Preserving Privacy of Internet of Things Network with Certificateless Ring Signature

Abstract

1. Introduction

- This paper first proposes a CLRS scheme based on a lattice assumption. This CLRS scheme utilizes the bimodal Gaussian distribution to improve the key generation efficiency, a certificateless mechanism to weaken the centralized risk of KGC, and a ring signature mechanism to achieve unconditional anonymity.

- This paper presents a formal security proof of the proposed CLRS scheme in a random oracle model. The results show that this CLRS achieves unforgeability and anonymity. Meanwhile, an additional analysis also shows that it features non-repudiation, traceability, and anti-quantum security.

- This paper provides a comparative analysis and performance evaluation of the proposed CLRS scheme. The results show that this CLRS scheme is more efficient and practical than related schemes in strengthening IoT network security.

2. Related Work

2.1. Privacy-Preserving in IoT Network

2.2. Post-Quantum Cryptography for IoT Network

2.3. Lattice-Based Signature for IoT Network

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Lattice Theory

3.2. Model Definitions

- Setup (): Initiate a security parameter n; KGC generates the system parameters .

- Partial KeyGen. (): KGC utilizes the to generate the partial public and secret key pair for a new user.

- KeyExt. (): User utilizes , , and to derive their public and secret key pair .

- Sign (): User utilizes , , and to sign the message and output a signature .

- Verify (): Verifier utilizes , , and to verify the validity of signature , Then, outputs are accepted or rejected.

- Initialize: C initiates the system parameters .

- Query: E performs the following queries with C and tries to obtain enough information to increase the probability of forging a legitimate signature.

- –

- Partial secret key query: E queries the non-target user i about the partial private key .

- –

- Secret key query: E queries the non-target user i about the private key .

- –

- H query: E queries the non-target message about the hash algorithm H.

- –

- Signature query: E queries the non-target message about its signature

- Forge: E utilizes the information obtained to forge a signature of the target message .

- Challenge: C also can generate a signature of the target message via the forking lemma [25]. Then, C attempts to utilize these two signatures, and , to solve the instance.

- Analyze: Analyze whether the problem can be solved or not. Meanwhile, the successful forgery probability can be computed, and the security-proof results are confirmed.

- Initialize: C initiates the system parameters .

- Query: E performs the queries with C about the partial secret key, secret key, H, and signature.

- User creation: E creates two different users, and .

- Signature construction: C generates a signature for the target message by randomly selecting one user: or .

- Guess: With the former query results, E guesses to determine whether the signature is generated by user or .

- Analyze: With enough guess results, C analyzes the advantages of and probability that E can make the correct guess.

4. The Proposed CLRS

| Algorithm 1 Partial KeyGen. |

|

| Algorithm 2 KeyExt. |

|

| Algorithm 3 Sign |

|

| Algorithm 4 Verify |

|

5. Security Analysis

5.1. Correctness

5.2. Unforgeability

- Initialize: C initiates the system parameters .

- Query: E performs the following queries with C and tries to obtain enough information to increase the probability of forging a legitimate signature.

- –

- Partial secret key query: E queries non-target user i about partial private key . C first checks a dedicated list to see if the queried exists or not. If so, C returns to E. Otherwise, C executes the algorithm to derive a new and returns it to E. Meanwhile, C records this partial private key in the list . Here, E can perform this query with times until obtaining enough information.

- –

- Secret key query: E queries non-target user i about private key . C first checks a dedicated list to see if the queried exists or not. If so, C returns to E. Otherwise, C executes the algorithm to derive a new and returns it to E. Note that if the partial private key is not queried, C must perform the algorithm first and record this result in the list . Meanwhile, C records this private key in list . Here, E can perform this query with times until obtaining enough information.

- –

- H query: E queries the non-target message about the hash algorithm H. C first checks a dedicated list to see if the queried exists or not. If so, C returns to E. Otherwise, C executes the first three steps of the algorithm to derive a new hash value and returns it to E. Meanwhile, C records this private key in list . Here, E can perform this query with times until obtaining enough information.

- –

- Signature query: E queries the non-target message about its signature . C first checks a dedicated list to see if the queried exists or not. If so, C returns to E. Otherwise, C executes steps 4 and 5 of the algorithm to derive a new signature and returns it to E. Note that if the hash value and the private key are not queried, C must perform the H algorithm and algorithm first and record these results in lists and , respectively. Meanwhile, C records this signature in list . Here, E can perform this query with times until obtaining enough information.

