Abstract

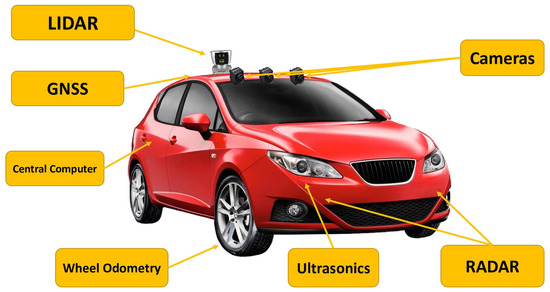

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) depend on perception, localization, and mapping to interpret their surroundings and navigate safely. This paper reviews existing methodologies and best practices in these domains, focusing on object detection, object tracking, localization techniques, and environmental mapping strategies. In the perception module, we analyze state-of-the-art object detection frameworks, such as You Only Look Once version 8 (YOLOv8), and object tracking algorithms like ByteTrack and BoT-SORT (Boosted SORT). We assess their real-time performance, robustness to occlusions, and suitability for complex urban environments. We examine different approaches for localization, including Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR)-based localization, camera-based localization, and sensor fusion techniques. These methods enhance positional accuracy, particularly in scenarios where Global Positioning System (GPS) signals are unreliable or unavailable. The mapping section explores Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) techniques and high-definition (HD) maps, discussing their role in creating detailed, real-time environmental representations that enable autonomous navigation. Additionally, we present insights from our testing, evaluating the effectiveness of different perception, localization, and mapping methods in real-world conditions. By summarizing key advancements, challenges, and practical considerations, this paper provides a reference for researchers and developers working on autonomous vehicle perception, localization, and mapping.

1. Introduction

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are poised to transform transportation by improving safety, efficiency, and accessibility. A crucial component of AV technology is the perception system, which enables vehicles to interpret their environment and make informed navigation decisions. However, real-world driving conditions pose numerous challenges, including occlusion, sensor limitations, and real-time processing constraints. Although previous surveys have reviewed perception, localization, and mapping methodologies, our study differentiates itself by not only analyzing existing research but also testing and evaluating various approaches for object detection, tracking, localization, and mapping in realistic scenarios.

This paper aims to comprehensively assess AVs’ perception, localization, and mapping techniques. We begin by analyzing the architecture and workflow of these modules, explaining how they interact to facilitate safe navigation. A detailed evaluation of existing datasets follows, focusing on their diversity, sensor configurations, and suitability for real-world applications. We then assess state-of-the-art object detection models such as You Only Look Once version 8 (YOLOv8) [1], Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) [2], Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN) [3], and tracking algorithms like DeepSORT [4], ByteTrack [5], Kalman filtering [6], and BoT-SORT (Boosted SORT) [7], examining their robustness under conditions such as occlusion, varying lighting, and dynamic traffic environments. Furthermore, we investigate LiDAR-based, vision-based, and sensor fusion-based localization strategies, discussing their accuracy and effectiveness in scenarios where Global Positioning System (GPS) signals are unreliable or unavailable. The mapping component of our study delves into Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) [8] and high-definition (HD) maps [9], evaluating their role in creating real-time, dynamic environmental representations for AV navigation.

Unlike many studies that rely solely on literature reviews, this paper integrates empirical insights from our experimental testing. We implemented object detection and tracking pipelines, evaluated different localization techniques, and tested mapping methods using high-resolution cameras, light detection and range (LiDAR) sensors, inertial measurement units (IMUs), and other sensor technologies. Our experiments assess the performance of these algorithms under real-world conditions, including adverse weather, occlusion, and urban traffic complexities. Synthesizing theoretical advances with practical testing offers a realistic perspective on what works best for AV perception and navigation.

This paper is structured into eight sections, each addressing a fundamental component of AV perception, localization, and mapping. Section 2 explores object detection and tracking, detailing the evolution of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in AV perception and comparing one-stage and two-stage detection models. We discuss how tracking algorithms such as DeepSORT [4], BoT-SORT [7], and ByteTrack [5] maintain object identity over time, particularly in challenging scenarios. Section 3 focuses on key object detection and tracking challenges, including occlusion, adverse weather conditions, and nighttime performance. Section 4 reviews commonly used datasets such as KITTI, nuScenes, and Waymo Open Dataset, evaluating their sensor configurations and annotation quality. Moving beyond perception, Section 5 examines localization techniques, comparing vision-based, LiDAR-based, and sensor fusion approaches and their effectiveness in achieving precise vehicle positioning. Section 6 explores different mapping technologies, discussing traditional digital maps, HD maps, and SLAM-based real-time mapping. As an alternative approach, Section 7 investigates the emerging concept of mapless navigation, which reduces dependency on prebuilt maps by leveraging SLAM, visual odometry, and deep learning techniques. Finally, Section 8 synthesizes our findings, discussing the remaining challenges in AV perception and mapping while outlining potential future research directions, such as improving real-time processing efficiency, optimizing sensor fusion strategies, and developing adaptive mapping techniques.

This paper integrates insights from the literature with experimental evaluations, serving as a practical reference for researchers, engineers, and industry professionals working on the perception, localization, and mapping of AV. Our goal is to bridge the gap between theoretical advancements and real-world implementations, ensuring that AV systems are robust in simulation environments and capable of functioning reliably in diverse and dynamic real-world scenarios.

2. Object Detection and Tracking in Autonomous Vehicles

2.1. Introduction to Image Processing in Autonomous Vehicles

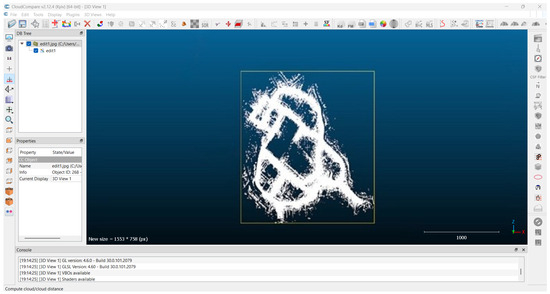

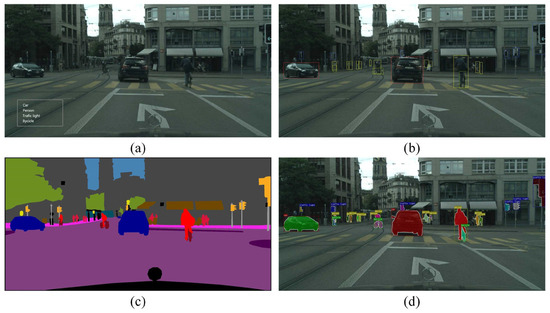

Autonomous vehicles rely heavily on image processing to understand and interact with their environment. The journey begins with image classification, where various features within an image are identified and categorized, such as classifying an object as a “car” or “pedestrian”. However, image classification alone is insufficient for AVs, as they need to know where objects are located in the scene. This leads to object detection, which involves identifying and localizing objects within an image, often represented by bounding boxes around the objects. Moving further into the image processing chain, the segmentation of the image provides a more detailed understanding by classifying each pixel in the image, which is crucial for accurate scene understanding in complex environments like roads with multiple moving objects, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Relationship between different vehicle detection algorithms: (a) object classification, (b) object detection, (c) semantic segmentation, (d) instance segmentation. Source: [10].

2.2. Overview of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [11] form the backbone of modern image processing and object detection in AVs. A CNN comprises multiple layers, each performing a specific function to process an input image and extract meaningful information. An array of input signals is transformed into an array of output signals in each convolutional layer. Each output is called a feature map. If the input is a picture, this feature map will be a 2D array of color channels; if the input is a video, this feature map will be a 3D array; and for audio input, it will be a 1D array.

- Input layer: Larger structures are introduced to a network by input layers, which are normally represented by an image consisting of a multi-dimensional array of pixels. When images are to be put in a model, they should conform to the region, channel dimensions, and the model or deep learning library.

