A Dual-Modal Adaptive Pyramid Transformer Algorithm for UAV Cross-Modal Object Detection

Highlights

- A DAP-enhanced YOLOv8 model is proposed to address the bottlenecks of UAV infrared–visible object detection.

- The DAP module effectively improves multi-scale feature representation, low-light robustness, and cross-modal fusion efficiency.

- The proposed approach achieves superior detection accuracy and real-time performance on DroneVehicle and LLVIP datasets.

- The method provides a practical solution for UAV-based infrared–visible perception in complex and low-illumination environments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Overall Architecture Design

2.1.1. Dual-Modality Independent Dual-Stream Backbone Network

2.1.2. Multi-Scale Feature Pyramid and Detection Head Optimization

2.2. Dual-Modality Adaptive Pyramid Transformer Module

2.2.1. Cross-Modal Feature Encoding Processing

2.2.2. Multi-Head Self-Attention and Modal Interaction Mechanism

2.2.3. Residual Fusion and Preservation of Modal Independence

3. Experiments

3.1. Experimental Setup

3.1.1. Experimental Parameters

3.1.2. Datasets

3.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

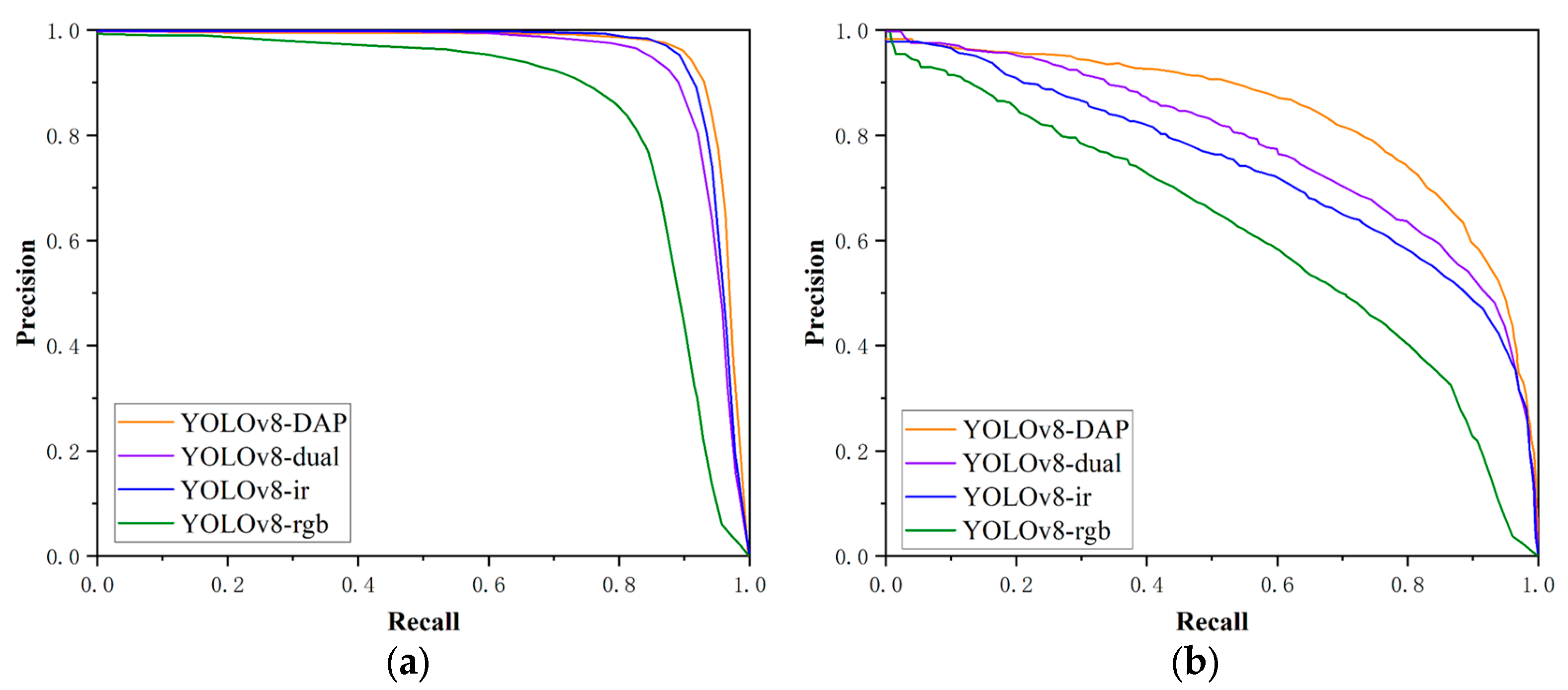

3.2. Ablation Experiments

3.2.1. Ablation Study on Model Components

3.2.2. Ablation Study on Anchor Pooling Size

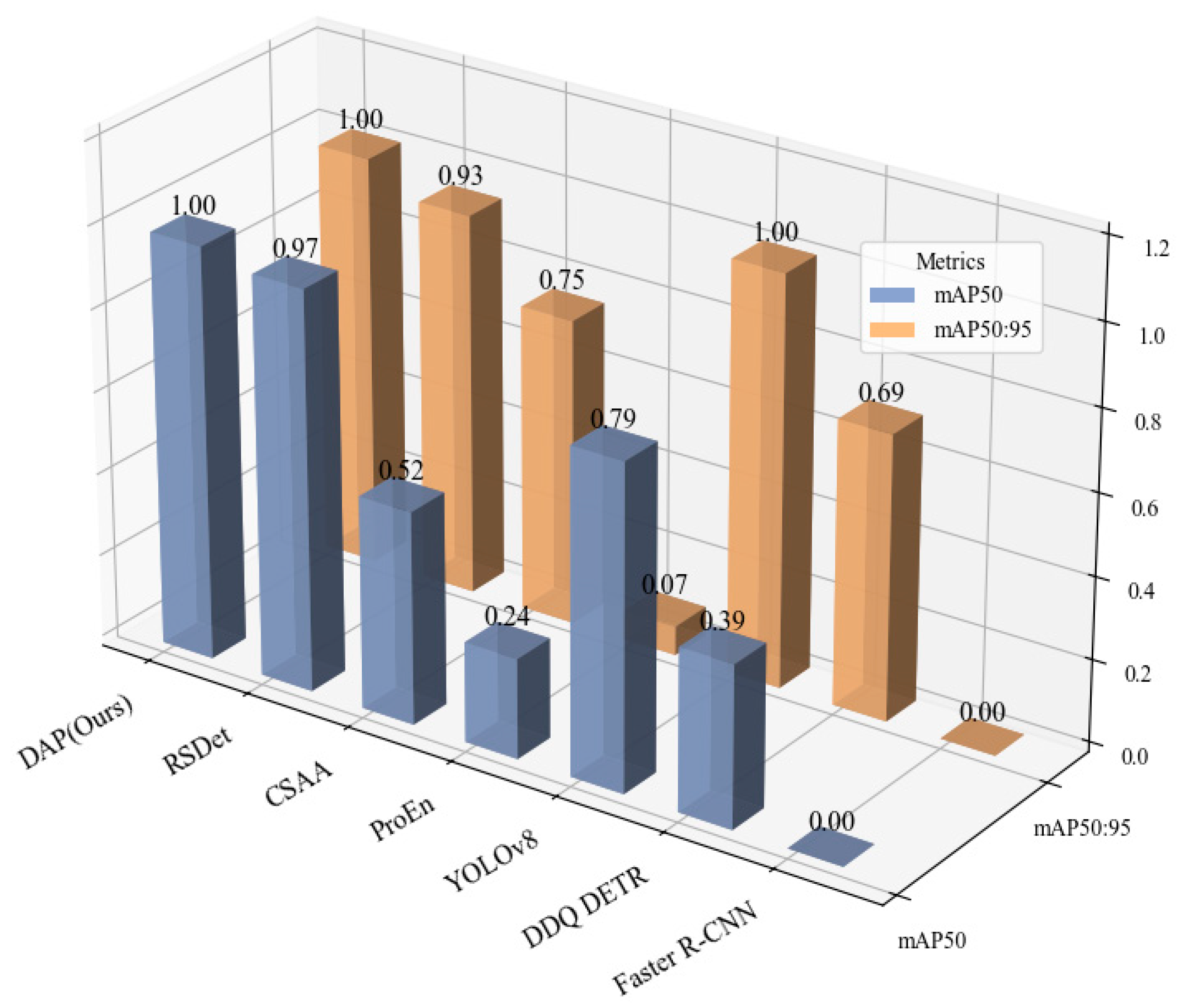

3.3. Comparative Experiments

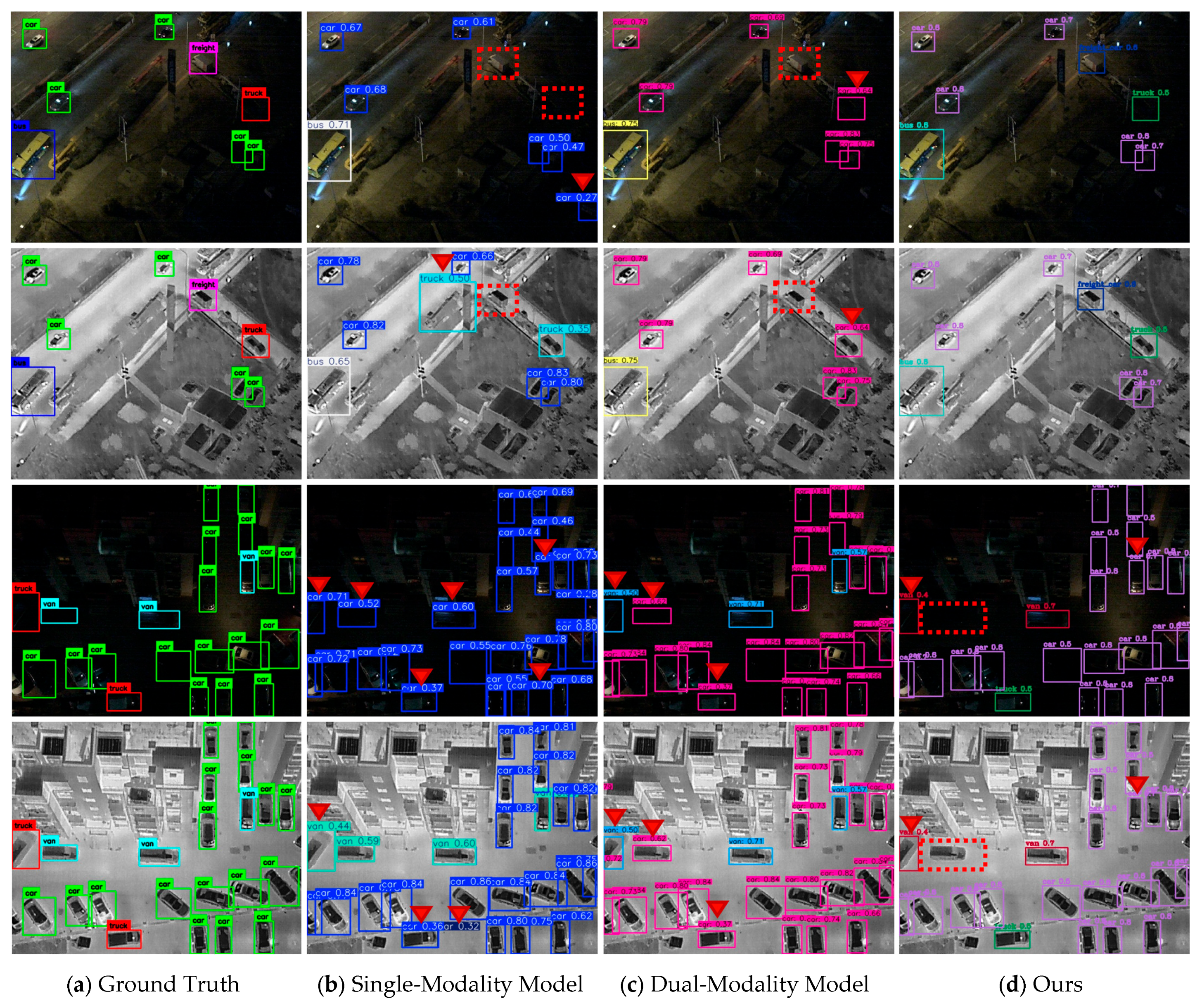

3.3.1. DroneVehicle Datasets

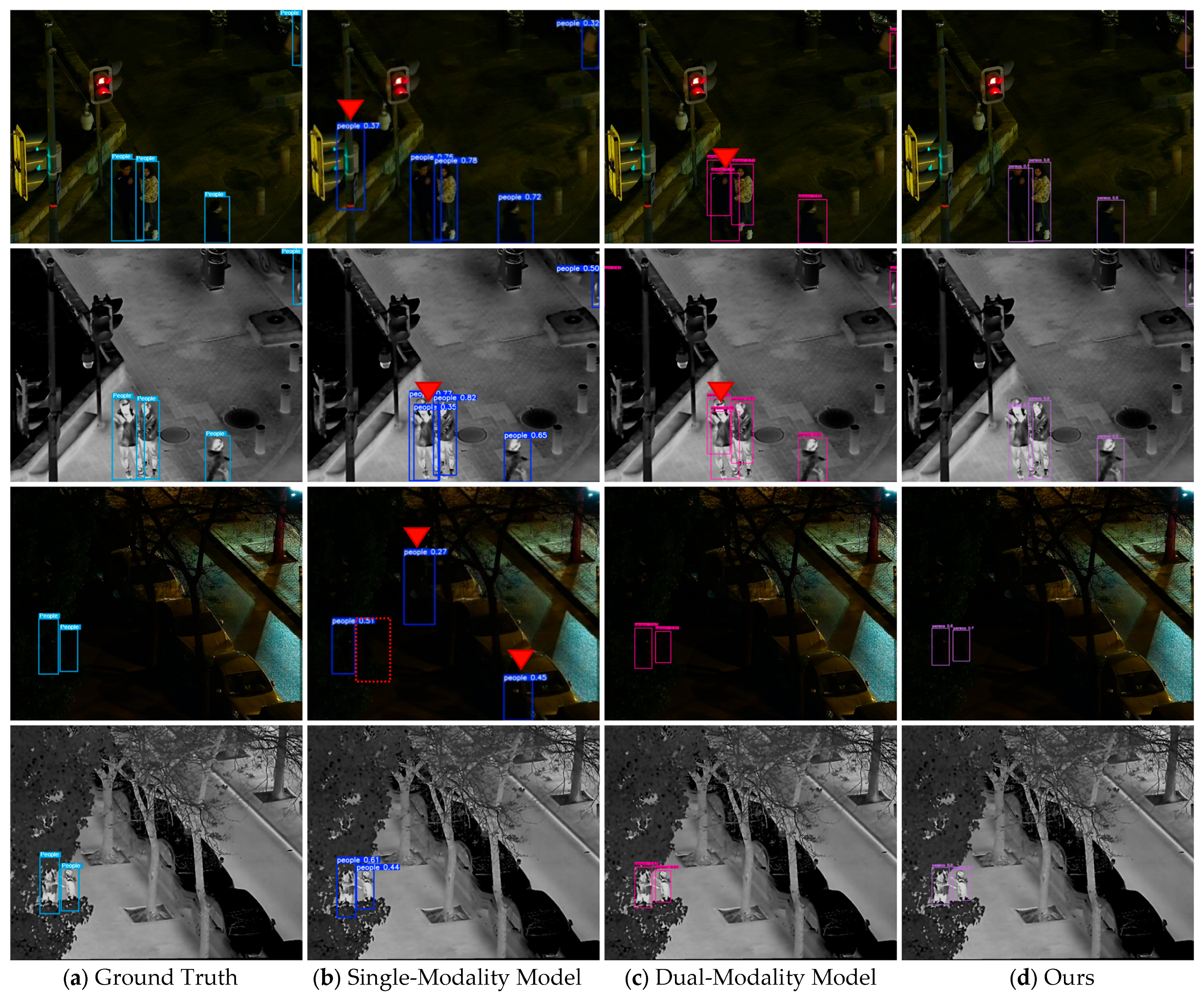

3.3.2. LLVIP Datasets

3.3.3. Complexity Analysis on DroneVehicle

