Semi-Supervised Object Detection: A Survey on Progress from CNN to Transformer

Abstract

1. Introduction

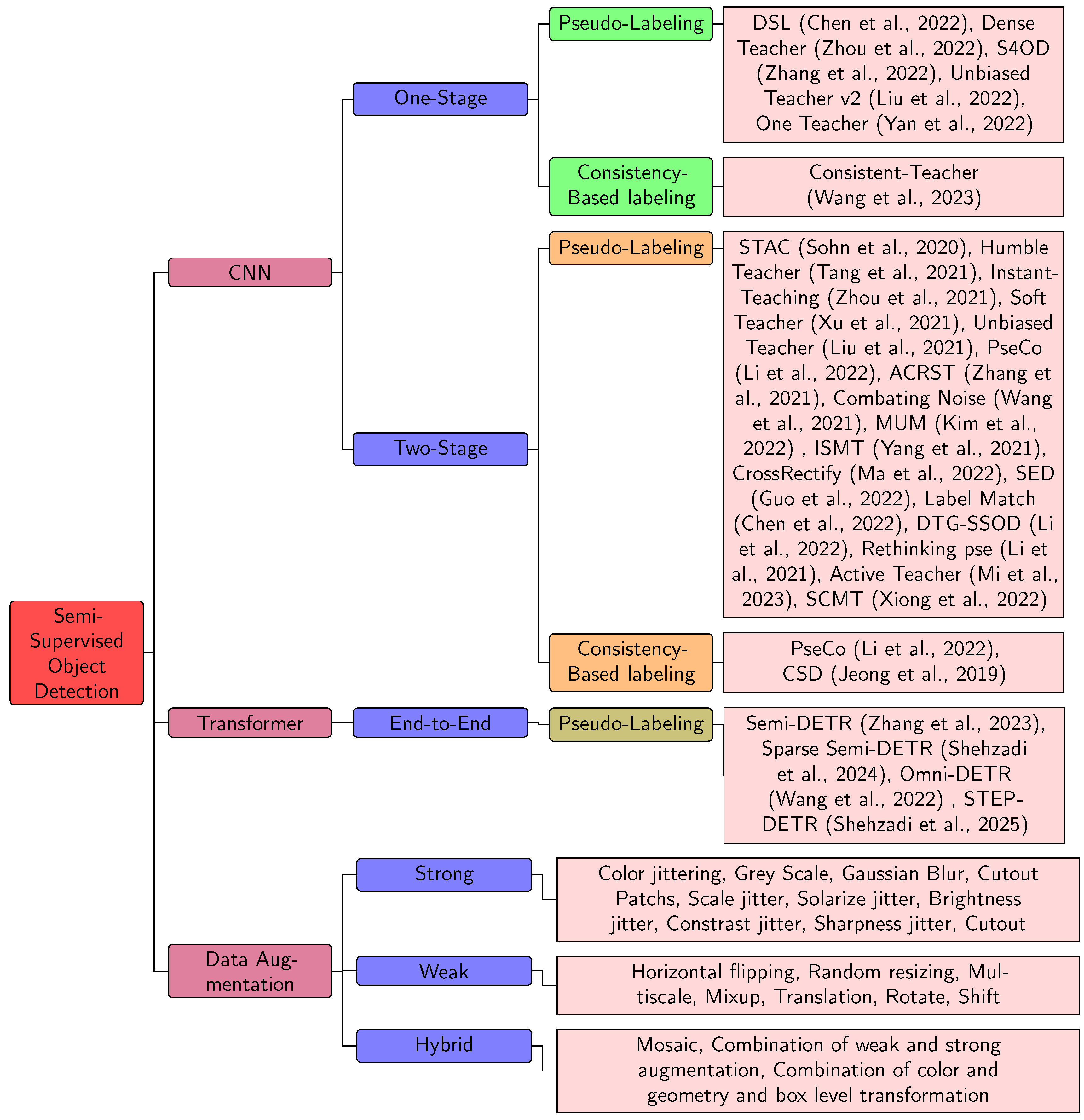

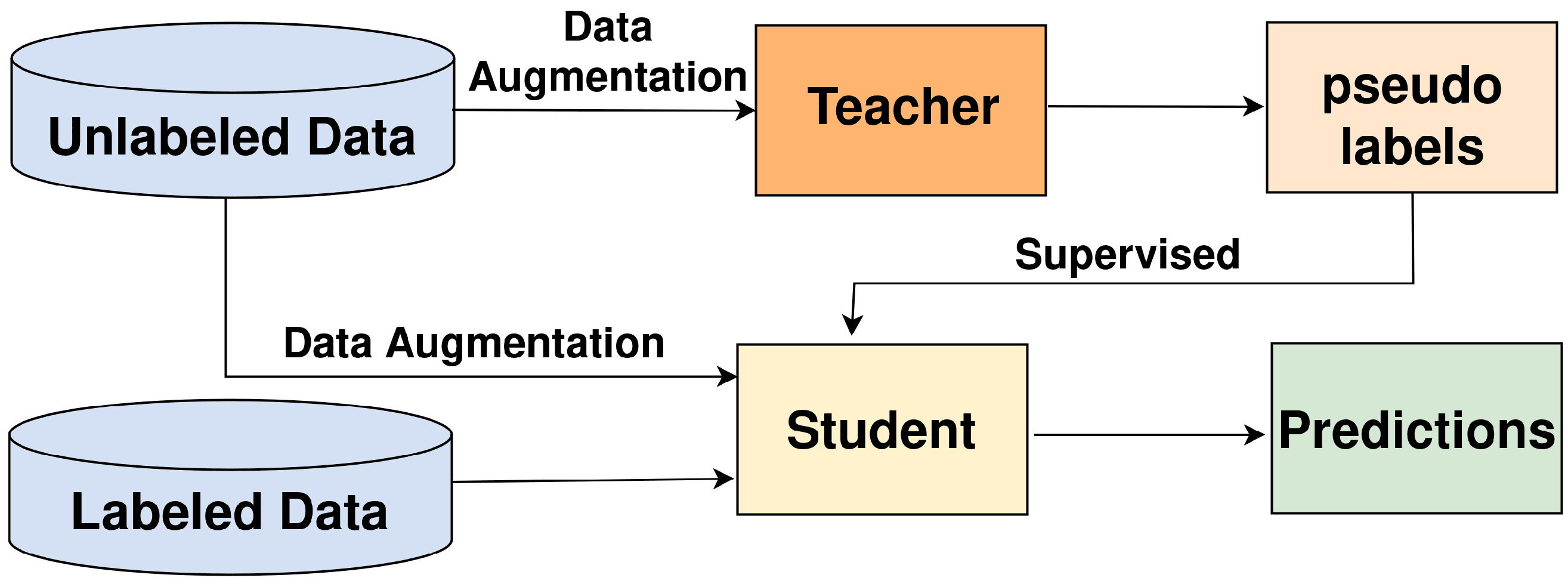

2. Semi Supervised Strategies

2.1. One Stage

2.1.1. One Teacher

2.1.2. DSL

2.1.3. Dense Teacher

2.1.4. Unbiased Teacher v2

2.1.5. S4OD

2.1.6. Consistent-Teacher

2.2. Two Stage

2.2.1. Rethinking Pse

2.2.2. CSD

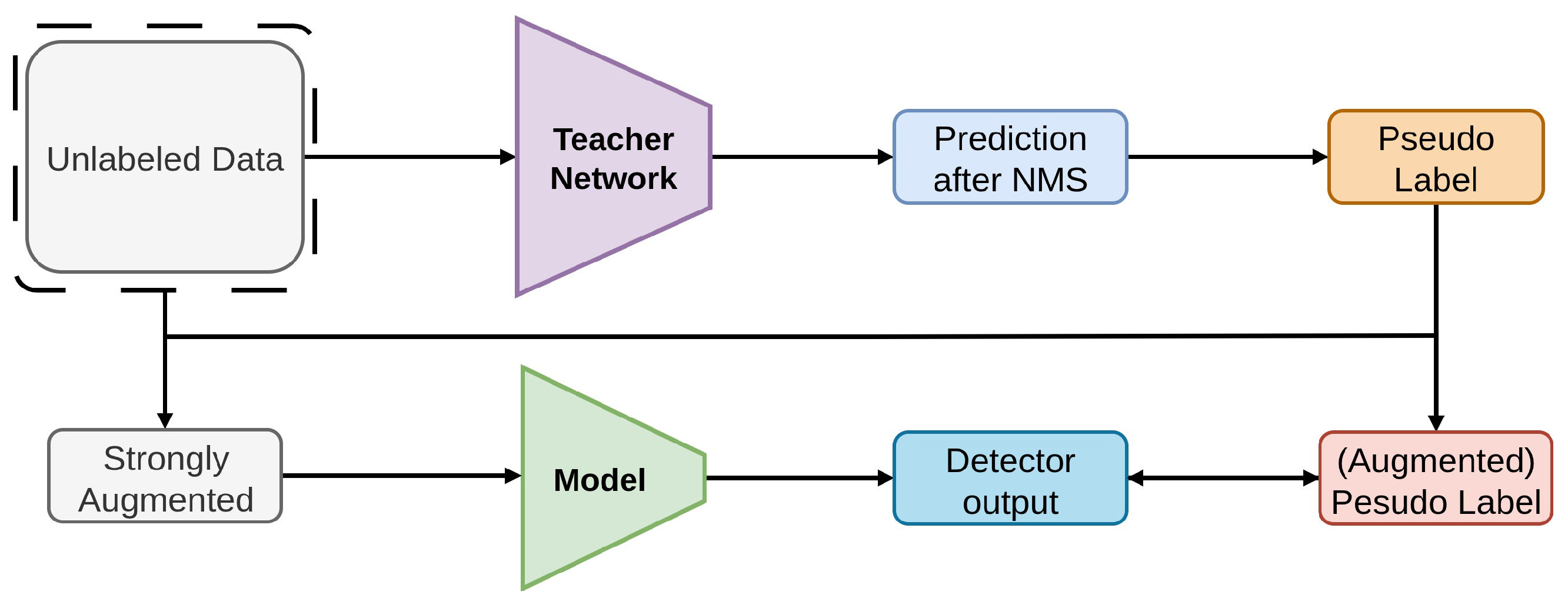

2.2.3. STAC

2.2.4. Humble Teacher

2.2.5. Combating Noise

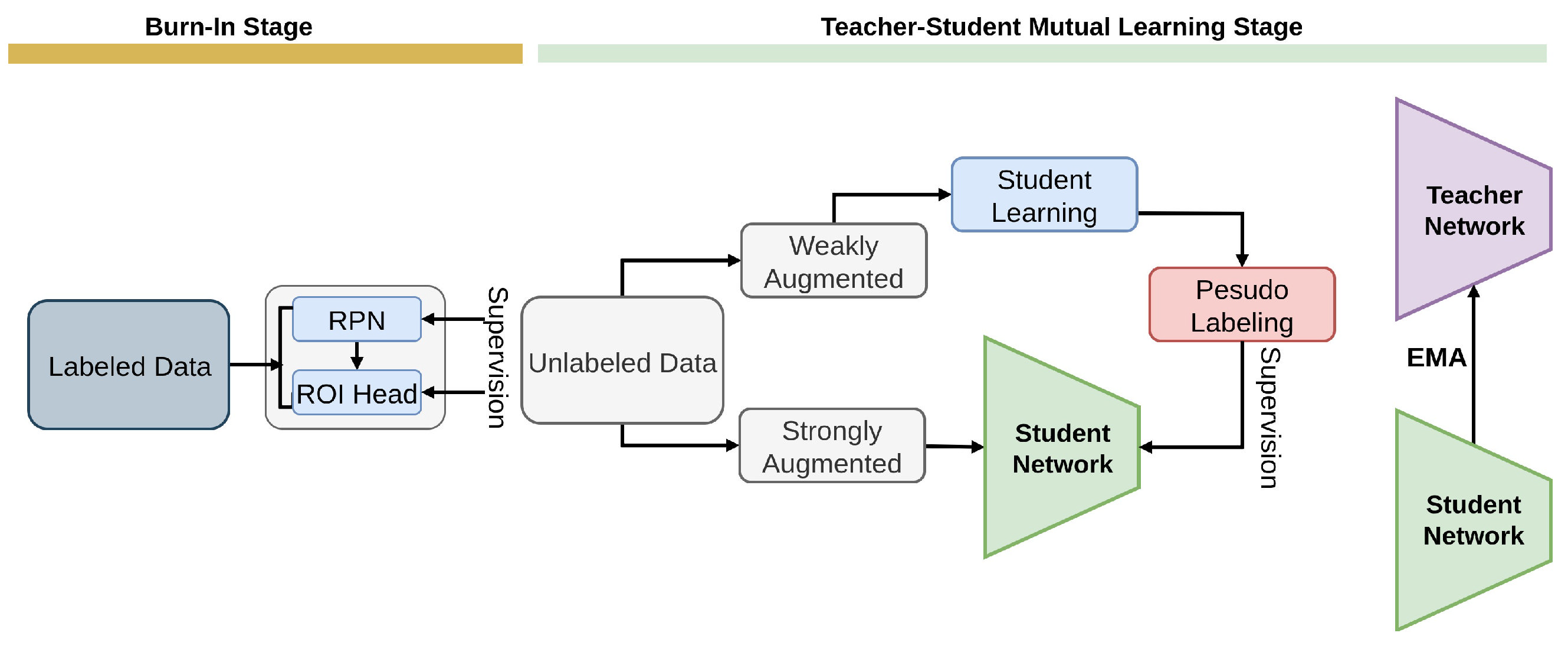

2.2.6. ISMT

2.2.7. Instant-Teaching

2.2.8. Soft Teacher

2.2.9. Unbiased Teacher

2.2.10. DTG-SSOD

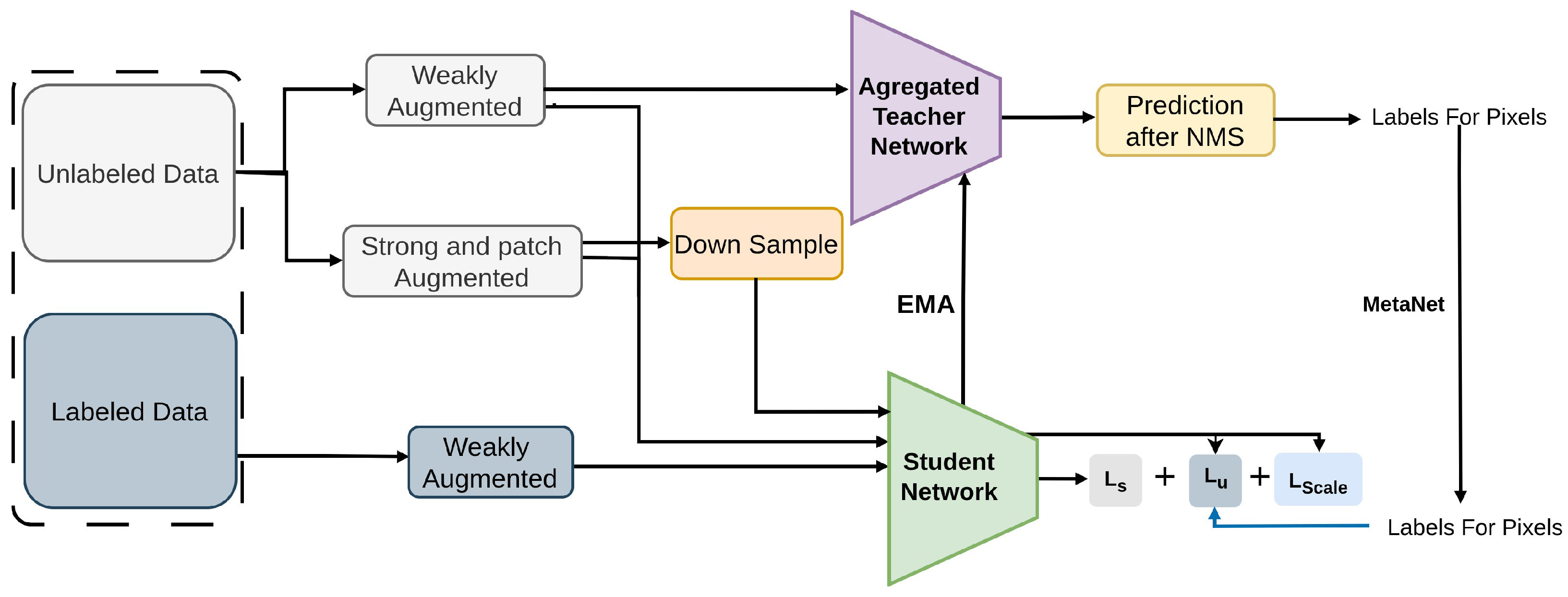

2.2.11. MUM

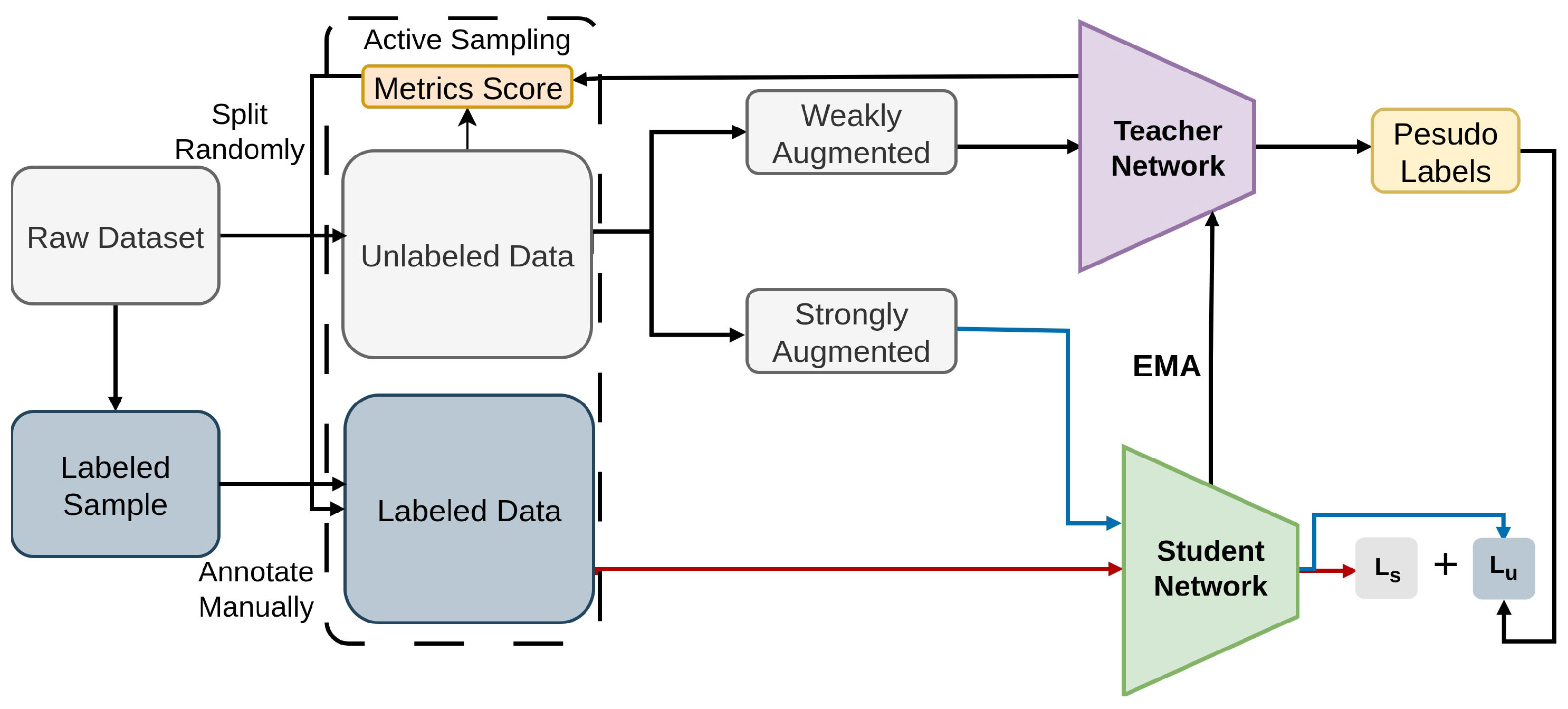

2.2.12. Active Teacher

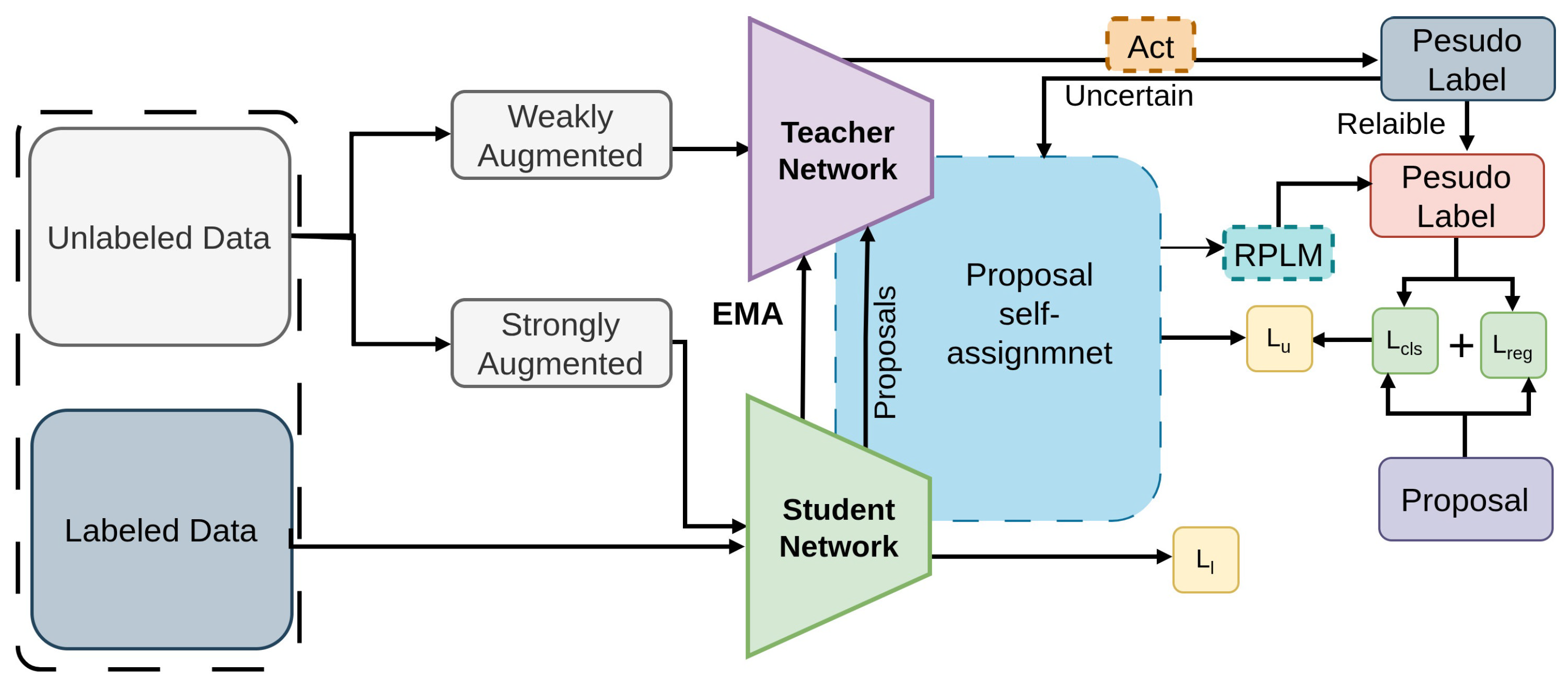

2.2.13. PseCo

2.2.14. CrossRectify

2.2.15. Label Match

2.2.16. ACRST

2.2.17. SED

2.2.18. SCMT

2.3. End to End

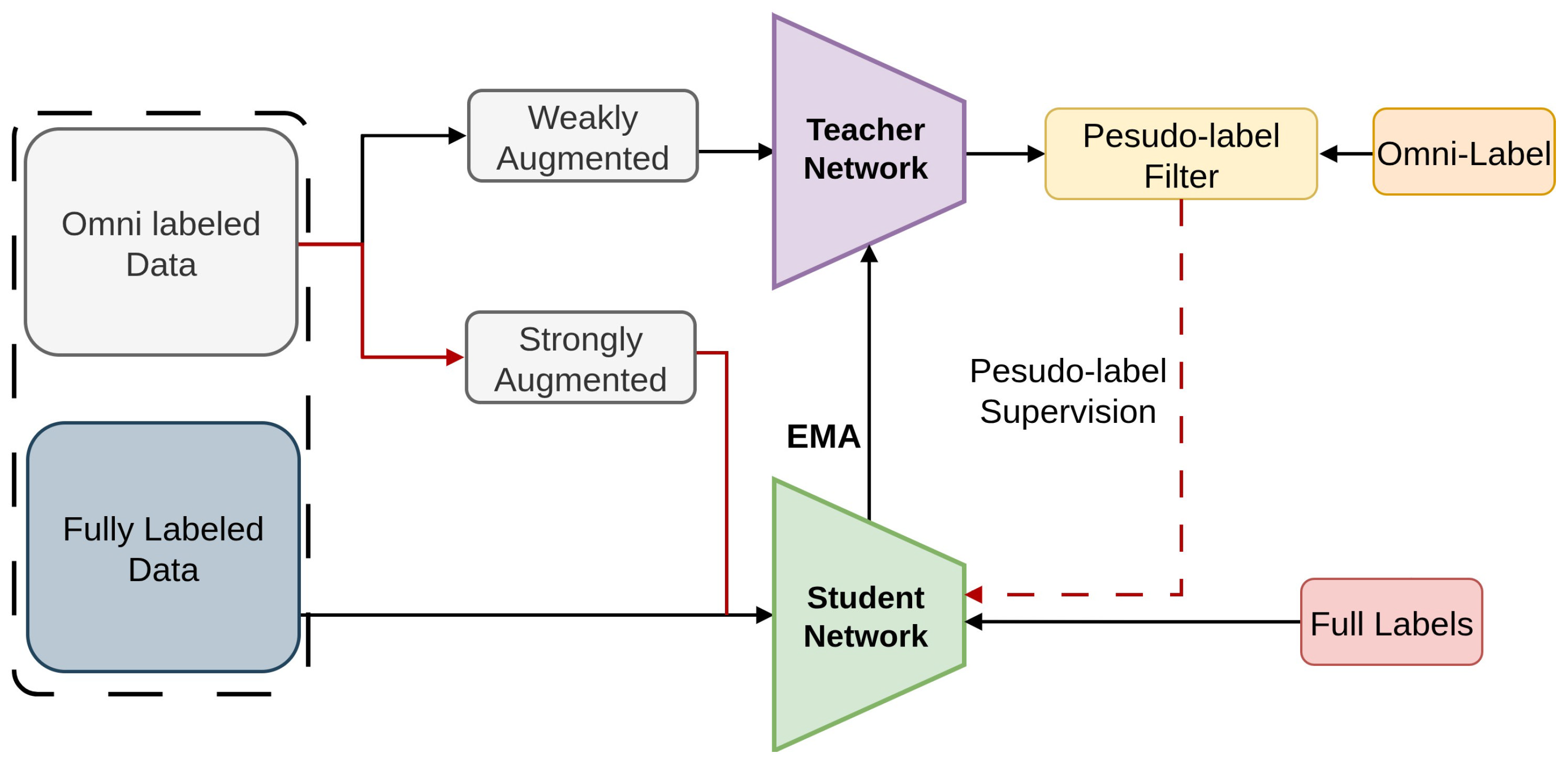

2.3.1. Omni-DETR

2.3.2. Semi-DETR

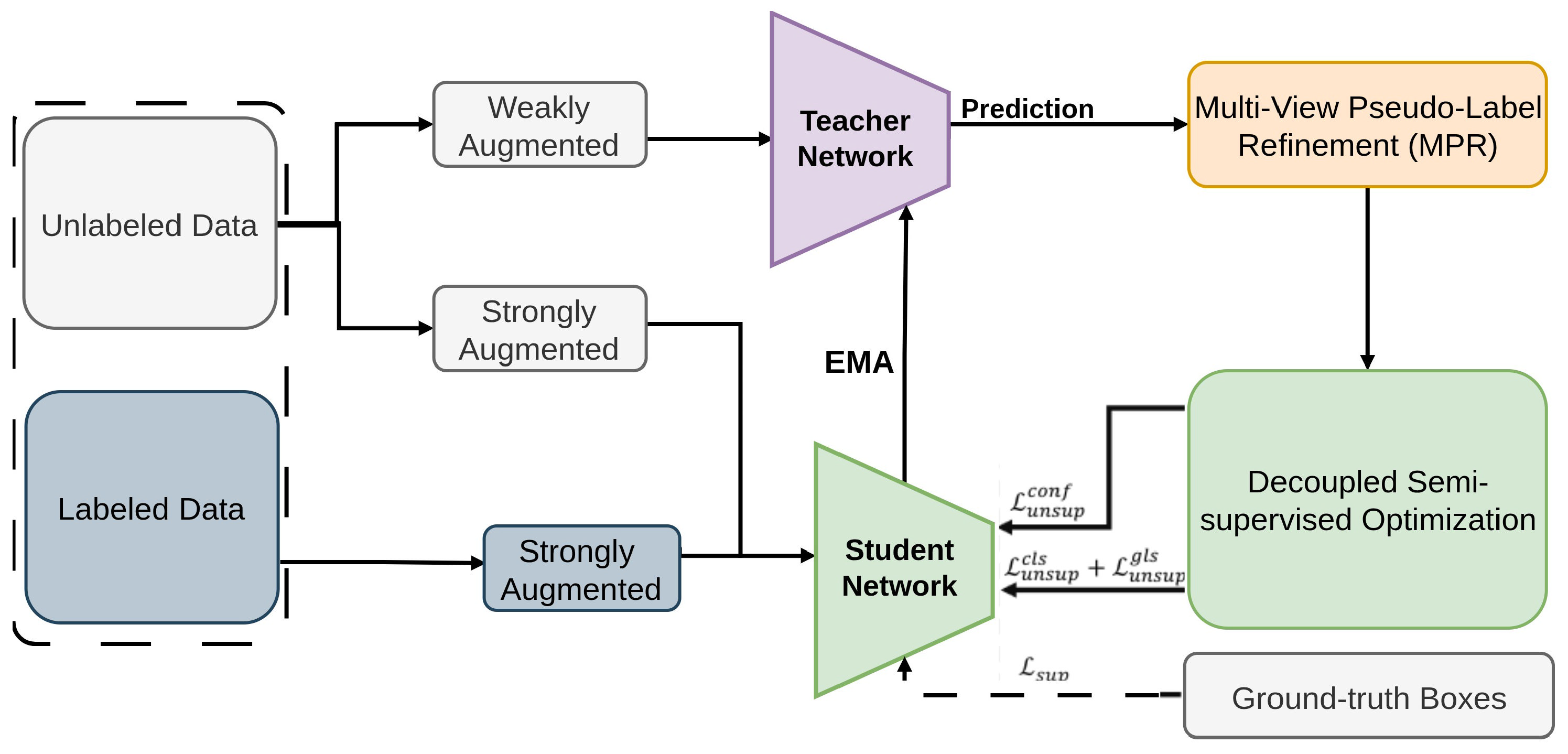

2.3.3. Sparse Semi-DETR

2.3.4. STEP-DETR

3. Loss Function

3.1. Smooth L1 Loss

3.2. Distillation Loss

3.3. Focal Loss

3.4. KL Divergence

3.5. Quality Focal Loss

3.6. Consistency Regularization Loss

3.7. Jensen–Shannon Divergence

3.8. Pseudo-Labeling Loss

3.9. Cross-Entropy Loss

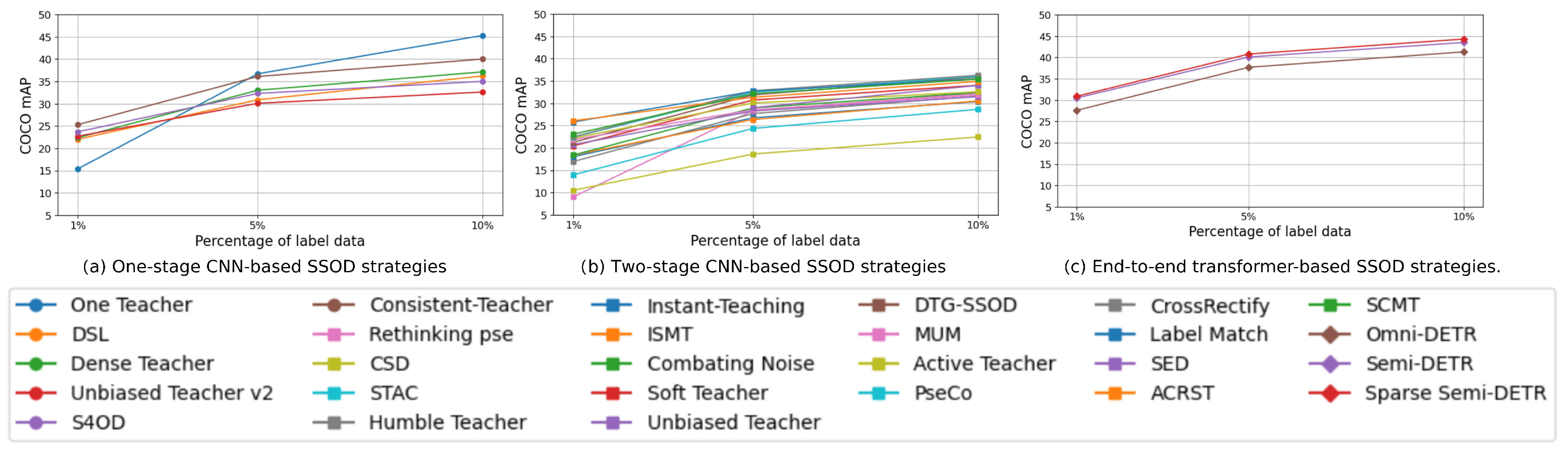

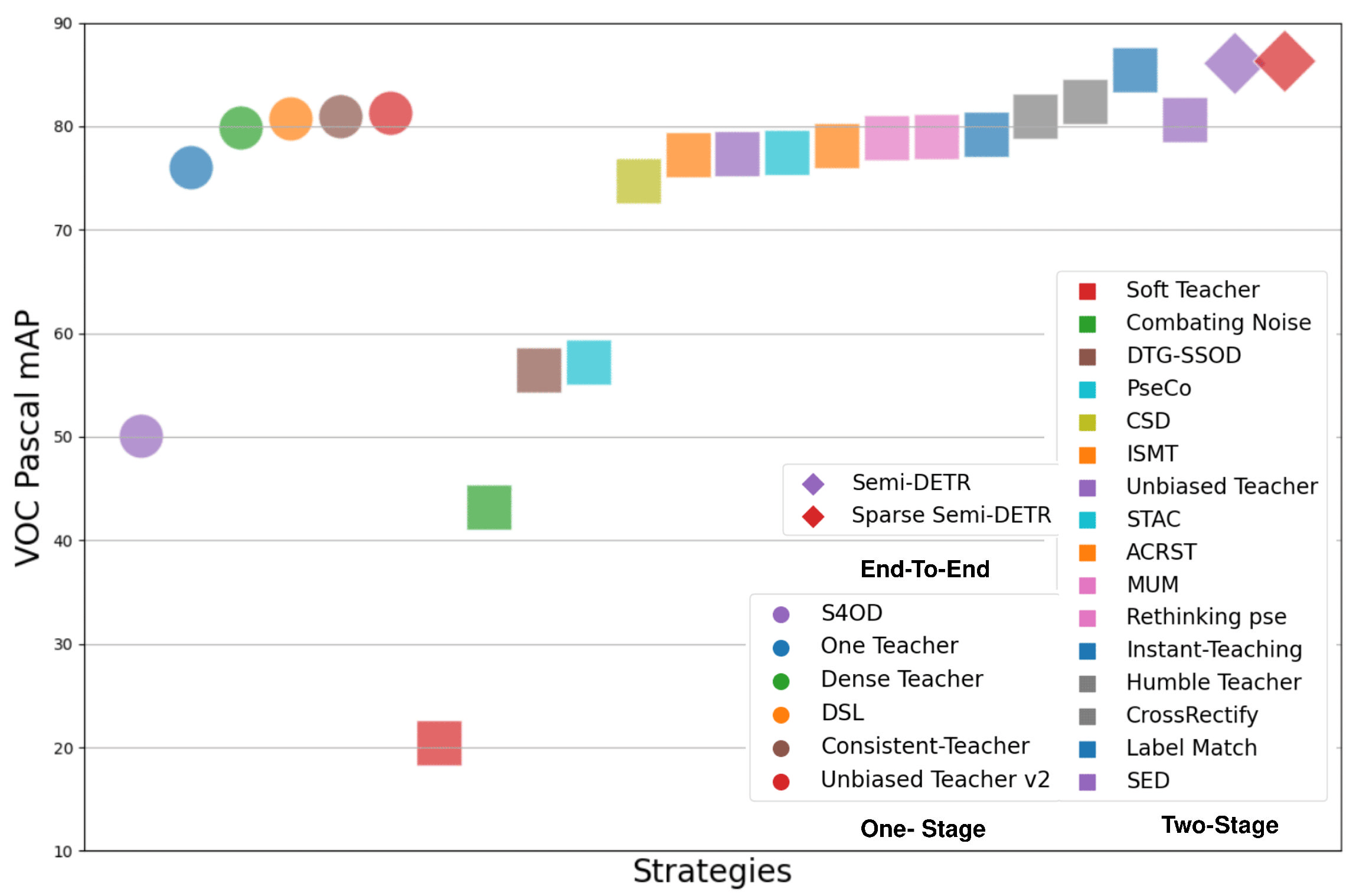

4. Datasets and Comparison

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Comparison

5. Open Challenges & Future Directions

6. Applications

6.1. Image Classification

6.2. Document Analysis

6.3. Three-Dimensional Object Detection

6.4. Network Traffic Classification

6.5. Speech Recognition

6.6. Drug Discovery and Bioinformatics

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, L.; Yu, D. Deep learning: Methods and applications. In Foundations and Trends® in Signal Processing; Now Publishers: Boston, MA, USA; Delft, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Oerlemans, A.; Lao, S.; Wu, S.; Lew, M.S. Deep learning for visual understanding: A review. Neurocomputing 2016, 187, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V, H. An overview of pattern recognition. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2022, 3, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C. Machine Learning in Pattern Recognition. Eur. J. Eng. Technol. Res. 2023, 8, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.H.; Chu, P.H.; Hsiao, P.Y. Data mining techniques and applications—A decade review from 2000 to 2011. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 11303–11311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F. A Study on the Application of Data Mining Techniques in the Management of Sustainable Education for Employment. Data Sci. J. 2023, 22, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Luxburg, U.; Schoelkopf, B. Statistical Learning Theory: Models, Concepts, and Results. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0810.4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.C.; Chen, C.H.; Shiao, Y.T.; Ciou, J.S.; Wu, T.N. Precision education with statistical learning and deep learning: A case study in Taiwan. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebis, G.; Egbert, D.; Shah, M. Review of computer vision education. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2003, 46, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canedo, D.; Neves, A.J.R. Facial Expression Recognition Using Computer Vision: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, D.; Koli, A.; Khatter, K.; Singh, S. Natural Language Processing: State of The Art, Current Trends and Challenges. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 82, 3713–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.H. Natural Language Processing: Recent Development and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveena, M.; Jaiganesh, V. A Literature Review on Supervised Machine Learning Algorithms and Boosting Process. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2017, 169, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasteski, V. An overview of the supervised machine learning methods. Horizons B 2017, 4, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mrabet, M.A.; El Makkaoui, K.; Faize, A. Supervised Machine Learning: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technologies and Networking (CommNet), Rabat, Morocco, 3–5 December 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouali, Y.; Hudelot, C.; Tami, M. An Overview of Deep Semi-Supervised Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.05278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Azeem Hashmi, K.; Stricker, D.; Liwicki, M.; Zeshan Afzal, M. Towards End-to-End Semi-Supervised Table Detection with Deformable Transformer. In Proceedings of the Document Analysis and Recognition—ICDAR 2023: 17th International Conference, San José, CA, USA, 21–26 August 2023; Proceedings, Part II. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allabadi, G.; Lucic, A.; Pao-Huang, P.; Wang, Y.X.; Adve, V. Semi-Supervised Object Detection in the Open World. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.; Bahk, S.; Kim, H.S. UpCycling: Semi-supervised 3D Object Detection without Sharing Raw-level Unlabeled Scenes. