DTD: Density Triangle Descriptor for 3D LiDAR Loop Closure Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

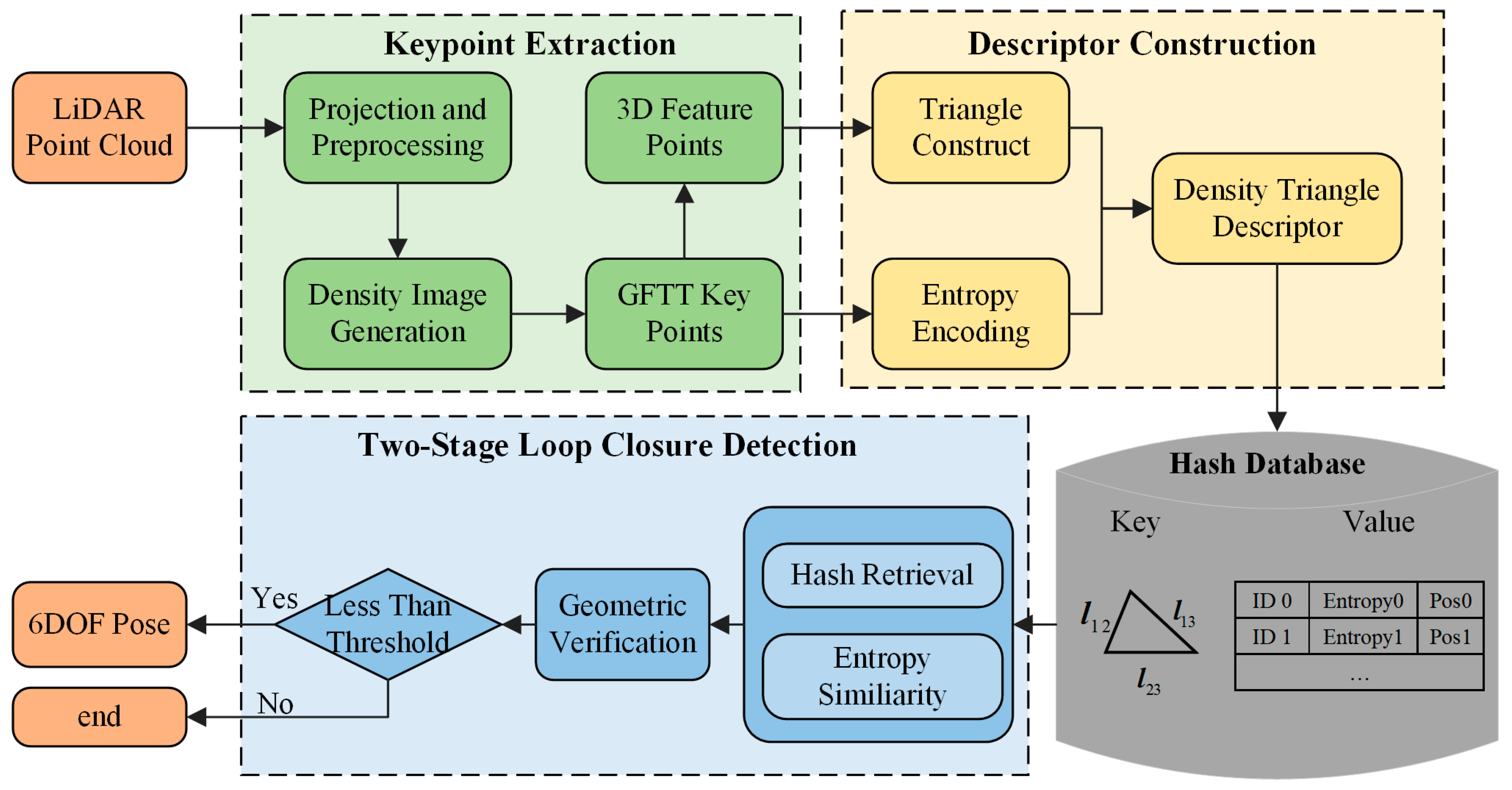

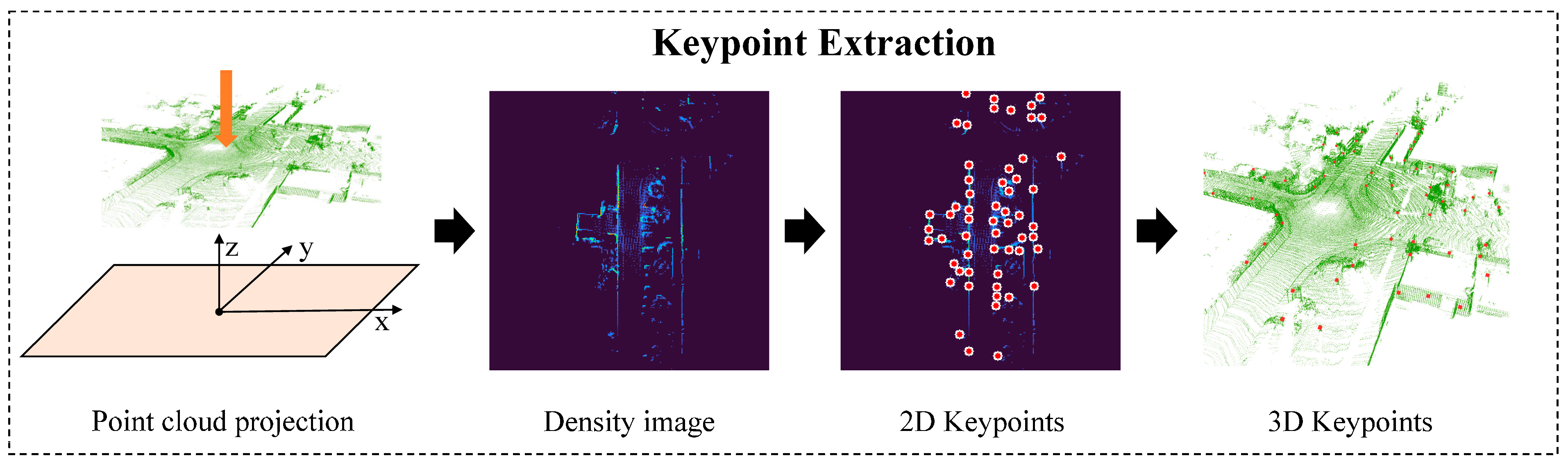

- We propose a novel Density Triangle Descriptor (DTD) based on density image features, which enables fast keypoint extraction from point cloud density maps