4.1. Complex Task

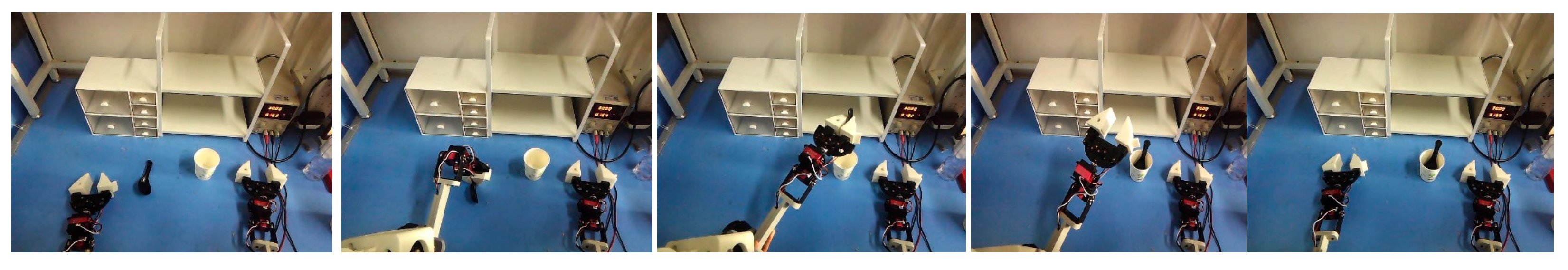

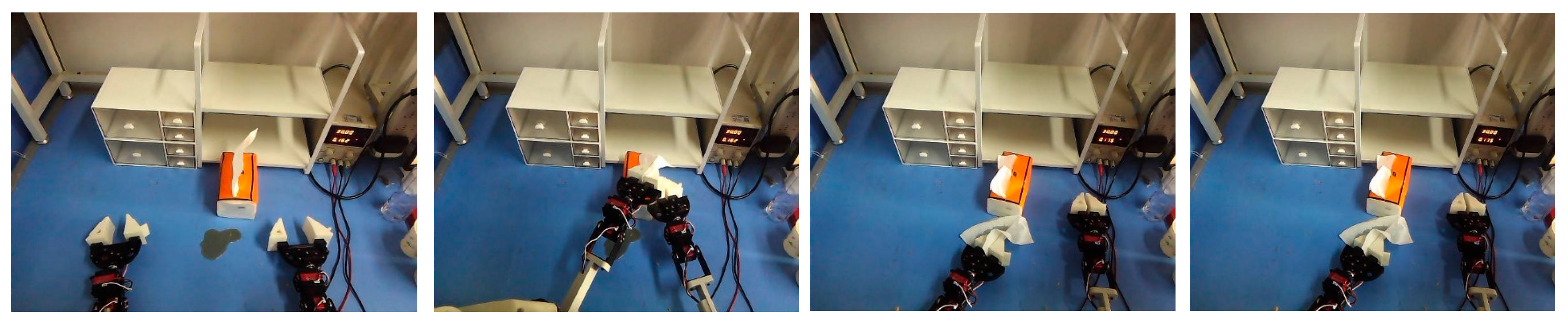

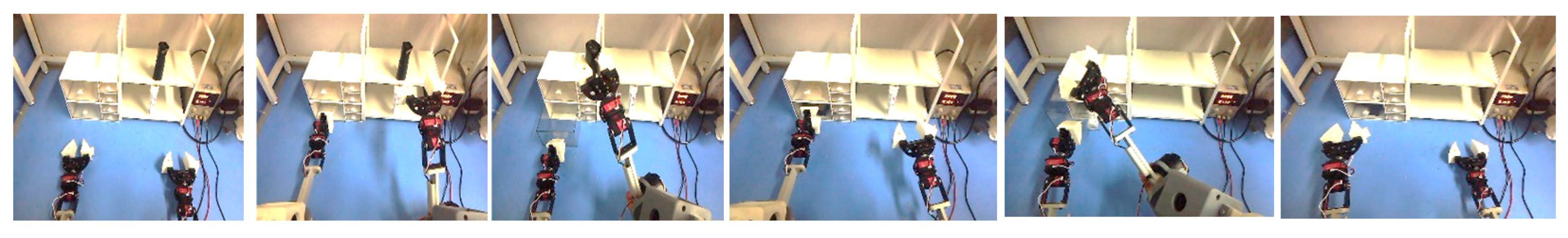

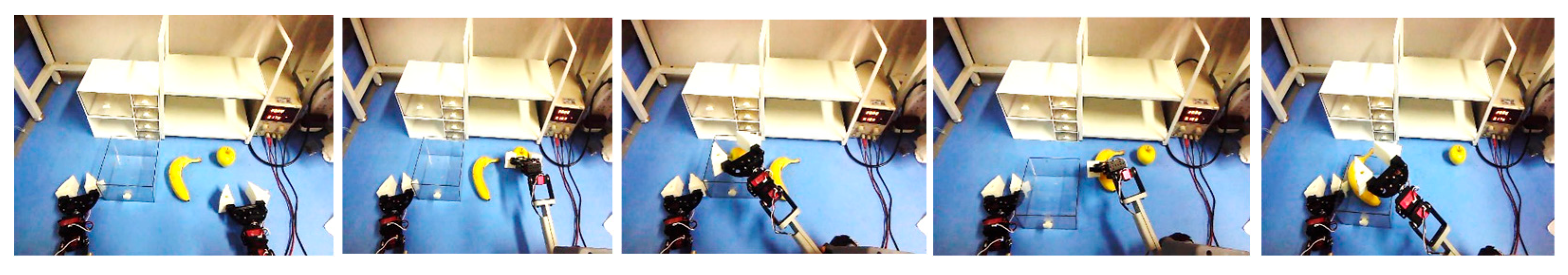

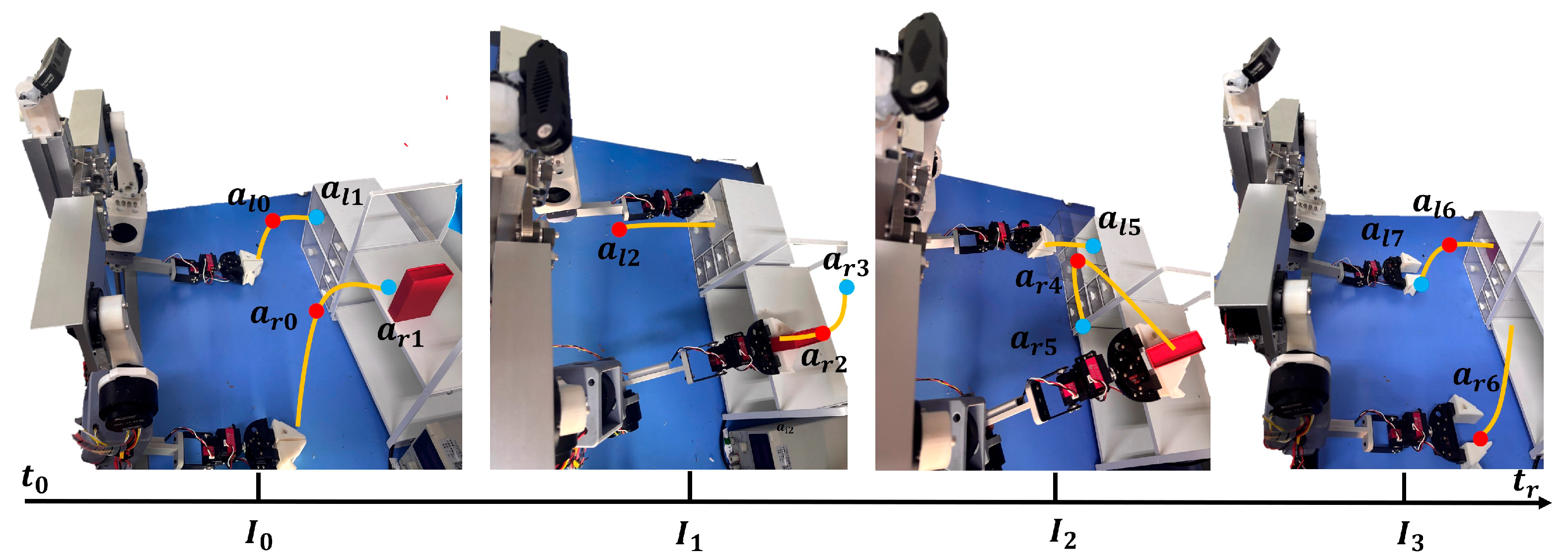

To systematically evaluate the generalization ability and execution accuracy of the proposed VLA model on complex, multi-stage dual-arm manipulation tasks, we designed and selected seven common and challenging robotic tasks that could cover multiple types of object manipulation, spatial coordination, and cross-modal information fusion. Each task required the cooperation of two manipulators and high demands on language understanding, spatial perception, and fine control. These tasks included placing objects, opening and closing drawers, grasping targets, liquid dumping, and container operation, shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. The descriptions of task segmentations were as follows:

- (1)

“Put the red square into the drawer.” The shelf has two layers; the red square is randomly placed on the first or second shelf. (subtask #1) The left arm opens the drawer (subtask #2), the right arm locates the red square and grabs it (subtask #3), the right mechanical claw places the square into the drawer (subtask #4), and the left arm closes the drawer.

