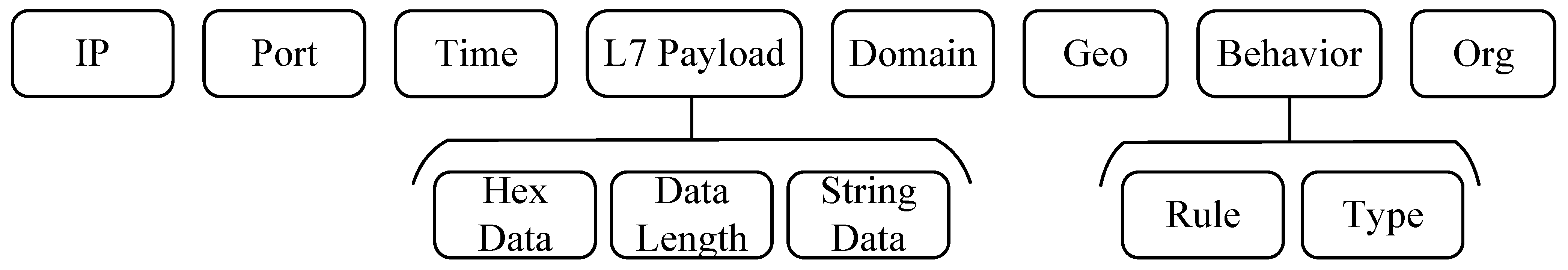

Prior work on cyber bot behavior analysis achieves limited coverage (typically 1–60% on their respective datasets [

18,

21,

22,

38,

57]), precluding comprehensive characterization of cyber bot behaviors at Internet scale. We achieve 83.7% overall coverage (0.8% initially labeled by existing rules, plus 82.9% by our 296 extracted patterns), enabling the systematic analysis presented in this section. We examine cyber bot behaviors across both the initially labeled payloads and the 296 payload patterns extracted in

Section 6.2, exploring the generation principles, identities, techniques, and strategies employed by cyber bots, contributing valuable insights to threat analysis [

10]. In particular, we aim to answer the following research questions:

7.1. Generation Principles (RQ1)

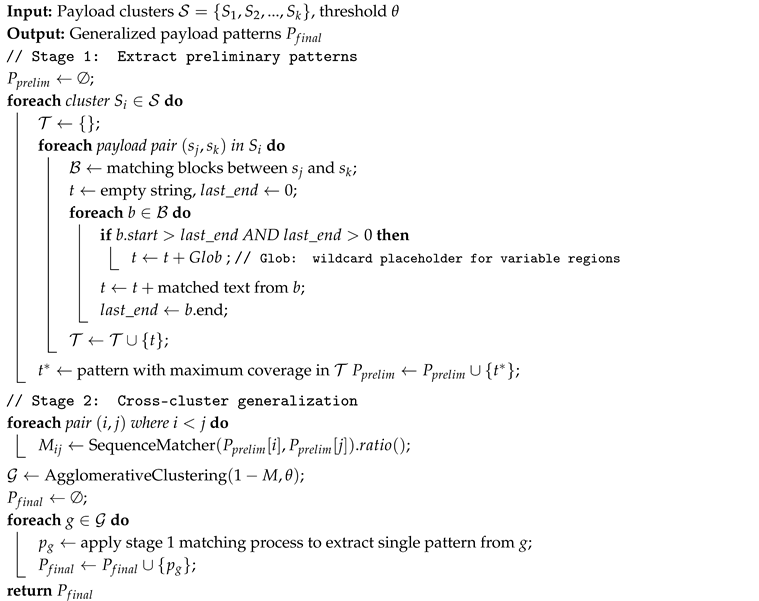

Payloads serve as the carriers of cyber bot behaviors, and the way in which cyber bots construct these payloads fundamentally drives their operational logic. To better understand the underlying generation principles, we examine the structure and content of payloads and categorize them into three types based on their degree of customization: fully customized payloads (11% of patterns), semi-customized payloads (82% of patterns), and default payloads (7% of patterns). The degree of customization reveals different approaches to payload construction, allowing us to understand the principles underlying cyber bot behavior generation.