and can be robustly applied to loop closure detection across various scenarios.

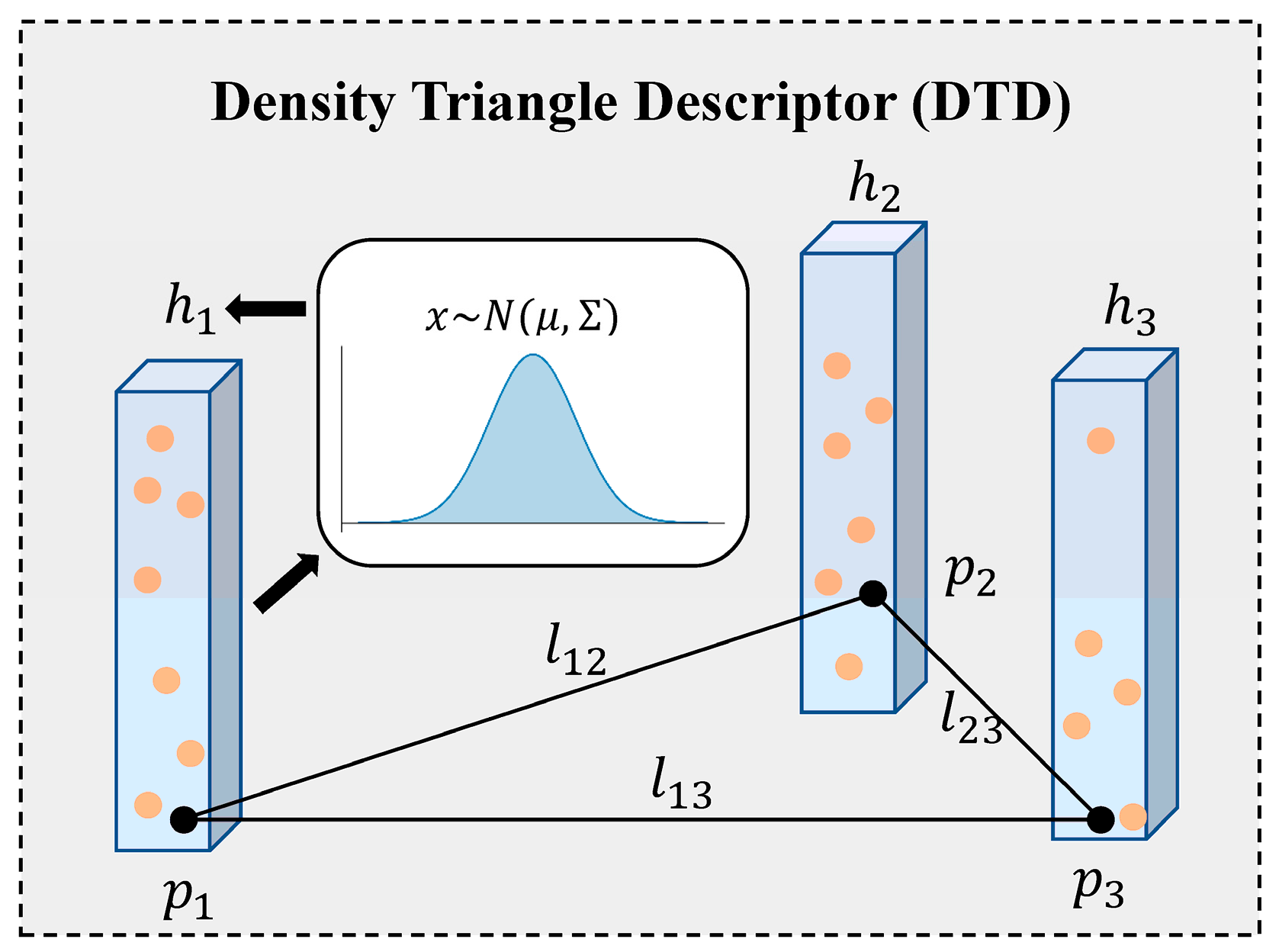

- We introduce an entropy-based local descriptor, in which the neighborhood of each keypoint is modeled as a Gaussian distribution, and entropy is employed to quantify local uncertainty, thereby enriching the expressiveness of DTD.

