Highly Sensitive Measurement of the Refractive Index of Mesoporous Hollow Silica Microcapsules Using Whispering Gallery Mode Resonances

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

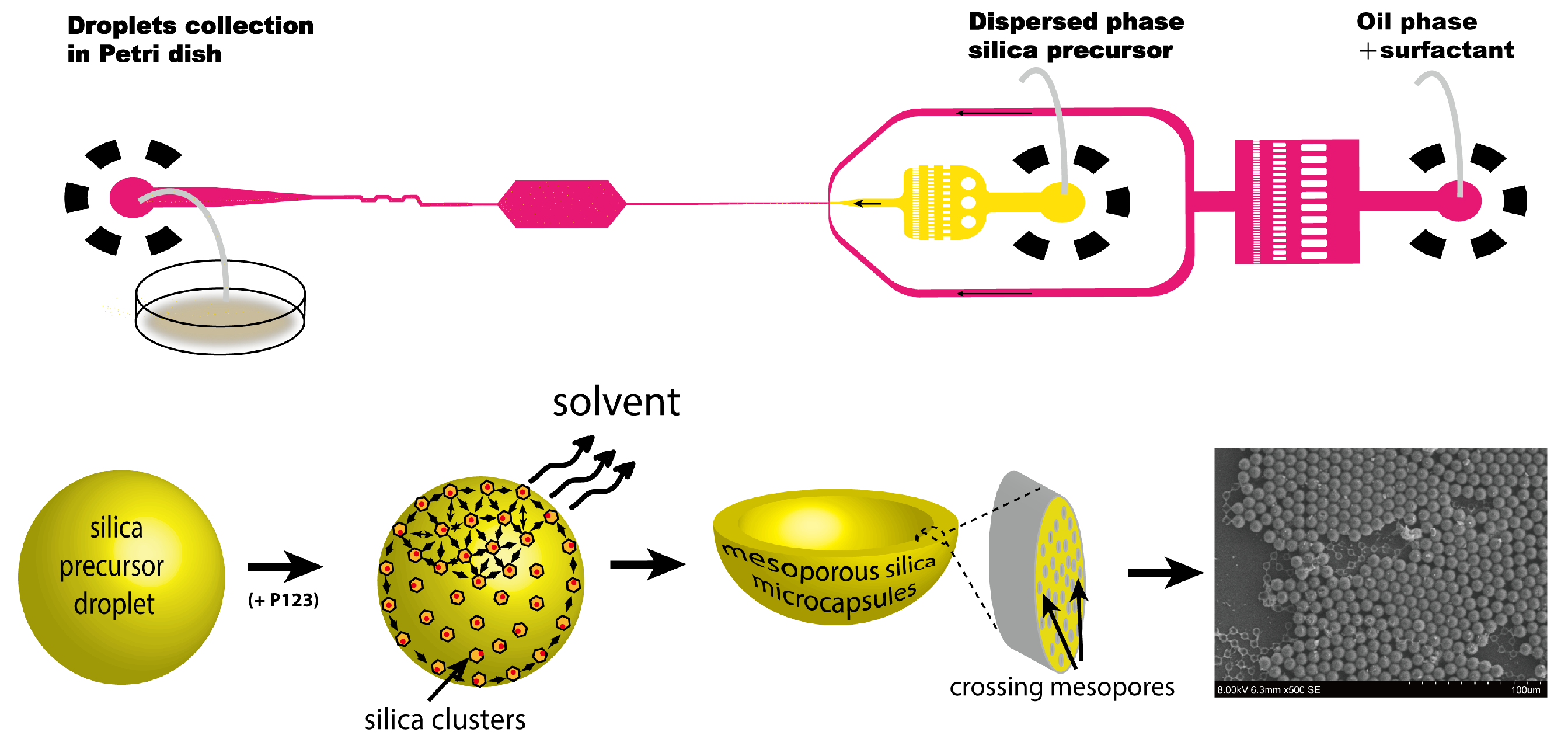

2.1. Microcapsules Fabrication Procedure

- In situ doping, in which Rhodamine B was directly added to the sol–gel precursor prior to droplet formation. While this approach allowed for dye entrapment during silica shell formation, it occasionally led to fluorescence self-quenching and a non-uniform spatial distribution due to uncontrolled encapsulation kinetics.

- Post-synthesis adsorption, where fully dried capsules were immersed in a 10 M aqueous Rhodamine B solution for 24–48 h. In this method, dye molecules gradually diffused into the mesoporous framework and adsorbed onto the internal pore walls via electrostatic and van der Waals interactions. After loading, the capsules were rinsed thoroughly under vacuum to remove unbound dye.