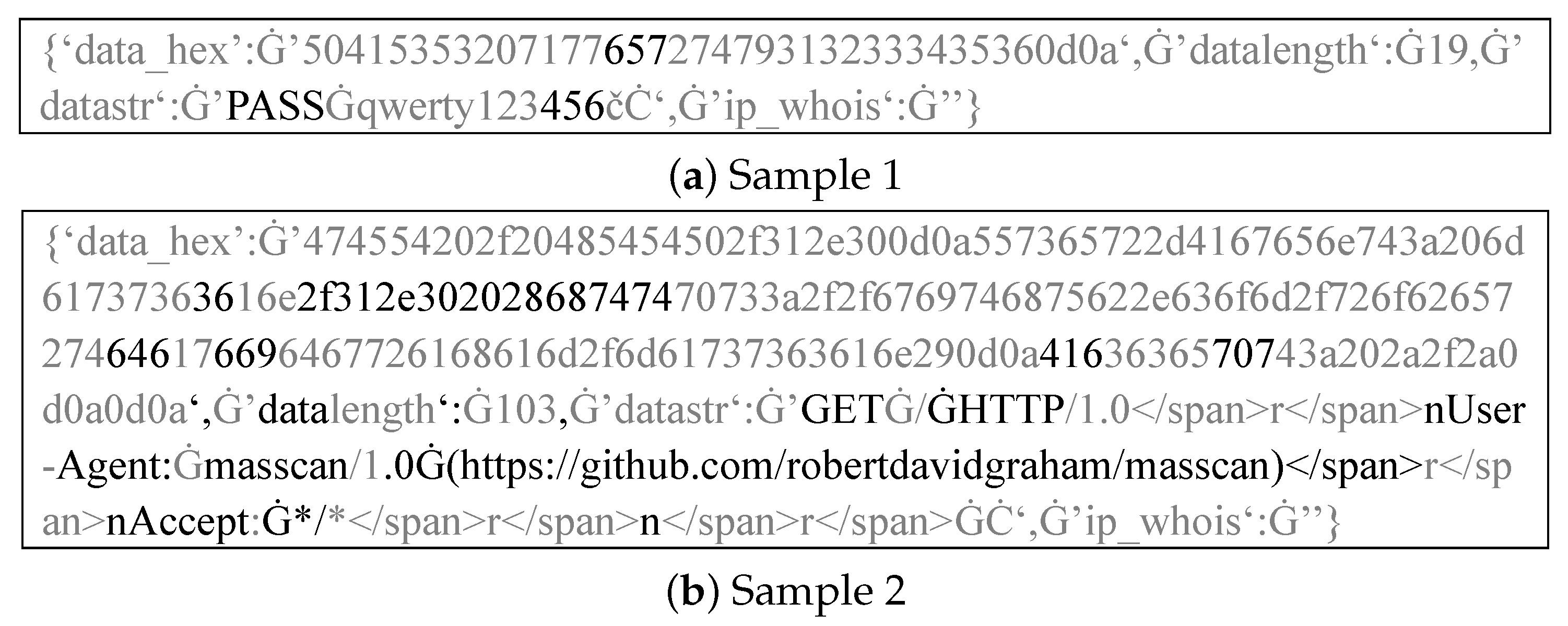

Fully customized payloads. These payloads, with the highest level of customization, are not based on any publicly recognized protocols and are specifically crafted for cyber bot activities. Through our payload pattern analysis, we observe that these payloads are frequently employed in generic probing activities rather than being tailored to interact with specific services or ports. The following are two representative examples of fully customized payloads:

MGLNDD_<IP><PORT>: A payload associated with the Magellan (MGLN) project [

58] from RIPE Atlas [

59], used for global connectivity measurement and reachability probing [

60].

LIOR*UP*ZZZZZZZZZ…ZZ: A non-standard payload with human-like filler text, appearing across various ports, likely used in automated probing to test service vulnerabilities or identify exposed resources [

61].

Semi-customized payloads. These payloads are crafted within the constraints of specific service protocols, often utilizing a predefined set of patterns. By combining standard elements with custom modifications based on the adversary’s objectives, these payloads introduce a significant degree of unpredictability in bot behaviors. Their ability to blend within normal protocol structures while incorporating variable, customized content makes them more difficult to detect and analyze.

In HTTP service-related traffic, we observe that many

HOST field contents include external links (see

Table 5). Through analyzing these

HOST fields, converting IP addresses to domain names via WHOIS lookups when necessary, we identify 5615 distinct domain names, with 1564 (27.9%) ranked among the top 1M domains according to Tranco [

62]. This suggests that adversaries select domains from popular libraries to ensure non-empty URLs [

63] or probe servers of popular websites to uncover hidden services or match server fingerprints. Less popular domains can serve as indicators of the organizations controlling cyber bots, since only specific entities are likely to access these obscure destinations. Additionally, in some HTTP-related CONNECT payload patterns, we find Base64-encoded identifiers that embed the request’s current timestamp. This suggests that these requests are likely generated by cyber bots that log or track scanning activity, possibly for replay or monitoring purposes [

20].

Default payloads. Beyond customized payloads, cyber bot activities frequently involve the use of default example payloads. These payloads, which are often based on publicly available templates or service-specific default configurations, allow cyber bots to interact with services in a standardized way. This behavior is typically observed when cyber bots engage in routine checks or simple verifications of service availability. Rather than requiring custom payloads, bots use these predefined templates to test service responsiveness, ensuring the targeted service remains operational for further exploitation. As shown in

Table 6, various default payloads are employed by bots across different services to conduct such basic functionality checks.

