SharpCEEWPServer: A Lightweight Server for the Communication Protocol of China Earthquake Early Warning Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. CSTP Overview

- Session flow: Defines the complete sequence of events after a client and server establish a connection, including handshake, control command transmission, data transmission, and termination;

- Command format: Specifies control instructions during the session, excluding data, such as mode switching and parameter configuration.

- Data format: Defines how waveform and non-waveform data are encapsulated.

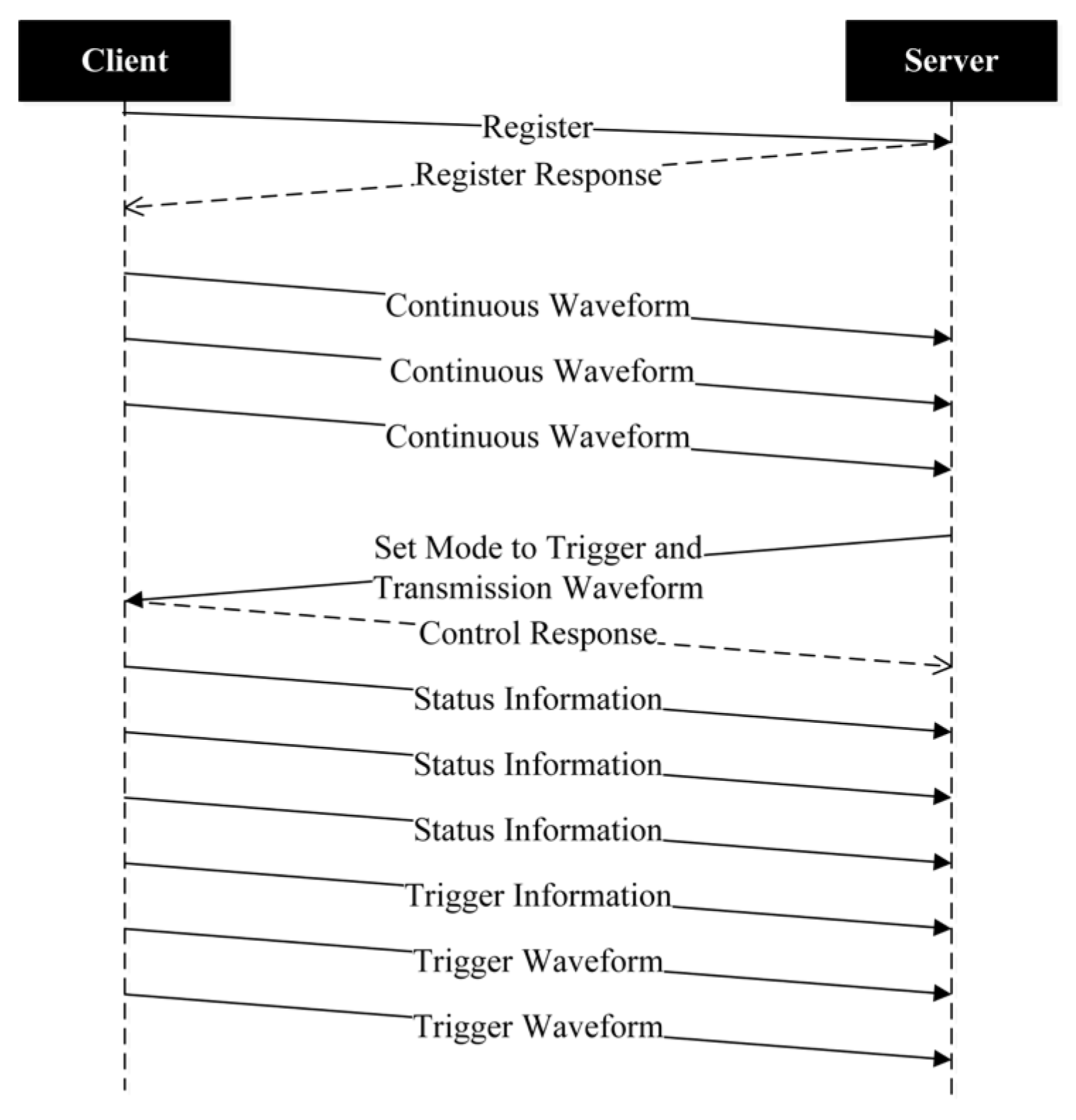

2.1. Session

2.2. Command

2.3. Data Format

- protocols that transmit custom data formats, such as CD-1 and Earthworm;

- protocols that are based on the SEED format and transmit MiniSEED packets, including LISS, SeedLink, NetSeis/IP, and DataLink [32].

