Hi-MDTCN: Hierarchical Multi-Scale Dilated Temporal Convolutional Network for Tool Condition Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- This paper proposes a Bidirectional Temporal Convolutional Module (Bi-TCN), which employs a symmetric padding strategy to achieve non-causal modeling, enabling feature extraction to simultaneously capture both historical and future contextual information. Compared to the causal relationship constraints of traditional TCN, this module significantly enhances the temporal feature expression capability.

- (b)

- For multi-source sensor data feature extraction, a lightweight intra-segment attention mechanism is designed, dynamically enhancing key wear features through channel attention weights. This mechanism can improve feature expression capability without increasing model complexity, effectively enhancing model robustness under complex working conditions.

- (c)

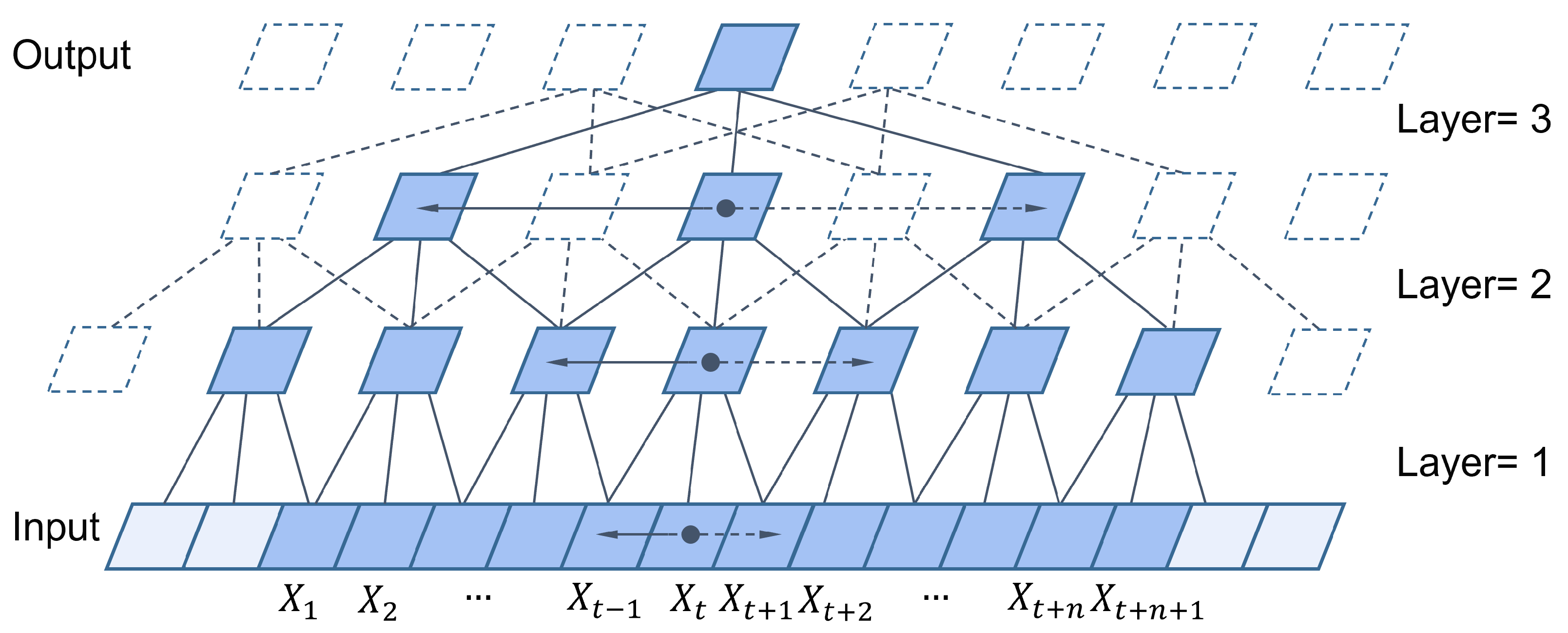

- The paper proposes a Hierarchical Multi-scale Temporal Network Hi-MDTCN, and designs a two-stage hierarchical processing strategy for intra-segment and inter-segment in the network. Intra-segment processing employs three-way parallel convolutions to process multi-source signals and introduces channel attention mechanisms to strengthen key features. Inter-segment processing adopts multi-scale dilated convolutional mechanisms to capture multi-scale patterns in the tool wear evolution process. The architecture achieves collaborative modeling of local features and global trends through the integration of time series slices.