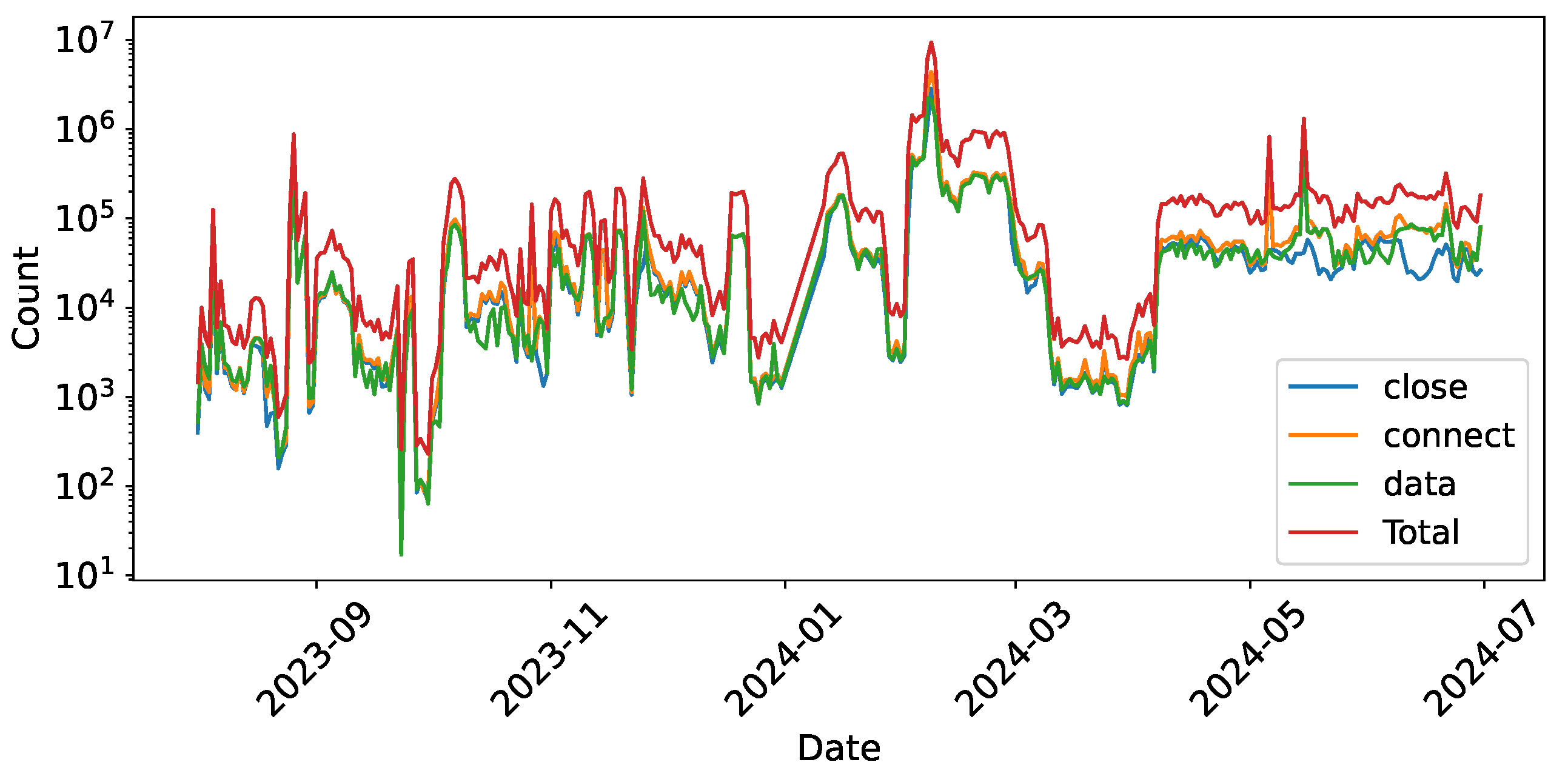

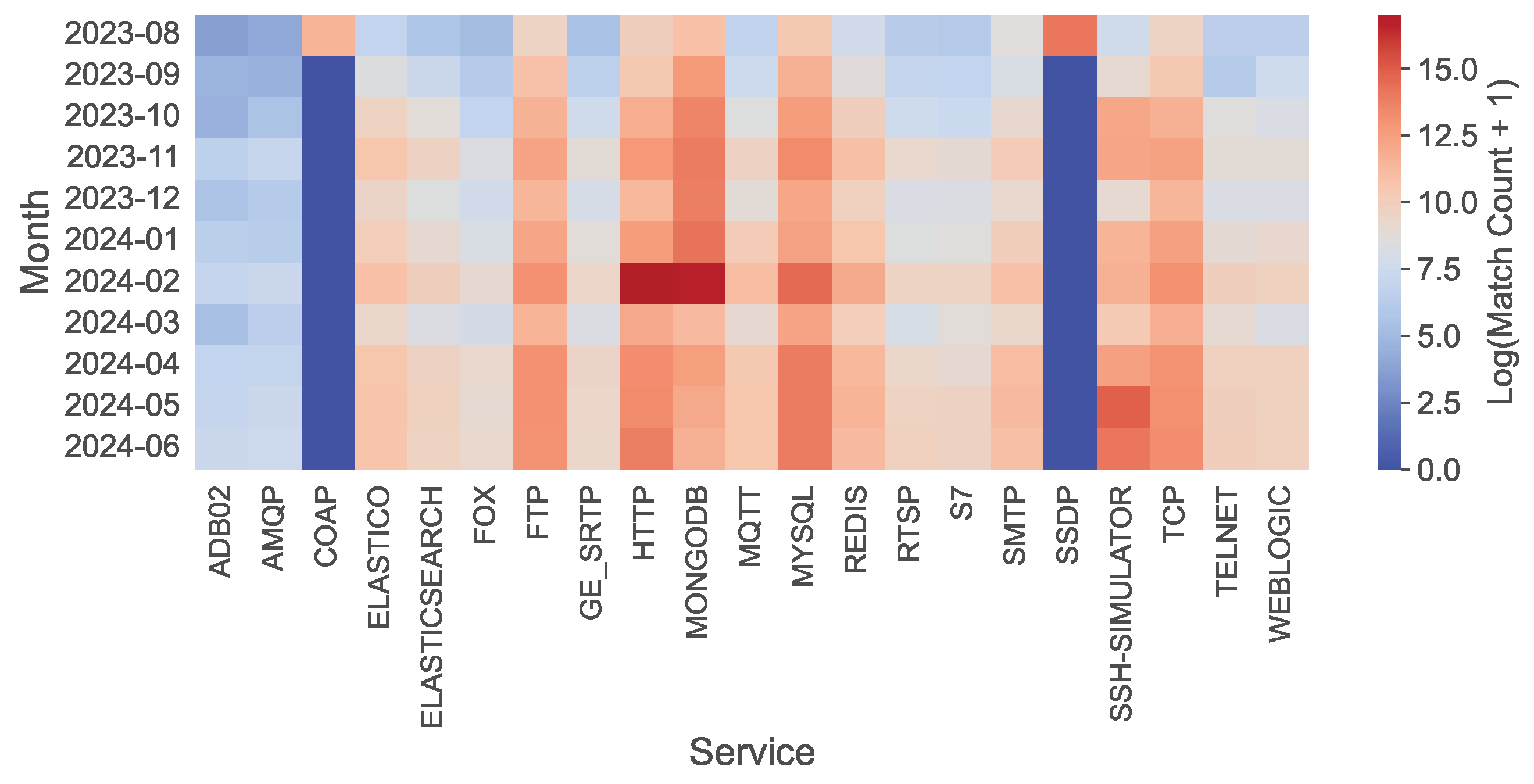

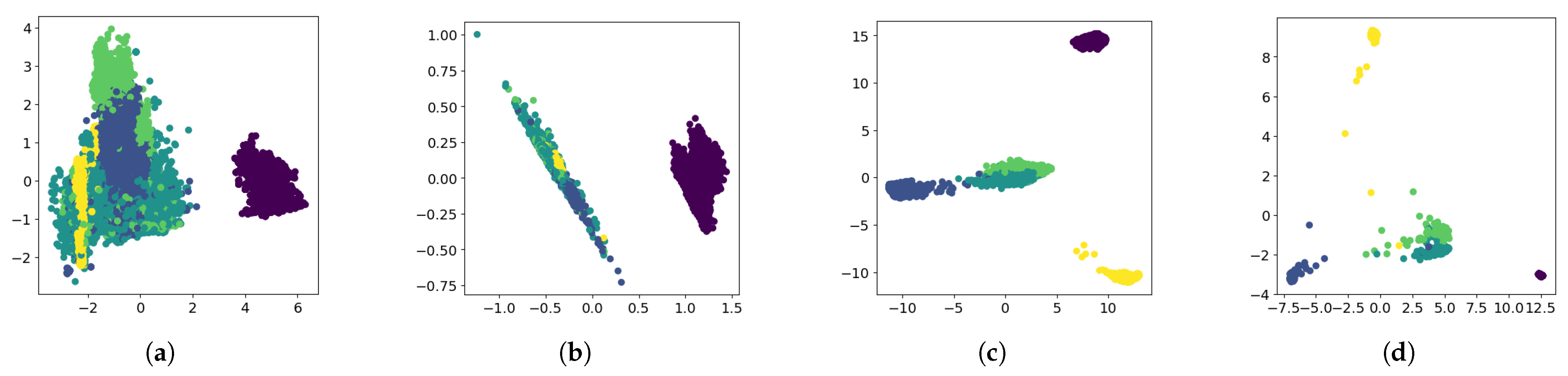

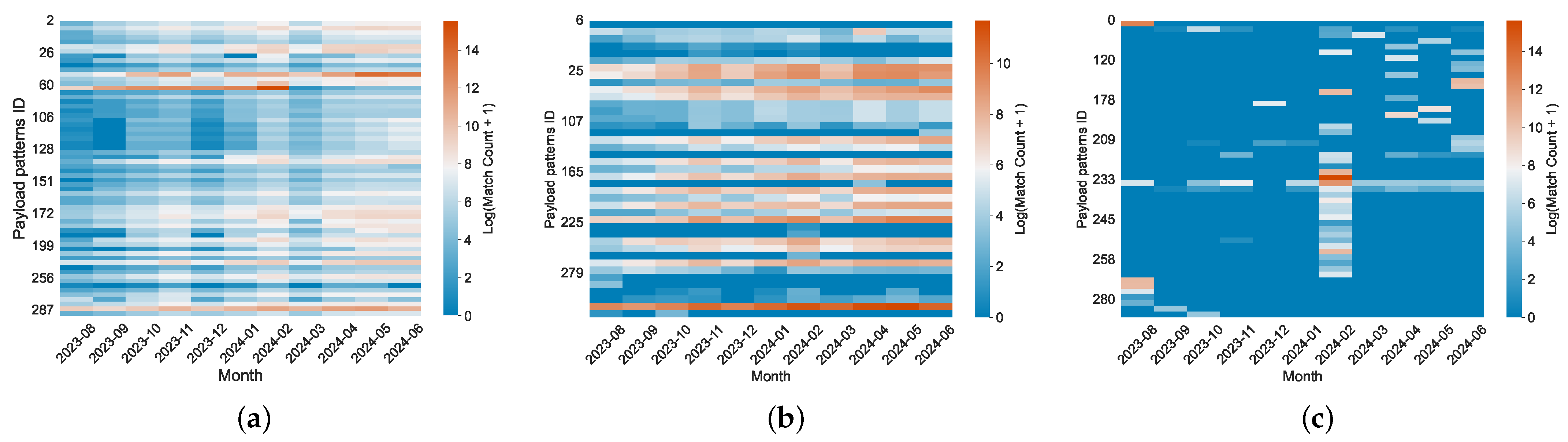

Temporal Modes. Although the generation principles of behaviors can be explained through payload structure, important information such as the timing and frequency of occurrences also plays a key role. We discover three time-dependent modes in 54% of the payload patterns, illustrated through separate heatmaps. As shown in

Figure 9a, we find that payload patterns (22%) show a matching trend consistent with the overall traffic volume for months, contributing to the traffic surge. Additionally, as shown in

Figure 9b, payload patterns (14%) demonstrate a weak temporal correlation (e.g.,

ZG\x00\x00\...x0e\x01\x00), likely indicating simple scanning activities conducted by a single organization within a specific cycle. Moreover, payload patterns (18%) exhibit a sharp increase in traffic during specific months (

Figure 9c). For instance, between February 4th and 22nd, the payload pattern

CONNECT *r:443 HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: www.guzel.net.tr:443\r\n Connection:keep-alive\r\nUser-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/117.0.0.0 Safari/537.36\r\n\r\n appeared in large volumes, originating from servers like tube-hosting.com. These requests predominantly involved hosts conducting CONNECT tests on HTTP services, targeting cloud service providers and proxy servers.

7.2. Identities (RQ2)