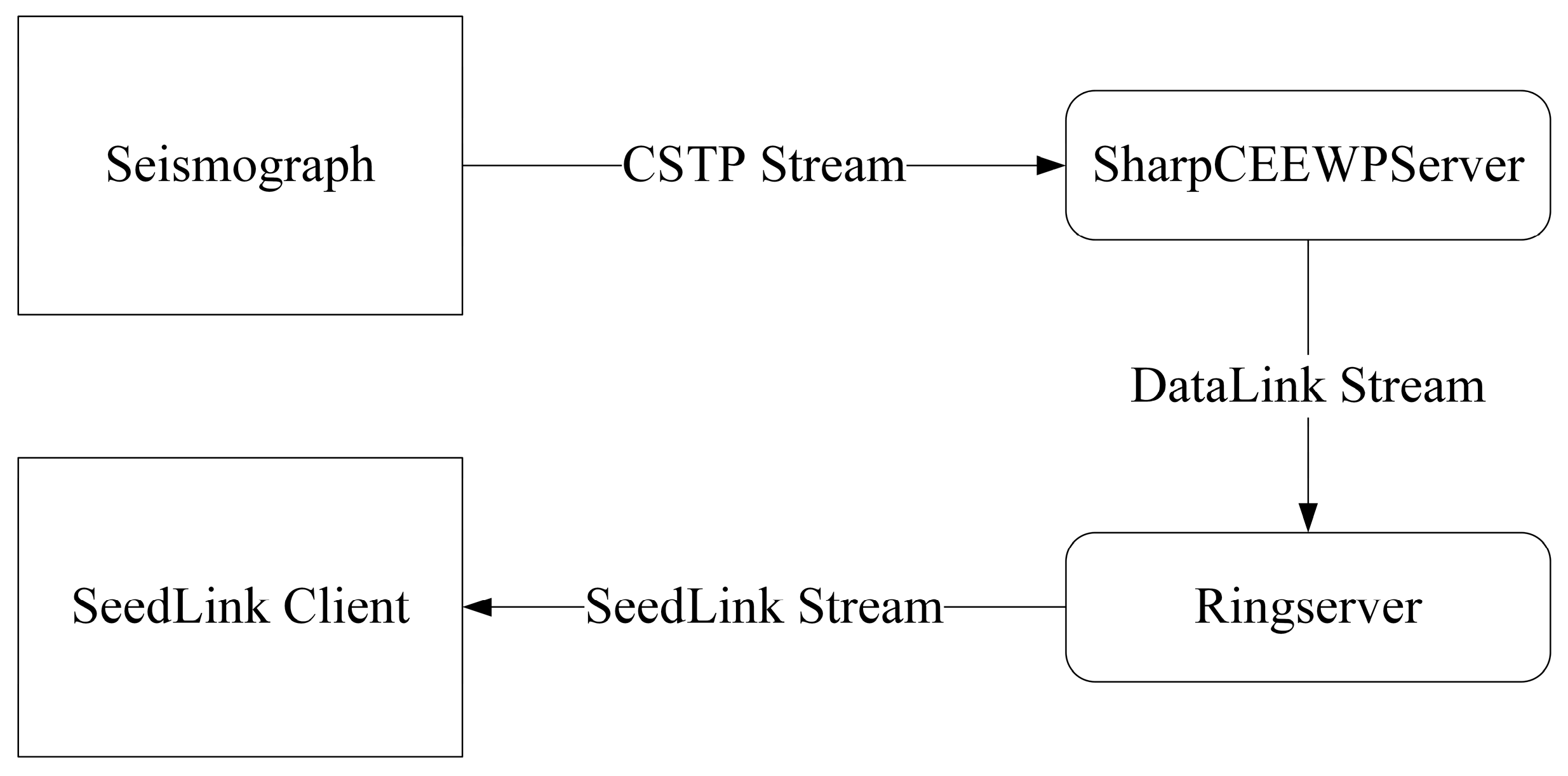

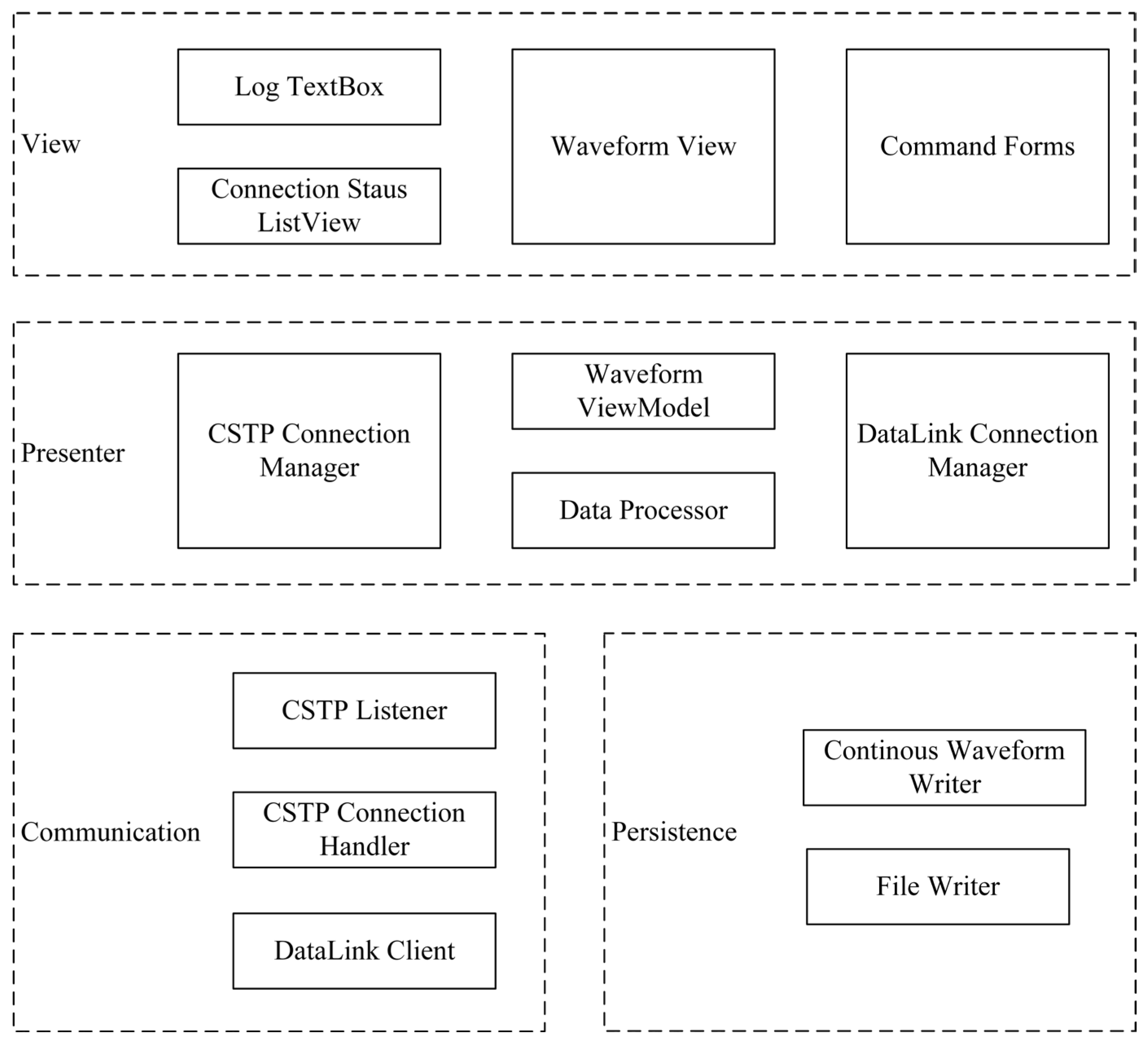

3. Design of Architecture

3.1. Communication and Persistence Layer

3.2. Presenter Layer

