Study of Hydraulic Disturbance Transient Processes in Pumped-Storage Power Stations Considering Electro-Mechanical Coupling

Abstract

1. Introduction

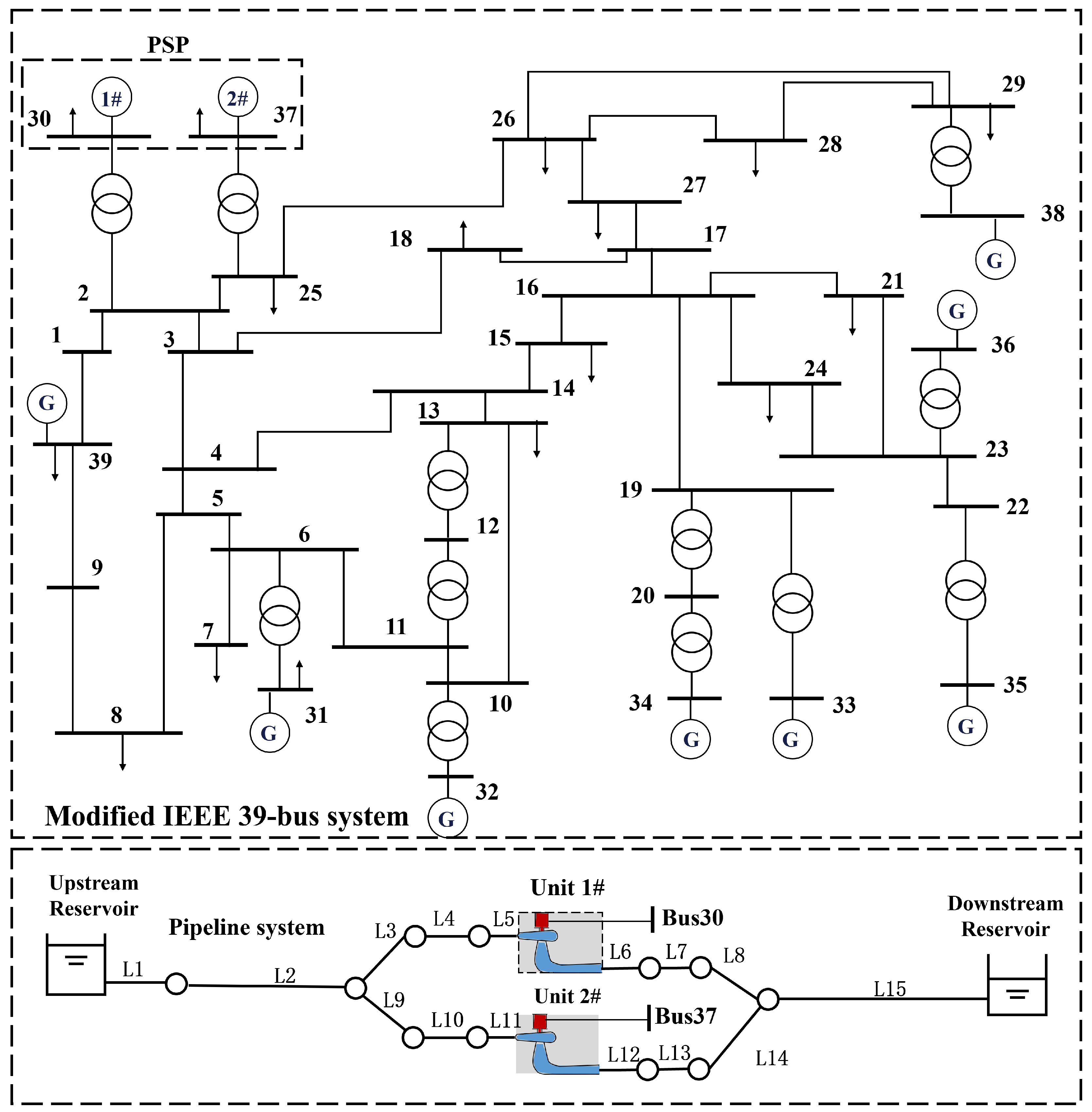

2. Mathematical Modeling

2.1. Model of Hydraulic Conduit System

