Abstract

An emerging alternative to conventional piezoelectric technologies, which continue to dominate the ultrasound medical imaging (US) market, is Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducers (CMUTs). Ultrasound transducers based on this technology offer a wider frequency bandwidth, improved cost-effectiveness, miniaturized size and effective integration with electronics. These features have led to an increase in the commercialization of CMUTs in the last 10 years. We conducted a review to answer three main research questions: (1) What are the commercially available CMUT-based clinical sonographic devices in the medical imaging space? (2) What are the medical imaging applications of these devices? (3) What is the performance of the devices in these applications? We additionally reported on all the future work expressed by modern studies released in the past 2 years to predict the trend of development in future CMUT device developments and express gaps in current research. The search retrieved 19 commercially available sonographic CMUT products belonging to seven companies. Four of the products were clinically approved. Sonographic CMUT devices have established their niche in the medical US imaging market mainly through the Butterfly iQ and iQ+ for quick preliminary screening, emergency care in resource-limited settings, clinical training, teleguidance, and paramedical applications. There were no commercialized 3D CMUT probes.

1. Introduction

Ultrasound scanning (US) can image internal body structures non-invasively and in real-time [1]. This resulted in its universal spread in healthcare as an efficient screening tool for disease prevention and diagnosis and pregnancy monitoring [2,3]. Clinical US frequencies normally range between 2MHz and 18 MHz, where lower frequencies possess lower resolution yet deeper body penetration and vice versa [4]. Different types of US transducers are available, including linear, curvilinear, phased arrays, or minimally invasive endoscopic or intravascular arrays [5]. Each transducer configuration has different optimal applications [6]. For example, linear probes are typically used for superficial organs such as breast, thyroid, and musculoskeletal examinations, curvilinear probes are typically used for abdominal and pelvic scanning, and phased array probes are typically used for cardiac imaging [6]. An alternative to the conventionally employed US transducers based on piezoelectric crystals (PZTs) are MEMS-based piezoelectric (PMUT) or capacitive (CMUT) micromachined ultrasonic transducers [5]. CMUTs were first manufactured by Stanford University in 1994 and commercialized by Hitachi in 2008 [7,8,9]. A CMUT consists of a micro-thin, metallized membrane suspended above a conductive silicon substrate by insulating posts. The suspended membrane and silicon substrate act as electrodes. Driving alternating electric current across the biased electrodes vibrates the membrane due to the change in capacitance, generating high levels of US waves, and vice versa [10]. Compared to PZTs, CMUTs allow for a broader frequency bandwidth, are more cost-efficient, have a miniature size, and are more convenient for mass production. Moreover, they are suitable for more complex configurations and geometries, thereby potentially covering all the previously mentioned imaging configurations using a single transducer [4,8]. Due to their miniature size, CMUTs can also be used in minimally invasive treatments, including catheter-based and endoscopic applications, and are considered ideal for wearable US technologies [11,12,13]. In comparison with PMUTs, they possess a higher bandwidth and resolution, making them more suited for medical imaging, particularly for high-frequency applications [5]. These advantages led to their rapid commercialization by several companies [7,8,9,14,15]. Previous reviews have explored the technical capabilities and research potential of CMUTs in US medical imaging [8,14]. However, limited literature has been published on the current commercial and clinical performance and applications of CMUTs in the space. In 2019, ref. [14] reviewed the advances in CMUT technologies and estimated a total of 23 companies offering CMUT products. Yole Development conducted a market analysis on US in 2018 and 2020 [7,9]: in their analysis reports, they listed and categorized 24 organizations that are engaged in the commercialization of CMUT devices intended for various medical and non-medical applications. In this paper, we consider companies that have directly commercialized CMUT sonographic devices for medical imaging applications. All the CMUT-based products developed by these companies along with their application focus in the market and their performance are reviewed. We also report on all the future work expressed by studies released in the past 2 years to predict the trend of development in future CMUT device developments and express gaps in current research. This review aimed to answer three main research questions: (1) What are the commercially available CMUT-based clinical sonographic devices in the medical imaging space? (2) What are the medical imaging applications of these devices? (3) What is the performance of the devices in these applications?

2. Methods

2.1. Pre-Search

The methods of this review were detailed and registered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) under the same title. This review is the first of its kind, pioneering an exhaustive analysis of commercial products utilizing a specific technology. It systematically assesses their performance against conventional alternatives and clinical modalities. We devised a customized review approach which was revised by a university health faculty library liaison to retain the systematic nature of the review throughout. Utilizing the findings reported in [14] and the market analysis conducted by Yole Development [7,9], we identified 8 companies that have commercialized CMUT sonographic devices for medical imaging applications, using the eligibility criteria discussed in the next section: Butterfly Network (Guilford, CT, USA), Kolo Medical (San Jose, CA, USA), Verasonics (Kirkland, Washington, United States), Vermon (Tours, Centre, France), Hitachi (Chiyoda City, Tokyo, Japan), Siemens (80333 Munich, Germany), Acoustoelectronics Laboratory (ACULAB) (Unversità degli Studi Roma Tre, Rome, Italy), and Philips (Eindhoven, High Tech Campus 5, Netherlands). ACULAB was included as the only organization identified in the market analysis as actively involved in the industrialization and commercialization of CMUT devices. Websites of each company were also browsed for CMUT products to be included along with the company name in the searching stage.

2.2. Search Strategy

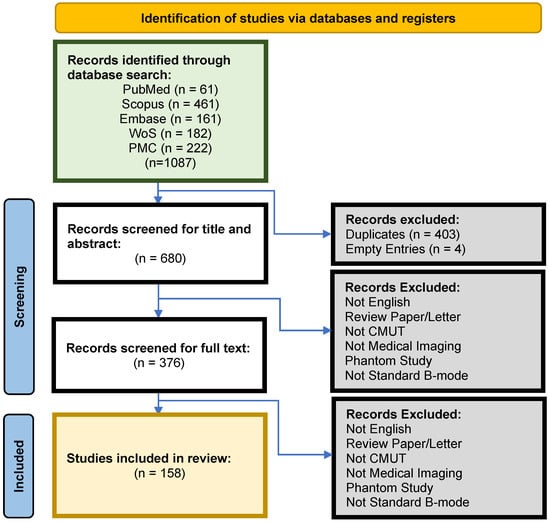

This systematic review was conducted in line with the PRISMA guidelines. Figure 1 illustrates the search protocol. The search strategy involved the 8 companies identified along with the products that are advertised on their websites. If the product was unnamed (e.g: CMUT Catheter for Therapy), it was not considered. Search strings were designed to capture the mention of the company in the context of CMUTs, the product in the context of the company, or the product in its own context. The main health databases were used: PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science. The company products were also searched on PubMed Central (PMC) to uncover studies that have not referenced the company or product used in the main fields. The timeline considered was until 18 June 2024 with no field restrictions on all databases. The search queries used for each database were detailed in the OSF-registered methods. Records retrieved were exported from each database as a .ris or .nbib file and imported into Mendeley. The total number of identified records was 1087. After excluding duplicates, there were 680 articles remaining. The identified records were then further inspected to assess their relevance based on the criteria outlined in the eligibility criteria section. Titles and abstracts were screened based on the eligibility criteria. The full text of each study was screened for eligibility, and the final number of included studies in the review was 158.

Figure 1.

PRISMA methods for systematic study selection.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review considered all the commercially available CMUT sonographic devices, probes, and catheters in the medical imaging domain. CMUT products used in studies were only deemed commercially available if they were developed by a specialized US company or organization. The scope of this review was limited to standard B-mode and Doppler-mode US modalities. CMUT products had to meet a minimum requirement of B-mode imaging capability, irrespective of their Doppler capabilities. Other US modes such as M- and A-mode were excluded. This review also only focused on standard US imaging, excluding other types such as photoacoustic and harmonic imaging, H-scan imaging, imaging with contrast agents, and high-intensity focused US. Included studies had to be either in vivo (human or veterinary) or cadaveric. This review was only concerned with clinical and pre-clinical CMUT performance, so phantom studies were excluded. In terms of article type, all studies were considered except for review articles and letters. Retracted articles were also excluded.

2.4. Data Extraction

Included studies were retrieved from Mendeley and imported into an Excel spreadsheet. For each paper, the title and citation, CMUT product utilized in the study, manufacturing company, application for which the product was employed, number of participants involved, and study design were extracted. Applications were based on the anatomy imaged and the objective of each study. The comparators, outcome measures, and corresponding performance results were recorded for evaluating the CMUT products. Additionally, information was extracted regarding the diagnosis and proposed procedure being investigated, as well as the anatomical organs and areas examined.