3.3.4. Analysis of Experimental Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Butilă, E.V.; Boboc, R.G. Urban traffic monitoring and analysis using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): A systematic literature review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöcker, C.; Bennett, R.; Nex, F.; Gerke, M.; Zevenbergen, J. Review of the current state of UAV regulations. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. Application of UAV remote sensing in natural disaster monitoring and early warning: An example of flood and mudslide and earthquake disasters. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 85, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koslowski, R.; Schulzke, M. Drones along borders: Border security UAVs in the United States and the European Union. Int. Stud. Perspect. 2018, 19, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakaletsis, E.; Symeonidis, C.; Tzelepi, M.; Mademlis, I.; Tefas, A.; Nikolaidis, N.; Pitas, I. Computer vision for autonomous UAV flight safety: An overview and a vision-based safe landing pipeline example. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douklias, A.; Karagiannidis, L.; Misichroni, F.; Amditis, A. Design and implementation of a UAV-based airborne computing platform for computer vision and machine learning applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, P.; Wergeles, N.; Shang, Y. A survey and performance evaluation of deep learning methods for small object detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 172, 114602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhou, T.; Li, X.; Ren, F. Performance and challenges of 3D object detection methods in complex scenes for autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2022, 8, 1699–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, G.; Fu, X.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, G.; Gao, Y. TLLFusion: An End-to-End Transformer-Based Method for Low-Light Infrared and Visible Image Fusion. In Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV), Urumqi, China, 18–20 October 2024; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Chougule, A.; Narang, P.; Chamola, V.; Yu, F.R. Low-light image enhancement for UAVs with multi-feature fusion deep neural networks. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 3513305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kang, X.; Fang, L.; Hu, J.; Yin, H. Pixel-level image fusion: A survey of the state of the art. Inf. Fusion 2017, 33, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Qi, P.; Chen, S.; Yang, X. Fusion methods for CNN-based automatic modulation classification. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 66496–66504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; Kwon, Y.; Nadar, J.; Fang, J.; Skalski, P.; Michael, K.; Lorna, V.; et al. ultralytics/yolov5: v6.1—TensorRT, TensorFlow Edge TPU and OpenVINO Export and Inference. Zenodo 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Lei, Z.; Liu, Z. Weakly aligned cross-modal learning for multispectral pedestrian detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Dhanaraj, M.; Karnam, S.; Chachlakis, D.G.; Ptucha, R.; Markopoulos, P.P.; Saber, E. YOLOrs: Object detection in multimodal remote sensing imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote. Sens. 2020, 14, 1497–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingyun, F.; Dapeng, H.; Zhaokui, W. Cross-modality fusion transformer for multispectral object detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00273. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Qiao, H.; Huang, K.; Hussain, A. Cross-modality interactive attention network for multispectral pedestrian detection. Inf. Fusion 2019, 50, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Izzat, I.H.; Ziaee, S. GFD-SSD: Gated fusion double SSD for multispectral pedestrian detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.069992019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q. Drone-based RGB-infrared cross-modality vehicle detection via uncertainty-aware learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 6700–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, M.; Tang, W.; Zhou, W. LLVIP: A visible-infrared paired dataset for low-light vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Zhang, M.; Xu, M.; Tang, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. Ship detection in SAR images based on feature enhancement Swin transformer and adjacent feature fusion. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Xia, G.-S. Align deep features for oriented object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote. Sens. 2021, 60, 5602511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; NanoCode012; Kwon, Y.; Xie, T.; Michael, K.; Fang, J.; Imyhxy; et al. ultralytics/yolov5: v6.2—YOLOv5 Classification Models, Apple M1, Reproducibility, ClearML and Deci.ai integrations. Zenodo 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics Yolov8. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Song, Z.; Yang, X.; Lei, Z.; Qiao, H. Weakly aligned feature fusion for multimodal object detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 36, 4145–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Huang, Z.; Wu, G.; Liu, R.; Zhong, W.; Luo, Z. Target-aware dual adversarial learning and a multi-scenario