A Multiport Network-Based Integrated Sensing System Using Rectangular Cavity Resonators for Volatile Organic Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

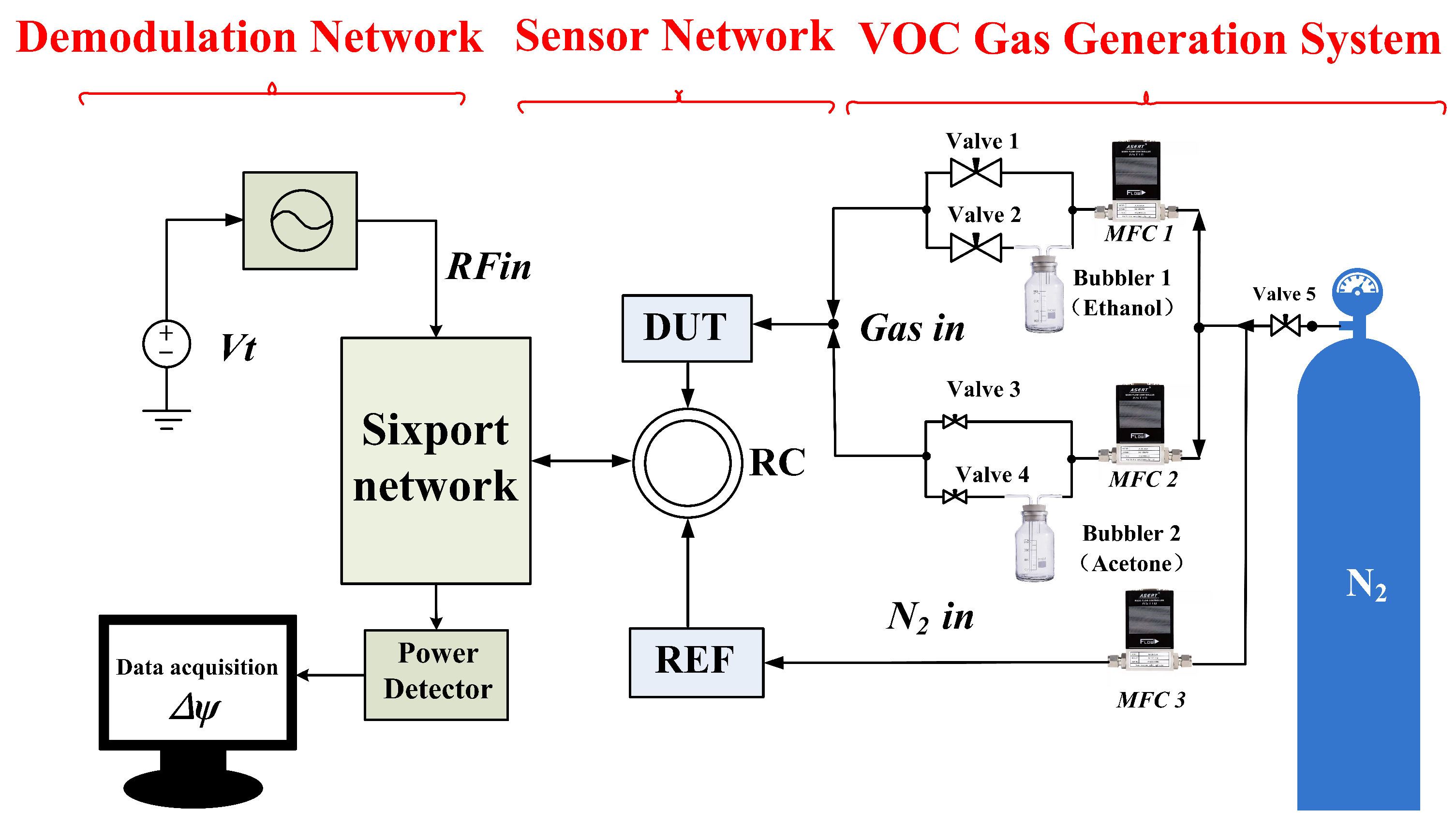