- We develop a two-stage loop closure detection method for DTD, consisting of candidate search and geometric verification, where an entropy-based similarity function is further incorporated to improve the real-time performance and robustness of the method.

- Extensive experiments across multiple scenarios demonstrate the effectiveness of our method, with results compared to state-of-the-art approaches.

2. Related Work

2.1. Vision-Based Loop Closure Detection

2.2. LiDAR-Based Loop Closure Detection

3. Methods

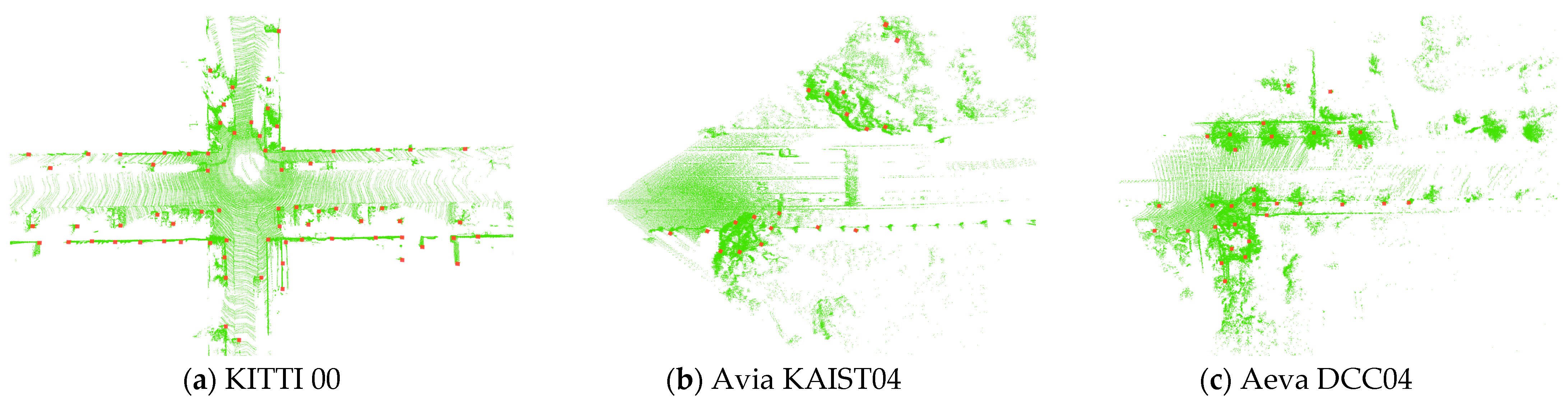

3.1. Keypoint Extraction

3.2. Density Triangle Descriptor Construction

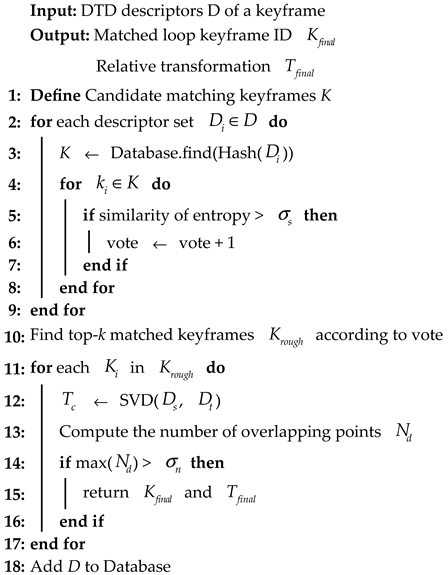

3.3. Loop Detection

| Algorithm 1: Loop Closure Detection |

|

4. Results

4.1. Dataset and Experimental Settings

4.2. Loop Detection Evaluation

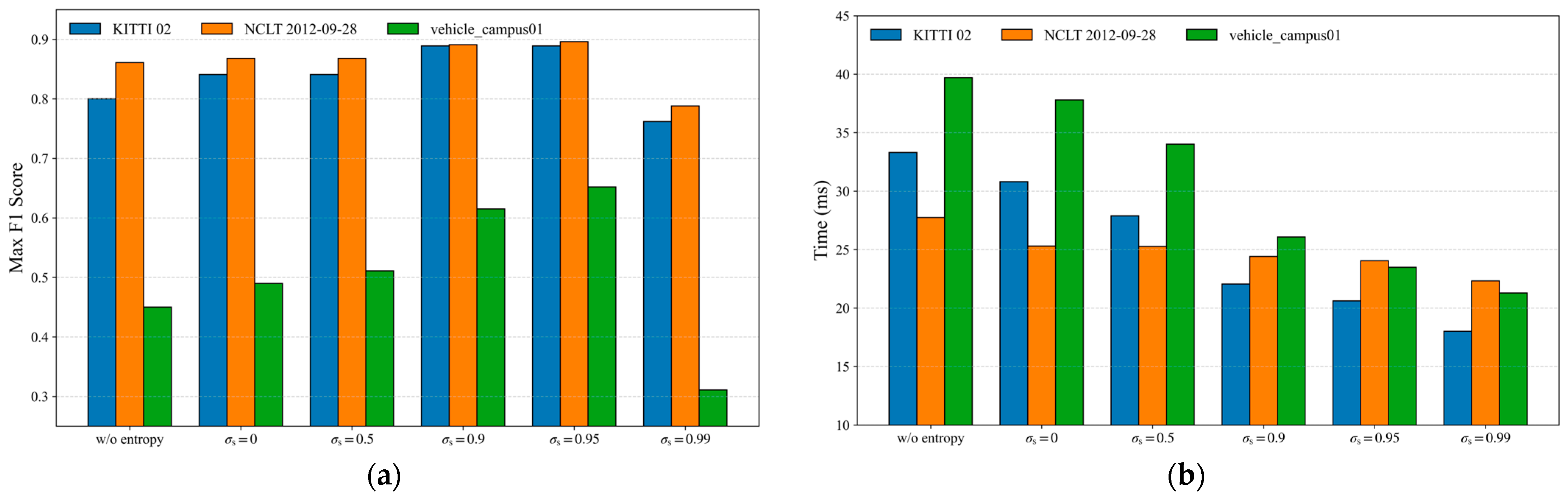

4.3. Ablation Study

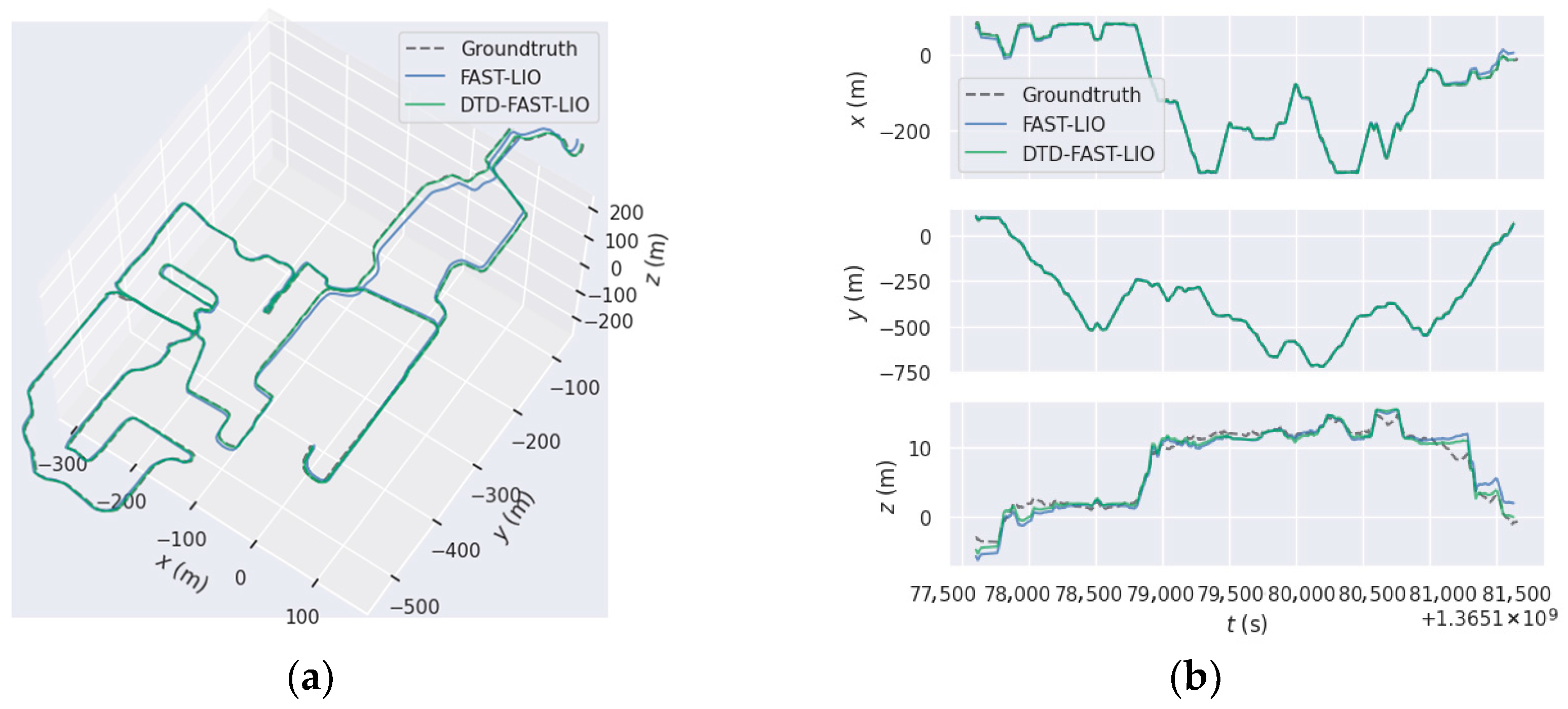

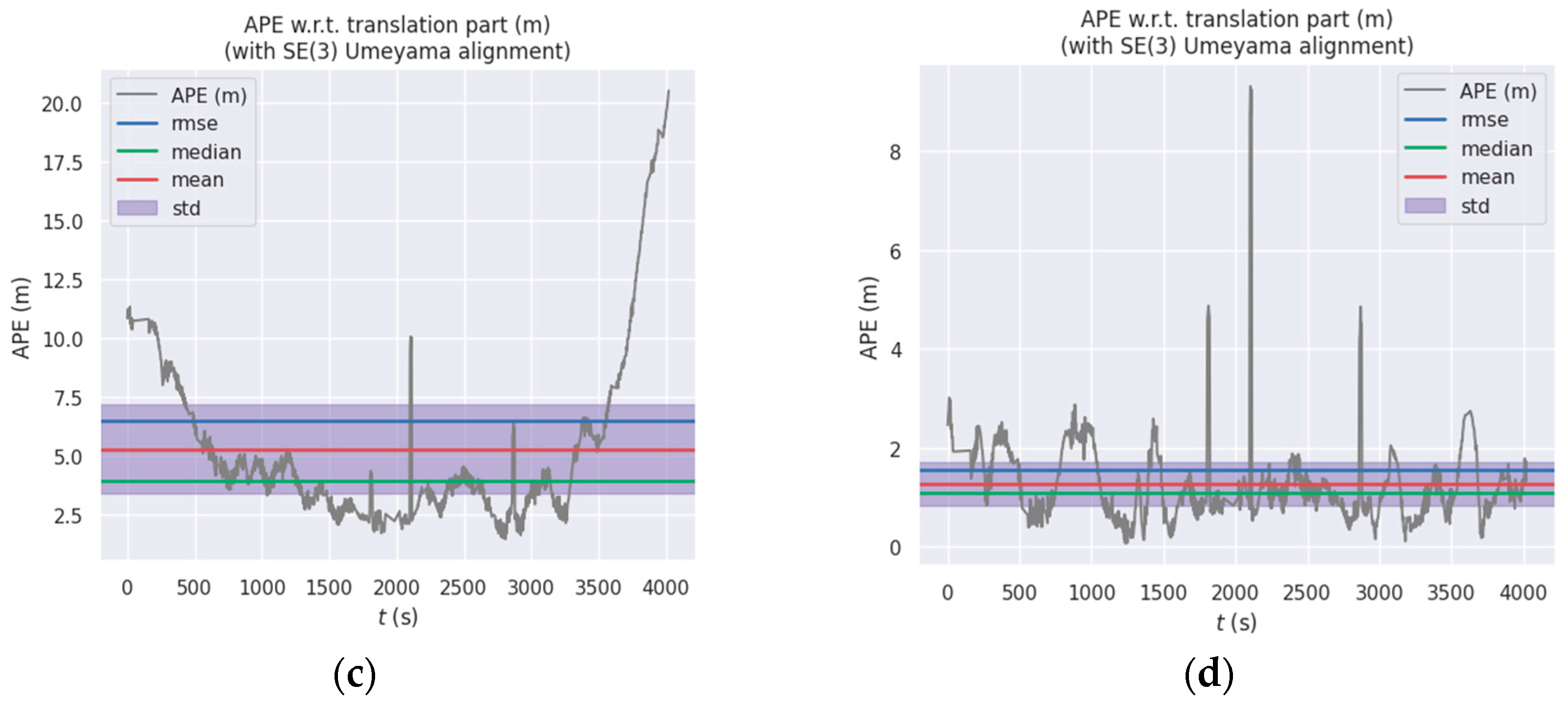

4.4. Performance on LiDAR-Based SLAM

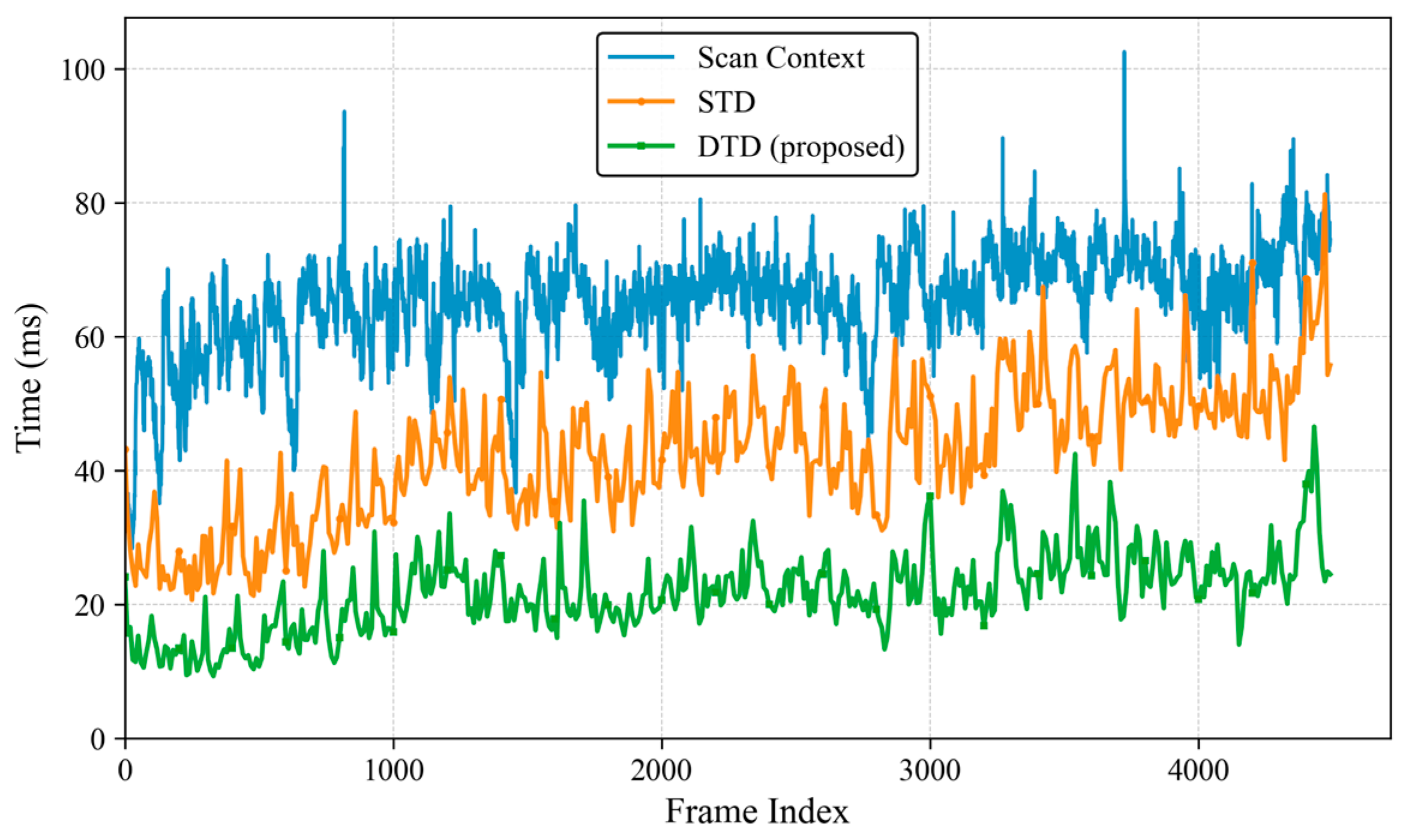

4.5. Computational Complexity

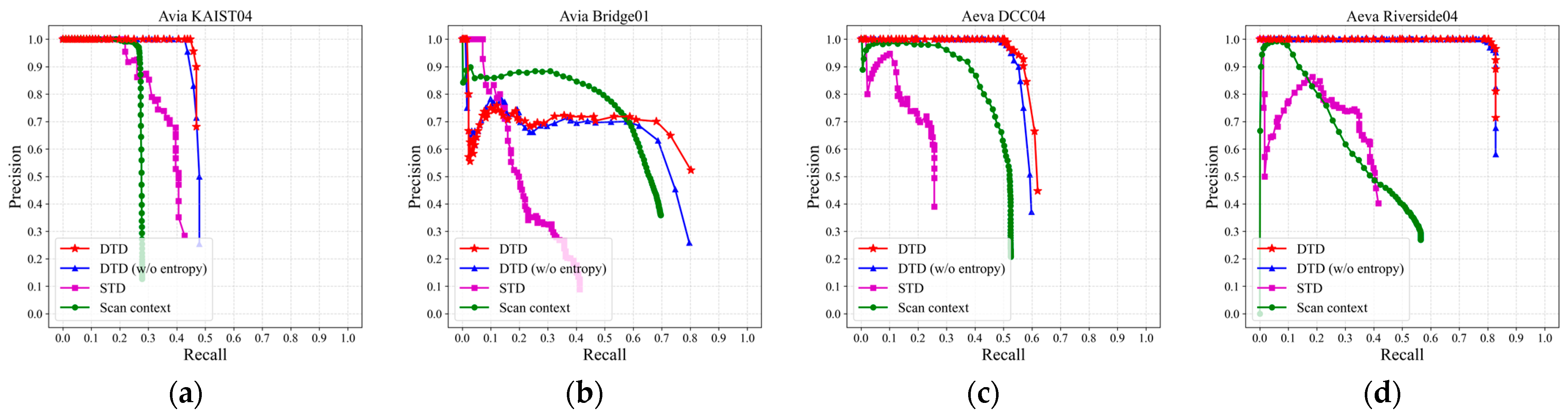

4.6. Applicability to Different LiDAR Types

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.; Meyers, D.; Wang, W.; Ratti, C.; Rus, D. LIO-SAM: Tightly-coupled Lidar Inertial Odometry via Smoothing and Mapping. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October 2020–24 January 2021; pp. 5135–5142. [Google Scholar]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A Versatile and Accurate Monocular SLAM System. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, B.; Jiang, F.; Lu, B.; Gu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Three-Dimensional Environment Mapping with a Rotary-Driven Lidar in Real Time. Sensors 2025, 25, 4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvez-López, D.; Tardos, J.D. Bags of Binary Words for Fast Place Recognition in Image Sequences. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2012, 28, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivoňka, T.; Přeučil, L. On Model-Free Re-Ranking for Visual Place Recognition with Deep Learned Local Features. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 7900–7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, Y.; Ren, Y.; Duan, G.; Zhang, H. Loop Detection Method Based on Neural Radiance Field BoW Model for Visual Inertial Navigation of UAVs. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H. M2DP: A Novel 3D Point Cloud Descriptor and Its Application in Loop Closure Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 9–14 October 2016; pp. 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Kim, A. Scan Context: Egocentric Spatial Descriptor for Place Recognition Within 3D Point Cloud Map. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; pp. 4802–4809. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Guadagnino, T.; Mersch, B.; Vizzo, I.; Stachniss, C. Effectively Detecting Loop Closures using Point Cloud Density Maps. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 10260–10266. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Pak, G.; Kim, E. RE-TRIP: Reflectivity Instance Augmented Triangle Descriptor for 3D Place Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Atlanta, GA, USA, 19–23 May 2025; pp. 2226–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C.; Lin, J.; Zou, Z.; Hong, X.; Zhang, F. STD: Stable Triangle Descriptor for 3D place recognition. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; pp. 1897–1903. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C.; Lin, J.; Liu, Z.; Wei, H.; Hong, X.; Zhang, F. BTC: A Binary and Triangle Combined Descriptor for 3-D Place Recognition. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 1580–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, F. BoW3D: Bag of Words for Real-Time Loop Closing in 3D LiDAR SLAM. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2828–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lu, S.; Wu, J.; Lu, H.; Zhu, Q.; Liao, Y.; Xiong, R.; Wang, Y. RING++: Roto-Translation Invariant Gram for Global Localization on a Sparse Scan Map. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 4616–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, H.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. SURF: Speeded up robust features. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2006, Graz, Austria, 7–13 May 2006; pp. 404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. ORB: An efficient alternative to SIFT or SURF. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 2564–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Calonder, M.; Lepetit, V.; Strecha, C.; Fua, P. BRIEF: Binary Robust Independent Elementary Features. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2010, Heraklion, Greece, 5–11 September 2010; pp. 778–792. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, R.; Newman, P. FAB-MAP 3D: Topological mapping with spatial and visual appearance. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 2649–2656. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Choi, S.; Kim, A. Scan Context++: Structural Place Recognition Robust to Rotation and Lateral Variations in Urban Environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 1856–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Du, X.; Luo, L.; Shen, J. FreSCo: Frequency-Domain Scan Context for LiDAR-based Place Recognition with Translation and Rotation Invariance. In Proceedings of the 2022 17th International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision (ICARCV), Singapore, 11–13 December 2022; pp. 576–583. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Xie, L. Intensity Scan Context: Coding Intensity and Geometry Relations for Loop Closure Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 2095–2101. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Yi, P.; Zhang, F.; Lei, J.; Hong, Y. STV-SC: Segmentation and Temporal Verification Enhanced Scan Context for Place Recognition in Unstructured Environment. Sensors 2022, 22, 8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; He, L.; Zhang, H.; Lin, X.; Guan, Y. NDD: A 3D Point Cloud Descriptor Based on Normal Distribution for Loop Closure Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 1328–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Uy, M.A.; Lee, G.H. PointNetVLAD: Deep Point Cloud Based Retrieval for Large-Scale Place Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4470–4479. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, R.Q.; Su, H.; Kaichun, M.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Arandjelovic, R.; Gronat, P.; Torii, A.; Pajdla, T.; Sivic, J. NetVLAD: CNN Architecture for Weakly Supervised Place Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 5297–5307. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.Y.L.; Läbe, T.; Milioto, A.; Röhling, T.; Vysotska, O.; Haag, A.; Behley, J.; Stachniss, C. OverlapNet: Loop Closing for LiDAR-based SLAM. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.11344. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Kong, X.; Zhao, X.; Huang, T.; Li, W.; Wen, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. SSC: Semantic Scan Context for Large-Scale Place Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 2092–2099. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.; Cao, S.-Y.; Li, X.; Xu, J.; Ai, R.; Yu, Z.; Chen, X. BEVPlace++: Fast, Robust, and Lightweight LiDAR Global Localization for Autonomous Ground Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2025, 41, 4479–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, Z.; Luo, M.; Li, E.; Jing, F. Intensity Triangle Descriptor Constructed from High-Resolution Spinning LiDAR Intensity Image for Loop Closure Detection. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 8937–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zheng, S.; Li, Y.; Fan, Y.; Yu, B.; Cao, S.-Y.; Li, J.; Shen, H.-L. BEVPlace: Learning LiDAR-based Place Recognition using Bird’s Eye View Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 8666–8675. [Google Scholar]

