3.1. Assembly of Schwarzschild Imaging Spectrometer

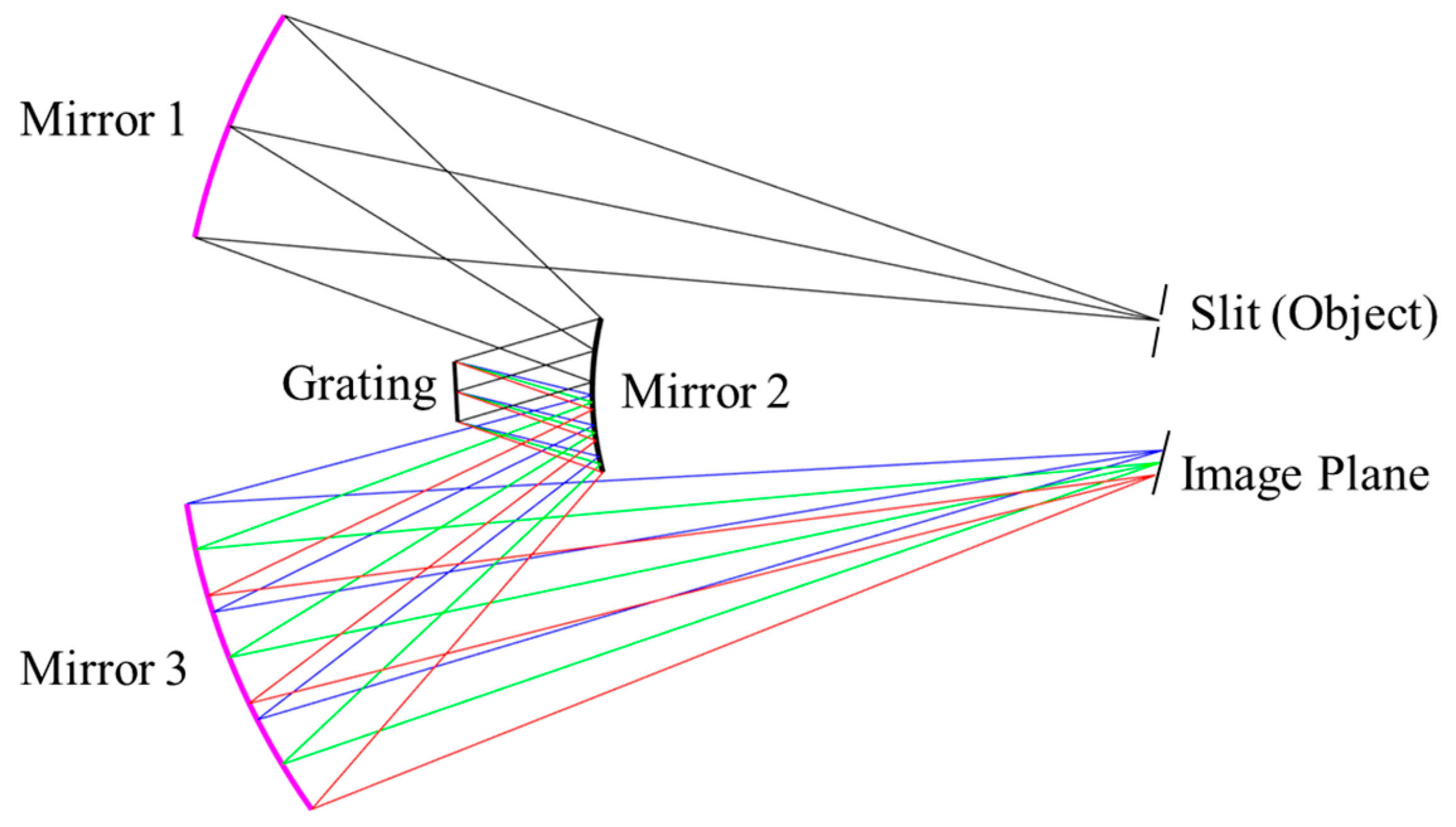

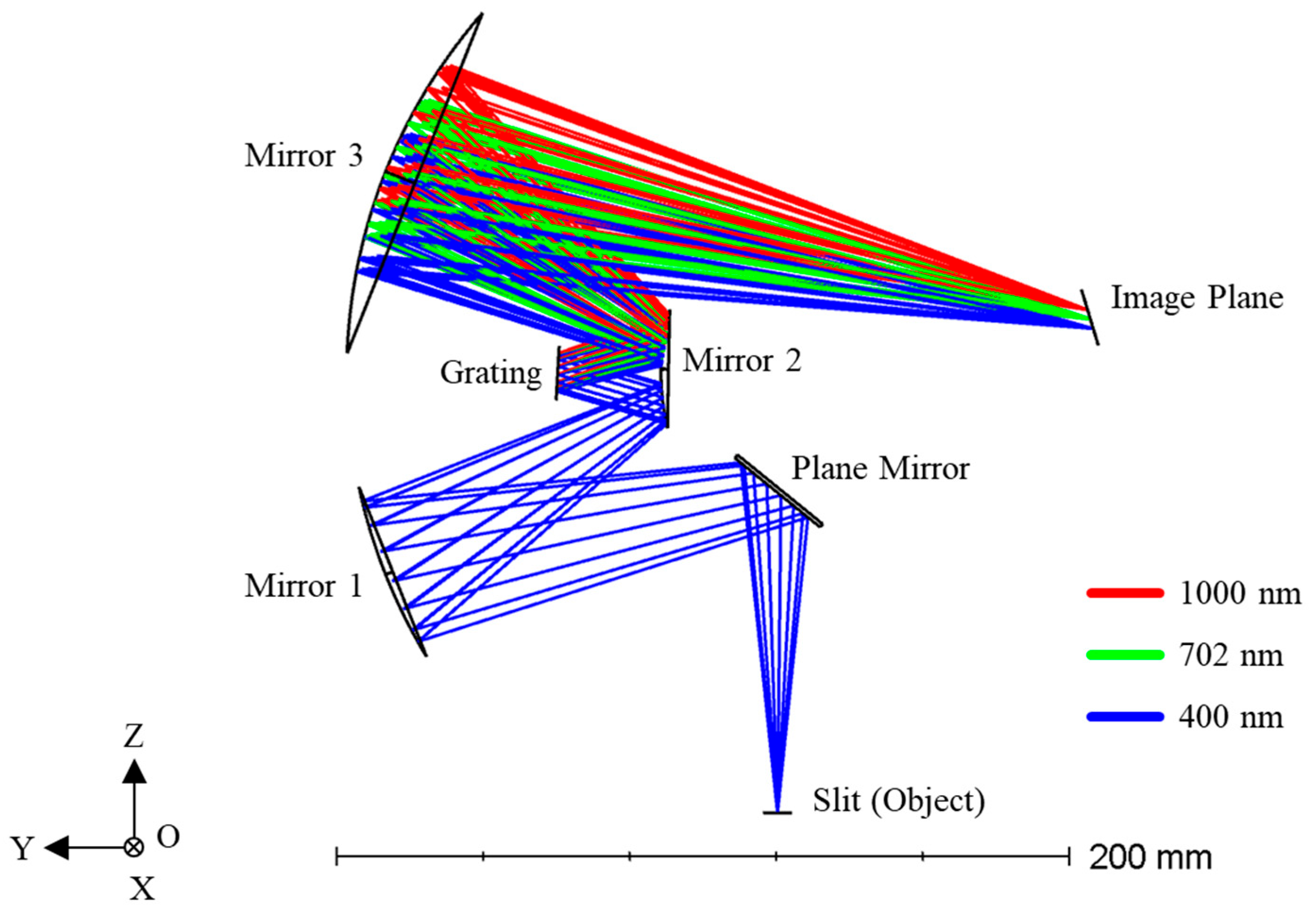

After designing the whole architecture of the HSI system, the hardware was then assembled using COTS components. The implementation of the prototype strictly adheres to the Schwarzschild optical configuration, with the entire process carried out on a precision optical platform. First, to verify the feasibility of the optical design, mechanical positioning was performed according to the spatial coordinates and orientations of the components determined by the optical design according to

Section 3.3. Key components, including the off-axis concave mirror (Mirror 1), convex mirror (Mirror 2), re-imaging concave mirror (Mirror 3), folding mirror, as well as the slit and image plane, were all precisely mounted onto standard threaded mounting holes on the optical platform using high-precision six-axis adjustment mounts (providing pitch, yaw, roll, and XYZ translation), as shown in

Figure 11a. This ensured that the relative positions and optical axis orientations of all elements conformed to the theoretical model, laying the foundation for optical alignment.