2. Theoretical Analysis of VOC Sensors Based on Multiport Network

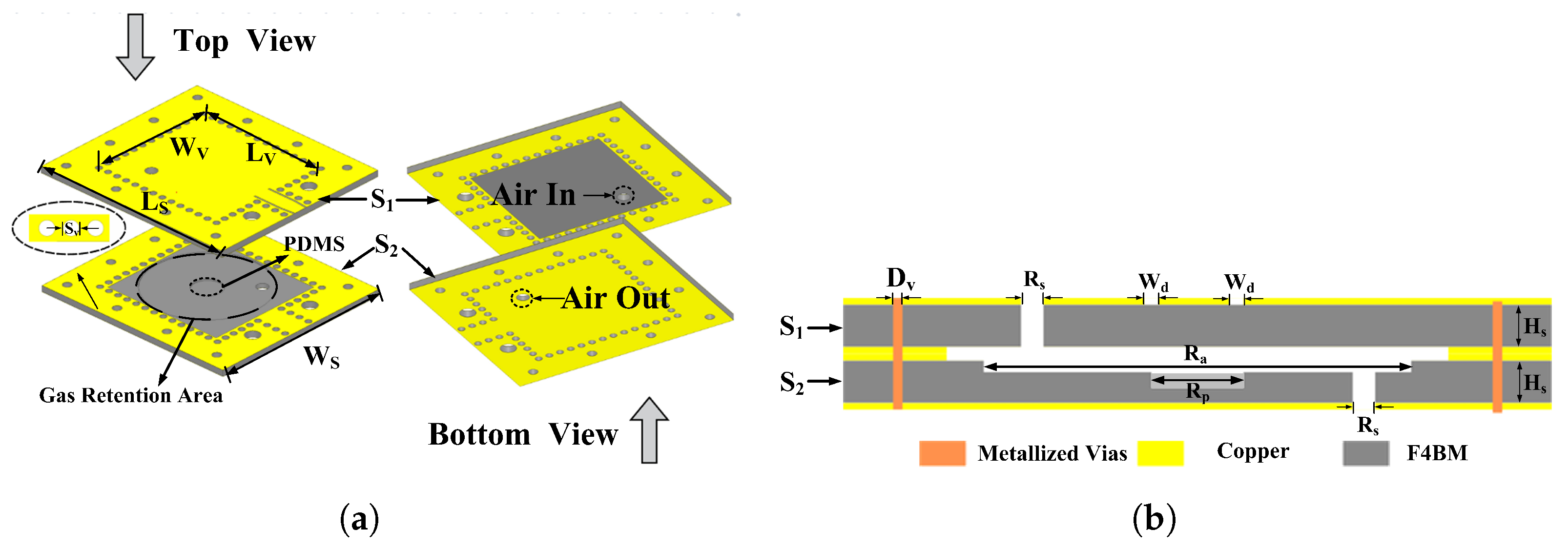

2.1. Structural Design of RCR

2.2. Analysis of Reflection Response

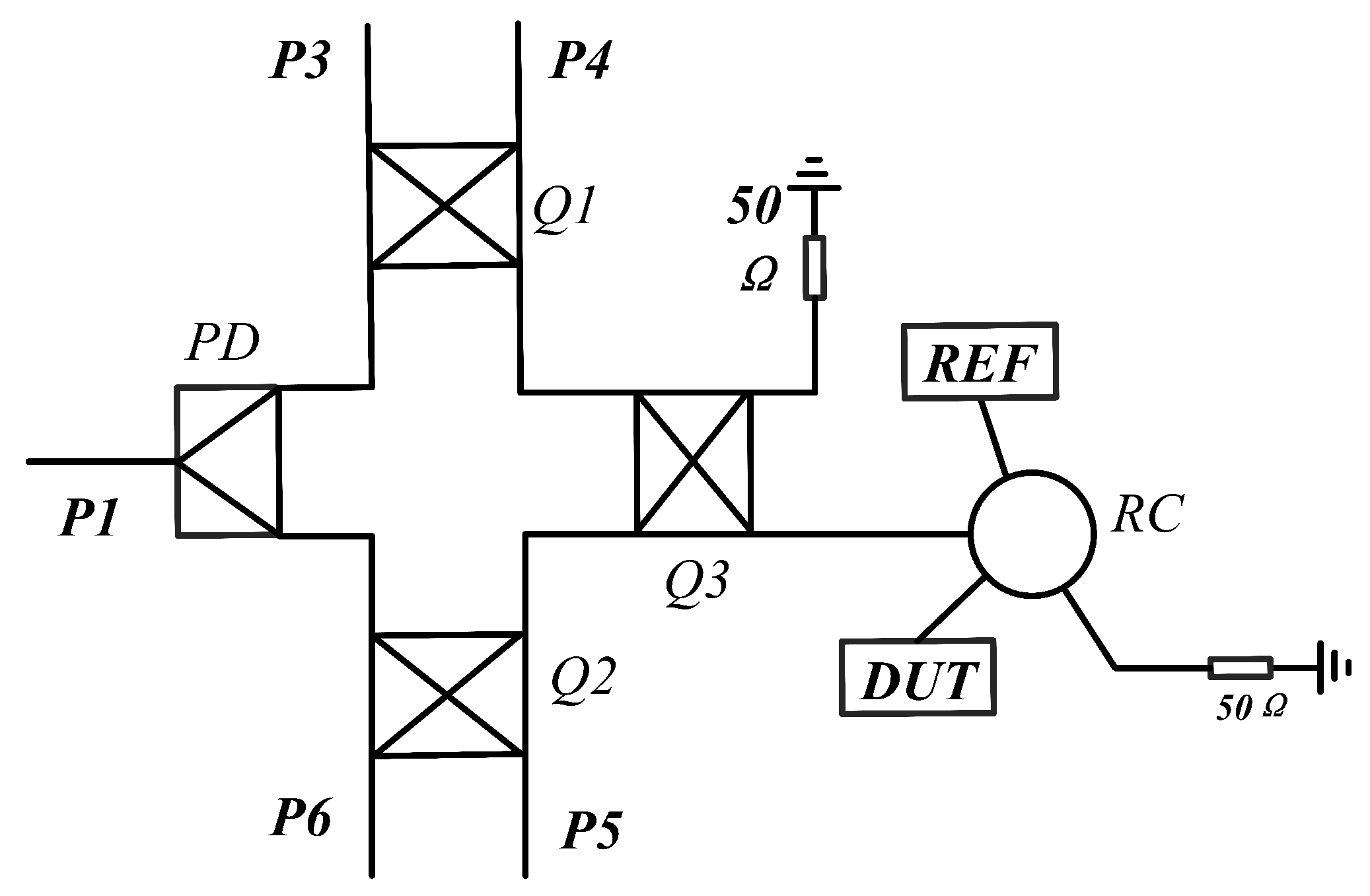