- Jianbo, S.; Tomasi. Good features to track. In Proceedings of the 1994 Proceedings of IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 21–23 June 1994; pp. 593–600. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Urtasun, R. Are we ready for autonomous driving? The KITTI vision benchmark suite. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; pp. 3354–3361. [Google Scholar]

- Carlevaris-Bianco, N.; Ushani, A.K.; Eustice, R.M. University of Michigan North Campus long-term vision and lidar dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2015, 35, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Wei, H.; Hu, T.; Hu, X.; Zhu, Y.; He, Z.; Wu, J.; Yu, J.; Xie, X.; Huang, H.; et al. FusionPortable: A Multi-Sensor Campus-Scene Dataset for Evaluation of Localization and Mapping Accuracy on Diverse Platforms. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 3851–3856. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, M.; Yang, W.; Lee, D.; Gil, H.; Kim, G.; Kim, A. HeLiPR: Heterogeneous LiDAR Dataset for inter-LiDAR Place Recognition under Spatiotemporal Variations. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.14590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cai, Y.; He, D.; Lin, J.; Zhang, F. FAST-LIO2: Fast Direct LiDAR-Inertial Odometry. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 2053–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | KITTI | NCLT | FusionPortable | HeLiPR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor | Spinning | Spinning | Spinning | Solid state | |

| Scanning Pattern | Repetitive | Repetitive | Repetitive | Non-Repetitive | |

| LiDAR | Velodyne HDL-64E | Velodyne HDL-32E | Ouster OS1-128 | Livox Avia | Aeva Aeries II |

| Field of View | 360° × 26.8° | 360° × 41.3° | 360° × 45° | 70° × 77° | 120° × 19.2° |

| Sequence | 00 | 26 May 2012 | ugv_transition00 | KAIST04 Bridge01 | DCC04 Riverside04 |