- (2)

“Pour the water from the bottle into the cup.” There is a bottle full of water in front of you, and an empty paper cup. (subtask #1) Right arm looks for and grabs the bottle with water in it (subtask #2), picks up the water bottle and approaches the paper cup (subtask #3), evenly pours the water from the cup into the paper cup (subtask #4), and right arm puts the cup back in place after pouring the water.

- (3)

“Put a spoon into a cup,” with a spoon in front of an empty paper cup. Only one spoon can be placed in the cup (subtask #1). The left arm locates the spoon and grasps it (subtask #2). It stops over the mouth of the cup without any error (subtask #3), puts the spoon into the cup, and raises and draws back the arm (subtask #4).

- (4)

“Wipe the table with paper towels.” There is a paper towel on the table with a random, irregular stain. When pumping the paper towel, both arms need to stay close together to prevent the paper towel from being lifted. (Subtask #1) The left arm looks for the tissue and holds it, while the right hand presses the paper bag (subtask #2). The left arm removes the tissue and moves to the stained area, and the right hand returns to its original position (subtask #3). Left arm repeatedly wipes the stained area until it is clean.

- (5)

“Put garbage bags and drugs into different drawers”. There are drugs on the first shelf layer, and garbage bags on the second. (Subtask #1) The left arm locates and grasps the drawer handle on the first floor with the, and the right arm is raised to the position where the garbage bag can be grasped. (Subtask #2) The left arm opens the drawer and keeps it open. The right arm picks up the trash bag and brings it to the top of the first drawer layer. (Subtask #3) After the right arm places the garbage bag in the middle of the drawer, it locates the medicine. (Subtask #4) Robot locates the top drawer on the left, then grabs the medicine with the robot’s right arm. (Subtask #5) It pulls the drawer open with the left arm, lifts the right arm to the top of the drawer, and places it in the middle. (Subtask #6) The left arm closes the drawer, and the right arm returns to the initial position.

- (6)

“Put the specified fruit into the box”. There are boxes on the left side of the table, and bananas and apples on the right. (Subtask #1) The right arm is instructed to choose whether to grab an apple or a banana. (Subtask #2) The right arm places the specified fruit into the box.

- (7)

“Store bowls, chopsticks, and spoons in shelves and drawers”. Bowls with chopsticks and spoons inside are placed on the table. (Subtask #1) Robot positions the left arm and grabs the handle of the first drawer. (Subtask #2) Robot opens the drawer with the left arm and keeps it open. It positions the right arm above the chopstick and grabs it. (Subtask #3) It puts the chopsticks on the top shelf with the right arm. (Subtask #4) Then it moves the right arm over the spoon in the bowl. The spoon is easy to move in the bowl, so it needs to be grasped slowly. (Subtask #5) After picking up the spoon with its right arm, the robot moves it to the top of the drawer. (Subtask #6) The right arm needs to accurately place the spoon into the drawer and withdraw the right arm. (Subtask #7) Robot closes the drawer with the left arm, moves the right arm to the position where the bowl can be grasped, and grasps the bowl. (Subtask #8) The left arm closes the drawer, withdraws, and returns to the initial position, and the right arm picks up the bowl and delivers it to the first position on the shelf. (Subtask #9) The right arm releases the mechanical claw to lower the bowl and then withdraws to the initial position.

Figure 6.

Task 2: pour water.

Figure 6.

Task 2: pour water.

Figure 7.

Task 3: spoon into cup.

Figure 7.

Task 3: spoon into cup.

Figure 8.

Task 4: surface cleaning.

Figure 8.

Task 4: surface cleaning.

Figure 9.

Task 5: classified storage of materials.

Figure 9.

Task 5: classified storage of materials.

Figure 10.

Task 6: sorting fruit.

Figure 10.

Task 6: sorting fruit.

Figure 11.

Task 7: arrangement and placement of utensils.

Figure 11.

Task 7: arrangement and placement of utensils.

