MIGS: A Modular Edge Gateway with Instance-Based Isolation for Heterogeneous Industrial IoT Interoperability

Abstract

1. Introduction

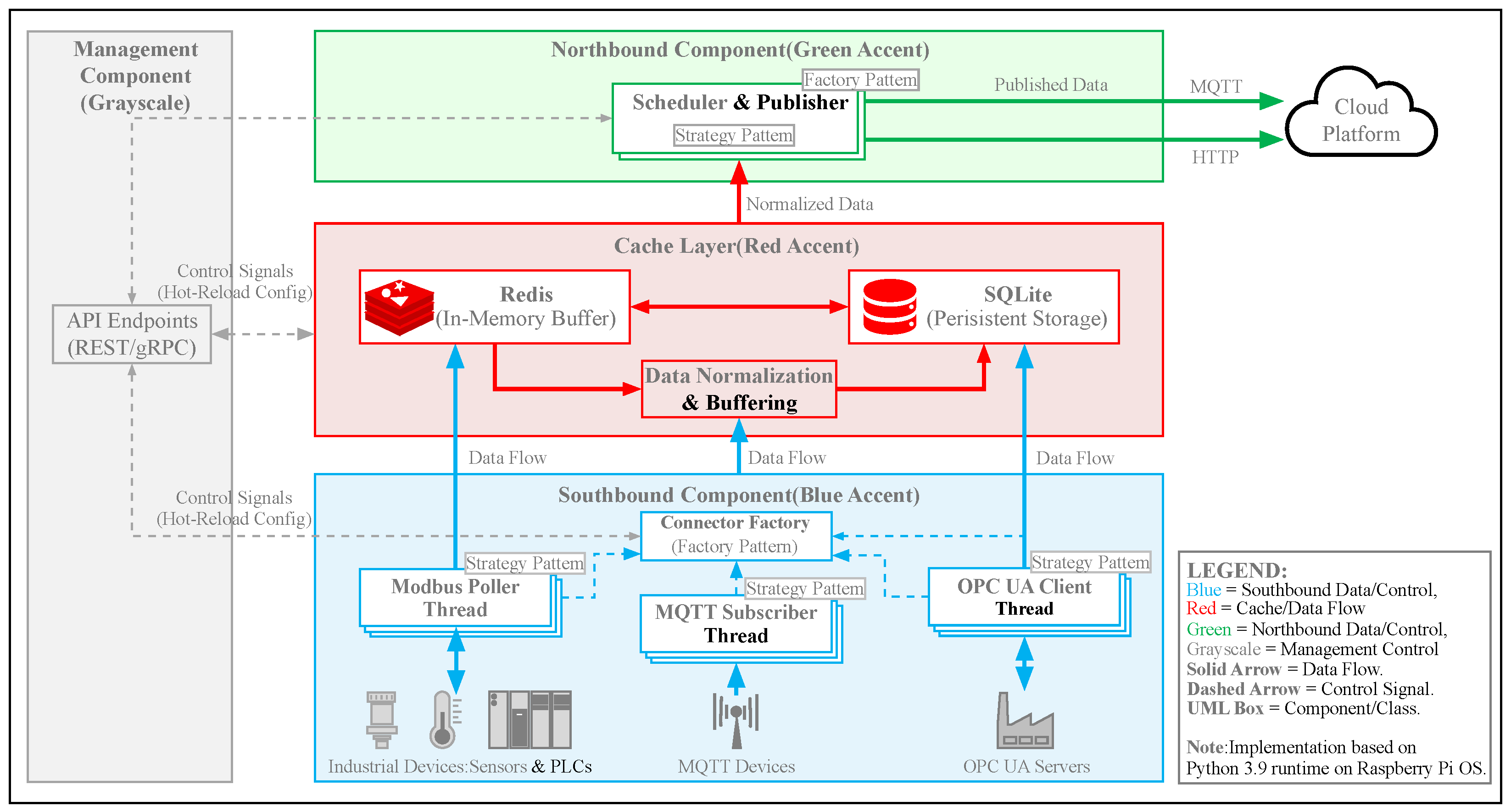

- Modular Architecture Design: We propose a four-component architecture (Management, Southbound, Northbound, Cache) that enhances system scalability and maintainability.

- Instance-Based Connection Management: We introduce a dynamic connection mechanism where each device interface is encapsulated in an independent task thread, preventing single-point failures and ensuring isolation between heterogeneous protocols.

- Decoupled Data Transmission: We describe a robust data handling methodology utilizing an intermediate cache layer to buffer data, ensuring reliability against network volatility.

- Comprehensive Validation: We provide an empirical evaluation of the system’s latency, throughput, and resource utilization under multi-protocol conditions, demonstrating its suitability for industrial applications.