multi-modality benchmark to fuse infrared and visible for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.; Wei, X. C2 former: Calibrated and complementary transformer for RGB-infrared object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5403712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Pang, J.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, W.; Luo, P.; Chen, K. Dense distinct query for end-to-end object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Fromont, E.; Lefevre, S.; Avignon, B. Guided attentive feature fusion for multispectral pedestrian detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–9 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Shi, J.; Ye, Z.; Mertz, C.; Ramanan, D.; Kong, S. Multimodal object detection via probabilistic ensembling. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Bin, J.; Hamari, J.; Blasch, E.; Liu, Z. Multimodal object detection by channel switching and spatial attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Yuan, M.; Jiang, F.; Wang, N.; Wei, X. Removal and selection: Improving RGB-infrared object detection via coarse-to-fine fusion. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10731. [Google Scholar]

| Stage | n | Output Channels | Output Resolution | Feature Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | - | 3 | 320 × 320 | - |

| Ci1 | - | 64 | 160 × 160 | - |

| Ci2 | 3 | 128 | 80 × 80 | - |

| Ci3 | 6 | 256 | 40 × 40 | P3 |

| Ci4 | 6 | 512 | 20 × 20 | P4 |

| Ci5 | 3 | 1024 | 10 × 10 | P5 |

| Configuration | Channel | HSA | RF | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50:95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yolov8 (IR-Channel) | single | × | × | 70.0 | 71.8 | 73.8 | 53.7 |