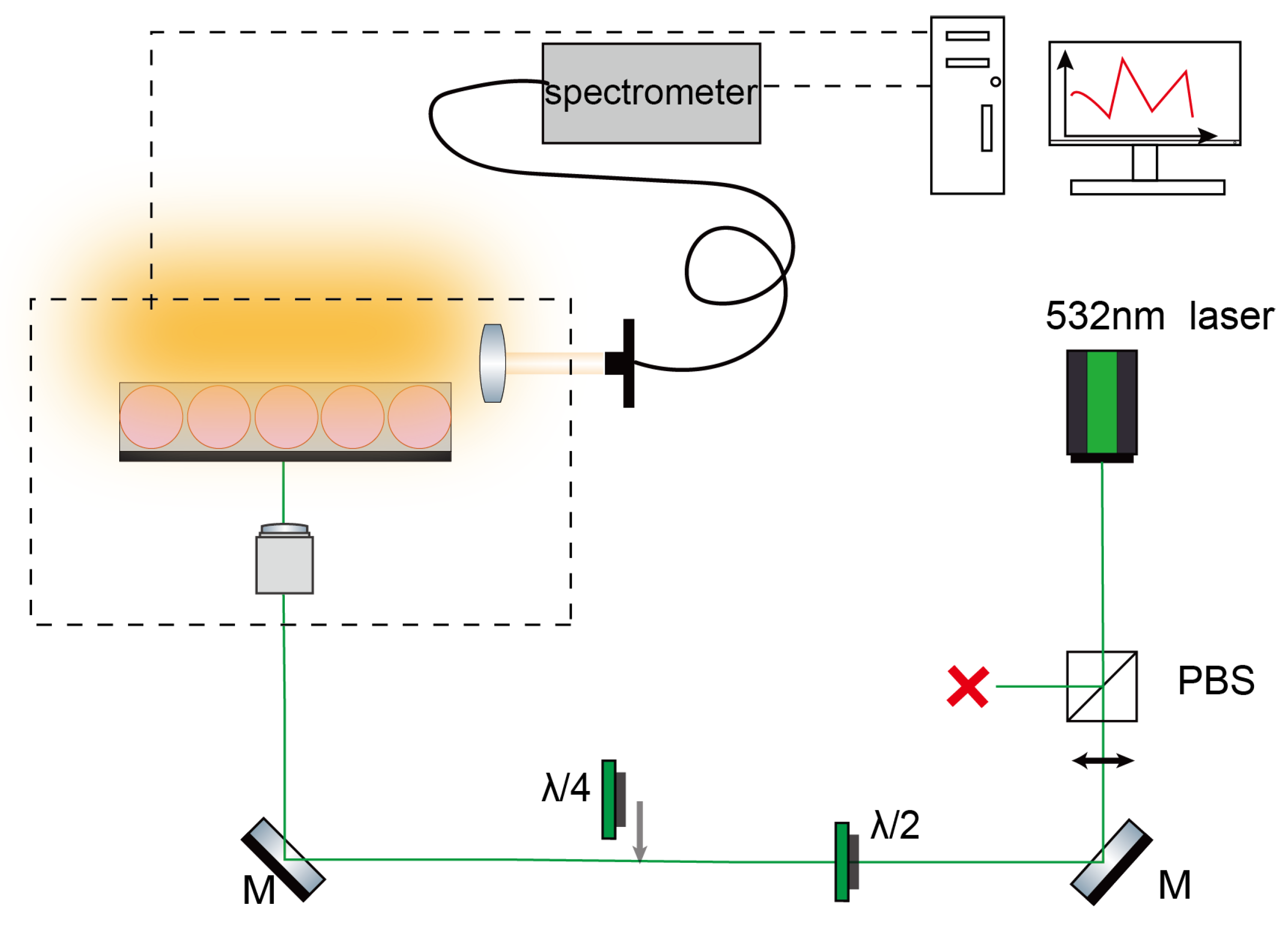

2.2. Optical Characterization and Refractive Index Measurement

2.3. Porosity Characterization via BET Nitrogen Adsorption

3. Results and Discussion

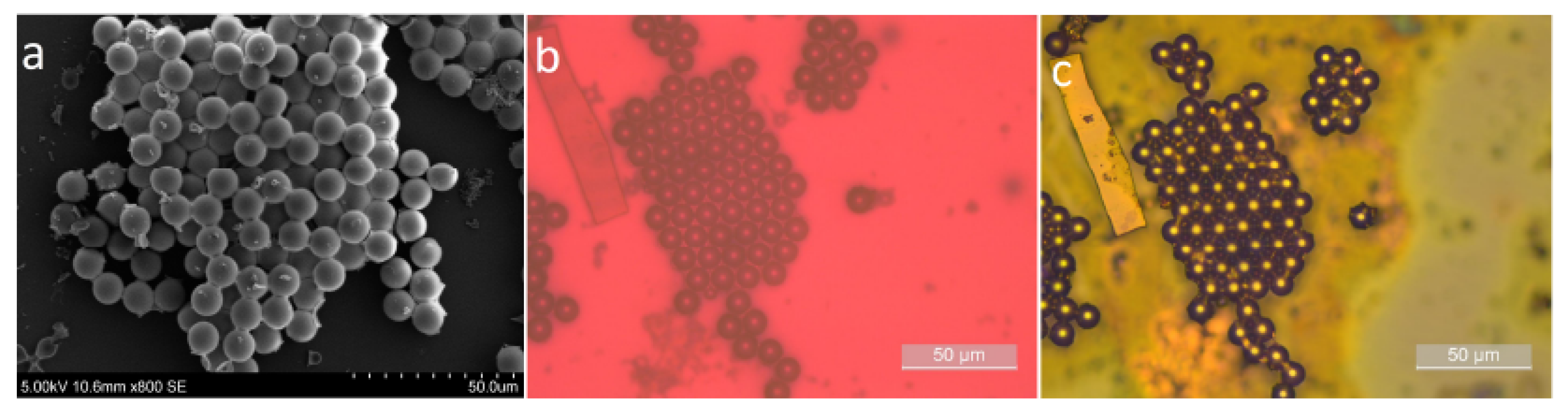