The identity behind cyber bot behavior can be inferred from the payloads. Among the 296 extracted payload patterns, 39 patterns (13%) reveal identity-related information. While not representing all payloads, these identity-revealing patterns provide valuable insights into the identities of cyber bots, including information about the organizations and tools. We analyze identity information based on the degree of disclosure, examining both explicit declarations and implicit revelations embedded in the payloads.

Explicitly. Cyber bots often assert their identity through the use of

User-Agent strings (See

Table 7) and client identifiers embedded in their payloads. This is particularly evident in protocols such as MQTT, SMTP, and RDP, where bots declare their presence via specific identifiers. For instance, in MQTT, a variety of identifiers associated with services like

CENSYS and

LZR [

67] are commonly observed. Similarly, in SMTP, cyber bots use the

EHLO command to introduce themselves and query service extensions. Our analysis shows frequent use of tools like

masscan and platforms such as

www.censys.io, indicating bots leverage these services to probe SMTP servers.

Table 8 presents the most common client identifiers observed. Additionally, some payloads feature empty or randomized identifiers, which do not declare a specific identity but are part of routine bot operations. On occasion, we observe payloads declaring themselves as legitimate Windows identifiers, such as

win-clj1b0gq6jp.domain. Further details regarding RDP-related client identifiers can be found in

Table 9. Notably, across all services, only 2 payload patterns from academic organizations included contact information and explicitly stated in the payload that users could make contact if they did not wish to be scanned. This provides users (i.e., scan targets) with an option to opt out.

