1. Introduction

Forward-scatter radar (FSR) is a specialised bistatic radar configuration in which the transmitter (TX) and receiver (RX) are positioned such that the bistatic angle approaches 180°. When a target crosses the baseline between them, it disrupts the direct signal path, resulting in a distinctive amplitude variation in the received signal due to the shadowing effect. This effect is particularly prominent when the target is near the baseline, where the forward-scattered pattern causes enhanced power while demonstrating stability in both amplitude and phase. Consequently, the resulting amplitude modulation is only governed by the target instantaneous phase, enabling the detection of the target and estimation of its instantaneous bistatic Doppler along the trajectory. Although FSR systems are inherently limited in range and velocity resolution, they offer several practical advantages. These include effective detection of low radar cross-section (RCS) targets, robustness to stealth technology, and a simplified system architecture that facilitates low-cost solutions [

1,

2].

Additionally, FSR systems are well-suited to passive radar implementations, where the use of existing transmitters eliminates the need for an active source, thereby reducing system complexity due to enabling the deployment of a passive receiver alone. Further, it enables covert operation of the radar. This approach has been extensively explored using transmitters of opportunity, including Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) [

3], Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) [

4], Long-Term Evolution (LTE) [

5], radio and television broadcast signals [

6,

7], and Wi-Fi systems [

8]. In this paper, we specifically focus on orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) waveforms, which are ubiquitous across modern communication systems from Wi-Fi and cellular networks to digital television and radio broadcasting. This choice is particularly relevant in the context of Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC) [

9,

10], a rapidly emerging paradigm that envisions the convergence of radar sensing and wireless communications within a unified framework.

In conventional FSR systems, where a single antenna is employed, target detection is typically performed in the bistatic Doppler domain using time-domain processing, which analyses the amplitude modulation induced by targets as they move across the baseline [

1,

2,

6,

7].

Alternatively, a limited number of studies have investigated space-domain processing using a multi-channel FSR (MC-FSR), where detection is performed in the angular domain by analysing the amplitude modulation across spatially distributed antenna elements [

11,

12]. As the modulation rate varies with the target’s position, this approach enables effective estimation of the direction of arrival (DoA). In contrast to conventional array processing techniques, the proposed non-coherent approach avoids the need for phase synchronisation among antenna elements, while demonstrating robustness against phase noise. Furthermore, thanks to its implementation on individual time snapshots, it supports different waveform types and facilitates the suppression of direct-path signals across spatial samples by spatial filtering [

12].

Due to the relatively small number of array elements compared to the abundance of time-domain samples, space-domain processing in MC-FSR faces inherent challenges in detecting weak targets and achieving fine angular resolution. These limitations become particularly critical in multi-target scenarios, where accurate angular discrimination is essential. The problem is further exacerbated by the aim of preserving low system complexity and cost, which typically restricts the number of antenna elements that can be deployed.

To address these challenges while maintaining system simplicity, in this paper we have explored the application of Multiple Signal Classification (MUSIC) algorithm, as a super-resolution technique, to the MC-FSR system. This study builds on the preliminary results presented in [

13,

14]. In particular, the MUSIC algorithm is adapted to operate directly on amplitude-only (real-valued) data and a comprehensive framework for the MUSIC-based MC-FSR using arbitrary waveforms is developed. Then, focusing on OFDM waveforms, we study their specific impact on target detection and DoA estimation performance of the proposed MUSIC-based approach. We address corresponding advantages and limitations and propose solutions based on sub-band approach and spatial smoothing.

In particular, the benefits of spatial smoothing are theoretically investigated, along with applicable trade-offs in terms of computational complexity and reduction in the available DoFs. Exploiting the sub-band approach proposed in [

6], we can address the decay of moving target signatures resulting from the autocorrelation properties of OFDM signals, though it introduces a trade-off by reducing the MUSIC response of stationary (or slowly moving) targets. The sub-band technique and the spatial smoothing can be combined, as needed, to make the system robust across a range of target dynamics.

The benefits and limitations of the MUSIC-based MC-FSR approach are explored through detailed discussion and simulation, offering practical insights into its deployment. The proposed approach shows significant improvement in angular resolution, enabling reliable discrimination of closely spaced targets, despite using a limited number of channels on receipt.

In addition, a series of dedicated experimental tests using OFDM signals are conducted to assess real-world feasibility. For this purpose, an S-band multi-channel FSR system was implemented using software-defined radios (SDRs) and commercial Wi-Fi antennas. The experimental setups include scenarios involving cooperative targets such as people and drones moving across different trajectories. The results confirm the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed approach under realistic operating conditions.

The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 summarizes the MC-FSR signal model and the space-domain processing principle. The MUSIC-based MC-FSR processing scheme is introduced in

Section 3. A theoretical analysis of the effect of OFDM waveform is given in

Section 4.

Section 5 presents the simulation results.

Section 6 describes the experimental setup and reports corresponding results to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach under real-world conditions. Finally, conclusions are drawn in

Section 7.