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2211.11950. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J.; Shi, S.; Wang, X.; Li, H. 3D Object Detection for Autonomous Driving: A Comprehensive Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2206.09474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Li, H.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Benediktsson, J.A. A novel semi-supervised learning framework for hyperspectral image classification. Int. J. Wavelets Multiresolut. Inf. Process. 2016, 14, 1640005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kou, P.; Ma, M.; Yang, H.; Huang, S.; Yang, Z. Application of Semi-Supervised Learning in Image Classification: Research on Fusion of Labeled and Unlabeled Data. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 27331–27343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, G.; Sinkovics, K.; Watsham, T.; Rolnick, D.; Walters, T.C. Semi-Supervised Object Detection for Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2nd AAAI Workshop on AI for Agriculture and Food Systems, Virtual, 14 February 2023; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=AR4SAOzcuz (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Yousaf, A.; Sazonov, E. Food Intake Detection in the Face of Limited Sensor Signal Annotations. In Proceedings of the 2024 Tenth International Conference on Communications and Electronics (ICCE), Danang, Vietnam, 31 July–2 August 2024; pp. 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, D.; Rieder, R. Computer vision and artificial intelligence in precision agriculture for grain crops: A systematic review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 153, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngobeni, R.; Sadare, O.; Daramola, M.O. Synthesis and Evaluation of HSOD/PSF and SSOD/PSF Membranes for Removal of Phenol from Industrial Wastewater. Polymers 2021, 13, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikhpour, R.; Sarram, M.A.; Gharaghani, S.; Chahooki, M.A.Z. A Survey on semi-supervised feature selection methods. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 64, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, K.; Narvekar, M. A Comprehensive Study and Analysis of Semi Supervised Learning Techniques. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 810–816. Available online: https://www.ijert.org/a-comprehensive-study-and-analysis-of-semi-supervised-learning-techniques (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Chi, S.