Implicitly. In cases where cyber bots do not explicitly declare their identity, we infer it from pre-configured scripts, customized payloads (as discussed in

Section 7.1), and organizational usage patterns.

Cyber bots often rely on pre-configured scripts for their operations. When performing CRUD operations on databases, bots typically use specific object names, such as

yongger2 in

Table 10. Similarly, when connecting to external servers to download malicious code, these payload patterns include external links that reveal server IPs, domains, or file paths, as seen in

Table 10 (e.g.,

http://103.x.x.x/mps). These script behaviors serve as indicators of the cyber bot’s identity, as bots with similar configurations may share technical relationships. By recognizing these shared traits, defenders can shift from tracking individual IP addresses to defending groups of bots that exhibit similar behaviors.

Moreover, cyberspace search engines, such as Shodan, Censys, ZoomEye, and BinaryEdge, display distinctive cyber bot techniques. By analyzing the relative frequency of payload patterns within each platform, as summarized in

Table 11, we identify their distinct underlying strategies. Notably, Shodan, ZoomEye, and BinaryEdge all demonstrate some unexpected instances of brute-force attacks. Shodan particularly emphasizes encrypted communication protocols, exploring security policies like

STARTTLS and

AUTH TLS. In contrast, BinaryEdge relies heavily on Nmap, generating payloads derived from Nmap’s built-in features, including

GET /nice%20ports%2C/Tri%6Eity.txt%2ebak HTTP/1.0 and

sip:nm SIP/2.0\r\nVia:.... Interestingly, only Censys employs the payload pattern

*1\r$11\rNONEXISTENT\n, highlighting its distinctive approach to querying and identifying targets.

