Leveraging Central Sleep Apnea Events to Validate the Measurement of Lung Volume Changes Using Thoracic Bio-Impedance

Abstract

1. Introduction

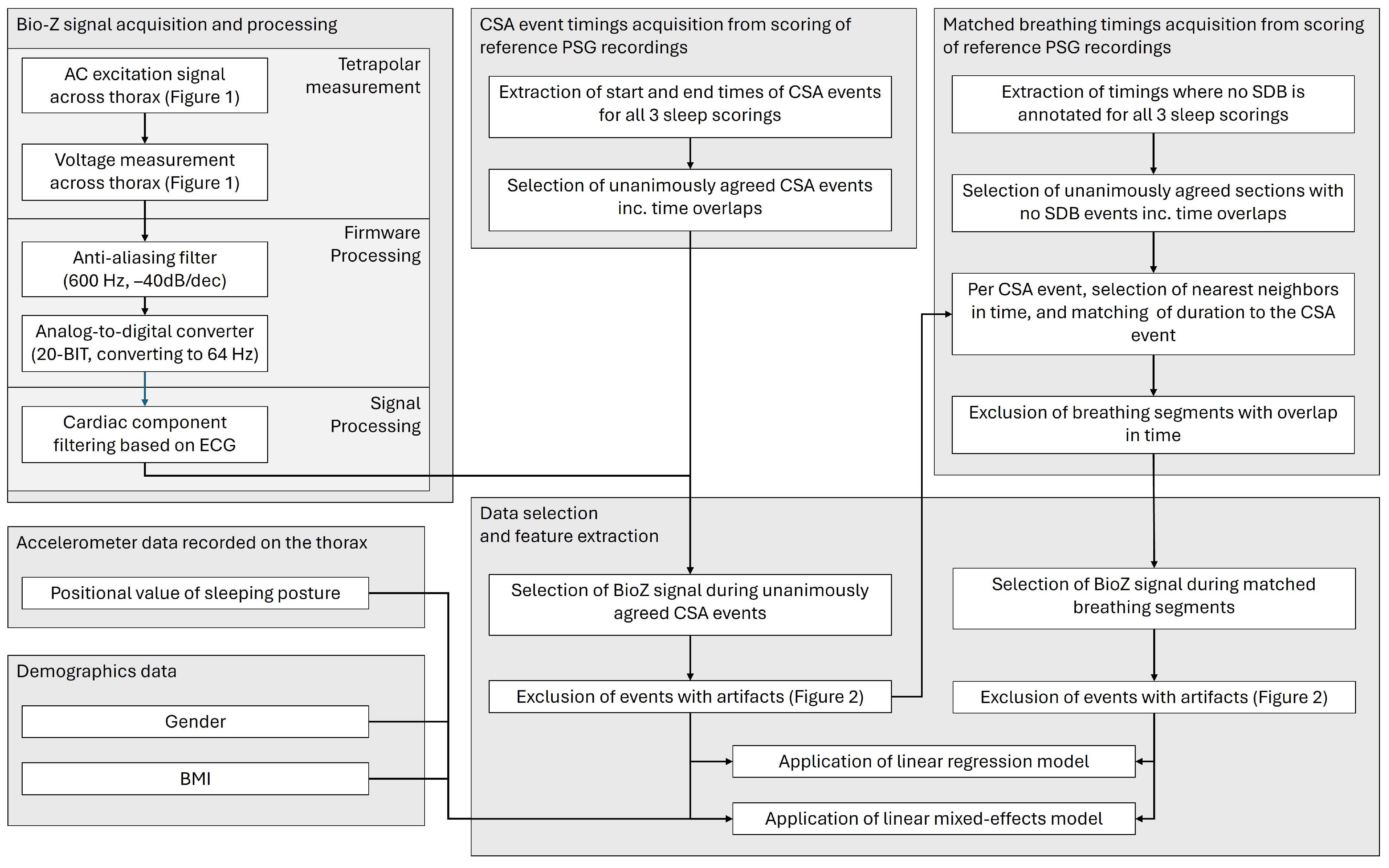

2. Materials and Methods

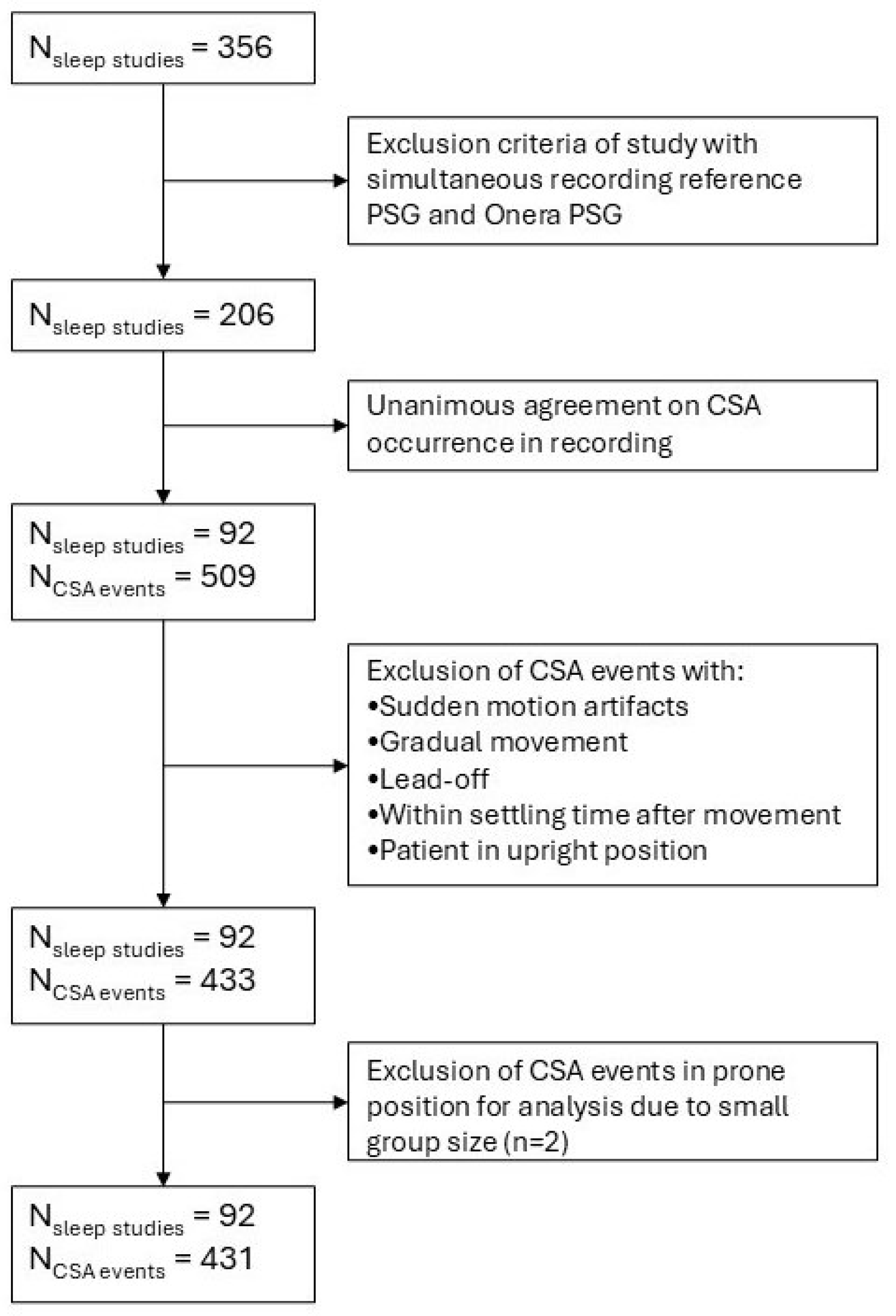

2.1. Study Design and Dataset

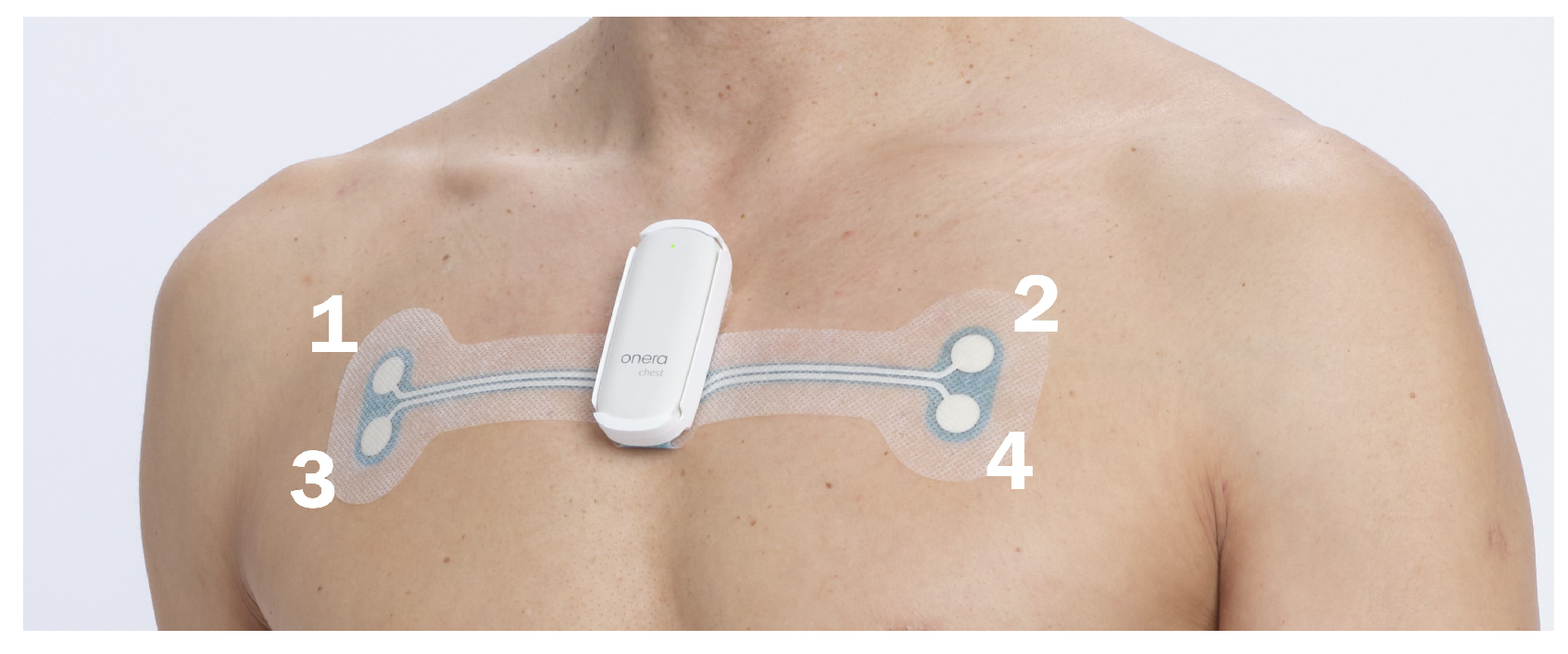

2.2. Bio-Impedance Measurement Device

2.3. Signal Processing and Filtering

- Cardiac component filtering was performed based on the electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings of the patch-based tetrapolar device;

- Segments s were excluded;

- Two seconds were trimmed from the segment edges;

- Segments with sudden motion artifacts (> s) were excluded;

- Segments with gradual movement (> total) were excluded;

- Segments with lead-off sections (loose electrodes) were excluded;

- Segments with sudden movement before the segment to account for settling time of the BioZ (> s in the 10 s before the start of the segment) were excluded;

- Segments where the patient is in an upright position (position value of ) were excluded;

- The interpolation of outliers (> standard deviation) was performed.