- Forge: With enough queried information, E has the ability to forge a secret key and then generate a valid signature of target message .

- Challenge: As C grasps the users’ public and private keys from the former query processes, C can perform the signing process correctly. Based on the forking lemma, C can generate the other one valid signature of the same target message . So, signature of target message and the forged signature satisfy the following Equation (6):

- Analyze: C performs a detailed analysis of Equation (6) and tries to solve the instance. Equation (6) can be changed to Equation (7).Then, we can derive Equation (9) when the first equation is subtracted from the second equation in Equation (8).Therefore, we can derive as . According to Definition 4, is a solution of the instance . Now, C has successfully solved the hard lattice problem.However, the problem cannot be solved with the most advanced computation, so the fact that C solved this problem is contrary to fact. So, the former hypothesis that E can successfully forge a valid CLRS is invalid, and the proposed CLRS cannot be forged by an adversary. Meanwhile, along with the increased query times, the successful forgery probability of E decreases. In the former query–response game, E performed partial secret key queries, secret queries, hash queries, and signature queries, so the probability should be . Here, is due to the assumption that C has a chance of returning back to the former query. In terms of probability, E cannot forge a valid CLRS, and the proposed CLRS scheme is secure.

5.3. Signer’s Anonymity

- User creation: E randomly selects two users, and , and asks the challenger C to generate the corresponding signatures.

- Signature construction: C executes the CLRS scheme and generates a signature by randomly selecting user . When he selects , he generates signature with keys . When he selects , he generates signature with keys . Then, he sends the generated signature to E.

- Guess: When E receives signature , E performs a guess or . Next, C publishes the correct results. Here, E presents correct results with a probability of .

- Analysis: First and foremost, this signature is constructed with the lattice assumption . E cannot solve this lattice hard problem and cannot obtain any information about the keys (or ) that C selects for signing. Secondly, the parameter is chosen with a bimodal Gaussian distribution , and this distribution is uniform. So, every selection is different, and E cannot obtain any information from other former generated signatures. Then, the bit in the signing process is selected randomly, which also guarantees the uncertainty of the signature at every signing time. Therefore, the statistical distance between two signatures and is also indistinguishable, and the probability of success is for E each time.