2. MC-FSR Signal Model and Space-Domain Processing Principle

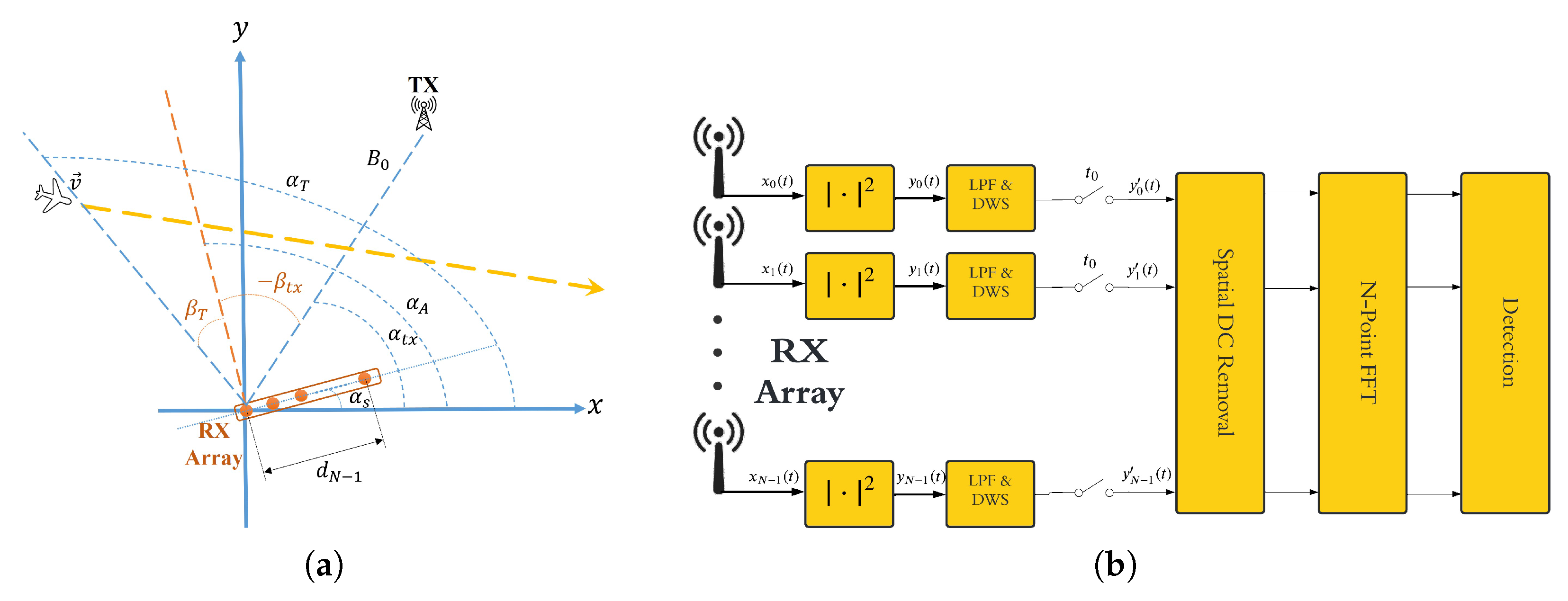

Figure 1 shows the geometry and the signal processing block-diagram of an MC-FSR system. The receiver (RX) consists of a linear array of

N identical antennas, with the first element, designated as the reference, positioned at the origin of a Cartesian coordinate system. The distance between the

n-th element and the origin is denoted by

, where

, and

. The entire RX array is oriented at an angle

counterclockwise from the positive x-axis, resulting in a broadside angle of

. The transmitter (TX) is placed at a distance

from the origin and forms an angle

with respect to the positive x-axis. The TX transmits a waveform denoted by

in the baseband.

In the absence of a target, the received signals at the RX array are exclusively due to the direct path from the transmitter, along with additive receiver noise. Assuming standard far-field and narrow-band conditions, the signal received at the

n-th antenna can be modeled as

where the coefficient

encapsulates the free-space path loss and phase delay between the transmitter and the reference RX element (i.e.,

). The phase shift at the

n-th receiver due to array geometry is given by

with

. The noise component

represents additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN), modeled as a zero-mean circularly symmetric complex Gaussian variable.

As in conventional single-channel FSR systems [

2,

6,

15,

16], the squared amplitude of the received signals are exploited in the proposed MC-FSR system:

where

denotes the real part. It is straightforward to observe that, aside from the noise terms, the received signal maintains a constant amplitude across all array elements at a given time. Consequently, when the direct signal-to-noise ratio (DNR) is sufficiently high, a nearly uniform amplitude profile is obtained across the array, independent of the transmitted waveform.

Now, let us consider the case where a target crosses the baseline, forming an angle

with respect to the positive x-axis. Under this condition, the received signal at the

n-th element becomes

The second term in (

4) represents the signal scattered by the target in the forward direction. There, the time-varying complex amplitude

models the overall TX-target-RX path loss as well as the target’s forward-scattering characteristics (see [

2] for the detailed formulations). Further,

is the (bistatic) delay of target-scattered signal in which

and

represent the target distance from the transmitter and the reference receiver, respectively; it quantifies the excess path length relative to the direct signal. The corresponding instantaneous phase at the

n-th array element is given by

where

denotes the angle of arrival of the target signal relative to the array broadside.

The expression for the squared signal amplitude in target presence becomes

Under typical conditions of high DNR and

, we get

where

represents the observation noise in the signal model and is a real-valued Gaussian random process. Substituting from (

2) and (

6), we further simplify the signal model in (

8) as

where

,

, and

. Even if we assume a constant-amplitude waveform, it is clear that the second term in (

9) introduces amplitude modulation which is a sole effect of the presence of the target. The temporal amplitude variation, which is governed by the instantaneous phase term

, is the primary feature exploited by time-domain processing in conventional single-channel FSR for target detection in the bistatic Doppler domain. However, according to the formula, amplitude also varies spatially across array elements (i.e., with

n), which is the key point in the principle of operation of a MC-FCR [

11,

12]. Specifically, the rate of spatial amplitude modulation, with respect to the antenna index

n, is governed by the DoA parameter

. In order to exploit this effect, the signal processing scheme in

Figure 1b can be adopted. Specifically, a spatial DC removal is first performed by subtracting the DC component of the signal estimated across the rx channels at each time snapshot. For sufficiently large

N, this stage is expected to cancel out the first term in (

8) as it does not depend on spatial index

n. Therefore, for a specific time snapshot at

, we obtain

Consequently, conducting a spatial frequency analysis on individual signal snapshots holds the potential to detect the presence of a target and subsequently estimate its DoA. In the block diagram shown in

Figure 1b, this spatial frequency analysis is performed using a fast Fourier transform (FFT), under the assumption that a uniform linear array (ULA) is employed. The resulting FFT output is then used to perform threshold-based detection in the DoA domain.

It is worth mentioning that although this space-domain processing for MC-FSR may appear similar to conventional phased-array techniques, it fundamentally differs in that target detection and localization are performed using an amplitude-based, inherently non-coherent approach. As a result, owing to its distinct characteristics compared to traditional phased array processing—such as much simpler array calibration—it achieves a notable reduction in system complexity, albeit with some inherent limitations, including sign ambiguity [

12].