2.4. Segment Matching

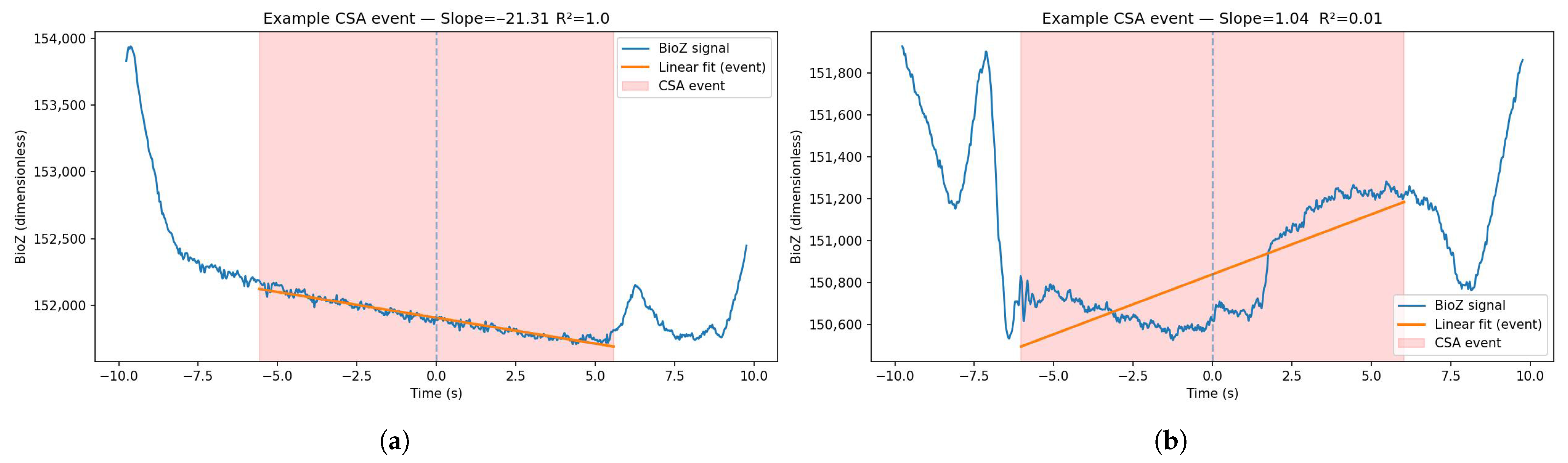

2.5. Feature Extraction

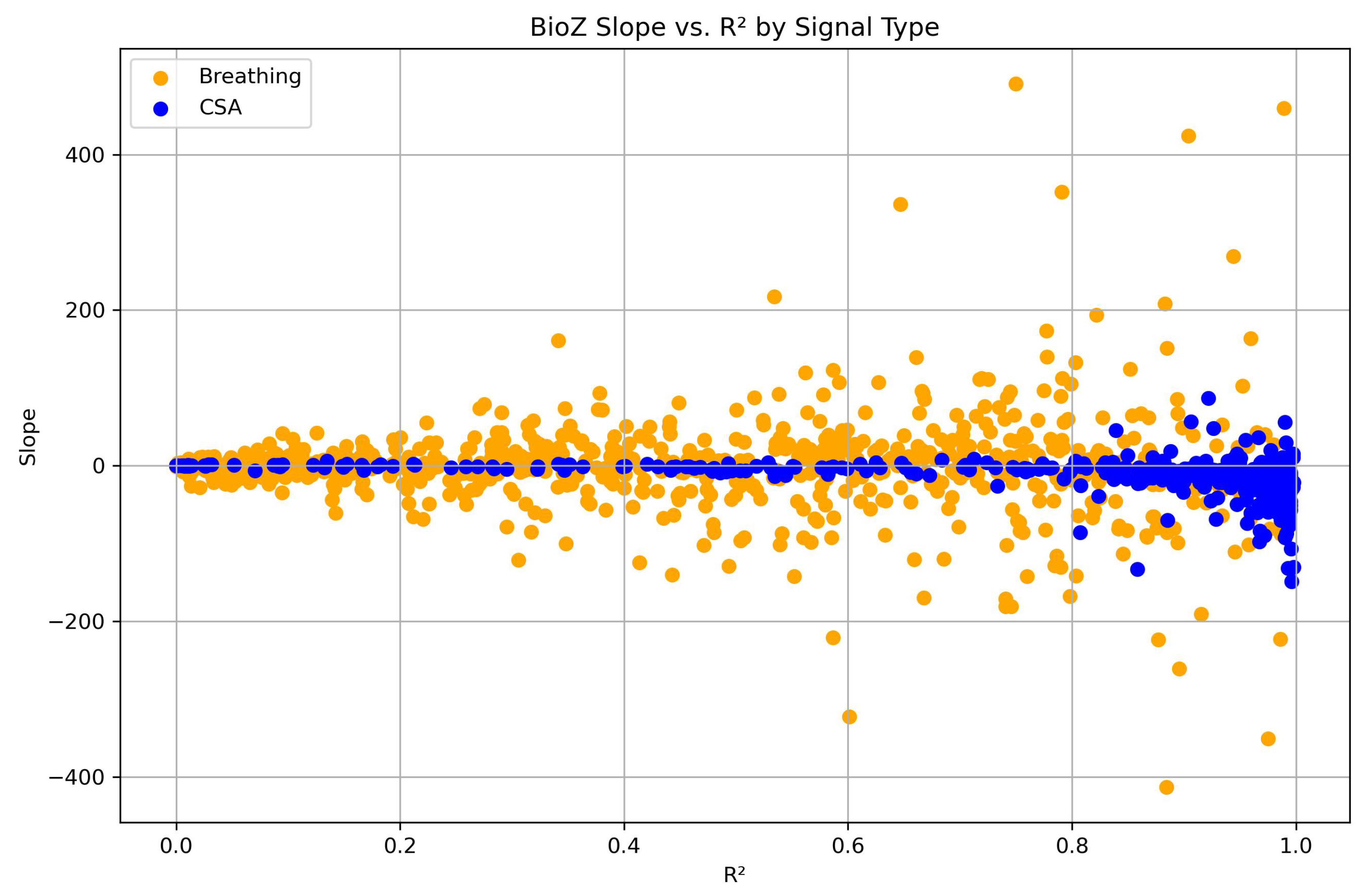

- Baseline slope of the BioZ signal;

- Linearity of that slope (e.g., of linear fit) (Figure 4).

- Prone: – and –;

- Lateral: – and –;

- Supine: –.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Group-Level Analysis

3.2. Mixed-Effects Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BioZ | Bio-impedance; |

| CSA | Central sleep apnea; |

| SDB | Sleep disordered breathing; |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance; |

| BMI | Body mass index; |

| AASM | American Academy of Sleep Medicine; |

| OSA | Obstructive sleep apnea; |

| PSG | Polysomnography; |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram; |

| CI | Confidence interval; |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. |

