Adaptive 3D Augmentation in StyleGAN2-ADA for High-Fidelity Lung Nodule Synthesis from Limited CT Volumes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- StyleGAN2-ADA PyTorch adaptation for 3D data with all augmentation methods of the base implementation adapted to work with 3D data.

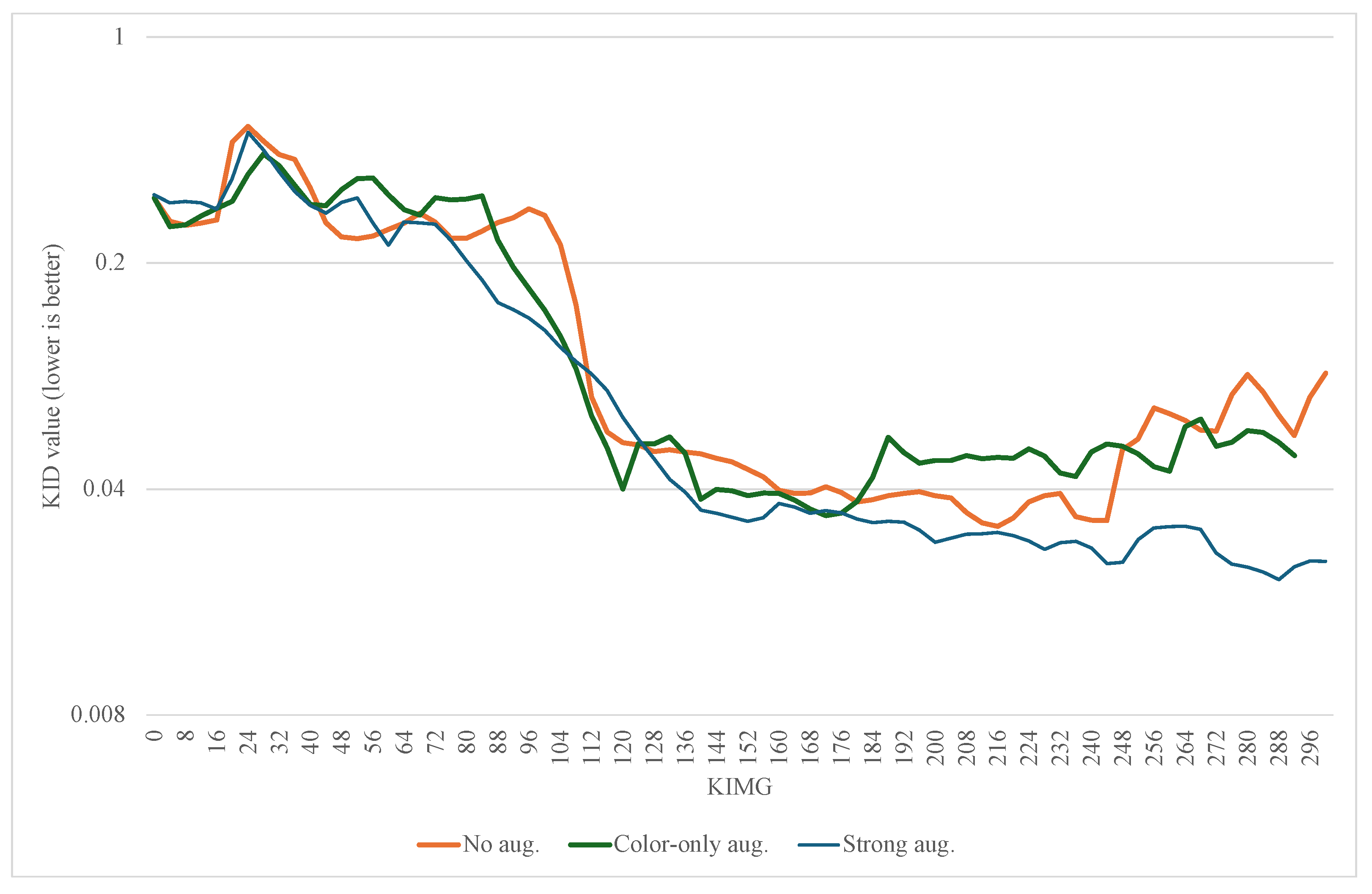

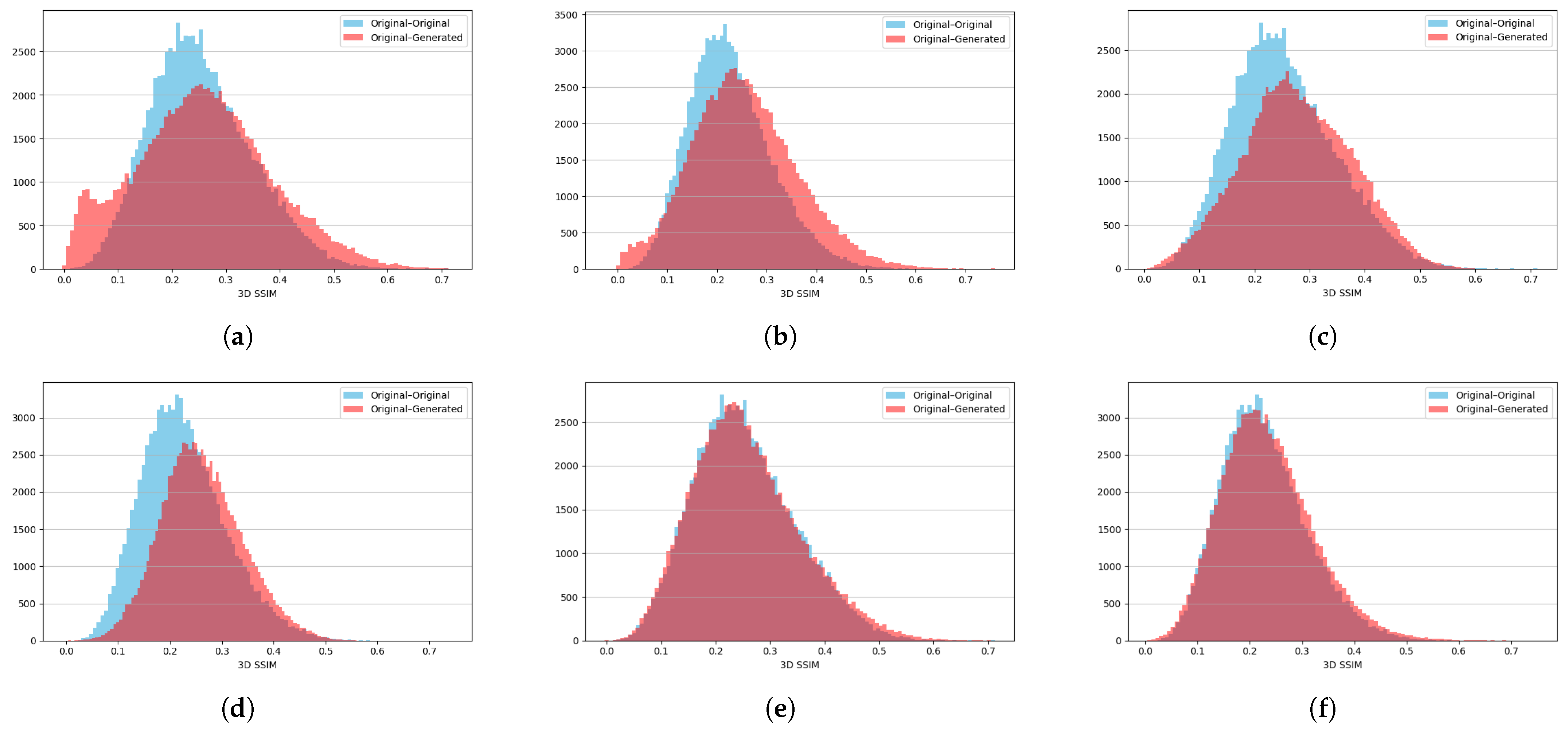

- An empirical evaluation of the adapted network across varying augmentation settings (full augmentation set, color-only augmentations, and no augmentations at all) for the balanced dataset containing 590 3D images of CT scans of lung nodules. The metrics used in evaluation are Kernel Inception Distance and 3D Structural Similarity Index Measure calculated on the generated and original objects.

- A comparative analysis using established image-synthesis metrics between three different augmentation scenarios.

