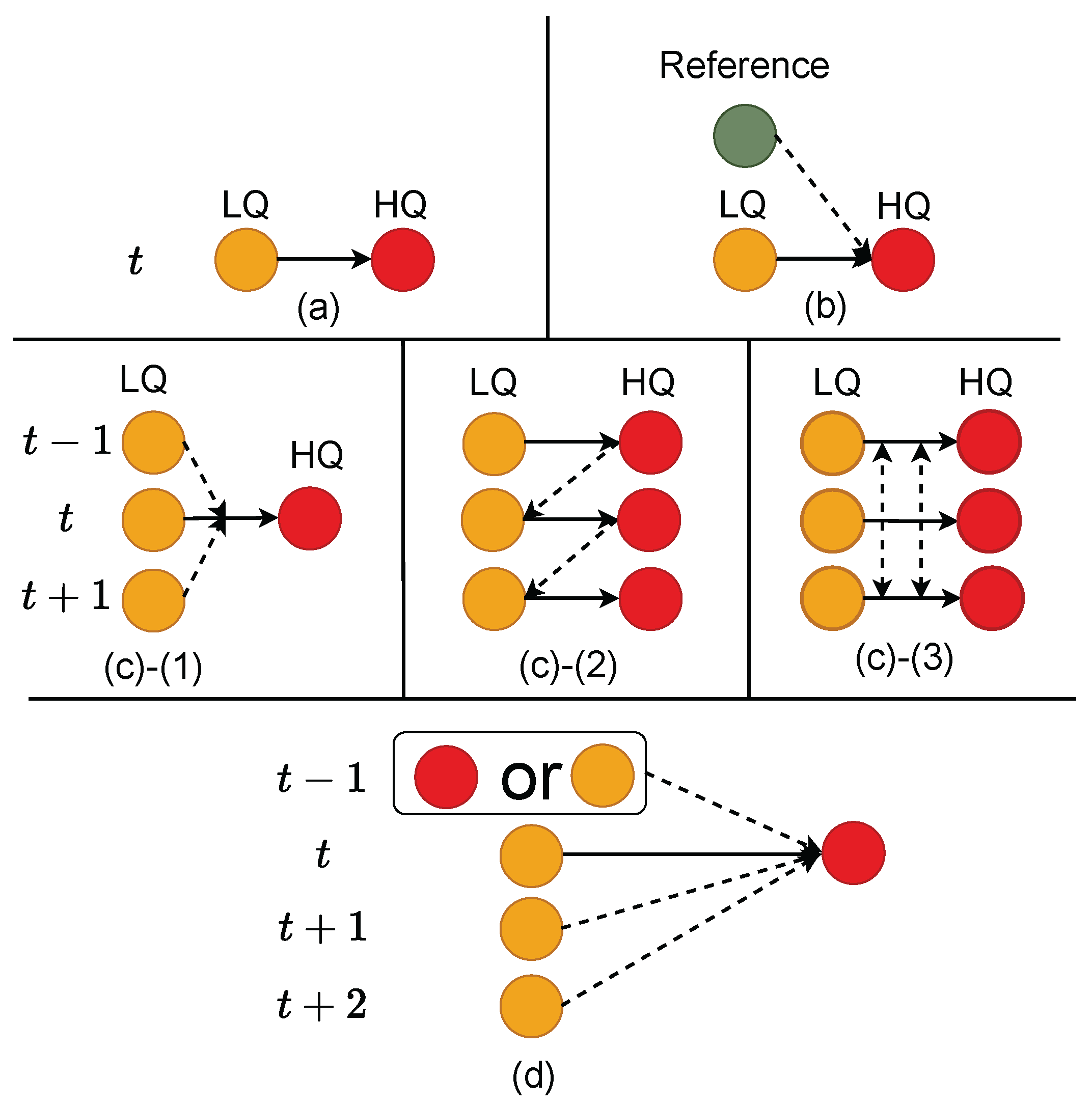

2.1. Video Deblurring Methods

2.2. Temporal Fusion

3. Proposed Methods

3.1. The Current-Aware Temporal Fusion Framework

3.2. The Mixture-of-Experts Module Based on NAFBlocks

3.3. The Training Strategy

3.4. Loss Function

3.4.1. Reconstruction Loss

3.4.2. Perceptual Loss

3.4.3. MoE Loss

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Datasets and Setting

4.2. Comparison with Video Deblurring Methods

4.2.1. Quantitative Comparison

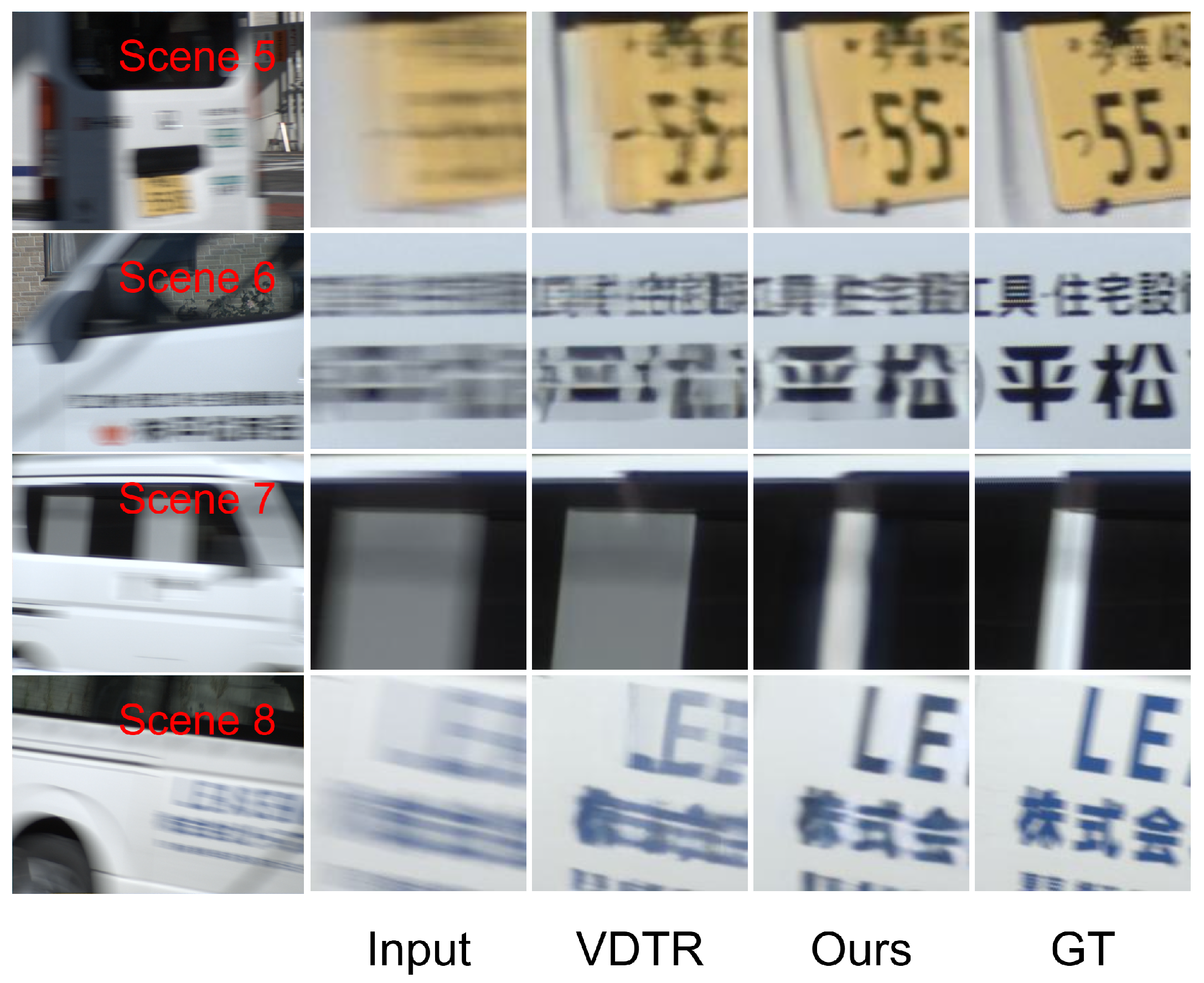

4.2.2. Qualitative Comparison

4.3. Evaluation of Error Accumulation Mitigation and Parallelism

4.4. Ablation Experiment

4.5. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, Y.J.; Hsu, M.C.; Liang, W.Y. Image Sensing for Motorcycle Active Safety Warning System: Using YOLO and Heuristic Weighting Mechanism. Sensors 2025, 25, 7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsamenis, I.; Bakalos, N.; Lappas, A.; Protopapadakis, E.; Martín-Portugués Montoliu, C.; Doulamis, A.; Doulamis, N.; Rallis, I.; Kalogeras, D. DORIE: Dataset of Road Infrastructure Elements—A Benchmark of YOLO Architectures for Real-Time Patrol Vehicle Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Yuan, H.; Zhao, S.; Tian, W.; Han, D.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, S. Deep Learning-Based Instance Segmentation of Galloping High-Speed Railway Overhead Contact System Conductors in Video Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, C.; Sun, F.; Li, Z.; Xie, Y. Deep learning in motion deblurring: Current status, benchmarks and future prospects. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 3801–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Wan, Z.; Dai, Y.; Yu, X. Deep idempotent network for efficient single image blind deblurring. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 33, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chu, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Simple baselines for image restoration. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Cheung, K.C.; Wang, X.; Qin, H.; Li, H. Learning degradation representations for image deblurring. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 736–753. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, D.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Reid, I.; Shen, C.; van den Hengel, A.; Shi, Q. From Motion Blur to Motion Flow: A Deep Learning Solution for Removing Heterogeneous Motion Blur. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2319–2328. [Google Scholar]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H.; Shao, L. Multi-stage progressive image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 14821–14831. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.J.; Ji, S.W.; Hong, J.P.; Jung, S.W.; Ko, S.J. Rethinking coarse-to-fine approach in single image deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 4641–4650. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ji, Z.; Chen, W.; Peng, Y. Lightweight MIMO-WNet for single image deblurring. Neurocomputing 2023, 516, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hua, Z.; Li, J. Reference-based dual-task framework for motion deblurring. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Suganuma, M.; Okatani, T. Reference-based motion blur removal: Learning to utilize sharpness in the reference image. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.02875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pan, J.; Luo, Y.; Lu, J. Deep ranking exemplar-based dynamic scene deblurring. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 2245–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yang, H.; Fu, J.; Lu, H.; Guo, B. Learning texture transformer network for image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 5791–5800. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Dong, H.; Pan, J.; Liang, B.; Huang, Y.; Fu, L.; Wang, F. Deep recurrent neural network with multi-scale bi-directional propagation for video deblurring. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 3598–3607. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, B. Efficient spatio-temporal recurrent neural network for video deblurring. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, B.; Yao, A. Multi-scale memory-based video deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 1919–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Fan, Y.; Li, S.; Qian, X. Decoupling degradations with recurrent network for video restoration in under-display camera. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 3558–3566. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, H.; Yao, H. Spatio-temporal deformable attention network for video deblurring. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 581–596. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, M.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. VDTR: Video Deblurring with Transformer. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chan, K.C.; Yu, K.; Dong, C.; Change Loy, C. Edvr: Video restoration with enhanced deformable convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16-17 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Ranjan, R.; Li, Y.; Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. Vrt: A video restoration transformer. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 2171–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, B.; Yang, Z.; Pan, J. Deblurring Videos Using Spatial-Temporal Contextual Transformer with Feature Propagation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 6354–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, J.; Lee, J.; Park, E. Frdiff: Feature reuse for universal training-free acceleration of diffusion models. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 328–344. [Google Scholar]