2.2. Model of Pumped-Storage Unit and Generator

2.3. Model of the Power System

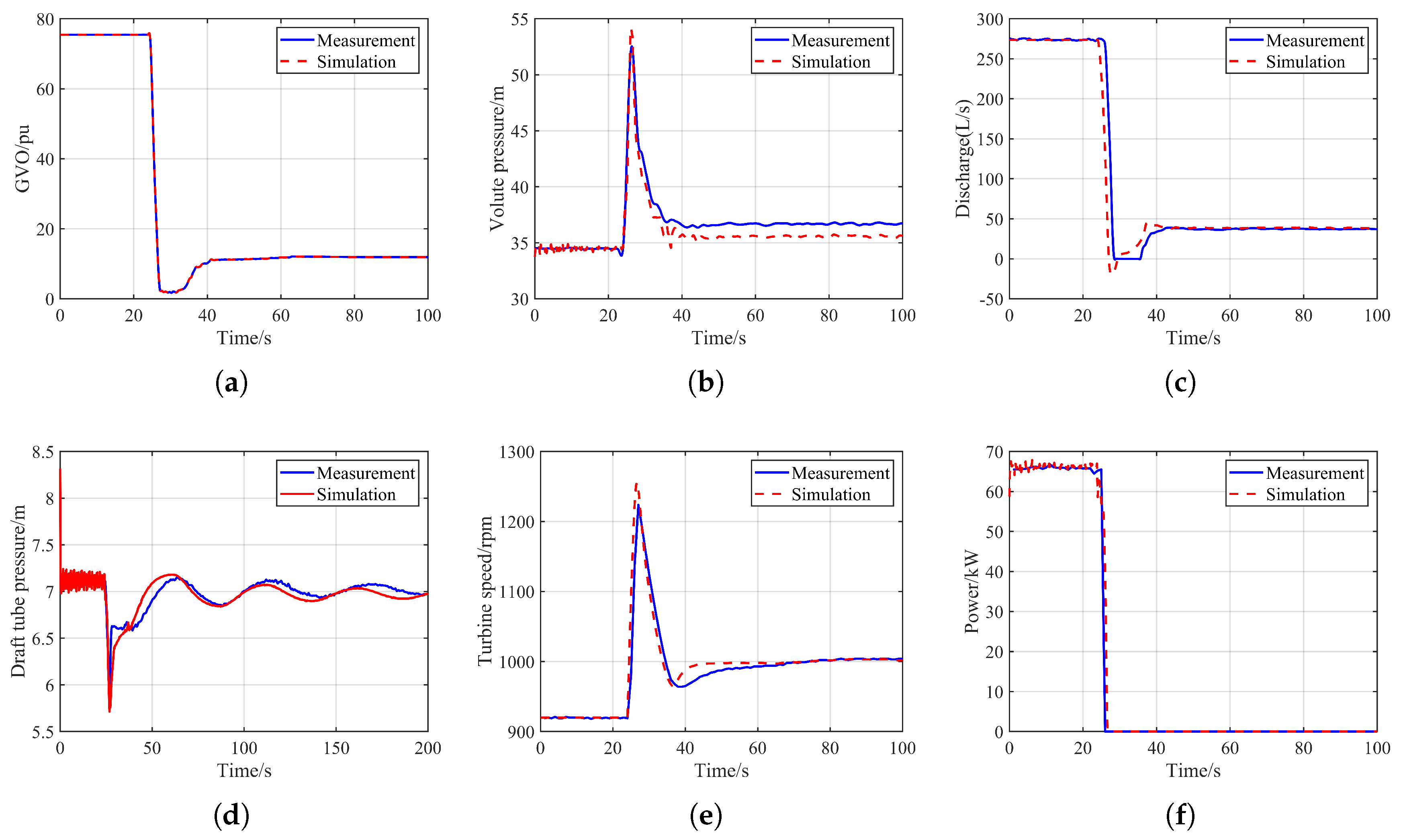

3. Experimental Testing and Model Validation

3.1. Experimental Platform of Pumped Storage System

3.2. Model Verification and Validation