2. Related Work

3. Preliminaries

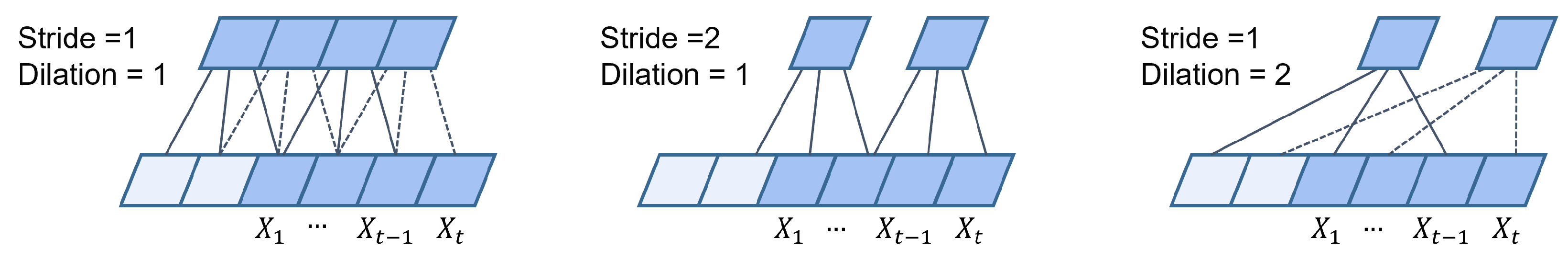

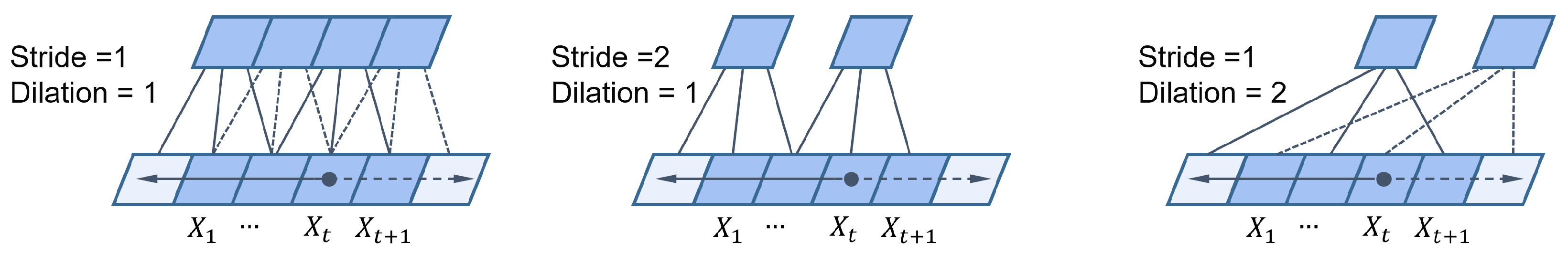

3.1. Causal Convolutions

3.2. Dilated Convolution

4. Methodology and Proposed Model

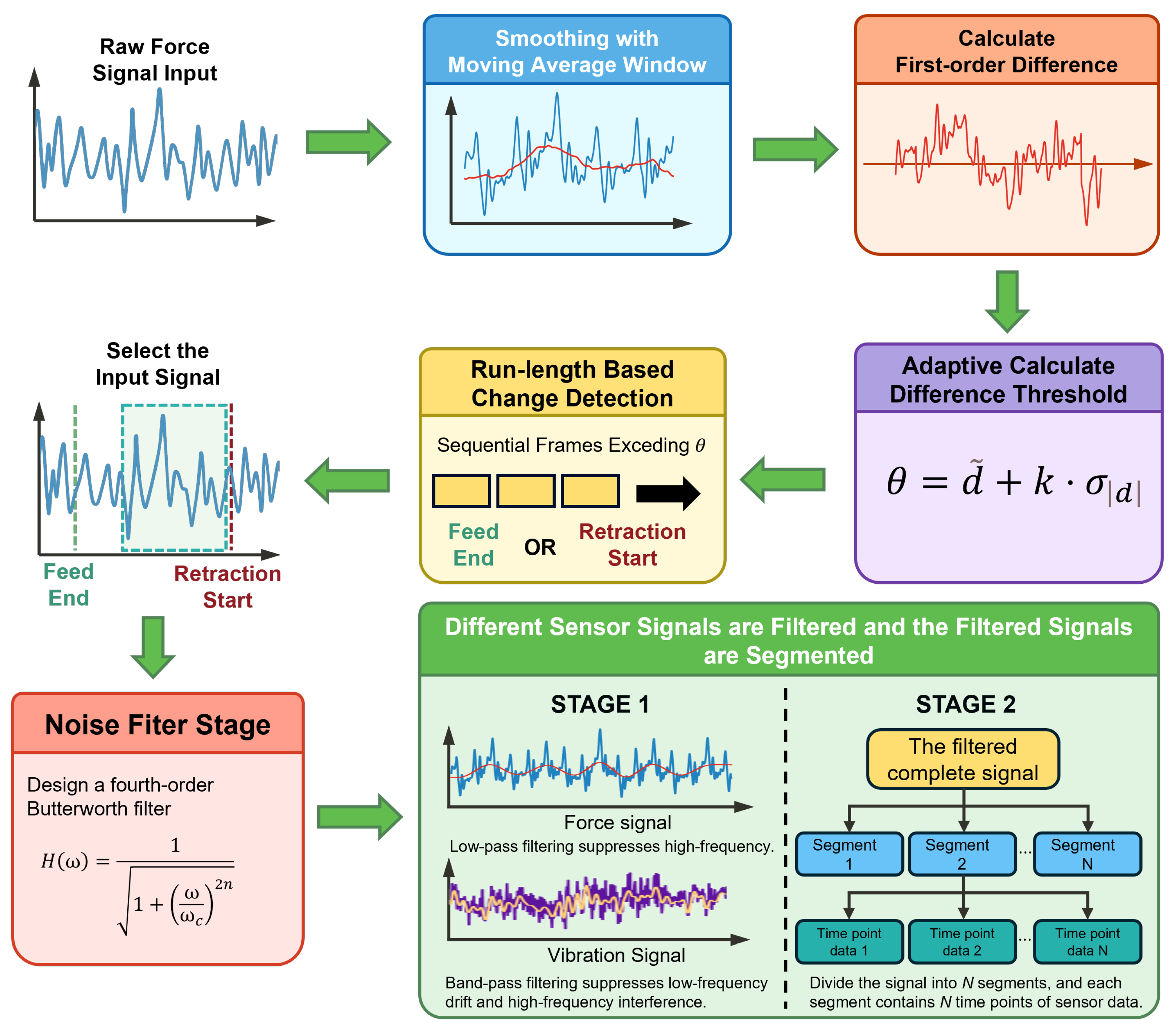

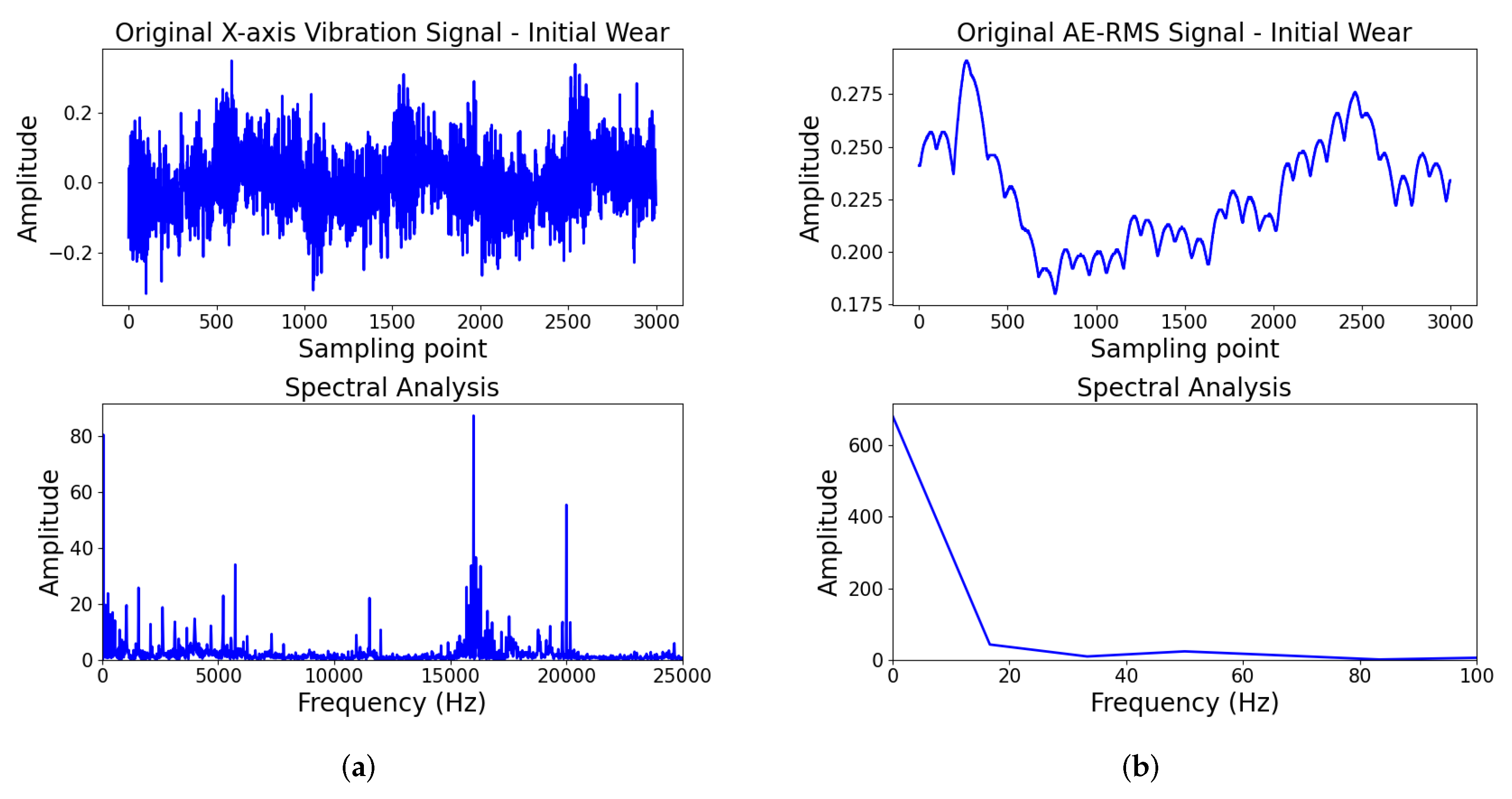

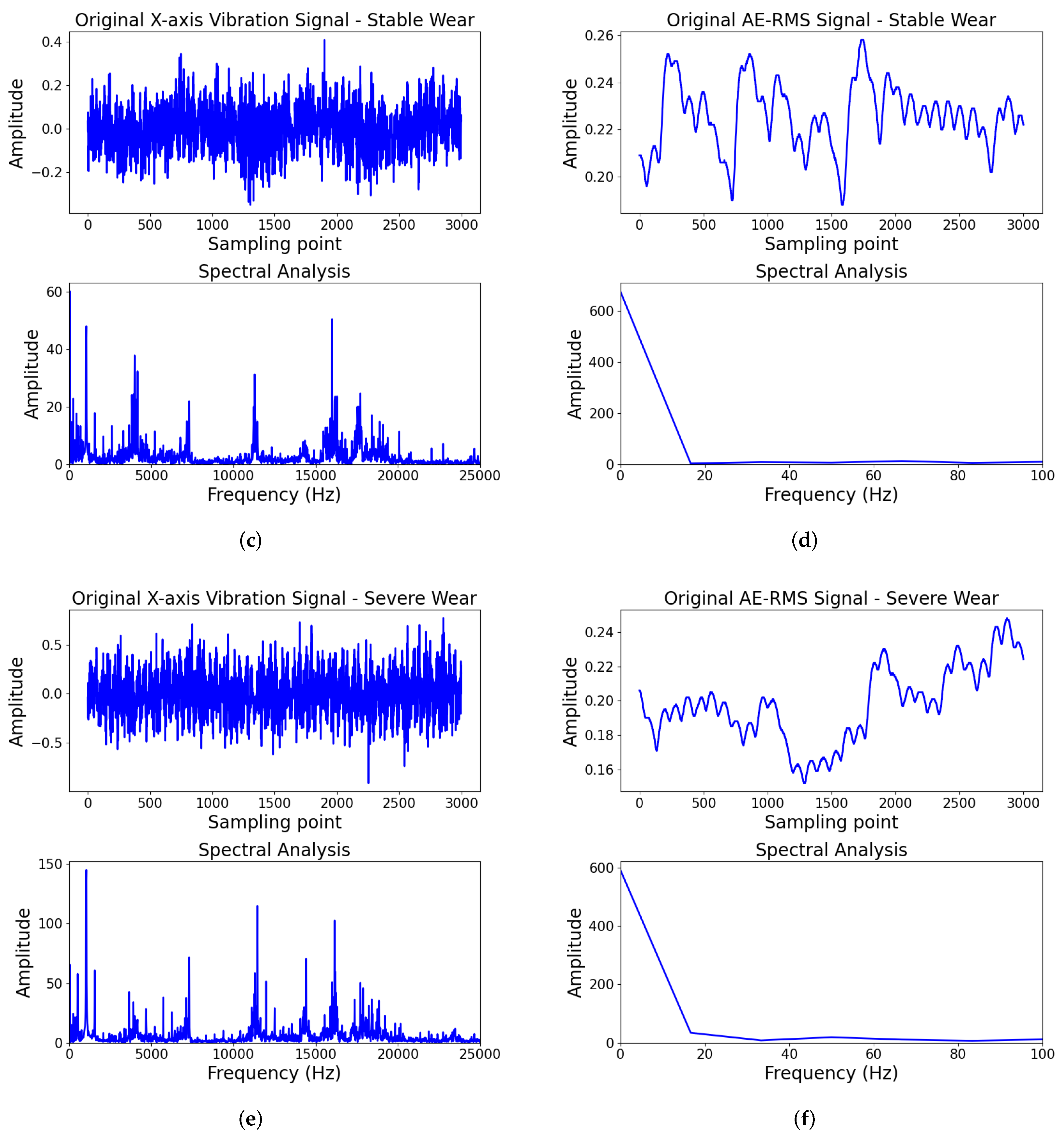

4.1. Signal Preprocessing

4.2. Intra-Segment Feature Extraction

4.3. Inter-Segment Temporal Modeling

5. Experimental Study

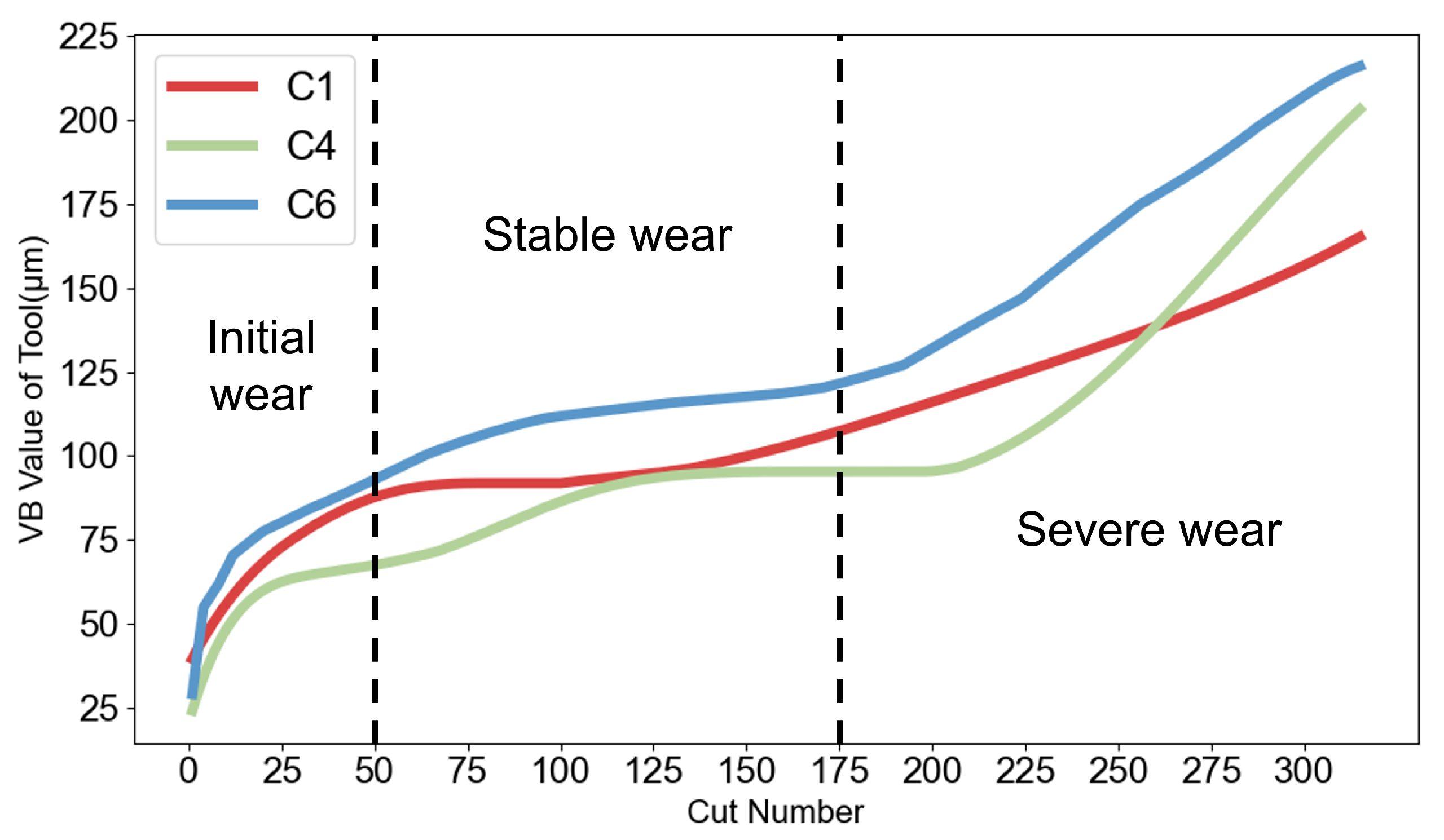

5.1. Dataset Description

5.2. Data Preprocessing

5.3. Results Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Algorithm A1 The Proposed Framework for Hi-MDTCN |

|

References

- Chen, M.; Mao, J.; Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, W. In-situ tool wear condition monitoring during the end milling process based on dynamic mode and abnormal evaluation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; Gupta, M.K.; da Silva, L.R.R.; Kiran, M.; Khanna, N.; Krolczyk, G.M. Application of measurement systems in tool condition monitoring of Milling: A review of measurement science approach. Measurement 2022, 199, 111503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-J.; Chen, J.-W.; Jhuang, J.-P.; Tsai, M.-S.; Hung, C.-L.; Li, K.-M.; Young, H.-T. Integrating object detection and image segmentation for detecting the tool wear area on stitched image. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhou, J.; Li, E.; Wang, M.; Jin, T. Local-feature and global-dependency based tool wear prediction using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.Y.; Chuah, J.H.; Yap, H.J. Technical data-driven tool condition monitoring challenges for CNC milling: A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 107, 4837–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Zhu, K. Application of physics-guided deep learning model in tool wear monitoring of high-speed milling. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 111949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasilingam, S.; Yang, R.; Singh, S.K.; Farahani, M.A.; Rai, R.; Wuest, T. Physics-based and data-driven hybrid modeling in manufacturing: A review. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2024, 12, 2305358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Chen, N.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, L. Hierarchical temporal transformer network for tool wear state recognition. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 58, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntemi, M.; Paraschos, S.; Karakostas, A.; Gialampoukidis, I.