- Convolution layer: while a kernel specifies the view size in the convolution operation, a filter, regarded as a tensor in this occasion, is the total number of kernels in a given layer channel-wise, for example, a filter with dimensions, has c pieces of kernels.

- Padding: Using this mechanism, the picture is resized in the spatial dimension, and the number of channels depends on both the input and the filter size. Parameters of the kernel define features that present edges in the output that are relevant to those characteristics.Padding adds a number of pixel grids to extend the spatial plane’s output dimensions. It also addresses the common problem of information loss. Thus, padding is a critical factor in convolutional neural network architecture and performance.

- Stride: stride relates to the translation distance in pixels when convolving the images.

- Activation functions: A feature of the network requiring more dense representation has its respective feature map built via the activation function, transforming the feature map into a nonlinear zone and allowing the model to learn complex tasks over data. The model can be made for more complicated structures by permuting the straight surfaces. For relief, the famous option for CNNs defeats the vanishing gradient problem.

- Pooling operation: The pooling layers in CNNs remove small rectangular structures from the output feature map, and each small block chooses a single maximum, minimum, or average number. With this adjustment, the feature map’s parameters and spatial size are smaller, making it easier to aim at microregulation. There are different sorts of pooling, such as maximum pooling or global average pooling. The second is when the whole image is pooled but nothing undergoes a sliding operation.

- Fully Connected Layers: after completing the convolutional and pooling processes, the last part of the CNN structure is the Fully Connected Layers (FCLs) used for high-level classification.

CNNs excel at handling complex tasks like object detection and tracking, enabling AVs to process real-time information with high accuracy.

2.3. Object Detection Networks

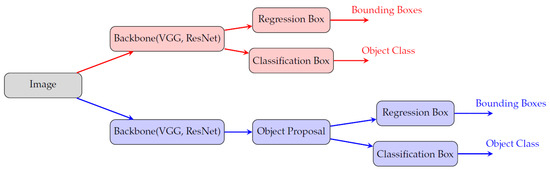

Object detection involves recognizing objects and pinpointing their locations within an image. Several CNN-based architectures have been developed to achieve efficient and accurate object detection in real time. These architectures are typically categorized into two-stage and one-stage detectors, as given in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Difference between one-stage and two-stage object detection. (Red color is for single stage detection and blue color is for two stage detection.

2.3.1. Two-Stage CNN Detectors

Two-stage CNN detectors have been integral to the evolution of object detection, beginning with R-CNN (Region-based Convolutional Neural Network), introduced in 2014 by Girchick et al. [12] This model relies on region proposals, which are processed individually through a backbone network, such as AlexNet. Despite achieving a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 58.5% on the Pascal VOC dataset, R-CNN suffered from slow processing speeds (one frame per second) and high computational demands, making it impractical for real-time applications.

In 2015, SPP-Net (Spatial Pyramid Pooling Network), proposed by He et al. [13], introduced spatial pyramid pooling to reduce redundant processing of region proposals, improving computational efficiency. SPP-Net achieved an improved mAP of 60.9% on the Pascal VOC dataset, but the multi-stage training process remained a drawback.

Later in 2015, Girshick [14] introduced Fast R-CNN, which brought significant improvements by incorporating a Region of Interest (RoI) pooling layer, leading to faster training and testing. This model achieved up to a 70.0% mAP on the Pascal VOC dataset, offering advantages like end-to-end training and improved accuracy compared to earlier models.

By 2016, Faster R-CNN, developed by Ren et al. [3], further improved on its predecessors by integrating a Region Proposal Network (RPN) to generate region proposals directly from the image, bypassing external proposal algorithms. Faster R-CNN provided faster and more accurate detection due to the unified proposal generation and classification process.

In the same year, R-FCN (Region-based Fully Convolutional Network), developed by Dai et al. [15], addressed translational invariance through position-sensitive score maps. R-FCN demonstrated strong performance, achieving an 80.5% mAP on the Pascal VOC dataset with the ResNet101 backbone.

Building on the success of Faster R-CNN, Mask R-CNN extended its capabilities to instance segmentation by adding a RoIAlign layer. Mask R-CNN further improved detection and segmentation accuracy, achieving excellent performance using the ResNeXt-101 backbone.

FPN (Feature Pyramid Network), proposed by Lin et al. [16] in 2017, enhanced object detection by fusing multi-scale features, improving the detection of objects at different scales. FPN delivered state-of-the-art results on the MS COCO [17] dataset, cementing its place in two-stage detectors.

Further innovations in 2018, such as NASNet, used learned features from image classification to improve object detection, achieving a 43.1% mAP on the MS COCO dataset with a Faster R-CNN framework.

In 2020, DETR (Detection Transformer), developed by Facebook AI [18], introduced a transformer-based encoder–decoder architecture for object detection. DETR achieved a 44.9% mAP on the COCO dataset, operating at 10 frames per second.

2.3.2. One-Stage CNN Detectors

One-stage CNN detectors aim to simplify the object detection pipeline by predicting object locations and classes in a single pass, without the need for region proposals. In 2016, SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector), proposed by Liu et al. [2], used multi-scale feature maps with a VGG-16 backbone to efficiently detect objects. SSD achieved a remarkable balance between speed and accuracy, operating at 59 fps with its SSD300 architecture.

SqueezeDet, inspired by YOLO and SqueezeNet [19], was designed for real-time embedded applications where power and energy consumption are critical. SqueezeDet achieved 57 fps, making it an ideal choice for real-time scenarios with limited resources, while still maintaining high accuracy.

In 2018, MobileNetV2-SSDLite was introduced by Howard et al. [20] as an improvement for real-time object detection on mobile devices. This model utilized the lightweight MobileNetV2 backbone, reducing the number of parameters and computational load while still providing efficient object detection performance.

In 2019, CenterNet [21], proposed by Zhou et al., advanced key-point-based object detection. By predicting a triplet of key points (center, top-left, and bottom-right) for each object, CenterNet improved accuracy and achieved a 47.0% mAP on the COCO dataset using the HourGlass-104 backbone.

The series of YOLO models achieves the real-time perception for advanced driver assistance systems where low latency and high accuracy are essential for safety-critical applications. In its latest version, YOLOv8, significant improvements guarantee better detection deployment for autonomous driving. With a better CSPDarknet-53 backbone, anchor-free detection, and adaptive feature fusion, YOLOv8 improves vehicle, pedestrian, and traffic sign detection in complex urban areas.

One of YOLOv8’s best improvements for ADAS is its resistance to varying light and weather conditions. Intelligent label assignment and an enhanced loss function enable more reliable detection under challenging conditions such as low light, rain, and occlusions—critical parameters for autonomous driving. The anchor-free methodology also reduces computational requirements, allowing YOLOv8 to run in real time on automotive devices.

Better situational awareness, collision mitigation, and road driver aid allow it to shine as a state-of-the-art object detection architecture for ADAS.

2.4. Performance Metrics

In object detection, the performance of these networks is often measured by the mean Average Precision (mAP), which calculates the area under the precision–recall curve. Other key metrics include Intersection Over Union (IoU), which measures the overlap between predicted bounding boxes and ground-truth boxes, and frames per second (FPS), which assesses how fast the model can process images. In Table 1 the fps and AP have been put up for some of the widely used object detection algorithms.

Table 1.

Comparison of object detection architectures [18,22,23].

2.5. Challenges in Object Detection and Tracking

Object detection and tracking in AVs must handle various challenging conditions, including occlusion, adverse weather, and nighttime.

2.5.1. Handling Occlusion in Tracking

Occlusion is a common challenge in which other objects temporarily block objects. This requires the tracking system to re-identify objects when they reappear. Algorithms like DeepSORT, BoT-SORT, and ByteTrack excel at maintaining object awareness even during occlusion. They use appearance-based and motion-based models to predict object locations.