The alignment process was critical. A reverse alignment method was adopted, using the image plane as the reference. Initially, a He-Ne laser was used as an auxiliary alignment source, temporarily placed at the designed image plane position. The laser beam was projected in reverse order: first reflecting off Mirror 2 and the Grating, then finally being collimated by Mirror 1. By observing the profile and position of the output beam, rough adjustments of the pitch and yaw angles of each mirror were made to achieve preliminary closure of the optical path. Subsequently, a real broadband light source was introduced through the slit. At this stage, fine alignment entered a critical phase: Mirror 1 was finely adjusted to ensure the collimated beam incident onto the center of the grating in parallel; the grating’s groove orientation and incident angle were then meticulously tuned so that the diffracted light were in the desired angle; finally, the pose of Mirror 2 was finely adjusted to optimize the focusing of dispersed beams of various wavelengths until a clear, sharp, and minimally distorted spectral line was formed at the image plane. The entire process required iterative optimization, with real-time monitoring at the image plane using the CMOS camera. This ensured that the imaging performance of the entire system across the full field of view and all wavebands closely approached the design specifications.

Upon completion of the opto-mechanical alignment on an optical bench, all the geometric parameters were finalized. A black housing was designed to provide structural support for the optical components while minimizing the system’s overall volume and weight, thereby enhancing its adaptability for field operation. Each optical element was fixed by adhesive bonding, wherein the optical surfaces were mounted into corresponding mounting holes, so their relative positions relied heavily on the machining accuracy of the housing. Given the structural complexity of the housing, a hybrid manufacturing approach was adopted to reduce alignment difficulty in later stages: a preliminary structure was first produced via 3D printing of high hardness nylon, followed by CNC precision machining of the mounting surfaces to ensure that positional tolerances between critical interfaces met the values specified by the tolerance analysis. The fully assembled hyperspectral camera is shown in

Figure 11b.

3.2. Wavelength Coverage and Resolution Test

Following the hardware integration process, wavelength coverage and spectral resolution were experimentally analyzed in the dark room. The calibration system consists of three main components: a monochromator (Omni-λ300i, Zolix Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), a collimator (F550, Changfu Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), and the hyperspectral camera under test, all mounted on an optical bench to ensure mechanical and optical stability, as shown in

Figure 12a.

Wavelength calibration is a critical procedure in hyperspectral imaging. Its significance lies in establishing an accurate correspondence between each pixel of the camera’s detector and a specific wavelength, which directly determines the accuracy and reliability of the acquired spectral data. In the above setup, the monochromator generates quasi-monochromatic light with narrow spectral bandwidth and continuously tunable wavelength. The output beam is collimated to form a parallel light field, simulating an object at infinity and illuminating the entrance pupil of the camera under test. The hyperspectral camera receives this monochromatic light and forms an image of the slit on its image plane.

Figure 12b shows the spot distribution formed by 702 nm monochromatic light on the camera’s image plane. The spot exhibits an elongated shape with clear contours and good symmetry, which is directly related to the slit geometry and the effectiveness of astigmatism correction in the system. The high concentration of energy within the spot also reflects the excellent focusing capability of the system. This is further confirmed by the DN value curve along the central column of pixels for the 702 nm monochromatic light image, as shown in

Figure 12c. A distinct peak is observed around pixel number 470, corresponding to the maximum response of the detector to the 702 nm light.

By incrementally adjusting the output wavelength of the monochromator from 400 to 1000 nm, the digital number (DN) values along the central column of the detector were recorded and normalized for each wavelength increment. A total of 25 response curves at 25 nm intervals are plotted in

Figure 13a, comprehensively covering the target wavelength range. The results demonstrate that the hyperspectral camera exhibits effective photo response throughout the entire 400–1000 nm band, with each curve showing a distinct peak corresponding to the input monochromatic light. This confirms the system’s capability for accurate spectral detection across the visible and near-infrared regions.