3.3. View Layer

4. Implementation

5. Tests

5.1. Hardware Compatibility Tests

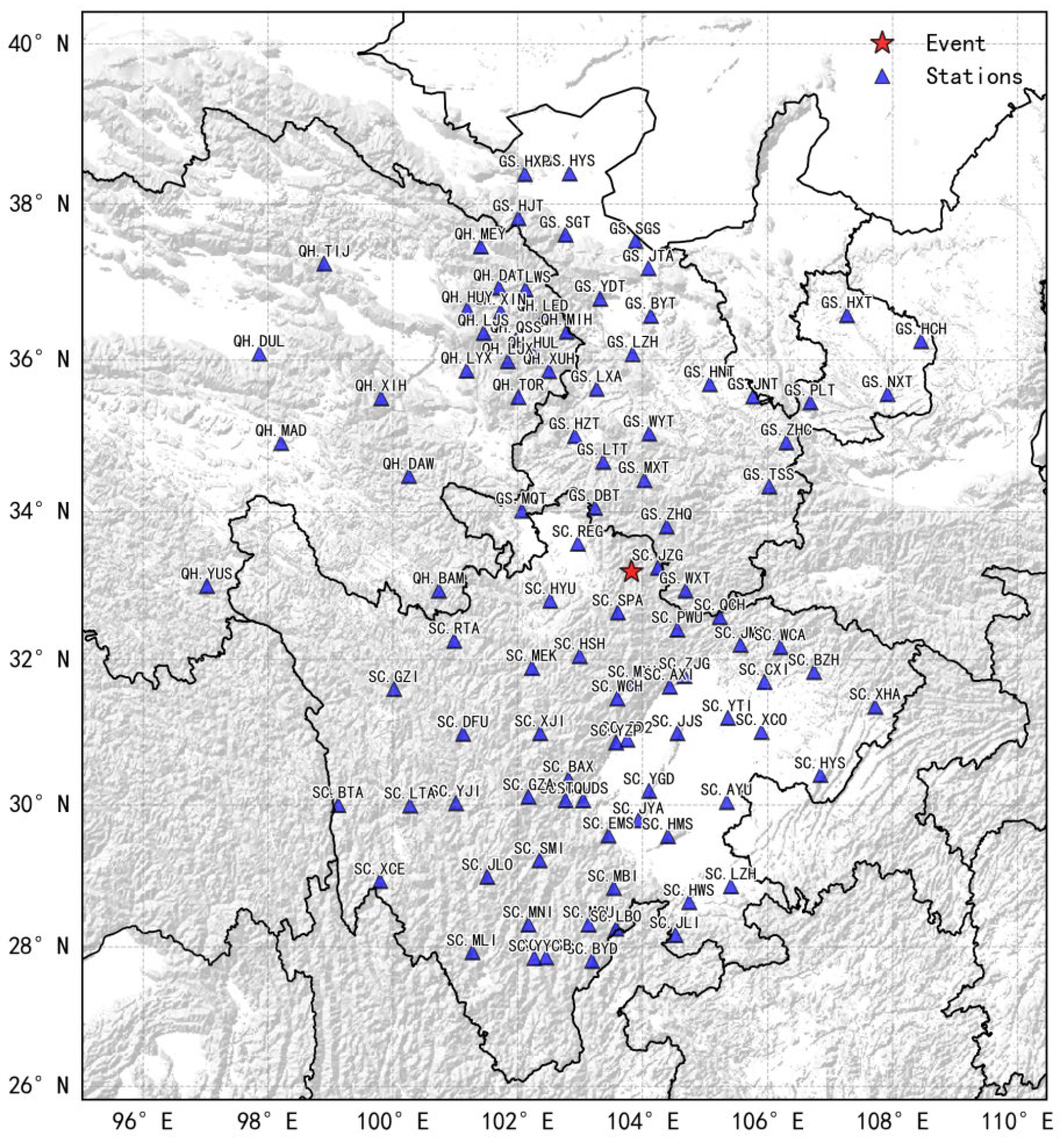

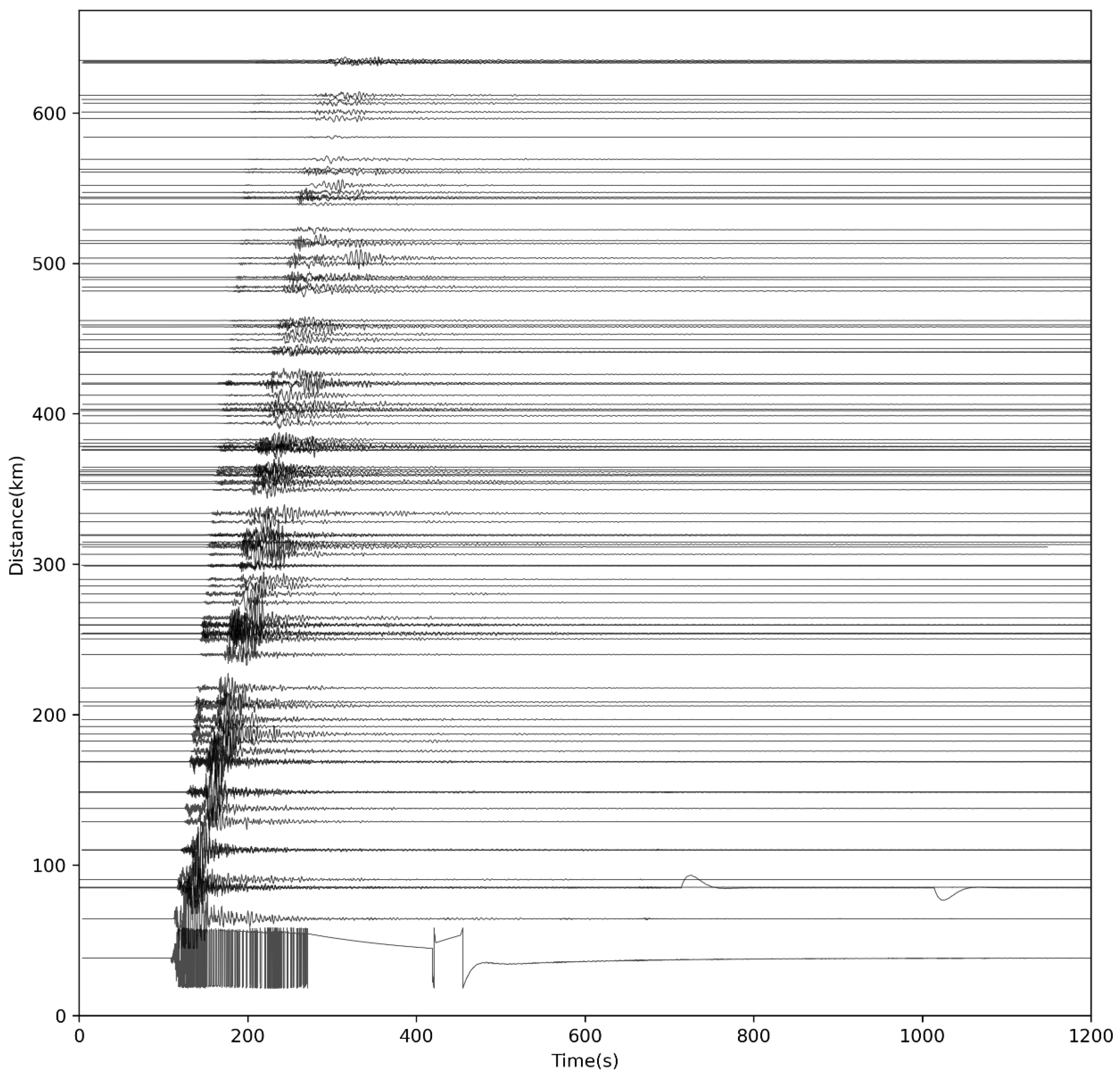