| Yolov8 (dual-Channel) | dual | × | × | 75.4 | 73.7 | 78.2 | 57.1 |

| Yolov8 (only HSA) | dual | √ | × | 80.6 | 81.9 | 84.7 | 61.4 |

| Yolov8 (only RF) | dual | × | √ | 82.0 | 79.5 | 84.1 | 60.6 |

| Yolov8 (HSA + RF) | dual | √ | √ | 82.0 (↑ 12.0) | 81.6 (↑ 7.9) | 85.0 (↑ 6.8) | 61.2 (↑ 4.1) |

| Pooling Size | mAP50 (%) | mAP50:95 (%) | GFLOPs | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 × 4 | 84.5 | 60.9 | 24.89 | 53.76 |

| 8 × 8 (Ours) | 85.0 | 61.2 | 27.41 | 55.25 |

| 16 × 16 | 84.9 | 60.8 | 37.49 | 53.48 |

| Model | Modality | mAP50 (%) | mAP50:95 (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mono-modality | ||||

| Faster R-CNN | RGB | 55.9 | 28.4 | [11] |

| S2A-Net | RGB | 61.0 | 36.9 | [27] |

| YOLOv5 | RGB | 62.1 | - | [28] |

| YOLOv8 | RGB | 61.3 | 36.8 | [29] |

| Faster R-CNN | IR | 64.2 | 31.1 | [11] |

| S2A-Net | IR | 67.5 | 38.7 | [27] |

| YOLOv5 | IR | 70.7 | - | [28] |

| YOLOv8 | IR | 73.8 | 53.7 | [29] |

| multi-modality | ||||

| UA-CMDet | RGB + IR | 64.0 | 40.1 | [24] |

| AR-CNN | RGB + IR | 71.6 | - | [30] |

| TarDAL | RGB + IR | 72.6 | 43.3 | [31] |

| C2Former | RGB + IR | 74.2 | 42.8 | [32] |

| DAP (Ours) | RGB + IR | 85.0 ± 0.1 | 61.2 ± 0.3 | This work |

| Model | Modality | mAP50 (%) | mAP50:95 (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mono-modality | ||||

| Faster R-CNN | RGB | 88.8 | 47.5 | [11] |

| DDQ DETR | RGB | 88.3 | 47.0 | [33] |

| YOLOv5 | RGB | 90.8 | 50.0 | [28] |

| YOLOv8 | RGB | 91.9 | 54.0 | [29] |

| Faster R-CNN | IR | 92.6 | 50.7 | [11] |

| DDQ DETR | IR | 93.9 | 58.6 | [33] |

| YOLOv5 | IR | 94.6 | 61.9 | [28] |

| YOLOv8 | IR | 95.2 | 62.1 | [29] |

| multi-modality | ||||

| GAFF | RGB + IR | 94.0 | 55.8 | [34] |

| ProEn | RGB + IR | 93.4 | 51.5 | [35] |

| CSAA | RGB + IR | 94.3 | 59.2 | [36] |

| RSDet | RGB + IR | 95.8 | 61.3 | [37] |

| DAP (Ours) | RGB + IR | 95.9 ± 0.1 | 62.1 ± 0.1 | This work |

| Model | mAP50 (%) | mAP50:95 (%) | GFLOPs | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8-IR | 73.8 | 53.7 | 8.75 | 3.15 M |

| YOLOv8-dual | 78.2 | 57.1 | 11.4 | 4.28 M |

| C2Former | 74.2 | 42.8 | 100.9 | 132.5 M |

| CFT | 79.1 | 59.4 | 224.4 | 206.3 M |

| DAP (Ours) | 85.0 ± 0.1 | 61.2 ± 0.3 | 27.41 | 28.51 M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, N.; Tu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhu, X. A Dual-Modal Adaptive Pyramid Transformer Algorithm for UAV Cross-Modal Object Detection. Sensors 2025, 25, 7541. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247541

Li Q, Yang M, Zhang X, Wang N, Tu X, Liu X, Zhu X. A Dual-Modal Adaptive Pyramid Transformer Algorithm for UAV Cross-Modal Object Detection. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7541. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247541

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Qiqin, Ming Yang, Xiaoqiang Zhang, Nannan Wang, Xiaoguang Tu, Xijun Liu, and Xinyu Zhu. 2025. "A Dual-Modal Adaptive Pyramid Transformer Algorithm for UAV Cross-Modal Object Detection" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7541. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247541

APA StyleLi, Q., Yang, M., Zhang, X., Wang, N., Tu, X., Liu, X., & Zhu, X. (2025). A Dual-Modal Adaptive Pyramid Transformer Algorithm for UAV Cross-Modal Object Detection. Sensors, 25(24), 7541. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247541