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, J.; Kong, X.; Ding, K.; Weng, C.; Li, J. Semi-supervised learning to improve generalizability of risk prediction models. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 92, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mey, A.; Loog, M. Improved Generalization in Semi-Supervised Learning: A Survey of Theoretical Results. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 4747–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sahoo, D.; Hoi, S.C.H. Recent Advances in Deep Learning for Object Detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.03673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnavi, K.; Reddy, G.; Reddy, T.; Iyengar, N.; Shaik, S. Real-time Object Detection Using Deep Learning. J. Adv. Math. Comput. Sci. 2023, 38, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, T.; Khemchandani, V. Feature Engineering (FE) Tools and Techniques for Better Classification Performance. Int. J. Innov. Eng. Technol. 2019, 8, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, B.; Aruldoss, C.K.; Murugan, R. Feature Extraction and Object Detection Using Fast-Convolutional Neural Network for Remote Sensing Satellite Image. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2022, 50, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambo, F.L.; Haruna, A.S.; Muhammad, U.S.; Abdullahi, A.A.; Ahmed, B.A.; Dabai, U.S. Advances, Challenges and Opportunities in Deep Learning Approach for Object Detection: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Multidisciplinary Engineering and Applied Science (ICMEAS), Abuja, Nigeria, 1–3 November 2023; Volume 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkin, E.; Yadikar, N.; Muhtar, Y.; Ubul, K. A Survey of Object Detection Based on CNN and Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (PRML), Chengdu, China, 16–18 July 2021; pp. 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albawi, S.; Mohammed, T.A.; Al-Zawi, S. Understanding of a convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Engineering and Technology (ICET), Antalya, Turkey, 21–23 August 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogin, M.; Madhulika, M.S.; Divya, G.; Meghana, R.; Apoorva, S. Feature Extraction using Convolution Neural Networks (CNN) and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th Swiss Conference on Data Science (SDS), Bangalore, India, 18–19 May 2018; pp. 2319–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.M.; Ray, N. End-to-end Learning of Convolutional Neural Net and Dynamic Programming for Left Ventricle Segmentation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1812.00328. [Google Scholar]