2.5.2. Adverse Weather Conditions

Object detection becomes more complex in challenging weather conditions like rain or fog [24]. Rain droplets, for example, can obscure critical features. Research on de-raining techniques, including using GANs [25] (Generative Adversarial Networks), has shown that removing rain droplets improves visibility and can sometimes smooth out the image, reducing object detection accuracy as you can see in Table 2. A PReNet [26] was introduced, which iteratively trained a network dedicated to the dense image inpainting using the raindrop mask issued from the semi-supervised stage [26].

Table 2.

The AP for each class and mAP evaluated based on the AP values of the classes.

Other approaches include domain adaptation, where models trained in clear conditions are adapted to handle adverse conditions using unsupervised learning techniques. A very descriptive paper about the domain adaptation strategy for Faster R-CNN was written in [27].

2.5.3. Nighttime Object Detection

Low-light conditions present another significant challenge for AVs [28]. Nighttime detection suffers from issues like poor illumination and image noise. Recent studies have suggested that incorporating images from dusk and dawn into the training set helps improve the model’s robustness in low-light conditions. In Table 3 is a breakdown of images in the BDD dataset [29]. Refer to the Additionally, hardware solutions such as LiDAR, infrared (IR), and thermal cameras enhance detection performance in the dark.

Table 3.

Breakdown of BDD dataset.

2.6. Datasets for Object Detection and Tracking

Several datasets are widely used for benchmarking object detection and tracking models:

- KITTI Vision: one of the most comprehensive datasets for AVs, providing images and 3D point clouds for object detection and tracking.

- nuScenes: a large-scale dataset for AV research, including LiDAR, camera images, and radar data.

- Waymo Open Dataset: developed by Waymo, it provides extensive data for training object detection and tracking models.

- CityScapes: focuses on semantic segmentation and object detection in urban environments.

Accurate and efficient object tracking is critical to autonomous vehicle (AV) perception systems. It enables AVs to maintain situational awareness, make informed decisions, and ensure the vehicle’s and its surroundings’ safety. Tracking helps AVs monitor moving objects like vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists across consecutive frames, even when these objects are temporarily occluded. This section explores various object tracking algorithms, from older techniques to state-of-the-art methods, analyzing their strengths, limitations, and use cases, focusing on how they handle occlusion. In Table 4 are few of the most widely used dataset for object detection, tracking and segmentation for AV’s.

Table 4.

Datasets for autonomous vehicle perception.

Table 4.

Datasets for autonomous vehicle perception.

| Dataset | Real | Location Accuracy | Diversity | Annotation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D | 2D | Video | Lane | ||||

| CamVid [30] | ✓ | - | Daytime | No | Pixel: 701 | ✓ | 2D/2 classes |

| Kitti [31] | ✓ | cm | Daytime | 80k 3D box | Box: 15k, Pixel: 400 | - | No |

| Cityscapes [32] | ✓ | - | Daytime, 50 cities | No | Pixel: 25k | - | No |

| IDD [33] | ✓ | cm | Various weather, urban and rural roads in India | No | Pixel: 10k | ✓ | No |

| Mapillary [34] | ✓ | Meter | Various weather, day and night, 6 continents | No | Pixel: 25k | - | 2D/2 classes |

| BDD100K [29] | ✓ | Meter | Various weather, 4 regions in US | No | Box: 100k, Pixel: 10k | - | 2D/2 classes |

| SYNTHIA [35] | - | - | Various weather | Box | Pixel: 213k | No | No |

| P.F.B. [36] | - | - | Various weather | Box | Pixel: 250k | - | No |

| ApolloScape [37] | ✓ | cm | Various weather, daytime, 4 regions in China | 3D semantic point, 70k 3D fitted cars | Pixel: 140k | 3D/2D video | 35 classes |

| Waymo Open Dataset [38] | ✓ | cm | Various weather, urban and suburban roads in the US | 12 M 3D boxes | Box: 12M, Pixel: 200k | ✓ | 2D/3D lane markings |

Note: indicates real dataset and annotation in video available.

2.6.1. Classical Tracking Methods

Before the rise of deep learning, classical tracking methods, such as Kalman filtering and the Hungarian algorithm, were widely used. These methods operate based on mathematical models and object motion assumptions.

- Kalman filtering: This method is commonly used to estimate the future state of an object based on its past trajectory. The Kalman filter is beneficial for tracking objects moving in a linear path with constant velocity. However, it struggles in cases where the object’s movement is erratic or nonlinear.Example: In the context of AVs, a Kalman filter might track the position of a moving car on a highway by predicting its future location based on its current speed and direction [39].

- Hungarian algorithm: This algorithm solves the assignment problem—matching detected objects in consecutive frames. It assigns objects from the current frame to the closest objects detected in the next frame, minimizing the overall movement cost. This method can efficiently handle multiple objects but is limited by its reliance on spatial proximity, often failing in complex scenes with significant object overlap [39].

Despite their simplicity, these methods form the foundation of many modern tracking systems. They are computationally efficient but lack the robustness to handle more complex scenarios involving occlusion, appearance changes, or unpredictable object motion.

2.6.2. Deep Learning-Based Tracking

With the advent of deep learning, object tracking has become far more robust and capable of handling complex environments. Deep learning-based tracking algorithms incorporate both appearance-based and motion-based information, allowing them to manage occlusion, re-identify objects, and track through complex interactions. The following discussion explores deep learning-based tracking methods, highlighting their advancements in addressing tracking challenges. In support of this, Table 5 compares the performance of the SORT, DeepSORT, and ByteTrack methods using key tracking metrics.

- SORT (Simple Online and Realtime Tracking): SORT is an early and simple tracking algorithm that uses Kalman filtering for motion prediction and the Hungarian algorithm for object association. It tracks objects solely based on motion models without considering appearance information, which makes it susceptible to errors in crowded environments or occlusion [40].Use case: SORT is most effective in environments with minimal occlusion or interaction between objects, such as monitoring traffic in low-density areas.Limitation: the algorithm frequently loses track of objects during occlusions due to its sole reliance on motion models, which prevent it from distinguishing between objects based on appearance.

- DeepSORT (Simple Online and Realtime Tracking with Deep Appearance Descriptors): DeepSORT improves upon SORT by incorporating deep appearance descriptors from a convolutional neural network (CNN). This addition helps the algorithm distinguish objects based on their visual characteristics, improving its ability to maintain consistent tracking during occlusion and re-identification when objects reappear after being hidden.The improvement over SORT: using appearance-based features, DeepSORT is more robust in crowded scenes or environments where objects frequently overlap.Use case: DeepSORT is ideal for dense urban environments or crowded pedestrian areas, where the visual appearance of objects is critical to their accurate tracking.

- Tracktor: Tracktor is a tracking-by-detection algorithm that leverages object detection across multiple frames, eliminating the need for a separate tracking module. Instead, it uses bounding-box regression to predict an object’s future position, making the process more straightforward but dependent on high-quality object detection [41].Improvement over DeepSORT: Tracktor simplifies the tracking process by directly extending detection into future frames, though it relies heavily on the quality of the detection.Use case: Tracktor performs well in environments where the detection system is highly reliable, such as AVs equipped with advanced LiDAR or radar data for precise detection.

- BoT-SORT (Bytetrack Optimal Transport–SORT): BoT-SORT enhances DeepSORT by incorporating appearance and motion information while using Optimal Transport (OT) to match detected objects across frames. This leads to more accurate tracking, particularly in scenarios with rapid object movement or complex interactions between objects.The improvement over Tracktor: BoT-SORT integrates appearance information, allowing it to handle occlusion better than Tracktor, which relies solely on bounding-box predictions.Use case: BoT-SORT is especially useful in high-speed tracking scenarios, such as racing or drone footage, where objects move at varying speeds and directions.