- Boucherit, I.; Kheddar, H. Reinforced Residual Encoder–Decoder Network for Image Denoising via Deeper Encoding and Balanced Skip Connections. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2025, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, C.; Lu, X. Improving image restoration by revisiting global information aggregation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Chan, Y.L.; Kwong, N.W.; Tsang, S.H.; Lam, K.M.; Ling, W.K. Long short-term fusion by multi-scale distillation for screen content video quality enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 7762–7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.A.; Jordan, M.I.; Nowlan, S.J.; Hinton, G.E. Adaptive mixtures of local experts. Neural Comput. 1991, 3, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Wei, H.; Pan, J. Deep video deblurring using sharpness features from exemplars. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 8976–8987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zheng, N.; Huang, J.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, F. Learning spatio-temporal sharpness map for video deblurring. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 34, 3957–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wei, G.; Liu, K.; Feng, W.; Zhao, T. LightViD: Efficient Video Deblurring with Spatial–Temporal Feature Fusion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 7430–7439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Van Gool, L. Video super-resolution transformer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.06847. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Jiang, R.; Zhao, L.; Xu, Y. Multi-attention convolutional neural network for video deblurring. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 32, 1986–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, C.; Zhang, K.; Yu, X.; Zhong, Y.; Ren, W.; Suominen, H.; Li, H. Arvo: Learning all-range volumetric correspondence for video deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7721–7731. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.; Delbracio, M.; Wang, J.; Sapiro, G.; Heidrich, W.; Wang, O. Deep Video Deblurring for Hand-Held Cameras. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.Y.; Wong, W.K.; Woo, W.c. Convolutional LSTM network: A machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 802–810. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J.; Xie, H.; Zuo, W.; Ren, J. Spatio-temporal filter adaptive network for video deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 2482–2491. [Google Scholar]

- Son, H.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Cho, S.; Lee, S. Recurrent video deblurring with blur-invariant motion estimation and pixel volumes. ACM Trans. Graph. 2021, 40, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Hu, X.; Luo, D.; Tai, Y.; Wang, C.; Qian, Y. Efficiently exploiting spatially variant knowledge for video deblurring. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 12581–12593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Kim, S. How do vision transformers work? arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.06709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazeer, N.; Mirhoseini, A.; Maziarz, K.; Davis, A.; Le, Q.; Hinton, G.; Dean, J. Outrageously large neural networks: The sparsely-gated mixture-of-experts layer. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.06538. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Nah, S.; Hyun Kim, T.; Mu Lee, K. Deep multi-scale convolutional neural network for dynamic scene deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3883–3891. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.; Bai, H.; Tang, J. Cascaded deep video deblurring using temporal sharpness prior. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 3043–3051. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Cai, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Yan, Y.; Zou, X.; Ding, H.; Zhang, Y.; Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. Flow-guided sparse transformer for video deblurring. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.01893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xiong, R.; Fan, X.; Zhao, D. Attentive Large Kernel Network With Mixture of Experts for Video Deblurring. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 5575–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; You, J. Peak signal-to-noise ratio revisited: Is simple beautiful? In Proceedings of the 2012 Fourth International Workshop on Quality of Multimedia Experience, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 5–7 July 2012; pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chan, K.C.; Loy, C.C. Exploring clip for assessing the look and feel of images. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; pp. 2555–2563. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Sliding Window-Based | Fuses temporal information across frames | Limits feature reuse across frames; restricts long-range modeling due to window size |

| Recurrent | Shares parameters across frames; supports feature reuse; fuses temporal information across frames | Cannot perform parallel computation; accumulates errors over time; limits long-range modeling; performs poorly on few-frame videos [33] |

| Parallel | Supports multi-frame parallel processing; fuses temporal information across frames; supports feature reuse | Requires a large model; consumes high memory; constrains scalability by hardware resources |

| Dataset | DVD | GoPro | BSD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Val | Test | |

| Videos | 61 | 10 | 22 | 11 | 60 | 20 | 20 |

| Frames | 5708 | 1000 | 2103 | 1111 | 6000 | 2000 | 3000 |

| Component | Setting |

|---|---|

| Data augmentation | Random crop (256 × 256), horizontal flips, vertical flips |

| Optimizer | ADAM |

| ADAM parameters | , |

| Initial learning rate | (DVD and GoPro) (BSD) |

| Epoch | 2000 |

| Batch size | 5 |

| Metric | STFAN | CDVDTSP | FGST | STDANet | VDTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | 31.15 | 32.13 | 33.50 | 33.05 | 33.13 |