- Synnaeve, G.; Xu, Q.; Kahn, J.; Likhomanenko, T.; Grave, E.; Pratap, V.; Sriram, A.; Liptchinsky, V.; Collobert, R. End-to-end ASR: From Supervised to Semi-Supervised Learning with Modern Architectures. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1911.08460. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Chang, V.; Hawash, H.; Chakrabortty, R.K.; Ryan, M. FSS-2019-nCov: A deep learning architecture for semi-supervised few-shot segmentation of COVID-19 infection. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 212, 106647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapelle, O.; Sindhwani, V.; Keerthi, S.S. Optimization Techniques for Semi-Supervised Support Vector Machines. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 203–233. [Google Scholar]

- Frommknecht, T.; Zipf, P.A.; Fan, Q.; Shvetsova, N.; Kuehne, H. Augmentation Learning for Semi-Supervised Classification. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.01956. [Google Scholar]

- Mumuni, A.; Mumuni, F. Data augmentation: A comprehensive survey of modern approaches. Array 2022, 16, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, D.; Carlini, N.; Cubuk, E.D.; Kurakin, A.; Sohn, K.; Zhang, H.; Raffel, C. ReMixMatch: Semi-Supervised Learning with Distribution Alignment and Augmentation Anchoring. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1911.09785. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Dai, Z.; Hovy, E.; Luong, M.T.; Le, Q.V. Unsupervised Data Augmentation for Consistency Training. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1904.12848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pise, N.N.; Kulkarni, P. A Survey of Semi-Supervised Learning Methods. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Security, Suzhou, China, 13–17 December 2008; Volume 2, pp. 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Song, Z.; King, I.; Xu, Z. A Survey on Deep Semi-Supervised Learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 8934–8954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazo, E.; Ortego, D.; Albert, P.; O’Connor, N.E.; McGuinness, K. Pseudo-Labeling and Confirmation Bias in Deep Semi-Supervised Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Likhomanenko, T.; Kahn, J.; Hannun, A.; Synnaeve, G.; Collobert, R. Iterative Pseudo-Labeling for Speech Recognition. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.09267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Gao, D.; Cheng, G.; Povey, D.; Zhang, P.; Yan, Y. Alternative Pseudo-Labeling for Semi-Supervised Automatic Speech Recognition. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2023, 31, 3320–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Lou, J.; Xiong, L.; Shahabi, C. SemiFed: Semi-supervised Federated Learning with Consistency and Pseudo-Labeling. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.09412. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. FCOS: Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.01355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1506.01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Yuan, Y.; He, H.; Wu, X.; Yu, H.; Lin, W.; Sun, L.; Zhang, C.; Hu, H. DETRs with Hybrid Matching. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2207.13080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Ni, L.M.; Zhang, L. DN-DETR: Accelerate DETR Training by Introducing Query DeNoising. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.01305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Hashmi, K.A.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Object Detection with Transformers: A Review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.04670. [Google Scholar]

- Hai Son, L.; Allauzen, A.; Yvon, F. Measuring the influence of long range dependencies with neural network language models. In Proceedings of the WLM@NAACL-HLT, Montréal, QC, Canada, 8 June 2012; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierlboeck, M.; Dunbar, D.; Nilchiani, R. Natural Language Processing to Extract Contextual Structure from Requirements. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon), Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–28 April 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.M.; Luque, F.; Zayat, D.; Kondratzky, M.; Moro, A.; Serrati, P.; Zajac, J.; Miguel, P.; Debandi, N.; Gravano, A.; et al. Assessing the impact of contextual information in hate speech detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2210.00465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gupta, A. Spatial Memory for Context Reasoning in Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 4106–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deléarde, R.; Kurtz, C.; Wendling, L. Description and recognition of complex spatial configurations of object pairs with Force Banner 2D features. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 123, 108410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosang, J.; Benenson, R.; Schiele, B. Learning non-maximum suppression. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.02950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Liang, M.; Qin, J.; Zhong, S.; Lin, L. Understanding Self-attention Mechanism via Dynamical System Perspective. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.09939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Tang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cun, X.; Cao, J.; Li, J.; Lee, T.Y. Make-Your-Anchor: A Diffusion-based 2D Avatar Generation Framework. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.16510. [Google Scholar]

- Hoanh, N.; Pham, T.V. Focus-Attention Approach in Optimizing DETR for Object Detection from High-Resolution Images. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 296, 111939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Ramaiah, C.; Xu, R.; Xiong, C. Proposal Learning for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Virtual, 5–9 January 2021; pp. 2290–2300. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:210699986 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Shehzadi, T.; Ifza, I.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. FD-SSD: Semi-supervised Detection of Bone Fenestration and Dehiscence in Intraoral Images. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Understanding and Analysis (MIUA) 2025, Leeds, UK, 15–17 July 2025; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15917. [Google Scholar]

- Shehzadi, T.; Hashmi, K.A.; Pagani, A.; Liwicki, M.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Mask-Aware Semi-Supervised Object Detection in Floor Plans. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Tan, X.; Han, J.; Ding, E.; Wang, J.; Li, G. Semi-DETR: Semi-Supervised Object Detection with Detection Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 23809–23818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Hashmi, K.A.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Sparse Semi-DETR: Sparse Learnable Queries for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.01819. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Cai, Z.; Yang, H.; Swaminathan, G.; Vasconcelos, N.; Schiele, B.; Soatto, S. Omni-DETR: Omni-Supervised Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 9357–9366. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:247792844 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Li, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liang, D.; Zhang, S. PseCo: Pseudo Labeling and Consistency Training for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.16317. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Kwak, N. Consistency-based Semi-supervised Learning for Object detection. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:202782547 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Sohn, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.L.; Zhang, H.; Lee, C.Y.; Pfister, T. A Simple Semi-Supervised Learning Framework for Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.04757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, W.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y. Humble Teachers Teach Better Students for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.10456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yu, C.; Wang, Z.; Qian, Q.; Li, H. Instant-Teaching: An End-to-End Semi-Supervised Object Detection Framework. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.11402. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Wei, F.; Bai, X.; Liu, Z. End-to-End Semi-Supervised Object Detection with Soft Teacher. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.09018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.C.; Ma, C.Y.; He, Z.; Kuo, C.W.; Chen, K.; Zhang, P.; Wu, B.; Kira, Z.; Vajda, P. Unbiased Teacher for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.09480. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:231951546 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Zhang, F.; Pan, T.; Wang, B. Semi-Supervised Object Detection with Adaptive Class-Rebalancing Self-Training. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.05031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S. Combating noise: Semi-supervised learning by region uncertainty quantification. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS ’21, Virtual, 6–14 December 2021; Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3540261.3540991 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Kim, J.; Jang, J.; Seo, S.; Jeong, J.; Na, J.; Kwak, N. MUM: Mix Image Tiles and UnMix Feature Tiles for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2111.10958. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Wei, X.; Wang, B.; Hua, X.S.; Zhang, L. Interactive Self-Training with Mean Teachers for Semi-supervised Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 5937–5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Pan, X.; Ye, Q.; Tang, F.; Dong, W.; Xu, C. CrossRectify: Leveraging Disagreement for Semi-supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.10734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Mu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, T.; Yu, Y.; Luo, P. Scale-Equivalent Distillation for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.12244. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Chen, W.; Yang, S.; Xuan, Y.; Song, J.; Xie, D.; Pu, S.; Song, M.; Zhuang, Y. Label Matching Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.06608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liang, D.; Zhang, S. DTG-SSOD: Dense Teacher Guidance for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.05536. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wu, Z.; Shrivastava, A.; Davis, L.S. Rethinking Pseudo Labels for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.00168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, P.; Lin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, Y.; Luo, G.; Sun, X.; Cao, L.; Fu, R.; Xu, Q.; Ji, R. Active Teacher for Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Tian, J.; Hao, Z.; He, Y.; Ren, X. SCMT: Self-Correction Mean Teacher for Semi-supervised Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-22; Vienna, Austria, 23–29 July 2022, Raedt, L.D., Ed.; International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 2022; pp. 1488–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Feng, L.; Fang, S.; Lyu, C.; Chen, K.; Zhang, W. Consistent-Teacher: Towards Reducing Inconsistent Pseudo-targets in Semi-supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2209.01589. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Li, P.; Chen, X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; Hua, X.S. Dense Learning based Semi-Supervised Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 4805–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Mao, W.; Li, Z.; Yu, H.; Sun, J. Dense Teacher: Dense Pseudo-Labels for Semi-supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.02541. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, F.; Song, X.; Xing, T.; Hu, R.; Chai, H.; Xu, P.; Zhang, G. S4OD: Semi-Supervised learning for Single-Stage Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.04492. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.C.; Ma, C.Y.; Kira, Z. Unbiased Teacher v2: Semi-supervised Object Detection for Anchor-free and Anchor-based Detectors. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.09500. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, L.; Sun, X.; Ji, R. Towards End-to-end Semi-supervised Learning for One-stage Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.11299. [Google Scholar]