3. Results

3.1. Commercially Available CMUT Products

The search retrieved 19 commercially available CMUT products. No eligible Phillips products were found, so the company was excluded. There is a total of four clinically approved CMUT-based sonographic devices that are available in the market, produced by Butterfly Network and Hitachi. Hitachi was the first to introduce CMUT probes into the market with the Mappie system for breast cancer detection [16]. The product was later discontinued. In 2020, Hitachi commercialized the 4G SML44 CMUT probe. The company has experienced several mergers, splits, and acquisitions since its foundation in 1910. Most recently, their diagnostic imaging-related businesses were acquired by Fujifilm in 2021. Since, to the authors’ knowledge, no CMUT-based products were developed by Fujifilm since the acquisition, both Hitachi and Fujifilm were referred to in this review as one company using the original name, Hitachi. According to [16], the 4G CMUT probe is a single-probe solution that possesses an ultrawide-frequency bandwidth which is unachievable using conventional PZT probes and competes with high-end devices on high spatial resolution and sensitivity when imaging deep structures. Butterfly Network released a handheld CMUT probe called the Butterfly iQ (BiQ) in 2018 and then upgraded the probe to the Butterfly iQ+ (BiQ+) in 2020 [14]. Upgrades included shrinking the probe length and head, 60% higher frequency of pulse repetition, and 15% faster frame rates. The product was FDA-approved for 13 medical use cases and is composed of a 9000-element 2D CMUT array [14]. The device is a cost-effective single-probe solution, meaning that a single probe can emulate linear, curvilinear, and phased array configurations to image various body parts. The probe is coupled with a smartphone instead of a US system and features cloud-based services [14]. In February 2024, Butterfly Network launched its third-generation clinical US probe, the BiQ3, which won Best Medical Technology at the 2024 Prix Galien Awards (USA). With 2x the processing power of its predecessor, the BiQ+, the BiQ3 probe features enhanced image quality, frame rates, and frequency. Apart from ergonomic changes to probe design, size, and weight distribution to improve intercostal access in cardiac and pulmonary imaging and alleviate user strain, the BiQ3 introduces preliminary 3D imaging capabilities to HHUS through two novel presets: iQ Fan and iQ Slice. Over a region of interest, iQ Fan conducts continuous, real-time, bi-directional sweeps (±20°), whereas iQ Slice performs a single volumetric sweep, acquiring multiple slices of the region. However, both modes have their limitations, while the former preset is limited to pulmonary imaging, the latter mode is primarily for abdominal applications, with some pelvic and cardiovascular imaging. Despite extensive efforts detailed in the methods section, our review retrieved no studies on the BiQ3, likely due to its recent release. Kolo Medical has released six linear US probes (L62-38, L38-22, L30-14, M17-4, L22-8v, and L38-33v), two of which were commercialized in collaboration with Verasonics and based on the SiliconWave™ technology [8,17,18]. All their clinical CMUT sonographic devices are high/ultrahigh-frequency probes for high-resolution-related fields such as dermatology, ophthalmology, rheumatology, and musculoskeletal applications [18]. The rest of the companies, which include Vermon, Siemens, and ACULAB, have developed CMUT prototypes with specifications that are usually customizable based on the client’s research needs. ACULAB is also currently engaged in the development of volumetric imaging CMUT probes [19]. Specifications and details of all the commercially available CMUT products, at the clinical- and research-level, are presented in Table 1. Extracted raw results of review data can be found under Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

Details of all the commercially available products.

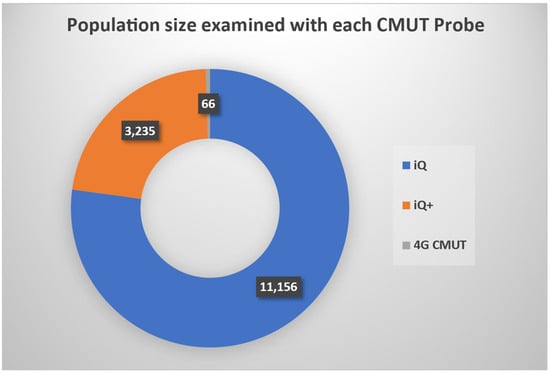

Notably, 99.5% of the total population size in the CMUT studies retrieved were imaged using the BiQ or BiQ+, as shown in Figure 2. Remaining probes imaged around a single patient each.

Figure 2.

Population size examined with each CMUT probe: BiQ, BiQ+, and 4G CMUT. Probes that are not visible in the chart did not report the scanned population size in their studies or had a relatively negligible sample size.

3.2. Applications and Performance

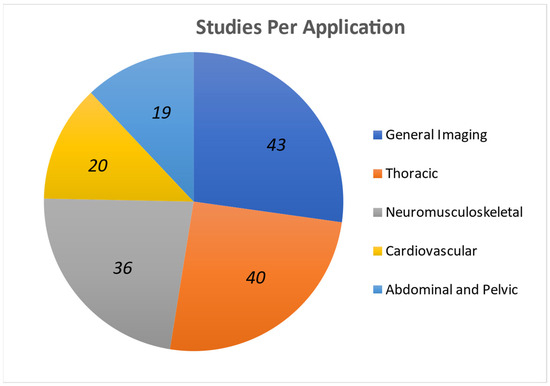

Medical applications in this review were categorized into thoracic, cardiovascular, abdominal and pelvic, neuromusculoskeletal, and general imaging US. Thoracic US involved the breast, chest, and/or neck region. Studies that did not focus on one of the above US applications were classified as general imaging.

In terms of performance, this review presents the key performance findings reported by the reviewed studies on commercial CMUT devices. Quantitative standardization and meta-analysis were outside the scope of this review. The performance of the devices was reported relative to one or more competitors whenever available in the studies. Comparators were either in the form of other medical imaging modalities, US devices, diagnostic techniques, or the same CMUT device in a different setting. The performance was reported in terms of metrics based on outcome measures specified by the reviewed studies. For each measure, quantitative performance data were prioritized, and when unavailable or impracticable to report in detail, a qualitative summary was provided. Reviewed studies sometimes reported results along with the statistical significance of findings (p-values (p)) and precision of the estimate (confidence intervals (CI)). p indicates the probability of observing a given result if no real effect exists, whereas the CI shows the range of plausible values for the estimated parameter. A p < 0.05 suggests that the observed result is statistically significant and unlikely to have occurred by chance. CI is generally selected at 95%, meaning that 95% of the population mean will fall between the upper and lower limits.

We classified the outcome measures into the following categories: Diagnostic Performance, Correlation, Image Quality, Learning Experience, and Satisfaction/Feasibility.

- Diagnostic Performance: a measure of the performance or accuracy of a diagnostic tool or method in detecting a condition. The performance metrics of this measure included the following:

- ∘

- Sensitivity (Se): the proportion of true positives among all patients with a condition/disease.

- ▪

- where TP = True Positives and FN = False Negatives;

- ∘

- Specificity (Sp): proportion of true negatives among all patients without a condition.

- ▪

- where TN = True Negatives and FP = False Positives;

- ∘

- Diagnostic Accuracy (DA): overall proportion of correctly identified cases, both true positives and true negatives. The general formula for DA is as follows:

- ▪

- ∘

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV): probability that a condition tested positive exists.

- ▪

- ∘

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV): probability that a condition tested negative does not exist.

- ▪

- ∘

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): area underneath the Receiver Operating Curve (ROC), which is a graphical representation of the true positive rate versus the false negative rate where their sum is equal to one, and they range from [0,1] and [0,1], respectively. AUC is ideally equal to 1 and at least larger than 0.5;

- ∘

- Diagnostic Duration (Time): time taken to complete a diagnostic procedure or obtain results;

- ∘

- Feasibility (Yes/No): determines whether a diagnostic method is practical and can be implemented effectively in clinical settings;

- ∘

- Cannulation or Injection Accuracy: rate or accuracy of successful cannulation or injection relying on a diagnostic tool/method for guidance;

- Correlation: a measure of the degree of similarity or agreement between test results and a reference standard, or the consistency between different observers and test conditions. Performance metrics included the following:

- ∘

- Inter-observer and Intra-observer Agreement (Kappa Agreement (k), ICC): this entailed two categories of agreement/reliability—agreement among different observers/operators/raters (interrater) over an identical exam and consistency of a single rater across repeated exams (intrarater);

- ▪

- Kappa Agreement/Cohen’s Kappa (k): agreement between two different raters on categorical assessments. It ranges from −1 (complete disagreement) to +1 (complete agreement), with 0 indicating random chance agreement. Standard k is usually employed for nominal categorical assessments, while variants are adapted for ordinal data or assessments by more than two raters;

- ▪

- Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC): reliability or consistency across two or more different raters on continuous measurements. This metric was also employed by studies for intrarater reliability. It typically ranges from 0 (no reliability) to 1 (perfect reliability);

- ∘

- Correlation with a reference standard (Pearson’s Correlation/Spearman’s Rank Correlation):

- ▪

- Pearson’s Correlation (r): measures linear relationship between two continuous assessment variables;

- ▪

- Spearman’s Rank Correlation: measures correlation of the rank of two variables. It indicates the degree to which the variables are monotonically related, even if their relationship is not linear;

- ∘

- Measurement Variability/Reproducibility: fluctuation of results of tests repeated under similar conditions.