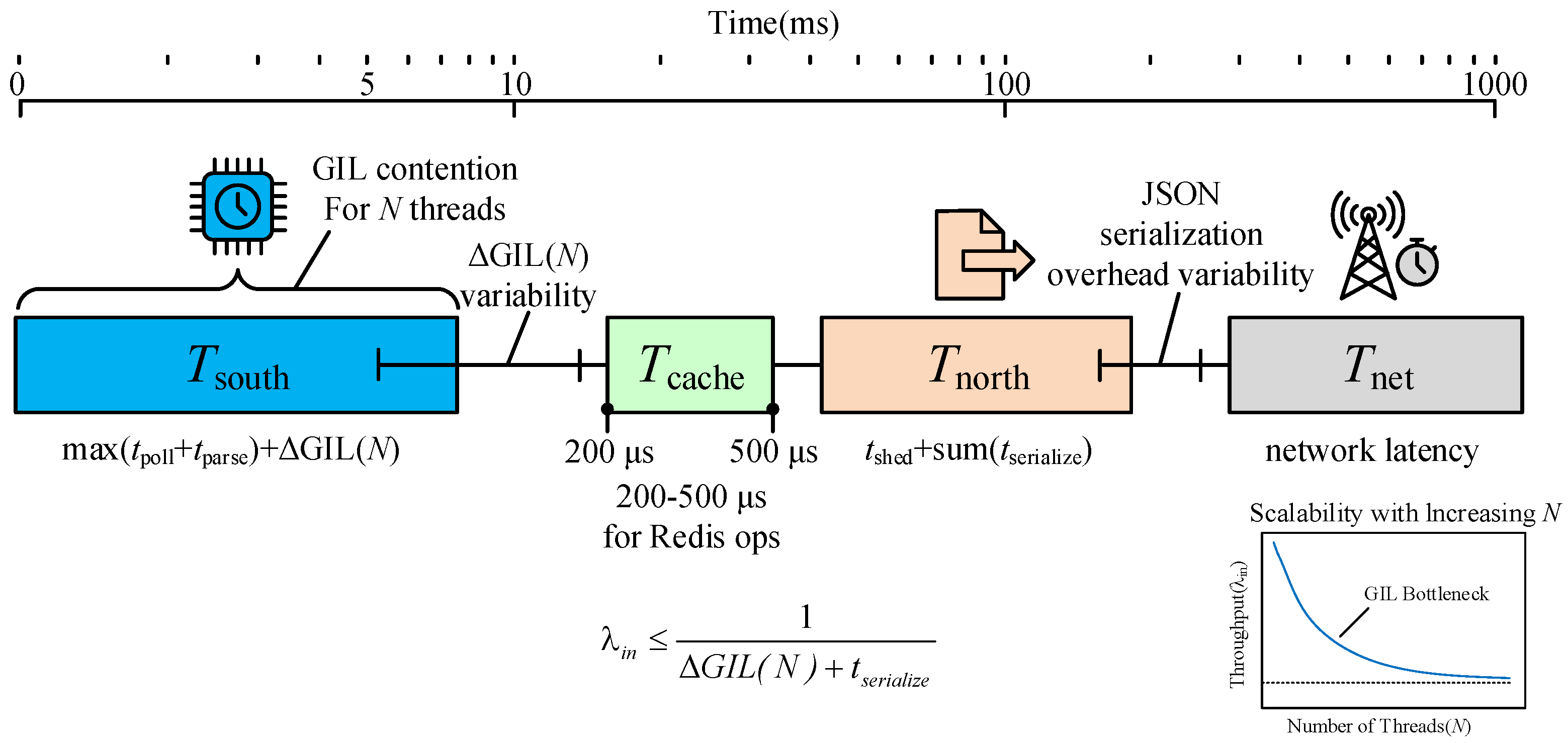

- Theoretical Performance Modeling: We provide a mathematical model for end-to-end system latency, analyzing the constraints of the GIL and serialization processes to identify theoretical throughput bottlenecks.

2. State of the Art

2.1. IoT Gateway Architectures and Interoperability Challenges

2.2. Protocol Integration in Industrial Environments

2.3. Edge Computing and Latency Optimization

3. System Architecture

3.1. Management Component

- Control Service Module: Hosting a RESTful web server (Port 80), this module provides the Human-Machine Interface (HMI) for system administration. It interprets user commands (e.g., device provisioning, protocol configuration) and dispatches them to the core logic via internal IPC mechanisms.

- IoT Service Module: This module encapsulates internal service providers, including a local MQTT broker (Port 1883) and an OPC UA server (Ports 4880/4881). This design allows the gateway to function as a local data aggregator and server, enabling local control loops even when external cloud connectivity is severed.

- Database Module: Utilizing SQLite for configuration persistence, this module stores device profiles, register maps, and network settings. The use of a relational database ensures data integrity and simplifies complex queries for device management.

- OS Management Module: This module encapsulates operating system-level operations, specifically network configuration (e.g., 4G/Ethernet monitoring) and system performance monitoring. It provides real-time metrics such as CPU usage, memory footprint, disk space, and system load, facilitating proactive health monitoring and fault diagnosis.