- Cubuk, E.D.; Zoph, B.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. RandAugment: Practical automated data augmentation with a reduced search space. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.13719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, M.; Javanmardi, M.; Tasdizen, T. Regularization With Stochastic Transformations and Perturbations for Deep Semi-Supervised Learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.04586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Zheng, L.; Kang, G.; Li, S.; Yang, Y. Random Erasing Data Augmentation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.04896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, K.; Berthelot, D.; Li, C.L.; Zhang, Z.; Carlini, N.; Cubuk, E.D.; Kurakin, A.; Zhang, H.; Raffel, C. FixMatch: Simplifying Semi-Supervised Learning with Consistency and Confidence. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.07685. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X. Semi-Supervised Learning Literature Survey; Technical Report 1530; Computer Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2005. Available online: https://minds.wisconsin.edu/handle/1793/60444 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Mey, A.; Loog, M. Improvability Through Semi-Supervised Learning: A Survey of Theoretical Results. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1908.09574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmler, N.; Sager, P.; Andermatt, P.; Chavarriaga, R.; Schilling, F.P.; Rosenthal, M.; Stadelmann, T. A Survey of Un-, Weakly-, and Semi-Supervised Learning Methods for Noisy, Missing and Partial Labels in Industrial Vision Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th Swiss Conference on Data Science (SDS), Lucerne, Switzerland, 9 June 2021; pp. 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.F.F.D.; Coletta, L.F.S.; Hruschka, E.R. A Survey and Comparative Study of Tweet Sentiment Analysis via Semi-Supervised Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2016, 49, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, V.J.; Nithya, D.L. A Survey On Semi-Supervised Learning Techniques. Int. J. Comput. Trends Technol. 2014, 8, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Engelen, J.E.; Hoos, H.H. A survey on semi-supervised learning. Mach. Learn. 2019, 109, 373–440. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:254738406 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Qi, G.J.; Luo, J. Small Data Challenges in Big Data Era: A Survey of Recent Progress on Unsupervised and Semi-Supervised Methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 44, 2168–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmarje, L.; Santarossa, M.; Schroder, S.M.; Koch, R. A Survey on Semi-, Self- and Unsupervised Learning for Image Classification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 82146–82168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mancini, M.; Zhu, X.; Akata, Z. Semi-Supervised and Unsupervised Deep Visual Learning: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.11296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebli, A.; Djebbar, A.; Marouani, H.F. Semi-Supervised Learning for Medical Application: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Applied Smart Systems (ICASS), Medea, Algeria, 24–25 November 2018; pp. 1–9. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:67876194 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Gomes, H.M.; Grzenda, M.; Mello, R.; Read, J.; Le Nguyen, M.H.; Bifet, A. A Survey on Semi-supervised Learning for Delayed Partially Labelled Data Streams. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Ramirez, S.; Yang, S.; Elizondo, D. Semisupervised Deep Learning for Image Classification With Distribution Mismatch: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 1015–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Yang, X.; Xu, Z.; King, I. Graph-Based Semi-Supervised Learning: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 8174–8194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, M.C.; Salmanoglu, B.; Guzel, M.S.; Gursoy, B.; Bostanci, G.E. Evaluation of YOLO Models with Sliced Inference for Small Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.04799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. YOLOX: Exceeding YOLO Series in 2021. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.08430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Gupta, A.; Ong, Y.S. Multi-Task Learning with Multi-Task Optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.16162. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, B.; Fan, H.; Grauman, K.; Feichtenhofer, C. Multiview Pseudo-Labeling for Semi-supervised Learning from Video. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.00682. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, D.; Huang, Y.; Xie, J.; Honig, E.; Xu, M.; Xue, S.; Lin, P.; Zhou, S.; Zhong, S.; Zheng, N.; et al. Dual-Space Optimization: Improved Molecule Sequence Design by Latent Prompt Transformer. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.17179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ke, Z.; Lau, R. Towards Self-Adaptive Pseudo-Label Filtering for Semi-Supervised Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.09774. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Ryoo, K.; Lee, G.; Cho, S.; Seo, J.; Kim, D.; Cho, H.; Kim, S. AggMatch: Aggregating Pseudo Labels for Semi-Supervised Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.10444. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Kukleva, A.; Schiele, B. Revisiting Consistency Regularization for Semi-Supervised Learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.05825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Ma, T.; Ren, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, J. Sparse Generation: Making Pseudo Labels Sparse for Point Weakly Supervised Object Detection on Low Data Volume. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025—2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Luo, H.; Zhang, K.; Lu, J.; Xiong, Z. Pseudo-label growth dictionary pair learning for crowd counting. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 8913–8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Kahng, H.; Kim, S.B. Deep Semi-Supervised Regression via Pseudo-Label Filtering and Calibration. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 161, 111670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, H.; Li, C.; Wang, S. Analysis of Anchor-Based and Anchor-Free Object Detection Methods Based on Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Beijing, China, 13–16 October 2020; pp. 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1708.02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, A.; Wang, H. A Feature Extraction Algorithm for Enhancing Graphical Local Adaptive Threshold. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Computing Theories and Application: 18th International Conference, ICIC 2022, Xi’an, China, 7–11 August 2022; Proceedings, Part I. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, S.; Liu, X. Overfitting Mechanism and Avoidance in Deep Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.06566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Scott, M.R.; Huang, W. TOOD: Task-aligned One-stage Object Detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.07755. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yoshie, O.; Sun, J. OTA: Optimal Transport Assignment for Object Detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.14259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Luo, R.; Mao, J.; Xiao, T.; Jiang, Y. Acquisition of Localization Confidence for Accurate Object Detection. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.11590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampiconi, L.; Elwood, A.; Leonardi, M.; Mohamed, A.; Rozza, A. A survey and taxonomy of loss functions in machine learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.05579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksuz, K.; Cam, B.C.; Kalkan, S.; Akbas, E. Imbalance Problems in Object Detection: A Review. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 3388–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Bu, X.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, T.; Yan, J. Large-Scale Object Detection in the Wild From Imbalanced Multi-Labels. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 9706–9715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, K.; Loy, C.C.; Lin, D. Prime Sample Attention in Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 11580–11588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, J.; Lin, W.; See, J.; Wang, J.; Duan, L.; Chen, Z.; He, C.; Zou, J. Towards Accurate One-Stage Object Detection With AP-Loss. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 5114–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisdom, S.; Hershey, J.R.; Wilson, K.W.; Thorpe, J.; Chinen, M.; Patton, B.; Saurous, R.A. Differentiable Consistency Constraints for Improved Deep Speech Enhancement. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2019—2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Brighton, UK, 12–17 May 2018; pp. 900–904. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:53739933 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Shen, Z.; Cao, P.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Zaiane, O.R. Co-training with High-Confidence Pseudo Labels for Semi-supervised Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.04465. [Google Scholar]

- Zoph, B.; Cubuk, E.D.; Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.Y.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Learning Data Augmentation Strategies for Object Detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.11172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, H. Probability of error of some adaptive pattern-recognition machines. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1965, 11, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, G.J. Iterative Reclassification Procedure for Constructing an Asymptotically Optimal Rule of Allocation in Discriminant Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1975, 70, 365–369. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2285824 (accessed on 5 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Tarvainen, A.; Valpola, H. Mean teachers are better role models: Weight-averaged consistency targets improve semi-supervised deep learning results. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1703.01780. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, K.; Wang, L.; Zhou, S.; Hua, G.; Tang, W. Learning from Noisy Pseudo Labels for Semi-Supervised Temporal Action Localization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 10126–10135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Rong, Y.; Wang, W.; Tsung, F. Deep Insights into Noisy Pseudo Labeling on Graph Data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.01634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Mou, L.; Chen, J.; Bo, Y.; Emery, W.J. Incorporating Metric Learning and Adversarial Network for Seasonal Invariant Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 2720–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoph, B.; Ghiasi, G.; Lin, T.Y.; Cui, Y.; Liu, H.; Cubuk, E.D.; Le, Q.V. Rethinking pre-training and self-training. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS ’20, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/proceedings/10.5555/3495724 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- He, Y.; Chen, W.; Liang, K.; Tan, Y.; Liang, Z.; Guo, Y. Pseudo-label Correction and Learning For Semi-Supervised Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.02998. [Google Scholar]

- Gevorgyan, Z. SIoU Loss: More Powerful Learning for Bounding Box Regression. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinker, F. Exponential moving average versus moving exponential average. Math. Semesterber. 2011, 58, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelot, D.; Carlini, N.; Goodfellow, I.; Papernot, N.; Oliver, A.; Raffel, C. MixMatch: A Holistic Approach to Semi-Supervised Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.02249. [Google Scholar]

- Bodla, N.; Singh, B.; Chellappa, R.; Davis, L.S. Soft-NMS—Improving Object Detection With One Line of Code. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04503. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, V.; Kawaguchi, K.; Lamb, A.; Kannala, J.; Solin, A.; Bengio, Y.; Lopez-Paz, D. Interpolation consistency training for semi-supervised learning. Neural Netw. 2022, 145, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, G.; Laine, S.; Aila, T.; Mackiewicz, M.; Finlayson, G. Semi-supervised semantic segmentation needs strong, varied perturbations. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1906.01916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.; Chen, S.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, J. Generalized Focal Loss: Learning Qualified and Distributed Bounding Boxes for Dense Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noord, N.; Postma, E. Learning scale-variant and scale-invariant features for deep image classification. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.01255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, Y.M.; Rupprecht, C.; Vedaldi, A. Self-labelling via simultaneous clustering and representation learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1911.05371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.R.; Litany, O.; He, K.; Guibas, L.J. Deep Hough Voting for 3D Object Detection in Point Clouds. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Wei, C.; Gaidon, A.; Arechiga, N.; Ma, T. Learning Imbalanced Datasets with Label-Distribution-Aware Margin Loss. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.07413. [Google Scholar]

- Higashimoto, R.; Yoshida, S.; Horihata, T.; Muneyasu, M. Unbiased Pseudo-Labeling for Learning with Noisy Labels. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2024, 107, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhuang, S.; Zuccon, G. Large Language Models for Stemming: Promises, Pitfalls and Failures. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismailov, A.; Jalil, M.A.; Abdullah, Z.; Rahim, N.A. A comparative study of stemming algorithms for use with the Uzbek language. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on Computer and Information Sciences (ICCOINS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 15–17 August 2016; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; Yao, X.; Cheng, G. Semantic segmentation guided pseudo label mining and instance re-detection for weakly supervised object detection in remote sensing images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 119, 103301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, B.; Paliwal, M.; Nagwanshi, K.K. Study on Image Filtering—Techniques, Algorithm and Applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.06481. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Liang, D.; Hu, X.; Luo, P. Online Knowledge Distillation via Collaborative Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11017–11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiffert, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Hulse, J.V.; Napolitano, A. Resampling or Reweighting: A Comparison of Boosting Implementations. In Proceedings of the 2008 20th IEEE International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence, Dayton, OH, USA, 3–5 November 2008; Volume 1, pp. 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Gu, H.; Mazurowski, M.A. How to Efficiently Annotate Images for Best-Performing Deep Learning Based Segmentation Models: An Empirical Study with Weak and Noisy Annotations and Segment Anything Model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.10600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.12872. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable Transformers for End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- M., A.; Govindharaju, K.; John, A.; Mohan, S.; Ahmadian, A.; Ciano, T. A hybrid learning approach for the stage-wise classification and prediction of COVID-19 X-ray images. Expert Syst. 2022, 39, e12884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Yao, K.; Feng, H.; Han, J.; Ding, E.; Zeng, G.; Wang, J. Group DETR: Fast DETR Training with Group-Wise One-to-Many Assignment. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2207.13085. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Xing, X.; Xu, D.; Kong, X.; Zhou, L. Conflict-Based Cross-View Consistency for Semi-Supervised Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.01276. [Google Scholar]

- Mosbah, M. Query Refinement into Information Retrieval Systems: An Overview. J. Inf. Organ. Sci. 2023, 47, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Hashmi, K.A.; Sarode, S.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. STEP-DETR: Advancing DETR-based Semi-Supervised Object Detection with Super Teacher and Pseudo-Label Guided Text Queries. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–23 October 2025; pp. 3069–3079. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/ICCV2025/html/Shehzadi_STEP-DETR_Advancing_DETR-based_Semi-Supervised_Object_Detection_with_Super_Teacher_and_ICCV_2025_paper.html (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Sutanto, A.R.; Kang, D.K. A Novel Diminish Smooth L1 Loss Model with Generative Adversarial Network. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Human Computer Interaction: 12th International Conference, IHCI 2020, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 24–26 November 2020; Proceedings, Part I. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Sun, J. Points as Queries: Weakly Semi-supervised Object Detection by Points. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 8819–8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Zhang, X. Knowledge Transfer for Object Detection. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1549, 052119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banitalebi-Dehkordi, A. Knowledge Distillation for Low-Power Object Detection: A Simple Technique and Its Extensions for Training Compact Models Using Unlabeled Data. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yao, Y.; Tan, J.; Zhang, G.; Yu, F.; Lu, J.; Luo, Y. Equalized Focal Loss for Dense Long-Tailed Object Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.02593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Ming, Q.; Wang, W.; Tian, Q.; Yan, J. Learning High-Precision Bounding Box for Rotated Object Detection via Kullback-Leibler Divergence. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2106.01883. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, G.; Yoo, J.; Choi, J.; Kwak, N. KL-Divergence-Based Region Proposal Network for Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.11220. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, J. Generalized Focal Loss V2: Learning Reliable Localization Quality Estimation for Dense Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.12885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Osorio, J.K.; Posso-Murillo, S.; Sanchez-Giraldo, L.G. The Representation Jensen-Shannon Divergence. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.16446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F. On the Jensen–Shannon Symmetrization of Distances Relying on Abstract Means. Entropy 2019, 21, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, T.; Heo, J.p. Cross-Loss Pseudo Labeling for Semi-Supervised Segmentation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 96761–96772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, A.; Mohri, M.; Zhong, Y. Cross-Entropy Loss Functions: Theoretical Analysis and Applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.07288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Bourdev, L.; Girshick, R.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Zitnick, C.L.; Dollár, P. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1405.0312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everingham, M.; Van Gool, L.; Williams, C.; Winn, J.; Zisserman, A. The Pascal Visual Object Classes (VOC) challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Niu, Y.; Miao, C.; Hua, X.S.; Zhang, H. On Non-Random Missing Labels in Semi-Supervised Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.14923. [Google Scholar]