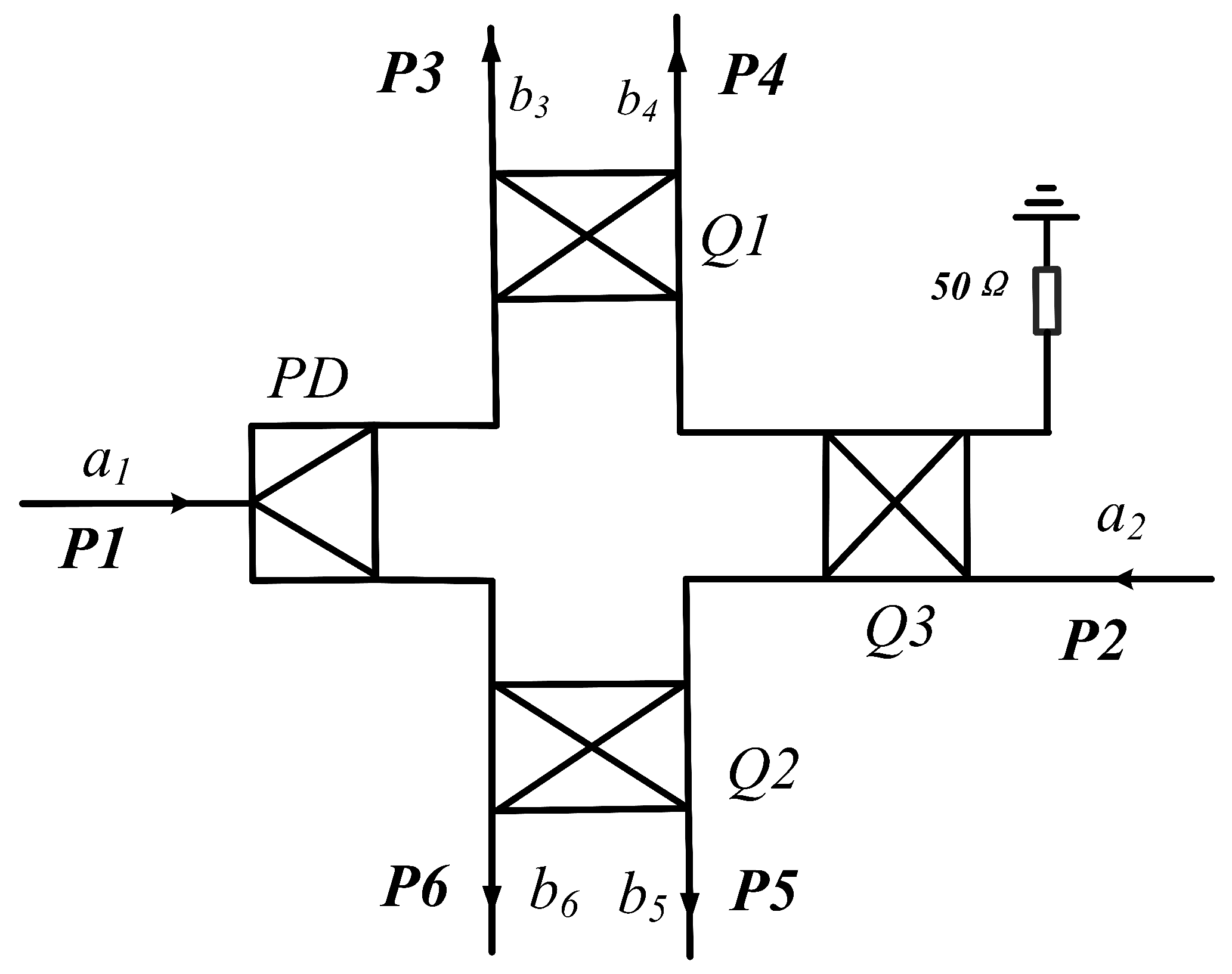

2.3. Theory and Design of Six-Port Demodulation Networks

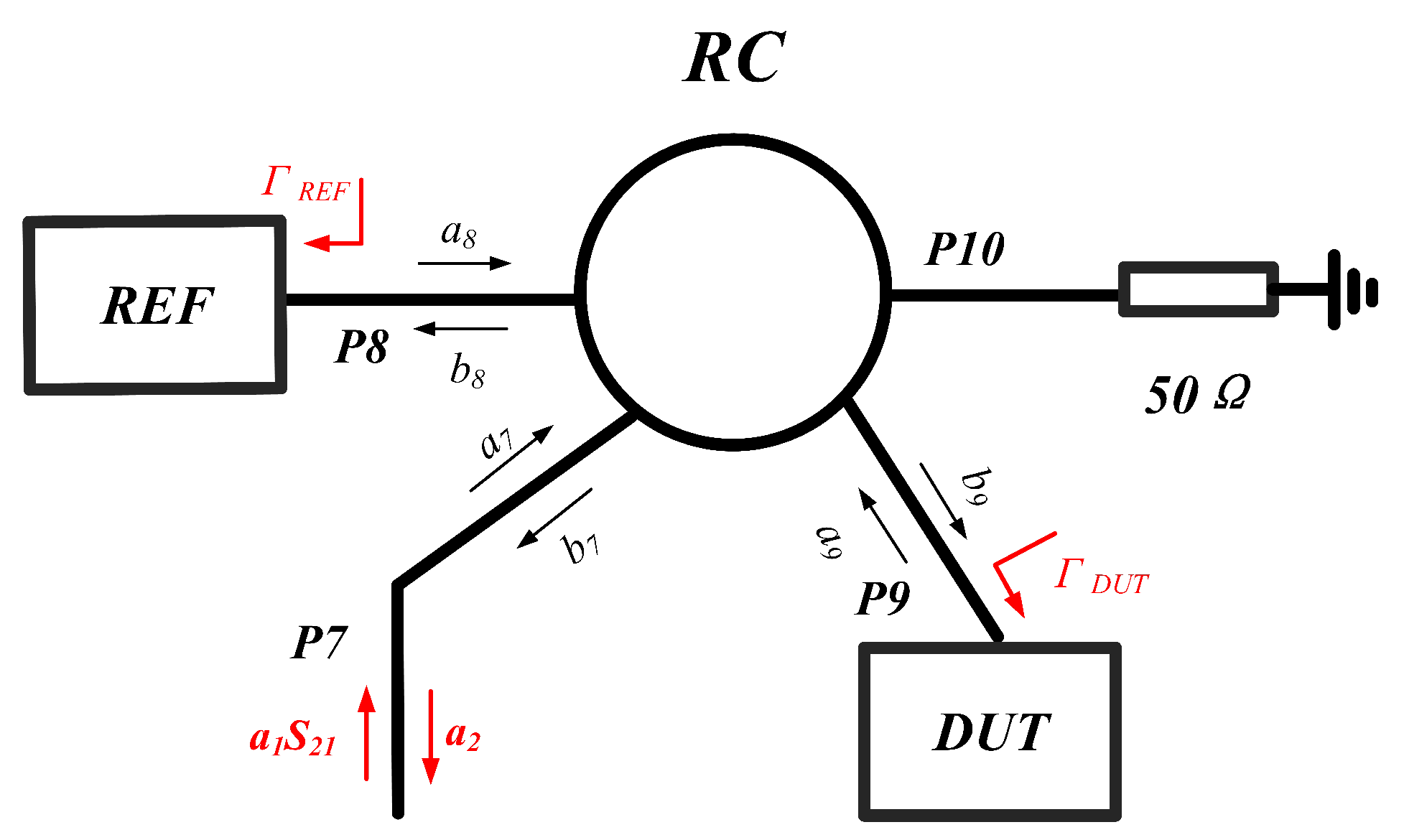

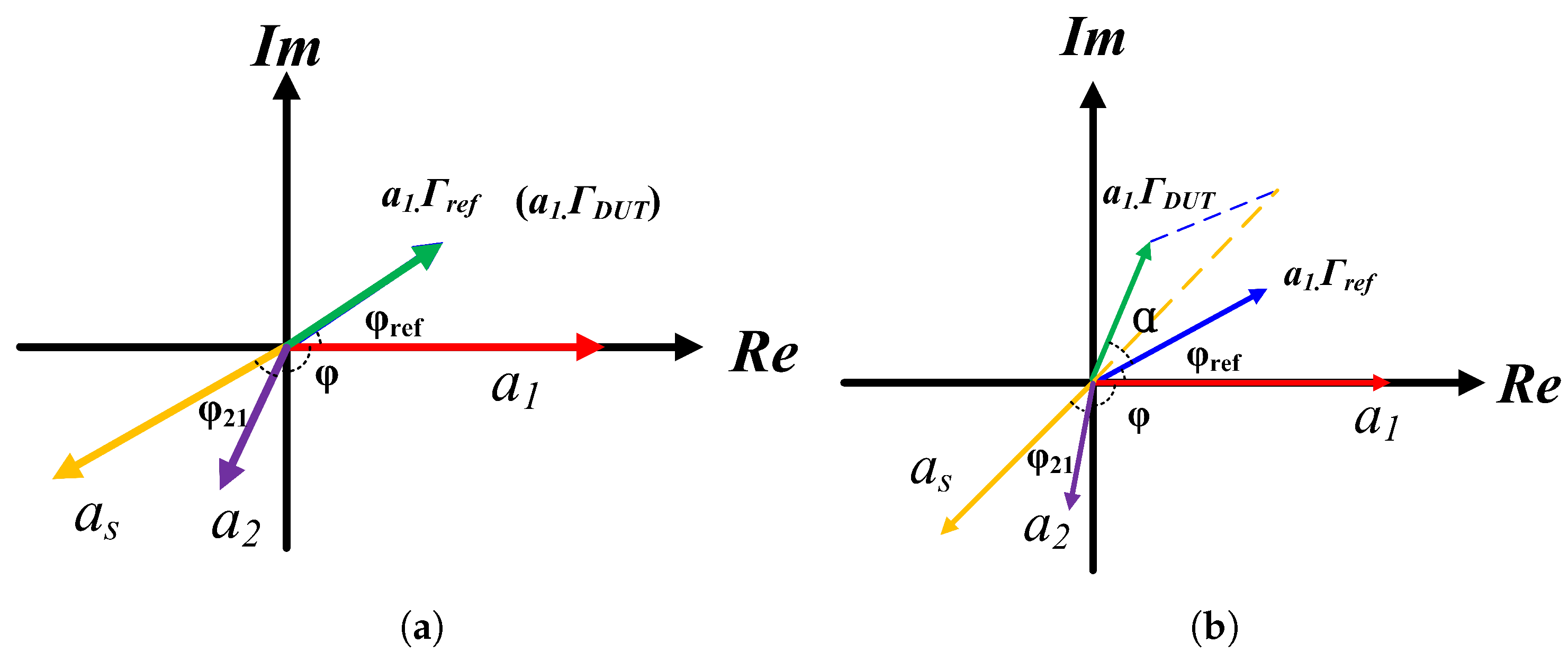

2.4. Analysis of Sensor Networks