3.2. Southbound Component

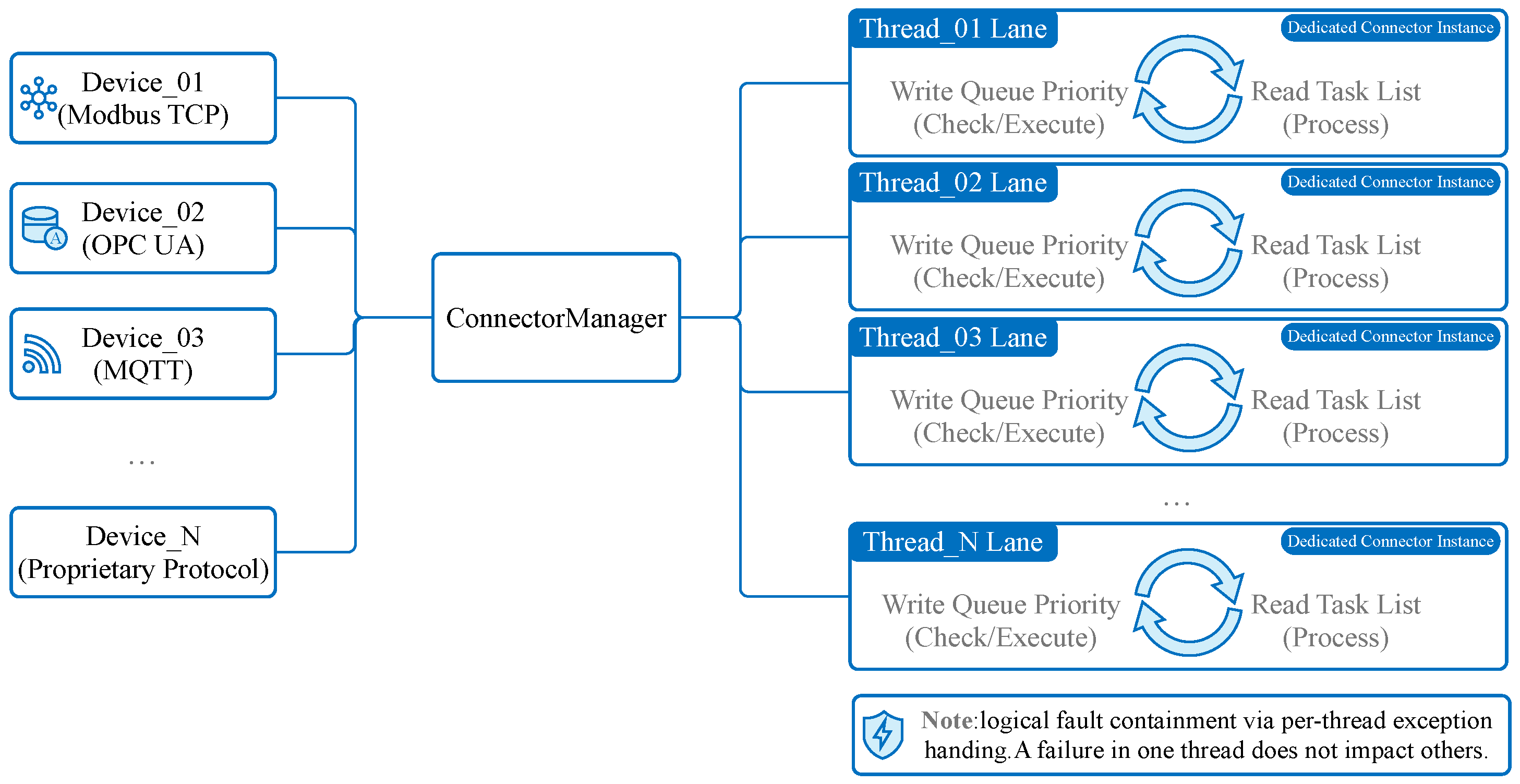

- Connector Manager: This sub-module oversees the lifecycle of all active connectors. It is responsible for instantiation, starting, stopping, and error recovery of connector instances.

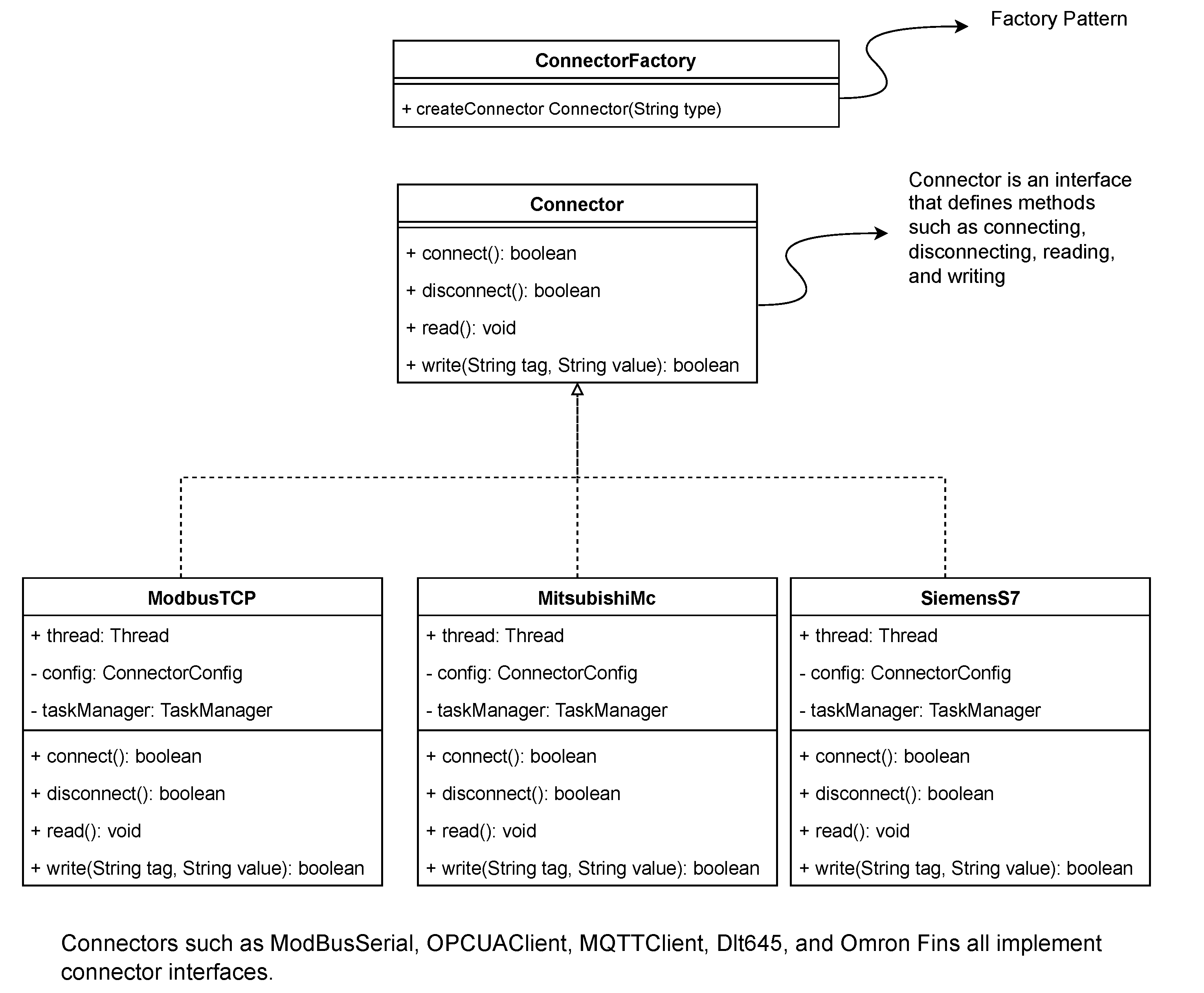

- Connectors (Strategy & Factory Pattern): To support a wide array of protocols (Modbus, Siemens S7, etc.) while adhering to the Open/Closed Principle (OCP), we employ a combination of the Strategy Pattern and Factory Pattern. A unified Connector interface defines standard methods (connect, disconnect, read, write). Specific protocol implementations (e.g., ModbusConnector, OpcUaConnector) implement this interface. At runtime, the Connector Manager uses a Factory to dynamically instantiate the correct strategy based on the configuration. This design allows new protocols to be added by simply creating a new class without modifying existing code. As illustrated in Figure 2.

