FMA-MADDPG: Constrained Multi-Agent Resource Optimization with Channel Prediction in 6G Non-Terrestrial Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Resource Scheduling

2.2. Channel Prediction in Dynamic Wireless Environments

3. Methodology

3.1. System Architecture and Network Model

3.2. Channel Models

3.3. DRL and Training Model for Multi-Agents

3.4. Fusion of Mamba and Attention Model for Channel Prediction

3.5. FMA-MADDPG for Cooperative Scheduling

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Settings

4.2. Performance Comparison of Channel Prediction Models

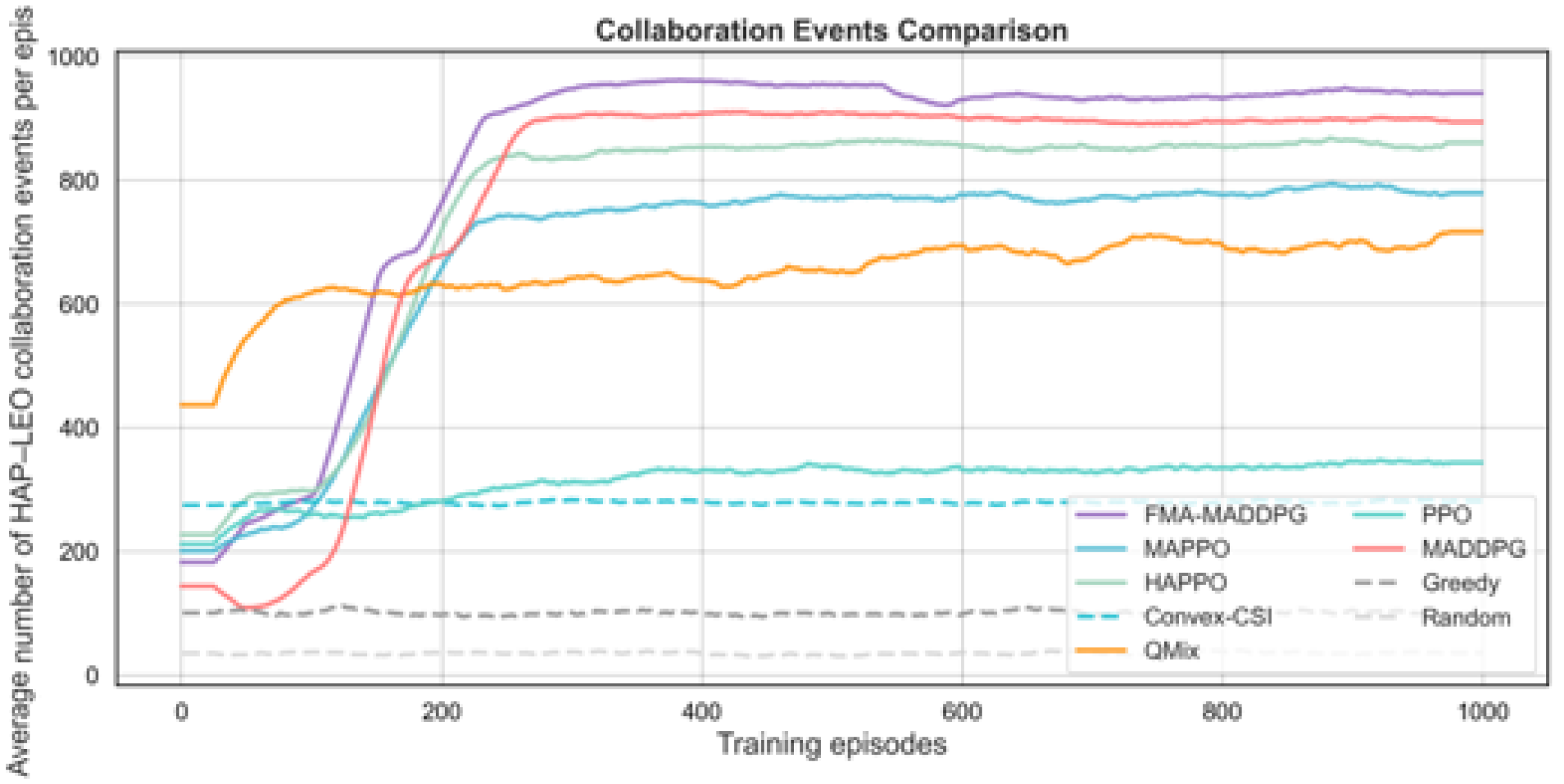

4.3. Comparison with Other Deep Reinforcement Learning Frameworks

4.4. Ablation Study on Prediction and Constraint Design

5. Discussion

5.1. Impact of Channel Prediction on System Performance

5.2. Effectiveness of Reinforcement Learning and Reward Design

5.3. Overall Comparison and System-Level Insights

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Dan, Z. LEO Satellite Navigation Signal Multi-Dimensional Interference Optimisation Method Based on Hybrid Game Theory. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Liu, L.; Zhong, X. Task-Aware Distributed Inter-Layer Topology Optimization Method in Resource-Limited LEO-LEO Satellite Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 3572–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, F.; Song, J.; Han, Z. Resource Allocation and Load Balancing for Beam Hopping Scheduling in Satellite-Terrestrial Communications: A Cooperative Satellite Approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2025, 24, 1339–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, Y.; Kamei, T.; Takahashi, M.; Kato, N.; Miura, A.; Toyoshima, M. Flexible Resource Allocation with Inter-Beam Interference in Satellite Communication Systems with a Digital Channelizer. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 19, 2934–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Jin, Z.; Liu, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Two-Phase Hybrid Optimization for Scheduling Agile Earth Observation Satellites. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Sheng, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Han, Z. Machine Learning-Based Resource Allocation in Satellite Networks Supporting Internet of Remote Things. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 6606–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, P.; Zhou, D. Research on Distributed Collaborative Task Planning and Countermeasure Strategies for Satellites Based on Game Theory Driven Approach. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, S.; Hong, E.-K.; Quek, T.Q.S. Constellation as a Service: Tailored Connectivity Management in Direct-Satellite-to-Device Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2025, 63, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, B.; Li, C.; Ma, J.; Fan, P. Inter-Satellite Links-Enabled Cooperative Edge Computing in Satellite-Terrestrial Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, S.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yin, C.; Quek, T.Q.S. Passive Inter-Satellite Localization Accuracy Optimization in Low Earth Orbit Satellite Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2025, 24, 2894–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, C.; Sheng, M.; Zhou, D.; Shi, Y.; Li, J. Toward Intelligent Cross-Domain Resource Coordinate Scheduling for Satellite Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 9610–9625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Ruan, Y.; Li, Y.; Pan, C.; Elkashlan, M.; Zhang, R.; Li, T. A Hierarchical Game Framework for Win-Win Resource Trading in Cognitive Satellite Terrestrial Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 13530–13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Gao, J.; Zhao, L. Collaborative Multi-Resource Allocation in Terrestrial-Satellite Network Towards 6G. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 7057–7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Wang, J.-B.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Cheng, M.; Lin, M.; Wang, J. Satellite-Terrestrial Assisted Multi-Tier Computing Networks with MIMO Precoding and Computation Optimization. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 3763–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Long, K.; Leung, V.C.M. Joint Optimization of Caching Placement and Power Allocation in Virtualized Satellite-Terrestrial Network. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 7932–7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, R.; Gao, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z. Interference-Suppressed Joint Channel and Power Allocation for Downlinks in Large-Scale Satellite Networks: A Dynamic Hypergraph Neural Network Approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Ma, T.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, L. Service-Aware Resource Orchestration in Ultra-Dense LEO Satellite-Terrestrial Integrated 6G: A Service Function Chain Approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 6003–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, B.; Zhang, H.; Song, L.; Li, Y.; Li, G.Y. Ultra-Dense LEO: Integrating Terrestrial-Satellite Networks Into 5G and Beyond for Data Offloading. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 18, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Wang, J.-B.; Zhang, H.; Lin, M.; Li, G.Y. Joint Optimization of Transmission and Computation Resources for Satellite and High Altitude Platform Assisted Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 1362–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Gao, Z.; Tao, Y. Satellite Beam Slicing Resource Allocation Strategy Based on Business Recognition and Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Computers and Artificial Intelligence Technology (CAIT), Hangzhou, China, 20–22 December 2024; pp. 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yuan, A.; Xiao, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wang, D.; Jiang, H.; Jiao, L. Class Incremental Learning with Few-Shots Based on Linear Programming for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 5474–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, C.; Qian, C.; Wang, W.; Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Yue, C. Research on Intelligent Matching Technology for Natural Disaster Monitoring Needs Based on Multi Satellite and Multi Payload. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Geology, Mapping and Remote Sensing (ICGMRS), Wuhan, China, 12–14 April 2024; pp. 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, G.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.W.; Oh, D. Comparative Analysis on the Resource Allocations for Interference-Limited LEO Satellite Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 11–13 October 2023; pp. 1645–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhu, W.; Zhai, Y.; Yang, M.; Li, H. A Multi-Objective Optimization Based LEO Satellite Beam Hopping Resource Allocation Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 13–16 December 2024; pp. 