| 02 | 20 August 2012 | ugv_parking01 | |||

| 05 | 28 September 2012 | building_day | |||

| 08 | 5 April 2013 | vehicle_campus01 | |||

| Environment | Urban | Campus | Unstructured, Indoor | Campus, Bridge | |

| Sequence | DTD | DTD (w/o Entropy) | STD | Scan Context | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 Max | EP | F1 Max | EP | F1 Max | EP | F1 Max | EP | |

| KITTI 00 | 0.962 | 0.947 | 0.855 | 0.874 | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.962 | 0.963 |

| KITTI 02 | 0.889 | 0.897 | 0.800 | 0.833 | 0.815 | 0.813 | 0.810 | 0.450 |

| KITTI 05 | 0.976 | 0.976 | 0.958 | 0.960 | 0.964 | 0.964 | 0.948 | 0.939 |

| KITTI 08 | 0.989 | 0.989 | 0.978 | 0.978 | 0.939 | 0.814 | 0.761 | 0.563 |

| NCLT 26 May 2012 | 0.879 | 0.850 | 0.850 | 0.850 | 0.840 | 0.612 | 0.766 | 0.503 |

| NCLT 20 August 2012 | 0.836 | 0.845 | 0.816 | 0.839 | 0.729 | 0.595 | 0.733 | 0.501 |

| NCLT 28 September 2012 | 0.896 | 0.884 | 0.861 | 0.863 | 0.618 | 0.562 | 0.771 | 0.517 |

| NCLT 5 April 2013 | 0.912 | 0.919 | 0.836 | 0.855 | 0.628 | 0.532 | 0.709 | 0.536 |

| ugv_transition00 | 0.923 | 0.929 | 0.909 | 0.916 | 0.884 | 0.643 | 0.744 | 0.752 |

| ugv_parking01 | 0.908 | 0.833 | 0.879 | 0.800 | 0.569 | 0.567 | 0.649 | 0.689 |

| building_day | 0.674 | 0.681 | 0.633 | 0.638 | 0.222 | 0.521 | 0.664 | 0.611 |

| vehicle_campus01 | 0.652 | 0.643 | 0.450 | 0.589 | 0.526 | 0.679 | 0.388 | 0 |

| Sequence | FAST-LIO | DTD-FAST-LIO | STD-FAST-LIO | SC-FAST-LIO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | Mean | RMSE | Mean | RMSE | Mean | RMSE | Mean | |

| NCLT 26 May 2012 | 2.382 | 2.066 | 1.574 | 1.346 | 1.608 | 1.386 | 1.635 | 1.402 |

| NCLT 20 August 2012 | 2.288 | 2.064 | 1.598 | 1.399 | 1.675 | 1.450 | 1.618 | 1.387 |

| NCLT 28 September 2012 | 2.930 | 2.231 | 1.057 | 0.923 | 1.188 | 1.030 | 1.931 | 1.408 |

| NCLT 5 April 2013 | 6.474 | 5.272 | 1.550 | 1.273 | 2.978 | 2.529 | 3.322 | 2.816 |

| ugv_transition00 | 0.201 | 0.147 | 0.201 | 0.147 | 0.203 | 0.149 | 0.201 | 0.147 |

| ugv_parking01 | 0.382 | 0.332 | 0.359 | 0.312 | 0.386 | 0.331 | 0.363 | 0.318 |

| building_day | 1.560 | 1.333 | 1.514 | 1.241 | 1.531 | 1.258 | 1.545 | 1.308 |

| vehicle_campus01 | 5.049 | 3.971 | 5.047 | 3.968 | 5.050 | 3.971 | 5.053 | 3.973 |

| Method | Time Consumption (ms) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Construction | Loop Detection | Add to Database | Total | |

| Scan Context | 47.063 | 30.289 | 0.017 | 77.517 |

| STD | 27.249 | 13.661 | 0.099 | 41.009 |

| DTD | 13.498 | 6.573 | 0.198 | 20.269 |

| Sequence | DTD | DTD (w/o Entropy) | STD | Scan Context | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 Max | EP | F1 Max | EP | F1 Max | EP | F1 Max | EP | |

| Avia KAIST04 | 0.620 | 0.724 | 0.600 | 0.714 | 0.500 | 0.609 | 0.419 | 0.593 |

| Avia Bridge01 | 0.691 | 0.508 | 0.658 | 0.506 | 0.319 | 0.536 | 0.637 | 0.500 |

| Aeva DCC04 | 0.706 | 0.751 | 0.685 | 0.743 | 0.362 | 0.508 | 0.570 | 0.501 |

| Aeva Riverside04 | 0.892 | 0.901 | 0.885 | 0.891 | 0.478 | 0.506 | 0.452 | 0.500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, K.; Wang, Q.; Yan, C.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S. DTD: Density Triangle Descriptor for 3D LiDAR Loop Closure Detection. Sensors 2026, 26, 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010201

Tang K, Wang Q, Yan C, Sun Y, Liu S. DTD: Density Triangle Descriptor for 3D LiDAR Loop Closure Detection. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):201. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010201

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Kaiwei, Qing Wang, Chao Yan, Yang Sun, and Shengyi Liu. 2026. "DTD: Density Triangle Descriptor for 3D LiDAR Loop Closure Detection" Sensors 26, no. 1: 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010201

APA StyleTang, K., Wang, Q., Yan, C., Sun, Y., & Liu, S. (2026). DTD: Density Triangle Descriptor for 3D LiDAR Loop Closure Detection. Sensors, 26(1), 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010201