Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Combined with Unscented Kalman Filter

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research Status and Limitations

1.3. Research Content and Research Contributions

2. Establishment and Validation of the Vehicle Dynamics Model

2.1. Derivation of Dynamic Equations by Degrees of Freedom

2.1.1. Body Longitudinal Motion

2.1.2. Body Lateral Motion

2.1.3. Body Yaw Motion

2.1.4. Body Roll Motion

2.1.5. Wheel Rotational Motion

2.2. Tire Force Model and Axle Load Transfer Calculation

2.2.1. Calculation of Axle Load Transfer

2.2.2. Tire Longitudinal Force Model

2.2.3. Tire Lateral Force Model

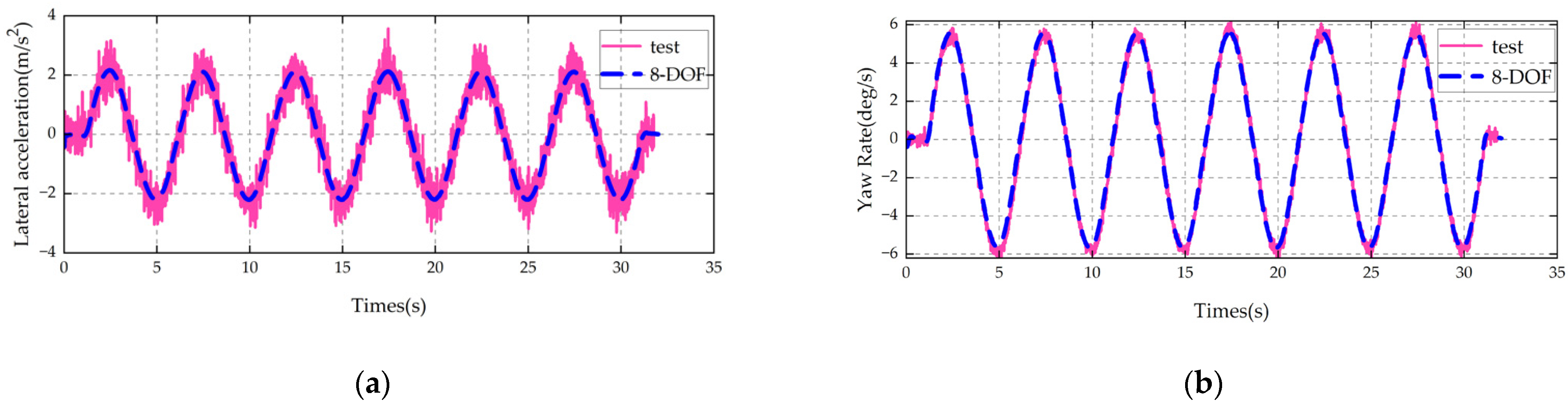

2.3. Validation of Model Effectiveness

3. Refined Design of UKF Based on the 8-DOF Model

3.1. Extended Definition of State and Observation Vectors

3.1.1. State Vector

3.1.2. Observation Vector

- : yaw rate, core sensor: MEMS Gyroscope (IMU), observation function ;

- : longitudinal acceleration, core sensor: MEMS Accelerometer (IMU), observation function

- : lateral acceleration, core sensor: MEMS Accelerometer (IMU), observation function

- : roll angle, core sensor: IMU (Accelerometer + Gyroscope), observation function

- : four-wheel speed, core sensor: wheel speed sensor, observation function , , , .

3.2. Optimization of Core Parameters for High-Dimensional UKF

3.2.1. Initialization Parameters

3.2.2. Calculation of 8-Dimensional Sigma Point Parameters and Weights

3.3. Implementation of UKF Discretization

3.3.1. Prediction Step (8-Dimensional State Transition)

- 1.

- Sigma Point Generation:

- 2.

- RK4 Discretized State Transition:

- 3.

- Calculation of Predicted State and Covariance:

3.3.2. Update Step

- 1.

- Observation Sigma Point Generation:

- 2.

- Calculation of Observation Covariance and Cross-Covariance:

- 3.

- Kalman Gain and State Update:

3.4. Lightweight Design of UKF

- Longitudinal Wheel Speed Subsystem: State variables , covariance submatrix (5 × 5), and optimization objective: estimation accuracy of longitudinal velocity and wheel speeds;

- Lateral–Roll Subsystem: State variables , covariance submatrix (3 × 3), and optimization objective: estimation accuracy of sideslip angle and roll angle;

- Tire Force Correlation Subsystem: The coupling weights between subsystems are dynamically adjusted based on the tire force saturation degree . In the non-saturation region, the focus is on optimization; in the saturation region, the focus is on robustness.