To quantitatively evaluate the spectral resolution, the response to adjacent monochromatic light sources with a narrow wavelength interval of only 5 nm was further analyzed.

Figure 13b–d display the normalized response curves for three wavelength pairs: 400 nm and 405 nm, 702 nm and 707 nm, and 995 nm and 1000 nm, respectively. The results indicate that across different bands, i.e., short-wave (400/405 nm), mid-wave (702/707 nm), and long-wave (995/1000 nm), the response curves for all wavelength pairs are effectively separated, forming two distinct and resolvable peaks. This result demonstrates that the camera can clearly distinguish adjacent monochromatic lights with a wavelength difference of only 5 nm. According to the Rayleigh criterion, two adjacent wavelengths are considered resolved if their peak responses are clearly distinguishable and the valley between them is lower than 80% of the peak intensities. The curves for all wavelength pairs shown in the figure exceed this criterion. In conclusion, these test results proved that the developed hyperspectral camera prototype achieves a spectral coverage of 400–1000 nm with a resolution better than 5 nm across the entire operating band.

3.3. Acquisition of Hyperspectral Image

Following the completion of hardware integration and software development for the hyperspectral imaging system, an imaging experiment was conducted to evaluate the camera’s functionality and performance. The experiment was conducted on the 6th floor of Tower D in No. 9 Dengzhuang South Road, Haidian District, Beijing, at 10:00 a.m. under stable illumination conditions. The camera, equipped with a 25 mm focal length lens, was set to an exposure time of 5 ms and operated at a frame rate of 150 fps. It was mounted on a precision rotational stage to perform push-broom scanning of a natural scene containing various features such as trees, buildings, and the sky, while simultaneously saving data in real time.

Figure 14 presents the outdoor scene imaging test results of the developed hyperspectral camera prototype.

Figure 14a shows an RGB image recorded by a Nikon P950 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with hyperspectral camera scanning, providing an intuitive visualization of the test scene: green trees, gray-white building facades, and a bright blue sky. The experimental setup, including the hyperspectral camera, the rotational stage, and the control computer, is shown in

Figure 14b.

The core analysis focuses on the monochromatic band images extracted from the acquired hyperspectral data cube at central wavelengths spaced 100 nm apart (i.e., 400 nm, 500 nm, 600 nm, 700 nm, 800 nm, 900 nm) presented in

Figure 14c–h. These monochromatic images clearly reveal significant brightness variations in different ground objects due to their unique spectral reflectance characteristics.

The spectral behavior of vegetation is a key focus of analysis. In the 400 nm (blue) and 500 nm (green) bands, leaves exhibit low reflectance due to strong chlorophyll absorption in the blue and red regions for photosynthesis, thus appearing dark gray in

Figure 14c,d. At 600 nm (orange-red), which is near the end of the chlorophyll absorption valley (red absorption), reflectance slightly increases but remains relatively low. From 700 nm onward, a dramatic change occurs. The spongy mesophyll structure inside the leaves leads to a pronounced “near-infrared red-edge effect,” causing a sharp increase in reflectance within the 700–900 nm range. In the

Figure 14f 800 nm and

Figure 14h 900 nm images, the leaves appear exceptionally bright, even dazzling white, due to their very high reflectance, contrasting sharply with their appearance in other bands. This is the most distinctive spectral signature of healthy vegetation.

The spectral reflectance curve of building materials (e.g., concrete, paint) is generally flat and smooth, approximating those of a Lambertian (diffuse) reflector, exhibiting near-isotropic scattering across the measured wavelength range. This means their reflectance ability changes little across different wavelengths. Thus, in the monochromatic images from 400 nm to 900 nm, the brightness of the buildings remains relatively stable without the dramatic variations seen in vegetation. They appear as medium gray across all bands, with reflectance levels intermediate between highly reflective vegetation (in the near-infrared) and some low-reflectance dark features.