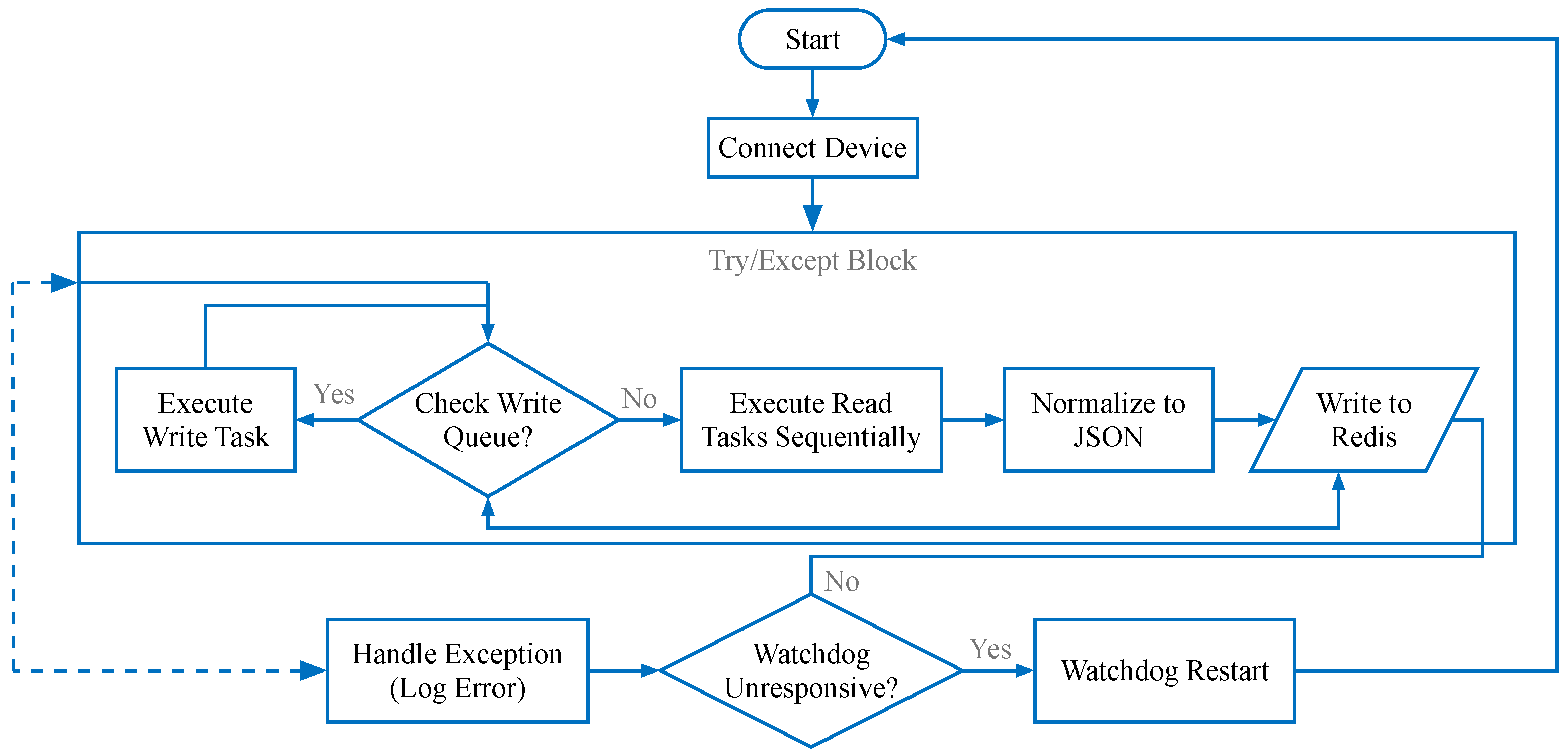

- Task Manager: Each connector instance maintains an internal Task Manager that orchestrates specific data acquisition tasks. As illustrated in Figure 3. A “Task” encapsulates the atomic details of a read operation, such as register address, length, data type, and scaling formulas.

- Instance-Based Isolation: A core innovation of MIGS is its instance-based threading model. For every connected device, a dedicated, isolated thread is spawned.As illustrated in Figure 4. This “one-thread-per-device” architecture ensures that a timeout, blocking operation, or crash in one device driver does not affect the execution of other device tasks.It is important to note that this provides logical fault containment rather than strict OS-level process isolation. While threads share the same memory space and Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), our exception handling wrapper (described in Section 4.4) ensures that a logical error (e.g., protocol parsing failure, device timeout) in one thread is caught and handled locally, preventing it from crashing the main application loop. For catastrophic failures (e.g., segfaults in C-extensions), we recommend external process supervision (e.g., systemd).Note: While MQTT is typically a Northbound protocol, its inclusion in the Southbound component facilitates integration with other smart sensors or sub-gateways that publish data actively. In this context, the Southbound MQTT Connector acts as a subscriber.

3.3. Cache Component

- Decoupling: Southbound tasks write normalized data to the cache immediately upon acquisition. The Northbound Component reads from the cache at its own scheduled intervals.