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C.; Han, Z.; Qin, Z.; Lv, Y. User Position-Driven Resource Allocation for Beam Hopping in Low Earth Orbit Satellite. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Electronic Engineering and Signal Processing (EESP), Derby, UK, 2–4 December 2024; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Song, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Miao, Z. Joint Communication, Computing, and Caching Resource Allocation in LEO Satellite MEC Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 6708–6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Ding, B.; Xiao, Z.; Jiao, L.; Chen, H.; Regan, A.C. Hyperspectral Image Classification Based on Deep Attention Graph Convolutional Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5504316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, G.; Duan, L.; Wu, Q. Multi-Objective Optimization for UAV Swarm-Assisted IoT with Virtual Antenna Arrays. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 4890–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Sun, C. Research on the Application of Artificial Intelligence Technology in Beam Resource Allocation for Multi-Beam Satellite Communication Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA), Hangzhou, China, 25–27 April 2025; pp. 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, K. Edge Computing-Enabled Real-Time Resource Allocation System Based on Satellite Cluster. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 13–16 December 2024; pp. 2128–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Huang, W.; Sun, L.; Cao, H. Resource Optimization in Low Earth Orbit Satellites with Edge Computing: An ADMM-Based Resource Management Strategy. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering (NNICE), Guangzhou, China, 10–12 January 2025; pp. 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, X. SCODA: Joint Optimization of Task Offloading and Resource Allocation in LEO-Assisted MEC System with Satellite Cooperation. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2025, 14, 3304–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Meng, Q.; Wang, G.; Bian, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Satellite Edge Intelligence: DRL-Based Resource Management for Task Inference in LEO-Based Satellite-Ground Collaborative Networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 10710–10728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, R.; Liu, J.; Tang, X.; Gui, K.; Chen, Q. A Hybrid Offline and Online Resource Allocation Algorithm for Multibeam Satellite Communication Systems. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 21, 3711–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Xu, T.; Chen, X.; Zarakovitis, C.C.; Wu, C. Blocked-Job-Offloading-Based Computing Resources Sharing in LEO Satellite Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 2287–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Module | Layer Type | Configuration | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Encoding | Linear + Positional Embedding | ||

| Mamba Backbone | State-Space Block () | Hidden size | |

| MHSA | Multi-Head Self-Attention | , | |

| Fusion | Residual + LayerNorm | Skip connection | |

| Feed-Forward | Two-layer MLP | , GELU | |

| Temporal Pooling | Attention Pooling | Weight vector | |

| Output Head | Linear Projection |

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| , Z | Set and number of ground UEs |