The most common interpretation of correlation values is as follows:

- Values ≤ 0: no or poor agreement;

- Values 0.01–0.20: poor or slight agreement;

- Values 0.21–0.40: fair agreement;

- Values 0.41–0.60: moderate agreement;

- Values 0.61–0.80: substantial agreement;

- Values 0.81–1.00: almost perfect agreement;

- Image Quality: a measure of the clarity, resolution, and usefulness of images produced by diagnostic tools.

- ∘

- Image Resolution: spatial (e.g., axial and lateral) technical image details;

- ∘

- Image Clarity: delineation of structure, sharpness and presence of artefacts;

- ∘

- Interpretability: images deemed useful for diagnosis;

- Learning Experience: a measure of improvements in US training, knowledge, interpretation and technical skills related to diagnostic procedures, often before and after training or experience. Metrics included the following:

- ∘

- Skill Acquisition and Retention (Objective Structured Clinical Exams (OSCE), Exam Scores, Theoretical/Practical Tests): assesses how well trainees acquire and retain US skills over time, often through examination;

- ∘

- US and Anatomical Knowledge Improvement (Exam Scores): assesses, often through exams, the improvement in anatomical or US-specific knowledge after training;

- ∘

- Training Effectiveness (Experts vs. Novices): assesses the performance of a trainee post-training against experts;

- ∘

- Feasibility of Teleguided Learning: assesses the feasibility or performance of a trainee or a novice in conducting US examination and/or interpreting US findings with teleguidance;

- Satisfaction: a measure of user confidence, ease of use, and operational efficiency. Metrics included the following:

- ∘

- User Satisfaction Scores (Surveys, User Feedback): evaluates subjective satisfaction in using the US tool, often through surveys or user feedback;

- ∘

- Confidence in Self-Assessment (Confidence Percentage, Surveys): measures how well users feel they performed.

As shown in Figure 3, a significant proportion of the studies were dedicated to thoracic, general imaging, and neuromusculoskeletal applications. Studies were categorized as prospective (POS) or retrospective observational studies (ROS), cross-sectional studies (C-S), randomized control trials (RCT), case studies (CS), feasibility studies (FS), cadaveric studies (CAD), or veterinary studies (VET). Diagnostic Performance was the most employed outcome measure in terms of both number of studies and population size. Furthermore, as indicated in Table 2, the majority of the patients were studied prospectively, specifically 71.4%. Only 1.6% of the population size examined were cadaveric and veterinary.

Figure 3.

Applications and outcome measure statistics: number of studies that focused on each application.

Table 2.

Patient population size (n) per study design.

3.2.1. Thoracic

Whereas thoracic applications in this review involved the neck, breast, and lung regions, approximately 25% of studies were for pulmonary applications, making the lung the most examined structure. Table 3 details the performance of the CMUT products in thoracic applications. BiQ and BiQ+ were the only CMUT medical imaging devices used for pulmonary applications, where the former device was used in 88% of the studies, and it was a reference among Handheld US (HHUS) devices for lung US (LUS) and Emergency Room (ER) applications. Only four of the pulmonary studies were not COVID-19 related. Apart from availability, interest in the BiQ for COVID-19 applications is possibly due to the device’s ease of decontamination [30]. The device facilitated clinical assessments and decision-making for patients with COVID-19 of various severity presentations [31]. In many studies, it was able to identify, detect, and/or assess COVID-19-related pathologies and malaria cases [32], pulmonary oedema [32], post-acute sequelae (PASC) [33], and pneumonia and pneumothorax [31]. A retrospective study on 100 patients found that the BiQ could accurately assess moderate-to-high-severity COVID-19-related pathologies with 92% diagnostic accuracy [34]. Ref. [31] also retrospectively reported that LUS scores of 18 COVID-19 patients perfectly correlated (Pearson Correlation (PC) = 0.99) with a high-end US device, Venue Go. (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). Since chest CT is considered the gold standard for diagnosing lung pathologies [35], the BiQ was compared against chest CT and chest X-ray in nine studies. Ref. [36] compared chest CT with the BiQ in diagnosing 51 COVID-19 patients. The BiQ was 100% sensitive and 78.6% specific, highly correlating with chest CT with an ICC of 0.8. With chest X-ray, ref. [37] found a significant association (p = 0.034) between the decision-making for hospital referral using the BiQ and chest-ray based on a severity scale they constructed. The study concluded that the device could reduce uncertainty in moderate cases, facilitate prompt referral, and prevent unnecessary referral [37]. The BiQ also showed versatility in various thoracic settings, as it was found suitable for teaching LUS virtually and in person and for telemedicine with home-isolated COVID-19 patients [38,39,40,41]. It was easy to use and learn with adequate interobserver correlation for discerning abnormal LUS scans in 13 patients [42]; and when comparing 44 teleguided patients who were self-imaging their lungs against US experts’ results, there was an expert agreement of 87% and k = 0.49 [38]. Moreover, 98% of the patients felt confident in self-examination.

Table 3.

Performance of commercially available medical CMUT devices in thoracic US imaging applications.

3.2.2. Cardiovascular

The cardiovascular performance of the commercial CMUT probes is reported in Table 4. Around 13% of the CMUT studies were cardiovascular, less than 1% of which were neither BiQ nor BiQ+ related. Cardiovascular structures imaged using CMUTs in the literature included the heart [72], carotid artery [73,74], radial and ulnar arteries [75], internal jugular vein (IJV) [74,76,77], and inferior vena cava (IVC) [77]. The literature reports on the feasibility of the device for guiding cannulation in such structures [78]. The device significantly outperformed high-end US systems, such as the Mindray TE7 (Mindray North America, Mahwah, NJ, USA), for first-pass peripheral intravenous attempts (92.59% vs. 68.75%) when performed by emergency physicians on 59 patients with a history of difficult-to-obtain peripheral intravenous (PIV) access [79]. Two studies conducted on 113 patients in total showed that the BiQ is reliable for assessing the intravascular volume status to manage heart failure [74,76]. A US examination of the jugular venous pulsation using the device could accurately estimate right atrial pressure in both obese and non-obese patients, outperforming visual and IVC collapsibility assessments for obese patients [74,76]. Other studies reported on diagnosing venous gas emboli in divers’ arterial circulation, where results obtained by the BiQ demonstrated moderate agreement with Vivid q™ (GE Healthcare, Chicago) and O’Dive™ (Azoth Systems, Ollioules) [80]. The BiQ produced fewer quality images with inferior sensitivity and specificity than the former device, yet, higher than the latter device [80]. Overall, it was concluded that the device was not a replacement for post-dive venous gas emboli assessment [80]. Ref. [20] also used the BiQ to diagnose various cardiac presentations in the ER, including respiratory failure, dyspnea, novel atrial fibrillation, cardiogenic shock, and hypoxia. The device was adequate for cardiac imaging and could generally acquire all cardiac views, address basic resource-limited settings and clinical questions and identify substantial pathology [20]. The quality of the cardiac images was lower compared to the other presets in the probe itself (e.g., abdominal and musculoskeletal) due to a dip in resolution and frame rate, especially when Color Doppler was used [20]. The BiQ and most other HHUs lack advanced echocardiographic applications and spectral Doppler capabilities, rendering them less suitable for quantitative assessments [20]. In terms of US education, due to the absence of established cardiac POCUS training protocols in medical schools [81], the BiQ and BiQ+ were used as an educational or training tool for that purpose in four of the studies. Ref. [81] found that 54 medical students showed high satisfaction with the BiQ device. However, they struggled to learn US acquisitions through the PLAX, PSAX, and A4C views [81].

Table 4.

Performance of commercially available medical CMUT devices in cardiovascular US imaging applications.