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. Infrastructure monitoring and quality diagnosis in CNC machining: A review. Cirp J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2022, 38, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xue, W. Review of tool condition monitoring methods in milling processes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 96, 2509–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Shao, J.; Guo, W.; Li, W.; Zhu, J.; Fang, D. Hybrid machine learning-enabled multi-information fusion for indirect measurement of tool flank wear in milling. Measurement 2023, 206, 112255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Hassan, M.; M’Saoubi, R.; Attia, H. Tool Condition Monitoring for High-Performance Machining Systems—A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, S.; Rahman Rashid, R.A.; Stephens, G.; Papageorgiou, A.; Navarro-Devia, J.; Hägglund, S.; Palanisamy, S. Predicting cutting tool life: Models, modelling, and monitoring. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 3037–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yao, C.; Tan, L.; Cui, M.; Ren, J.; Luo, M.; Ding, W.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J. Research progress on intelligent monitoring of machining condition based on indirect method. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 67, 103518. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, W.; Zou, Y.; Chen, N. Study on tool wear state recognition algorithm based on spindle vibration signals collected by homemade tool condition monitoring ring. Measurement 2023, 223, 113787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Devia, J.H.; Chen, Y.; Dao, D.V.; Li, H. Chatter detection in milling processes—A review on signal processing and condition classification. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 3943–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntoğlu, M.; Salur, E.; Gupta, M.K.; Sarıkaya, M.; Pimenov, D.Y. A state-of-the-art review on sensors and signal processing systems in mechanical machining processes. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 116, 2711–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tian, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Han, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, D. Identification of grinding wheel wear states using AE monitoring and HHT-RF method. Wear 2025, 562, 205668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.-Q.; Doan, H.