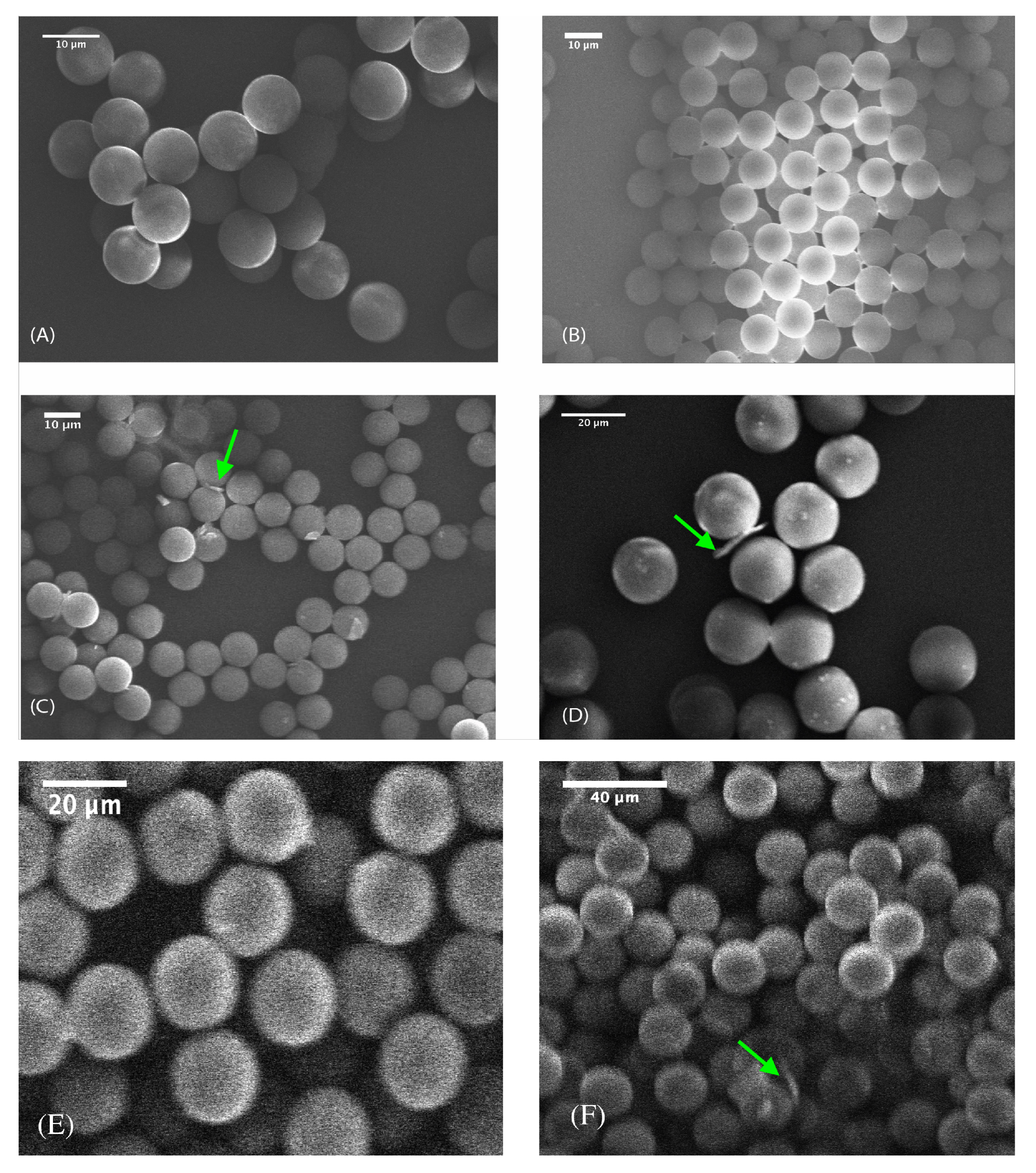

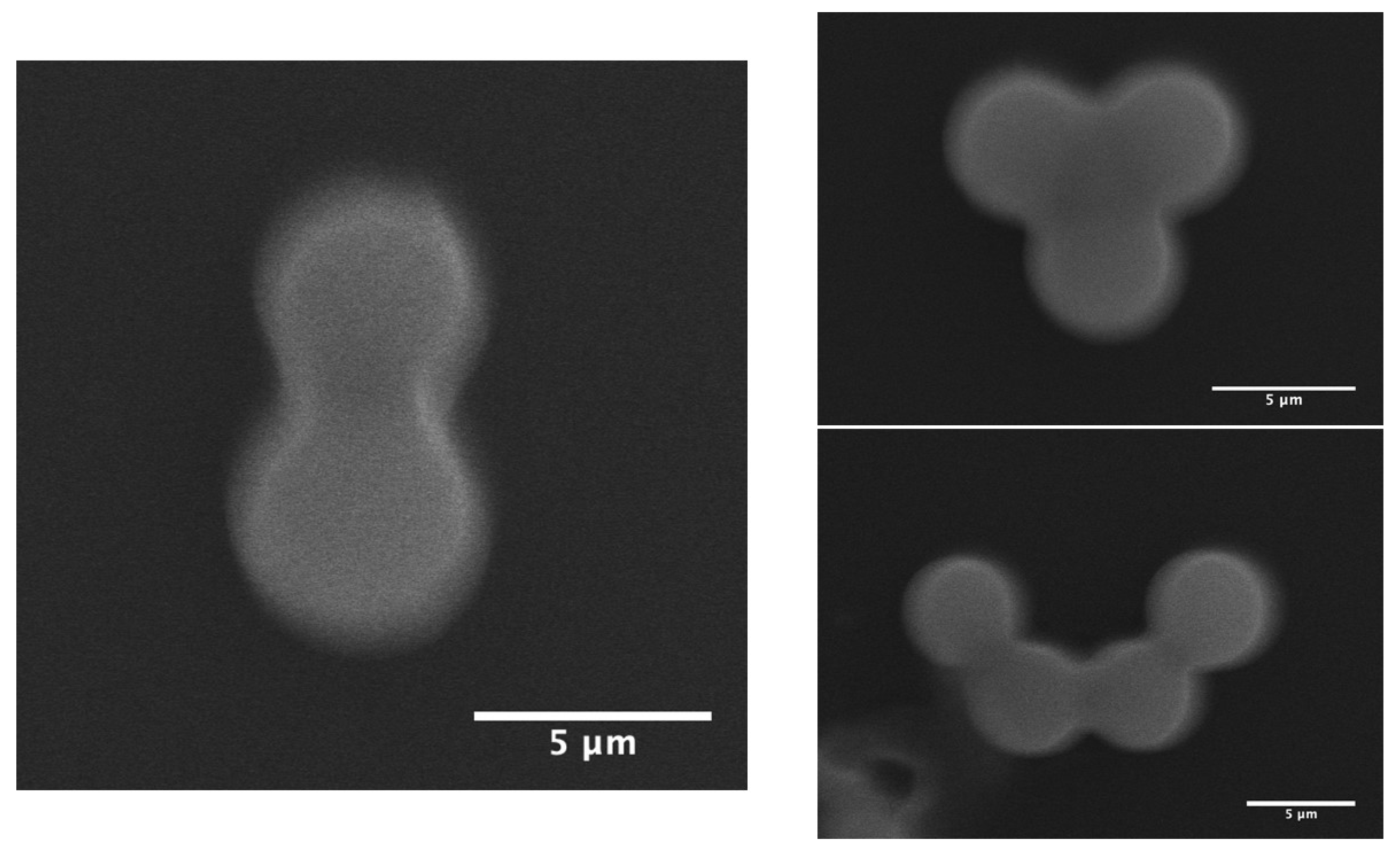

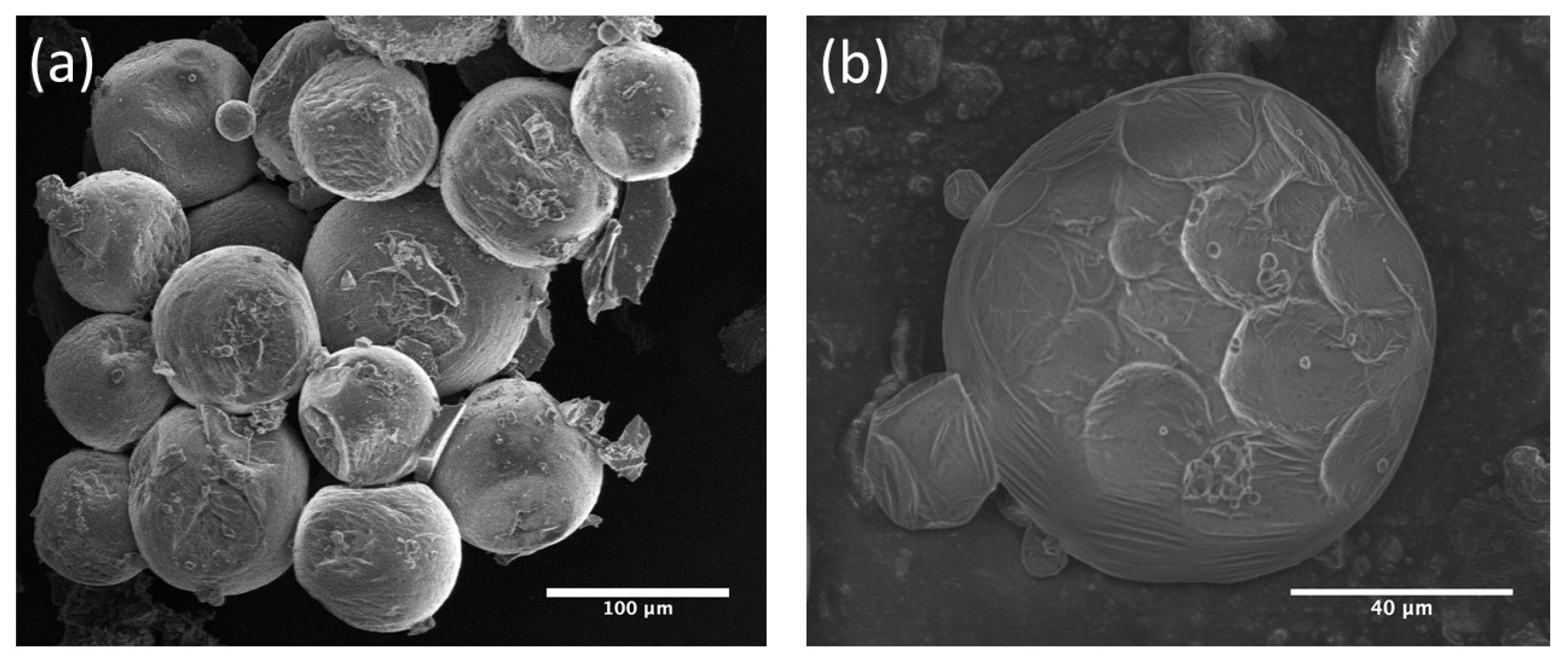

3.1. Microfluidic Synthesis of Mesoporous Hollow Silica Microcapsules with Different Sizes