3.2.3. Abdominal and Pelvic

Abdominal and pelvic studies (reported in Table 5) were 12% of the total number of papers retrieved. CMUT-based devices, and in particular the BiQ, have been used to image numerous abdominal organs, including the kidney, gallbladder [91], liver [24], spleen [6], and pelvis [92], as well as to examine the blood vessels that connect to some of these organs such as the aorta [93]. The BiQ was employed in large-scale hospital environments for abdominal imaging in four studies [20,91,93,94]. The overall performance of the BiQ in investigating causes of abdominal and obstetric presentations, ranging in degrees of severity, was found to be sufficient to resolve clinical questions. The device’s performance was also found to be outstanding in terms of image quality, particularly compared to its other modes such as cardiac imaging. The device outperformed clinical assessment for diagnosing and managing 19 patients presenting with kidney disease, confirming all findings and determining new ones in 30% of the cases in one instance [92] and determining 50% new findings in another study [95]. Sonographers referred to the images acquired by the CMUT device in the latter study as “stunning images” [95]. In terms of prostatic disease, the BiQ assessments correlated better against guideline imaging than other HHUS, such as the Clarius C3 (Virtual Way, Vancouver, Canada), in assessing the prostate gland volume of 78 patients in an RCT study (ICC 0.78 vs. 0.71), and it was found more reliable [96]. Studies also report on the feasibility of using the BiQ for monitoring pregnancy [94] and heart rate in newborns [97]. For vascular imaging in the abdomen, physicians from the Prince Sultan Military Medical City Hospital in Saudi Arabia compared the measurement reproducibility of the BiQ with a conventional US device (CUD), the EPIQ 7 (Philips, Bothell, WA, USA), on 114 participants for large-scale abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening [93]. Inter- and intra-operator reproducibility of aortic measurements correlated nearly perfectly (ICC > 0.8), except for the proximal location, with no struggle due to diminished spatial resolution or image acquisition [93]. The study concluded that the BiQ is an inexpensive, non-inferior alternative for AAA screening [93]. Similarly, a prospective protocol study was conducted using the BiQ+ on 1000 hospitalized patients presenting a picture of a common acute infection. The device was recommended to assess the presence of hydronephrosis as well as expedite the diagnosis [98]. Learning abdominal US using the BiQ also was not found challenging as 194 novices attained 96.4% diagnostically interpretable images for obstetric applications after only three hours of training [94]. A similar case was reported for the evaluation of the bladder (90% confidence level) and other pelvic structures (100% diagnostic accuracy) [99]. The reason for the ease of adoption and the outstanding performance of the BiQ in abdominal and pelvic applications is that while the depths of the abdominal organs are large and usually require a low-frequency curvilinear probe [100] (which is not the BiQ’s strength), the organs in this region are often large and may be easier to image compared to other regions.

Table 5.

Performance of commercially available medical CMUT devices in abdominal and pelvic US imaging applications.

3.2.4. Neuromusculoskeletal

Neuromusculoskeletal (NMSK) US can accurately expedite the identification of distinctive features of arthritic diseases and is considered to be nearing, if not on par with, MRI in imaging soft tissue injuries [111]. Approximately 23% of the CMUT studies found were NMSK-focused. For the overall performance of a commercial CMUT device in NMSK clinical applications other than the BiQ, three MSK radiologists retrospectively and independently compared the US exams acquired using the Hitachi 4G CMUT probe and a traditional L64 PZT probe (Hitachi Ltd., Chiyoda City, Tokyo, Japan) on an Arietta 850 workstation (Hitachi Ltd., Chiyoda City, Tokyo, Japan). The exams were for 66 patients with various MSK diseases [112]. Nearly one-third of the regions examined were shoulder-related [112]. The cases included the following: acute supraspinatus tendon tear, vastus lateralis muscle strain, entrapment neuropathy in the radial nerve, Dupuytren’s contracture, Ledderhose disease, Epicondylitis, and Acute De Quervain tenosynovitis [112]. There was a close correlation between the diagnostic performance of both probes [112]. Compared to the CUD, the 4G CMUT had better image panoramicity (width) and deep structure definition but poorer image quality in superficial tissue evaluations and the Doppler signal [112]. The authors concluded that improvements regarding these limitations must be made before the device could efficiently replace traditional PZT probes for this application [112]. As for the BiQ, physicians from an outpatient clinic compared the device with a CUD, HS40 (Samsung, Seoul, Seoul-t’ukpyolsi, Republic of Korea), by scanning 32 patients, at least one of whose joints were swollen and tender in order to assess the HHUS performance in inflammatory arthritis (IA) patients [113]. The study involved four different types of arthritis: rheumatoid, psoriatic, gouty, and lupus [113]. Images from both devices correlated nearly perfectly in B-mode (97%). The BiQ had a similar examination time to the CUD device, but it failed completely in detecting any Power Doppler (PD) signal in PD mode [113]. It was concluded that the B-mode BiQ was feasible and accurate for evaluating structural joint damage and inflammation in IA patients, but PD mode necessitates developments before it is viable for blood flow detection [113]. BiQ also had a similar performance to ophthalmic CUDs in ocular imaging [114,115]; it correlated well with arthroscopic findings [116], and it was even more sensitive than fluoroscopy [117,118] for ankle examinations on cadavers. However, it was less reliable than arthroscopy in distinguishing the different injury stages through sagittal translation in syndesmosis instability [116]. Moreover, BiQ proved to be viable for assessing and assisting in treating brain aneurysms (100% surgery success rate) in human and cadaveric brains [119]. In the arm, ref. [120] readily determined the nerve involvement and enlargement in eight patients with leprosy by imaging their wrist, forearm, elbow, and mid-humerus to visualize the bilateral median, ulnar, C5 root, and greater auricular nerves with a BiQ [120]. They compared it against a GE Logiq E (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), and despite the BiQ having one-third of the frequency bandwidth than that of the CUD, the cross-sectional areas measured with both devices correlated (Pearson product-moment correlation = 0.73 (p < 0.001)). They concluded that the device may assist in the diagnosis of leprosy in areas with limited healthcare resources because of the portability and low-cost nature of such devices [120]. An RCT conducted by [6] compared the BiQ with multiple CUDs on superficial structures of 29 patients and found no distinction in the diagnostic qualities of the images. Such diagnostic quality can be very useful in cases such as the ones discussed in [20] where, in a presentation of submandibular swelling of the jaw, the authors were able to identify a submandibular abscess using the BiQ. As for joints, ref. [121] proposed a protocol to scan hand, wrist, elbow, and shoulder joints using the BiQ for early detection of arthritis. They found that the course based on this protocol was fit for training dermatologists without pre-requisite knowledge [121]. Finally, numerous studies showed that the BiQ is very effective and easily taught by experts and student tutors alike [122] for NMSK US teleguided learning and even self-scanning [121,123]. Further performance details are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Performance of commercially available medical CMUT devices in neuromusculoskeletal US imaging applications.

3.2.5. General Imaging

Studies focusing on two or more of the specified US applications were categorized as general imaging. General imaging involves two very commonly employed exams: Rapid US for Shock and Hypotension (RUSH) and Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST). Both comprise examining structures in the lungs, heart, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis [146]. Ref. [147] compared the BiQ with the conventionally used US system, Phillips Sparq (Phillips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), in the ER on 50 healthy adults by conducting RUSH exams and found that the images did not differ in image acquisition latencies or image quality, concluding that the device may be an alternative for RUSH exams. Emergency physicians in another study also performed FAST exams on 29 patients in an RCT, comparing the BiQ against a GE LOGIQ S7 (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) with three different transducers: SP-D (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), C1-5-D (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), and ML5-15 (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), by scanning several body regions while switching between imaging pre-sets and transducers accordingly [6]. The process is also known as US hypotension protocols (UHPs) [6]. The time taken by the BiQ to perform the UHPs was significantly shorter than the CUD, by approximately 2 whole minutes (4.08 min vs. 5.8 min), and the number of diagnostic quality images did not differ between the two devices [6]. Ref. [148] also compared the image resolution, detail, and quality of the BiQ against the Sonosite M-turbo in an RCT on 74 patients using three blinded sonographers. Imaging purposes included the spine, transversus abdominis plane (TAP), and diagnostic obstetrics [148]. The BiQ was found to be superior in all image categories with the spine and similar in resolution and image quality in TAP images yet inferior in all image categories in obstetrical images [148]. The study concluded that the BiQ may be a POCUS alternative to the expensive machine; however, it is better suited for aesthetic rather than diagnostic obstetrical indications. To compare how the BiQ fares against a HHUS, 24 US experts compared the BiQ against three other HHUS, including the Vscan Air™ (GE Healthcare), the Lumify™ (Philips Healthcare) and the Kosmos™ (EchoNous, Inc.) systems, by examining patients through three POCUS views (FAST right upper quadrant view, transverse view of the neck with the IJV and carotid artery, and cardiac parasternal long-axis view) [149]. While BiQ ranked the second highest in ease of use, it was the worst by a large margin in terms of image quality and was indicated as the least likely to be purchased by the experts [149]. Two out of the three POCUS examinations were conducted with a cardiac preset, one of which relied on Color Doppler. Similarly, ref. [150] preferred the BiQ over Lumify™ (Philips Healthcare) in their educational prospective study for imaging deep and superficial structures but not for imaging the heart, lung, and abdomen. These studies may imply that the BiQ performs the poorest in cardiovascular imaging applications, particularly the ones involving Doppler capabilities, likely due to a poor phased array arrangement and its blood-flow monitoring for its weak Color Doppler features [100]. Details of the performance of the CMUT probes in general imaging applications are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Performance of commercially available medical CMUT devices in general imaging US applications.

3.3. Future Work of Modern Studies

Table 8 summarizes the future work reported by commercially available CMUT-related modern studies for the years 2023 and 2024. The trend focuses on expanding the range of clinical applications for CMUT-based HHUS, in particular BiQ and BiQ+, by validating the devices on larger patient populations in various settings, especially low-resource settings. The trend promotes improving training protocols to teach more medical practitioners, as well as non-practitioners, how to use the devices. Moreover, it promotes exploring the integration of AI to improve the devices’ utility. Only [142] has proposed interest in enhancing 3D imaging capabilities of CMUT-based HHUS devices.