-P.; Vu, V.Q.; Vu, L.T. Machine learning and IoT-based approach for tool condition monitoring: A review and future prospects. Measurement 2023, 207, 112351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tian, Y.; Hu, X.; Han, J.; Liu, B. Integrated assessment and optimization of dual environment and production drivers in grinding. Energy 2023, 272, 127046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hu, S.; Guo, W.; Tang, H. Abrasive tool wear prediction based on an improved hybrid difference grey wolf algorithm for optimizing SVM. Measurement 2022, 187, 110247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoz, B.; Shaikh, H.N.E.; Mulani, S.M.; Kumar, A.; Rajasekharan, S.G. Random forests based classification of tool wear using vibration signals and wear area estimation from tool image data. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 3069–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Qin, C.; Guan, F.; Su, H. A Tool Wear Monitoring Method Based on WOA and KNN for Small-Deep Hole Drilling. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Symposium on Computer Technology and Information Science (ISCTIS), Guilin, China, 4–6 June 2021; pp. 284–287. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, V.; Sassani, F. A review on deep learning in machining and tool monitoring: Methods, opportunities, and challenges. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 2683–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Pardeshi, S.S.; Patange, A.D.; Jegadeeshwaran, R. Deep Learning Algorithms for Tool Condition Monitoring in Milling: A Review. J. Physics Conf. Ser. 2021, 1969, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhu, K.; Wang, G. Micro-milling tool wear monitoring under variable cutting parameters and runout using fast cutting force coefficient identification method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 111, 3175–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Lei, J.; Li, X.; Tian, F. Tool wear monitoring with vibration signals based on short-time Fourier transform and deep convolutional neural network in milling. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9976939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Jiao, F. Tool wear status monitoring under laser-ultrasonic compound cutting based on acoustic emission and deep learning. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 2411–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagga, P.J.; Chavda, B.; Modi, V.; Makhesana, M.A.; Patel, K.M. Indirect tool wear measurement and prediction using multi-sensor data fusion and neural network during machining. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 56, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Cao, Y. Tool wear prediction based on multisensor data fusion and machine learning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 5213–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Li, H.; Liu, B.; Peng, D. Deep transfer residual variational autoencoder with multi-sensors fusion for tool condition monitoring in impeller machining. Measurement 2022, 204, 112028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, X.; Yue, C.; Zhao, M.; Wei, X.; Wang, L. Tool wear identification and prediction method based on stack sparse self-coding network. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 68, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, K.; Ge, Y.; Yu, L.; Fu, Z. Tool wear monitoring based on multi-kernel Gaussian process regression and Stacked Multilayer Denoising AutoEncoders. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 186, 109851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, S.; Kumar, S.; Bongale, A.; Kotecha, K.; Selvachandran, G.; Suganthan, P.N. Tool wear prediction using long short-term memory variants and hybrid feature selection techniques. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 6611–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, C.; Hu, B.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Guo, K. Tool wear monitoring using a novel parallel BiLSTM model with multi-domain features for robotic milling Al7050-T7451 workpiece. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 129, 1883–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, K.; Fu, H. Identification of tool wear status using multi-sensor signals and improved gated recurrent unit. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, X.; Wei, X.; Guo, B.; Jia, R. A variable modal decomposition and BiGRU-based tool wear monitoring method based on non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 38, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Jia, M.; Tian, R. A novel temporal convolutional network with residual self-attention mechanism for remaining useful life prediction of rolling bearings. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 215, 107813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J. Multisensor-based tool wear diagnosis using 1D-CNN and DGCCA. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 4448–4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Wang, C.; Yang, G.