- Solatidehkordi, Z.; Zualkernan, I. Survey on Recent Trends in Medical Image Classification Using Semi-Supervised Learning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inés, A.; Domínguez, C.; Heras, J.; Mata, E.; Pascual, V. Biomedical image classification made easier thanks to transfer and semi-supervised learning. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 198, 105782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Shehzadi, T.; Farooq, A.; Ilyas, K. Protein active site prediction for early drug discovery and designing. Int. Rev. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2021, 13, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Majid, A.; Hameed, M.; Farooq, A.; Yousaf, A. Intelligent predictor using cancer-related biologically information extraction from cancer transcriptomes. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Recent Advances in Electrical Engineering & Computer Sciences (RAEE & CS), Islamabad, Pakistan, 20–22 October 2020; Volume 5, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; He, F.; Yang, Y.; Hu, F. Semi-Supervised Representation Learning for Remote Sensing Image Classification Based on Generative Adversarial Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 54135–54144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Tang, K.; Li, M.; Zhong, Y.; Qin, A.K. Collaborative Active and Semisupervised Learning for Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 53, 2384–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gang, H.; Ma, H.; Tomizuka, M.; Choi, C. Important Object Identification with Semi-Supervised Learning for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 2913–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yan, J.; Huang, W.; Ge, W.; Liu, H.; Yin, H. Robust Object Detection for Autonomous Driving Based on Semi-supervised Learning. Secur. Saf. 2024, 3, 2024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Hashmi, K.A.; Stricker, D.; Liwicki, M.; Afzal, M.Z. Bridging the Performance Gap between DETR and R-CNN for Graphical Object Detection in Document Images. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.13526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Sarode, S.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Towards End-to-End Semi-supervised Table Detection with Semantic Aligned Matching Transformer. In Proceedings of the Document Analysis and Recognition—ICDAR 2024; Athens, Greece, 30 August–4 September 2024, Barney~Smith, E.H., Liwicki, M., Peng, L., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. A Hybrid Approach for Document Layout Analysis in Document images. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.17888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Ifza, I.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Efficient Additive Attention for Transformer-based Semi-supervised Document Layout Analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–23 October 2025; pp. 3495–3503. [Google Scholar]

- Kallempudi, G.; Hashmi, K.A.; Pagani, A.; Liwicki, M.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Toward Semi-Supervised Graphical Object Detection in Document Images. Future Internet 2022, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, K.A.; Pagani, A.; Liwicki, M.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. CasTabDetectoRS: Cascade Network for Table Detection in Document Images with Recursive Feature Pyramid and Switchable Atrous Convolution. J. Imaging 2021, 7, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.; Agne, S.; Wolf, I.; Dengel, A.; Ahmed, S. DeepDeSRT: Deep Learning for Detection and Structure Recognition of Tables in Document Images. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th IAPR International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), Kyoto, Japan, 9–15 November 2017; Volume 1, pp. 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Gao, L.; Yi, X.; Tang, Z. A Table Detection Method for PDF Documents Based on Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 12th IAPR Workshop on Document Analysis Systems (DAS), Santorini, Greece, 11–14 April 2016; pp. 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Gao, L.; Bai, K.; Qiu, R.; Tao, X.; Tang, Z. A Table Detection Method for Multipage PDF Documents via Visual Seperators and Tabular Structures. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Beijing, China, 18–21 September 2011; pp. 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasar, T.; Barlas, P.; Adam, S.; Chatelain, C.; Paquet, T. Learning to Detect Tables in Scanned Document Images Using Line Information. In Proceedings of the 2013 12th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, Washington, DC, USA, 25–28 August 2013; pp. 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Ifza, I.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. DocSemi: Efficient Document Layout Analysis with Guided Queries. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–23 October 2025; pp. 7536–7546. [Google Scholar]

- Ehsan, I.; Shehzadi, T.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. End-to-End Semi-Supervised approach with Modulated Object Queries for Table Detection in Documents. Int. J. Doc. Anal. Recognit. 2024, 27, 363–378. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:269626070 (accessed on 5 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Luong, M.T.; Hovy, E.; Le, Q.V. Self-Training With Noisy Student Improves ImageNet Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cong, Y.; Litany, O.; Gao, Y.; Guibas, L.J. 3DIoUMatch: Leveraging IoU Prediction for Semi-Supervised 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 14610–14619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Fang, J.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.Z.; Shen, J.; Wang, W. Semi-supervised 3D Object Detection with Proficient Teachers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, A.; Guindel, C.; Beltrán, J.; García, F. BirdNet+: End-to-End 3D Object Detection in LiDAR Bird’s Eye View. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.04188. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Fu, H.; Tai, C.L. TransFusion: Robust LiDAR-Camera Fusion for 3D Object Detection with Transformers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.11496. [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika, A.; Vyas, A.; Rahmati, M.; Wang, Y. Multi-Camera 3D Object Detection for Autonomous Driving Using Deep Learning and Self-Attention Mechanism. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 64608–64620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ouyang, W.; Simonelli, A.; Ricci, E. 3D Object Detection from Images for Autonomous Driving: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2202.02980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Liang, Z.; He, M.; Peng, Y.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y. A federated semi-supervised learning approach for network traffic classification. Int. J. Netw. Manag. 2023, 33, e2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erman, J.; Mahanti, A.; Arlitt, M.; Cohen, I.; Williamson, C. Offline/realtime traffic classification using semi-supervised learning. Perform. Eval. 2007, 64, 1194–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, W.; Saleh, M.S.; Gull, M.N.; Raza, H.; Saeed, R.; Shehzadi, T. Geometric features and traffic dynamic analysis on 4-leg intersections. Int. Rev. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2024, 15, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Deng, X.; Tian, S.; Zhang, L.; Xue, K. A Knowledge Transfer-Based Semi-Supervised Federated Learning for IoT Malware Detection. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2023, 20, 2127–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Du, C. Semi-Supervised Deep Learning based Network Intrusion Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery (CyberC), Chongqing, China, 29–30 October 2020; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitin Washani, S.S. Speech Recognition System: A Review. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 115, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Rastogi, S. Speech recognition systems—A comprehensive study of concepts and mechanism. Acta Inform. Malays. 2019, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Malik, M.K.; Mehmood, K.; Makhdoom, I. Automatic speech recognition: A survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 9411–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, S.K.; Gawali, B.W.; Yannawar, P.Y. Article:A Review on Speech Recognition Technique. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2010, 10, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrawankar, U.; Thakare, V.M. Techniques for Feature Extraction In Speech Recognition System: A Comparative Study. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1305.1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safeel, M.; Sukumar, T.; Shashank, K.S.; Arman, M.D.; Shashidhar, R.; Puneeth, S.B. Sign Language Recognition Techniques—A Review. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference for Innovation in Technology (INOCON), Bangluru, India, 6–8 November 2020; pp. 1–9. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:230513563 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Rabiner, L. Applications of speech recognition in the area of telecommunications. In Proceedings of the 1997 IEEE Workshop on Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Proceedings, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 17 December 1997; pp. 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Embedded speech recognition applications in mobile phones: Status, trends, and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 31 March–4 April 2008; pp. 5352–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhu, F.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J. Seq3seq Fingerprint: Towards End-to-end Semi-supervised Deep Drug Discovery. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, and Health Informatics, BCB ’18, Washington, DC, USA, 29 August–1 September 2018; pp. 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Duan, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, F.X.; Pan, Y.; Wang, J. Predicting Drug-Drug Interactions Based on Integrated Similarity and Semi-Supervised Learning. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2022, 19, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Ho, T.B. Detecting disease genes based on semi-supervised learning and protein-protein interaction networks. Artif. Intell. Med. 2012, 54, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Lu, C.; Huang, Z.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Chen, E.; Lee, C. ASGN: An Active Semi-supervised Graph Neural Network for Molecular Property Prediction. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, KDD ’20, Virtual, 23–27 August 2020; pp. 731–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zheng, S.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, S.; Zeng, X. Semi-supervised deep learning for molecular clump verification. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 683, A104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuksa, P.P.; Qi, Y. Semi-Supervised Bio-Named Entity Recognition with Word-Codebook Learning. In Proceedings of the 2010 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM), Columbus, OH, USA, 29 April–1 May 2010; pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourreza Shahri, M.; Kahanda, I. Deep semi-supervised learning ensemble framework for classifying co-mentions of human proteins and phenotypes. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Supervised Learning Literature Survey [104] | 2008 | This survey examines the landscape of semi-supervised learning literature concentrating on diverse methodologies and applications. |

| A Survey On Semi-Supervised Learning Techniques [108] | 2014 | An Analysis investigates various techniques in semi-supervised learning, offering insights into their effectiveness and applications. |

| A Survey and Comparative Study of Tweet Sentiment Analysis via Semi-Supervised Learning [107] | 2016 | This study provides a thorough comparison and analysis of tweet sentiment methods employing semi-supervised learning techniques. |

| Semi-supervised learning for medical application: A survey [113] | 2018 | This paper delves into the integration of semi-supervised learning within medical contexts, offering insights into its applicability and potential advancements. |

| A survey on semi supervised learning [109] | 2019 | This comprehensive examination explores the domain of semi-supervised learning, shedding light on its practical implementations and advancements. |

| Improvability Through Semi-Supervised Learning: A Survey of Theoretical Results [105] | 2020 | This analysis investigates theoretical advancements facilitated by semi-supervised learning, exploring avenues for improvement within machine learning frameworks. |

| Small Data Challenges in Big Data Era: A Survey of Recent Progress on Unsupervised and Semi-Supervised Methods [110] | 2020 | This exploration examines recent progress in unsupervised and semi-supervised methods, addressing challenges posed by small data in the context of the big data era. |

| A Survey of Un-, Weakly-, and Semi-Supervised Learning Methods for Noisy, Missing and Partial Labels in Industrial Vision Applications [106] | 2021 | This survey evaluates unsupervised, weakly-supervised, and semi-supervised learning techniques designed to address problems caused by noisy, incomplete, and missing labels in industrial vision applications. |

| Semi-Supervised and Unsupervised Deep Visual Learning: A Survey [112] | 2022 | This study explores the field of deep visual learning, with a particular focus on semi-supervised and unsupervised methods. It aims to uncover key insights and advancements in these approaches. |

| A Survey on Semi-, Self- and Unsupervised Learning for Image Classification [111] | 2022 | This survey examines image classification, focusing on semi-supervised, self-supervised, and unsupervised learning methods to understand their effectiveness and potential applications. |

| A survey on semi-supervised learning for delayed partially labelled data streams [114] | 2022 | This study delves into semi-supervised learning approaches employed for handling delayed data streams with semi labels, focusing on their effectiveness and challenges. |

| Semi Supervised deep learning for image classification with distribution mismatch: A survey [115] | 2022 | This study explores Semi-Supervised Deep Learning for image classification with distribution mismatch, providing insights into its strategies and challenges. |

| A Survey on Deep Semi-supervised Learning [49] | 2023 | This survey examines the field of deep semi-supervised learning techniques, providing insights into their applications and advancements. |