- ByteTrack: ByteTrack improves upon tracking by utilizing high-confidence and low-confidence detection. This allows ByteTrack to track objects even when they are partially visible or occluded, reducing missed detection events and increasing overall robustness in challenging environments.An improvement over BoT-SORT: ByteTrack’s ability to incorporate low-confidence detection ensures continuous tracking even in scenarios with severe occlusion or partial visibility.Use case: ByteTrack is ideal for urban environments, where AVs must track multiple objects under varying conditions, such as dense city traffic or busy intersections.

Table 5.

Performance scores for SORT, DeepSORT, and ByteTrack. Source: [42].

Table 5.

Performance scores for SORT, DeepSORT, and ByteTrack. Source: [42].

| Metric | SORT | DeepSORT | ByteTrack |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOTA | 54.7% | 61.4% | 77.3% |

| MOTP | 77.5% | 79.1% | 82.6% |

| ID switches | 831 | 781 | 558 |

| MT | 34.2% | 45.1% | 54.7% |

| ML | 24.6% | 21.3% | 14.9% |

| FP | 7876 | 5604 | 3828 |

| FN | 26,452 | 21,796 | 14,661 |

| Processing speed | 143 FPS | 61 FPS | 171 FPS |

2.6.3. Occlusion Handling and Re-Identification

Occlusion occurs when an object is temporarily blocked from view by another object. This is a common challenge for AVs in real-world scenarios, as objects such as pedestrians or other vehicles often move behind obstacles. Handling occlusion requires advanced techniques to ensure tracking continuity and accurate re-identification once objects reappear.

- Appearance descriptors: Algorithms like DeepSORT use visual appearance features to help re-identify objects after they have been occluded. By capturing the unique visual characteristics of objects, these trackers can re-associate objects with their original identities when they reappear.

- Multiple detection strategies: Algorithms such as ByteTrack maintain tracking using high-confidence and low-confidence detection. This ensures that even when an object is partially visible or occluded, its trajectory can still be maintained through lower-confidence predictions.

- Re-identification models: In algorithms like OC-SORT and Tracktor, Re-ID models predict the object’s likely future location based on its previous movements. This helps reassign the object’s identity when it reappears after occlusion, reducing errors in tracking [43].

- Motion modeling and data association: Algorithms employ motion models such as Kalman filters to predict the future trajectory of an object based on its velocity and direction. This allows for consistent tracking even when objects are temporarily occluded.

Each object-tracking algorithm builds upon the limitations of its predecessor, offering improved performance in handling occlusion, re-identification, and object association. While simpler algorithms like SORT and DeepSORT work well in less complex environments, more advanced algorithms like ByteTrack and OC-SORT offer significant advantages in real-world, high-occlusion, and high-interaction environments. These advancements are essential for AVs to ensure safety and efficiency in real-time navigation.

3. Localization Strategies in Autonomous Vehicles

Localization is a very crucial part of the operation of autonomous vehicles. The vehicle can know its precise position, orientation, and velocity within the surrounding environment. It is achieved using various sensors and technologies to know exactly where the vehicle is, typically with a centimeter-level accuracy.

The latest advances in precise positioning allow vehicles to localize themselves to a few centimeters and position themselves concerning the road, lanes, and surroundings. This contextual perspective expands the outer horizons of the surroundings concerning the limited immediate view, aiding the vehicle in making intelligent choices like changing lanes, navigating intersections, or formulating a route plan [44]. Localization extends the context so that safety improvements become possible as risks of accidents decrease, and vehicles can anticipate and avoid hazards that have not yet become apparent. It increases safety through sensor fusion by integrating information through different types of sensors (including cameras, radar, and LiDAR) to overcome sensor-specific weaknesses, such as inconsistencies in the data from different sensors that signal possible problems. Localization also helps vehicles navigate other parameters like low light or inclement weather and even GNSS-denied situations [44]. In addition, it functions in conjunction with HD maps, which define the regions of the maps into which the vehicle is placed to guide its actions. It helps vehicles assimilate the position of roads and intersections not instantly within their line of sight, which would aid the vehicles in coping with unanticipated situations or failing sensors. It can be concluded that accurate localization is key to boosting the further development of autonomous driving systems.

3.1. Vision-Based Localization

Vision-based localization employs camera images to establish the position and orientation of self-driving vehicles concerning the environment. It analyses the imagery and retrieves particular perspectives in a plane relative to which the motion of the vehicle or its position is ascertained. It is efficient in areas where GPS signals cannot be obtained. It can also be used with other sensors such as IMUs, GNSS, and LiDAR for better performance and more encompassing solutions. Various methods of vision-based localization have shown usefulness in autonomous navigation, including feature-based approaches, visual odometry, and place recognition, among others. Nonetheless, issues such as sensitivity to lighting and texture still remain significant in its usage.

- Feature-based localization: In feature-based localization, differential features from a set of images are used to generate matches between consecutive frames for motion estimation purposes. Such a method is of great importance during such conditions, although chances of encountering such conditions where repetitive textures or low-contrast environments exist are also very high.

- Visual odometry (VO): Visual odometry (VO) concerns the self-location estimation of the mobile robot mounted with cameras or cameras mounted on their platforms [45]. VO has several advantages, such as escaping the GPS fold without compromising on the precision of positioning and being more affordable than other sensor-based systems. It is also less affected by wheel slippage, accommodating rough surfaces, unlike the old-fashioned wheel encoders [46]. However, there are some drawbacks that VO has to face, including the dependence on power resources and the processes of VO being affected by lighting and the environment in general, altering its effectiveness.

- Place recognition: Through place recognition, a person can recall a specific position that he/she has already been to by looking at the picture content. When used with other localization methods, this method can yield good positioning accuracy by enhancing the system’s robustness.

- Integration approaches: vision-based localization techniques usually have additional sensor systems that are used to improve performance.

GNSS/INS integration: combining vision data with inertial measurements can improve the accuracy and availability of positioning solutions.

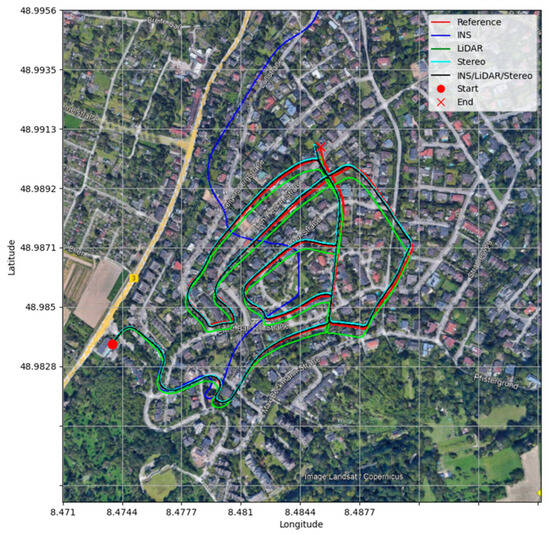

Sensor fusion: Fusing visual data with information from cameras, radar and LiDAR allows more reliable localization, particularly in GNSS-denied areas or challenging environments. Figure 3 shows the comparison of trajectories and the fusion of data from multiple sensors for precision navigation in GNSS-denied environments.

Figure 3.

Comparison of trajectories in the world frame (WGS84), D-34, base map captured from Google Earth. Source: [47].

Software-defined networking (SDN)-based smart-city approaches have been implemented recently with success to solve the problems of RNNs-based classification of Non-Line-of-Sight/Line-of-Sight (NLOS/LOS) and GNSS positioning in urban areas. Furthermore, dynamic sensor integration models based on environmental maps and multipath detection techniques have shown improved localization performance across various scenarios.