Table 8.

Future work of commercially available CMUT-related modern studies for the years of 2023 and 2024.

4. Discussion

The review retrieved 158 studies and 19 standard medical imaging CMUT products, produced by seven US companies. Four clinically approved CMUT probes are currently available: the BiQ, BiQ+, BiQ3, and 4G CMUT probe. Hitachi and Butterfly Network shared a common interest in the single-probe CMUT capability, which was a characteristic exhibited by all three products. Hitachi was more engaged in developing a high-end CMUT device, while Butterfly Network focused on handheld US technologies. All other companies developed CMUT products for research purposes, primarily by having main CMUT products which they often adjust to manufacture tailored versions upon client request. Kolo Medical and Verasonics expressed interest in the high-frequency benefits of CMUTs, as evidenced by their exclusive production of high-frequency and ultrahigh frequency CMUT probes [18,182]. ACULAB’s exclusive area of focus centered on the utilization of reverse fabricated and dual probes, whereas Siemens prioritized exploring the potential of 3D imaging for CMUTs through the implementation of 2D arrays. Vermon was the only company manufacturing CMUT catheters.

With regards to applications and performance, ref. [14] postulated that CMUTs can replace PZT technologies in any medical US probe. This postulation is supported by retrieved results of this review, especially in instances where research-purposed CMUT probes were compared against their PZT counterparts and showed promising results [22,24,27,29,125]. Commercial products employing the CMUT technology have been used to image nearly every part of the body and for numerous applications and sub-applications, including pulmonary, cardiac, thoracic, endoscopic, vascular, ocular, cranial, musculoskeletal, nerve, and general imaging US. The devices have established their niche in the medical US imaging market mainly through the BiQ for quick preliminary screening, emergency care in resource-limited settings, clinical training, teleguidance, and paramedical applications, as reported by [20]. Ref. [20]’s study was the most pertinent to this review because it comprehensively evaluated the BiQ’s performance across diverse clinical applications and intercompared its presets, showing that the BiQ performed best in musculoskeletal and abdominal applications and was adequate, yet typically with relatively worse performance, for cardiac and blood-flow imaging (and in some applications not viable at all). The BiQ was an effective tool that offered good image quality in the majority of functions, especially when employed by experts [20], but it does not replace high-end US examinations as reported by [183].

In terms of limitations and future work, the literature has investigated the performance of the CMUT devices on approximately 14,462 human patients, which is considered a limited population size. Moreover, 92% of the studies were related to the BiQ and BiQ+, which are both handheld devices manufactured using the same technology. Generalizing the reviewed performance to CMUTs becomes challenging. A total of 25% of the studies were concerned with these products being used as training tools for medical students, suggesting that they may become the primary choice for education and general research US due to their teleguidance capabilities during self-isolation and being easy to learn [184]. No studies compared the relative performance of the BiQ, BiQ+, and BiQ3. In fact, no studies were retrieved on the performance of the BiQ3, possibly due to its very recent release. The only other clinical CMUT product, the 4G CMUT probe, was used to examine 66 patients in one application, which is not a sufficient sample size to generalize the performance of high-end CMUTs. Future studies shall examine a larger sample size and challenge the device in more applications and conditions. The high-frequency bandwidth advantage possessed by CMUTs suggests that they may excel in high-frequency applications, yet no clinical CMUT catheters were presently available. Their imminent development is anticipated through Vermon. There were also no commercialized dedicated 3D CMUT probes. Siemens and, according to [19], ACULAB are working towards them [26]. Future studies may also expand on the 3 BiQ3’s application-limited 3D imaging capabilities to design novel 3D US single-probe handheld devices. Despite the market focus of CMUTs being on wearable and handheld applications [5,11,185] and the technology’s ability to adopt complex array arrangements, configurations, and geometries, no commercially available wearable CMUTs existed to date, nor have any companies expressed interest in developing them. Furthermore, no studies have suggested such future work. We surmise that this advantage, along with portability, cost-efficiency, and frequency bandwidth, are the main reasons for CMUTs to replace PZTs. The medical imaging potential offered by CMUTs is substantial, and we expect the reviewed companies to continue discovering novel use cases and commercializing the technology at an even faster rate.

5. Conclusions

This review performed a systematic, exhaustive analysis of the currently available commercial CMUT systems in medical US imaging. Despite their recent introduction to the market in 2008, this review retrieved 19 devices, 4 of which were clinically approved. Available probes presented a promising alternative to the conventionally used PZT technology in the field, demonstrating comparable image quality and performance in many applications. The reviewed literature highlighted their distinct advantages, including wider frequency bandwidth, cost-effectiveness, miniaturized size, and integration capabilities with electronics. These qualities have encouraged their rapid commercialization, with emerging interest from US companies with large influence. Notably, the BiQ and BiQ+ have gained recognition for their suitability in quick preliminary screenings, emergency care in resource-limited settings, clinical training, and paramedical applications. The probes did not only establish themselves in diverse clinical applications but also in medical education and research. The teleguidance capabilities of these devices proved invaluable in self-isolation and remote learning settings. While the probes excelled in musculoskeletal and abdominal applications, their performance in cardiac and blood-flow imaging displayed some limitations. This review discovered limitations such as the relatively limited sample size of patients studied and the need for further research in various applications and conditions, especially for the 4G CMUT probe to investigate the technology’s performance in high-end US imaging. The potential for 3D US and wearable, distributed device imaging remains unexplored. Significant strides were made, and are being made, in commercial CMUT devices, and as these large companies continue to explore novel use cases of the technology, advancements in the field of US medical imaging are anticipated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/s25072245/s1, an Excel file including additional data extracted in the review has been attached to this submission.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., M.A. and D.F.; methodology, A.S., M.A., L.A., H.A.A. and J.R.; validation, A.S., M.A., L.A., H.A.A., J.R., P.P. and D.F.; formal analysis, A.S., L.A. and H.A.A.; investigation, A.S., L.A. and H.A.A.; resources, P.P. and D.F.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S., M.A., L.A., H.A.A., J.R., P.P. and D.F.; visualization, A.S., M.A., L.A., H.A.A. and J.R.; supervision, P.P. and D.F.; project administration, A.S., M.A., L.A. and D.F.; funding acquisition, P.P. and D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding support through the following funding schemes of the Australian Government: ARC Industrial Transformation Training Centre (ITTC) for Joint Biomechanics under grant IC190100020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors hereby declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carovac, A.; Smajlovic, F.; Junuzovic, D. Application of Ultrasound in Medicine. Acta Inform. Medica 2011, 19, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sceusa, D.K. 1065: Ultrasound of Abdominal Organ Transplantation. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2009, 35, S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethune, M.; Alibrahim, E.; Davies, B.; Yong, E. A pictorial guide for the second trimester ultrasound. Australas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2013, 16, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, V.S.P.; Burk, R.S.; Creehan, S.B.; Grap, M.J.P. Utility of High-Frequency Ultrasound: Moving Beyond the Surface to Detect Changes in Skin Integrity. Plast. Surg. Nurs. 2014, 34, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Schaijk, R. CMUT and PMUT: New Technology Platform for Medical Ultrasound. November 2018. Available online: https://www.engineeringsolutions.philips.com/app/uploads/2019/03/CMUT-and-PMUT-Rob-van-Schaijk-November-2018.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Sabbadini, L.; Germano, R.; Hopkins, E.; Haukoos, J.S.; Kendall, J.L. Ultrasound hypotension protocol time-motion study using the multifrequency single transducer versus a multiple transducer ultrasound device. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 22, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yole Developpement. Ultrasound Sensing Technologies for Medical, Industrial and Consumer Applications 2018 Report by Yole Developpement. 2018. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/ultrasound-sensing-technologies-for-medical-industrial-and-consumer-applications-2018-report-by-yole-developpement-107577886/107577886 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Saeidi, N.; Selvam, K.; Vogel, K.; Baum, M.; Wiemer, M. Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducers for Medical and Non-medical Applications; Fraunhofer ENAS: Chemnitz, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yole Developpement. From Technologies to Markets—Ultrasound Sensing Technologies 2020. 2020. Available online: https://medias.yolegroup.com/uploads/2020/11/YDR20134-Ultrasound-Sensing-Technologies-2020-Sample.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Roh, Y. Ultrasonic transducers for medical volumetric imaging. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 53, 07KA01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, A.; Choe, J.W.; Lee, B.C.; Cristman, P.; Oralkan, O.; Khuri-Yakub, B.T. Miniaturized, wearable, ultrasound probe for on-demand ultrasound screening. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, New York, NY, USA, 18–21 October 2011; pp. 1060–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.; Boulmé, A.; Sénégond, N.; Férin, G.; Legros, M.; Roman, B.; Teston, F.; Certon, D. Dual Mode Transducers Based on cMUTs Technology. In Proceedings of the Acoustics 2012 Nantes Conference, Nantes, France, 23–27 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, D.N.; Truong, U.T.; Nikoozadeh, A.; Oralkan, Ö.; Seo, C.H.; Cannata, J.; Dentinger, A.; Thomenius, K.; de la Rama, A.; Nguyen, T.; et al. First In Vivo Use of a Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasound Transducer Array–Based Imaging and Ablation Catheter. J. Ultrasound Med. 2012, 31, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, K.; Ergun, A.S.; Firouzi, K.; Rasmussen, M.F.; Stedman, Q.; Khuri-Yakub, B.P. Advances in Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducers. Micromachines 2019, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manwar, R.; Kratkiewicz, K.; Avanaki, K. Overview of ultrasound detection technologies for photoacoustic imaging. Micromachines 2020, 11, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitachi. Technology Innovation Finance, Public, Healthcare: Research & Development: Hitachi Review. 2018. Available online: https://www.hitachihyoron.com/rev/archive/2018/r2018_03/25/index.html (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Kolo Medical Inc. Products Series. Available online: http://www.kolomedical.com/xdwxl (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Verasonics, Inc. Verasonics®. CMUT Transducers—Verasonics. Available online: https://verasonics.com/cmut-hf-transducers/ (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Savoia, A.S.; Caliano, G. MEMS-Based Transducers (CMUT) and Integrated Electronics for Medical Ultrasound Imaging. In Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 431, pp. 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burleson, S.L.; Swanson, J.F.; Shufflebarger, E.F.; Wallace, D.W.; Heimann, M.A.; Crosby, J.C.; Pigott, D.C.; Gullett, J.P.; Thompson, M.A.; Greene, C.J. Evaluation of a novel handheld point-of-care ultrasound device in an African emergency department. Ultrasound J. 2020, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Zhao, D.; Chen, L.; Zhai, L. A 50-MHz CMUT Probe for Medical Ultrasound Imaging. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Kobe, Japan, 22–25 October 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhuang, S.; Daigle, R. A commercialized high frequency CMUT probe for medical ultrasound imaging. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, Taipei, Taiwan, 21–24 October 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermon. Innovations—Vermon MEMS. Available online: https://vermon-mems.com/innovations/#ressource (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Basset, O.; Bouakaz, A.; Sénégond, N.; Toulemonde, M.; Guillermin, R.; Fouan, D.; Lin, F.; Tourniaire, F.; Cristea, A.; Novell, A.; et al. Ultrasound imaging using CMUT—Techniques developed in the frame of the ANR BBMUT project. IRBM 2015, 36, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certon, D.; Legros, M.; Gross, D.; Vince, P.; Gens, F.; Gregoire, J.; Coutier, C.; Novell, A.; Bouakaz, A. Ultrasound pre-clinical platform for diagnosis and targeted therapy. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Chicago, IL, USA, 3–6 September 2014; pp. 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.; Daft, C.; Panda, S.; Ladabaum, I. 5G-1 Two Approaches to Electronically Scanned 3D Imaging Using cMUTs. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, Vancouver, Canada, 3–6 October 2006; pp. 685–688. [Google Scholar]

