Sensorimotor Parameters Predict Performance on the Bead Maze Hand Function Test

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

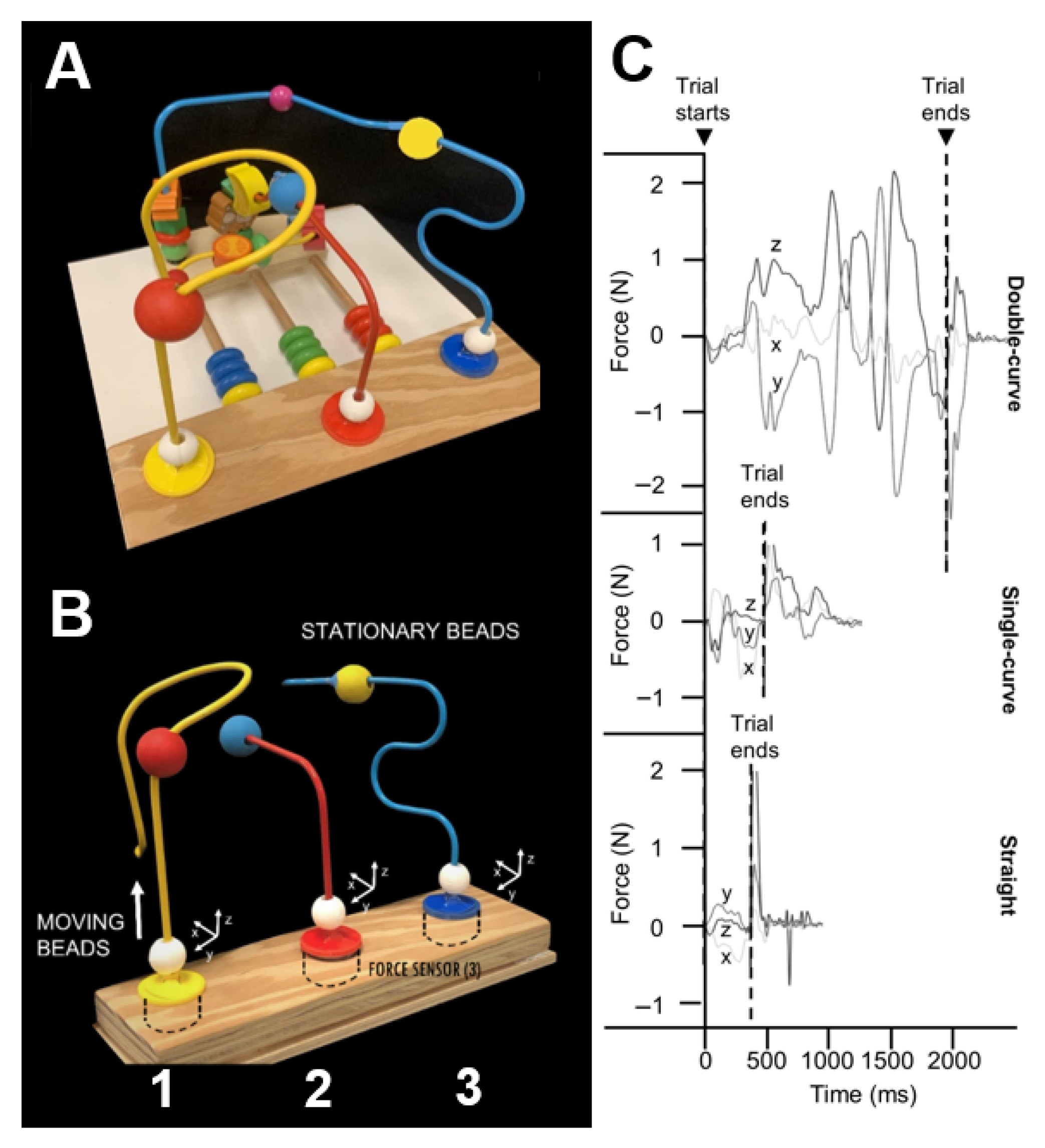

2.1. Bead Maze Hand Function Test

2.2. Laboratory-Based Dexterous Object Manipulation Task

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Total Force on the BMHF Test