Whilst the FFT-based space-domain processing described above provides a straightforward solution for MC-FSR, it suffers from notable limitations. In particular, unlike the FFT-based time-domain FSR processing, which benefits from a large number of available time samples, the detection performance and the angular resolution are inherently constrained by the number of array elements, making it difficult to distinguish closely spaced or weak targets. Taking into account the primary purpose of having a low-cost system, this becomes especially problematic in multi-target scenarios under strict hardware constraints where only a limited number of antennas are deployed. In the next section, we seek application and adaptation of the MUSIC algorithm, as a super-resolution technique, to address this important challenge.

3. MUSIC-Based MC-FSR Processing Framework

To overcome the limitations in angular resolution and ambiguity handling associated with FFT-based space-domain processing, this section introduces the application of the MUSIC algorithm to the MC-FSR framework. MUSIC is a well-established super-resolution technique for DoA estimation in phased array systems. It exploits the eigenspace structure of the covariance matrix to distinguish between signal and noise subspaces, thereby achieving superior angular discrimination. However, its direct application to MC-FSR requires specific adaptations. In particular, since MC-FSR operates on amplitude-only, real-valued signal snapshots, the conventional complex-valued steering vectors must be reformulated, and the number of DoFs appropriately adjusted. These modifications are essential for maintaining accurate subspace separation and ensuring the algorithm’s effectiveness under real-valued conditions.

We let the RX array to be a ULA (

). Then, considering a multi-target scenario with

k targets, the received signal model in (

9) (before DC removal) can be rewritten as:

where

,

, and

are defined as in (

9) for the

k-th target (

). The matrix form of the received signal is given by:

where

is the received signal vector, and

is the noise vector, which is a zero-mean white Gaussian vector with covariance matrix

. The amplitude

is a

vector, defined as:

and the

matrix

is given by:

where each steering matrix

is defined as:

Here,

is the steering matrix at direction

u, and

corresponds to the direct-path signal.

It is important to emphasize that the classical MUSIC algorithm—formulated for complex-valued, phase-coherent array measurements—cannot be directly applied to the MC-FSR system. In MC-FSR, the receiver operates on real-valued amplitude-only snapshots obtained after squaring the received signal magnitude. As a result, the standard complex steering vectors used in coherent array processing do not represent the physical measurement model of amplitude-based MC-FSR. Furthermore, the direct-path signal always contributes an additional deterministic component that must be explicitly treated as a separate source. For these reasons, the conventional MUSIC formulation would lead to an incorrect signal subspace structure, an incorrect dimensionality of the subspace, and ultimately an inconsistent DoA estimate. These fundamental differences necessitate a dedicated adaptation of the MUSIC algorithm to operate correctly in amplitude-only, non-coherent MC-FSR settings.

To extract the signal and noise subspaces, an eigenvalue decomposition of the sample covariance matrix

is performed:

The signal subspace, denoted by

, comprises the eigenvectors associated with the

p largest eigenvalues of

, corresponding to the dominant signal components. The noise subspace, given by

, consists of the remaining

eigenvectors associated with the smaller eigenvalues. In the context of MC-FSR with

K signal sources, the signal subspace must include

eigenvectors. This accounts for

K real-valued target signals and the contribution from the direct-path signal.

The peaks in the MUSIC spatial spectrum, evaluated over a specified range of

u, correspond to the DoA of the targets. Using the estimated noise subspace

and the steering matrix

, the MUSIC spatial spectrum is computed as:

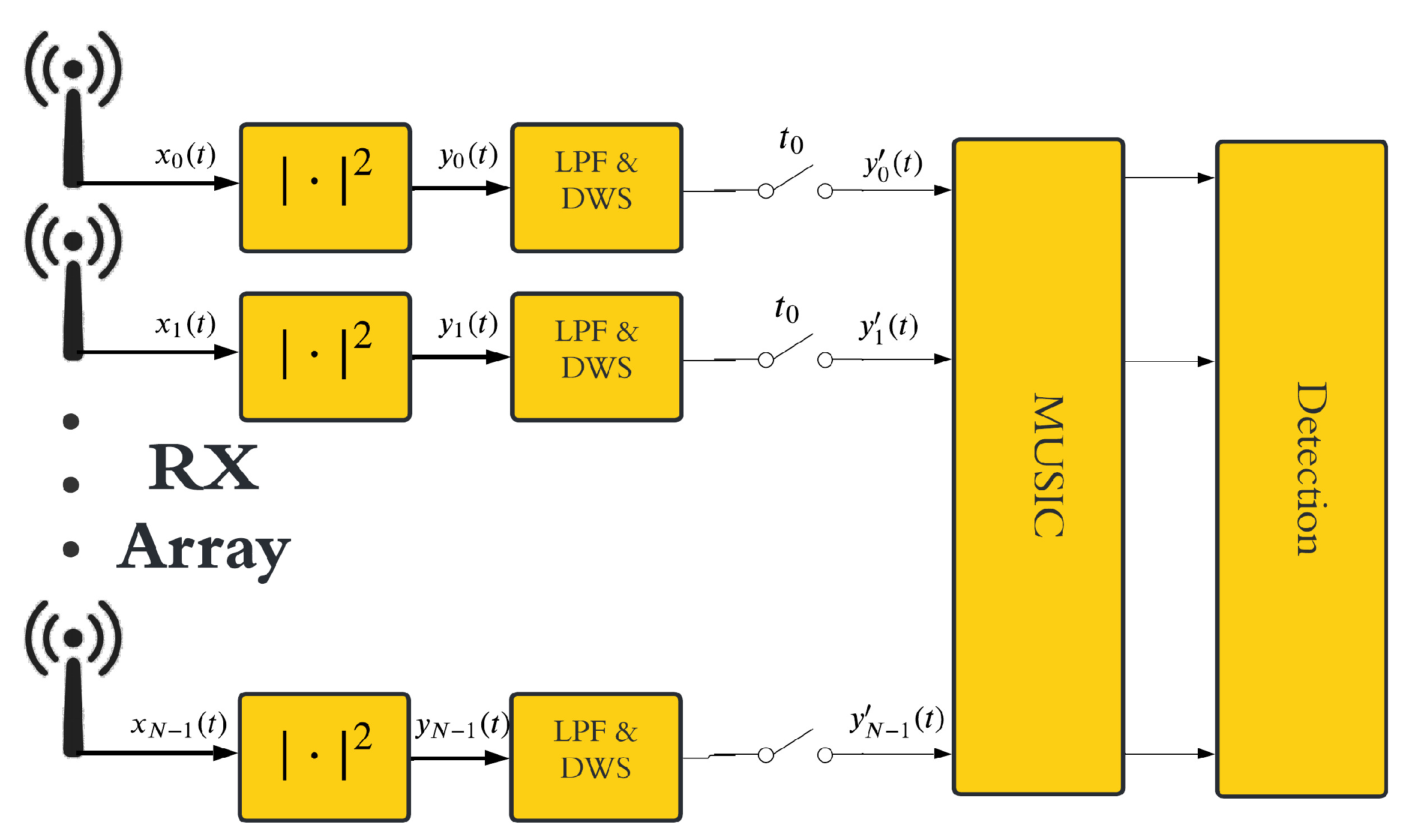

Since the MUSIC algorithm allows discriminating all present sources, including the direct-path signal from the transmitter, a dedicated DC removal stage becomes unnecessary. As a result, the overall signal processing scheme is streamlined as in

Figure 2.

A main challenge associated with MUSIC algorithm is the processing of the correlated signals which is typical in radar scenarios. In this regard, spatial smoothing is a well-established technique for decorrelating signals. This is achieved by partitioning the full array into L overlapping subarrays, each consisting of elements, where and , with p denoting the number of DoFs. The smoothed covariance matrix is obtained by averaging the covariance matrices computed for each subarray . This matrix is then used in place of the original covariance matrix within the MUSIC algorithm to mitigate the degrading effects of source correlation.

The effectiveness of spatial smoothing strongly depends on the choice of the number of subarrays. When the number of antennas is limited, this choice is highly constrained, as it may leads to the lack of required DoFs, degrading the system performance. In addition, spatial smoothing introduces extra computational complexity, which may be unjustified in cases where signal correlation is not critical.

4. Effect of OFDM Waveforms and Sub-Band Processing

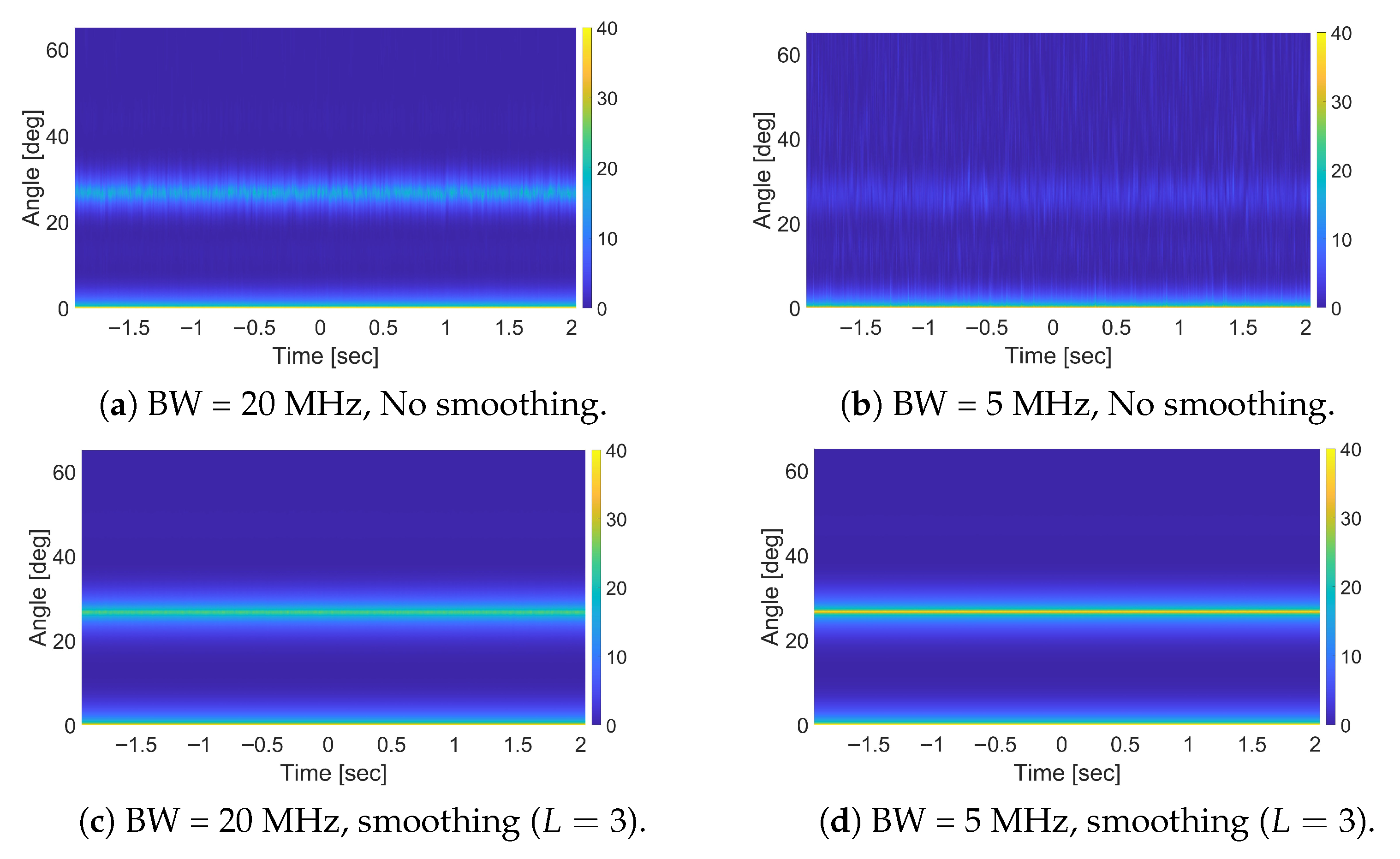

Applying the MUSIC algorithm to MC-FSR using different waveforms can lead to different results, as the output is inherently influenced by the specific characteristics of the adopted signals, especially in terms of signal autocorrelation. In this context, incorporating spatial smoothing may offer certain advantages, but it can also introduce potential drawbacks. In the following, we specifically investigate the impact of using an OFDM waveform to enable efficient and targeted use of spatial smoothing. This ensures improved system performance while maintaining computational efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

To this purpose, we focus on a single-target scenario and rewrite the noiseless received signal model in (

11) as:

where

, and

denote the direct and target-path signal components, respectively. For simplicity, the subscript indices in

,

, and

are omitted.