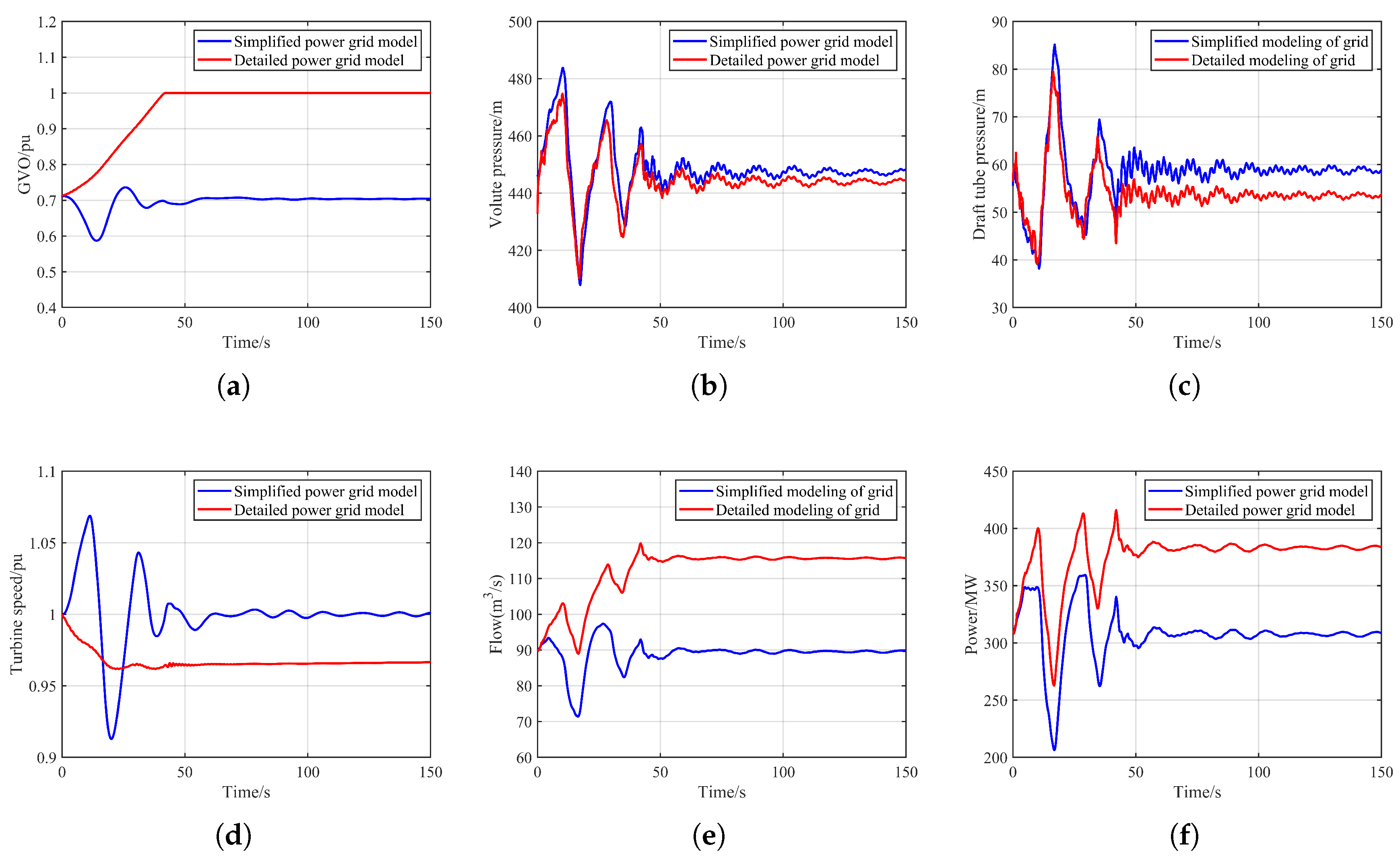

4. Analysis of Hydraulic Disturbance Transient Processes

4.1. Comparison of the Electrically Coupled Model and the Traditional Model

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Hydro-Mechanical-Electrical System Parameters