2.4.2. Torque Error (TE) on the Dexterous Manipulation Task

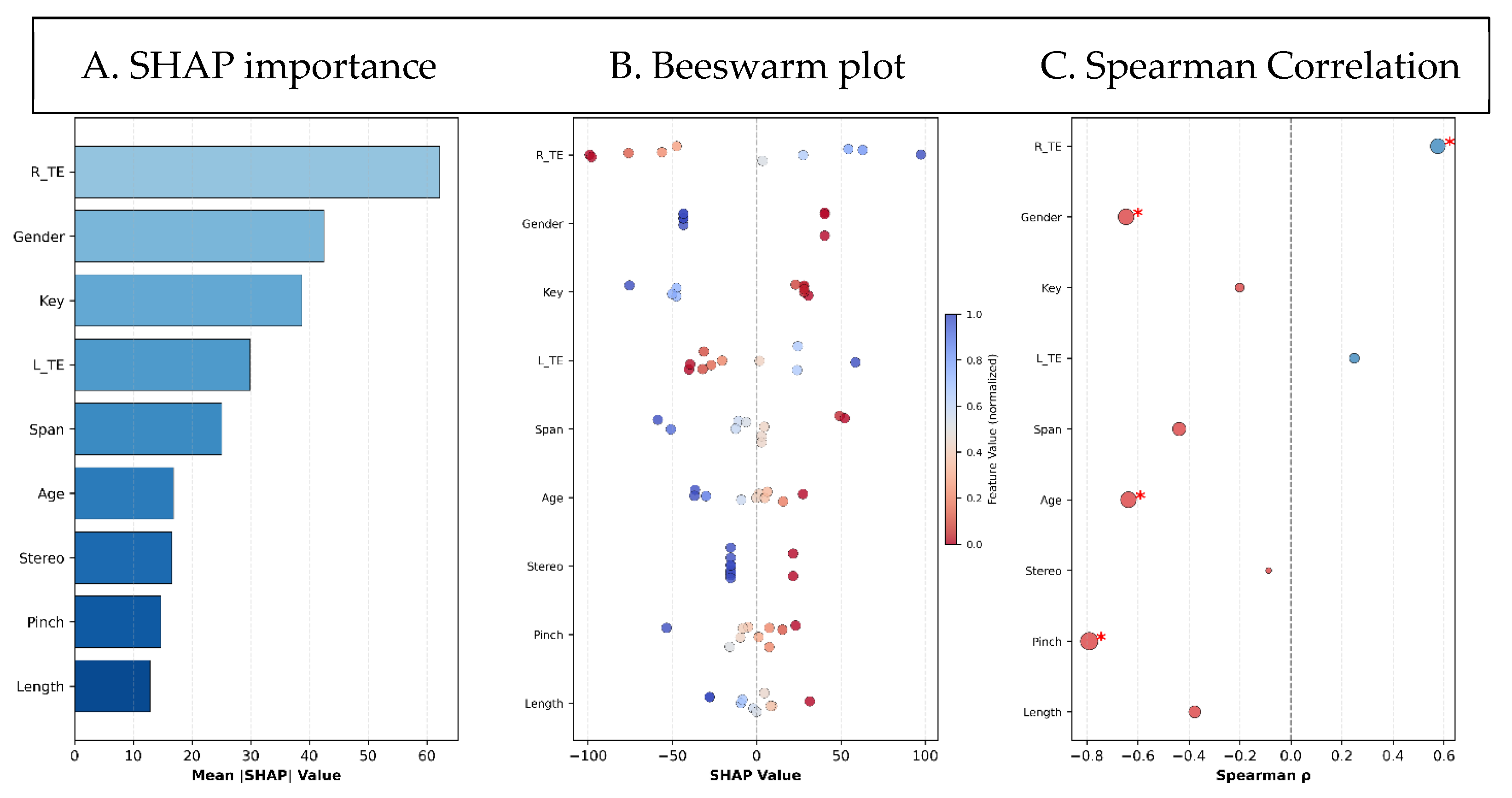

2.4.3. Statistical Analysis Using Machine Learning

3. Results

3.1. Ridge Regression Model Performance

3.2. Feature Importance

4. Discussion

4.1. Linking Lab-Based Assessments to the BMHFT

4.2. Linking Demographics and Clinical Measures to the BMHFT

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johansson, R.S.; Cole, K.J. Sensory-Motor Coordination during Grasping and Manipulative Actions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1992, 2, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.M.; Charles, J.; Steenbergen, B. Fingertip Force Planning during Grasp Is Disrupted by Impaired Sensorimotor Integration in Children with Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 60, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forssberg, H.; Eliasson, A.C.; Kinoshita, H.; Johansson, R.S.; Westling, G. Development of Human Precision Grip I: Basic Coordination of Force. Exp. Brain Res. 1991, 85, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssberg, H.; Kinoshita, H.; Eliasson, A.C.; Westling, G.; Gordon, A.M. Development of Human Precision Grip. II. Anticipatory Control of Isometric Forces Targeted for Object’s Weight. Exp. Brain Res. 1992, 90, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.M. Impaired Voluntary Movement Control and Its Rehabilitation in Cerebral Palsy. In Progress in Motor Control; Laczko, J., Latash, M.L., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 957, pp. 291–311. ISBN 978-3-319-47312-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, V.L.; Parikh, P.J. Anticipatory Control of Digit Kinematics: A Developmental Milestone for Motor Skill Acquisition. Exp. Brain Res. 2025, 243, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.M.; Westling, G.; Cole, K.J.; Johansson, R.S. Memory Representations Underlying Motor Commands Used during Manipulation of Common and Novel Objects. J. Neurophysiol. 1993, 69, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, P.J.; Fine, J.M.; Santello, M. Dexterous Object Manipulation Requires Context-Dependent Sensorimotor Cortical Interactions in Humans. Cereb. Cortex 2020, 30, 3087–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.M.; Duff, S.V. Relation between Clinical Measures and Fine Manipulative Control in Children with Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1999, 41, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, R.S.; Flanagan, J.R. Coding and Use of Tactile Signals from the Fingertips in Object Manipulation Tasks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumin, G.; Kayihan, H. Effectiveness of Two Different Sensory-Integration Programmes for Children with Spastic Diplegic Cerebral Palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2001, 23, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, D.L.; Quinlivan, J.; Owen, B.F.; Shaffrey, M.; Abel, M.F. Spasticity versus Strength in Cerebral Palsy: Relationships among Involuntary Resistance, Voluntary Torque, and Motor Function. Eur. J. Neurol. 2001, 8, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engsberg, J.R.; Ross, S.A.; Collins, D.R. Increasing Ankle Strength to Improve Gait and Function in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Pilot Study. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2006, 18, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedrizzi, E.; Pagliano, E.; Andreucci, E.; Oleari, G. Hand Function in Children with Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy: Prospective Follow-up and Functional Outcome in Adolescence. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2003, 45, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Jung, J.H.; Hahm, S.C.; Cho, H.Y. The Effects of Task-Oriented Training on Hand Dexterity and Strength in Children with Spastic Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy: A Preliminary Study. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 1800–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofani, M.; Castelli, E.; Sabbadini, M.; Berardi, A.; Murgia, M.; Servadio, A.; Galeoto, G. Examining Reliability and Validity of the Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test Among Children With Cerebral Palsy. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2020, 127, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, K.M.; Knudson, D.V. Change in Strength and Dexterity after Open Carpal Tunnel Release. Int. J. Sports Med. 2001, 22, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, E.D.; Chung, K.C. Validity and Responsiveness of the Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test. J. Hand Surg. 2010, 35, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, K.J.; Cook, K.M.; Hynes, S.M.; Darling, W.G. Slowing of Dexterous Manipulation in Old Age: Force and Kinematic Findings from the “nut-and-Rod” Task. Exp. Brain Res. 2010, 201, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, W.G.; Wolf, S.L.; Butler, A.J. Variability of Motor Potentials Evoked by Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Depends on Muscle Activation. Exp. Brain Res. 2006, 174, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gash, D.M.; Zhang, Z.; Umberger, G.; Mahood, K.; Smith, M.; Smith, C.; Gerhardt, G.A. An Automated Movement Assessment Panel for Upper Limb Motor Functions in Rhesus Monkeys and Humans. J. Neurosci. Methods 1999, 89, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, P.J.; Cole, K.J. Handling Objects in Old Age: Forces and Moments Acting on the Object. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, V.L.; Ajoy, A.; Johnston, C.A.; Gogola, G.R.; Parikh, P.J. The Bead Maze Hand Function Test for Children. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2024, 78, 7804205010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sakzewski, L.; Ziviani, J.; Boyd, R. The Relationship between Unimanual Capacity and Bimanual Performance in Children with Congenital Hemiplegia. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Mehta, N.; Patel, P.; Parikh, P.J. Effects of Aging on Conditional Visuomotor Learning for Grasping and Lifting Eccentrically Weighted Objects. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 131, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.M. Development of Hand Motor Control. In Handbook of Brain and Behaviour in Human Development; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 513–537. ISBN 0-7923-6943-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Bohannon, R.W.; Kapellusch, J.; Garg, A.; Gershon, R.C. Dexterity as Measured with the 9-Hole Peg Test (9-HPT) across the Age Span. J. Hand Ther. 2015, 28, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cule, E.; De Iorio, M. Ridge Regression in Prediction Problems: Automatic Choice of the Ridge Parameter. Genet. Epidemiol. 2013, 37, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogutu, J.O.; Schulz-Streeck, T.; Piepho, H.-P. Genomic Selection Using Regularized Linear Regression Models: Ridge Regression, Lasso, Elastic Net and Their Extensions. BMC Proc. 2012, 6, S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, P. Machine Learning in Action; Manning Publications Co. LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-61729-018-3. [Google Scholar]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; Springer Texts in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-07-161417-4. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, R.; Nakagome, S.; Paloski, W.H.; Contreras-Vidal, J.L.; Parikh, P.J. Assessment of Biomechanical Predictors of Occurrence of Low-Amplitude N1 Potentials Evoked by Naturally Occurring Postural Instabilities. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, K.M.; Newell, K.M. Changes in the Structure of Children’s Isometric Force Variability with Practice. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2004, 88, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits-Engelsman, B.; Coetzee, D.; Valtr, L.; Verbecque, E. Do Girls Have an Advantage Compared to Boys When Their Motor Skills Are Tested Using the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd Edition? Children 2023, 10, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flatters, I.; Hill, L.J.B.; Williams, J.H.G.; Barber, S.E.; Mon-Williams, M. Manual Control Age and Sex Differences in 4 to 11 Year Old Children. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decraene, L.; Feys, H.; Klingels, K.; Basu, A.; Ortibus, E.; Simon-Martinez, C.; Mailleux, L. Tyneside Pegboard Test for Unimanual and Bimanual Dexterity in Unilateral Cerebral Palsy: Association with Sensorimotor Impairment. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M.H.; Santello, M. Hand Function: Peripheral and Central Constraints on Performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 96, 2293–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits-Engelsman, B.C.M.; Westenberg, Y.; Duysens, J. Development of Isometric Force and Force Control in Children. Cogn. Brain Res. 2003, 17, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.M.; Spedden, M.E.; Dietz, M.J.; Karabanov, A.N.; Christensen, M.S.; Lundbye-Jensen, J. Cortical Signatures of Precision Grip Force Control in Children, Adolescents, and Adults. eLife 2021, 10, e61018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.K.; Oliveira, M.A.; Hsu, J.; Huang, J.; Park, J.; Clark, J.E. Hand Digit Control in Children: Age-Related Changes in Hand Digit Force Interactions during Maximum Flexion and Extension Force Production Tasks. Exp. Brain Res. 2007, 176, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayanidhi, S.; Hedberg, Å.; Valero-Cuevas, F.J.; Forssberg, H. Developmental Improvements in Dynamic Control of Fingertip Forces Last throughout Childhood and into Adolescence. J. Neurophysiol. 2013, 110, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Vidal, J.L.; Bo, J.; Boudreau, J.P.; Clark, J.E. Development of Visuomotor Representations for Hand Movement in Young Children. Exp. Brain Res. 2005, 162, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.M.; Charles, J.; Duff, S.V. Fingertip Forces during Object Manipulation in Children with Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy. II: Bilateral Coordination. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1999, 41, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleim, J.A.; Jones, T.A. Principles of Experience-Dependent Neural Plasticity: Implications for Rehabilitation After Brain Damage. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2008, 51, S225–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matusz, P.J.; Key, A.P.; Gogliotti, S.; Pearson, J.; Auld, M.L.; Murray, M.M.; Maitre, N.L. Somatosensory Plasticity in Pediatric Cerebral Palsy Following Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy. Neural Plast. 2018, 2018, 1891978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvinpour, S.; Shafizadeh, M.; Balali, M.; Abbasi, A.; Wheat, J.; Davids, K. Effects of Developmental Task Constraints on Kinematic Synergies during Catching in Children with Developmental Delays. J. Mot. Behav. 2020, 52, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.K.; Prigge, P.P. Early Upper-Limb Prosthetic Fitting and Brain Development: Considerations for Success. J. Prosthet. Orthot. 2020, 32, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rose, V.L.; Kukkar, K.K.; Chen, T.A.; Parikh, P.J. Sensorimotor Parameters Predict Performance on the Bead Maze Hand Function Test. Sensors 2025, 25, 7670. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247670

Rose VL, Kukkar KK, Chen TA, Parikh PJ. Sensorimotor Parameters Predict Performance on the Bead Maze Hand Function Test. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7670. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247670

Chicago/Turabian StyleRose, Vivian L., Komal K. Kukkar, Tzuan A. Chen, and Pranav J. Parikh. 2025. "Sensorimotor Parameters Predict Performance on the Bead Maze Hand Function Test" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7670. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247670

APA StyleRose, V. L., Kukkar, K. K., Chen, T. A., & Parikh, P. J. (2025). Sensorimotor Parameters Predict Performance on the Bead Maze Hand Function Test. Sensors, 25(24), 7670. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247670