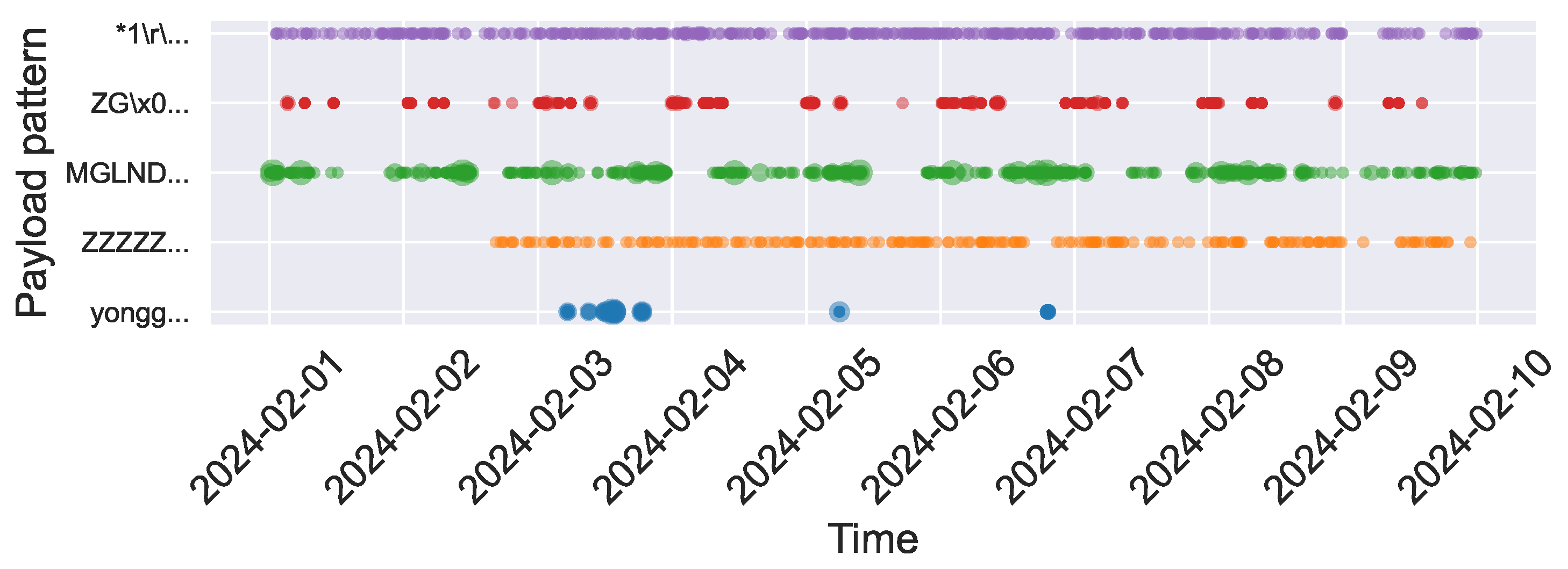

Based on the analysis above, we select payload patterns containing pre-configured file information, customized payloads, and those associated with specific organizations to examine periodic trends during the top 10 traffic days in February. As shown in

Figure 10, these payload patterns, which implicitly reveal cyber bot identities, exhibit clear periodicity and distinct behavioral patterns. These identity-specific behavioral signatures enable attribution beyond IP-based tracking: when similar payload sequences appear from new sources, defenders can cluster them as likely coordinated infrastructure based on shared configuration fingerprints [

9,

22], even when source addresses rotate. Within a 10-day observation window, the three pattern categories demonstrate distinguishable temporal characteristics. Organization-associated patterns like Censys (

NONEXISTENT, purple curve) maintain consistent daily reconnaissance activities. Customized payloads exhibit varied rhythms: some show intermittent activity within specific cycles (

ZG..., red curve), while others display persistent high-frequency scanning (

MGLNDD,

ZZZZZ, green and orange curves). Pre-configured scripts (

yongger, blue curve) demonstrate sporadic bursts characteristic of event-driven operations. These temporal patterns map to distinct cyber bot operational lifecycles, ranging from continuous reconnaissance to opportunistic exploitation phases. Such temporal behavioral signatures enable organization attribution [

38] and cyber bot type classification within short observation periods.

7.3. Strategies (RQ3)

We identify distinct cyber bot strategies by analyzing the extracted payload patterns. Through careful observation of both payload pattern content and associated traffic log metadata (such as protocol, port, IP, and timestamps) combined with domain expertise in cybersecurity, we classify these behaviors into five distinct categories. Our classification is derived from recognizable attack signatures, command structures, and interaction patterns observed across the dataset.

Table 1 defines and distinguishes the behaviors associated with these payload patterns. Among the labeled payloads, which are obtained using both public rules and TrafficPrint, the distribution across behavior categories is as follows: service scanning (78.14%), Web crawlers (0.39%), brute-force attacks (19.98%), vulnerability scanning (0.62%), and exploitation (0.86%).

Figure 11 visualizes the flow of cyber bot traffic, with the ports displayed on the left. The traffic corresponding to the payload patterns received by the honeypot’s forged services is then categorized according to specific cyber bot behaviors, where the width of the arrows indicates the contribution from each category. Analyzing different cyber bot behaviors provides insights into their strategic preferences, such as selecting specific services or adapting payload content to evade detection.

Service Scanning. The deployment of a multi-service honeypot significantly broadens the scope of cyber bot activities, leading to a wider variety of behaviors. Consequently, service scanning represents a substantial portion of the observed traffic.

Non-standard ports are commonly targeted in scans. The

mstshash parameter, associated with the Microsoft Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) cookie, frequently appears in payloads.