- Data Normalization: Before storage, raw data from different protocols is normalized into a unified JSON structure (see Section 5.2), ensuring that the Northbound component is agnostic to the source protocol.

- Buffering: The cache provides a temporary buffer, preventing data loss during brief network outages or high-load spikes.

3.4. Northbound Component

- Cloud Platform Manager: This module manages the lifecycle of cloud connections. It supports dynamic configuration of multiple cloud platforms (e.g., AWS IoT, ThingsBoard, Aliyun). As illustrated in Figure 5.

- Scheduling Module: This module implements a configurable polling loop that retrieves fresh data from the Cache Component, As illustrated in Figure 6. It encapsulates the data into standard JSON payloads and transmits them via MQTT or HTTP/S. Additionally, it subscribes to downstream command topics, parsing cloud-originated control instructions and routing them to the appropriate Southbound device instance for execution.

3.5. Security Architecture

- Transport Security: All Northbound communications are encrypted using TLS 1.2/1.3 to prevent eavesdropping and tampering.

- Access Control: The web interface is protected by role-based access control (RBAC) and token-based authentication.

- Isolation: The process isolation between Southbound drivers prevents a compromised or malfunctioning device driver from crashing the entire system kernel.

4. Implementation Details

4.1. Hardware Platform Specification

- SoC: Broadcom BCM2711, Quad-core Cortex-A72 (ARM v8) @ 1.5 GHz.

- Memory: 4 GB LPDDR4 SDRAM.

- Connectivity: Gigabit Ethernet, 2.4/5.0 GHz 802.11ac Wi-Fi, Bluetooth 5.0.

- Storage: 32 GB Class 10 MicroSD for OS and application binaries; external SSD support via USB 3.0 for local data logging.

- Rationalefor Platform Selection: While industrial microcontrollers (e.g., STM32L4 series) running Real-Time Operating Systems (FreeRTOS) offer superior deterministic performance and lower power consumption, they often lack the resources to support high-level dynamic languages and containerization (Docker) central to the MIGS architecture. The Raspberry Pi 4 serves as a representative “High-Level OS” gateway, prioritizing development flexibility, rich Northbound connectivity (SSL/TLS, JSON), and ease of reconfiguration over hard real-time execution. For industrial hardening, the software stack is designed to be portable to industrial-grade Linux gateways (e.g., Siemens IOT2050, Moxa UC-8100).

4.2. Software Stack and Rationale

- Operating System: Raspberry Pi OS (Debian 11 Bullseye, 64-bit) provides a stable, Linux-based foundation with widespread driver support.

- Programming Language: Python 3.9 is utilized for the core application logic. While C++ offers higher raw performance, Python was chosen for its rapid development cycle, rich ecosystem of IoT libraries (e.g., pymodbus, paho-mqtt), and ease of maintenance. Performance-critical sections, such as the underlying protocol drivers, often rely on C-based extensions, mitigating the interpretation overhead.

- Data Store:

- −

- SQLite 3: Used for persistent storage of configuration data. Its serverless, file-based nature makes it ideal for embedded devices where a full-fledged SQL server would be overkill.

- −

- Redis 6.2: Employed for the Cache Component. Its in-memory nature ensures microsecond-level read/write latency, which is crucial for high-frequency data buffering.

- Containerization: Docker is employed to containerize the application services. This ensures consistent deployment environments across different hardware and simplifies the update process via image replacement.

4.3. Protocol Library Integration

- Modbus: The pymodbus library is used for both TCP and RTU communications. We implemented a custom wrapper to handle automatic reconnection with exponential backoff strategies and CRC error checking.

- MQTT: The Eclipse Paho MQTT Python client is integrated, supporting QoS levels 0, 1, and 2, as well as Last Will and Testament (LWT) for connection status monitoring.

- OPC UA: The FreeOpcUa (client) and open62541 (server wrapper) libraries are used. Support includes basic username/password authentication and Basic256Sha256 security policies.

4.4. Error Handling and Resilience

- Watchdog Timer: A software watchdog monitors the status of all critical threads. If a thread becomes unresponsive, it is automatically terminated and restarted.

- Exception Isolation: Each device thread runs within a try-except block to catch unhandled exceptions, logging them to a rotating log file for post-mortem analysis without affecting the main process.

5. Data Transmission Method

5.1. System Initialization Sequence

- Level 0 (Core): The OS Module initializes system resources and mounts the file system.

- Level 1 (Persistence): The Database Module loads and verifies the integrity of the configuration files.

- Level 2 (Services): The Management Component starts the web server and internal MQTT/OPC UA brokers.

- Level 3 (Southbound): The Task Management Module queries the database for active device profiles. For each enabled profile, it instantiates the corresponding protocol object and spawns a dedicated data acquisition thread.

- Level 4 (Northbound): The Northbound Component establishes a secure socket connection to the configured cloud endpoint and begins the scheduling loop.

5.2. Data Normalization Strategy

{

"timestamp": 1678892345,

"device_id": "meter_01",

"protocol": "modbus_tcp",

"data": {

"voltage_a": 220.5,

"current_a": 5.2,

"power_active": 1146.6

},

"status": "ok"

}

5.3. Runtime Control Operations

- Start: The Connector Manager establishes the connection. If successful, it launches the read/write thread.

- Pause: The system signals the thread to terminate gracefully and then closes the physical connection, retaining the configuration in memory.

- Add: The system first validates the user input (e.g., IP address format, register range). If valid, the configuration is written to the database, and the Connector Manager is notified to instantiate the new connector.

- Delete: The system performs a safety check to see if the connector is currently active. If yes, it first triggers the "Pause" logic to stop the thread and release resources. Only after the thread is confirmed stopped is the configuration removed from the database.