5.4. Other Security Properties

6. Efficiency Comparison

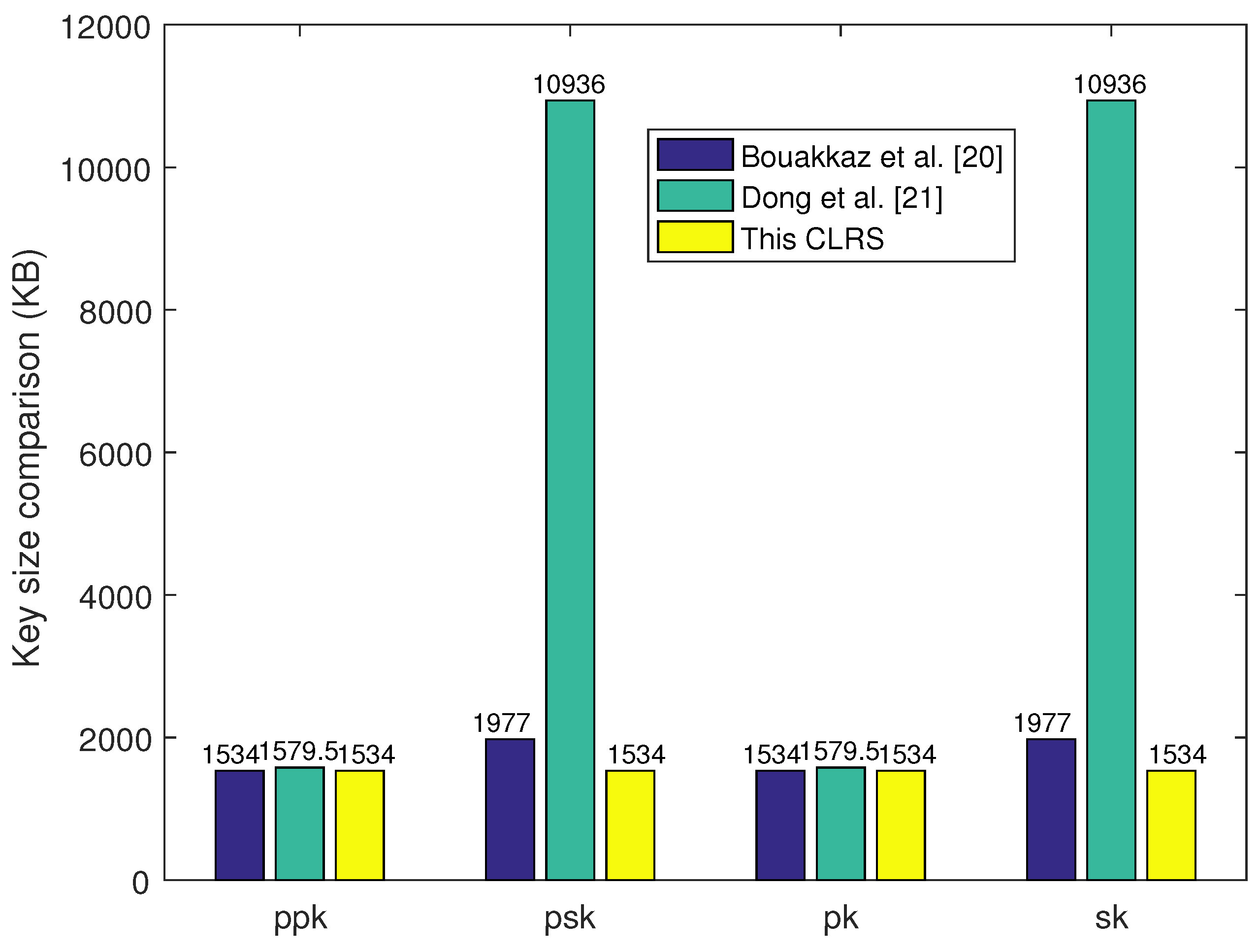

6.1. Key Size Comparison

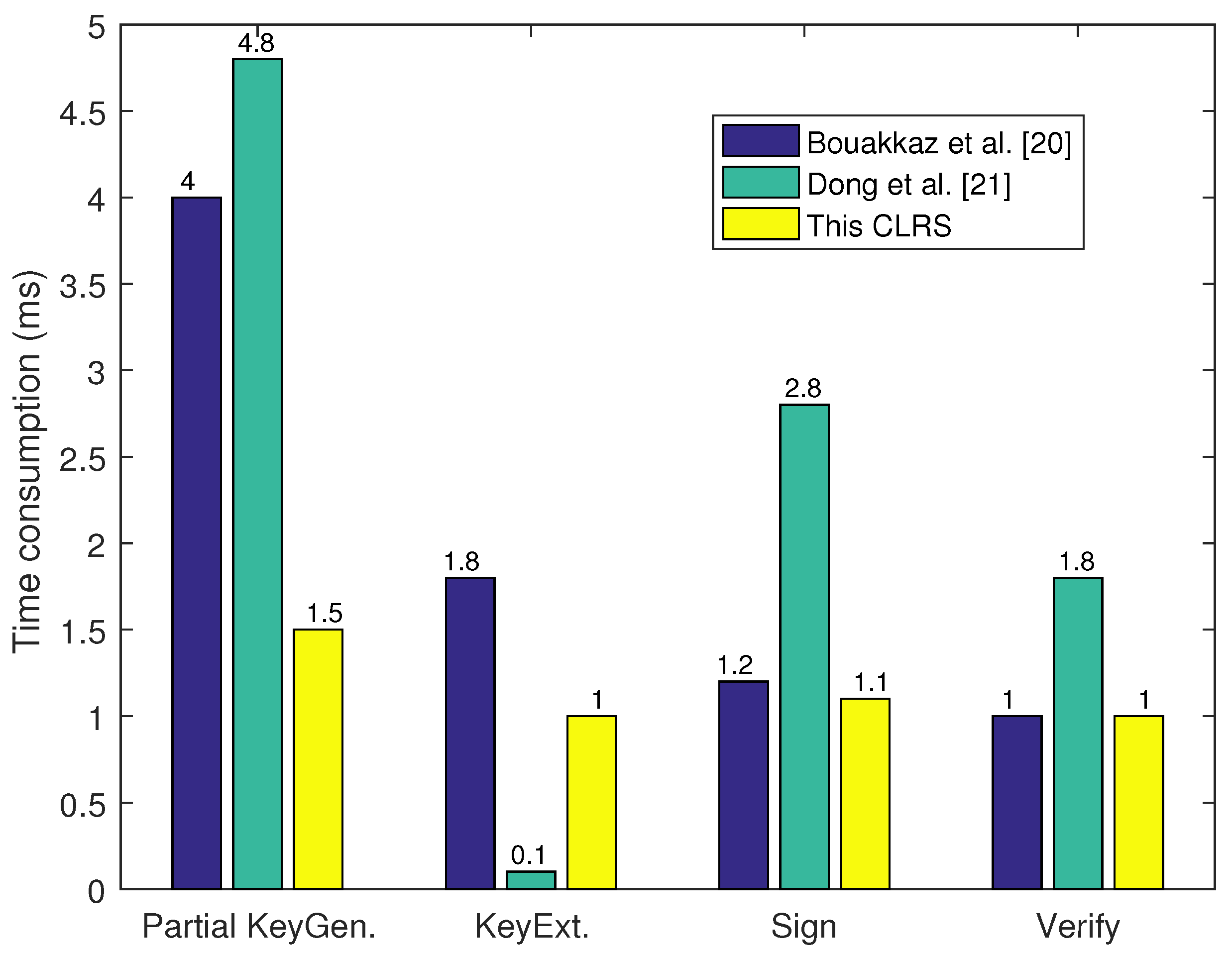

6.2. Time Consumption Comparison

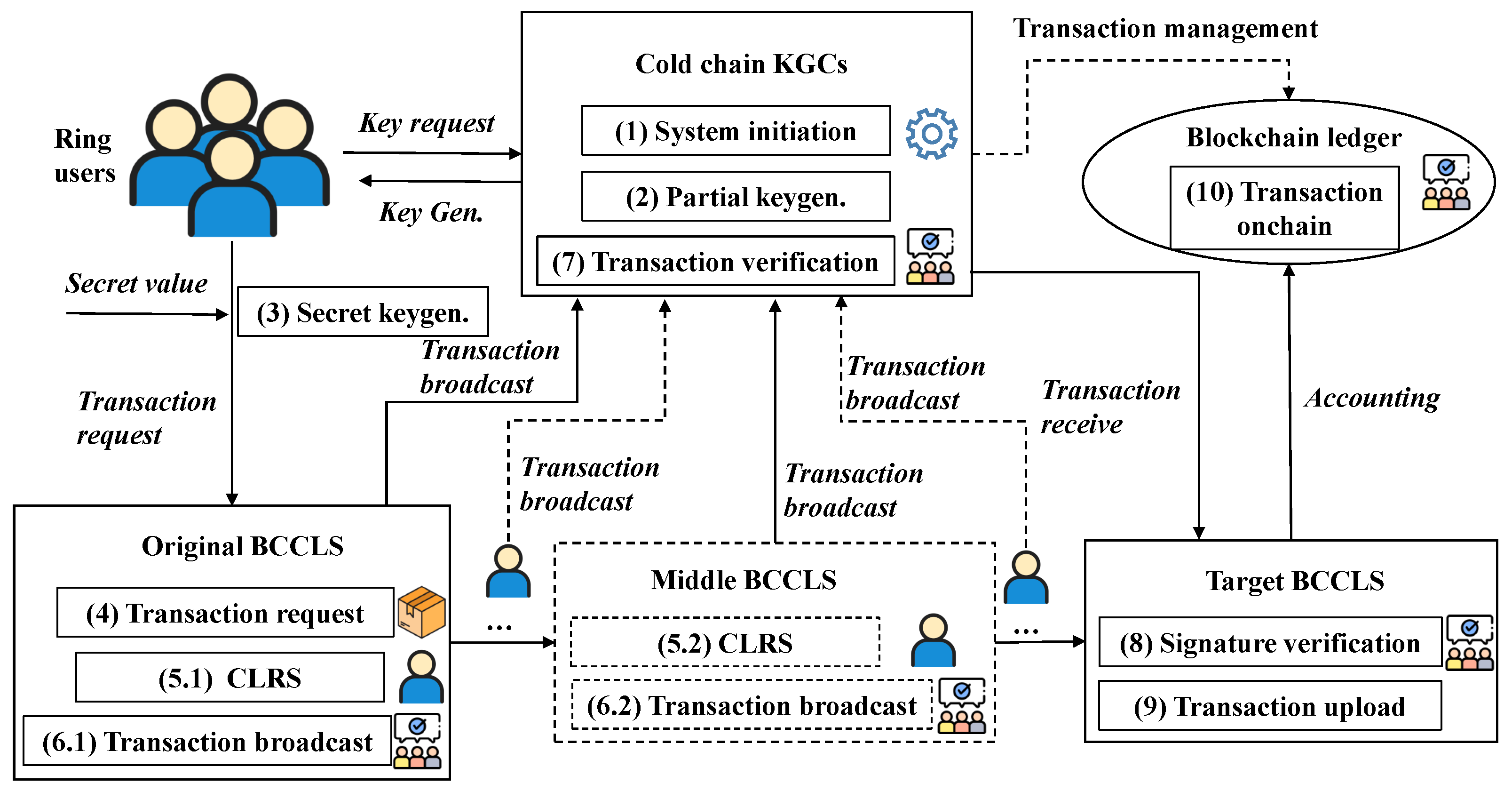

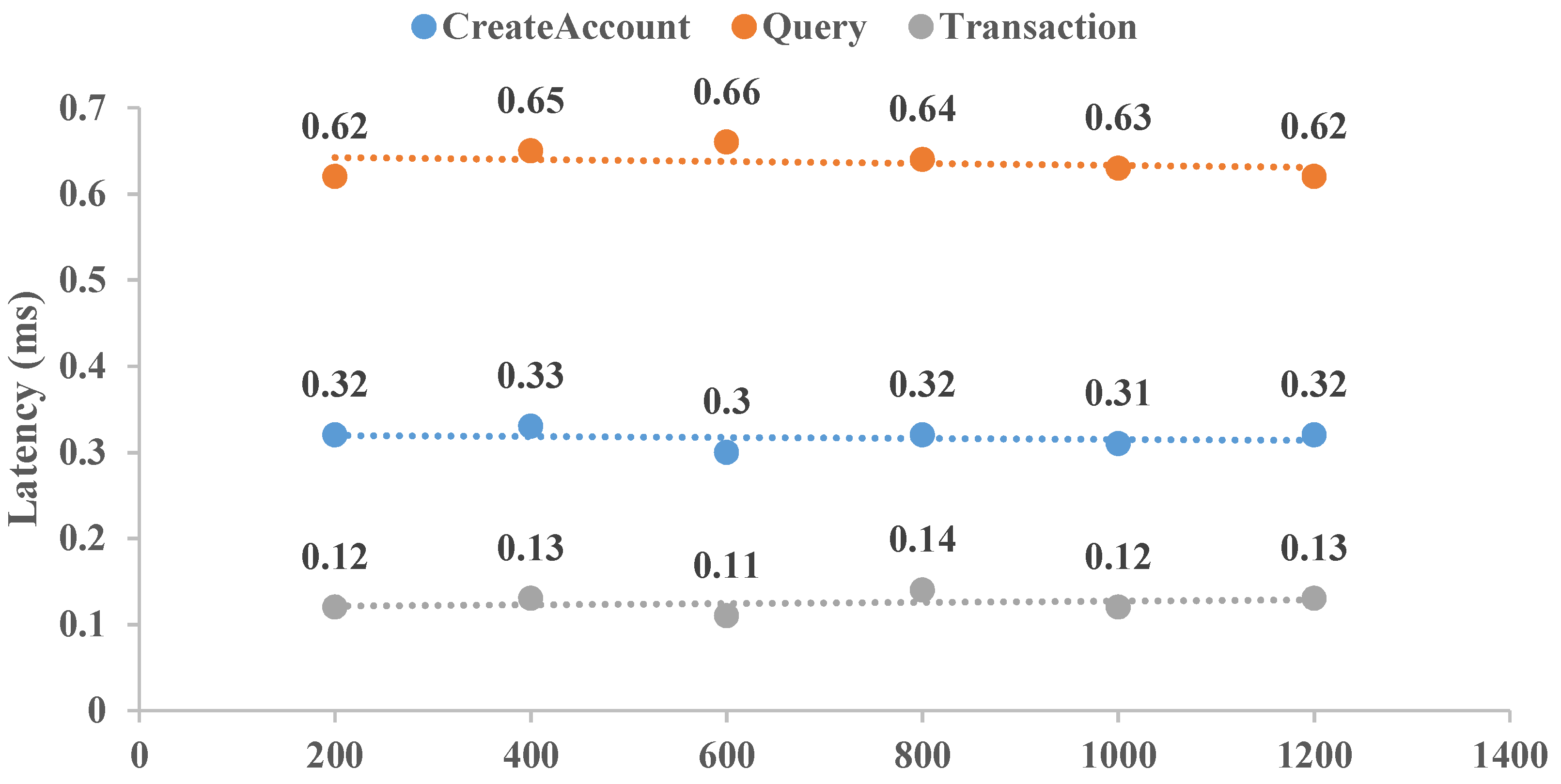

7. Example Application

- System initiation: The cold-chain KGCs in different BCCLSs compose a union and establish a distributed logistics data-sharing platform as the BCCLS network. Every KGC initiates the BCCLS and derives the system parameters . This step mainly establishes a CLRS framework and prepares for the signature algorithm.

- Partial keygen.: The KGC generates partial public and secret keys for the system user. These partial keys guarantee that users perform the signature according to the principle of