We assume that the transmitted signal

is a wide-sense stationary (WSS) random process, independent of

. Our analysis focuses on the statistical properties of the received signals over short time intervals, which are typically used for covariance matrix estimation. Within such intervals,

and

are treated as time-invariant, so that we omit the time dependence. In contrast,

, which varies more rapidly, remains time-dependent. The correlation between the direct-path signal

and the target-path signal

can thus be expressed as:

where we have used

. As is apparent, the correlation between the two signal sources depends both on the waveform characteristics, via the second factor in the r.h.s. of (

18), and on the motion of the target through the last factor in the r.h.s. of (

18). For an OFDM signal with a sufficiently large number of subcarriers, the central limit theorem (CLT) enables us to approximate

as a complex Gaussian process. As a result,

,

, and

can all be regarded as circularly symmetric complex Gaussian random variables. Under these conditions, by expanding the expectation term in (

18), we have

Since for a circularly symmetric complex Gaussian variable

X, we have

, the second term vanishes. Consequently, (

18) reduces to

where

is the signal power and

denotes the autocorrelation function of

.

For a moving target, the time-varying phase , caused by the Doppler effect, significantly reduces the correlation between the target-path signal and the direct-path signal , irrespective of the signal auto-correlation . In particular, if the target’s velocity is sufficiently high, the resulting Doppler shift introduces rapid phase variations, effectively decorrelating the signals across snapshots. In the limiting case, can be modeled as a white random process uniformly distributed over . Consequently, , implying that and become completely uncorrelated. Under such conditions, spatial smoothing is no longer necessary.

However, when the target is stationary, the phase term is time-invariant (i.e., zero Doppler), so is constant. Consequently, is also a constant, which can be absorbed into . This means, even for a stationary target or one with a small bistatic Doppler shift, the correlation between and decreases since it directly reflects the correlation properties of the originals signal .

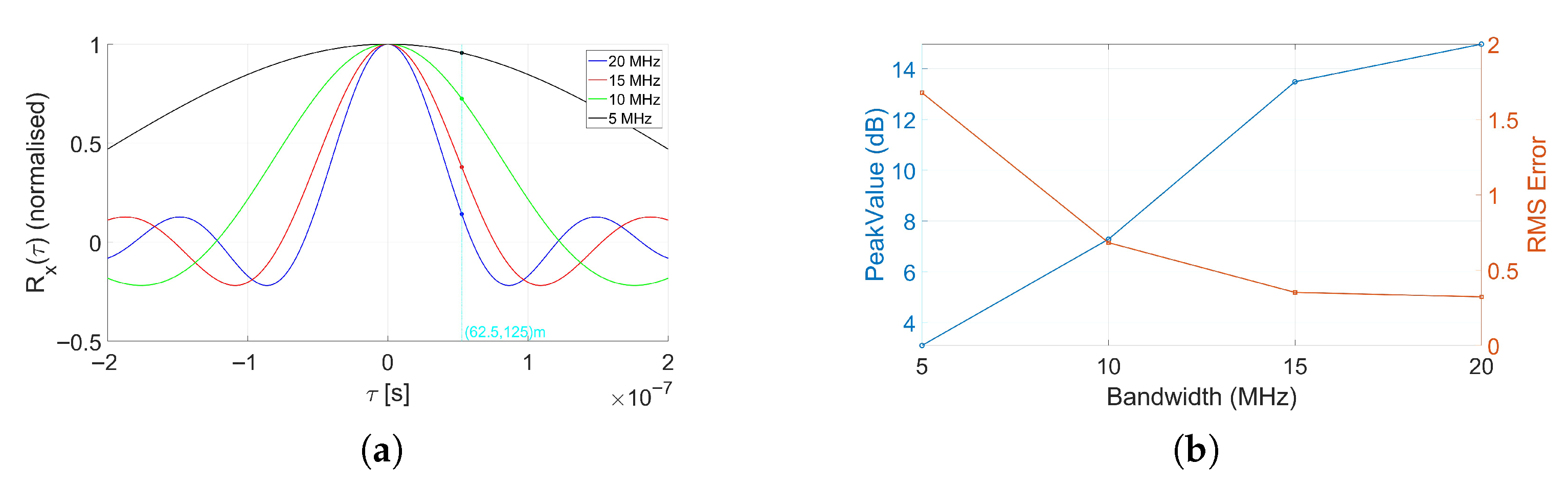

The autocorrelation function of an OFDM signal can be expressed by

, which is inversely proportional to the waveform bandwidth

B and the delay

. As the bistatic delay increases, the correlation diminishes, which is advantageous for MUSIC-based processing. On the other hand, this reduction in correlation adversely affects the fundamental FSR principle, as it decreases the average power of the target-path signal

[

6]. In particular, it has been shown that the expected output target signature in space-domain processing is proportional to

[

12]. Consequently, due to the large bandwidth and corresponding sinc-shaped

of OFDM waveforms, target response becomes susceptible to rapid fading, especially for moving targets with larger bistatic delays. This behaviour limits the performance of the MC-FSR using OFDM waveforms as compared to the narrowband waveforms.