References

- Berry, R.B.; Albertario, C.L.; Harding, S.M. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, Technical Specifications. Version 2.5; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Safwan Badr, M.; Martin, J.L. Essentials of Sleep Medicine A Practical Approach to Patients with Sleep Complaints, 2nd ed.; Humana Press: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ayappa, I.; Norman, R.G.; Suryadevara, M.; Rapoport, D.M. Comparison of Limited Monitoring Using a Nasal-Cannula Flow Signal to Full Polysomnography in Sleep-Disordered Breathing. Sleep 2004, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retory, Y.; Niedzialkowski, P.; De Picciotto, C.; Bonay, M.; Petitjean, M. New respiratory inductive plethysmography (RIP) method for evaluating ventilatory adaptation during mild physical activities. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazeri, K.; Jonsson, A.; Agustsson, J.S.; Serwatko, M.; Gislason, T.; Arnardottir, E.S. The design of RIP belts impacts the reliability and quality of the measured respiratory signals. Sleep Breath. 2021, 25, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppä, V.P.; Pelkonen, A.S.; Kotaniemi-Syrjänen, A.; Mäkelä, M.J.; Viik, J.; Malmberg, L.P. Tidal breathing flow measurement in awake young children by using impedance pneumography. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 115, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeyersons, J.; Morales, J.; Seeuws, N.; Van Hoof, C.; Hermeling, E.; Groenendaal, W.; Willems, R.; Van Huffel, S.; Varon, C. Artefact detection in impedance pneumography signals: A machine learning approach. Sensors 2021, 21, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, K.P.; Ladd, W.M.; Beams, D.M.; Sheers, W.S.; Radwin, R.G.; Tompkins, W.J.; Webster, J.G.; Fellow, L.; Ladd, W.M. Comparison of Impedance and Inductance Ventilation Sensors on Adults During Breathing, Motion, and Simulated Airway Obstruction. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1997, 44, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppä, V.P.; Hyttinen, J.; Uitto, M.; Chrapek, W.; Viik, J. Novel electrode configuration for highly linear impedance pneumography. Biomed. Technol. 2013, 58, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, M.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Jeong, I.C.; Park, S.B.; Yong, S.J.; Kim, W.K.; Yoon, H.R. Development and evaluation of an improved technique for pulmonary function testing using electrical impedance pneumography intended for the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Sensors 2013, 13, 15846–15860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.B.; Yen, C.W.; Liang, J.T.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G.Z.; Song, R. A Robust Electrode Configuration for Bioimpedance Measurement of Respiration. J. Healthc. Eng. 2014, 5, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppä, V.P.; Viik, J.; Hyttinen, J. Assessment of pulmonary flow using impedance pneumography. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 57, 2277–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Almazán, D.; Groenendaal, W.; Catthoor, F.; Jané, R. Chest Movement and Respiratory Volume both Contribute to Thoracic Bioimpedance during Loaded Breathing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimnes, S.; Grøttem Martinsen, Ø. Bioimpedance and Bioelectricity Basics, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Elke, G.; Pulletz, S.; Schädler, D.; Zick, G.; Gawelczyk, B.; Frerichs, I.; Weiler, N. Measurement of regional pulmonary oxygen uptake—A novel approach using electrical impedance tomography. Physiol. Meas. 2011, 32, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedel, T.; Bürgi, F.; Greif, R.; Kaiser, H.; Riva, T.; Theiler, L.; Nabecker, S. Changes in lung volume estimated by electrical impedance tomography during apnea and high-flow nasal oxygenation: A single-center randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viniol, C.; Galetke, W.; Woehrle, H.; Nilius, G.; Schobel, C.; Randerath, W.; Leiter, J.; Canisius, S.; Schneider, H. Clinical validation of a wireless patch-based polysomnography system. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2025, 21, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seppä, V.P.; Hyttinen, J.; Viik, J. A method for suppressing cardiogenic oscillations in impedance pneumography. Physiol. Meas. 2011, 32, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Positive Slope of BioZ Signal | Negative Slope of BioZ Signal | Total Number of CSA Events/Matched Breathing Segments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breathing segments | 378 (∼48%) | 407 (∼52%) | 785 |