the CLRS scheme. Meanwhile, they can enable the authentication of user identity as the user cannot deny the signature with these partial keys.

- Seret keygen.: The user selects a secret value and composes it with the partial keys to generate their own public and secret keys . This mechanism can resist a malicious KGC as the KGC does not grasp the full keys.

- Transaction request: Once a cold-chain good needs to be transported, the original BCCLS must initiate a blockchain transaction with the target BCCLS first. Then, all the related transaction processes are recorded in this transaction. The related operators should sign this transaction according to the signing steps of the CLRS scheme.

- CLRS: The step “5.1, 5.2, ⋯" represents the singing processes in different CCLSs. When the cold-chain goods are transported from the producing area to a supermarket, the data exchange in different parts should be recorded in the central server. Meanwhile, the related operators sign this transaction with their own keys . Note that one operator serves as the ring member in one BCCLS, which can represent the ring to sign this transaction. This ring signature mechanism can guarantee the signer’s anonymity.

- Transaction broadcast: The signed transactions should be broadcasted to the BCCLS network. This process mainly guarantees transaction validity and network-wide consistency.

- Transaction verification: The cold-chain KGC union takes responsibility for transaction verification. This process is similar to the transaction in the Bitcoin system: all the transactions should be selected, verified, and packaged. Every KGC verifies the legality of these transactions, signs with its private key, and returns the verification results back to the union manager. Only the valid transactions are packaged and served as the newest block of the blockchain ledger.

- Signature verification: When the target BCCLS receives the transaction, the signature validity is verified. With signature and message , the verifier utilizes the signer’s public key to perform this verification. Only through this verification can the transaction be accepted by the target user.

- Transaction upload: The transactions are uploaded to the BCCLS network only by passing the former verification step. The cold-chain KGC union performs this verification process and utilizes the consensus protocol to achieve network consistency.