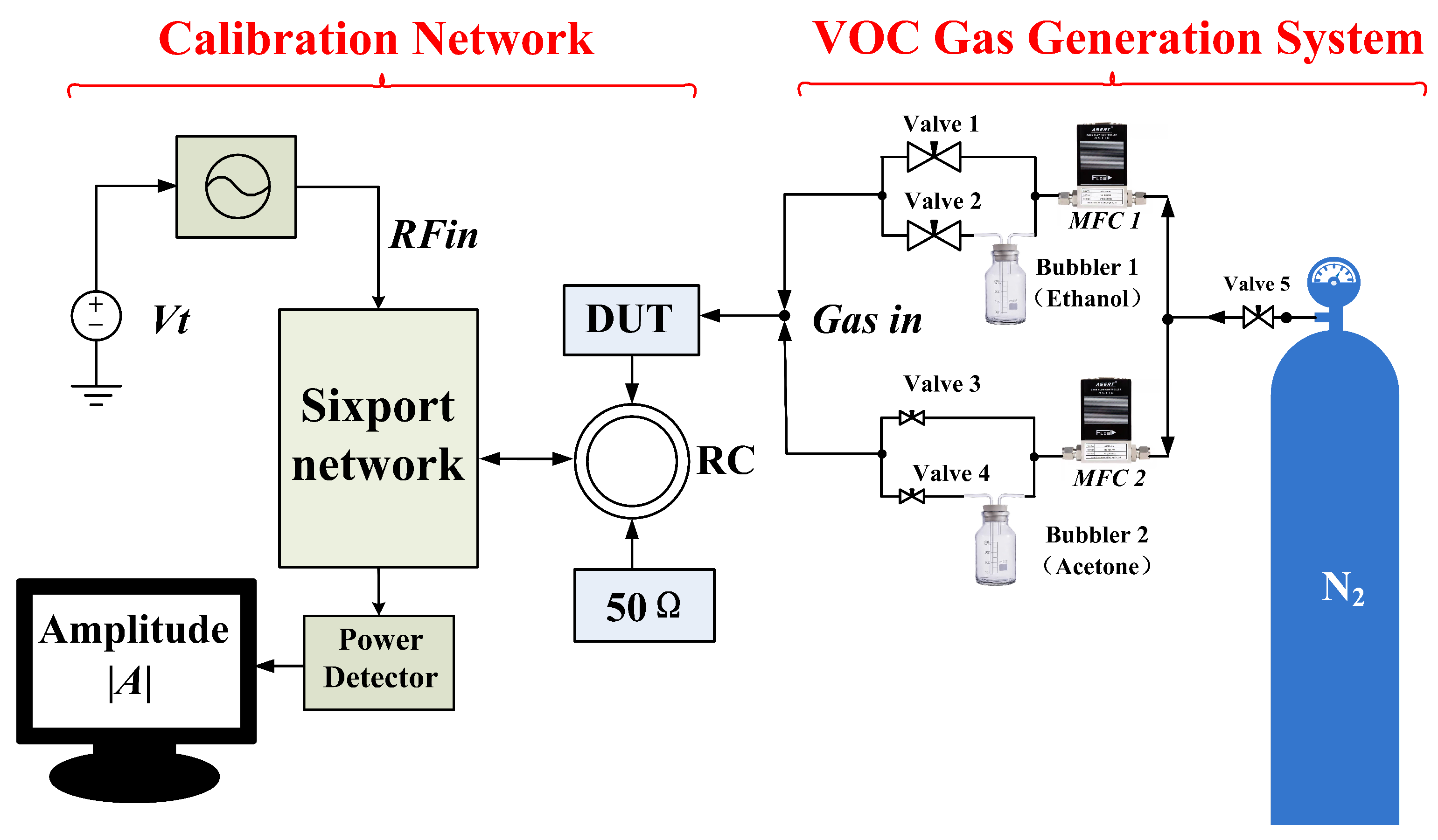

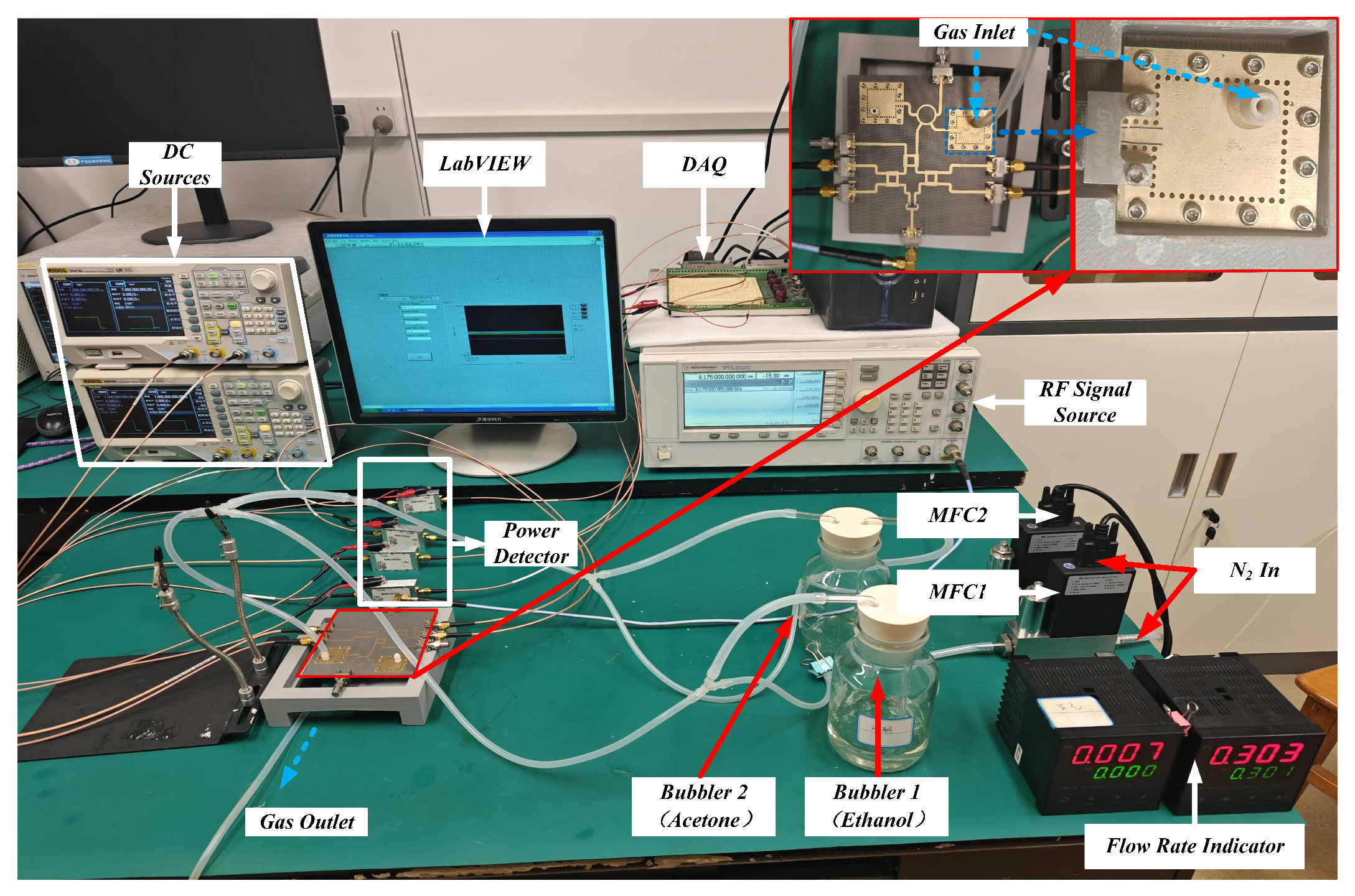

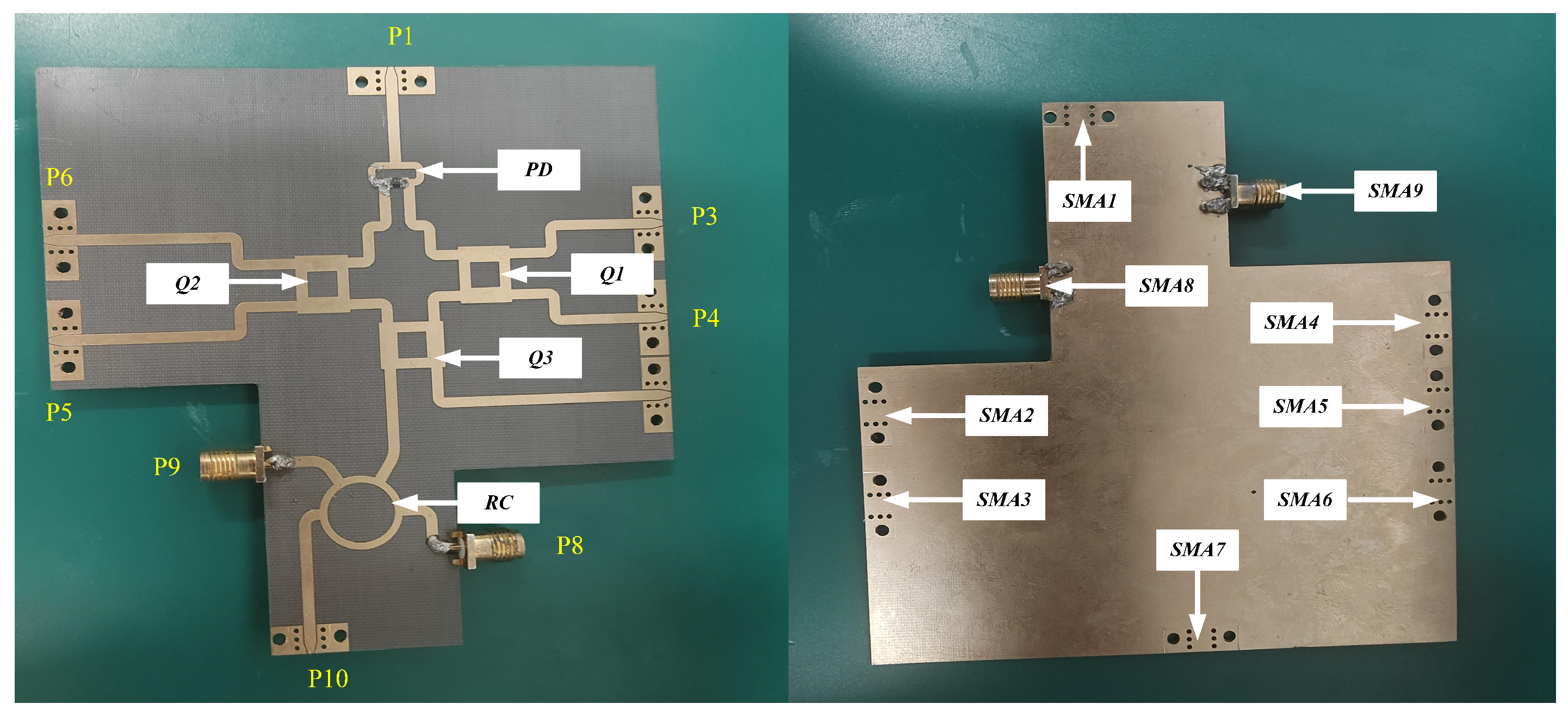

3. Description of the Test Platform

4. Measurement Results and Analysis