Table 9 lists the top 10 most common values for this parameter, which include valid usernames used by servers for client identification, load balancing, and session management [

68]. We observe a high volume of such payloads from cyber bots targeting the standard RDP port (3389). Notably, similar payloads are also found on a range of non-standard ports. This indicates that while developers recognize the prevalence of non-standard ports, adversaries are also adapting their scanning techniques to target these ports [

67].

Web Crawling. This behavior typically involves sending HTTP GET requests to retrieve web pages and parsing HTML content for links, text, and metadata. In our honeypot, we serve static interfaces rather than real website templates, limiting the effectiveness of metadata crawling. However, we observe generic reconnaissance behaviors, such as frequent requests for

robots.txt and

/sitemap.xml, which account for 35,961 out of 841,578 total HTTP requests (see

Table 12).

Malicious cyber bots often disguise themselves as legitimate web crawlers, like Googlebot or Bingbot, by spoofing the

User-Agent field (

Table 7). While search engine crawlers help users by indexing accessible links, they also provide attackers with a means to access sensitive resources undetected. For example, bots masquerading as

msnbot attempt to access sensitive files, such as

/systembc/password.php, indicating an attempt to exploit vulnerabilities. This underscores that in behavior detection, a bot’s observable actions are more reliable indicators than its declared identity, which may be spoofed.

Brute-force Attacks. Brute-force attacks systematically try all possible combinations to guess authentication credentials, relying on computational power, which leads cyber bots to employ targeted strategies to optimize the process.

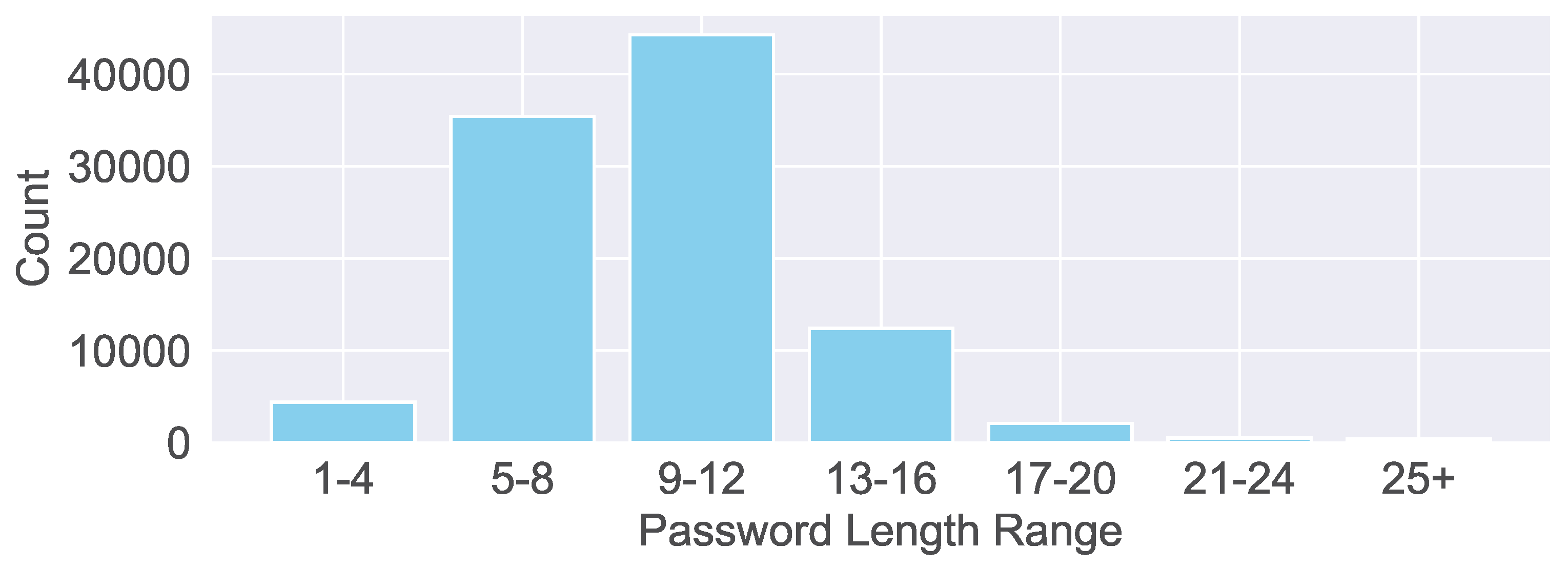

Weak passwords continue to be a primary focus within password dictionaries.

Figure 12 illustrates the distribution of password lengths used by cyber bots, with the majority falling between 9 and 12 characters. In contrast, credentials longer than 20 characters are generally considered more secure. In terms of password complexity, we observe the following distribution: low complexity (41.86%), consisting solely of letters; medium complexity (50.62%), incorporating both letters and numbers; and high complexity (7.53%), combining uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and special characters.