Related Works

2. Materials and Methods

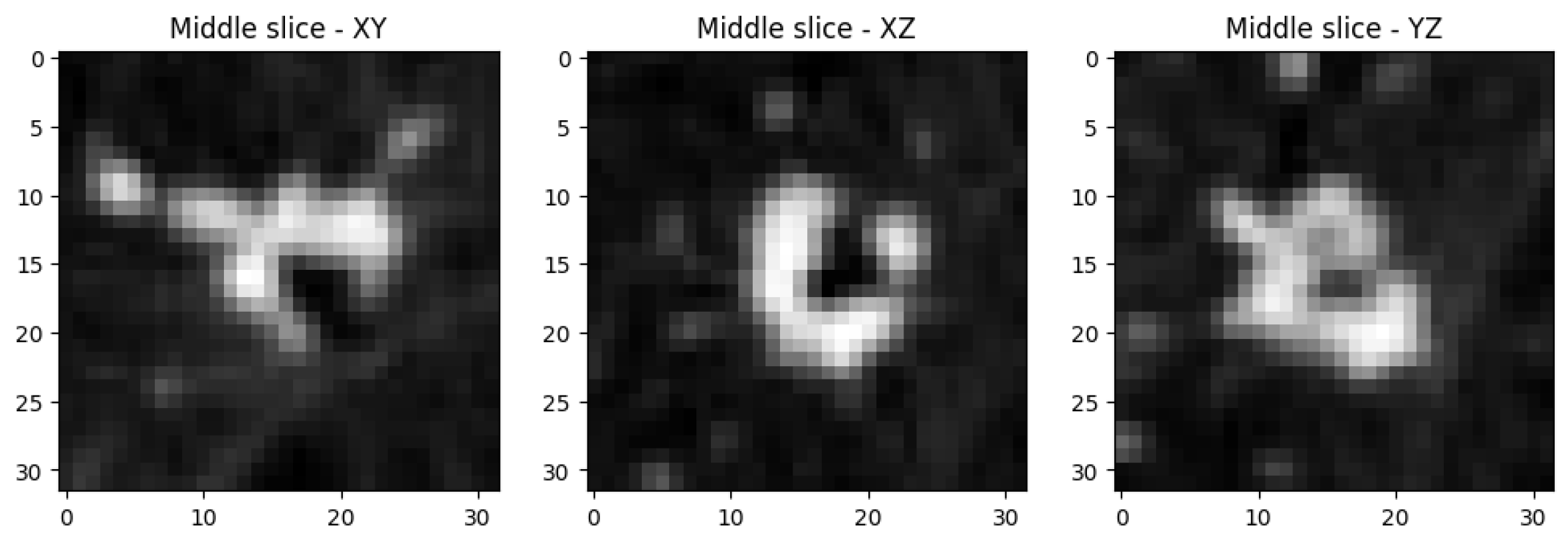

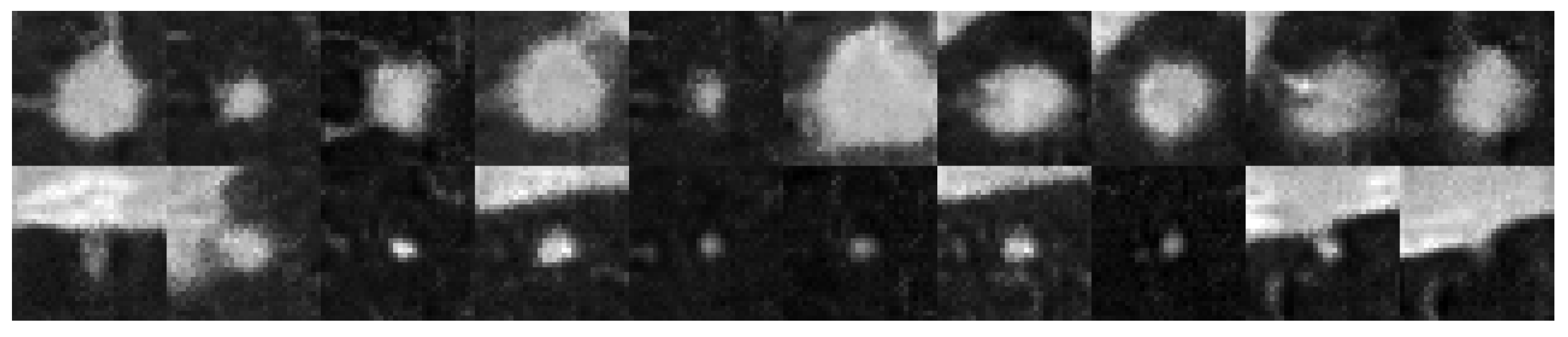

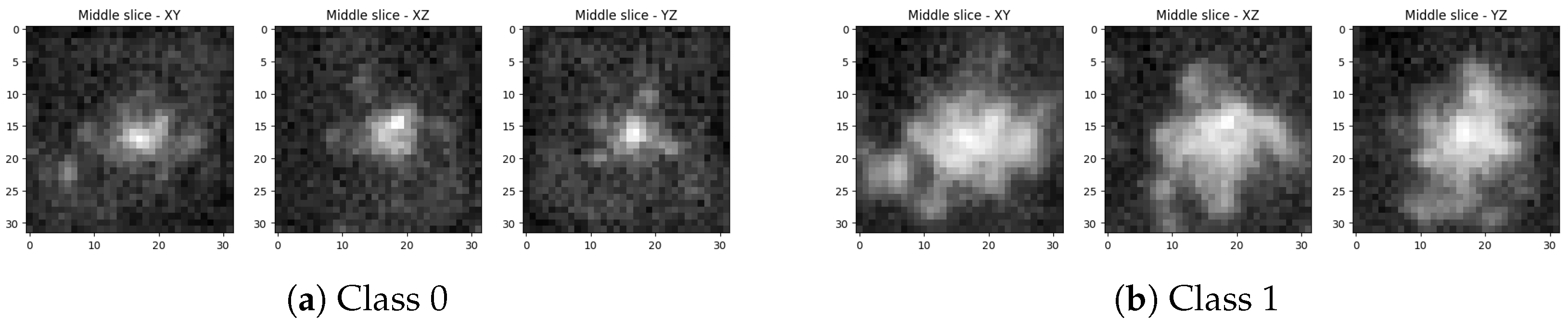

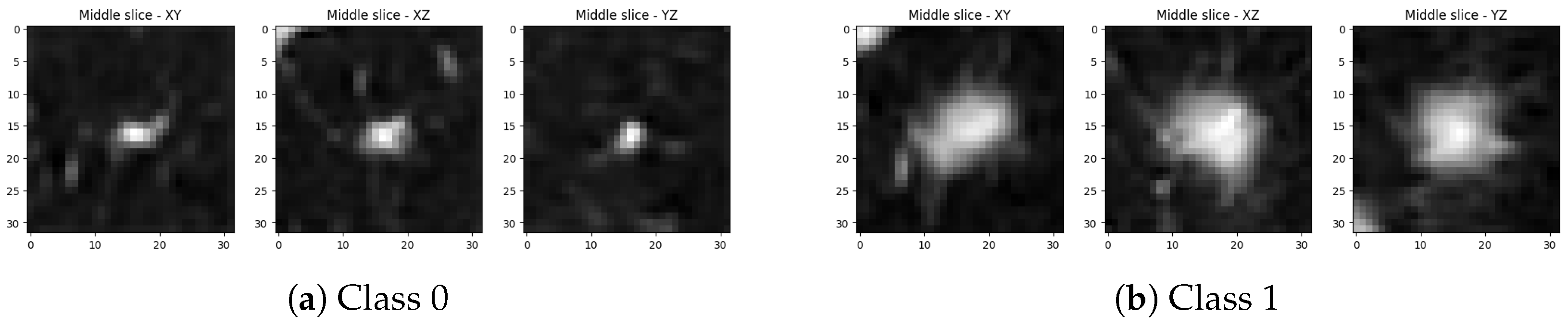

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Networks

2.3. Augmentations

- Pixel-level editing—horizontal flipping along the sagittal axis, random rotations in the axial plane, and integer translations along the sagittal, coronal, and axial axes.

- Geometric transformations—isotropic scaling, arbitrary rotations, anisotropic scaling, and fractional translations.

- Color transformations—adjustments to brightness, saturation, and contrast; luma inversion; and hue rotation.

- Image-space filtering—filtering by amplification or suppression of the frequency content in different bands.

- Image corruptions—cutouts of parts of the images and application of Gaussian noise.

2.4. Training

2.5. Quality Evaluation and Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Findings

3.2. Discussion

3.3. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, W.; Leem, S.; See, K.B.; Wong, J.K.; Zhang, S.; Fang, R. A Comprehensive Survey of Foundation Models in Medicine. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfner, F.J.; Patel, J.B.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Gerstner, E.R.; Bridge, C.P. A review of deep learning for brain tumor analysis in MRI. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.P.; Wang, L.; Gupta, S.; Goli, H.; Padmanabhan, P.; Gulyás, B. 3D deep learning on medical images: A review. Sensors 2020, 20, 5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27 (NeurIPS 2014); Ghahramani, Z., Welling, M., Cortes, C., Lawrence, N.D., Weinberger, K.Q., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2014; pp. 