3.2. LiDAR-Based Localization

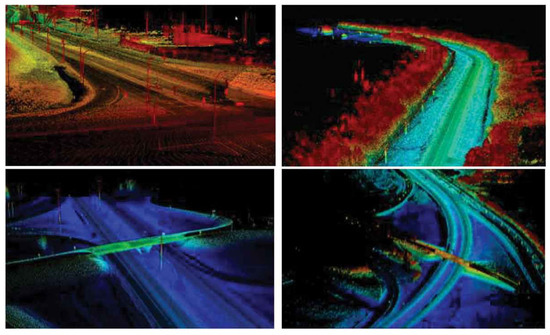

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) is becoming an important part of the machines mounted on the vehicle for autonomous navigation and has environmental sensing capabilities [48]. LiDAR does this by using a pulsed laser beam and measuring the time taken for the pulse to reflect after hitting a surface. This enables a high density of spatial information represented in the form of three-dimensional point clouds capturing the environment with millimeter precision [48].

Even in LiDAR-based localization, the 3D data described above help to find the accurate placement and direction of a car or robot in the surrounding space. This approach could be used where the conventional GPS would suffer, for example, in urban canyons, indoors, or other places with poor satellite visibility [48]. The localization task is solved by matching the current 3D LiDAR scan with a previously obtained high-resolution map of the area where the vehicle is located or with the map reconstructed along the vehicle track.

Point cloud registration algorithms are the cornerstone technology in localization. LiDAR systems are the principal technique of matching current LiDAR scans with some reference data to understand the vehicle’s position and heading. The purpose of these algorithms is to establish the best possible transformation for the alignment of two point clouds; one becomes the source (or the present scan) and the other the target [49]. One of the most efficient and simple techniques that has been found to be extensively applicable is the Iterative Closest Point algorithm. The ICP algorithm is based on an iterative improvement of point cloud alignments. Each iterative process includes two steps: the first matches point from the source and target cloud, and the second finds a transformation matrix used to rotate the source cloud [44]. This procedure is repeated till either the alignment remains unchanged, or the predetermined iteration number is reached [49].

That being said, ICP suffers from poor performance under initial misalignment, and due to the nature of the solution space in computer vision applications with repetitive structure, it gets stuck in the local optimum. In order to remove those limitations, a sufficient number of ICP variants are proposed as well. These include Point-to-Plane ICP aimed at speeding up the process by reducing the distance from a given point to the tangent plane associated with its nearest point, while Generalized ICP is a more comprehensive system that integrates both point-to-group and point-to-thin-object methods of operation into generalized point cloud matching models. Another variant, Trimmed ICP, improves robustness to outliers by considering only a subset of the best correspondences in each iteration [49].

A different alternative to ICP is the Normal Distributions Transform (NDT), which is a more advanced point cloud registration algorithm. NDT is a particular way of solving this problem in which the surrounding environment is modeled by a set of normal distributions. The point cloud is partitioned into voxels, and mean and covariance are computed for the ten points in a voxel. NDT focuses on optimizing the transformation to maximize the probability of the observed point cloud under the derived distributions. This way of areas is beneficial because even though ICP may be affected by the operational environment, the initial misalignment does not affect the technique’s robustness [49]. The downside is that NDT can be computationally heavy during the first stages as there is a requirement to compute normal distributions for every voxel.

The objective of the present invention is to outline the fundamental features of an approach for developing mobile navigation systems based on a LiDAR sensor framework. One of the main advantages of photogrammetry based on laser scanning is its insensitivity to light changes. In contrast with the systems based on cameras, LiDAR is unaffected by the time of day or the weather (up to a certain severity) and operates even in the dark. Moreover, thanks to the precision of LiDAR, good positioning is also accessible in built-up areas where other sensor approaches struggle with spatial ambiguity with all the relative structures [48].

Nevertheless, LiDAR-based localization also has its disadvantages. For instance, it can be quite challenging to manage the real-time processing of dense point clouds due to their high computational demand, which is why strong algorithms and efficient onboard computing are required. In addition, a structural modification of the environment with an emphasis on partial occlusions or dynamic obstacles needs to be strictly controlled to prevent localization inaccuracies. Thus, a number of researchers focus their efforts on these elements and work on increasing the reliability of LiDAR-based localization in the presence of dynamic factors.

Additionally, important enhancements have been made to systems relying on LiDAR, such as solid-state LiDAR, improved sensor resolution and ranging, pushing the spatial resolution of the LiDAR-enhanced localization systems to a higher level. This approach is also being actively pursued to provide more effective and versatile localization capabilities for self-driving cars and other robotic devices by combining it with other sensors, like cameras and IMUs.

6. Challenges

The deployment of autonomous vehicles (AVs) in real-world environments presents several challenges that impact perception, localization, and mapping. While advancements in deep learning, sensor fusion, and mapping techniques have significantly improved AV performance, achieving full autonomy remains a complex task due to numerous obstacles. These challenges arise from the dynamic and unpredictable nature of road environments, sensor limitations, high computational demands, and ethical concerns.

To systematically identify and analyze these challenges, we conducted an extensive review of the existing literature, experimental evaluations, and real-world case studies. Our approach involved examining the limitations of state-of-the-art object detection, tracking, and localization techniques, as well as analyzing dataset biases and the impact of environmental conditions on AV performance. Additionally, we assessed computational constraints in real-time processing, and we considered the difficulties in integrating multiple sensor technologies and the scalability challenges in adapting AV systems to diverse geographical and infrastructural settings.

The following points outline the key challenges that hinder the widespread adoption and operational reliability of AVs. Each challenge is discussed in detail, highlighting its effects on perception, localization, and mapping.

- Dynamism and unpredictability: in an ideal world, all roads would be wide enough to accommodate intentionally designed cars that automatically transport passengers; we would need to consider scenarios where there are construction sites, other vehicles, or even pedestrians that do not interact directly with the car sensors; therefore, to receive uninterrupted traffic data, extensive autonomous navigation would have to be put into practice.

- Weather and lighting conditions: Autonomous systems can receive more accurate data in optimal conditions, although this is not always the case, whether we are looking at weather conditions such as rain, snow, or general overcast skies or the time of day reducing sensor efficiency. Even with models such as GAN or thermal sensors being developed, the weather is still critical to automatic navigation.

- Occlusion and re-identification: Having to manually follow certain features across frames for tracking is strenuous, especially in the case of occlusion, whereby one or multiple tracked objects are surrounded by other objects. Although specific models such as DeepSORT or ByteTrack are effective for operational environments with fewer people, they are not mainly designed for complex environments.

- High computational demands: High standards such as real-time output when performing a variety of tasks, including identifying and mapping objects from three-dimensional sensors, are now theoretically possible. However, this would require spending a large sum of money on advanced hardware, making it inaccurate in predicting real-life scenarios.

- Data bias: Datasets such as KITTI, nuScenes, and Waymo Open Dataset are being used to train autonomous vehicle models. Although these datasets are pretty broad, they may also be limited in geographical coverage, weather conditions, and social culture, which can hinder the model, especially in places where such conditions exist.

- Cybersecurity risks: The fact that AVs are constantly communicating with each other, transmitting updates of maps and feedback of sensors, makes them more prone to cyber-attacks. Navigation, privacy, and even vehicle collision can be controlled by hacked devices, which is why robust systems are required to maintain security.

- Fusion of different technologies: Integrating AI technologies such as cameras, LiDAR, radar, and GNSS is challenging. Each sensor comes with its own set of limitations, and amalgamating their outputs to form a single system requires sophisticated algorithms for sensor fusion that are both computationally efficient and robust.

- Legal and social issues: Laws have not been made to adapt to the advancements in technology, and this causes a lack of safety standards and regulations in case a vehicle ends up being involved in an accident. Ethical problems arise when a decision needs to be made in an unavoidable accident, which makes the integration of AVs more difficult.