| , H | Set and number of HAPs |

| , L | Set and number of LEO satellites |

| , A | Set and number of sub-areas |

| k, t | Time-slot index in an episode |

| 3D position of a UE at slot k | |

| 3D position of a HAP | |

| Total bandwidth of the UE–HAP uplink | |

| , | Set and number of UE–HAP sub-channels |

| Bandwidth allocated to UE z–HAP h link at slot k | |

| Maximum transmit power of UE z | |

| Transmit power from UE z to HAP h at slot k | |

| Binary UE–HAP association indicator at slot k | |

| Instantaneous SNR on UE z–HAP h link at slot k | |

| Instantaneous rate on UE z–HAP h link at slot k | |

| Cumulative throughput of UE z up to slot k | |

| Jain’s fairness index over all UEs at slot k | |

| End-to-end delay of UE z–HAP h transmission at slot k | |

| Composite system reward at slot k | |

| CSI matrix of UE–HAP links at time t | |

| CSI matrix of HAP–LEO links at time t | |

| Vector of available bandwidths at time t | |

| Vector of available transmit powers at time t | |

| Vector of HAP queue lengths at time t | |

| Global system state at time t | |

| Local observation of agent i at time t | |

| Action of agent i at time t | |

| UE–HAP association decision in agent i’s action | |

| Bandwidth allocation ratio to HAP h in agent i’s action | |

| Transmit power of HAP h in agent i’s action | |

| Total capacity (throughput) at time t | |

| Average end-to-end delay at time t | |

| Jain’s fairness index at time t | |

| Number of collaboration events at time t | |

| Weights of reward components in (13) and (30) | |

| CSI feature vector at time slot t (FMA input) | |

| History window of CSI features used by FMA | |

| L | Length of the CSI history window |

| Prediction horizon (number of slots ahead) | |

| Hidden sequence produced by the Mamba backbone | |

| Feature sequence output by the MHSA block | |

| , | Fused feature sequences before and after feed-forward network |

| Pooled feature vector used for CSI prediction | |

| Predicted future CSI vector at time |

| Deep Reinforcement Learning/Baseline Method | Total Reward | Collaboration Events | System Efficiency | Load Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPO | 1331.1 | 344 | 0.745 | 0.975 |

| MAPPO | 2519.3 | 784 | 0.900 | 0.981 |

| HAPPO | 2789.3 | 858 | 0.891 | 0.985 |

| QMIX | 2465.4 | 701 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| MADDPG | 2749.1 | 897 | 1.012 | 0.997 |

| Convex-CSI | 2812.7 | 282 | 0.879 | 0.920 |

| Greedy | 1974.6 | 100 | 0.718 | 0.825 |

| Random | 1160.8 | 36 | 0.457 | 0.647 |

| FMA-MADDPG (proposed) | 3199.4 | 942 | 1.011 | 0.997 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, C.; Song, K.; Bai, J.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Sun, Y. FMA-MADDPG: Constrained Multi-Agent Resource Optimization with Channel Prediction in 6G Non-Terrestrial Networks. Sensors 2026, 26, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010148

Yang C, Song K, Bai J, Li C, Zhao Y, Xiao Z, Sun Y. FMA-MADDPG: Constrained Multi-Agent Resource Optimization with Channel Prediction in 6G Non-Terrestrial Networks. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010148

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Chunyu, Kejian Song, Jing Bai, Cuixing Li, Yang Zhao, Zhu Xiao, and Yanhong Sun. 2026. "FMA-MADDPG: Constrained Multi-Agent Resource Optimization with Channel Prediction in 6G Non-Terrestrial Networks" Sensors 26, no. 1: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010148

APA StyleYang, C., Song, K., Bai, J., Li, C., Zhao, Y., Xiao, Z., & Sun, Y. (2026). FMA-MADDPG: Constrained Multi-Agent Resource Optimization with Channel Prediction in 6G Non-Terrestrial Networks. Sensors, 26(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010148