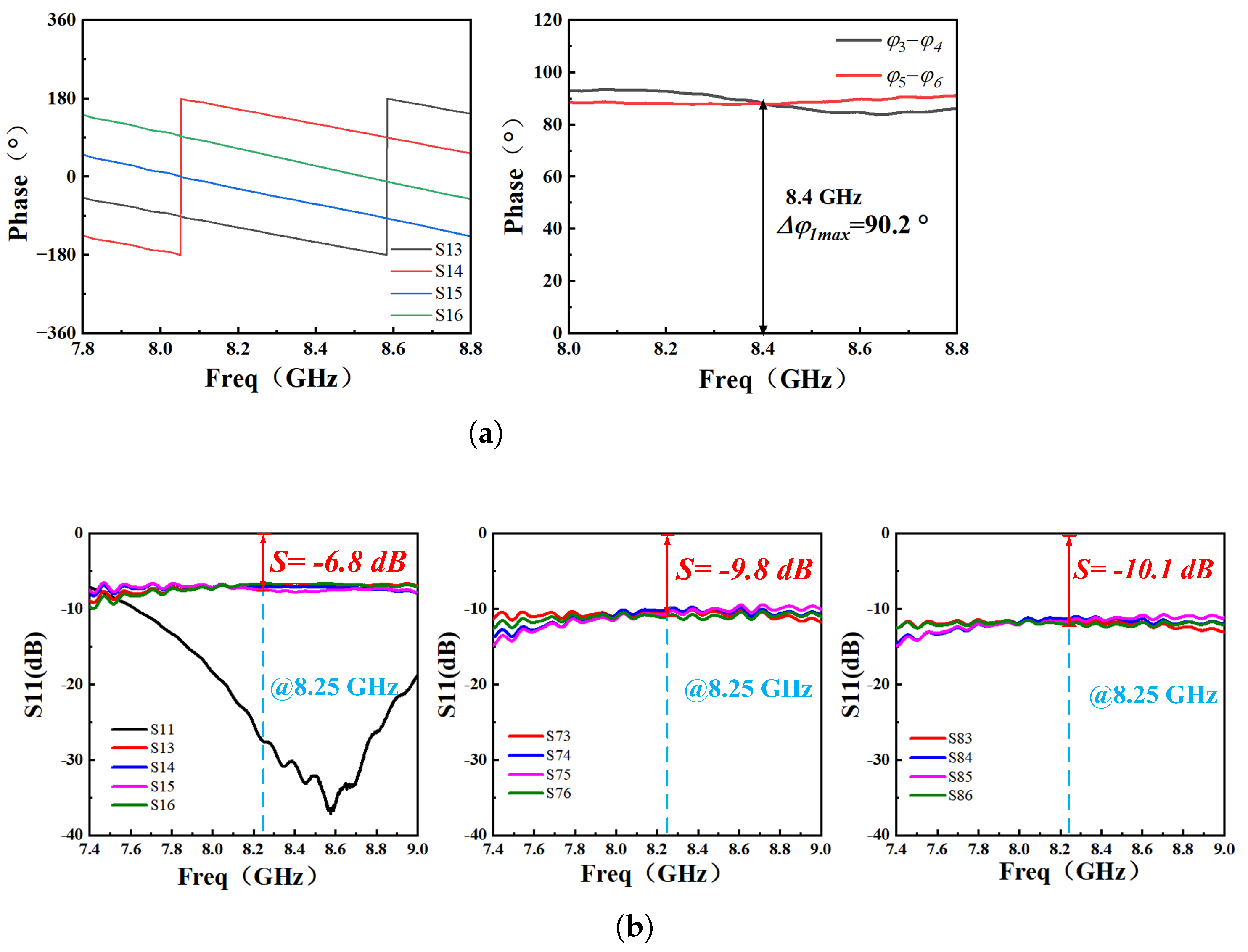

4.1. Component Functionality Testing

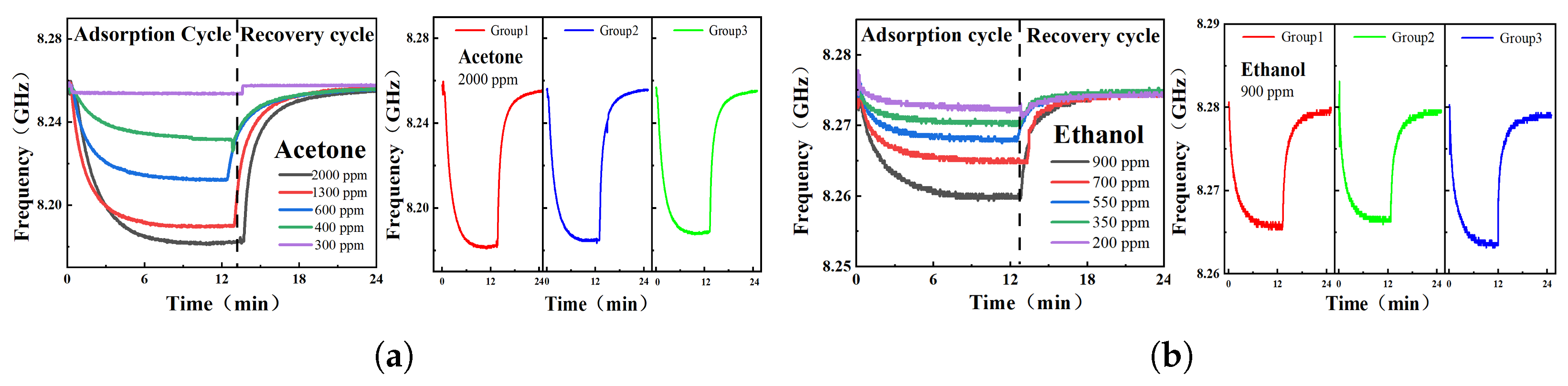

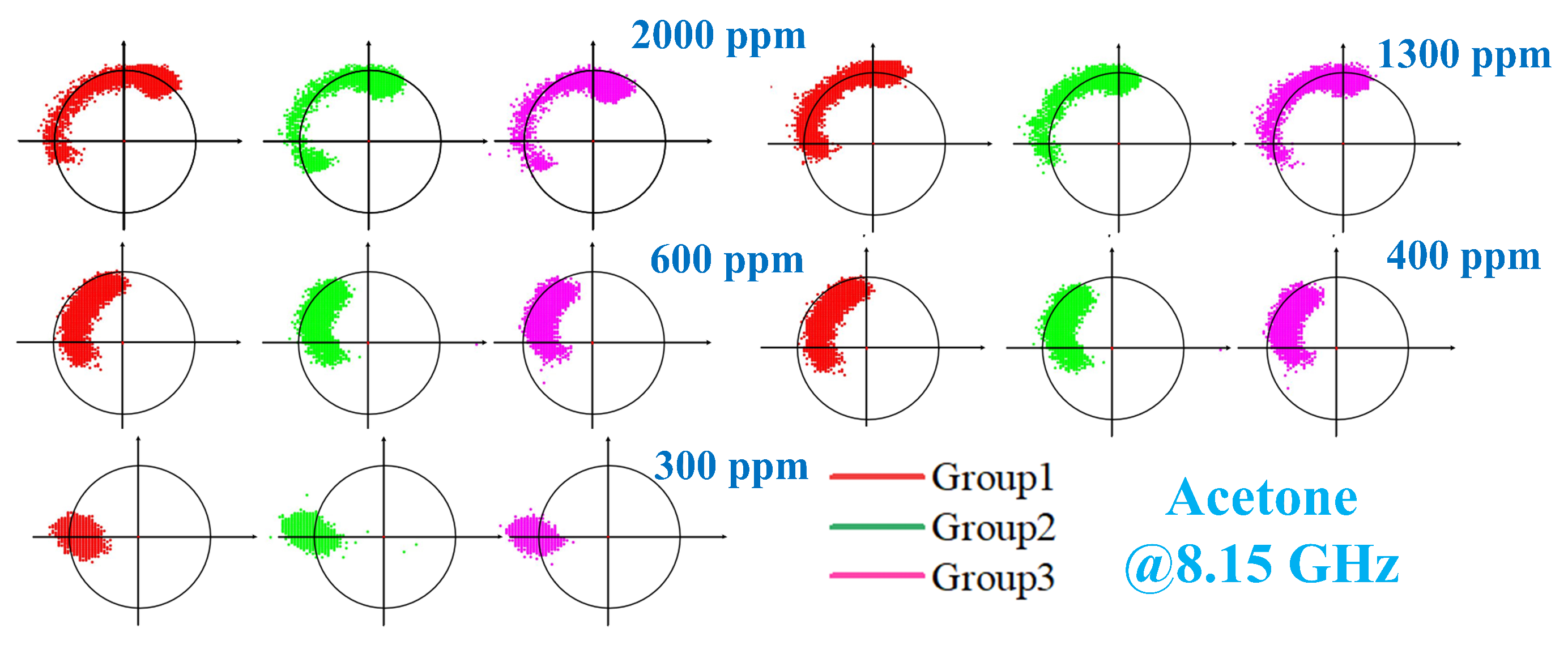

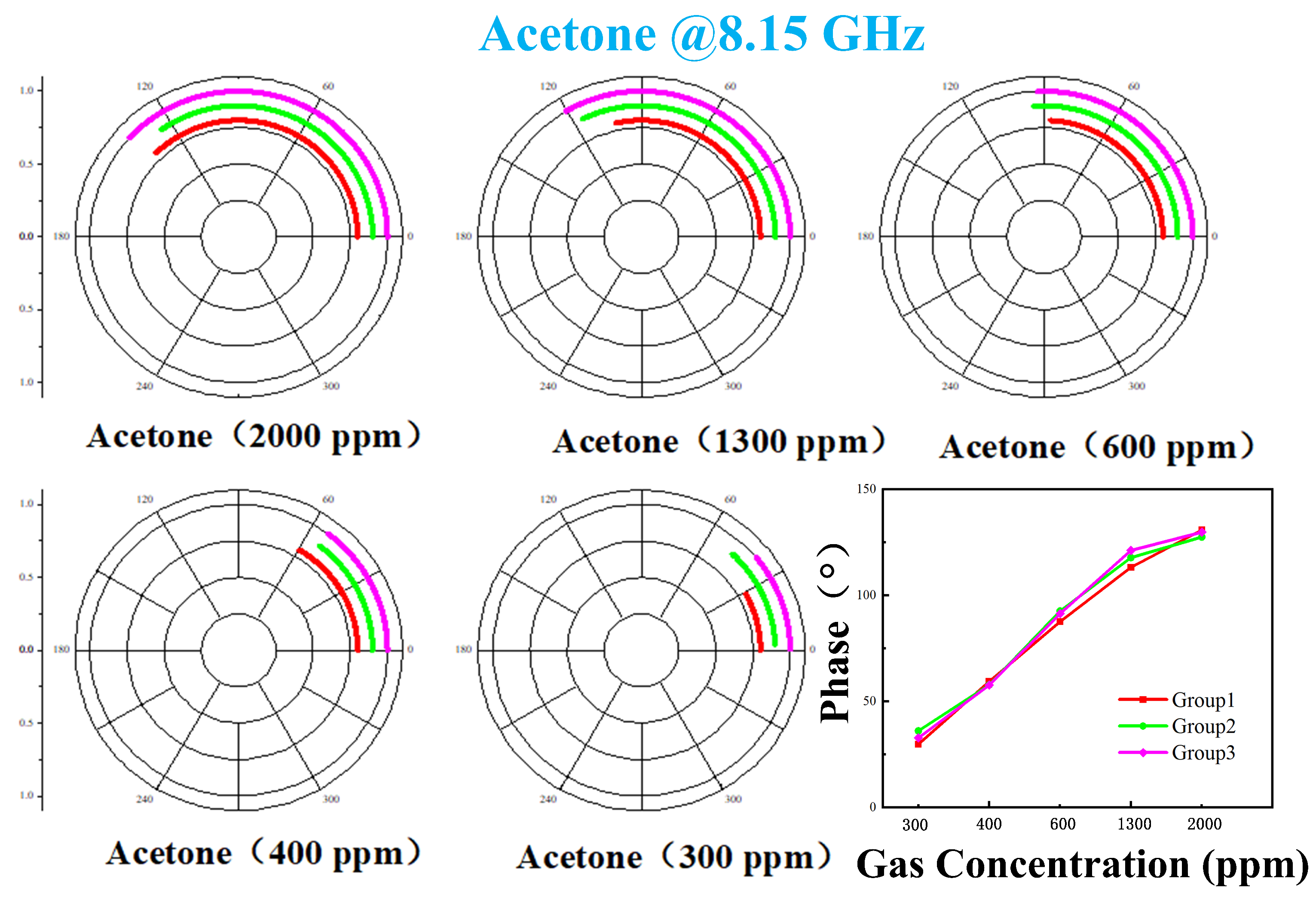