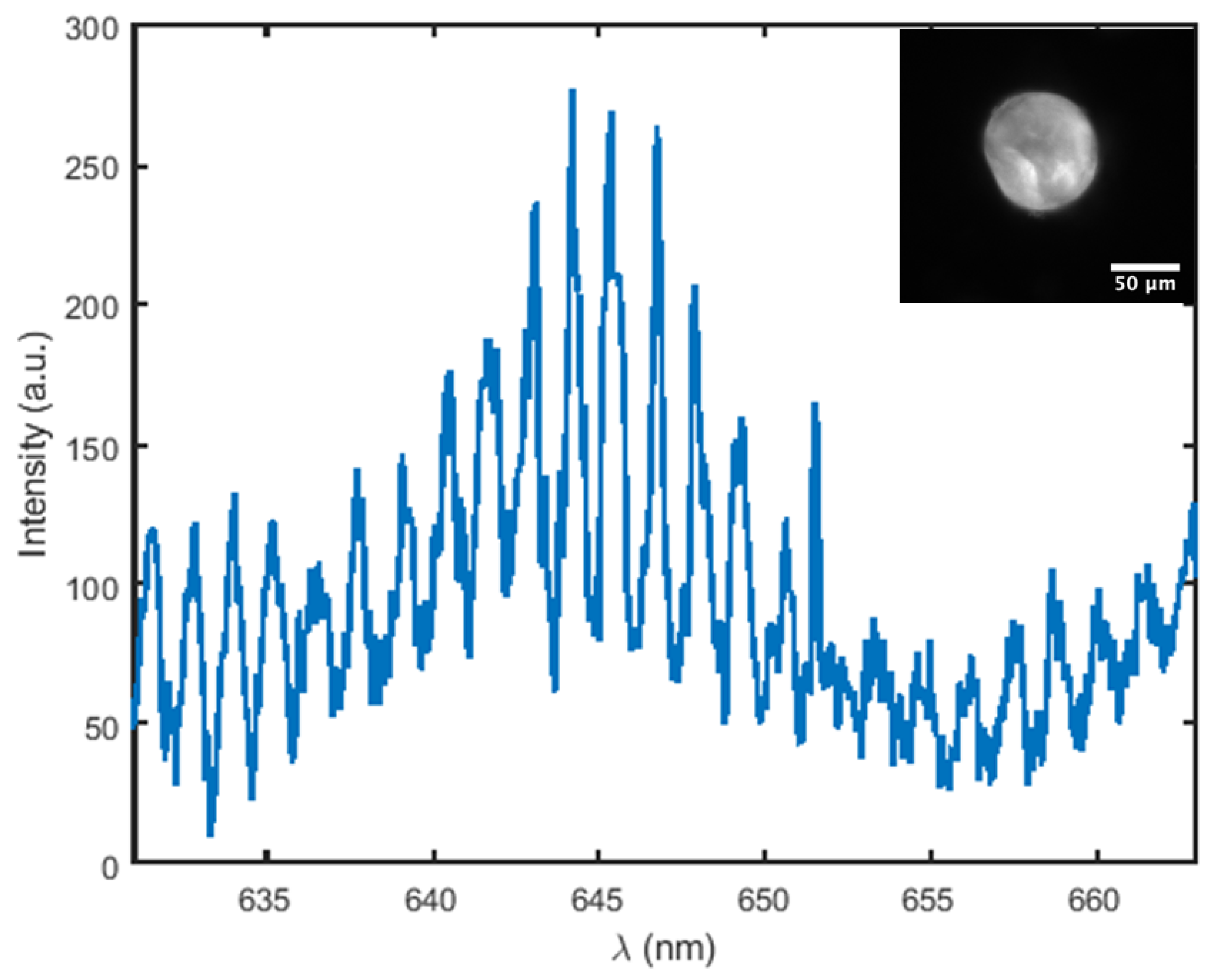

3.2. Observation of Whispering Gallery Modes in Mesoporous Hollow Silica Capsules

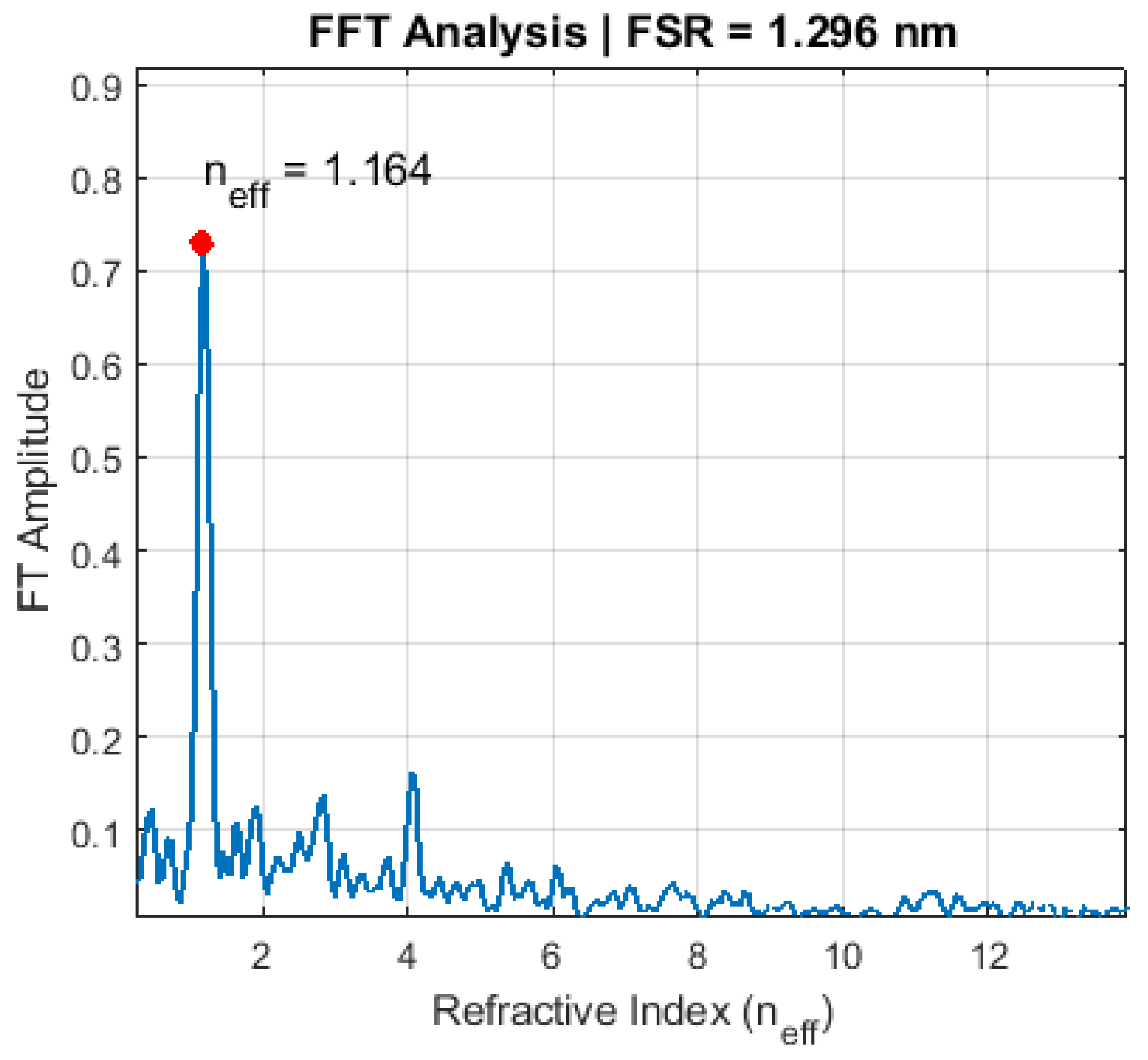

3.3. Refractive Index Extraction via Fourier Transform Analysis