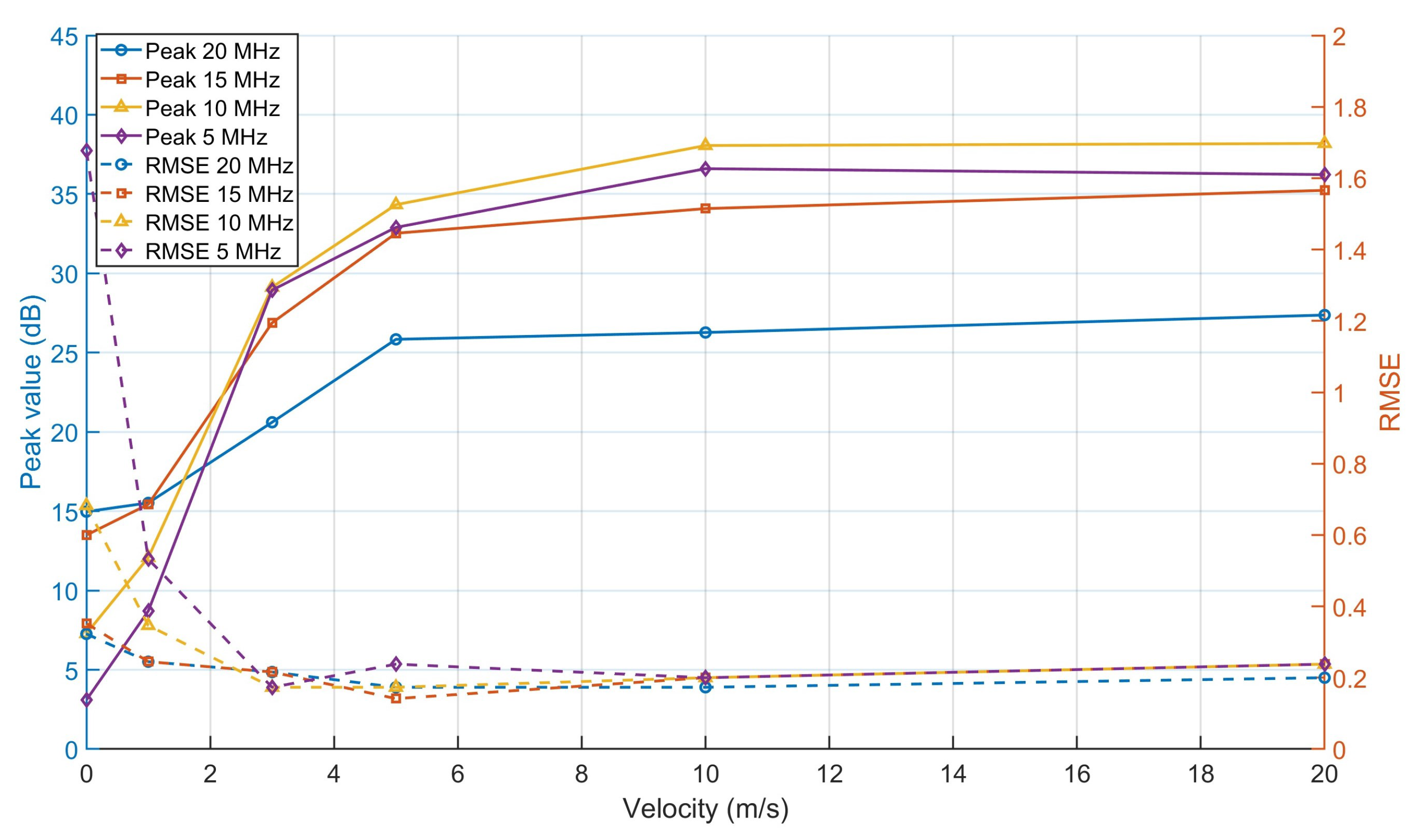

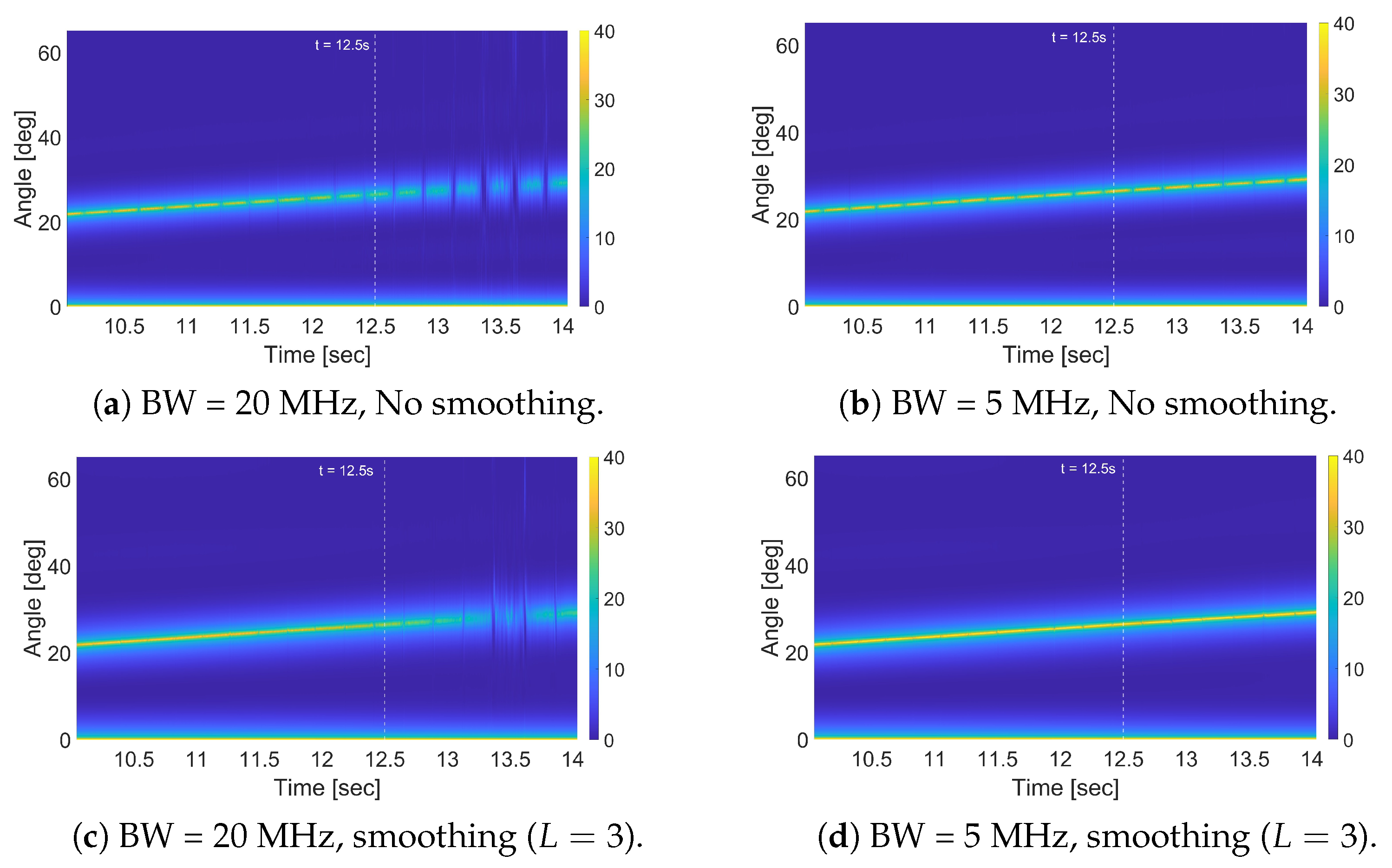

To counteract this effect, sub-band processing can be applied to reduce the effective bandwidth via pre-filtering, thereby slowing the decay of the autocorrelation function [