4. DRL Noise Adjustment Framework Adapted to the 8-DOF Model

4.1. State Space Expansion

4.2. Action Space Expansion

4.3. Reward Function Optimization

4.3.1. Immediate Reward

- (Sideslip Angle Accuracy Reward): , (core estimation target, in the non-saturation region, in the saturation region);

- (Roll Angle Accuracy Reward): , (roll angle affects axle load and lateral force, with a fixed weight);

- (Wheel Speed Accuracy Reward): , (wheel speed affects slip ratio, with a fixed weight);

- (Filter Stability Reward): , ( is the trace of the 8-dimensional covariance matrix, with a fixed weight);

- (Action Smoothness Reward): , (to avoid severe fluctuations of the 16-dimensional action, with a fixed weight);

- (Tire Force Adaptation Reward): (for , it is 0.5 in the non-saturation region and 0.8 in the saturation region), ( in the non-saturation region, in the saturation region, to enhance robustness in the saturation region).

4.3.2. Terminal Reward

4.4. PPO Network Structure and Training Optimization

4.4.1. Network Lightweight Design

4.4.2. Training Strategy Adjustment

5. Robustness and Stability Analysis of the Estimation Method

5.1. Robustness Analysis

5.1.1. Robustness to Model Parameter Perturbations

5.1.2. Subsubsection

5.1.3. Robustness to Sudden Changes in Working Conditions

- adjustment: , , increase significantly, dominated by model errors in lateral velocity (tire force saturation), coupling errors in roll angle (enhanced axle load transfer), and slip ratio errors in rear wheel speed ;

- adjustment: increases because lateral acceleration sensors are affected by vehicle roll, causing temporary increases in measurement noise, which requires reducing their observation weight.