4.2. Comparison of Experimental Results

In this paper, we compared the proposed method with three mainstream baseline methods—RDT [

33], OpenVLA [

34], and Aloha [

35]. Our model was trained in a PyTorch Version 2.1.0 environment with an 8 GB NVIDIA RTX 4060 graphics card. We increased the model parameter size to 500 MB and the pre-trained model size to 122 MB.

Then, we applied the pre-trained model to our model for 10,000 iterations. Pretrained large language model batch size is 512, MemVLA model batch size is 1024, Optimizer: AdamW, pretrained large language model learning rate is 1 × 10−4, MemVLA model learning rate is 1 × 10−3, dimension size is 1024. The MemVLA model loss function is L1loss.

We adopted the success rate as the main metric, defined as the number of successful trials divided by the total number of trials. Each scenario was tested 25 times. To understand the model’s capability boundaries and error types during actual execution, we decomposed each task into multiple operational sub-stages and analyzed the model’s performance on these key sub-stages. This evaluation method not only focused on the overall task’s success but also emphasized fine-grained decision-making throughout the process. Specifically, each task typically consists of an object recognition phase, grasp phase, operation or transmission phase, fine interaction stage.

Object recognition phase: Locate the task goal, such as finding the correct drawer, item, or target container. Grasp phase: The manipulator is controlled to reach the target position and complete the firm grasp. Operation or transmission phase: The grasped object is moved to the target position, and the path rationality and attitude are controlled. Fine interaction stage: high-precision interactive actions such as inserting, dumping, and closing the drawer, shown in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7.

To verify the advantages of the proposed lightweight self-attention mechanism in terms of resource efficiency, we systematically compared it with the standard fully connected self-attention method under a completely consistent training environment (including hardware platform, optimizer configuration, batch size, and training data). The evaluation metrics include GPU memory usage and the average time per training round.

The proposed method greatly speeds up training while significantly reducing video memory usage, effectively alleviating the computational and memory bottlenecks of the self-attention mechanism in long-sequence scenarios. As shown in

Table 8, we compare the memory usage and training delay of the two attention mechanisms under the same settings, which verifies the superiority of the lightweight design.