- Daft, C.; Wagner, P.; Bymaster, B.; Panda, S.; Patel, K.; Ladabaum, I. cMUTs and electronics for 2D and 3D imaging: Monolithic integration, in-handle chip sets and system implications. In Proceedings of the IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 18–21 September 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, A.; Caliano, G.; Pappalardo, M. A CMUT probe for medical ultrasonography: From microfabrication to system integration. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2012, 59, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, A.; Caliano, G.; Mauti, B.; Pappalardo, M. Performance optimization of a high frequency CMUT probe for medical imaging. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Orlando, FL, USA, 18–21 October 2011; pp. 600–603. [Google Scholar]

- Cid, X.; Wang, A.; Heiberg, J.; Canty, D.; Royse, C.; Li, X.; El-Ansary, D.; Yang, Y.; Haji, K.; Haji, D.; et al. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in the assessment of patients with COVID-19: A tutorial. Australas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 23, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, D.; De Vita, E.; Mezzasalma, F.; Lanzarone, N.; Cameli, P.; Bianchi, F.; Perillo, F.; Bargagli, E.; Mazzei, M.A.; Volterrani, L.; et al. Portable pocket-sized ultrasound scanner for the evaluation of lung involvement in coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2021, 47, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, C.M.; Adegbite, B.R.; Edoa, J.R.; Mombo-Ngoma, G.; Obone-Atome, F.A.; Heuvelings, C.C.; Bélard, S.; Kalkman, L.C.; Leopold, S.J.; Hänscheid, T.; et al. Point-of-care ultrasound to assess volume status and pulmonary oedema in malaria patients. Infection 2021, 50, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Weng, I.; Graglia, S.; Lew, T.; Gandhi, K.; Lalani, F.; Chia, D.; Duanmu, Y.; Jensen, T.; Lobo, V.; et al. Point-of-CareUltrasound Predicts Clinical Outcomes in Patients WithCOVID-19. J. Ultrasound Med. 2021, 41, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, T.; Edwards, L.; Rajasekaran, A.; Clare, S.; Lasserson, D. Point-of-care lung ultrasound in the assessment of suspected COVID-19: A retrospective service evaluation with a severity score. Acute Med. J. 2020, 19, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji-Hassan, M.; Lenghel, L.M.; Bolboacă, S.D. Hand-Held Ultrasound of the Lung: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung-Chen, Y.; de Gracia, M.M.; Díez-Tascón, A.; Alonso-González, R.; Agudo-Fernández, S.; Parra-Gordo, M.L.; Ossaba-Vélez, S.; Rodríguez-Fuertes, P.; Llamas-Fuentes, R. Correlation between Chest Computed Tomography and Lung Ultrasonography in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 2918–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Cebrián, A.; Alonso-Roca, R.; Rodriguez-Contreras, F.J.; Rodríguez-Pascual, M.d.L.N.; Calderín-Morales, M.d.P. Usefulness of Lung Ultrasound Examinations Performed by Primary Care Physicians in Patients with Suspected COVID-19. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 40, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiem, A.T.; Lim, G.W.; Tabibnia, A.P.; Takemoto, A.S.; Weingrow, D.M.; Shibata, J.E. Feasibility of patient-performed lung ultrasound self-exams (Patient-PLUS) as a potential approach to telemedicine in heart failure. ESC Hear. Fail. 2021, 8, 3997–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivetta, E.; Girard, E.; Locascio, F.; Lupia, E.; Martin, J.D.; Stone, M. Self-Performed Lung Ultrasound for Home Monitoring of a Patient Positive for Coronavirus Disease 2019. Chest 2020, 158, E93–E97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung-Chen, Y. Lung ultrasound in the monitoring of COVID-19 infection. Clin. Med. 2020, 20, e62–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokoohi, H.; Duggan, N.M.; Sánchez, G.G.-D.; Torres-Arrese, M.; Tung-Chen, Y. Lung ultrasound monitoring in patients with COVID-19 on home isolation. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2759.e5–2759.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Weng, Y.; Graglia, S.; Chung, S.; Duanmu, Y.; Lalani, F.; Gandhi, K.; Lobo, V.; Jensen, T.; Nahn, J.; et al. Interobserver Agreement of Lung Ultrasound Findings of COVID-19. J. Ultrasound Med. 2021, 40, 2369–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiphrakpam, P.D.; Weber, H.R.; McCain, A.; Matas, R.R.; Duarte, E.M.; Buesing, K.L. A novel large animal model of smoke inhalation-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leviter, J.; Auerbach, M.; Amick, M.; O’Marr, J.; Battipaglia, T.; Amendola, C.; Riera, A. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Curriculum for Endotracheal Tube Confirmation for Pediatric Critical Care Transport Team Through Remote Learning and Teleguidance. Air Med J. 2022, 41, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivetta, E.; Cara, I.; Paglietta, G.; Scategni, V.; Labarile, G.; Tizzani, M.; Porrino, G.; Locatelli, S.; Calzolari, G.; Morello, F.; et al. Diaphragmatic point-of-care ultrasound in COVID-19 patients in the emergency department—A proof-of-concept study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, B.; Schuit, F.; Lieveld, A.; Azijli, K.; Nanayakkara, P.W.; Bosch, F. Comparing lung ultrasound: Extensive versus short in COVID-19 (CLUES): A multicentre, observational study at the emergency department. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; A Zagzebski, J.; Hall, T.J.; Madsen, E.L.; Varghese, T.; A Kliewer, M.; Panda, S.; Lowery, C.; Barnes, S. Acoustic backscatter and effective scatterer size estimates using a 2D CMUT transducer. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008, 53, 4169–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bima, P.; Pivetta, E.; Baricocchi, D.; Giamello, J.D.; Risi, F.; Vesan, M.; Chiarlo, M.; De Stefano, G.; Ferreri, E.; Lauria, G.; et al. Lung Ultrasound Improves Outcome Prediction over Clinical Judgment in COVID-19 Patients Evaluated in the Emergency Department. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.B.; Hasara, S.; Coker, P. Identification of a branchial cleft anomaly via handheld point-of-care ultrasound. J. Ultrason. 2022, 22, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivetta, E.; Goffi, A.; Tizzani, M.; Locatelli, S.M.; Porrino, G.; Losano, I.; Leone, D.; Calzolari, G.; Vesan, M.; Steri, F.; et al. Lung Ultrasonography for the Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia in the Emergency Department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 77, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pafitanis, G.; Pawa, A.; Mohanna, P.-N.; Din, A.H. The Butterly iQ: An ultra-simplified color Doppler ultrasound for bedside pre-operative perforator mapping in DIEP flap breast reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2020, 73, 983–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, T.J.; Castaneda, B.; Iyer, R.; Baran, T.M.; Nemer, O.; Dozier, A.M.; Parker, K.J.; Zhao, Y.; Serratelli, W.; Matos, G.; et al. Breast Ultrasound Volume Sweep Imaging: A New Horizon in Expanding Imaging Access for Breast Cancer Detection. J. Ultrasound Med. 2022, 42, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagreiya, H.; Jacobs, M.; Akhbardeh, A. Novel Quantitative Tool for Assessing Pulmonary Disease Burden in COVID-19 Using Ultrasound. Med Phys. 2022, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, J.F.; Pokrzywa, C.J.; Brandolino, A.; Murphy, P.; A De Moya, M.; Carver, T.M.W. The Time Course of Recurrent Pneumothorax Development after Thoracostomy Tube Removal in Trauma Patients: An Ultra-Portable Ultrasound Study (UPUS Trial). J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2022, 235, S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, Z.E.; Ko, S.; Rogers, C.; Oropallo, A.; Augustine, A.; Pamula, A.; Berry, C.L. Prehospital portable ultrasound for safe and accurate prehospital needle thoracostomy: A pilot educational study. Ultrasound J. 2022, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, T.J.; Castaneda, B.; Parker, K.; Baran, T.M.; Romero, S.; Iyer, R.; Zhao, Y.T.; Hah, Z.; Park, M.H.; Brennan, G.; et al. No sonographer, no radiologist: Assessing accuracy of artificial intelligence on breast ultrasound volume sweep imaging scans. PLOS Digit. Health 2022, 1, e0000148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, R.; Chiem, A. 377 Peer-Instructed Teleguidance Ultrasound in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Randomized Control Equivalence Study. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2022, 80, S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.C.; Magee, M.; Goett, H.; Murrett, J.; Genninger, J.; Mendez, K.; Tripod, M.; Tyner, N.; Costantino, T.G. Lung Ultrasound vs. Chest X-Ray Study for the Radiographic Diagnosis of COVID-19 Pneumonia in a High-Prevalence Population. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 60, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilp, C.M.; Meijer, L.; Stocker, M.; Langermans, J.A.M.; Bakker, J.; Stammes, M.A. A Comparative Study of Chest CT With Lung Ultrasound After SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Assessment of Pulmonary Lesions in Rhesus Monkeys (Macaca Mulatta). Front. Veter- Sci. 2021, 8, 748635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, S.E.; Fatima, H.; Walsh, D.P.; Mahmood, F.; Chaudhary, O.; Matyal, R. Role of Ultrasound-Guided Evaluation of Dyspnea in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesthesia 2020, 34, 3197–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivetta, E.; Ravetti, A.; Paglietta, G.; Cara, I.; Buggè, F.; Scozzari, G.; Maule, M.M.; Morello, F.; Locatelli, S.; Lupia, E. Feasibility of Self-Performed Lung Ultrasound with Remote Teleguidance for Monitoring at Home COVID-19 Patients. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung-Chen, Y.; Hernández, A.G.; Vargas, A.M.; Doblado, L.D.; Merino, P.E.G.; Alijo, Á.V.; Jiménez, J.H.; Rojas, Á.G.; Prieto, S.G.; Abreu, E.V.G.; et al. Impact of lung ultrasound during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Distinction between viral and bacterial pneumonia. Reumatol. Clínica 2022, 18, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, N.M.; Jowkar, N.; Ma, I.W.Y.; Schulwolf, S.; Selame, L.A.; Fischetti, C.E.; Kapur, T.; Goldsmith, A.J. Novice-performed point-of-care ultrasound for home-based imaging. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaad, S.; Brahier, T.; Hartley, M.-A.; Cordonnier, J.-B.; Bosso, L.; Espejo, T.; Pantet, O.; Hugli, O.; Carron, P.-N.; Meuwly, J.-Y.; et al. Point-of-care lung ultrasonography for early identification of mild COVID-19: A prospective cohort of outpatients in a Swiss screening center. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung-Chen, Y.; Algora-Martín, A.; Llamas-Fuentes, R.; Rodríguez-Fuertes, P.; Virto, A.M.M.; Sanz-Rodríguez, E.; Alonso-Martínez, B.; Núñez, M.A.R. Point-of-care ultrasonography in the initial characterization of patients with COVID-19. Med. Clin. 2021, 156, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung-Chen, Y.; Rivera-Núñez, M.A.; Martínez-Virto, A.M. Lung ultrasound in the frontline diagnosis of COVID-19 infection. Med. Clin. 2020, 155, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golombeck, D.; Khandokar, R.; Fu, D.; Provenzale, A.; McGee, M.; Lin, M.; Rossi, D.; Maybaum, S. Acquisition of High-Quality Pulmonary Ultrasound Images in the Heart Failure Clinic Following a Short Period of Training. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, S211–S212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, J.; Taylor, H.; Goss, A.-M.; Tisovszky, N.; Sun, K.M.; O’toole, S.; Herriotts, K.; Inglis, E.; Johnson, C.; Penfold, S.; et al. Point-of-care ultrasound as a diagnostic tool in respiratory assessment in awake paediatric patients: A comparative study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2023, 109, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, S.; Garbe, J.; Böhm, S.; Eisenmann, S. Pneumothorax detection with thoracic ultrasound as the method of choice in interventional pulmonology—A retrospective single-center analysis and experience. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, N.; Sadri, Y.; Myslik, F.; Chenkin, J.; Cherniak, W. Self-administered at-home lung ultrasound with remote guidance in patients without clinical training. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulye, A.; Bhasin, A.; Borger, B.; Fant, C. Virtual immediate feedback with POCUS in Belize. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1268905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji-Hassan, M.; Călinici, T.; Drugan, T.; Bolboacă, S.D. Effectiveness of Ultrasound Cardiovascular Images in Teaching Anatomy: A Pilot Study of an Eight-Hour Training Exposure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S.; Miller, M.; Asha, S. Assessing the validity of two-dimensional carotid ultrasound to detect the presence and absence of a pulse. Resuscitation 2020, 157, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Harrison, J.; Dranow, E.; Khor, L. Point of Care Ultrasound of the Jugular Venous Pulse in the Upright Position (u2 Jvp) Predicts Elevated Right Atrial Pressure and Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure on Right Heart Catheterization in Obese and Non-obese Patients. Circulation 2020, 142, A16244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.; van Waart, H.; Vrijdag, X.C.E.; Mullins, D.; Mesley, P.; Mitchell, S.J. Arterial blood gas measurements during deep open-water breath-hold dives. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 130, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Harrison, J.; Dranow, E.; Khor, L. Abstract 16212: Ultrasound Jugular Venous Pulsation Outperforms Visual Assessment and Ivc Collapsibility for Central Venous Pressures in Obese Patients. Circulation 2020, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, L.L.C.; Wang, L.; Harrison, J.; Alijev, N.; Dranow, E. Ultrasound of the internal jugular vein (uJVP) with point of care ultrasound (pocus) correlates with elevated right atrial pressure (RAP) on right heart catheterization (RHC) in predicting 6-month mortality. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 2021, 77, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua Niyyar, V.; Buch, K.; Rawls, F.; Broxton, R. Effectiveness of Ultrasound-Guided Cannulation of AVF on Infiltration Rates: A Single-Center Quality Improvement Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021, 77, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, U.; Ray, K.; Dasgupta, S.; Jerusik, B. 124 Comparison of First-Pass Peripheral Intravenous Cannulation Using a Handheld Ultrasound Device to Using a Traditional High-End Ultrasound System: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2021, 78, S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimpour, K.; Brenner, R.J.; Dong, G.Z.; Cleve, J.; Martina, S.; Harris, C.; Graf, G.J.; Kistler, B.J.; Hoang, A.H.; Jackson, O.; et al. Comparison of Newer Hand-Held Ultrasound Devices for Post-Dive Venous gas Emboli Quantification to Standard Echocardiography. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 907651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jujo, S.; Lee-Jayaram, J.J.; Sakka, B.I.; Nakahira, A.; Kataoka, A.; Izumo, M.; Kusunose, K.; Athinartrattanapong, N.; Oikawa, S.; Berg, B.W. Pre-clinical medical student cardiac point-of-care ultrasound curriculum based on the American Society of Echocardiography recommendations: A pilot and feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jujo, S.; Sakka, B.I.; Lee-Jayaram, J.J.; Kataoka, A.; Izumo, M.; Kusunose, K.; Nakahira, A.; Oikawa, S.; Kataoka, Y.; Berg, B.W. Medical student medium-term skill retention following cardiac point-of-care ultrasound training based on the American Society of Echocardiography curriculum framework. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2022, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mchechesi, I.; Simemeza, T.M.; Chikuwadzo, B.; Keller, M. Zimbabwe telehealth pilot program identifies high risk patients in an underserved population using point of care echocardiograms and digital electrocardiograms. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 2021, 77, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladha, P.; Truong, E.; Kanuika, P.; Allan, A.; Kishawi, S.; Ho, V.P.; Claridge, J.A.; Brown, L.R. Diagnostic Adjunct Techniques in the Assessment of Hypovolemia: A Prospective Pilot Project. J. Surg. Res. 2023, 293, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, N.A.; Pedroja, B.S.; Li, H.F.; Sutcliffe, M. Brief training in ultrasound equips novice clinicians to accurately and reliably measure jugular venous pressure in obese patients. Australas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2023, 26, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stec, S.; Wileczek, A.; Reichert, A.; Śledź, J.; Kosior, J.; Jagielski, D.; Polewczyk, A.; Zając, M.; Kutarski, A.; Karbarz, D.; et al. Shared Decision Making and Cardioneuroablation Allow Discontinuation of Permanent Pacing in Patients with Vagally Mediated Bradycardia. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, L.; Vermeulen, J.; Wiegerinck, A.; Fekkes, S.; Reijnen, M.; Warlé, M.; De Korte, C.; Thijssen, D. Construct Validity and Reproducibility of Handheld Ultrasound Devices in Carotid Artery Diameter Measurement. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2022, 49, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, M.J.; Kropf, C.W.; Thomas, J.; Valentini, N.; Schmid, S.A.; Hunt, N. Pericardiocentesis During Transport for Cardiac Tamponade Complicating Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. Air Med J. 2024, 43, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, O.; Palmeri, M.L. TPU Based Deep Learning Image Enhancement for Real-Time Point-of-Care Ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2024, 10, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguero, P.; Barnes, R.F.; Flores, A.; von Drygalski, A. Teleguidance for Patient Self-Imaging of Hemophilic Joints Using Mobile Ultrasound Devices. J. Ultrasound Med. 2022, 42, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.; Desai, S.; Sikorski, M.; Fatupaito, G.; Tupua, S.; Thomsen, R.; Rambocus, S.; Nimarota-Brown, S.; Punimata, L.; Sialeipata, M.; et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasound by Nonexpert Operators Demonstrates High Sensitivity and Specificity in Detecting Gallstones: Data from the Samoa Typhoid Fever Control Program. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 106, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfuraih, A.M.; Alrashed, A.I.; Almazyad, S.O.; Alsaadi, M.J. Abdominal aorta measurements by a handheld ultrasound device compared with a conventional cart-based ultrasound machine. Ann. Saudi Med. 2021, 41, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlick, M.B.; Marini, T.; Drennan, K.; Dozier, A.; Castaneda, B.; Baran, T.; Toscano, M. Assessment of a Brief Standardized Obstetric Ultrasound Training Program for Individuals Without Prior Ultrasound Experience. Ultrasound Q. 2022, 39, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, S.; Carr, D.; Keeling, G.; Giza, G. Abstracts from the 40th Annual Dialysis Conference Held in Kansas City, Missouri, 8–11 February 2020. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2020, 40, 2S–18S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houze, A.; Baek, I.; Amerling, R. Point-of-service ultrasound (POSUS) in nephrology. Perit. Dial. Int. 2020, 40, 4S–5S. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, H.; Brar, H.; Henry, F.; Corrigan, D.; De, S. Can handheld point of care ultrasound probes reliably measure transabdominal prostate volume? A prospective randomized study. J. Urol. 2022, 207, 1362734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzar, S.; Bhat, R. Feasibility of handheld ultrasound to assess heart rate in newborn nursery. Resuscitation 2022, 179, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjøt-Arkil, H.; Heltborg, A.; Lorentzen, M.H.; Cartuliares, M.B.; Hertz, M.A.; Graumann, O.; Rosenvinge, F.S.; Petersen, E.R.B.; Østergaard, C.; Laursen, C.B.; et al. Improved diagnostics of infectious diseases in emergency departments: A protocol of a multifaceted multicentre diagnostic study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.; Fernandez, A.; Ramsukh, B.; Noel, O.; Prashad, C.; Bayne, D. Training and Implementation of Handheld Ultrasound Technology at Georgetown Public Hospital Corporation: A Low-cost Intervention to Improve Diagnostic Evaluation in a Resource-limited Urology Clinic. J. Endourol. 2022, 36, A1–A315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothberg, J.M.; Ralston, T.S.; Rothberg, A.G.; Martin, J.; Zahorian, J.S.; Alie, S.A.; Sanchez, N.J.; Chen, K.; Chen, C.; Thiele, K.; et al. Ultrasound-on-chip platform for medical imaging, analysis, and collective intelligence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asikhia, O.; Bhatnagar, N.; Au, A.; Lewiss, R.; Fields, M.; Chang, A.; Maloney, K.; Chu, T.; Bollinger, E.; Tam, A. 351 The Accuracy of Handheld Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Symptomatic Pregnant Patients in the Emergency Department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2022, 80, S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokaprakarn, T.; Prieto, J.C.; Price, J.T.; Kasaro, M.P.; Sindano, N.; Shah, H.R.; Peterson, M.; Akapelwa, M.M.; Kapilya, F.M.; Sebastião, Y.V.; et al. AI Estimation of Gestational Age from Blind Ultrasound Sweeps in Low-Resource Settings. NEJM Évid. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagavatula, S.; Thompson, D.; Dominas, C.; Haider, I.; Jonas, O. Self-Expanding Anchors for Stabilizing Percutaneously Implanted Microdevices in Biological Tissues. Micromachines 2021, 12, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittenhouse, K.J.; Vwalika, B.; Sebastião, Y.; Pokaprakarn, T.; Sindano, N.; Shah, H.; Stringer, E.M.; Kasaro, M.P.; Cole, S.R.; Stringer, J.S.A.; et al. Accuracy of portable ultrasound machines for obstetric biometry. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 63, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalfon, M.; Gardezi, M.; Heckscher, D.; Shaheen, D.; Maciejewski, K.R.; Li, F.; Rickey, L.; Foster, H.; Cavallo, J.A. Agreement and Reliability of Patient-measured Postvoid Residual Bladder Volumes. Urology 2023, 184, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, K.G.; Yoshida, A.; Juliato, C.R.T.; Sarian, L.O.; Derchain, S. Performance of a handheld point of care ultrasonography to assess IUD position compared to conventional transvaginal ultrasonography. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2024, 29, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachira, J.; Matheka, D.M.; Masheti, S.A.; Githemo, G.K.; Shah, S.; Haldeman, M.S.; Ramos, M.; Bergman, K. A training program for obstetrics point-of-care ultrasound to 514 rural healthcare providers in Kenya. BMC Med Educ. 2023, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duminuco, A.; Cupri, A.; Massimino, R.; Leotta, S.; Milone, G.A.; Garibaldi, B.; Giuffrida, G.; Garretto, O.; Milone, G. Handheld Ultrasound or Conventional Ultrasound Devices in Patients Undergoing HCT: A Validation Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, M.; Fernandez, A.; Ramsukh, B.; Noel, O.; Prashad, C.; Bayne, D. Training and implementation of handheld ultrasound technology at Georgetown Public Hospital Corporation in Guyana: A virtual learning cohort study. J. Educ. Evaluation Health Prof. 2023, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, D.; Züllich, T.F.; Schneider, C.; Yousefzada, M.; Beer, D.; Ludwig, M.; Weimer, A.; Künzel, J.; Kloeckner, R.; Weimer, J.M. Prospective Comparison of Handheld Ultrasound Devices from Different Manufacturers with Respect to B-Scan Quality and Clinical Significance for Various Abdominal Sonography Questions. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, D.; Bauer, A.H.; Patel, R.; Morgan, T.A. Problem Solved. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 40, 1693–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draghi, F.; Lomoro, P.; Bortolotto, C.; Mastrogirolamo, L.; Calliada, F. Comparison between a new ultrasound probe with a capacitive micromachined transducer (CMUT) and a traditional one in musculoskeletal pathology. Acta Radiol. 2020, 61, 1653–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte, G.; Bayat, S.; Tascilar, K.; Valor, L.; Schuster, L.; Knitza, J.; Schett, G.; Kleyer, A.; Simon, D. POS1394 accuracy and performance of a handheld ultrasound device to assess articular and periarticular pathologies in patients with inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 979–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]