4.2.1. Influence of Power System Inertia

4.2.2. Influence of GVO Closing Time

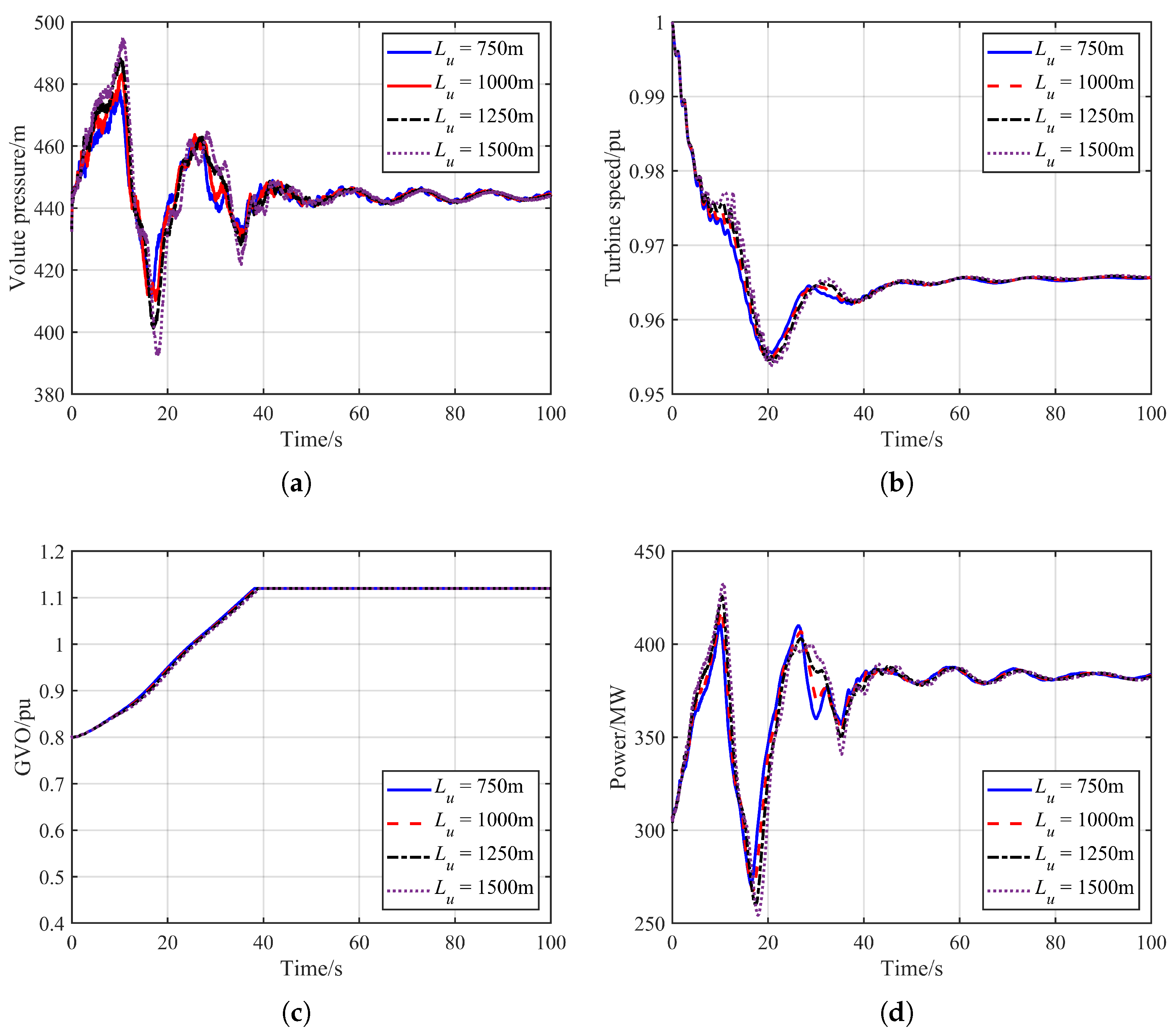

4.2.3. Influence of Tunnel Length

5. Discussion

- (1)

- Additional influencing factors

- (2)

- Mechanism Analysis and Contribution Assessment

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Detailed grid modeling has a significant impact on the hydraulic disturbance transient process of pumped-storage power stations. When grid dynamics are considered, load rejection causes a frequency drop, and the operating unit must compensate for the resulting power deficit. This leads to a decrease in its rotational speed and an increase in GVO, which helps mitigate water-hammer pressure to some extent. The unit rotational speed and guide vane opening exhibit response trends that differ from those predicted by simplified grid models. This phenomenon is associated with grid-unit interaction mechanisms and is not limited to a specific water conveyance layout.

- (2)

- Hydraulic–mechanical parameters, such as the length of the headrace tunnel and the guide vane closing rate, have significant impacts on the dynamic characteristics of hydraulic disturbance. These parameters directly affect the magnitude of water-hammer pressure and the peak power output. Meanwhile, the dynamic evolution of guide vane opening is strongly influenced by grid-frequency regulation and control strategies, indicating that the observed dynamic behaviors are closely related to the adopted governor control mode.

- (3)