| SSIM | 0.9049 | 0.9268 | 0.945 | 0.9374 | 0.9359 |

| Metric | LightVID | STCT | ALK-MoE | Ours | |

| PSNR | 32.51 | 33.45 | 33.63 | 33.54 | |

| SSIM | 0.946 | 0.9421 | 0.9448 | 0.9430 |

| Metric | STFAN | CDVDTSP | FGST | STDANet | VDTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | 28.59 | 31.67 | 33.02 | 32.62 | 33.15 |

| SSIM | 0.8608 | 0.9279 | 0.947 | 0.9375 | 0.9402 |

| Metric | LightVID | STCT | ALK-MoE | Ours | |

| PSNR | 32.73 | 32.97 | 33.79 | 33.56 | |

| SSIM | 0.941 | 0.9406 | 0.9516 | 0.9477 |

| Method | 1 ms–8 ms | 3 ms–24 ms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | |

| STFAN | 32.78 | 0.9219 | 29.47 | 0.8716 |

| EDVR | 33.16 | 0.9325 | 31.93 | 0.9261 |

| CDVDTSP | 33.54 | 0.9415 | 31.58 | 0.9258 |

| VDTR | 34.12 | 0.9436 | 32.53 | 0.9363 |

| ALK-MoE | 35.12 | 0.9505 | 33.42 | 0.9372 |

| Ours | 34.56 | 0.9486 | 33.09 | 0.9453 |

| Method | GFLOPs (G) | Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| FGST | 2075.1 | 1011.9 |

| VDTR | 2244.7 | 266.7 |

| STCT | 44,620.5 | 1239.0 |

| ALK-MoE | 1650.0 | – |

| Ours | 1352.1 | 198.8 |

| Group | Previous-Frame Deblurred Result (Preparation Phase, 4 Frames) Replaced with | Previous-Frame Deblurred Result (Actual Phase) Replaced with | PSNR | SSIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | GT | Deblurred result | 33.56 | 0.9477 |

| Group 2 | Previous frame | Deblurred result | 33.53 | 0.9475 |

| Group 3 | GT | GT | 33.78 | 0.9492 |

| Group 4 | Previous frame | Previous frame | 32.61 | 0.9378 |

| Method | PSNR | SSIM |

|---|---|---|

| CATF (Current-frame reconstruction and w/o MoNAF) | 31.82 | 0.9262 |

| CATF (w/o MoNAF) (Reconstruct ) | 33.11 | 0.9432 |

| CATF (w/o MoNAF) (Reconstruct ) | 33.19 | 0.9438 |

| Type | The Numbers of MoE | Expert 1 | Expert 2 | Expert 3 | PSNR | SSIM | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | None | None | None | None | 33.11 | 0.9432 | 5.40 |

| Homogeneous | 3 | Part 1 | Part 1 | Part 1 | 33.29 | 0.9456 | 4.77 |

| Homogeneous | 3 | 2 Part 1 | 2 Part 1 | 2 Part 1 | 33.38 | 0.9466 | 4.56 |

| Heterogeneous | 3 | Part 1 | Part 2 | NAFBlock | 33.31 | 0.9456 | 4.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Namiki, A. Current-Aware Temporal Fusion with Input-Adaptive Heterogeneous Mixture-of-Experts for Video Deblurring. Sensors 2026, 26, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010321

Zhang Y, Zhao Z, Namiki A. Current-Aware Temporal Fusion with Input-Adaptive Heterogeneous Mixture-of-Experts for Video Deblurring. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010321

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yanwen, Zejing Zhao, and Akio Namiki. 2026. "Current-Aware Temporal Fusion with Input-Adaptive Heterogeneous Mixture-of-Experts for Video Deblurring" Sensors 26, no. 1: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010321

APA StyleZhang, Y., Zhao, Z., & Namiki, A. (2026). Current-Aware Temporal Fusion with Input-Adaptive Heterogeneous Mixture-of-Experts for Video Deblurring. Sensors, 26(1), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010321