- Transaction onchain: All the valid transactions are recorded in the unified blockchain ledger in the BCCLS network. Meanwhile, these transactions are also recorded in the corresponding BCCLS of the transaction initiator and receiver. When these transactions are recorded in the blockchain ledger, they become immutable records. This operation not only protects data and privacy but also establishes a traceability mechanism for process safety.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Keersmaeker, F.; Cao, Y.; Ndonda, G.K.; Sadre, R. A survey of public IoT datasets for network security research. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1808–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, A.; Kumar, S.A. Securing IoT Systems in a Post-Quantum Environment: Vulnerabilities, Attacks, and Possible Solutions. Internet Things 2024, 25, 101132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Namasudra, S.; Deb, S.; Ger, P.M.; Crespo, R.G. Securing IoT-based smart healthcare systems by using advanced lightweight privacy-preserving authentication scheme. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 18486–18494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shafiq, M.; Wang, L.; Srivastava, G.; Yin, S. Privacy-preserving remote sensing images recognition based on limited visual cryptography. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2023, 8, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, A.A.; Ozmen, M.O. Ultra lightweight multiple-time digital signature for the internet of things devices. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2019, 15, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Aikata, A.; Roy, S.S.; Pagliarini, S. High-speed design of post quantum cryptography with optimized hashing and multiplication. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 71, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H. Secure social internet of things based on post-quantum blockchain. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Ahmad, H. Post-quantum secure identity-based signature scheme with lattice assumption for Internet of things networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglione, A.; Esposito, J.G.; Loia, V.; Nappi, M.; Pero, C.; Polsinelli, M. Integrating Post-Quantum Cryptography and Blockchain to Secure Low-Cost IoT Devices. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 21, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, B.; Dong, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xin, X.; Ota, K. Efficient Designated Verifier Signature for Secure Cross-Chain Health Data Sharing in BIoMT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 19838–19851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; He, D.; Feng, Q.; Peng, C.; Luo, M. The implementation of polynomial multiplication for lattice-based cryptography: A survey. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2024, 83, 103782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, R.; Srivastava, G.; Gupta, G.P.; Tripathi, R.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Xiong, N.N. PPSF: A privacy-preserving and secure framework using blockchain-based machine-learning for IoT-driven smart cities. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 2326–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzafa-Alcázar, P.; Fernández-Saura, P.; Mármol-Campos, E.; González-Vidal, A.; Hernández-Ramos, J.L.; Bernal-Bernabe, J.; Skarmeta, A.F. Intrusion detection based on privacy-preserving federated learning for the industrial IoT. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 19, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Kang, X.; Liang, Y.C.; Sun, S. A trust-centric privacy-preserving blockchain for dynamic spectrum management in IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 13263–13278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Xiao, Y.; Pei, Q.; Ju, Y.; Liu, L.; Xiao, M.; Wu, C. SmartDID: A novel privacy-preserving identity based on blockchain for IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 6718–6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; D’Oliveira, R.G.; Salamatian, S.; Médard, M. Network coding-based post-quantum cryptography. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Inf. Theory 2021, 2, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Señor, J.; Portilla, J.; Mujica, G. Analysis of the NTRU post-quantum cryptographic scheme in constrained iot edge devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 18778–18790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, N.; Dong, M.; Leung, V.C.; Ritcey, J.A. Nested hash access with post quantum encryption for mission-critical iot communications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 12204–12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.S.; Deb, S.; Kalita, H.K. A novel hybrid authentication protocol utilizing lattice-based cryptography for IoT devices in fog networks. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouakkaz, S.; Semchedine, F. A certificateless ring signature scheme with batch verification for applications in VANET. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2020, 55, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yao, Y. A certificateless ring signature scheme based on lattice. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2022, 34, e7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micciancio, D.; Regev, O. Lattice-based cryptography. In Post-Quantum Cryptography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 147–191. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, C.; Peikert, C.; Vaikuntanathan, V. Trapdoors for hard lattices and new cryptographic constructions. In Proceedings of the Fortieth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, Victoria, BC, Canada, 17–20 May 2008; pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ducas, L.; Durmus, A.; Lepoint, T.; Lyubashevsky, V. Lattice signatures and bimodal Gaussians. In Annual Cryptology Conference (pp. 40–56); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bellare, M.; Neven, G. Multi-signatures in the plain public-key model and a general forking lemma. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Alexandria, VA, USA, 30 October–3 November 2006; pp. 390–399. [Google Scholar]

| Notation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| n | Security parameter |

| q | A prime number |

| m | A positive integer with |

| Error parameter | |

| L | Threshold parameter |

| Standard deviation | |

| Bimodal Gaussian distribution | |

| Cryptographic Hash function | |

| Message |

| Scheme | ppk | psk | pk | sk | sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bouakkaz et al. [20] | 1534 | 1977 | 1534 | 1977 | 1534 |

| Dong et al. [21] | 1579.5 | 10,936 | 1579.5 | 10,936 | 6770 |

| Proposed CLRS | 1534 | 1534 | 1534 | 1534 | 9.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Duan, P.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Ahmad, H. Preserving Privacy of Internet of Things Network with Certificateless Ring Signature. Sensors 2025, 25, 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051321

Zhang Y, Duan P, Li C, Zhang H, Ahmad H. Preserving Privacy of Internet of Things Network with Certificateless Ring Signature. Sensors. 2025; 25(5):1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051321

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yang, Pengxiao Duan, Chaoyang Li, Hua Zhang, and Haseeb Ahmad. 2025. "Preserving Privacy of Internet of Things Network with Certificateless Ring Signature" Sensors 25, no. 5: 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051321

APA StyleZhang, Y., Duan, P., Li, C., Zhang, H., & Ahmad, H. (2025). Preserving Privacy of Internet of Things Network with Certificateless Ring Signature. Sensors, 25(5), 1321. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051321