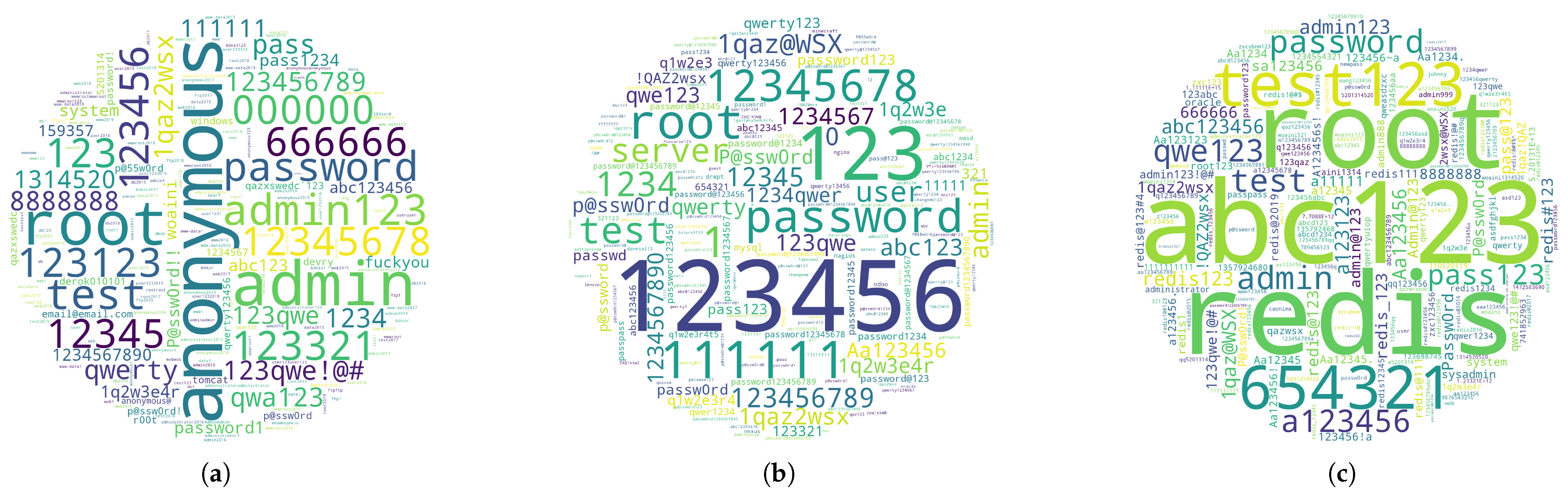

Cyber bots tailor their password sets to the specific service.

Figure 13 shows the passwords attempted on different services, demonstrating service-specific trends. For example, FTP servers often experience numerous login attempts with

anonymous as the password, while Redis servers see frequent use of

redis. The most common passwords for each service typically align with the legitimate default credentials. Adversaries regularly update and refine their dictionaries, making repeated attempts on compromised services.

Most cyber bots’ brute-force strategies remain unaffected by the password policy configurations of the targeted services. In classic versions of Redis, authentication relies solely on a password, without the need for usernames. Users only need to provide the password via the AUTH command upon connection. Our Redis instance intentionally omits a password setting, yet we still record a high volume of AUTH attempts. This indicates that cyber bots generally do not tailor their brute-force routines to the actual security configuration of a service, but instead follow a fixed authentication pattern regardless of whether password protection is enabled.

Different adversaries employ varied brute-force strategies. Some brute-force attempts include non-password commands, such as the INFO command in Redis or the QUIT command in FTP. This suggests that adversaries not only rely on password combinations but also issue system commands to gather additional information about the target system or terminate connections at specific points to evade detection. This hybrid strategy creates multidimensional attack vectors that challenge conventional defense mechanisms. Thus, analyzing the usage of these non-password commands can provide valuable insights into the attacker’s tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs), which can subsequently improve the specificity and effectiveness of defense measures.

Vulnerability Scanning. Vulnerability scanning builds on service scanning by querying for non-destructive defects once a service protocol is identified. As shown in

Table 13, cyber bots methodically target sensitive resources over HTTP services. Common targets include configuration files, such as

.env, which may expose credentials and system keys, and

.git/config files, revealing source code and version control histories. Misconfigurations in application servers, like Tomcat, can lead to unauthorized access, while paths like

/rediss.php?i=id and

/geoserver/web/ expose further attack vectors. Therefore, proper isolation of environments by function (development, testing, and production), encryption, access controls, and routine audits are essential to mitigate these risks.

Exploitation. Exploitation targets specific vulnerabilities, often requiring manual effort, but cyber bots can exploit common weaknesses with low-cost attacks, such as unauthorized access, interacting with external resources, or executing malicious commands like database deletion. From the number of log entries matching the payload patterns corresponding to exploitation behaviors, we obtain the most commonly used commands and scripts employed by cyber bots.

Table 10 lists these representative payloads.

Encoding-based evasion techniques, especially base64, are widely adopted by advanced cyber bots to conceal malicious intent and bypass basic defenses. Complex cyber bots often employ techniques aimed at bypassing basic signature-based defenses. We observe that adversaries convert executable files in Windows into hexadecimal format and insert them into SQL injection payloads, such as \x17\x1c\x00\x00\x03 set@a = concat(”,0x4D5A...0000). Additionally, they may encode malicious commands (e.g., curl, killall) or scripts from remote servers (e.g., //95.x.x.x:3306 /Tomcat Bypass/Command/Base64/Y3VybCAtcyA...) using base64 encoding, both to avoid encoding issues and to obscure their malicious intent. In the payload patterns that employed evasion techniques, 80% are encoded in base64.