- Scalability and deployment in untouched or remote areas: Existing AV technologies are built around large cities and flirt with the suburbs with amenities such as lane markings and HD maps. Adapting such systems to rural or cross-country operations is still an uphill task due to sparse data availability and weak sensors in unpaved areas.

7. Discussion and Future Scope

As autonomous vehicle (AV) technology advances, several key challenges and opportunities shape its development. While significant progress has been made in perception, localization, and mapping, real-world deployment remains hindered by sensor limitations, computational demands, data biases, and cybersecurity concerns. This study evaluated various methodologies to determine their effectiveness in addressing these challenges, revealing both strengths and areas for improvement.

One major finding is that deep learning-based perception models, such as YOLOv8, Faster R-CNN, and SSD, perform well in structured environments but struggle in complex scenarios involving occlusion, low lighting, and adverse weather conditions. While tracking algorithms like ByteTrack and BoT-SORT demonstrate strong object re-identification capabilities, their performance declines in dense and unpredictable traffic conditions. These results emphasize the need for enhanced sensor fusion techniques that integrate data from LiDAR, radar, and cameras to improve object detection accuracy under varying environmental conditions.

In localization and mapping, our results confirm that LiDAR-SLAM and HD mapping provide superior accuracy compared to camera-based methods, particularly in GPS-denied environments. However, a critical limitation observed was the reliance on preexisting HD maps, which can quickly become outdated in dynamic urban settings. SLAM-based mapless navigation, leveraging real-time updates, emerges as a promising alternative, but its success depends on loop closure detection, real-time optimization, and computational efficiency. To enhance scalability, sensor fusion combining LiDAR, IMU, and GNSS proves to be the most reliable localization strategy, balancing accuracy with adaptability.

A notable challenge in AV adoption is dataset diversity. Current training datasets, including KITTI, nuScenes, and Waymo Open Dataset, exhibit geographic and environmental biases, limiting their generalization to rural, extreme weather, and culturally different driving conditions. Expanding dataset coverage and incorporating synthetic data generation through Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can improve AV adaptability across diverse scenarios.

Another critical area of concern is computational efficiency. High-performing models often require significant processing power, making real-time deployment challenging, especially for cost-sensitive applications. The integration of 5G and edge computing can alleviate onboard processing burdens by offloading computational tasks, enabling faster decision-making while reducing hardware constraints. However, as connectivity increases, cybersecurity and data privacy risks must be addressed to prevent threats such as data breaches, GPS spoofing, and man-in-the-middle attacks. Strengthening data encryption and multi-signature authentication protocols is crucial for ensuring secure AV communications.

Beyond technological advancements, the ethical, regulatory, and societal aspects of AV deployment must be considered. Establishing industry-wide safety regulations, liability frameworks, and ethical decision-making models will be essential for public trust and large-scale adoption. Additionally, AV technology holds potential beyond urban mobility, with applications in agriculture, mining, and logistics, where automated off-highway systems can enhance efficiency and safety.

Overall, our findings highlight the importance of adaptive AI models, robust sensor fusion, real-time SLAM, and secure AV networks in shaping the next generation of autonomous navigation systems. Addressing these challenges while leveraging emerging technologies will ensure that AVs are not only scalable and efficient but also capable of navigating safely in complex, real-world environments.

8. Conclusions

Object detection, tracking, localization, and mapping techniques are continuously evolving, leading to augmented performance in autonomous navigation. The survey discussed key algorithms that ranged from classical methods to deep learning techniques, as well as the synergetic role of sensor fusion, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), SLAM, and high-definition maps in achieving robust autonomous navigation.

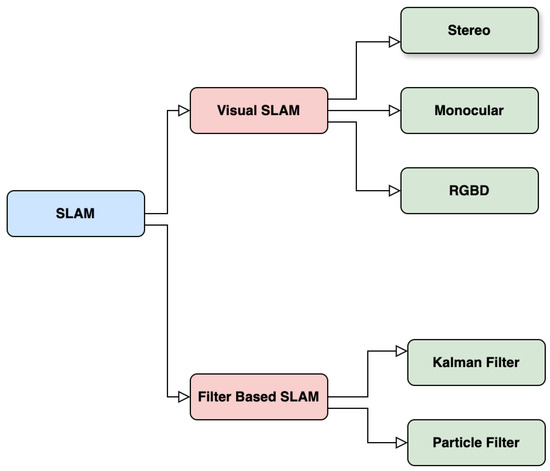

Yet, despite these gigantic advances, research in the area is still ongoing, addressing problems posed by occlusions, adverse weather conditions, and speed efficiency. The comparison between map-based and mapless navigation strategies sheds light on a tendency toward making the system more adaptive to real-time input while minimizing the dependency on prebuilt map specifications, augmented by improvements in SLAM techniques, including Kalman and particle filters, to increase localization accuracy in dynamic environments.

Future studies ought to develop farther efficient, smart, and big solutions combining real-time perception with virtually no computational expense. There should be a fruitful collaboration between academia and industry if we plan to deploy autonomous vehicles on a massive scale to address the limitations arising from existing systems and consequently operationalize complete, safe, and reliable systems of autonomous navigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.P., B.P., H.G., N.S.M. and S.R.; methodology, validation, investigation and writing—original draft preparation, B.P., H.G., N.S.M. and S.R.; writing—review and editing, A.K.P.; supervision, and project administration, A.K.P. and P.B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by PES University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7263–7271. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; pp. 3645–3649. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Bytetrack: Multi-object tracking by associating every detection box. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayarajan, V.; Rajeshkannan, R.; Rajkumar Dhinakaran, R. Automatidetection of moving objects using Kalman algorithm. Int. J. Pharm. Technol. IJPT 2016, 8, 18963–18970. [Google Scholar]

- Aharon, N.; Orfaig, R.; Bobrovsky, B.Z. BoT-SORT: Robust associations multi-pedestrian tracking. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.14651. [Google Scholar]

- Grisetti, G.; Kümmerle, R.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. A tutorial on graph-based SLAM. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2010, 2, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lu, Z.; Lin, X. Vision-based environmental perception for autonomous driving. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2025, 239, 39–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Ma, H.; Zhao, L.; Xie, X.; Hua, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y. Vehicle Detection Algorithms for Autonomous Driving: A Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turay, T.; Vladimirova, T. Toward performing image classification and object detection with convolutional neural networks in autonomous driving systems: A survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 14076–14119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1504.08083. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Li, Y.; He, K.; Sun, J. R-fcn: Object detection via region-based fully convolutional networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Proceedings, Part V 13. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Iandola, F.; Jin, P.H.; Keutzer, K. Squeezedet: Unified, small, low power fully convolutional neural networks for real-time object detection for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, K.; Bai, S.; Xie, L.; Qi, H.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. CenterNet: Keypoint Triplets for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Hnewa, M.; Radha, H. Object detection under rainy conditions for autonomous vehicles: A review of state-of-the-art and emerging techniques. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2020, 38, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, R.; Tan, R.T.; Yang, W.; Su, J.; Liu, J. Attentive generative adversarial network for raindrop removal from a single image. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 2482–2491. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, D.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, P.; Meng, D. Progressive image deraining networks: A better and simpler baseline. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3937–3946. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Sakaridis, C.; Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. Domain adaptive faster r-cnn for object detection in the wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 3339–3348. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Parsi, A.; Mullins, D.; Horgan, J.; Ward, E.; Eising, C.; Denny, P.; Deegan, B.; Glavin, M.; Jones, E. A Study on Data Selection for Object Detection in Various Lighting Conditions for Autonomous Vehicles. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Xian, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Madhavan, V.; Darrell, T. Bdd100k: A diverse driving dataset for heterogeneous multitask learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 2636–2645. [Google Scholar]