5.2. Real-Time Data Stream Forwarding Tests

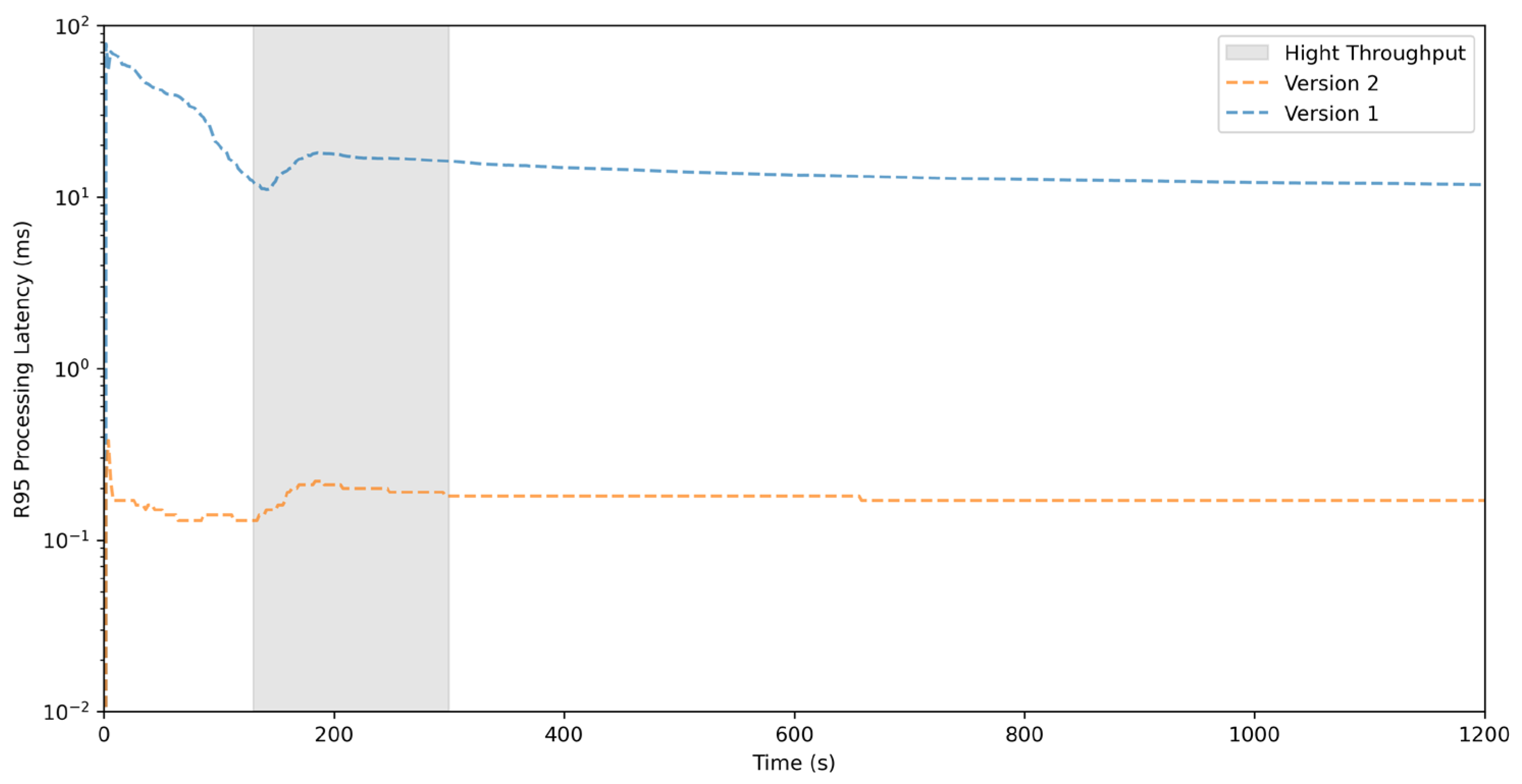

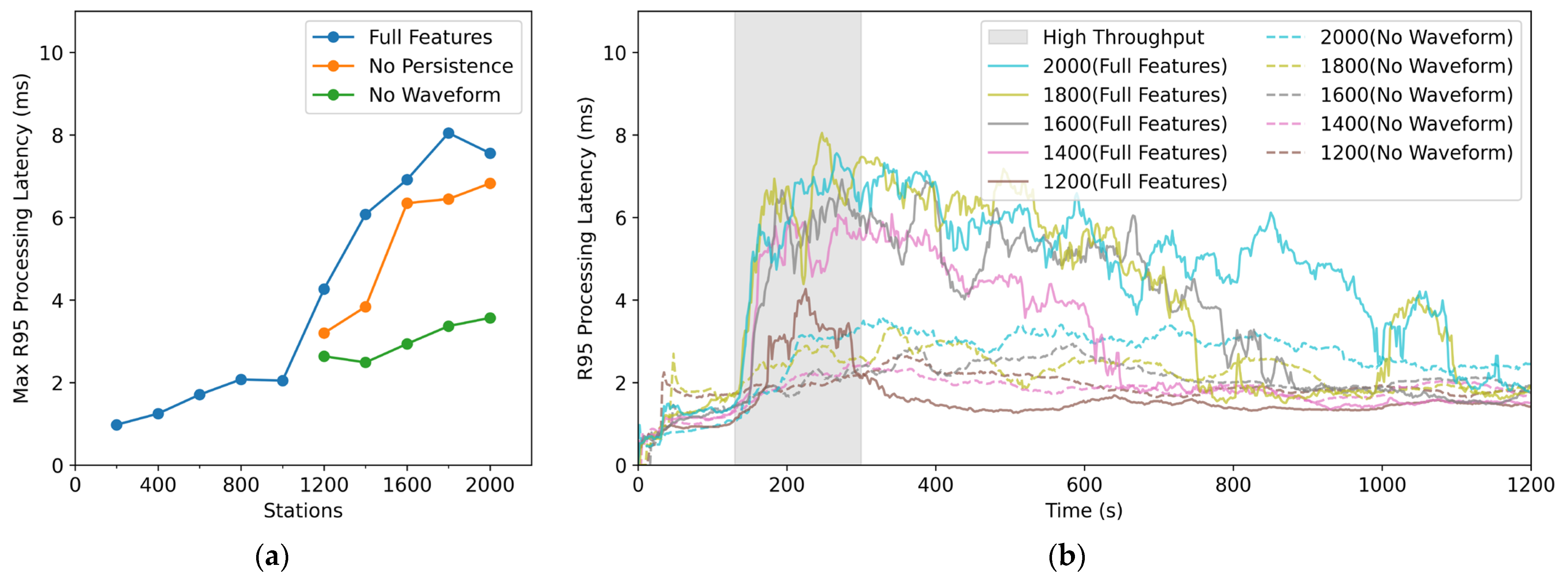

5.3. Concurrency Performance Tests

5.4. Network Impairment Testing

5.5. CSTP to SeedLink Conversion Performance Test

6. Conclusions and Discussion, Limitations, and Future Work

- Software Test Results Analysis

- (1)

- Hardware Compatibility and Data Reliability

- (2)

- Concurrency Performance Limits

- (3)

- Network Robustness and Forwarding Latency

- 2.