The brightness of the sky is primarily governed by atmospheric scattering mechanisms. In shorter wavelengths such as 400 nm and 500 nm, Rayleigh scattering (which is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the wavelength) is extremely significant. A large amount of blue and violet light is scattered by atmospheric molecules into the camera, making the sky appear very bright in

Figure 14c,d. As the wavelength increases, Rayleigh scattering diminishes rapidly. At 600 nm and longer wavelengths, molecular scattering decreases substantially, atmospheric transmittance increases, and scattered light intensity weakens. As a result, the brightness of the sky continuously decreases in

Figure 14e–h, appearing increasingly dark. This indicates that the camera successfully captured the spectral characteristics determined by atmospheric physics.

This experiment also successfully acquired and analyzed the three-dimensional data cube generated by the push-broom hyperspectral imaging system. The rich spectral information contained within provides critical evidence for accurately distinguishing and identifying different ground objects. As shown in

Figure 15a, the data cube clearly displays typical urban features, including building facades, the sky, two types of trees, and green dust nets at a distant construction site.

Analysis of the normalized spectral curves extracted in the upper plots in

Figure 15b indicates that the spectral profiles of the building facade and the sky exhibit high similarity across the entire VNIR range (400–1000 nm). Their reflectance trends with respect to wavelength are nearly identical, further confirming that the spectral property of the building façade is similar to a Lambertian (diffuse) reflector.

The spectral curves in the lower part of

Figure 15b fully demonstrate the core advantage of hyperspectral technology. First, although Tree-1 (

Platanus) and Tree-2 (

Ginkgo biloba) both belong to vegetation and appear similar in RGB true-color imagery, their detailed spectral curves show quantifiable differences in visible-light absorption characteristics and near-infrared plateau reflectance intensity. These discrepancies may be attributed to factors such as tree species, health conditions, or canopy structure, illustrating the potential of hyperspectral data to identify intra-class spectral variability (same object, different spectra) or inter-class spectral similarity (different objects, similar spectra).

More notably, the spectral curves of the green artificial dustproof net and natural trees reveal a fundamental distinction: although their reflectance values are similar in the green band (~550 nm) due to the use of green dye mimicking chlorophyll reflectance, a dramatic difference emerges in the critical near-infrared region (>700 nm). Natural vegetation exhibits very high reflectance owing to the “near-infrared red-edge effect” caused by the internal leaf structure, whereas the artificial dust net completely lacks this bio-optical characteristic, maintaining very low reflectance. This strong contrast in the NIR region serves as a reliable spectral fingerprint for distinguishing artificial green materials from natural vegetation.

In summary, the experimental results systematically verify that the developed hyperspectral camera can effectively capture the unique spectral features of ground objects. The data cube it produces not only facilitates land cover classification but also enables fine material discrimination beyond the capability of human vision, holding significant application value in fields such as precision agriculture, environmental monitoring, and urban remote sensing.

3.4. Comparison with Previous Works

Having detailed the design and validation of the proposed COTS hyperspectral camera, it is crucial to benchmark these results against the state of the art. The comparative analysis that follows examines fundamental specifications such as spectral coverage, number of bands, and F-number, under relatively similar cost, highlighting the balance of performance and size realized by this work, as shown in

Table 7.

Compared to previous works, this paper achieves a notable spectral coverage of 400–1000 nm VNIR range, surpassing the range of previous systems which typically covering approximately 400–800 nm. The spectral resolution of 5 nm, while slightly lower than some counterparts, results from a deliberate design choice utilizing spherical off-axis mirrors, which present challenges in high-precision alignment but offer significant advantages in cost and manufacturability. A key feature is the high number of spectral bands (930), which enhances spectral sampling density. The potential signal reduction per band inherent to such a high channel count is effectively mitigated by the high throughput of the all-reflective optical system. Furthermore, practical data volume can be optimized via pixel binning, tailoring the output to application needs without compromising utility. Critically, a performance metric not captured in the table is the integration time, directly governing frame rate. For instance, under comparable good illumination conditions (e.g., 10:30 a.m.), the system in Ref. [

33] requires a 50 ms integration time, limiting its frame rate to below 20 fps. In stark contrast, the system presented here operates with a markedly shorter 5 ms integration time under similar conditions (10:00 a.m.), enabling a high frame rate of 150 fps. This substantial increase in scanning efficiency is paramount for field deployments, especially in UAV-based push-broom applications, where it directly translates to enhanced operational throughput.