| Graph-based semi-supervised learning: A comprehensive review [116] | 2023 | This comprehensive review examines the effectiveness and applications of graph-based semi-supervised learning methods. |

| Methods | Stages | Reference | COCO-Partial | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 5% | 10% | |||

| One Teacher [99] | One Stage | - | 15.4 | 36.70 | 45.3 |

| DSL [95] | CVPR22 | 22.03 | 30.87 | 36.22 | |

| Dense Teacher [96] | ECCV22 | 22.38 | 33.01 | 37.13 | |

| Unbiased Teacher v2 [98] | CVPR22 | 22.71 | 30.08 | 32.61 | |

| S4OD [97] | - | 23.70 | 32.30 | 35.00 | |

| Consistent-Teacher [94] | CVPR23 | 25.30 | 36.10 | 40.00 | |

| Rethinking pse [91] | Two Stage | AAAI22 | 9.02 | 28.40 | 32.23 |

| CSD [77] | ICML23 | 10.51 | 18.63 | 22.46 | |

| STAC [78] | - | 13.97 | 24.38 | 28.64 | |

| Humble Teacher [79] | CVPR22 | 16.96 | 27.70 | 31.61 | |

| Instant-Teaching [80] | CVPR21 | 18.05 | 26.75 | 30.40 | |

| ISMT [86] | CVPR21 | 18.41 | 26.37 | 30.53 | |

| Combating Noise [84] | - | 18.41 | 28.96 | 32.43 | |

| Soft Teacher [81] | ICCV21 | 20.46 | 30.74 | 34.04 | |

| Unbiased Teacher [82] | ICLR21 | 20.75 | 28.27 | 31.50 | |

| DTG-SSOD [90] | - | 21.27 | 31.90 | 35.92 | |

| MUM [85] | CVPR22 | 21.88 | 28.52 | 31.87 | |

| Active Teacher [92] | CVPR22 | 22.20 | 30.07 | 32.58 | |

| PseCo [76] | ECCV22 | 22.43 | 32.50 | 36.06 | |

| CrossRectify [87] | CVPR22 | 22.50 | 32.80 | 36.30 | |

| Label Match [89] | CVPR22 | 25.81 | 32.70 | 35.49 | |

| ACRST [83] | - | 26.07 | 31.35 | 34.92 | |

| SED [88] | CVPR22 | - | 29.01 | 34.02 | |

| SCMT [93] | IJCAI22 | 23.09 | 32.14 | 35.42 | |

| Omni-DETR [75] | End to End | CVPR22 | 27.60 | 37.70 | 41.30 |

| Semi-DETR [73] | CVPR23 | 30.50 | 40.10 | 43.5 | |

| Sparse Semi-DETR [74] | CVPR24 | 30.90 | 40.80 | 44.30 | |

| STEP DETR [176] | ICCV25 | 31.70 | 41.1 | 45.4 | |

| Methods | Stages | Reference | PASCAL-VOC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S4OD [97] | One Stage | - | 50.1 | - | 34.0 |

| Dense Teacher [96] | ECCV22 | 79.89 | 55.87 | - | |

| DSL [95] | CVPR22 | 80.7 | 56.8 | - | |

| Consistent-Teacher [94] | CVPR23 | 81.00 | 59.00 | - | |

| Unbiased Teacher v2 [98] | CVPR22 | 81.29 | 56.87 | - | |

| One Teacher [99] | - | 76.1 | - | - | |

| Soft Teacher [81] | Two Stage | ICCV21 | 20.46 | 30.74 | 34.04 |

| Combating Noise [84] | - | 43.2 | 62.0 | 47.5 | |

| DTG-SSOD [90] | - | 56.4 | - | 38.8 | |

| PseCo [76] | ECCV22 | 57.2 | - | 39.2 | |

| CSD [77] | ICML23 | 74.70 | - | - | |

| ISMT [86] | CVPR21 | 77.23 | 46.23 | - | |

| Unbiased Teacher [82] | ICLR21 | 77.37 | 48.69 | - | |

| STAC [78] | - | 77.45 | 44.64 | - | |

| ACRST [83] | - | 78.16 | 50.1 | - | |

| MUM [85] | CVPR22 | 78.94 | 50.22 | - | |

| Rethinking pse [91] | AAAI22 | 79.0 | 54.60 | 59.4 | |

| Instant-Teaching [80] | CVPR21 | 79.20 | 50.00 | 54.00 | |

| Humble Teacher [79] | CVPR22 | 80.94 | 53.04 | - | |

| CrossRectify [87] | CVPR22 | 82.34 | - | - | |

| Label Match [89] | CVPR22 | 85.48 | 55.11 | - | |

| SED [88] | CVPR22 | 80.60 | - | - | |

| Semi-DETR [73] | End to End | CVPR23 | 86.10 | 65.2 | - |

| Sparse Semi-DETR [74] | CVPR24 | 86.30 | 65.51 | - | |

| STEP DETR [176] | ICCV25 | 86.85 | 65.87 | - | |

| Methods | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Stac [78] | Improves detection performance with minimal complexity. | Low performance with frameworks employing intense hard negative mining, leading to over dependence on noisy pseudo-labels. |

| Humble Teacher [79] | Improves performance significantly with dynamic teacher model updates and soft pseudo-labels. | More computational resources due to the dynamic updating of the teacher model and the ensemble of numerous teacher models, potentially increasing training time and complexity. |

| Instant Teaching [80] | Improving model learning with extended weak-strong data augmentation as well as instant pseudo labeling. | Dependency on Extensive weak-strong data augmentation and instant pseudo labeling introduce computational overhead, increase training complexity and time. |

| Soft Teacher [81] | Enhances detector performance and pseudo label quality simultaneously. | Depending on extensive data augmentation and the soft teacher approach potentially increase training complexity and computational overhead. |

| Unbiased Teacher [82] | Effectively mitigates pseudo-labeling bias and overfitting in Semi-Supervised Object Detection. | Relies on the balance between the student and teacher models, which require careful tuning and additional computational resources. |

| ACRST [83] | Improves performance by addressing class imbalance. | Effectiveness relies on the precision of pseudo-labels, which are impacted by noise due to the complexity of detection tasks, requiring robust filtering mechanism. |

| Combating Noise [84] | Effectively combating noise associated with pseudo labels enhances the robustness of the SSOD Tasks. | Dependence on accurately quantifying region uncertainty is challenging in complex scenes or datasets with diverse object characteristics. |

| MUM [85] | Effectively augments data for Semi-Supervised Object Detection, enhancing model robustness without significant computational overhead. | Encounter difficulties in accurately locating object boundaries due to the mixing process, potentially affecting localization precision. |

| ISTM [86] | Effectively leveraging ensemble learning to enhance the usefulness of pseudo labels and stabilize Semi-Supervised Object Detection training. | Introduce additional computational complexity due to the ensemble approach and the use of multiple ROI heads, potentially increasing training time and resource requirements. |

| Cross Rectify [87] | Enhances pseudo label quality and detection performance by rectifying misclassified bounding boxes using detector disagreements. | Simultaneous training of two detectors increase computational overhead, potentially prolonging training time and resource usage. |

| SED [88] | Improves Semi-Supervised Object Detection by enforcing scale consistency and self-distillation. | Reliance on the IoU threshold criterion, which could not be optimal for all detectors and situations, and its limited benefits from multi-scale testing |

| Label Match [89] | Improves Semi-Supervised Object Detection by addressing label mismatch through distribution-level and instance-level methods. | Assumes Both unlabeled as well as labeled data have the same distribution, potentially restricting its applicability in diverse scenarios. |

| DTG-SSOD [90] | Leverages Dense Teacher Guidance for more accurate supervision, enhancing Semi-Supervised Object Detection performance. | Implementation complexity, especially with Inverse NMS Clustering and Rank Matching, increase computational resources during training. |

| Rethinking Pse [91] | Certainty-aware pseudo labels improve performance by addressing localization precision and class imbalance issues | Implementing certainty-aware pseudo labeling add additional computational complexity during training. |

| CSD [77] | Leverages consistency constraints for both classification and localization, enhancing object detection performance using unlabeled data. | It shows less performance improvement in two-stage detectors compared to single-stage detectors. |

| PseCo [76] | Enhances SSOD by integrating object detection attributes into pseudo labeling along with consistency training, leading to superior performance and faster convergence. | Its potential struggle with generalization across diverse datasets due to variability in pseudo-label quality. |

| Active Teacher [92] | Maximizes limited label information through active sampling, enhancing pseudo-label quality and improving SSOD performance. | Require more training steps compared to other methods, potentially increasing computational overhead. |

| One Teacher [99] | Improves SSOD on YOLOv5, tackling issues like low-quality pseudo-labeling. | Lowering the threshold for pseudo-labeling due to noisy pseudo-labeling in one-stage detection makes it difficult to maximize the effectiveness of one-stage teacher–student learning. |

| Dense Teacher [96] | Simplifies the SSOD pipeline by using Dense Pseudo-Labels, improving efficiency and performance. | Contain high-level noise, potentially impacting detection performance if not properly addressed. |

| Unbiased Teacher v2 [82] | Expands the applicability of SSOD to anchor-free detectors, improving performance across various benchmarks. | Challenges remain in scaling the method to large datasets, integrating localization uncertainty estimation for boundary prediction with the relative thresholding mechanism, and addressing domain shift issues. |

| S4OD [97] | Dynamically adjusts pseudo-label selection to balance quality and quantity, enhancing single-stage detector performance | DSAT strategy’s increased time cost is due to F1-score computation, and using the CPU version of NMS for uncertainty computation slows down training. |

| Consistent-Teacher [94] | Improves SSOD performance by addressing inconsistent pseudo-targets with feature alignment, adaptive anchor assignment, and dynamic threshold adjustment. | Performance is validated mainly on single-stage detectors, with effectiveness on stage-two detectors and DETR-based models yet to be confirmed. |

| Omni-DETR [75] | utilize diverse weak annotations to enhance performance and annotation efficiency. | Effectiveness on larger datasets is uncertain, and its simplified annotation process could raise concerns about potential misuse. |

| Semi-DETR [73] | Combines Cross-view query consistency and stage-wise hybrid matching to improve training efficiency. | Encounter challenges due to the absence of deterministic connection between the predictions and the input queries. |

| Sparse Semi-DETR [74] | Introduces a Query Refinement Module to improve object query functionality, enhancing detection performance for small and obscured objects. | Require additional computational resources due to the integration of novel modules, potentially increasing training time and complexity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shehzadi, T.; Ifza, I.; Liwicki, M.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Semi-Supervised Object Detection: A Survey on Progress from CNN to Transformer. Sensors 2026, 26, 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010310

Shehzadi T, Ifza I, Liwicki M, Stricker D, Afzal MZ. Semi-Supervised Object Detection: A Survey on Progress from CNN to Transformer. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):310. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010310

Chicago/Turabian StyleShehzadi, Tahira, Ifza Ifza, Marcus Liwicki, Didier Stricker, and Muhammad Zeshan Afzal. 2026. "Semi-Supervised Object Detection: A Survey on Progress from CNN to Transformer" Sensors 26, no. 1: 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010310

APA StyleShehzadi, T., Ifza, I., Liwicki, M., Stricker, D., & Afzal, M. Z. (2026). Semi-Supervised Object Detection: A Survey on Progress from CNN to Transformer. Sensors, 26(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010310