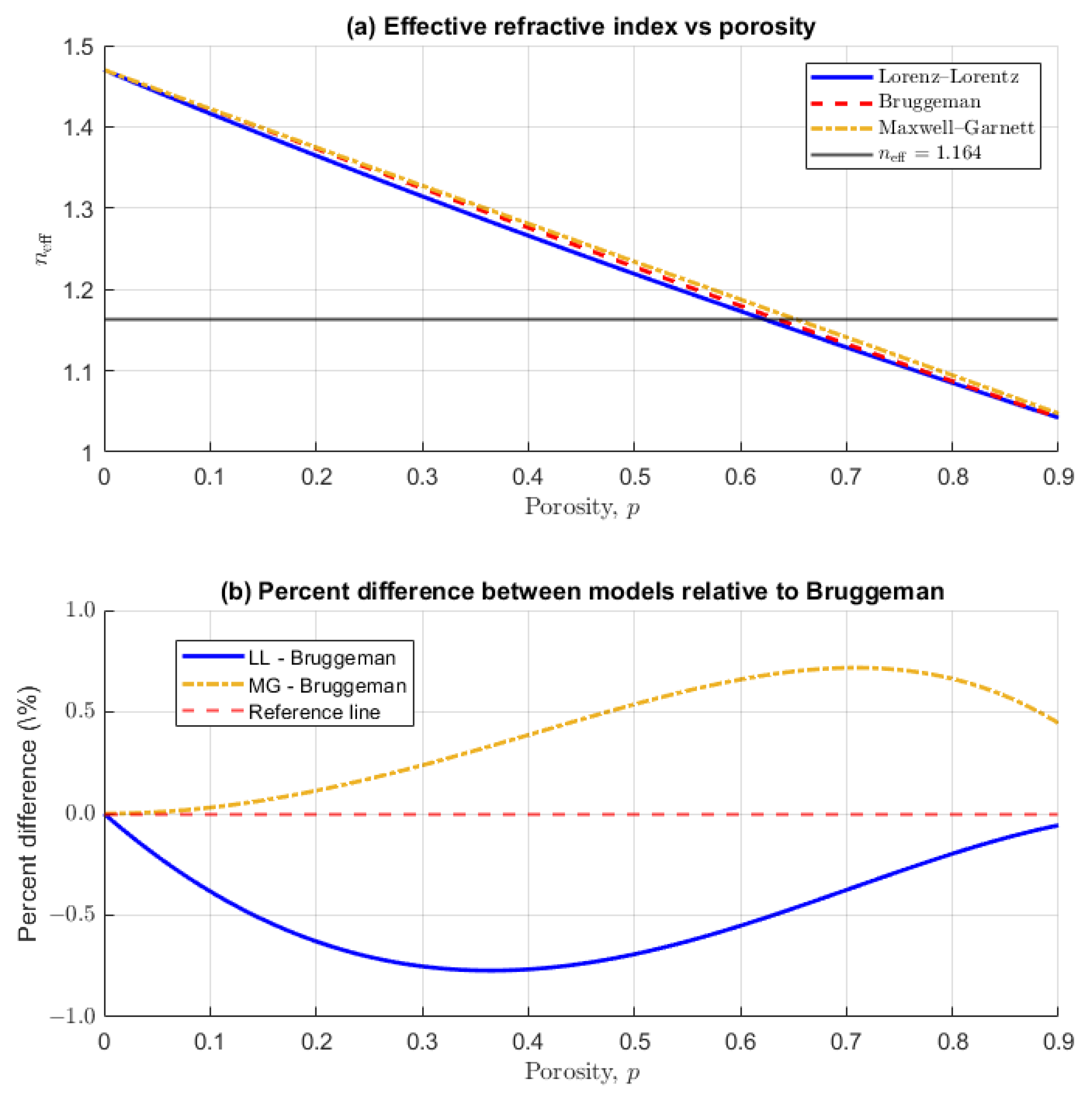

3.4. Porosity Determination via Effective Medium Models

- Single-particle sensitivity: WGM spectroscopy accurately captures the effective optical porosity of individual microcapsules, avoiding ensemble averaging inherent to bulk techniques.

- Pore connectivity: The superior performance of Bruggeman over Maxwell–Garnett corroborates the interconnected nature of the mesoporous network, consistent with type H1 hysteresis observed in adsorption isotherms for P123-templated materials.

- Architectural confirmation: The high porosity (∼63%) quantitatively validates the hollow-core, radially ordered mesoporous shell architecture achieved via microfluidic synthesis.