- Update: Similar to “Add”, the system validates the new parameters. If valid, it updates the database. If the connector was running, it triggers a “hot reload” (Pause -> Re-instantiate -> Start) to apply changes immediately.

5.4. Theoretical Modeling of System Latency

- represents the time required to acquire data from field devices.

- is the latency introduced by the intermediate Redis storage.

- denotes the processing time for the Northbound component to retrieve and serialize data.

- is the network transmission delay to the cloud.

5.4.1. Parallel Acquisition Latency ()

5.4.2. Serialization and Scheduling Latency ()

5.4.3. Throughput Bottleneck Analysis

6. Performance Evaluation and Discussion

6.1. Experimental Setup

- Gateway: Raspberry Pi 4 (Specifications as in Section 4.1).

- Network: Isolated Gigabit LAN to eliminate external traffic interference.

- Simulated Devices: A high-performance workstation running software simulators for 15 discrete devices (5x Modbus TCP servers, 5x OPC UA servers, 5x MQTT publishers).

- Cloud Endpoint: A local Mosquitto MQTT broker acting as the cloud receiver to measure latency without internet jitter.

- Metrics: End-to-end latency, system throughput (messages/second), CPU/Memory utilization, and packet loss rate.

- Metric Definitions: “Data rate” refers to the number of application-layer JSON payloads successfully transmitted to the Northbound broker per second. Memory usage was measured using the Python memory_profiler library and system-level ps command.

6.2. Latency Analysis

6.3. Throughput and Scalability Analysis

- 0–500 msgs/s: The system maintained 0% packet loss and stable CPU usage (∼40%).

- 1000 msgs/s: CPU utilization rose to ∼78%, but packet loss remained negligible (<0.2%).

- 1500 msgs/s: CPU utilization approached saturation (95.6%), and packet loss increased to 1.8%. This bottleneck is largely attributed to the Python Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) which limits true parallelism on multi-core CPUs, and the serialization overhead of JSON processing.

- Scalability Implication: While the current single-node implementation is sufficient for typical edge deployments (connecting 10–50 sensors), scaling to hundreds of devices would require either horizontal scaling (clustering multiple gateways) or migrating performance-critical components to a compiled language like Go or Rust.

6.4. Resource Utilization Profile

- Memory: Stable consumption between 320–380 MB. The slight fluctuation correlates with the garbage collection cycles of the Python runtime.

- Cache Efficiency: Redis maintained a hit ratio of >99%, confirming that the decoupling strategy effectively isolates the Northbound publisher from Southbound acquisition latency.

6.5. Protocol-Specific Performance

6.6. Comparative Discussion

- vs. Node-RED: While Node-RED offers a lower baseline memory footprint (~150 MB), it operates as a single-threaded Node.js process. A blocking operation or unhandled exception in a single function node can potentially crash the entire runtime or stall other flows. MIGS addresses this by encapsulating each device driver in a protected thread, ensuring that a driver failure does not impact the core management services.

- vs. EdgeX Foundry: EdgeX provides superior process-level isolation through its microservices architecture. However, this comes at the cost of significant resource overhead (>800 MB RAM for a standard deployment) and deployment complexity (requiring orchestration of 10+ containers). MIGS strikes a balance, offering sufficient logical isolation for industrial device polling while maintaining a lightweight footprint suitable for resource-constrained gateways (e.g., Raspberry Pi 3/4) without the operational overhead of a full microservices stack.

6.7. Limitations

- Scalability Constraints under High Concurrency: The current implementation leverages Python’s threading module for instance-based isolation. However, the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) in CPython prevents true parallelism on multi-core processors, effectively serializing CPU-bound operations [33]. While our “one-thread-per-device” model works well for I/O-bound tasks (typical in IoT polling), performance degradation becomes observable when the number of concurrent devices exceeds 50 or when high-frequency data parsing (JSON serialization) saturates the CPU. Future iterations could mitigate this by adopting a multi-process architecture or migrating performance-critical components to a compiled language like Go or Rust.

- Single Point of Failure (SPoF): As a centralized edge node, the gateway itself represents a single point of failure. Although the software architecture ensures that individual device driver crashes do not bring down the system (via process isolation), a hardware failure or OS-level crash would sever connectivity for all downstream devices [1]. The current prototype lacks a native High Availability (HA) mechanism, such as active-passive clustering or Virtual Router Redundancy Protocol (VRRP) support, which are essential for mission-critical industrial scenarios.

- Security Hardware Dependencies: MIGS currently relies on software-based security mechanisms (TLS, Token Auth). It does not integrate with hardware-based security anchors like Trusted Platform Modules (TPM) or Hardware Security Modules (HSM) for secure key storage and boot integrity verification [34]. This leaves the system vulnerable to physical tampering or advanced persistent threats (APTs) where an attacker with root access could extract cryptographic keys.

- Deterministic Latency Limitations: Running on a general-purpose operating system (Raspberry Pi OS/Debian) introduces non-deterministic latency due to OS scheduler preemption and background services [35]. Unlike Real-Time Operating Systems (RTOS), MIGS cannot guarantee hard real-time responses (e.g., <1 ms jitter) required for high-speed motion control applications [31]. Consequently, MIGS is best suited for monitoring, supervisory control, and soft real-time applications rather than closed-loop critical control.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MIGS | Modular IoT Gateway System |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| OPC UA | OPC Unified Architecture |

| OS | Operating System |

| SSL | Secure Sockets Layer |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| GIL | Global Interpreter Lock |

| HMI | Human-Machine Interface |

| IPC | Inter-Process Communication |

| PAL | Protocol Abstraction Layer |

| LWT | Last Will and Testament |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| RBAC | Role-Based Access Control |

| TPM | Trusted Platform Module |

| HSM | Hardware Security Module |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