- Variations in grid inertia have relatively minor effects on the hydraulic disturbance process within the range investigated in this study. Within the scope of this study, differences in inertia lead to only small variations in unit rotational speed, pressure, and power responses. The dynamic behavior of the operating unit is still dominated by the characteristics of the hydraulic system.The influence of grid inertia may become more pronounced under other grid conditions or control strategies and warrants further investigation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khalili, S.; Lopez, G.; Breyer, C. Role and trends of flexibility options in 100% renewable energy system analyses towards the Power-to-X Economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 212, 115383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, Y.F.; El-Khozondar, H.J.; Fakher, M.A. The role of hybrid renewable energy systems in covering power shortages in public electricity grid: An economic, environmental and technical optimization analysis. J. Energy Storage 2025, 108, 115224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enasel, E.; Dumitrascu, G. Storage solutions for renewable energy: A review. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CREEI. Annual Report on China’s Renewable Energy Development 2024; CREEI: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, X.; Huang, H.; Zheng, B.; Li, D.; Zong, Y. Nonlinear modeling and stability analysis of asymmetric hydro-turbine governing system. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 120, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.D.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Hydraulic Disturbance in Multiturbine Hydraulically Coupled Systems of Hydropower Plants Caused by Load Variation. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2019, 145, 04018078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleznev, V.; Liseikin, A.; Bryksin, A.; Gromyko, P. What Caused the Accident at the Sayano-Shushenskaya Hydroelectric Power Plant (SSHPP): A Seismologist’s Point of View. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2014, 85, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.P.; Zhao, Z.G.; Yang, J.B.; Yan, S.K.; Yang, J.D.; Yin, X.X. Hydraulic-mechanical-electrical coupled model framework of variable-speed pumped storage system: Measurement verification and accuracy analysis. J. Energy Storage 2024, 89, 111714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Jin, J.; Xu, B.; Chen, D.; Egusquiza, M.; Kim, J.; Egusquiza, E.; Jafar, N.; Xu, L.; Kuang, Y. Physical model test and parametric optimization of a hydroelectric generating system with a coaxial shaft surge tank. Renew. Energy 2022, 200, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulu, B.G.; Jonsson, P.P.; Cervantes, M.J. Experimental investigation of a Kaplan draft tube—Part I: Best efficiency point. Appl. Energy 2012, 93, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilong, C.; Wencheng, G. Energy coupling and surge wave superposition of upstream series double surge tanks of pumped storage power station. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, J.; Lai, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, M. Nonlinear stability and dynamic characteristics of grid-connected hydropower station with surge tank of a long lateral pipe. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 136, 107654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wu, F. Hydraulic-mechanical coupling vibration performance of pumped storage power station with two turbine units sharing one tunnel. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53, 105082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Li, C.; Guo, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y. Stability and dynamic characteristics of the nonlinear coupling system of hydropower station and power grid. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2019, 79, 104919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Tang, Y.; Mu, C. A multiple model framework based on time series clustering for shale gas well pressure prediction. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 95, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Z.; Tan, X. Influence of water diversion system topologies and operation scenarios on the damping characteristics of hydropower units under ultra-low frequency oscillations. Energy 2022, 239, 122679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, J.; Lai, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, J. A transient analysis framework for hydropower generating systems under parameter uncertainty by integrating physics-based and data-driven models. Energy 2024, 297, 131141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Chen, L.; Dlakavu, N.; Shen, Z. Basic modeling and simulation tool for analysis of hydraulic transients in hydroelectric power plants. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2008, 23, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Guo, W.; Wang, C. Power-speed coupling response characteristics of variable speed pumped storage unit under pumping mode. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 166, 110544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Xu, Y.; Guo, P.