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C. An Improved ResNet-1d with Channel Attention for Tool Wear Monitor in Smart Manufacturing. Sensors 2023, 23, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yuan, R.; Lv, Y.; Li, L.; Song, H. A Novel Multivariate Cutting Force-Based Tool Wear Monitoring Method Using One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2022, 22, 8343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, X.; Wang, T.; He, Y. Tool Wear Condition Monitoring Method Based on Deep Learning with Force Signals. Sensors 2023, 23, 4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Incecik, A.; Gupta, M.K.; Królczyk, G.M.; Gardoni, P. A novel ensemble deep learning model for cutting tool wear monitoring using audio sensors. J. Manuf. Processes 2022, 79, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.-Q.; Liu, M.-K.; Tran, Q.-V. Milling chatter detection using scalogram and deep convolutional neural network. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 107, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zou, S.; Zhao, T.; Su, X. MDFA-Net: Multi-Scale Differential Feature Self-Attention Network for Building Change Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Hou, L.; Yi, S. Overview of Tool Wear Monitoring Methods Based on Convolutional Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Z.; Gao, R.X.; Guo, Y. Heterogeneous data-driven hybrid machine learning for tool condition prognosis. CIRP Ann. 2019, 68, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Fu, H.; Han, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jin, H. Intelligent tool wear prediction based on Informer encoder and stacked bidirectional gated recurrent unit. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 77, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Jia, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.; Tan, J. Tool wear estimation using a CNN-transformer model with semi-supervised learning. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 125010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.; Gulcehre, C.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Empirical Evaluation of Gated Recurrent Neural Networks on Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A. Long Short-Term Memory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Hao, Q.; Yang, H.; Wei, J. Tool wear state recognition based on gradient boosting decision tree and hybrid classification RBM. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 110, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Equipment Type | Experimental Equipment | Experimental Projects | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNC milling machine | Roders Tech RFM760 | Spindle speed (r/min) | 10,400 |