5.2. Stability Analysis

5.2.1. Analysis of Filter Convergence

5.2.2. Analysis of State Estimation Boundedness

5.2.3. Analysis of DRL Training Stability

5.3. Summary

6. Experimental Verification and Result Analysis

6.1. Virtual Simulation Verification

6.1.1. Simulation Platform and Test Setup

6.1.2. Simulation Results of Slalom Maneuver

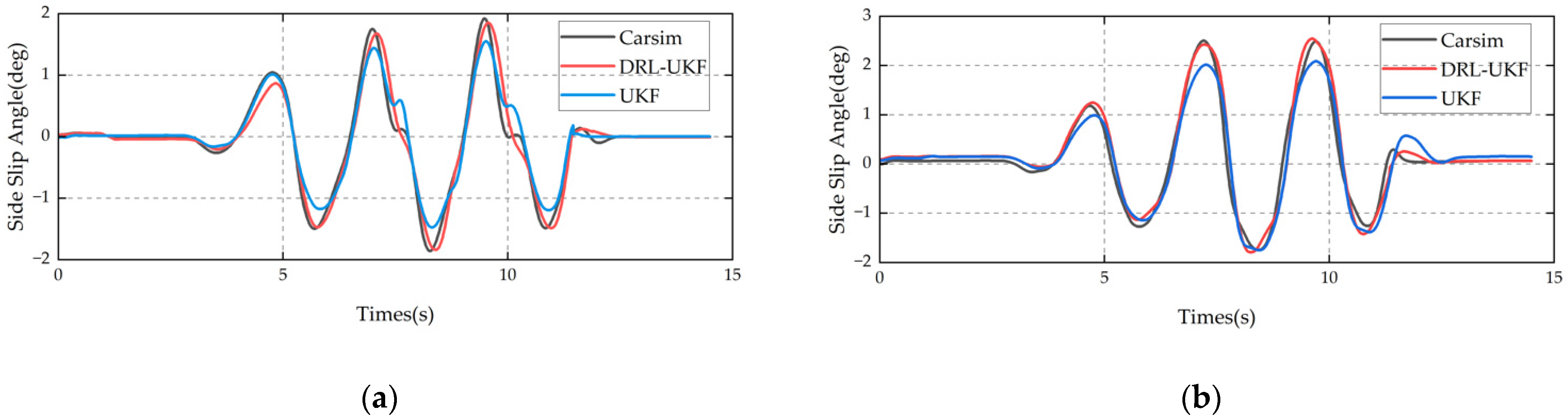

6.1.3. Simulation Results of Double-Lane-Change Maneuver

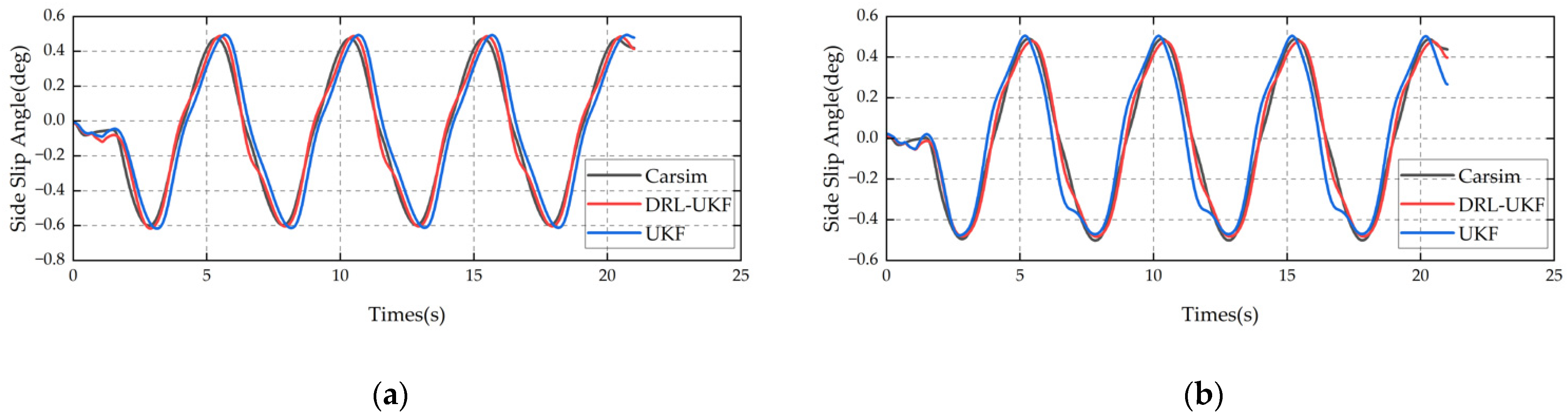

6.1.4. Simulation Results of Sinusoidal Maneuver

6.1.5. Summary of Simulation Results

6.2. Real-Vehicle Test Verification

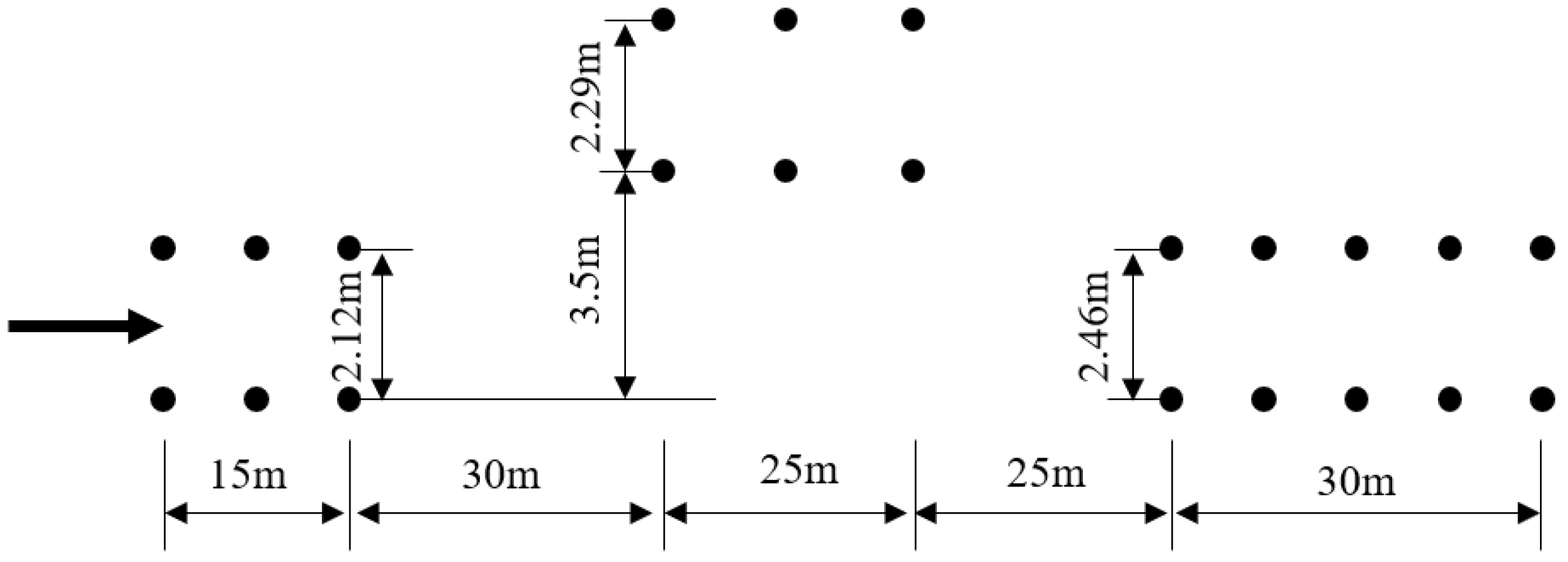

6.2.1. Test Platform and Vehicle Parameters

6.2.2. Real Test Results of Double-Lane-Change Maneuver

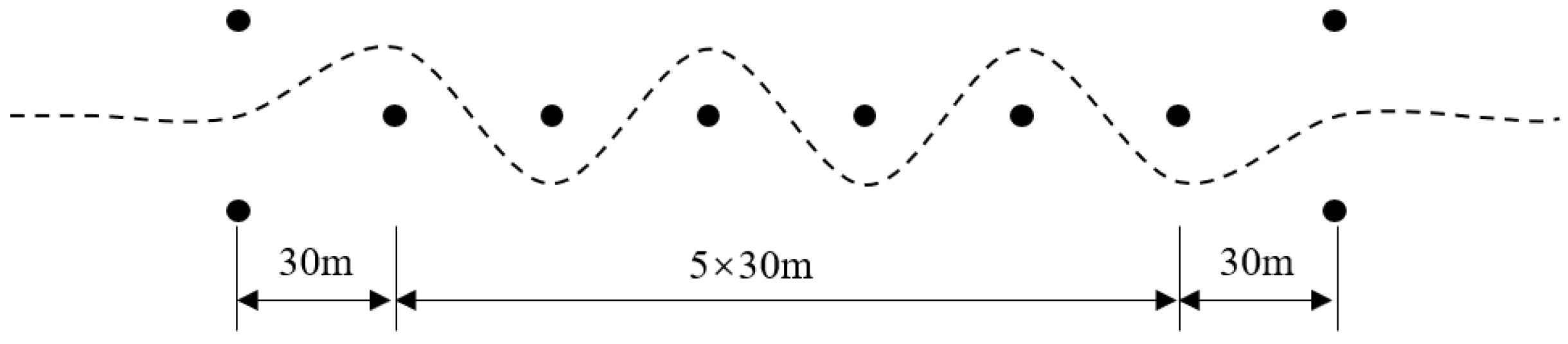

6.2.3. Real Test Results of Slalom Maneuver

6.2.4. Summary of Test Verification Results

6.3. Test Conclusions

7. Conclusions

- An estimation architecture with deep integration of UKF and DRL is proposed. A “dual closed-loop collaborative” estimation framework is constructed, which is based on an 8-degree-of-freedom vehicle dynamics model and uses DRL to dynamically optimize noise parameters. This framework realizes the organic integration of physical models and data-driven methods and effectively overcomes the problem of degraded estimation performance of traditional methods under model perturbations and noise interference.

- A DRL-based noise adaptive mechanism adapted to high-dimensional UKF is designed. The state space and action space are expanded, the tire force saturation is introduced as the basis for operating condition division, the structure of the reward function is optimized, and the PPO algorithm is used to train the policy network. This realizes the dynamic adjustment of the process noise covariance Q and the observation noise covariance R, and improves the adaptive capability of the filter.

- The effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method are verified through virtual simulations and real-vehicle tests. Under various typical operating conditions, such as slalom, double-lane change, and sinusoidal steering, the sideslip angle estimation accuracy of the proposed DRL-UKF method is significantly better than that of the traditional UKF. Both the evaluation error and Root Mean Square Error are greatly improved, and stable estimation is still maintained under extreme scenarios such as low-adhesion roads and high-speed steering.