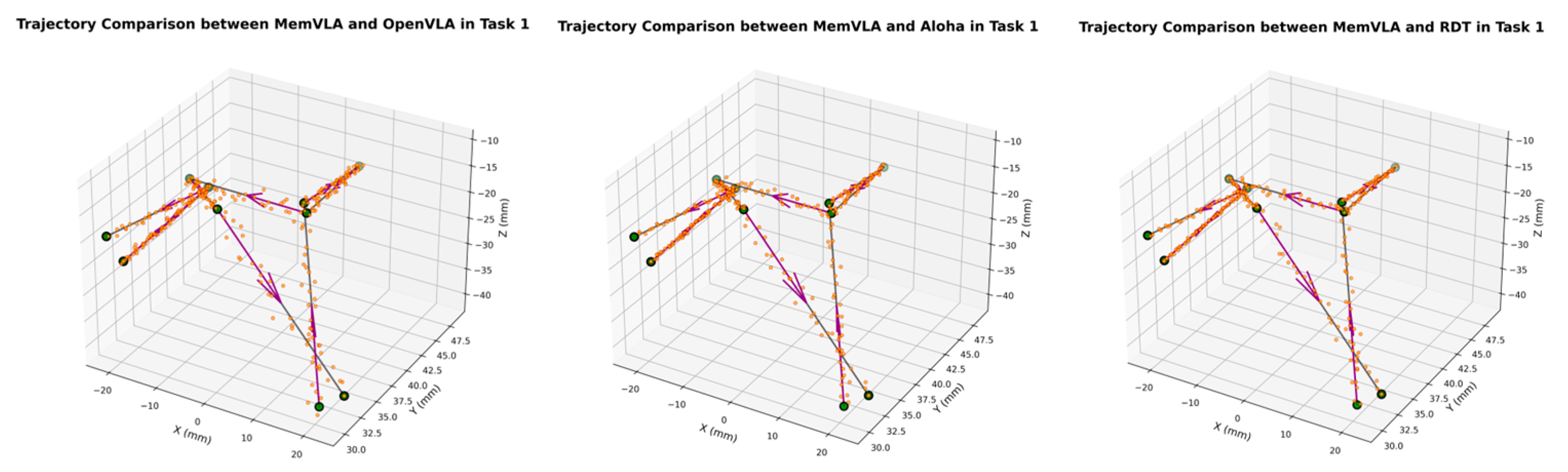

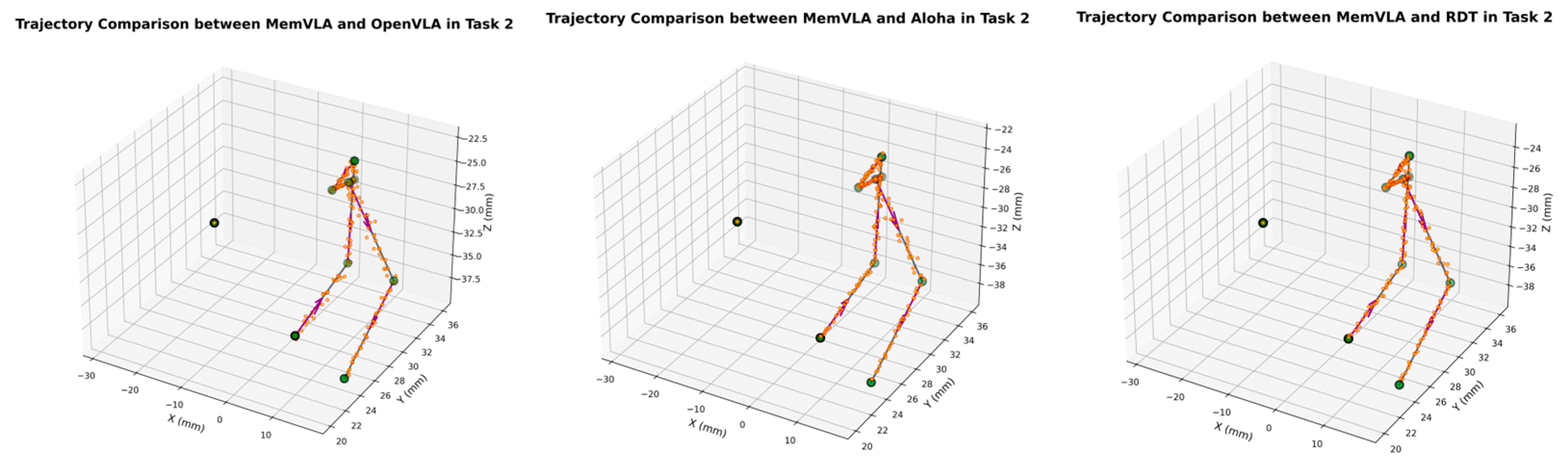

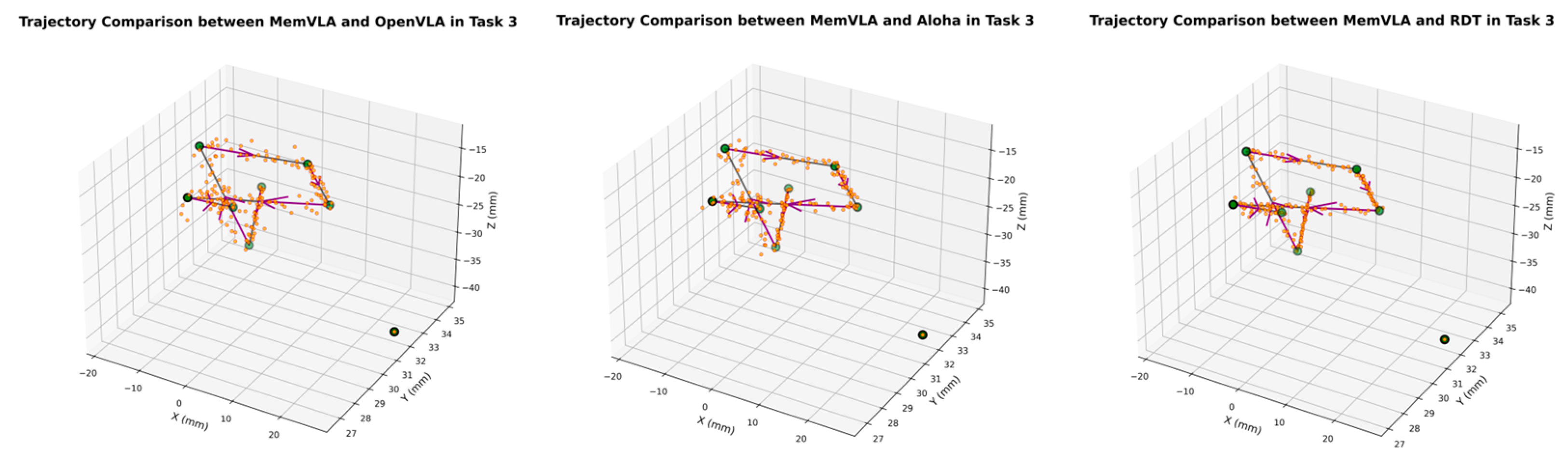

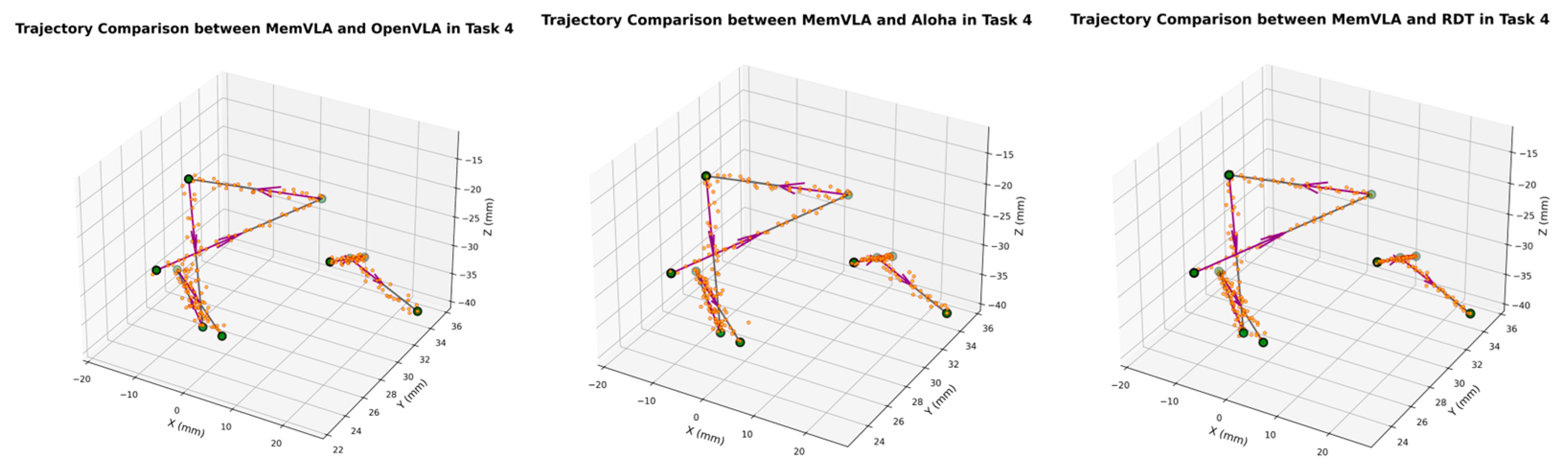

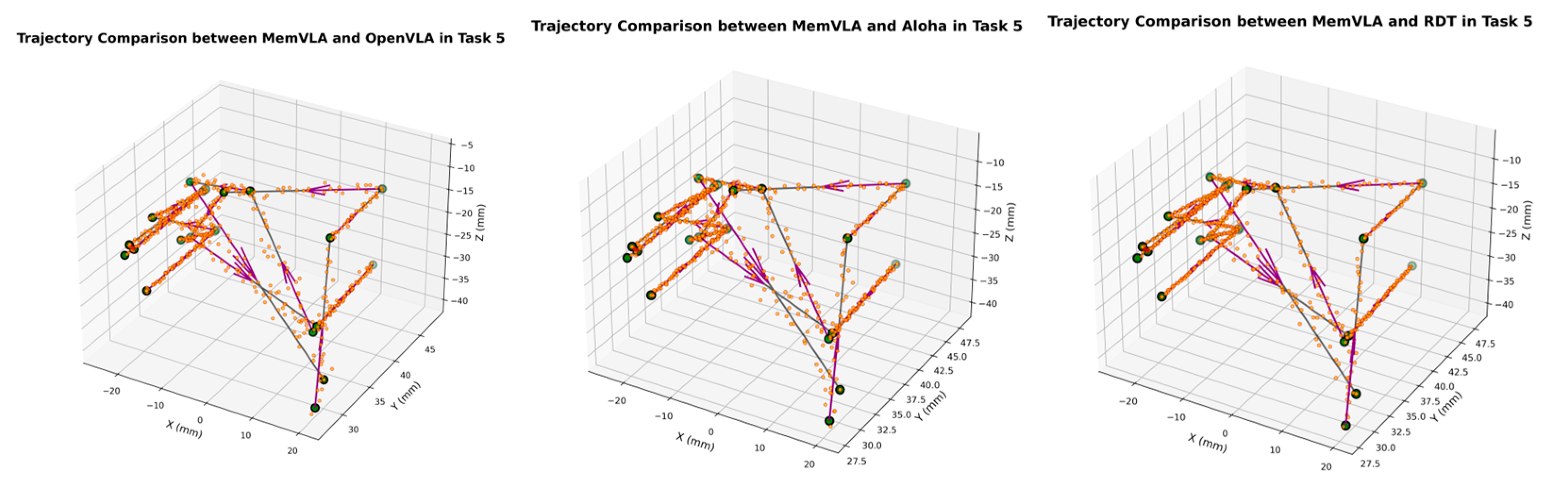

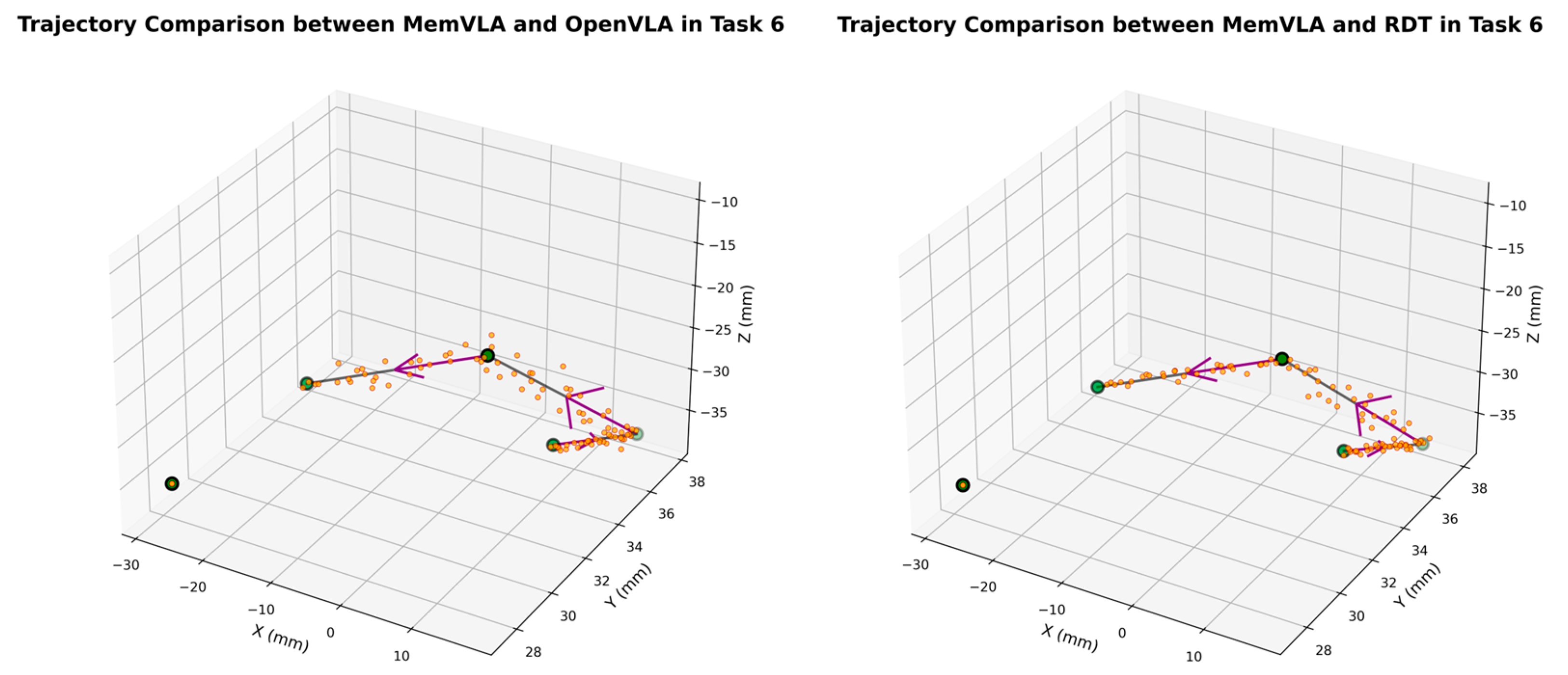

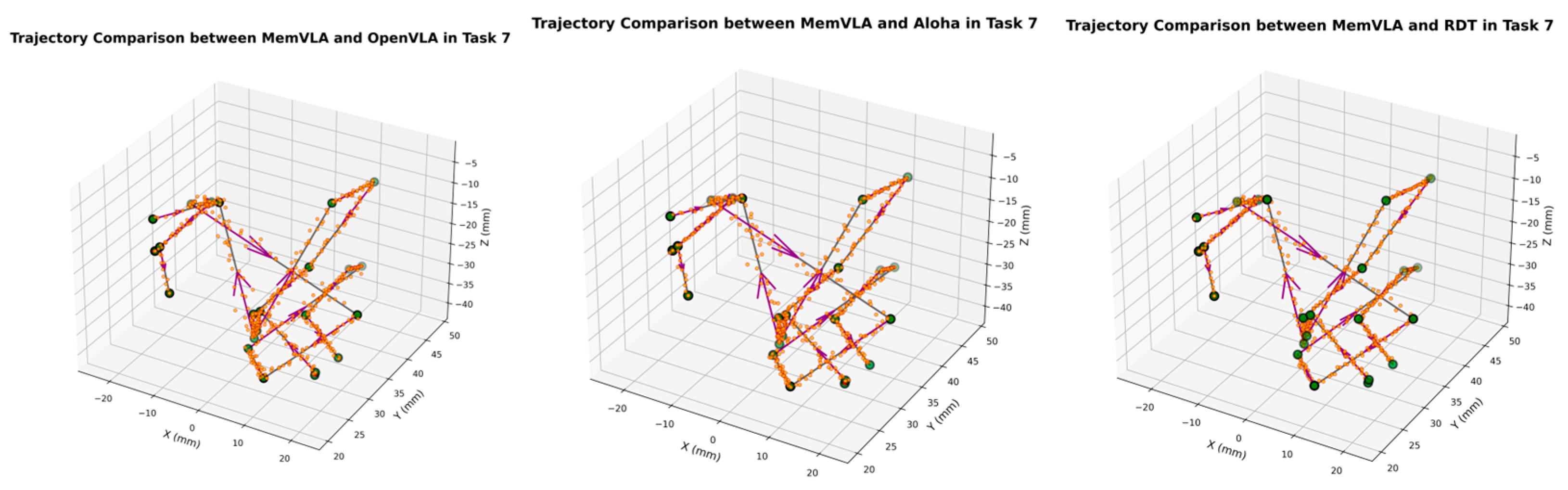

The end-effector trajectory diagrams for the proposed method and other approaches are shown in the following

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18, which compares trajectories from OpenVLA, Aloha, and RDT in sequence. In the figure, the orange endpoints represent the trajectory endpoints output by existing SOTA methods, while the green endpoints denote that output by the proposed method. The solid lines indicate the motion trajectories