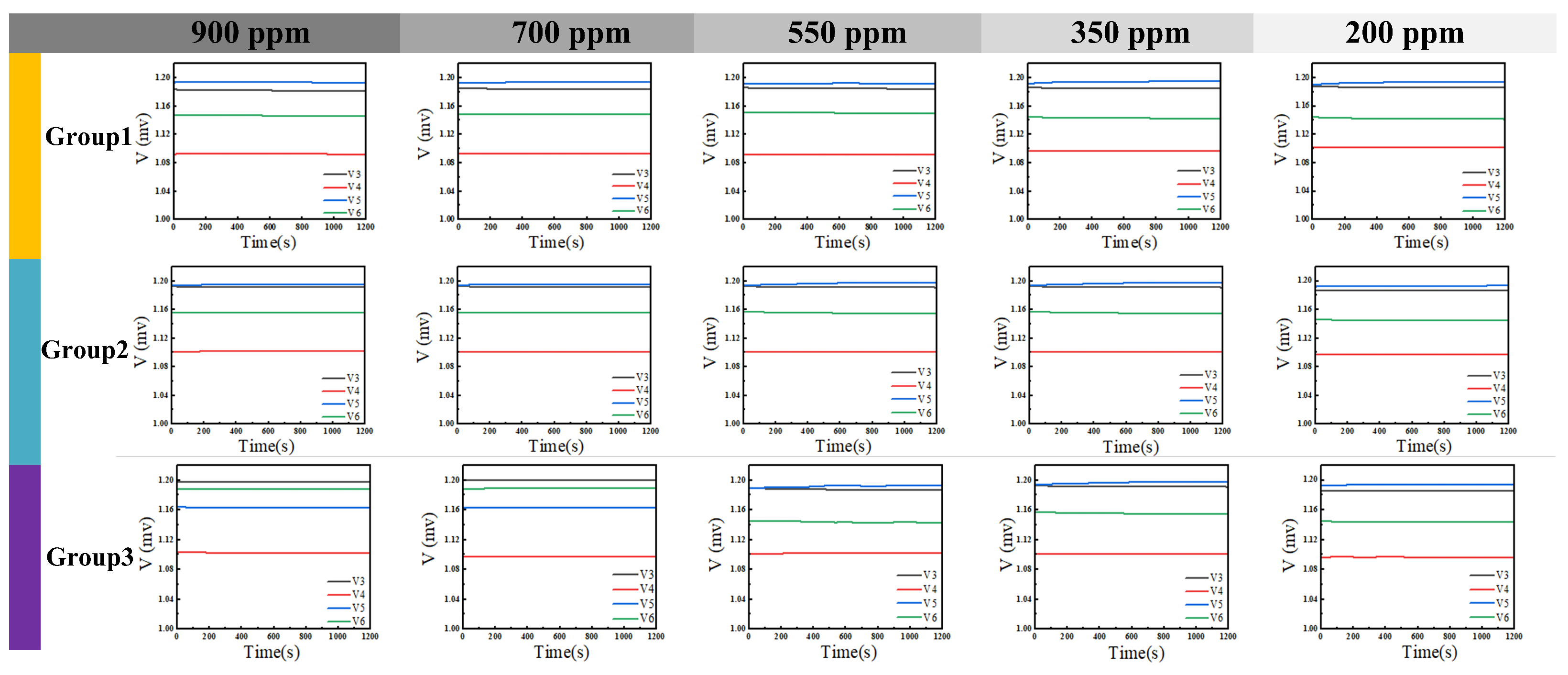

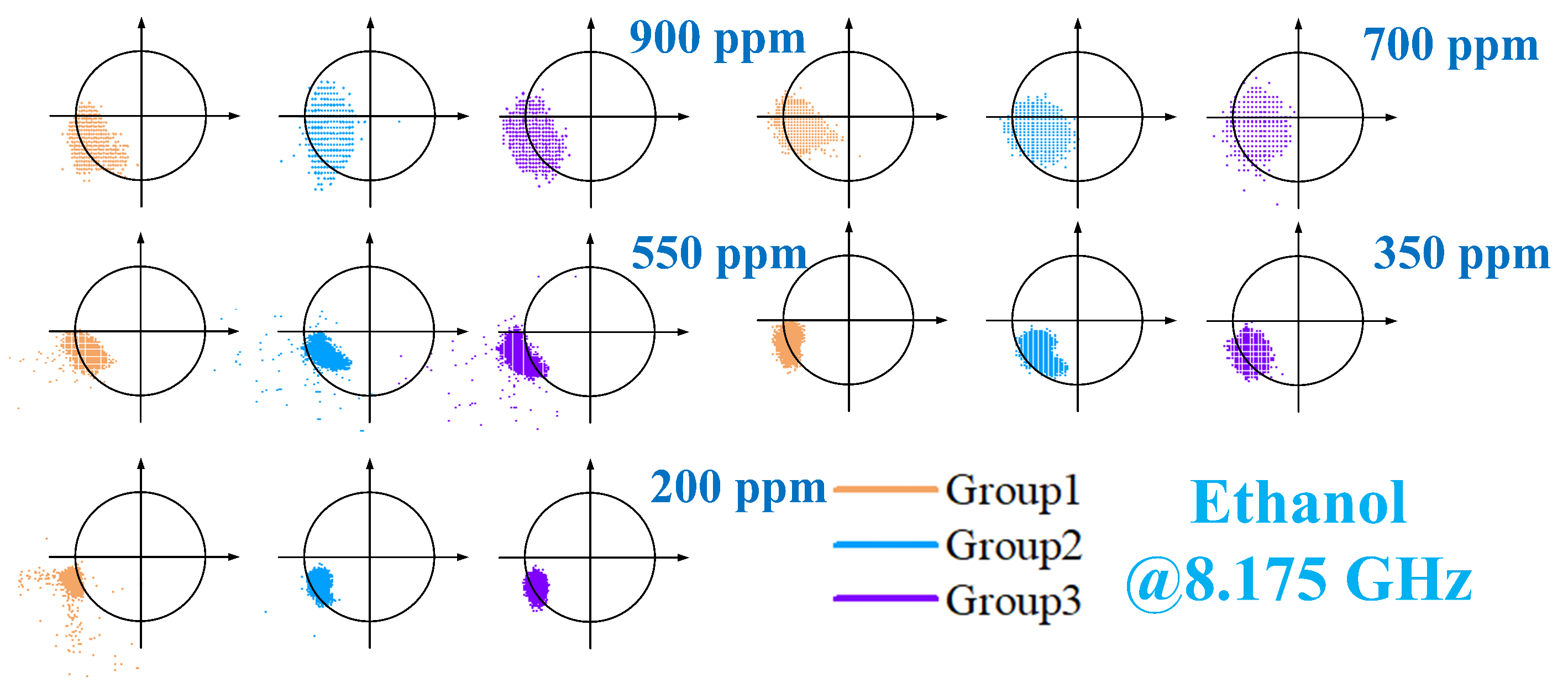

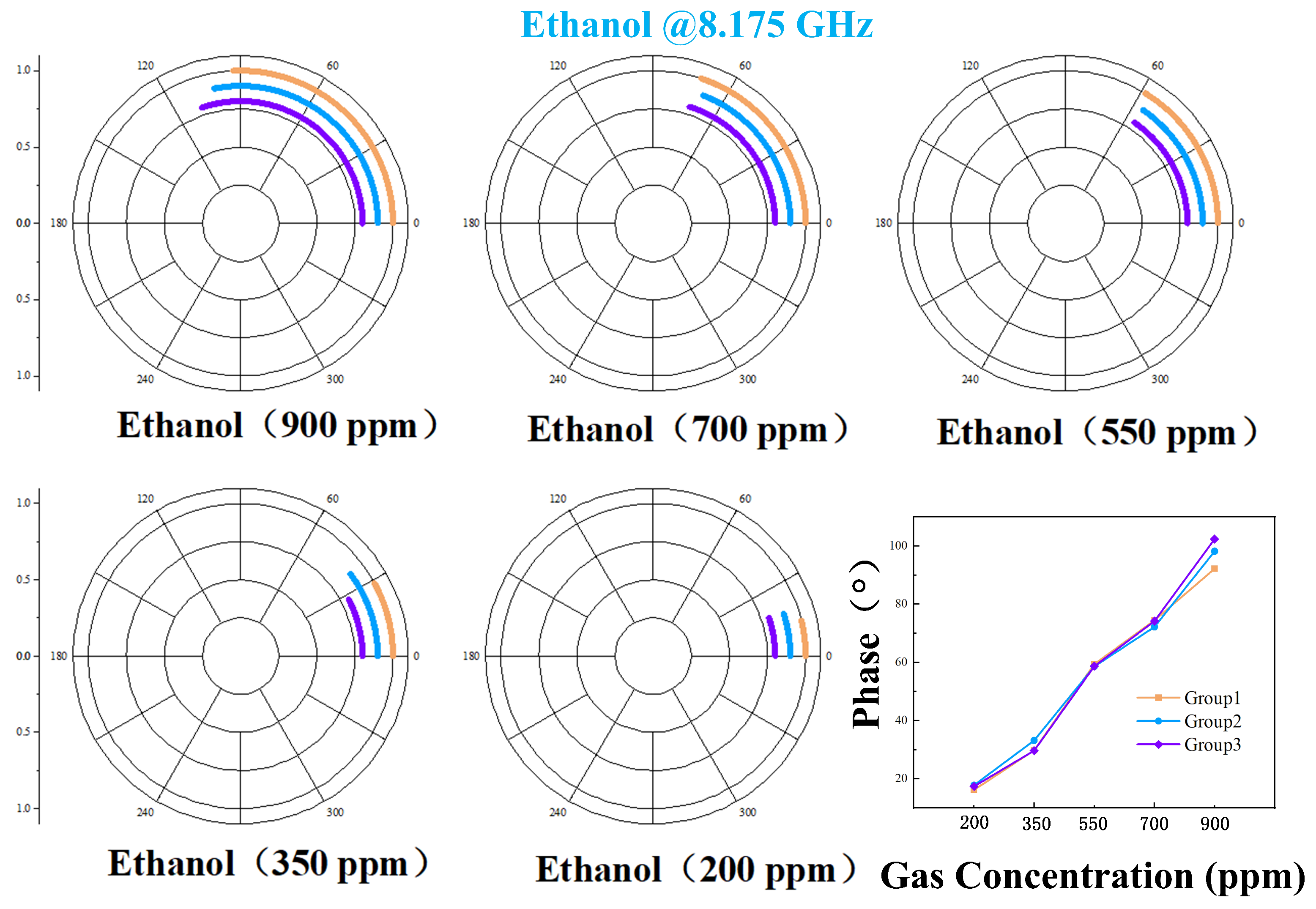

4.2. Phase Response of VOCs

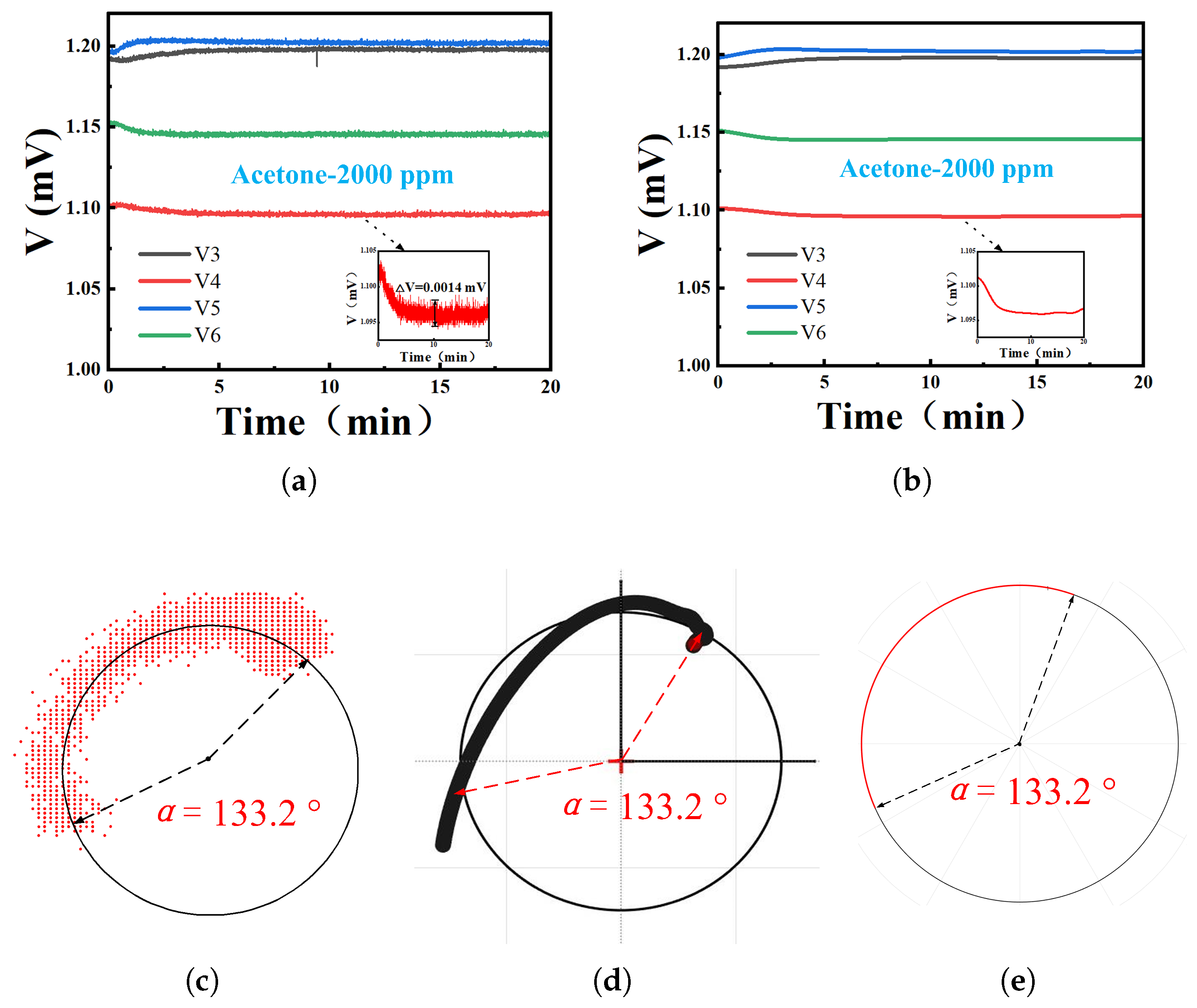

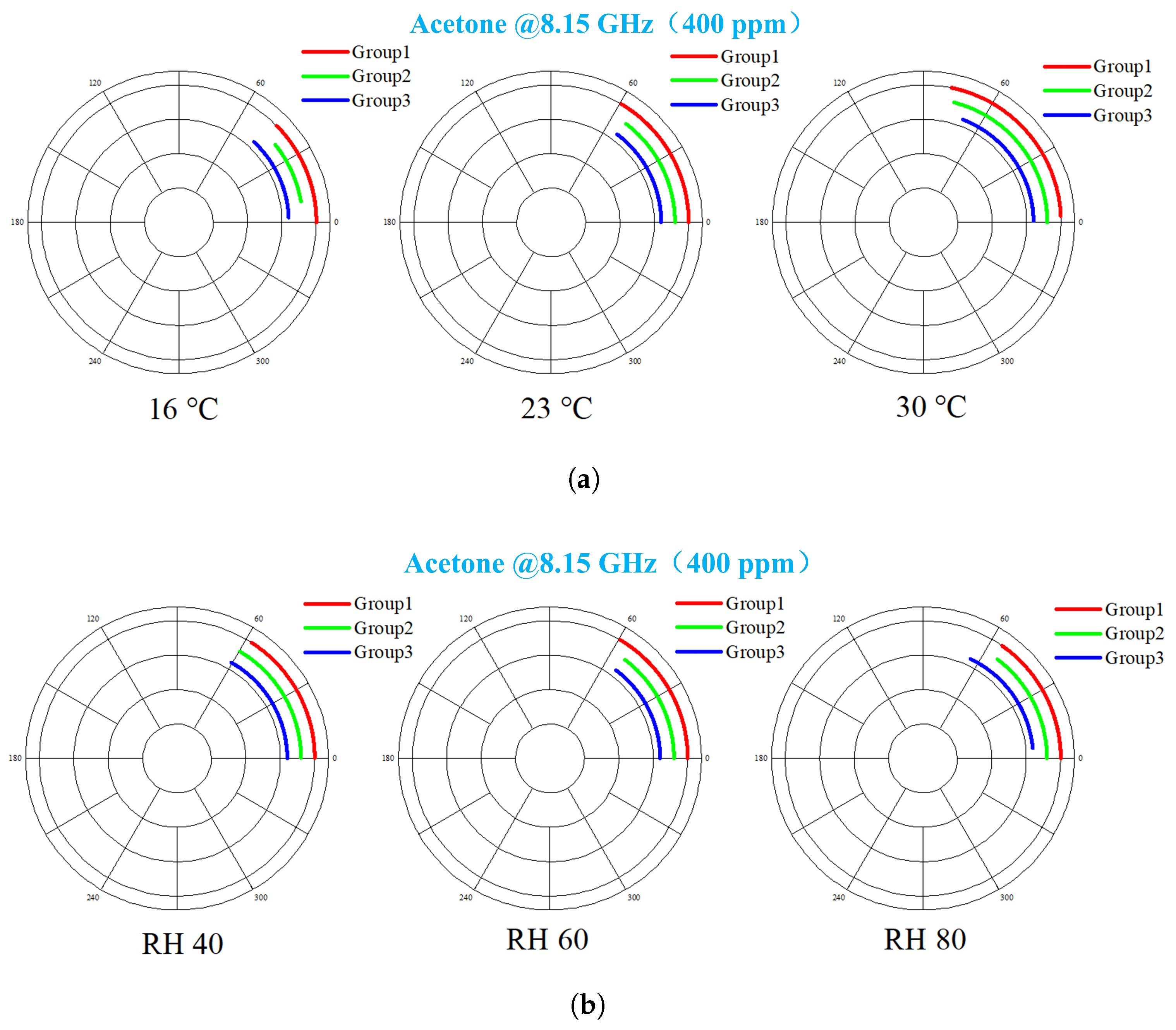

4.3. Temperature and Humidity Effects

4.4. Work Comparison

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| RCR | Rectangular Cavity Resonators |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