- A new idea is provided for the estimation of key vehicle state parameters. This study not only realizes the deep coupling of model-driven and data-driven approaches at the method level, but also provides a promotable technical path for real-time state perception and control system design in fields such as autonomous driving and vehicle active safety.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Villano, E.; Lenzo, B.; Sakhnevych, A. Cross-combined UKF for vehicle sideslip angle estimation with a modified Dugoff tire model: Design and experimental results. Meccanica 2021, 56, 2653–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufano, F.; Lui, D.G.; Battistini, S.; Brancati, R.; Lenzo, B.; Santini, S. Vehicle Sideslip Angle estimation under critical road conditions via nonlinear Kalman filter-based state-dependent Interacting Multiple Model approach. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 146, 105901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Hu, J.; Yan, Y.; Shen, L.; He, Z.; Yin, G. An integrated approach for vehicle state estimation under non-ideal conditions using adaptive strong tracking maximum correntropy criterion EKF. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 14604–14616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lin, X.; Hou, Y.; Ren, J.; Wang, M. Application of an Improved Adaptive Unscented Kalman Filter in Vehicle Driving State Parameter Estimation. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 2025, 39, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidfeld, H.; Schünemann, M.; Kasper, R. Experimental validation of a GPS-aided model-based UKF vehicle state estimator. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics (ICM), Ilmenau, Germany, 18–20 March 2019; Volume 1, pp. 537–543. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; He, D.; Mo, S. A hybrid physics-data driven approach for vehicle dynamics state estimation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 225, 112249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, L.; Shan, Z.; Ma, F. Vehicle state and bias estimation based on unscented kalman filter with vehicle hybrid kinematics and dynamics models. Automot. Innov. 2023, 6, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, V.R.; Kalkkuhl, J.; Raisch, J.; Scholte, W.J.; Nijmeijer, H.; Seel, T. Multi-modal sensor fusion for highly accurate vehicle motion state estimation. Control Eng. Pract. 2020, 100, 104409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Choi, S.B.; Hyun, D.; Lee, J. Integrated observer approach using in-vehicle sensors and GPS for vehicle state estimation. Mechatronics 2018, 50, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, X. RBCKF-based vehicle state estimation by adaptive weighted fusion strategy considering composite-state tire model. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; He, H.; Chen, X.; Gao, J. Learning-based vehicle state estimation using Gaussian process regression combined with extended Kalman filter. J. Frankl. Inst. 2024, 361, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Feng, J.; Wan, W.; Song, B. A novel maximum correntropy adaptive extended Kalman filter for vehicle state estimation under non-Gaussian noise. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 34, 025114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, H.; Li, Y. Vehicle state estimation based on sage–Husa adaptive unscented Kalman filtering. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atheupe, G.P.; Gurjar, B.; Kongue, G.; Tapus, A.; Monsuez, B. A comprehensive benchmarking study of various non-linear state estimators for vehicle sideslip angle estimation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 2–5 June 2024; pp. 1939–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, X.; Tian, Y.; Ghani, H.A.; Wang, H.; Ali, S.A. Sampled-data neural network observer for motion state estimation of full driving automation vehicle. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 2726–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseur, C.; Van Aalst, S.; Desmet, W. Robust vehicle state and tire force estimation: Highlights on effects of road angles and sensor performance. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Nagoya, Japan, 11–17 July 2021; pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.J.; Zhou, X.L.; Ran, M.P. Estimation of sideslip angle based on the combination of dynamic and kinematic methods. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2025, 26, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Song, Z. Vehicle State Estimation by Integrating the Recursive Least Squares Method with a Variable Forgetting Factor with an Adaptive Iterative Extended Kalman Filter. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Fan, X.; Chen, X.; Yi, J.; He, S. UKF estimation method of centroid slip angle for vehicle stability control. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2023, 21, 2259–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Son, H.; Wang, Y.; Nam, K.; Choi, S. Vehicle side-slip angle estimation of ground vehicles based on a lateral acceleration compensation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 180433–180443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidfeld, H.; Schünemann, M.; Kasper, R. UKF-based State and tire slip estimation for a 4WD electric vehicle. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2020, 58, 1479–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshawi, A.; De Pinto, S.; Stano, P.; van Aalst, S.; Praet, K.; Boulay, E.; Ivone, D.; Gruber, P.; Sorniotti, A. An adaptive unscented kalman filter for the estimation of the vehicle velocity components, slip angles, and slip ratios in extreme driving manoeuvres. Sensors 2024, 24, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, F.; Liu, C. Vehicle state estimation based on extended Kalman filter and radial basis function neural networks. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2022, 18, 15501329221102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, B.; Du, H.; Zhang, B. Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy-based Kalman filter observer for vehicle side-slip angle estimation and lateral stability control. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Symposium on Autonomous Systems (ISAS), Shanghai, China, 29–31 May 2019; pp. 352–357. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, H.; Hu, B.; Lv, C. Robust estimation of vehicle dynamic state using a novel second-order fault-tolerant extended kalman filter. SAE Int. J. Veh. Dyn. Stab. NVH 2023, 7, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cui, D. Estimation algorithm for vehicle state estimation using ant lion optimization algorithm. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 16878132221085839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, F.; Su, L.; Lin, B.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y. State parameter fusion estimation for intelligent vehicles based on IMM-MCCKF. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, P.; Xie, Z.; Li, Z.; Huan, H. Road Adhesion Coefficient Estimation Based on Vehicle-Road Coordination and Deep Learning. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2023, 3633058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Cheng, S.; Li, L.; Zhong, Z.; Mu, H. A robust unscented M-estimation-based filter for vehicle state estimation with unknown input. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 6119–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Yue, M.; Shangguan, J.; Guo, L.; Zhao, J. Integrated control method for path tracking and lateral stability of distributed drive electric vehicles with extended Kalman filter–based tire cornering stiffness estimation. J. Vib. Control 2024, 30, 2582–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qian, L.; Chen, J.; Xuan, L.; Chen, X. Multi-innovation adaptive UKF with robust estimation using QS decomposition for vehicle state estimation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2025, 09544070241313090. [Google Scholar]