| Tool type | 3-tooth ball nose milling cutter | Feed rate (mm/min) | 1555 |

| Workpiece material | Stainless steel HRC52 | Cutting width (mm) | 0.125 |

| Force sensor | Kistler 9265B dynamometer | Cutting depth (mm) | 0.2 |

| Charge amplifier | Kistler 5019A charge amplifier | Tool feeding amount (mm) | 0.001 |

| Vibration sensor | Kistler 8636c acceleration sensor | Sampling frequency (kHz) | 50 |

| AE sensor | Kistler acoustic emission sensor | Milling method | Climb milling |

| Wear measuring device | LEICA MZ12 microscope | Cooling method | Dry cutting |

| Data acquisition card | NI DAQ data acquisition card |

| Datasets | Training Datasets | Test Datasets |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | C1–C4 | C6 |

| T2 | C4–C6 | C1 |

| T3 | C1–C6 | C4 |

| No. | Stage | Module Name | Input Shape | Output Shape | Input Channels | Output Channels | Kernel Size | Dilation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Signal Preprocessing | Lowpass Filter (Force) | [N, 3] | [N, 3] | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | Bandpass Filter (Vibration) | [N, 3] | [N, 3] | - | - | - | - | |

| 3 | None Filter (AE) | [N, 1] | [N, 1] | - | - | - | - | |

| 4 | Segmentation | [50,000, 7] | [50, 7, 1000] | - | - | - | - | |

| 5 | Force Signal Branch | Conv1d Block | [B × 50, 3, 1000] | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | 3 | 32 | 3 | 1 |

| 6 | Channel Attention | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | 32 | 32 | 3 | - | |

| 7 | MaxPool | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | [B × 50, 32, 1] | 32 | 32 | - | - | |

| 8 | Vibration Signal Branch | Conv1d Block | [B × 50, 3, 1000] | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | 3 | 32 | 3 | 1 |

| 9 | Channel Attention | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | 32 | 32 | 3 | - | |

| 10 | MaxPool | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | [B × 50, 32, 1] | 32 | 32 | - | - | |

| 11 | Acoustic Emission Branch | Conv1d Block | [B × 50, 1, 1000] | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | 1 | 32 | 3 | 1 |