of the proposed method. It should be noted that, in motor control, we did not perform interpolation; instead, the motors were commanded directly to reach key waypoints, resulting in solid lines. The arrows indicate the direction of the end effector’s gripper movement.

From the above analysis, it can be observed that state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods such as OpenVLA, Aloha, and RDT exhibit significant jitter in robotic arm task execution, with this phenomenon predominantly concentrated between defined key action points. The core of this issue lies in their inherent inference mechanism: analogous to the reasoning logic of large language models, these methods require sequential inference and decision-making for each individual action. Consequently, the generated action sequence struggles to maintain motion continuity. In contrast, the ideal trajectory of a robotic arm should be a smooth straight line or curve; thus, the discretely inferred action points fluctuate around it, leading to considerable trajectory variance.

Delving into the fundamental causes, jitter primarily stems from two core factors: first, the teleoperation bias at the dataset level. If teleoperators fail to skillfully and precisely control the robotic arm via the joystick, the collected action sequence data will inherently contain significant jitter. Subsequent deep learning models, when fitting such flawed data, further amplify this intrinsic defect. Second, the inherent limitations of deep learning itself. Models trained using deep learning can only approximate the collected motion trajectories to within finite error, rather than achieving perfect alignment. This approximation error ultimately manifests as jitter in actual robotic motion.

The MemVLA model introduced targeted improvements to the inference mechanism: the model only needs to infer and generate key action points. During execution, the robotic arm merely requires accurate positioning at these key nodes, while the action sequences between consecutive key points are autonomously executed by the robotic system without additional model inference. This design inherently suppressed robotic arm jitter at the root of the reasoning logic, ensuring smooth trajectories.