- Ziaukas, Z.; Busch, A.; Wielitzka, M. Estimation of vehicle side-slip angle at varying road friction coefficients using a recurrent artificial neural network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications (CCTA), San Diego, CA, USA, 9–11 August 2021; pp. 986–991. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Moussa, H.; Bakhti, M. Nonlinear tyre model-based sliding mode observer for vehicle state estimation. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2024, 12, 2944–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggaber, J.; Pölzleitner, D.; Brembeck, J. AI-Based Vehicle State Estimation Using Multi-Sensor Perception and Real-World Data. Sensors 2025, 25, 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Cai, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; Chen, L. Vehicle state estimation combining physics-informed neural network and unscented Kalman filtering on manifolds. Sensors 2023, 23, 6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.X.; Liu, X.H.; Chen, W.; Zhou, C.; Cao, B.-W. Improving handling stability performance of four-wheel steering vehicle based on the H2/H∞ robust control. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammari, O.; El Majdoub, K.; Giri, F.; Baz, R. Nonlinear control of a half electric vehicle including an inverter, an in-wheel BLDC motor and Pacejka’s tire model. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2024, 12, 3366–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, T.; Stepan, G.; Takacs, D.; Chen, N. Vehicle shimmy modeling with Pacejka’s magic formula and the delayed tire model. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 15, 031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, K.G.; Amir, M.; Warn, G.P. A Scaled Spherical Simplex Filter (S3F) with a decreased n+ 2 sigma points set size and equivalent 2n+ 1 Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) accuracy. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 163, 107433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nino-Ruiz, E.D.; Diaz-Rodriguez, J. A 4D-EnKF Method via a Modified Cholesky Decomposition and Line Search Optimization for Non-Linear Data Assimilation. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, R.; Dheer, D.K. Vehicle state estimation using a maximum likelihood based robust adaptive extended Kalman filter considering unknown white Gaussian process and measurement noise signal. Eng. Res. Express 2023, 5, 025066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Feng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, B. A robust hierarchical estimation scheme for vehicle state based on maximum correntropy square-root cubature Kalman filter. Entropy 2023, 25, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseur, C.; van Aalst, S.; Desmet, W. Vehicle state and tire force estimation: Performance analysis of pre and post sensor additions. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19 October–13 November 2020; pp. 1615–1620. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, M.; Dalai, S.; Trslic, P.; Riordan, J.; Dooly, G. LSAF-LSTM-Based Self-Adaptive Multi-Sensor Fusion for Robust UAV State Estimation in Challenging Environments. Machines 2025, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Z. A deep reinforcement learning-based intelligent fault diagnosis framework for rolling bearings under imbalanced datasets. Control Eng. Pract. 2024, 145, 105845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3888-1:2018; Passenger Cars: Test Track for a Severe Lane-Change Manoeuver—Part 1: Double-Lane Change. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- GB/T 6323-2014; Controllability and Stability Test Procedure for Automobile. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