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W. Multi-scale oscillation characteristics and stability analysis of pumped-storage unit under primary frequency regulation condition with low water head grid-connected. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 1102–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Feng, C.; Shan, Y.; Sun, N.; Xue, X.; Shi, L. A universal stability quantification method for grid-connected hydropower plant considering FOPI controller and complex nonlinear characteristics based on improved GWO. Renew. Energy 2023, 211, 874–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, S.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhou, J. Interface Displacement and Dynamic Phasor Mapping Equivalence Based Hybrid Simulation for HVAC/DC Power Grids. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 1932–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.H.; Castro, L.M. Novel VSC-Based STATCOM Model Based on Dynamic Phasors for Unbalanced Distribution Networks. IEEE Open Access J. Power Energy 2024, 11, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, L.; Ma, Y.; Xiang, P.; Jiang, S.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M. Transient Stability Simulation Analysis of Multi Node Power Network with Variable Speed Pumped Storage Units. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 18, 2811–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Bao, Z.; Mao, Z.; Rashad, E.M. Modeling and Transient Response Analysis of Doubly-Fed Variable Speed Pumped Storage Unit in Pumping Mode. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 9935–9947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezghi, A.; Riasi, A. The interaction effect of hydraulic transient conditions of two parallel pump-turbine units in a pumped-storage power plant with considering “S-shaped” instability region: Numerical simulation. Renew. Energy 2018, 118, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Qu, F. Stability control of dynamic system of hydropower station with two turbine units sharing a super long headrace tunnel. J. Frankl. Inst. 2021, 358, 8506–8533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Guo, W.; Qu, F. Hydraulic disturbance characteristics and power control of pumped storage power plant with fixed and variable speed units under generating mode. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.L.; Guo, W.C. Hydraulic superposition of hybrid pumped storage system considering successive load rejections under generation and hydraulic short circuit. Renew. Energy 2025, 240, 122206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.L.; Guo, W.C.; Zhang, T.Y. Superposition control of extreme water levels in surge tanks of pumped storage power station with two turbines under combined operating conditions. J. Energy Storage 2022, 56, 105894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, X.; Yang, J. Does the upstream gate control scheme threaten the safety of extra-long pressurized water diversion tunnel: Gas-liquid evolution characteristics of the filling process. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 094130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.P.; Peng, T.; Yang, J.B.; Zhao, Z.G.; Yang, J.D. Transient Process of Pumped Storage System Coupling Gas-Liquid Interface: Novel Mathematical Model and Experimental Verification. Water 2021, 13, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Gu, N.; Egusquiza, M.; Lei, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, D.; Xu, B.; Egusquiza, E. Parameter optimization decision framework for transient process of a pumped storage hydropower system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 286, 117064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Wang, H.; Xu, R.; Lu, X.; Zhu, Z. Multi-time scale model reduction strategy of variable-speed pumped storage unit grid-connected system for small-signal oscillation stability analysis. Renew. Energy 2023, 211, 985–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Pal, B.C. IEEE PES Task Force on Benchmark Systems for Stability Controls: Report on the 68-Bus, 16-Machine, 5-Area System; IEEE Power & Energy Society: Piscataway, MJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, W.; Ding, J. Parameter uncertainty and sensitivity of pumped storage system with surge tank under grid-connected operating condition. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ye, H.; Gao, S.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L. Modeling and simulation of large power system with inclusion of bipolar MTDC grid. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 116, 105565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, H.R.; Aneros, K.; Edris, A.A.; Torseng, S. Advanced simulation techniques for the analysis of power system dynamics. IEEE Comput. Appl. Power 1990, 3, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.M.; Mirheydar, M. A low-order system frequency response model. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1990, 5, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, G.; Wagle, R.; Dicorato, M.; Forte, G.; Gonzalez-Longatt, F.; Rueda, J.L. A Modified Version of the IEEE 39-bus Test System for the Day-Ahead Market. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PES Conference on Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Middle East (ISGT Middle East), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 12–15 March 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