6], while this approach improves the persistence of off-baseline target signatures, it also increases the correlation between the direct-path and target-path signals. This, in turn, may hinder the detection of stationary targets. To address this trade-off, spatial smoothing can be introduced to mitigate the increased correlation, thus enhancing the separability of stationary targets while retaining improved visibility for moving ones. Together, sub-band processing and spatial smoothing provide a complementary strategy for balancing detection performance in mixed-target scenarios, as both are governed by the autocorrelation characteristics of the waveform.

6. Experimental Tests

To validate the performance of the proposed MUSIC-based MC-FSR framework using OFDM signals, an experimental campaign was carried out using the parameters reported in

Table 6. The acquisition setup is illustrated in

Figure 11. On the transmitter side, an Ettus USRP-B210 (Ettus Research, Austin, TX, USA) was used to generate either an OFDM signal at a carrier frequency of

GHz and a bandwidth of

MHz, controlled via MATLAB R2024b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) The signal was split using an RF splitter: one branch fed the transmitting antenna, while the other was routed to the receiver circuitry for monitoring transmission activity. As the processing schemes employed in this study are reference-free, the monitoring signal was not used for signal processing. The receiver array was placed 37 metres away from the transmitter and consisted of a ULA with

vertically polarised Ubiquiti UMA-D antennas (Ubiquiti Inc., New York, NY, USA), spaced at

cm intervals. Reception was handled by two NI USRP-2955 devices National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) (designated A and B), each offering four independent receiving channels. The received signals were individually down-converted, digitised, and forwarded to a host PC for offline processing. Although the two devices operated without a shared reference clock, thus lacking phase synchronisation, coarse time alignment and amplitude calibration were achieved using the direct-path signal from the transmitter.

Due to the chosen inter-element spacing (

), angular ambiguities are expected, limiting the unambiguous detection sector to

, corresponding to an angular range of

. A number of experiments were performed to assess detection performance on human targets and drones moving along paths that intersect the baseline at its midpoint. A summary of test scenarios is provided in

Table 7, and the corresponding geometrical configurations are depicted in

Figure 12. It is worth noting that, given the limited range of bistatic delays in the adopted short-baseline geometry, target fading due to waveform autocorrelation is not expected. Therefore, the sub-band approach is not adopted in either of the tests, as it would not provide any significant advantage and would instead cause attenuation in the received signal power.