References

- Ashton, K. That ‘internet of things’ thing. RFID J. 2009, 22, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M. Internet of Things (IoT): A vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2013, 29, 1645–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor Intelligence. IoT Gateway Market—Size, Share 2025–2032; Mordor Intelligence Pvt. Ltd.: Hyderabad, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, R.T. Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures; University of California: Irvine, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mahnke, W.; Leitner, S.H.; Damm, M. OPC Unified Architecture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Zhang, Y. Industrial IoT Gateways: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 8770–8787. [Google Scholar]

- Technavio. Industrial IoT Gateway Market 2025–2029; Technavio: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Khashan, O.A.; Khafajah, N.M. Efficient hybrid centralized and blockchain-based authentication architecture for heterogeneous IoT systems. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 101547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quy, V.K.; Ban, N.T.; Anh, D.V.; Quy, N.M.; Nguyen, D.C. An adaptive gateway selection mechanism for MANET-IoT applications in 5G networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 4567–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouradian, C.; Tahghigh Jahromi, N.; Glitho, R.H. NFV and SDN-based distributed IoT gateway for large-scale disaster management. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 4119–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verba, N.; Chao, K.M.; James, A.; Tawil, A.R. Platform as a service gateway for the Fog of Things. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 33, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noaman, M.; Khan, M.S.; Abrar, M.F.; Ali, S.; Alvi, A.; Saleem, M.A. Challenges in integration of heterogeneous internet of things. Sci. Program. 2022, 2022, 8626882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubidots. Industrial IoT & Edge IoT Gateways: 10+ Best Models for 2025. Available online: https://ubidots.com/blog/top-industrial-iot-gateways (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Busacca, F.; Morello, R.; Cascio, D. A Modular Multi-Interface Gateway for Heterogeneous IoT Networking. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Wang, R.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Qin, W. IOT Gateway: Bridging Wireless Sensor Networks into Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Embedded and Ubiquitous Computing (EUC), Hong Kong, China, 11–13 December 2010; pp. 347–352. [Google Scholar]

- Alagheband, M.R.; Mashatan, A. Advanced digital signatures for preserving privacy and trust management in hierarchical heterogeneous IoT: Taxonomy, capabilities, and objectives. Internet Things 2022, 19, 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, G.; Caliciuri, G.; Fortino, G.; Gravina, R.; Pace, P.; Russo, W.; Savaglio, C. Enabling IoT interoperability through opportunistic smartphone-based mobile gateways. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 174, 102913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, A.; Poveda-Villalón, M.; García-Castro, R. WoT-hive: A semantic interoperability approach for heterogeneous IoT ecosystems based on the Web of Things. Sensors 2020, 20, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, K.; Karmakar, K.K.; Yu, S.; Varadharajan, V.; Pokhrel, S.R.; Xiang, Y. Alleviating heterogeneity in SDN-IoT networks to Maintain QoS and Enhance security. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 5964–5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, A.; Gupta, R. MQTT Version 3.1.1; OASIS: Burlington, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OPC Foundation. OPC UA + MQTT: A Popular Combination for IoT Expansion. Available online: https://opcconnect.opcfoundation.org/2019/09/opc-ua-mqtt-a-popular-combination-for-iot-expansion/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- HiveMQ. Building Industrial IoT Systems in 2024. Available online: https://www.hivemq.com/info/building-industrial-iot-systems-in-2024 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Hameed, R.T.; Mohamad, O.A. Federated learning in IoT: A survey on distributed decision making. Babylon. J. Internet Things 2023, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrovolas, M.; Hajnal, T. Inter-communication between Programmable Logic Controllers using IoT technologies: A Modbus RTU/MQTT Approach. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.05988. [Google Scholar]

- Amazon Web Services. AWS IoT Greengrass. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/greengrass/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Microsoft. Azure IoT Edge. Available online: https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/services/iot-edge/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Eclipse Foundation. Eclipse Kura. Available online: https://www.eclipse.org/kura/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Almutairi, J.; Aldossary, M. Modeling and analyzing offloading strategies of IoT applications over edge computing and joint clouds. Symmetry 2021, 13, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Huang, W.; Liu, T.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y. PPO2: Location Privacy-Oriented Task Offloading to Edge Computing Using Reinforcement Learning for Intelligent Autonomous Transport Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 24, 7599–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Dynamic Resource Management for Mobile Edge Computing in Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 4925–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriulo, F.; Fiore, M.; Mongiello, M.; Traversa, E.; Zizzo, V. Edge Computing and Cloud Computing for Internet of Things: A Review. Informatics 2024, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, R.; Boukerche, A. Modeling and Performance Evaluation of Collaborative IoT Cross-Camera Video Analytics. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Rome, Italy, 28 May–1 June 2023; pp. 1804–1809. [Google Scholar]