- Brostow, G.J.; Fauqueur, J.; Cipolla, R. Semantic object classes in video: A high-definition ground truth database. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2009, 30, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The kitti dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 3213–3223. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, G.; Subramanian, A.; Namboodiri, A.; Chandraker, M.; Jawahar, C. IDD: A dataset for exploring problems of autonomous navigation in unconstrained environments. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 7–11 January 2019; pp. 1743–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhold, G.; Ollmann, T.; Rota Bulo, S.; Kontschieder, P. The mapillary vistas dataset for semantic understanding of street scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 4990–4999. [Google Scholar]

- Ros, G.; Sellart, L.; Materzynska, J.; Vazquez, D.; Lopez, A.M. The synthia dataset: A large collection of synthetic images for semantic segmentation of urban scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 3234–3243. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, S.R.; Hayder, Z.; Koltun, V. Playing for benchmarks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2213–2222. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Cheng, X.; Geng, Q.; Cao, B.; Zhou, D.; Wang, P.; Lin, Y.; Yang, R. The apolloscape dataset for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 954–960. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Kretzschmar, H.; Dotiwalla, X.; Chouard, A.; Patnaik, V.; Tsui, P.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chai, Y.; Caine, B.; et al. Scalability in perception for autonomous driving: Waymo open dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 2446–2454. [Google Scholar]

- Tithi, J.J.; Aananthakrishnan, S.; Petrini, F. Online and Real-time Object Tracking Algorithm with Extremely Small Matrices. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.12091. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar, V.H.; Roche, D.G.; Gingins, S. Tracktor: Image-based automated tracking of animal movement and behaviour. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelyazid, M. Comparative Evaluation of SORT, DeepSORT, and ByteTrack for Multiple Object Tracking in Highway Videos. Int. J. Sustain. Infrastruct. Cities Soc. 2023, 8, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Yang, L.; Meng, D.; Zhou, X.; Fan, H.; Zhang, L. AttMOT: Improving multiple-object tracking by introducing auxiliary pedestrian attributes. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 5454–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcon, N. DRIVE Labs: How Localization Helps Vehicles Find Their Way | NVIDIA Technical Blog. 2022. Available online: https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/drive-labs-how-localization-helps-vehicles-find-their-way/ (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Azzam, R.; Taha, T.; Huang, S.; Zweiri, Y. Feature-based visual simultaneous localization and mapping: A survey. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, L.R.; Ricardo, N.M.; Pereira, M.I.; Hiolle, A.; Pinto, A.M. A practical survey on visual odometry for autonomous driving in challenging scenarios and conditions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 72182–72205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, N.; El-Rabbany, A. INS/LIDAR/Stereo SLAM Integration for Precision Navigation in GNSS-Denied Environments. Sensors 2023, 23, 7424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Xu, X.; Lu, S.; Chen, X.; Xiong, R.; Shen, S.; Stachniss, C.; Wang, Y. A survey on global lidar localization: Challenges, advances and open problems. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 3139–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yin, Y.; Jing, Q. Comparative analysis of 3D LiDAR scan-matching methods for state estimation of autonomous surface vessel. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golledge, R.G.; Gärling, T. Cognitive maps and urban travel. In Handbook of Transport Geography and Spatial Systems; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2004; pp. 501–512. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, R.A.; Patai, E.Z.; Julian, J.B.; Spiers, H.J. The cognitive map in humans: Spatial navigation and beyond. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1504–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wang, R.; He, B.; Lu, F.; Xu, Y. Compact and efficient topological mapping for large-scale environment with pruned Voronoi diagram. Drones 2022, 6, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlinson, D.; Jarvis, R. Topologically-directed navigation. Robotica 2008, 26, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, V.; Chiu, H.P.; Samarasekera, S.; Kumar, R.T. Utilizing semantic visual landmarks for precise vehicle navigation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Yokohama, Japan, 16–19 October 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, J.; Montemerlo, M.; Thrun, S. Map-based precision vehicle localization in urban environments. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 27–30 June 2007; Volume 4, pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sundar, K.; Srinivasan, S.; Misra, S.; Rathinam, S.; Sharma, R. Landmark Placement for Localization in a GPS-denied Environment. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual American Control Conference (ACC), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 27–29 June 2018; pp. 2769–2775. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ruichek, Y. Occupancy grid mapping in urban environments from a moving on-board stereo-vision system. Sensors 2014, 14, 10454–10478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, A.; Wurm, K.M.; Bennewitz, M.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. OctoMap: An efficient probabilistic 3D mapping framework based on octrees. Auton. Robot. 2013, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leven, J.; Corso, J.; Cohen, J.; Kumar, S. Interactive visualization of unstructured grids using hierarchical 3D textures. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Volume Visualization and Graphics, Boston, MA, USA, 28–29 October 2002; pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lafarge, F.; Mallet, C. Creating large-scale city models from 3D-point clouds: A robust approach with hybrid representation. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2012, 99, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; Howard, A.; Sukhatme, G.S. Towards geometric 3D mapping of outdoor environments using mobile robots. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2–6 August 2005; pp. 1507–1512. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi Soorchaei, B.; Razzaghpour, M.; Valiente, R.; Raftari, A.; Fallah, Y.P. High-definition map representation techniques for automated vehicles. Electronics 2022, 11, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghazaly, G.; Frank, R.; Harvey, S.; Safko, S. High-definition maps: Comprehensive survey, challenges and future perspectives. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 4, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrat, K.T.; Cho, H.J. A Comprehensive Survey on High-Definition Map Generation and Maintenance. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charroud, A.; El Moutaouakil, K.; Palade, V.; Yahyaouy, A.; Onyekpe, U.; Eyo, E.U. Localization and Mapping for Self-Driving Vehicles: A Survey. Machines 2024, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Gu, Y.; Kamijo, S. Mapping for autonomous driving: Opportunities and challenges. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2020, 13, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Z.; Chen, Q.; Niu, X. High-accuracy positioning in urban environments using single-frequency multi-GNSS RTK/MEMS-IMU integration. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhao, Q.; Verhagen, S.; Psychas, D.; Liu, X. Assessing the performance of multi-GNSS PPP-RTK in the local area. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldibaja, M.; Suganuma, N.; Yoneda, K.; Yanase, R. Challenging environments for precise mapping using GNSS/INS-RTK systems: Reasons and analysis. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargoum, S.A.; Basyouny, K.E. A literature synthesis of LiDAR applications in transportation: Feature extraction and geometric assessments of highways. GISci. Remote Sens. 2019, 56, 864–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blochliger, F.; Fehr, M.; Dymczyk, M.; Schneider, T.; Siegwart, R. Topomap: Topological mapping and navigation based on visual slam maps. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 3818–3825. [Google Scholar]