3.5. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soler-Illia, G.J.d.A.; Sanchez, C.; Lebeau, B.; Patarin, J. Chemical strategies to design textured materials: From microporous and mesoporous oxides to nanonetworks and hierarchical structures. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4093–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet-Regi, M.; Rámila, A.; del Real, R.P.; Pérez-Pariente, J. A novel mesoporous material for drug delivery. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slowing, I.I.; Vivero-Escoto, J.L.; Wu, C.; Lin, V.S.Y. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery and biosensing applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, S.; Chen, T.; Ducheyne, P. The controlled release of drugs from emulsified, sol gel processed silica microspheres. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Shi, J.; Shen, W.; Dong, X.; Feng, J.; Ruan, M.; Li, Y. Stimuli-Responsive Controlled Drug Release from a Hollow Mesoporous Silica Sphere/Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Core–Shell Structure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5083–5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, D.E.; Dams, M.; Sels, B.F.; Jacobs, P.A. Ordered mesoporous and microporous molecular sieves functionalized with transition metal complexes as catalysts for selective organic transformations. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 3615–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Li, L.; Chen, D. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Biocompatibility and Drug Delivery. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1504–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarn, D.; Ashley, C.E.; Xue, M.; Carnes, E.C.; Zink, J.I.; Brinker, C.J. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle nanocarriers: Biofunctionality and biocompatibility. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, S.; Shahid, M.; Ashiq, M.N.; Iqbal, S.; Ali, A.; Ilyas, M. Mesoporous Materials: Synthesis and electrochemical energy applications. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 53, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocarlan, R.G.; Blomqvist, H.; Mouzon, J.; Lacroix, M.; Nieuwland, S.; Welter, E.; Jonsson, P.G.; Karlsson, H. Tuneable mesoporous silica material for hydrogen storage applications. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, S.E.; Hernández-Montoto, A.; Delgado, D.; Izquierdo-Barba, I.; Vallet-Regí, M. Degradation of Mesoporous Silica Materials in Biological Environments: Toward an Improved Design for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Nanobiomed Res. 2024, 4, 2400005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Li, S.; Shi, R.; Liu, H. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bchellaoui, N.; Hayat, Z.; Mami, M.; Dorbez-Sridi, R.; El Abed, A.I. Microfluidic-assisted formation of highly monodisperse and mesoporous silica soft microcapsules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Li, Y.; Duan, G.; Jia, L.; Cai, W. Microfluidic-assisted sol–gel preparation of monodisperse mesoporous silica microspheres with controlled size, surface morphology, porosity and stiffness. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 3421–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Hou, S.; Tang, Q.; Duan, M.; Fang, S. Synthesis of dendritic mesoporous silica nanoparticles by ultrasonic-assisted microchannel continuous flow reaction. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 17230–17240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Ishi, M.; Yano, K. Reversible control of light reflection of a colloidal crystal film fabricated from monodisperse mesoporous silica spheres. Langmuir 2006, 22, 2444–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, K.M.Z.; Patel, U.; Ahmed, I. Development of microspheres for biomedical applications: A review. Prog. Biomater. 2015, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; He, J. Spherical silica micro/nanomaterials with hierarchical structures: Synthesis and applications. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 3984–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Pan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, S. Whispering Gallery Mode Optical Microresonators: Structures and Sensing Applications. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2020, 217, 1900825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yang, L. Optothermal dynamics in whispering-gallery microresonators. Light Sci. Appl. 2020, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahala, K.J. Optical microcavities. Nature 2003, 424, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, F.; Arnold, S. Whispering-gallery-mode biosensing: Label-free detection down to single molecules. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Fan, H. Silica microdisk-based plasmonic whispering-gallery modes for refractive index and temperature sensing. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2025, 42, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zossimova, E.; Jones, C.; Perera, K.M.K.; Pedireddy, S.; Walter, M.; Vollmer, F. Whispering gallery mode sensing through the lens of quantum optics, artificial intelligence, and nanoscale catalysis. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, K.; Beeram, R.; Cao, Y.; dos Santos, P.S.S.; González-Cabaleiro, L.; García-Lojo, D.; Guo, H.; Joung, Y.; Kothadiya, S.; Lafuente, M.; et al. Plasmonic nanoparticle sensors: Current progress, challenges, and future prospects. Nanoscale Horiz. 2024, 9, 2085–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Z.; Wilkinson, J.S.; Zhou, X. Optical biosensors based on refractometric sensing schemes: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 144, 111693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, B.; Wang, W.; Wang, H. Determining the Local Refractive Index of Single Particles by Optical Imaging Technique. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 16085–16093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T. An effective medium approach to modelling the pressure-dependent electrical properties of porous rocks. Geophys. J. Int. 2018, 214, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.; Berg, P. Pore-network models and effective medium theory: A convergence analysis. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.07599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Schlumberger, C. Characterization of Nanoporous Materials. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2021, 12, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarian, B.; Daigle, H. Thermal conductivity in porous media: Percolation-based effective-medium approximation. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H. A novel effective medium theory for modelling the thermal conductivity of porous materials. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 68, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, H.; Weidenthaler, C. A review of recent developments for the in situ/operando characterization of nanoporous materials. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 4244–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bchellaoui, N.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Bendeif, E.E.; Bennacer, R.; El Abed, A.I. Role and effect of meso-structuring surfactants on properties and formation mechanism of microfluidic-enabled mesoporous silica microspheres. Micromachines 2023, 14, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevao, B.M.; Miletto, I.; Marchese, L.; Gianotti, E. Optimized Rhodamine B labeled mesoporous silica nanoparticles as fluorescent scaffolds for the immobilization of photosensitizers: A theranostic platform for optical imaging and photodynamic therapy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 9042–9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Ge, X.; Xu, B.Y.; Zhang, W.; Weitz, D.A. Microfluidic fabrication of microparticles for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 5646–5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, M.R.; Swaim, J.D.; Vollmer, F. Whispering gallery mode sensors. Adv. Opt. Photon. 2015, 7, 168–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (µm) | (µm) | (µm) | (µm) | Number of Daughters n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 ± 0.9 | 10 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.17 | 1.1 ± 0.17 | 1 |

| 50 ± 1.5 | 10 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.20 | 1.28 ± 0.19 | 4 |

| 70 ± 2.1 | 10 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.23 | 1.76 ± 0.26 | 8 |

| 90 ± 2.7 | 20 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.27 | 1.86 ± 0.28 | 4 |

| 120 ± 3.6 | 22 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 0.33 | 2.43 ± 0.36 | 6 |

| 130 ± 3.9 | 30 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 0.38 | 2.5 ± 0.38 | 4 |

| Method | Porosity (p) | Deviation from BET |

|---|---|---|

| WGM (Lorenz—Lorentz) | 62.0% | −0.8% |

| WGM (Bruggeman) | 63.3% | +0.5% |

| WGM (Maxwell–Garnett) | 65.0% | +2.2% |

| BET (reference) | 62.8% | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, Q.; Kouz, S.; Khan, A.; Hossain, N.; Bchellaoui, N.; El Abed, A.I. Highly Sensitive Measurement of the Refractive Index of Mesoporous Hollow Silica Microcapsules Using Whispering Gallery Mode Resonances. Sensors 2026, 26, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010250

Xu Q, Kouz S, Khan A, Hossain N, Bchellaoui N, El Abed AI. Highly Sensitive Measurement of the Refractive Index of Mesoporous Hollow Silica Microcapsules Using Whispering Gallery Mode Resonances. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010250

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Qisheng, Sadok Kouz, Aatir Khan, Naheed Hossain, Nizar Bchellaoui, and Abdel I. El Abed. 2026. "Highly Sensitive Measurement of the Refractive Index of Mesoporous Hollow Silica Microcapsules Using Whispering Gallery Mode Resonances" Sensors 26, no. 1: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010250

APA StyleXu, Q., Kouz, S., Khan, A., Hossain, N., Bchellaoui, N., & El Abed, A. I. (2026). Highly Sensitive Measurement of the Refractive Index of Mesoporous Hollow Silica Microcapsules Using Whispering Gallery Mode Resonances. Sensors, 26(1), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010250