| Method Category | Specific Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Measurement Instrument Methods | Inertial Sensor Scheme | Directly measures lateral acceleration with a simple calculation | Long-term accuracy degradation due to noise accumulation and large integration error |

| GPS Combination Scheme | Dynamic correction; stable output under neutral steering conditions | Sensitive to sampling efficiency and environmental occlusion; limited by signals | |

| Traditional Estimation Algorithms | Direct Integration Method | Small calculation load and good real-time performance | Large long-term estimation deviation caused by error accumulation |

| Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) | Linearizes nonlinear systems with simple calculation; stable performance under small sideslip angle conditions; and accuracy meets basic control needs | Only applicable to linear/small sideslip angle conditions; large error in nonlinear processing | |

| Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) | Avoids linearization error via unscented transformation; high accuracy in nonlinear processing (superior to EKF); and optimal performance in snake-like maneuvering on high-adhesion roads | Fixed noise covariance; poor adaptability to time-varying parameters; and high computational complexity | |

| Sliding Mode Observer | Stronger adaptability to load transfer and road condition changes; high robustness | Accuracy is limited by switching function design; prone to chattering | |

| Luenberger Observer | Stronger adaptability to load transfer and road condition changes; estimation results of second-order or generalized versions are closer to true values | Complex design; requires accurate model parameters | |

| Data-Driven Technologies | Neural Networks, Fuzzy Logic, etc. | No need for accurate models; improves accuracy and reliability through fusion estimators | Requires massive labeled data; lack of physical constraints easily leads to unphysical results |

| Piecewise Affine Estimation Method | Considers the nonlinearity of wheel lateral force saturation; high feasibility verified by experiments | Relies on piecewise model design; limited generalization ability | |

| Fusion of Physical Model and Data-Driven Methods (e.g., Fuzzy Logic + UKF, ANFIS + UKF) | Integrates advantages; enables effective parameter observation; and improves robustness | The fusion strategy is simple, but estimation jumps are prone to occur during the working condition transition phase | |

| Improved Unscented Kalman Filter | Adaptive Singular Value Decomposition UKF | Real-time correction of noise covariance matrix; reduced error on complex roads; and strong anti-noise capability | Increased computational time; affected real-time performance |

| Fuzzy Control + UKF | Enables adaptive adjustment of measurement noise; improved accuracy under double-lane-change conditions | Complex design; requires adjustment of fuzzy rules | |

| Fault-Tolerant Noise Estimator + UKF | Realizes joint estimation of side-slip angle and tire cornering stiffness | High computational complexity; requires multi-sensor fusion | |

| Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) | DRL-Optimized Weights (e.g., CNN-LSTM) | Addresses insufficient generalization of traditional neural networks; controlled error growth under off-training-set conditions | Poor real-time performance; requires massive computing resources |

| DRL as Model Error Compensator | Learns error patterns based on dynamic model output; reduced estimation deviation in double-lane-change tests | Relies on basic models; complex compensator training | |

| DRL + Fuzzy Sliding Mode Observer | Optimizes saturation function parameters; suppresses chattering; accelerates convergence speed; and reduces response lag in tire nonlinear regions | Poor real-time performance; complex parameter adjustment | |

| DRL + EKF | Dynamically adjusts filter gain; improves estimation stability under sudden sensor signal changes | Insufficient fusion depth; limited real-time performance | |

| Fusion Framework Trend | UKF + DRL (Proposed Scheme) | Optimizes noise parameters via DRL; physical model constrains estimation boundaries; and achieves high accuracy and robustness across all conditions | Still in the research stage; difficult to balance real-time performance and generalization |

| Variables | Physical Meaning | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal velocity of the vehicle’s center of mass | m/s | |