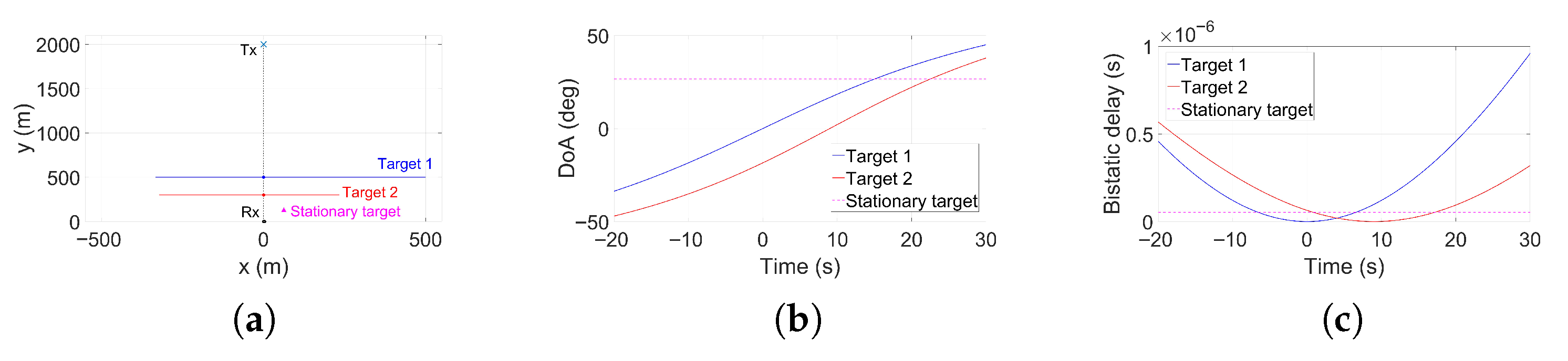

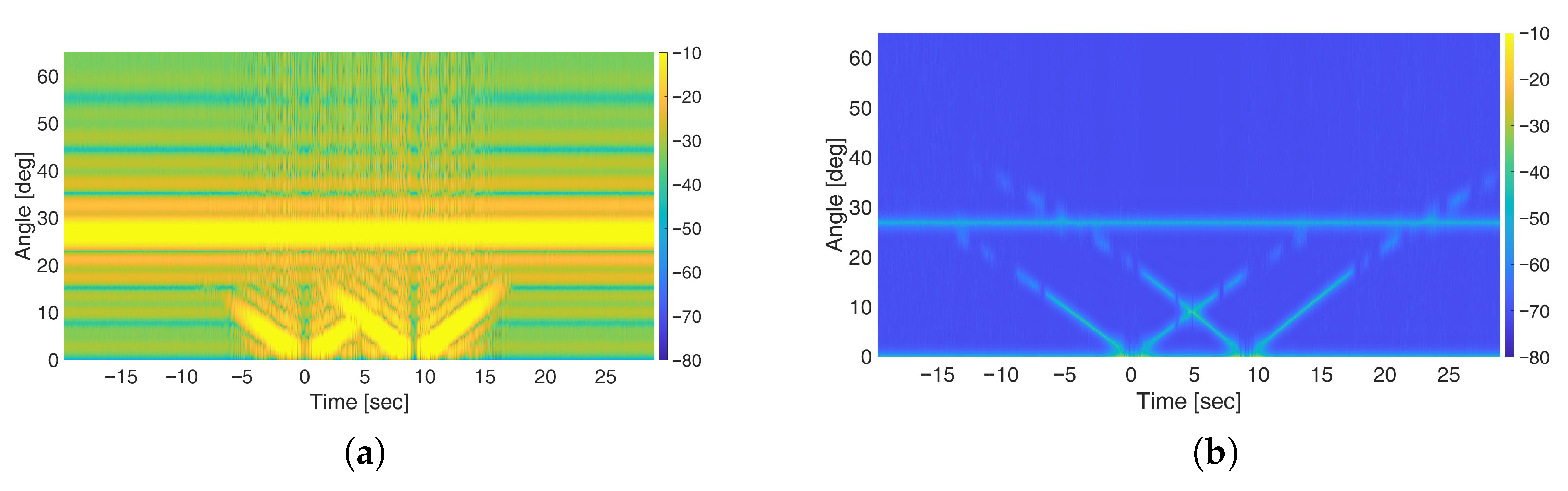

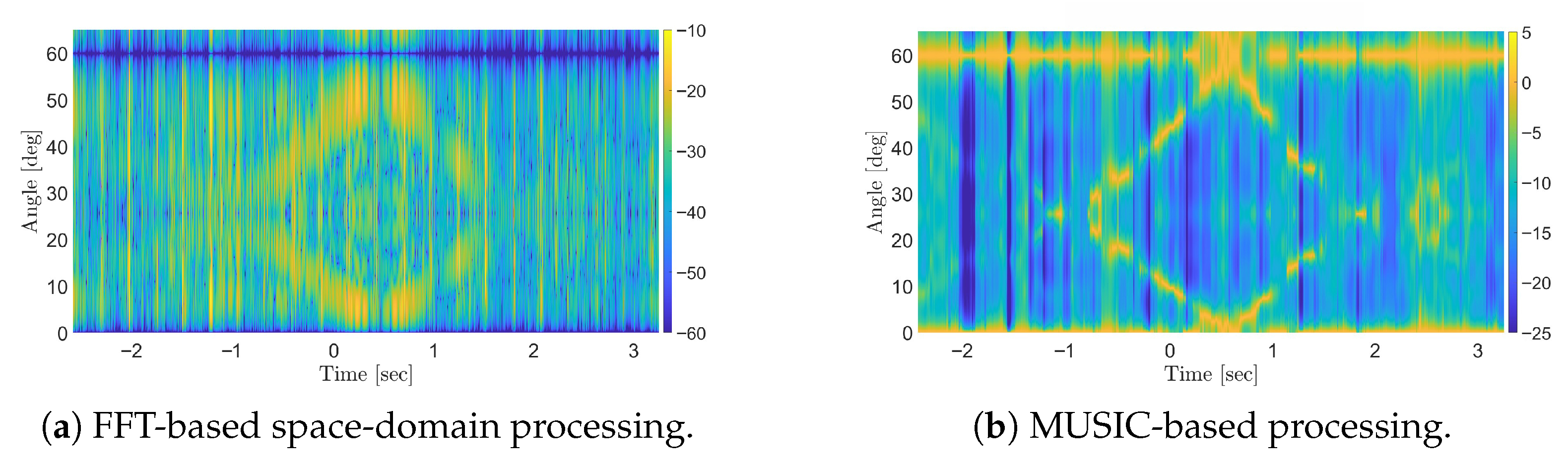

In Test 1, a single moving target scenario is examined. We set

to account for the moving target and the direct path signal and

samples were used for the estimation of the covariance matrix. The MC-FSR results obtained with FFT-based space-domain processing and the MUSIC-based processing are shown in

Figure 13. Despite the strong multipath in the environment and inherent experimental uncertainties, both approaches successfully reveal the target’s presence through the characteristic V-shaped signature thus demonstrating the practical effectiveness of the considered amplitude-based sensing. However, the angular resolution and the clarity of the target signature achieved using MUSIC is substantially superior to that of FFT-based space-domain processing, underscoring its ability to resolve closely spaced features more precisely. These findings highlight the advantages of the MUSIC-based MC-FSR method, especially under hardware-constrained setups, such as those using a small RX array with

elements. It is also important to note that insufficient spatial sampling, combined with the sign ambiguity, causes spectral folding effects that introduce spurious peaks in the angular domain. Notably, since no cancellation is performed in the MUSIC-based approach, the replica of the direct path signal appears approximately at 60° in the output map while there appears a null in the FFT-based output.

To assess the system’s capability to detect small, weak targets, Test 2 was conducted using the same experimental parameters, with a small drone (DJI Mavic Pro) acting as the target. We set

and

for this test, too. As illustrated in

Figure 14, the target signature is barely distinguishable with a MC-FSR using FFT-based beamforming due to its low signal power. In contrast, applying the MUSIC algorithm not only enhances angular resolution but also improves the target’s visibility against background clutter. These results further validate the effectiveness and superiority of MUSIC-based processing scheme for improving the detection of weak targets with MC-FSR, compared to the original FFT-based space-domain approach.

To further evaluate the MUSIC-based approach performance in MC-FSR operated in multi-target scenarios, an experiment was conducted involving two human targets running (one after the other) and intersecting the baseline orthogonally (

Figure 12b). All other processing parameters were kept the same, except for the assumed number of DoFs, which was set to

to account for the two targets and the direct-path signal. The results, shown in

Figure 15, reveal that the MC-FSR using the FFT-based space-domain processing scheme struggles to resolve the two targets, especially when their signatures intersect in the angle–time map. In contrast, the MC-FSR exploiting the MUSIC-based scheme successfully distinguishes between them, clearly demonstrating its superior performance and better angular resolution. Importantly, even under such constrained and borderline conditions with only

RX elements and

DoFs, the MUSIC algorithm maintains effective multi-target resolution. Note that here, given the use of an OFDM waveform in fullband (which was shown beneficial in decorrelating signals) and the limited available DoFs, spatial smoothing turns to be both unnecessary and impractical. These findings further support the earlier analysis that spatial smoothing is not strictly required when using OFDM in such conditions.