- Advantech. Industrial IoT Gateway Solutions. Available online: https://www.advantech.com/th-th/products/industrial-iot-edge-gateway/sub_9a0cc561-8fc2-4e22-969c-9df90a3952b5 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Zhao, Z.; Zhao, S.; Lv, F.; Si, S.; Zhu, H.; Sun, L. RIETD: A Reputation Incentive Scheme Facilitates Personalized Edge Tampering Detection. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 14771–14788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawakuli, A.; Havers, B.; Gulisano, V.; Kaiser, D.; Engel, T. Survey: Time-series data preprocessing: A survey and an empirical analysis. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 13, 674–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisco. Cisco IoT Gateways. Available online: https://blogs.cisco.com/tag/cisco-iot-gateway (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Siemens. Simatic IoT2050. Available online: https://new.siemens.com/global/en/products/automation/pc-based/iot-gateways/simatic-iot2050.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Dell Technologies. Dell Edge Gateway. Available online: https://www.dell.com/en-us/work/shop/gateways-embedded-computing/sc/gateways-embedded-computing (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Intel. Intel IoT Gateway Technology. Available online: https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/internet-of-things/gateway-solutions.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Huawei. AR Series IoT Gateways. Available online: https://e.huawei.com/en/products/enterprise-networking/routers/ar-industrial (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Moxa. IIoT Gateways. Available online: https://www.moxa.com/en/products/industrial-computing/iiot-gateways (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Eurotech. ReliaGATE. Available online: https://www.eurotech.com/en/products/iot-gateways (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- ADLINK. IoT Gateways. Available online: https://www.adlinktech.com/en/IoT_Gateway (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Digi International. Digi IX Series. Available online: https://www.digi.com/products/networking/cellular-routers/industrial (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Sierra Wireless. AirLink Routers and Gateways. Available online: https://www.sierrawireless.com/products-and-solutions/routers-gateways/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- MultiTech. MultiConnect Conduit. Available online: https://www.multitech.com/brands/multiconnect-conduit (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Lantronix. IoT Gateways. Available online: https://www.lantronix.com/products-class/iot-gateways/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- HMS Networks. Ewon Flexy. Available online: https://www.ewon.biz/products/ewon-flexy (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Red Lion. Industrial Gateways. Available online: https://www.redlion.net/products/industrial-networking/gateways (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Pepperl+Fuchs. IoT Gateways. Available online: https://www.pepperl-fuchs.com/global/en/classid_186.htm (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Phoenix Contact. IoT Gateway. Available online: https://www.phoenixcontact.com/en-us/product-list-webcode-3836 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- WAGO. IoT Box. Available online: https://www.wago.com/global/interface-electronic/iot-box (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Beckhoff. IoT Bus Coupler. Available online: https://www.beckhoff.com/en-en/products/i-o/ethercat-terminals/ekxxxx-bus-coupler/ek9160.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- B&R Industrial Automation. Edge Controller. Available online: https://www.br-automation.com/en/products/industrial-pc/edge-controller/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Rockwell Automation. Allen-Bradley Edge Gateway. Available online: https://www.rockwellautomation.com/en-us/products/hardware/allen-bradley/industrial-computers-monitors/edge-gateway.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Emerson. RX3i Edge Controller. Available online: https://www.emerson.com/en-us/catalog/emerson-rx3i-cpl410 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Yokogawa. IIoT Gateway. Available online: https://www.yokogawa.com/solutions/solutions/iiot-plant-asset-management/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Honeywell. Honeywell Forge. Available online: https://www.honeywell.com/us/en/honeywell-forge (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- General Electric. Predix Edge. Available online: https://www.ge.com/digital/iiot-platform (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- IBM. IBM Watson IoT Platform. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/internet-of-things (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Google Cloud. Cloud IoT Core. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/iot-core (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Oracle. Oracle IoT Cloud. Available online: https://www.oracle.com/internet-of-things/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- SAP. SAP Internet of Things. Available online: https://www.ibsolution.com/en/smart-enterprise/sap-iot-internet-of-things (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- PTC. ThingWorx. Available online: https://www.ptc.com/en/products/thingworx (accessed on 1 December 2025).

| Module | Key Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Control Service | Provides Web API (Port 80) for user management and system configuration. |

| Connector Manager | Manages lifecycle (Init, Start, Stop) of all protocol connectors using Factory pattern. |

| Task Manager | Orchestrates atomic read/write tasks for each connection instance. |

| Cloud Platform Manager | Handles authentication and connection maintenance for external clouds (e.g., ThingsBoard). |

| OS Management | Monitors system health (CPU, RAM, Network) and handles network interface configuration. |

| Concurrent Devices | Min Latency | Max Latency | Avg. Latency | 95th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 devices | 23 | 45 | 32 | 41 |

| 10 devices | 28 | 78 | 45 | 69 |

| 15 devices | 35 | 125 | 67 | 108 |

| Data Rate (msgs/s) | CPU Utilization (%) | Memory Usage (MB) | Packet Loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 18.5 | 245 | 0.0 |

| 500 | 42.3 | 318 | 0.0 |

| 1000 | 78.9 | 425 | 0.2 |

| 1500 | 95.6 | 587 | 1.8 |

| Protocol | Connection Time (ms) | Data Point Transmission (ms) | Memory per Instance (KB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modbus TCP | 12.3 | 8.7 | 156 |

| OPC UA | 245.8 | 15.2 | 892 |

| MQTT | 34.6 | 5.3 | 234 |

| Feature | MIGS (Proposed) | Node-RED (v3.1) | EdgeX Foundry (v3.1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Modular Monolith (Python Threads) | Event-driven Flow (Node.js) | Microservices (Go) |

| Min. Memory Footprint | ~350 MB (Measured) | ~150 MB (Base) | >800 MB (Standard) |

| Fault Isolation | Logical (Thread Exception Handling) | None (Single Process Runtime) | High (Container/Process Level) |

| Configuration Update | Hot-reload (Zero Downtime) | Full Flow Redeploy (Brief Pause) | Dynamic via Consul Registry |

| Deployment Complexity | Low (Single Container/Script) | Low (Single Container/npm) | High (Docker Compose/K8s) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, Y. MIGS: A Modular Edge Gateway with Instance-Based Isolation for Heterogeneous Industrial IoT Interoperability. Sensors 2026, 26, 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010314

Ai Y, Zhu Y, Jiang Y, Deng Y. MIGS: A Modular Edge Gateway with Instance-Based Isolation for Heterogeneous Industrial IoT Interoperability. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):314. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010314

Chicago/Turabian StyleAi, Yan, Yuesheng Zhu, Yao Jiang, and Yuanzhao Deng. 2026. "MIGS: A Modular Edge Gateway with Instance-Based Isolation for Heterogeneous Industrial IoT Interoperability" Sensors 26, no. 1: 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010314

APA StyleAi, Y., Zhu, Y., Jiang, Y., & Deng, Y. (2026). MIGS: A Modular Edge Gateway with Instance-Based Isolation for Heterogeneous Industrial IoT Interoperability. Sensors, 26(1), 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010314