| 12 | MaxPool | [B × 50, 32, 1000] | [B × 50, 32, 1] | 32 | 32 | - | - | |

| 13 | Segment Feature Fusion | Concatenation | [B × 50, 32, 1] × 3 | [B × 50, 96, 1] | 96 | 96 | - | - |

| 14 | Conv1d Block #1 | [B × 50, 96, 1] | [B × 50, 32, 1] | 96 | 32 | 3 | 1 | |

| 15 | Channel Attention #1 | [B × 50, 32, 1] | [B × 50, 32, 1] | 32 | 32 | 3 | - | |

| 16 | Conv1d Block #2 | [B × 50, 32, 1] | [B × 50, 32, 1] | 32 | 32 | 3 | 1 | |

| 17 | Channel Attention #2 | [B × 50, 32, 1] | [B × 50, 32, 1] | 32 | 32 | 3 | - | |

| 18 | Reshape to Segments | [B × 50, 32, 1] | [B, 32, 50] | 32 | 32 | - | - | |

| 19 | Segment Temporal Modeling | ResidualDCBlock (Dilation = 1) | [B, 32, 50] | [B, 32, 50] | 32 | 32 | 3 | 1 |

| 20 | ResidualDCBlock (Dilation = 2) | [B, 32, 50] | [B, 32, 50] | 32 | 32 | 3 | 2 | |

| 21 | ResidualDCBlock (Dilation = 4) | [B, 32, 50] | [B, 32, 50] | 32 | 32 | 3 | 4 | |

| 22 | MaxPool | [B, 32, 50] | [B, 32, 1] | 32 | 32 | - | - | |

| 23 | Fully Connected | [B, 32] | [B, 3] | 32 | 3 | - | - |

| Models | T1 (%) | T2 (%) | T3 (%) | Mean ± Std (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D-CNN with DGCCA [39] | 88.54 | 90.80 | 90.80 | 90.05 ± 1.30 |

| CaAt-ResNet-1d [40] | 86.54 | 90.23 | 89.50 | 88.76 ± 1.95 |

| Informer [48] | 90.02 | 89.92 | 91.52 | 90.49 ± 0.89 |

| CNN-Transformer [49] | 89.52 | 86.54 | 90.04 | 88.70 ± 1.89 |

| Transformer [50] | 90.02 | 85.06 | 89.52 | 88.20 ± 2.73 |

| GRU [51] | 83.63 | 85.72 | 84.81 | 84.72 ± 1.05 |

| LSTM [52] | 83.52 | 82.49 | 81.62 | 82.54 ± 0.95 |

| GHCRBM [53] | 87.81 | 90.92 | 62.23 | 80.32 ± 15.75 |

| Proposed model | 93.02 | 91.43 | 93.65 | 92.70 ± 0.93 |

| Model Description | T1 (%) | T2 (%) | T3 (%) | Mean ± Std (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (without channel attention) | 89.52 | 90.16 | 91.11 | 90.26 ± 0.65 |

| Model 2 (TCN instead Bi-TCN with channel attention) | 91.75 | 92.23 | 88.25 | 90.74 ± 1.77 |

| Model 3 (TCN instead Bi-TCN without channel attention) | 86.03 | 84.76 | 85.71 | 85.50 ± 0.54 |

| Proposed model | 93.02 | 91.43 | 93.65 | 92.70 ± 0.93 |

| Indicators | Stage | T1 | T2 | T3 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | - | 0.9302 | 0.9143 | 0.9365 | 0.9270 |

| Precision | Initial | 0.9250 | 0.9787 | 1.0000 | 0.9679 |

| Stable | 0.8759 | 0.9623 | 0.9817 | 0.9399 | |

| Recall | Severe | 0.9714 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9905 |

| Specificity | Severe | 0.9886 | 0.8743 | 0.8971 | 0.9200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chai, A.; Fang, Z.; Lian, M.; Huang, P.; Guo, C.; Yin, W.; Wang, L.; He, E.; Li, S. Hi-MDTCN: Hierarchical Multi-Scale Dilated Temporal Convolutional Network for Tool Condition Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 7603. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247603

Chai A, Fang Z, Lian M, Huang P, Guo C, Yin W, Wang L, He E, Li S. Hi-MDTCN: Hierarchical Multi-Scale Dilated Temporal Convolutional Network for Tool Condition Monitoring. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7603. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247603

Chicago/Turabian StyleChai, Anying, Zhaobo Fang, Mengjia Lian, Ping Huang, Chenyang Guo, Wanda Yin, Lei Wang, Enqiu He, and Siwen Li. 2025. "Hi-MDTCN: Hierarchical Multi-Scale Dilated Temporal Convolutional Network for Tool Condition Monitoring" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7603. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247603

APA StyleChai, A., Fang, Z., Lian, M., Huang, P., Guo, C., Yin, W., Wang, L., He, E., & Li, S. (2025). Hi-MDTCN: Hierarchical Multi-Scale Dilated Temporal Convolutional Network for Tool Condition Monitoring. Sensors, 25(24), 7603. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247603