| Grid Inertia | Maximum Volute Pressure/m | Minimum Draft-Tube Pressure/m | Minimum Unit Speed/pu | Maximum Unit Output/MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| = 30 | 475.16 | 38.83 | 0.949 | 423.35 |

| = 60 | 475.64 | 38.82 | 0.951 | 422.15 |

| = 120 | 476.16 | 38.89 | 0.954 | 419.81 |

| = 240 | 476.62 | 38.91 | 0.961 | 415.91 |

| Grid Inertia | Maximum Volute Pressure/m | Minimum Draft-Tube Pressure/m | Minimum Unit Speed/pu | Maximum Unit Output/MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| = 25 s | 480.43 | 33.83 | 0.957 | 418.30 |

| = 35 s | 477.69 | 36.97 | 0.955 | 410.31 |

| = 45 s | 476.15 | 38.89 | 0.954 | 419.81 |

| = 55 s | 474.32 | 39.64 | 0.954 | 417.11 |

| Grid Inertia | Maximum Volute Pressure/m | Minimum Draft-Tube Pressure/m | Minimum Unit Speed/pu | Maximum Unit Output/MW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| = 750 m | 477.85 | 36.91 | 0.955 | 410.52 |

| = 1000 m | 483.50 | 37.72 | 0.954 | 417.59 |

| = 1250 m | 488.15 | 38.14 | 0.954 | 425.69 |

| = 1500 m | 495.23 | 39.47 | 0.953 | 432.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, X.; Yang, J. Study of Hydraulic Disturbance Transient Processes in Pumped-Storage Power Stations Considering Electro-Mechanical Coupling. Sensors 2026, 26, 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010311

Liu C, Zhao Z, Yin X, Yang J. Study of Hydraulic Disturbance Transient Processes in Pumped-Storage Power Stations Considering Electro-Mechanical Coupling. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):311. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010311

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Chengpeng, Zhigao Zhao, Xiuxing Yin, and Jiandong Yang. 2026. "Study of Hydraulic Disturbance Transient Processes in Pumped-Storage Power Stations Considering Electro-Mechanical Coupling" Sensors 26, no. 1: 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010311

APA StyleLiu, C., Zhao, Z., Yin, X., & Yang, J. (2026). Study of Hydraulic Disturbance Transient Processes in Pumped-Storage Power Stations Considering Electro-Mechanical Coupling. Sensors, 26(1), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010311