- Drouilly, R.; Rives, P.; Morisset, B. Semantic representation for navigation in large-scale environments. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 1106–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpakeaw, S.; Dillmann, R. Semantic road maps for autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the Autonome Mobile Systeme 2007: 20. Fachgespräch Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern, Germany, 18–19 October 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Map Rendering | Mapping Technology | Platform | HERE. Available online: https://www.here.com/platform/map-rendering (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- HD Map | TomTom. Available online: https://www.tomtom.com/products/orbis-maps-for-automation/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Berrio, J.S.; Ward, J.; Worrall, S.; Nebot, E. Identifying robust landmarks in feature-based maps. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Paris, France, 9–12 June 2019; pp. 1166–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.; Cho, S.; Sunwoo, M.; Jo, K. Crowd-sourced mapping of new feature layer for high-definition map. Sensors 2018, 18, 4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtes, M.; Westhofen, L.; Turner, L.R.; Lotto, K.; Schuldes, M.; Weber, H.; Wagener, N.; Neurohr, C.; Bollmann, M.H.; Körtke, F.; et al. 6-Layer Model for a Structured Description and Categorization of Urban Traffic and Environment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59131–59147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyants, V.; Romanov, A. An Object-Oriented Approach to a Structured Description of Machine Perception and Traffic Participant Interactions in Traffic Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 7th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Engineering (ICITE), Beijing, China, 11–13 November 2022; pp. 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhashash, M.; Albanwan, H.; Qin, R. A review of mobile mapping systems: From sensors to applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.F.; Chiang, K.W.; Tsai, M.L.; Lee, P.L.; Zeng, J.C.; El-Sheimy, N.; Darweesh, H. The implementation of semi-automated road surface markings extraction schemes utilizing mobile laser scanned point clouds for HD maps production. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.W.; Hsu, C.C.; Wang, W.Y. Cost effective mobile mapping system for color point cloud reconstruction. Sensors 2020, 20, 6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilci, V.; Toth, C. High definition 3D map creation using GNSS/IMU/LiDAR sensor integration to support autonomous vehicle navigation. Sensors 2020, 20, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Elallid, B.; Benamar, N.; Senhaji Hafid, A.; Rachidi, T.; Mrani, N. A Comprehensive Survey on the Application of Deep and Reinforcement Learning Approaches in Autonomous Driving. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 7366–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardeau-Montaut, D. CloudCompare—Open Source Project—danielgm.net. Available online: https://www.danielgm.net/cc/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Gholami Shahbandi, S.; Magnusson, M. 2D map alignment with region decomposition. Auton. Robot. 2019, 43, 1117–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, R.; Zheng, H. Road curb extraction from mobile LiDAR point clouds. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 55, 996–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; McElhinney, C.P.; Lewis, P.; McCarthy, T. An automated algorithm for extracting road edges from terrestrial mobile LiDAR data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 85, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, H.; Wang, B.; An, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z. Voxel-FPN: Multi-scale voxel feature aggregation for 3D object detection from LIDAR point clouds. Sensors 2020, 20, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Olson, E.B. Extracting general-purpose features from LIDAR data. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, Alaska, 3–8 May 2010; pp. 1388–1393. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, H.; Song, Y.; Yu, B.; Niu, R. Fusionlane: Multi-sensor fusion for lane marking semantic segmentation using deep neural networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 23, 1543–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Yu, X.; Hu, H. Interactive attention learning on detection of lane and lane marking on the road by monocular camera image. Sensors 2023, 23, 6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, P.; Xu, Z.; Min, H.; Yu, H. Fusion of 3D LIDAR and camera data for object detection in autonomous vehicle applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 4901–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, X.; Song, X.; Li, H.; Tao, W. Lif-seg: Lidar and camera image fusion for 3d lidar semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagahit, M.L.R.; Matsuoka, M. Focal Combo Loss for Improved Road Marking Extraction of Sparse Mobile LiDAR Scanning Point Cloud-Derived Images Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.S.; Moore, D.; Antone, M.; Olson, E.; Teller, S. Finding multiple lanes in urban road networks with vision and lidar. Auton. Robot. 2009, 26, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Cao, X.; Tang, K.; Cao, Z.; Sizikova, E.; Zhou, T.; Li, E.; Liu, A.; Zou, S.; Yan, X.; et al. High-definition map automatic annotation system based on active learning. AI Mag. 2023, 44, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Hdmapnet: An online hd map construction and evaluation framework. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 4628–4634. [Google Scholar]

- Elhousni, M.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, X. Automatic building and labeling of hd maps with deep learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 13255–13260. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Jiang, S.; Liang, X.; Wang, N.; Song, S. Diff-net: Image feature difference based high-definition map change detection for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 2635–2641. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J. Real-time HD map change detection for crowdsourcing update based on mid-to-high-end sensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, K.; Kim, C.; Sunwoo, M. Simultaneous localization and map change update for the high definition map-based autonomous driving car. Sensors 2018, 18, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, I.P.; Llorca, D.F.F.; Gavilan, M.; Pardo, S.Á.Á.; García-Garrido, M.Á.; Vlacic, L.; Sotelo, M.Á. Accurate global localization using visual odometry and digital maps on urban environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2012, 13, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.M.; Yoon, T.S.; Kim, E.; Park, J.B. Lane-level map-matching method for vehicle localization using GPS and camera on a high-definition map. Sensors 2020, 20, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.; Alsweiss, S.; Toker, O.; Razdan, R.; Santos, J. An overview of autonomous vehicles sensors and their vulnerability to weather conditions. Sensors 2021, 21, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; You, X.; Chen, L.; Tian, J.; Tang, F.; Zhang, L. A scalable and accurate de-snowing algorithm for LiDAR point clouds in winter. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, F.; Kishimoto, N.; Okada, Y.; Che, W. Creation of high definition map for autonomous driving. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 43, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Venkatramani, S.; Paz, D.; Li, Q.; Xiang, H.; Christensen, H.I. Probabilistic semantic mapping for autonomous driving in urban environments. Sensors 2023, 23, 6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

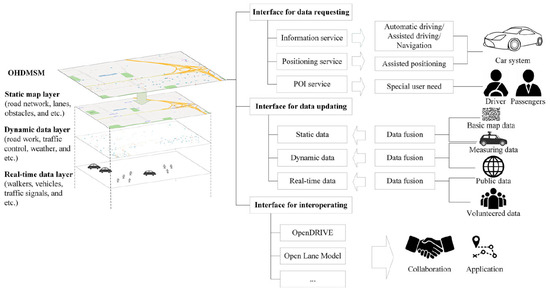

- Zhang, F.; Shi, W.; Chen, M.; Huang, W.; Liu, X. Open HD map service model: An interoperable high-Definition map data model for autonomous driving. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 2089–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.C.; Tartavull, I.; Bârsan, I.A.; Wang, S.; Bai, M.; Mattyus, G.; Homayounfar, N.; Lakshmikanth, S.K.; Pokrovsky, A.; Urtasun, R. Exploiting sparse semantic HD maps for self-driving vehicle localization. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 3–8 November 2019; pp. 5304–5311. [Google Scholar]

- Barsi, A.; Poto, V.; Somogyi, A.; Lovas, T.; Tihanyi, V.; Szalay, Z. Supporting autonomous vehicles by creating HD maps. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2017, 16, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeihagh, A.; Lim, H.S.M. Governing autonomous vehicles: Emerging responses for safety, liability, privacy, cybersecurity, and industry risks. Transp. Rev. 2019, 39, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, V.; Zámečník, P.; Havlíčková, D.; Pai, C.W. Human factors in the cybersecurity of autonomous vehicles: Trends in current research. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, S.; Ward, P.; Wilson, K.; Miller, J. Cyber threats facing autonomous and connected vehicles: Future challenges. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 18, 2898–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Lam, K.Y.; Tavva, Y. Autonomous vehicle: Security by design. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 7015–7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ryu, J.H. Autonomous Vehicle Localization Without Prior High-Definition Map. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 2888–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaviv, I. Benefits of Mapless Autonomous Driving Technology; Imagry—AI Mapless Autonomous Driving Software Company: San Jose, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guzel, M.S.; Bicker, R. A behaviour-based architecture for mapless navigation using vision. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2012, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Hein, B.; Bakr, M.; Schildbach, G.; Abel, B.; Rueckert, E. Using deep reinforcement learning with automatic curriculum learning for mapless navigation in intralogistics. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Sim-to-real: Mapless navigation for USVs using deep reinforcement learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, M.I.; Tan, S.Y.; Abdullah, A. Vision-based autonomous vehicle systems based on deep learning: A systematic literature review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baten, S.; Lutzeler, M.; Dickmanns, E.D.; Mandelbaum, R.; Burt, P.J. Techniques tor autonomous, off-road navigation. IEEE Intell. Syst. Their Appl. 1998, 13, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]