| CSA events | 76 (∼18%) | 357 (∼82%) | 433 |

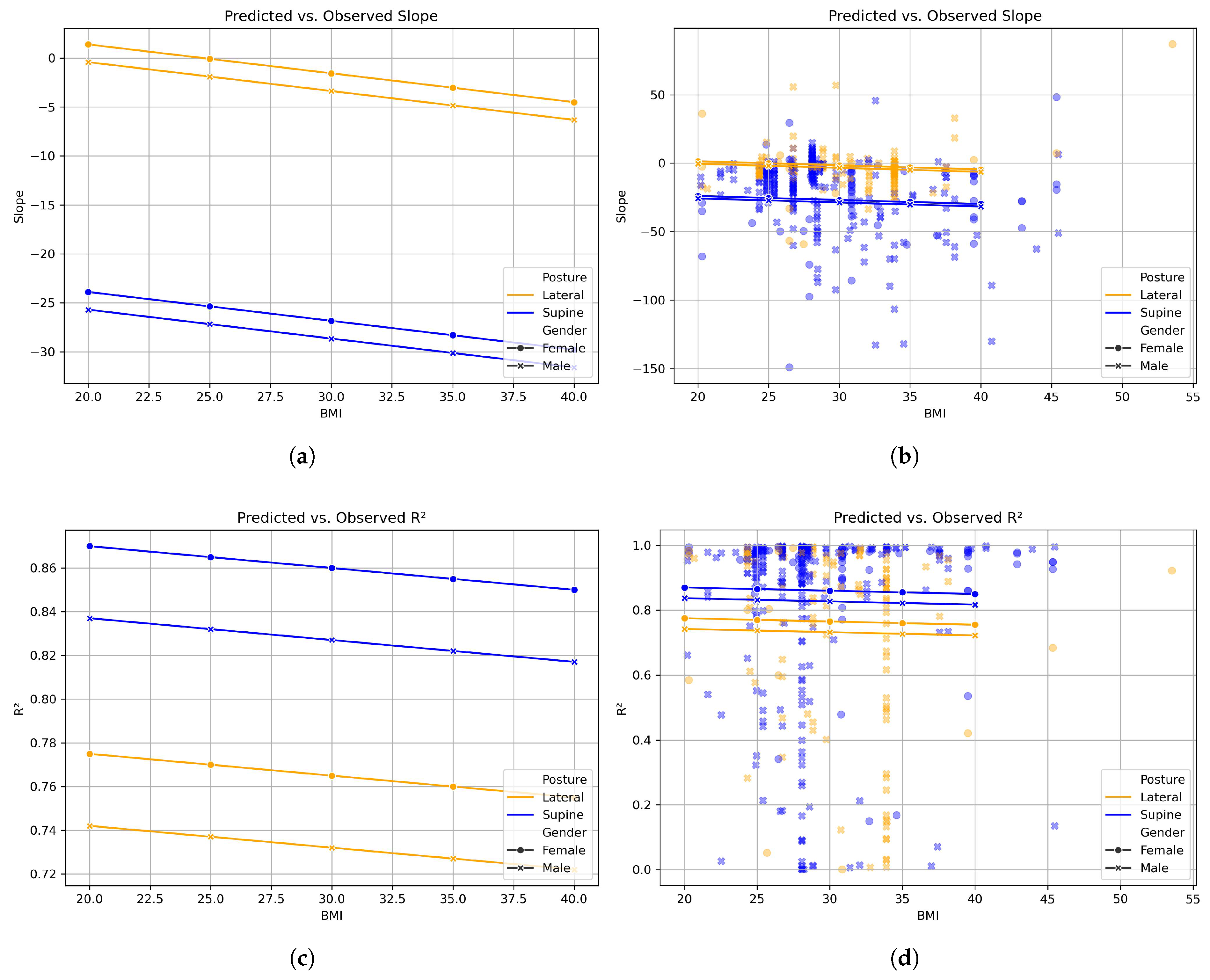

| Predictor | Coef. | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 7.286 | 0.626 | [−21.999, 36.571] |

| Gender [Ref. male] | −1.810 | 0.764 | [−13.632, 10.012] |

| Posture [Ref. supine] | −25.288 | <0.001 | [−30.761, −19.815] |

| BMI | −0.295 | 0.495 | [−1.143, 0.552] |

| Predictor | Coef. | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.795 | 0.000 | [0.573, 1.017] |

| Gender [Ref. male] | −0.033 | 0.453 | [−0.118, 0.053] |

| Posture [Ref. supine] | 0.095 | 0.005 | [0.028, 0.161] |

| BMI | −0.001 | 0.828 | [−0.007, 0.006] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Knoops-Borm, M.A.W.; Vullings, R.; Schneider, H., on behalf of the Home PSG Validation Study Consortium Group; Overeem, S. Leveraging Central Sleep Apnea Events to Validate the Measurement of Lung Volume Changes Using Thoracic Bio-Impedance. Sensors 2026, 26, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010012

Knoops-Borm MAW, Vullings R, Schneider H on behalf of the Home PSG Validation Study Consortium Group, Overeem S. Leveraging Central Sleep Apnea Events to Validate the Measurement of Lung Volume Changes Using Thoracic Bio-Impedance. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnoops-Borm, Martine A. W., Rik Vullings, Hartmut Schneider on behalf of the Home PSG Validation Study Consortium Group, and Sebastiaan Overeem. 2026. "Leveraging Central Sleep Apnea Events to Validate the Measurement of Lung Volume Changes Using Thoracic Bio-Impedance" Sensors 26, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010012

APA StyleKnoops-Borm, M. A. W., Vullings, R., Schneider, H., on behalf of the Home PSG Validation Study Consortium Group, & Overeem, S. (2026). Leveraging Central Sleep Apnea Events to Validate the Measurement of Lung Volume Changes Using Thoracic Bio-Impedance. Sensors, 26(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010012