| VNA | Vector Network Analyzer |

| CPW | Coplanar Waveguide |

| REF | Reference |

| DUT | Device Under Test |

| SIW | Substrate-Integrated Waveguide |

| RECR | Re-entrant Cavity Resonator |

| TE | Transverse Electric |

| PD | Power Divider |

| RC | Rat-race Coupler |

| MFC | Mass Flow Controller |

| DAQ | Data Acquisition |

| SRR | Split-Ring Resonators |

| METGH | Metal Grid Holes |

References

- Amann, M.; Lutz, M. The revision of the air quality legislation in the European Union related to ground-level ozone. J. Hazard. Mater. 2000, 78, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucur, E.; Necsulescu, C.; Ionita, L.; Nicolescu, I. Survey, emission and evaluation of volatile organic chemicals. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2008, 9, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Zhang, C.; Geng, C.; Hao, L.; Quan, X. Removal of multicomponent VOCs in off-gases from an oil refining wastewater treatment plant by a compost-based biofilter system. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. China 2009, 3, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, T.; Fujimaru, Y.; Minami, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Matsumoto, H.; Sunohara, Y. Characterization of safranal-induced morphological changes and salt stress alleviation in lettuce seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 105, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepanondh, S.; Varoonphan, J.; Sarutichart, P.; Makkasap, T. Airborne Volatile Organic Compounds and Their Potential Health Impact on the Vicinity of Petrochemical Industrial Complex. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011, 214, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, A.; Costello, B.d.L.; Miekisch, W.; Schubert, J.; Buszewski, B.; Pleil, J.; Ratcliffe, N.; Risby, T. The human volatilome: Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in exhaled breath, skin emanations, urine, feces and saliva. J. Breath Res. 2014, 8, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Nie, L.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Hao, Z. Characterization and assessment of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emissions from typical industries. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, F.M.; Pilinis, C.; Seinfeld, J.H. Ozone and aerosol productivity of reactive organics. Atmos. Environ. 1995, 29, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.M.; Xia, Q.; Lu, X.; Huang, J.; Joo, S.W. Synthesis of Indium Oxide Octahedrons for Detection of Toxic Volatile Organic Vapors. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 17691–17697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveesh, S.; Yadav, V.K.S.; Daniel, T.T.; Paily, R. CuO Single-Nanowire Printed Devices for Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) Detection. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2023, 22, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimba, V.; Meghana, N.; Nayak, J. Enhanced room temperature formaldehyde gas sensing properties of hydrothermally synthesized WO3/TiO2 hetero-nanostructures. J. Mater. Res. 2025, 40, 2272–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, B.M.; Gilman, J.B.; Aikin, K.C.; Atlas, E.L.; Goldan, P.D.; Graus, M.; Hendershot, R.; Isaacman-VanWertz, G.A.; Koss, A.; Kuster, W.C.; et al. An improved, automated whole air sampler and gas chromatography mass spectrometry analysis system for volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2017, 10, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Lang, Z.; He, Y.; Zhi, X.; Ma, Y. Calibration-free measurement of absolute gas concentration and temperature via light-induced thermoelastic spectroscopy. Adv. Photonics 2025, 7, 066007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Ji, C.; Tan, J.; Du, B.; Zhao, X.; Yu, J.; Man, B.; Xu, K.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z. Ferroelectrically modulate the Fermi level of graphene oxide to enhance SERS response. Opto-Electron. Adv. 2023, 6, 230094-1–230094-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Z.; Borodinov, N.; Shao, Y.; Luzinov, I.; Yu, G.; Wang, P. Multi-Frequency Measurement of Volatile Organic Compounds With a Radio-Frequency Interferometer. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 3323–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Huang, J.; Ran, Z.; Dai, J.; Dai, Q.; Xie, Y. Injection-Locked-Oscillation-Based Active Sensor on Folded SIW Dual Re-Entrant Cavities Resonator for High-Resolution Detection to VOC Concentration. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 8001311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Stewart, K.; Mansour, R.; Penlidis, A. Polymeric sensing material-based selectivity-enhanced RF resonant cavity sensor for volatile organic compound (VOC) detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 17–22 May 2015; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Tomer, V.K.; Duhan, S. Ordered mesoporous Ag-doped TiO2/SnO2 nanocomposite based highly sensitive and selective VOC sensors (vol 4, pg 1033, 2016). J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 20189–20190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, Y.Y.; Do, J.S.; Li, J. Highly sensitive room temperature ammonia gas sensor based on Ir-doped Pt porous ceramic electrodes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 390, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.; Huang, J. A PDMS-Assisted Back-to-Back SIW Re-Entrant Cavity Microwave Resonator Film for VOC Gas Detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 27231–27241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarifi, M.H.; Fayaz, M.; Goldthorp, J.; Abdolrazzaghi, M.; Hashisho, Z.; Daneshmand, M. Microbead-assisted high resolution microwave planar ring resonator for organic-vapor sensing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 062903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahoumina, P.; Hallil, H.; Lachaud, J.L.; Abdelghani, A.; Frigui, K.; Bila, S.; Baillargeat, D.; Ravichandran, A.; Coquet, P.; Paragua, C.; et al. Microwave flexible gas sensor based on polymer multi wall carbon nanotubes sensitive layer. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 249, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksanyan, M.; Sayunts, A.; Shahkhatuni, G.; Simonyan, Z.; Kananov, D.; Papovyan, R.; Kopecky, D. Influence of the Growth Parameters on RF-Sputtered CNTs and Their Temperature-Selective Application in Gas Sensors. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 34733–34746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandu, D.S.; Nagini, K.B.S.S.; Barik, R.K.; Koziel, S. Highly Sensitive Microwave Sensors Based on Open Complementary Square Split-Ring Resonator for Sensing Liquid Materials. Sensors 2024, 24, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehning, K.J.; Hitzemann, M.; Zimmermann, S. Split-ring resonator with interdigital Split electrodes as detector for liquid and ion chromatography. Sens.-Bio-Sens. Res. 2024, 44, 100645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, P.; Houngkamhang, N.; Orankitanun, T.; Phasukkit, P. Metamaterial Microwave Sensor for Glucose Level Measurement Based on Strip Line with Complementary Split Ring Resonator. Phys. Status Solidi A-Appl. Mater. Sci. 2025, 222, 2400180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buragohain, A.; Das, G.S.; Beria, Y.; Al-Gburi, A.J.A.; Kalita, P.P.; Doloi, T. Highly sensitive differential Hexagonal Split Ring Resonator sensor for material characterization. Sens. Actuators A-Phys. 2023, 363, 114704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xiang, Y. Injection-Locked-Oscillation-Based Active Sensor on Dual-Mode Folded SIW Rectangular Cavity for High-Resolution Detection to Moisture and Fe Particle in Lubricant Oil. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2023, 71, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Huang, J.; Fu, L.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yue, H.; Zhao, Q.; Gu, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. A Novel Differential Capacitive Humidity Sensor on SIW Re-Entrant Cavity Microwave Resonators With PEDOT:PSS Film. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 6576–6585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirkabiri, A.; Idoko, D.; Bridges, G.E.; Kordi, B. Contactless Air-Filled Substrate-Integrated Waveguide (CLAF-SIW) Resonator for Wireless Passive Temperature Sensing. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2022, 70, 3724–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Chu, Q.X.; Xiao, M.Z.; Chen, F.C.; Huang, X.Q.; He, X. Complex Permittivity Measurement Utilizing Multiple Modes of a Rectangular Cavity. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 6000308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.U.; Lim, S. Review of reconfigurable substrate-integrated-waveguide antennas. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 2014, 28, 1815–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Hu, S.; Yue, H.; Zhao, Q.; Ye, F.; Liu, X.; Shen, A.; Zhu, S. Oscillation-Based Active Sensor on SIW Reentrant Cavity Resonator for Self-Sustained Ultralow Concentration Detection to Saline Solution. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2024, 72, 5406–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engen, G. 6-port reflectometer—Alternative network analyzer. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 1977, 25, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegowski, B.; Koelpin, A. Multilayer substrate integrated waveguide six-port junctions with embedded resistive films. Int. J. Microw. Wirel. Technol. 2025, 17, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, A.; Osth, J.; Owais.; Karlsson, M.; Gong, S.; Haartsen, J.; Karlsson, P. Six-port transceiver for 6–9 GHz ultrawideband systems. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2010, 52, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, K.; Huang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhu, S. Sensitivity-Enhanced Multiport-Network-Based Sensor for Moisture Detection in Lubricant Oil. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2025, 73, 2739–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzo-Cabrera, J.; Pedreno-Molina, J.L.; Lozano-Guerrero, A.; Toledo-Moreo, A. A Novel Design of a Robust Ten-Port Microwave Reflectometer With Autonomous Calibration by Using Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2008, 56, 2972–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszek, K.; Rydosz, A.; Maciak, E.; Wincza, K.; Gruszczynski, S. Six-port microwave system for volatile organic compounds detection. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 245, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, P.; Wu, K. Full-Range CSRR-Based Angular Displacement Sensing With Multiport Interferometric Platform. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2021, 69, 4813–4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszek, K.; Piekarz, I.; Sorocki, J.; Koryciak, S.; Wincza, K.; Gruszczynski, S. Low-Cost Microwave Vector System for Liquid Properties Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, J. A Tunable Interferometer for High Sensitivity and Resolution Humidity Sensing. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 2734–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Para. | Description | Value (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Ls | Substrate length | 29 |

| Ws | Substrate width | 26 |

| Hs | Substrate thickness | 0.8 |

| Rs | Inlet and outlet holes | 0.8 |

| Sv | Metallic via spacing | 1.35 |

| Dv | Metallic via size | 0.45 |

| Ra | Radius of retention area | 8 |

| Rp | PDMS loading area radius | 2 |

| Wd | CPW width | 0.25 |

| Lv | Length of cavity | 17.4 |

| Wv | Cavity width | 16.3 |

| Acetone | Ethanol | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Flow: 300 mL/min | Total Flow: 600 mL/min | ||

| Ratio | Conc. (ppm) | Ratio | Conc. (ppm) |

| 5:0 | 2000 | 6:0 | 900 |

| 4:1 | 1300 | 5:1 | 700 |

| 3:2 | 600 | 4:2 | 550 |

| 2:3 | 400 | 3:3 | 350 |

| 1:4 | 300 | 2:4 | 200 |

| Ref. | Working Environment | Sensitive Materials | Detection Limit (ppm) | Environmental Robustness | Portable Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | 100 °C | Agup | 15.4 (acetone) | No | No |

| [15] | RT | PGMA/POEGM | 270 (acetone) 600 (ethanol) | No | No |

| [39] | RT | Comb polymer Pc-based thin film | 0.5 (acetone) | No | Yes |

| [17] | RT | Customized P25DMA | 625 (acetone) | No | No |

| T.W. | RT | PDMS | 300 (acetone) 200 (ethanol) | Yes | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Huang, J. A Multiport Network-Based Integrated Sensing System Using Rectangular Cavity Resonators for Volatile Organic Compounds. Sensors 2026, 26, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010189

Wang H, Huang J. A Multiport Network-Based Integrated Sensing System Using Rectangular Cavity Resonators for Volatile Organic Compounds. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010189

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Haoxiang, and Jie Huang. 2026. "A Multiport Network-Based Integrated Sensing System Using Rectangular Cavity Resonators for Volatile Organic Compounds" Sensors 26, no. 1: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010189

APA StyleWang, H., & Huang, J. (2026). A Multiport Network-Based Integrated Sensing System Using Rectangular Cavity Resonators for Volatile Organic Compounds. Sensors, 26(1), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010189