| Lateral velocity of the vehicle’s center of mass | m/s | |

| Vehicle yaw rate | rad/s | |

| Vehicle roll angle | rad | |

| Vehicle roll angular velocity | rad/s | |

| Total vehicle mass | kg | |

| Vehicle moment of inertia about the z-axis | kg·m2 | |

| Vehicle moment of inertia about the x-axis | kg·m2 | |

| / | Distance from the center of mass to the front/rear axle | m |

| Track width | m | |

| Estimated value of wheel lateral force | N | |

| Rotational angular velocity of the front-left wheel | rad/s | |

| Rotational angular velocity of the front-right wheel | rad/s | |

| Rotational angular velocity of the rear-left wheel | rad/s | |

| Rotational angular velocity of the rear-right wheel | rad/s | |

| Wheel longitudinal force () | N | |

| Wheel lateral force () | N | |

| Wheel vertical load () | N | |

| Wheel driving torque (, 4WD distribution) | N·m | |

| Wheel braking torque () | N·m | |

| Wheel rolling radius | m | |

| Tire force saturation degree () | - |

| Parameter Name | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle mass m | 1499.6 | kg |

| Wheelbase L | 2700 | mm |

| The distance from the center to the front axis lf | 1267 | mm |

| The distance from the center to the rear axis lr | 1433 | mm |

| The height from the center to the ground hg | 551 | mm |

| Rolling radius of tire r | 320.2 | mm |

| Front axle wheel base Bf | 1530 | mm |

| Rear axle wheel base Br | 1530 | mm |

| Roll moment of inertia Ix | 483.4 | kg⋅m2 |

| Pitch moment of inertia Iy | 1528.6 | kg⋅m2 |

| Moment of inertia of the yaw Iz | 1685.2 | kg⋅m2 |

| Item | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Mass | 1499.6 | kg |

| Wheelbase | 2700 | mm |

| Distance from the center of mass to the front/rear axle | 1267/1433 | mm |

| Height of the center of mass | 551 | mm |

| Tire radius | 320.2 | mm |

| Front/rear track width | 1530/1530 | mm |

| Moment of inertia (Izz) | 1685.2 | kg⋅m2 |

| Project | Traditional UKF Method (Deg) | DRL-UKF Method (Deg) | Percentage of Performance Improvement (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slalom Test Adhesion Coefficient 0.2 | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.115 | 0.11 | 4.35 |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.173 | 0.169 | 2.31 | |

| Slalom Test Adhesion Coefficient 0.8 | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.171 | 0.132 | 22.81 |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.225 | 0.19 | 15.56 | |

| Double-Lane-Change Test Adhesion Coefficient 0.2 | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.182 | 0.154 | 15.38 |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.249 | 0.215 | 13.65 | |

| Double-Lane-Change Test Adhesion Coefficient 0.8 | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.108 | 0.064 | 40.74 |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.169 | 0.1 | 40.83 | |

| Sinusoidal Steering Test Adhesion Coefficient 0.2 | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.088 | 0.034 | 61.36 |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.098 | 0.041 | 58.16 | |

| Sinusoidal Steering Test Adhesion Coefficient 0.8 | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.071 | 0.03 | 57.75 |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.091 | 0.036 | 60.44 | |

| Parameter Name | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle mass m | 1499.6 | kg |

| Wheelbase L | 2700 | mm |

| The distance from the center to the front axis lf | 1267 | mm |

| The distance from the center to the rear axis lr | 1433 | mm |

| The height from the center to the ground hg | 551 | mm |

| Rolling radius of tire r | 320.2 | mm |

| Front axle wheel base Bf | 1530 | mm |

| Rear axle wheel base Br | 1530 | mm |

| Roll moment of inertia Ix | 483.4 | kg⋅m2 |

| Pitch moment of inertia Iy | 1528.6 | kg⋅m2 |

| Moment of inertia of the yaw Iz | 1685.2 | kg⋅m2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, L.; Wang, W.; Li, P.; Zhu, Y. Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Combined with Unscented Kalman Filter. Sensors 2025, 25, 7489. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247489

Wu L, Wang W, Li P, Zhu Y. Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Combined with Unscented Kalman Filter. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7489. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247489

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Liguang, Wei Wang, Penghui Li, and Yueying Zhu. 2025. "Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Combined with Unscented Kalman Filter" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7489. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247489

APA StyleWu, L., Wang, W., Li, P., & Zhu, Y. (2025). Vehicle Sideslip Angle Estimation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Combined with Unscented Kalman Filter. Sensors, 25(24), 7489. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247489