- Software Application Value and Future Plans

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LISS | Live Internet Seismic Server |

| CEA | China Earthquake Administration |

| EEW | Earthquake early warning |

| EEWS | Earthquake early warning system |

| FIFO | first-in–first-out |

References

- Li, D.; Han, L.; Huang, W. The Application Imagine of LISS System in China Digital Seismic Network. Seismol. Geomagn. Obs. Res. 2001, 23, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Havskov, J.; Ottemöller, L.; Trnkoczy, A.; Bormann, P. Seismic Networks. In New Manual of Seismological Observatory Practice 2 (NMSOP-2); Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum GFZ: Potsdam, Germany, 2012; 65p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seedlink—SeisComP Release Documentation. Available online: https://www.seiscomp.de/doc/apps/seedlink.html#seedlink-sources-liss-label (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Berger, J.; Bowman, R.; Burns, J.; Chavez, D.; Cordova, R.; Coyne, J.; Farrell, W.E.; Firbas, P.; Fox, W.; Given, J.; et al. Formats and Protocols for Continuous Data CD-1.1; Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC): Reston, VA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Earthworm Wave Server Protocol. Available online: http://www.earthwormcentral.com/documentation4/PROGRAMMER/wsv_protocol.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Libdali: DataLink Protocol. Available online: https://earthscope.github.io/libdali/datalink-protocol.html (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- China Seismographic Network Data Specification. Available online: https://www.doc88.com/p-0572881541234.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Guangdong Earthquake Monitoring Center. Data Processing System for the Digital Seismic Network Center JOPEN5; Guangdong Earthquake Administration: Guangzhou, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Doi, K. The Operation and Performance of Earthquake Early Warnings by the Japan Meteorological Agency. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 31, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.M.; Allen, R.M.; Hellweg, M.; Khainovski, O.; Neuhauser, D.; Souf, A. Development of the ElarmS Methodology for Earthquake Early Warning: Realtime Application in California and Offline Testing in Japan. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 31, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, M.; Hauksson, E.; Solanki, K.; Kanamori, H.; Wu, Y.-M.; Heaton, T.H. A New Trigger Criterion for Improved Real-Time Performance of Onsite Earthquake Early Warning in Southern California. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2009, 99, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.I.; Henson, I.; Allen, R.M. Optimizing Earthquake Early Warning Performance: ElarmS-3. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2019, 90, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladina, C.; Marzorati, S.; Amato, A.; Cattaneo, M. Feasibility Study of an Earthquake Early Warning System in Eastern Central Italy. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 685751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, G.; Picozzi, M.; Caruso, A.; Colombelli, S.; Cattaneo, M.; Chiaraluce, L.; Elia, L.; Martino, C.; Marzorati, S.; Supino, M.; et al. Performance of Earthquake Early Warning Systems during the 2016–2017 Mw 5–6.5 Central Italy Sequence. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2018, 89, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdik, M.; Fahjan, Y.; Ozel, O.; Alcik, H.; Mert, A.; Gul, M. Istanbul Earthquake Rapid Response and the Early Warning System. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2003, 1, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wu, Z.; Wu, Y.-M.; Yu, S.; Zhang, D.; Huang, W. Developing a Prototype Earthquake Early Warning System in the Beijing Capital Region. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2011, 82, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhu, X.; Yang, J.; Xue, B.; Chen, Y. Development of an Integrated Onsite Earthquake Early Warning System and Test Deployment in Zhaotong, China. Comput. Geosci. 2013, 56, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Jiang, P.; Chen, Q.; Ma, Q.; Yang, J. Performance Evaluation of a Dense MEMS-Based Seismic Sensor Array Deployed in the Sichuan-Yunnan Border Region for Earthquake Early Warning. Micromachines 2019, 10, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Ma, Q.; Jiang, P.; Huang, W.; Yang, D.; Peng, H.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. Performance of a Hybrid Demonstration Earthquake Early Warning System in the Sichuan–Yunnan Border Region. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2020, 91, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Palma, L.; Belli, A.; Sabbatini, L.; Pierleoni, P. Recent Advances in Internet of Things Solutions for Early Warning Systems: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Belli, A.; Falaschetti, L.; Palma, L.; Pierleoni, P. An AIoT System for Earthquake Early Warning on Resource Constrained Devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 15101–15113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-M.; Chen, D.-Y.; Lin, T.-L.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Chin, T.-L.; Chang, W.-Y.; Li, W.-S.; Ker, S.-H. A High-Density Seismic Network for Earthquake Early Warning in Taiwan Based on Low Cost Sensors. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2013, 84, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liang, W.; Mittal, H.; Chao, W.; Lin, C.; Huang, B.; Lin, C. Performance of a Low-Cost Earthquake Early Warning System (P -Alert) during the 2016 ML 6.4 Meinong (Taiwan) Earthquake. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2016, 87, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierleoni, P.; Concetti, R.; Belli, A.; Palma, L.; Marzorati, S.; Esposito, M. A Cloud-IoT Architecture for Latency-Aware Localization in Earthquake Early Warning. Sensors 2023, 23, 8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierleoni, P.; Concetti, R.; Marzorati, S.; Belli, A.; Palma, L. Internet of Things for Earthquake Early Warning Systems: A Performance Comparison Between Communication Protocols. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 43183–43194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wu, Y.; Wu, S.; Su, Z.; Ouyang, L. About Data Transmission Protocol on Seismic Intensity Instrument. Seismol. Geomagn. Obs. Res. 2017, 38, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangdong Earthquake Monitoring Center. Data Processing System for the Digital Seismic Network Center JOPEN6; Guangdong Earthquake Administration: Guangzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, X.; Wei, Y.; Li, J.; Kang, L.; Wang, S.; Huang, L.; Yu, P. An Earthquake Early Warning System in Fujian, China. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2016, 106, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Jiang, P.; Ma, Q.; Su, J.; Cai, Y.; Zheng, Y. Chinese Nationwide Earthquake Early Warning System and Its Performance in the 2022 Lushan M6.1 Earthquake. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, Y. A New Type of Tri-Axial Accelerometers with High Dynamic Range MEMS for Earthquake Early Warning. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 100, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabant, C. Ringserver—Streaming Data Server 2020. Available online: https://github.com/EarthScope/ringserver (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks. Standard for the Exchange of Earthquake Data; Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS): New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Trabant, C. Slinktool 2023. Available online: https://github.com/EarthScope/slinktool (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Anandakrishnan, S. Steim Compression. In Propeller Programming; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 17–23. ISBN 978-1-4842-3353-5. [Google Scholar]

- Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS). Transportable Array USArray Transportable Array 2003. Available online: https://www.fdsn.org/networks/detail/TA/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Zeng, S.; Zheng, Y.; Niu, F.; Ai, S. Measurements of Seismometer Orientation of the First Phase CHINArray and Their Implications on Vector-Recording-Based Seismic Studies. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2021, 111, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Guo, Z.; Luo, B.; Qin, L.; Wu, C.; Wei, Z.; Ren, P.; Yu, H. Sensor Misorientation of CHINArray-II in Northeastern Tibetan Plateau from P- and Rayleigh-Wave Polarization Analysis. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2024, 95, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature/Model | Registration | CW 1 | TW 2 | TNW 3 | RC 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDE-324FI | Y | Y | Y | Y | P |

| GL-P2B | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| GL-PCS120 | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| HG-D6 | Y | Y | N | N | D |

| Metric | Normal | 100 ms Latency 5% Packet Loss 10% Out-of-Order | 10 Temporary Disconnections (Each ≥ 3 s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Packets Sent | 1425 | 1425 | 1425 |

| Packets Received | 1425 | 1425 | 1387 |

| Integrity Rate (%) | 100 | 100 | 97.3 |

| R95 Network Latency (ms) | 110.76 | 651.91 | 114.06 |

| R95 Processing Latency (ms) | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.33 |

| R95 End-to-End Latency (ms) | 110.98 | 652.14 | 114.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Li, J.; Xiang, W.; Liu, Z.; Liao, W.; Zhang, L. SharpCEEWPServer: A Lightweight Server for the Communication Protocol of China Earthquake Early Warning Systems. Sensors 2026, 26, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010262

Li L, Li J, Xiang W, Liu Z, Liao W, Zhang L. SharpCEEWPServer: A Lightweight Server for the Communication Protocol of China Earthquake Early Warning Systems. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010262

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Li, Jinggang Li, Wei Xiang, Zhumei Liu, Wulin Liao, and Lifen Zhang. 2026. "SharpCEEWPServer: A Lightweight Server for the Communication Protocol of China Earthquake Early Warning Systems" Sensors 26, no. 1: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010262

APA StyleLi, L., Li, J., Xiang, W., Liu, Z., Liao, W., & Zhang, L. (2026). SharpCEEWPServer: A Lightweight Server for the Communication Protocol of China Earthquake Early Warning Systems. Sensors, 26(1), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010262