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Aittala, M.; Hellsten, J.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Training Generative Adversarial Networks with Limited Data. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020); Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M.-F., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Akbar, M.U.; Larsson, M.; Blystad, I.; Eklund, A. Brain tumor segmentation using synthetic MR images—A comparison of GANs and diffusion models. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekala, R.R.; Pahde, F.; Baur, S.; Chandrashekar, S.; Diep, M.; Wenzel, M.; Wisotzky, E.L.; Yolcu, G.Ü.; Lapuschkin, S.; Ma, J.; et al. Synthetic Generation of Dermatoscopic Images with GAN and Closed-Form Factorization. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2024 Workshops; Del Bue, A., Canton, C., Pont-Tuset, J., Tommasi, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 368–384. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Xu, S.; He, P.; Wu, S.; Luo, X.; Deng, Y.; Huang, H. VSG-GAN: A high-fidelity image synthesis method with semantic manipulation in retinal fundus image. Biophys. J. 2024, 123, 2815–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedoruk, O.; Klimaszewski, K.; Ogonowski, A.; Kruk, M. Additional look into GAN-based augmentation for deep learning COVID-19 image classification. Mach. Graph. Vis. 2023, 32, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahani, M.; El Ouaazizi, A.; Avram, R.; Maalmi, K. Enhancing chest X-ray diagnosis with text-to-image generation: A data augmentation case study. Displays 2024, 83, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ma, D.; Zhao, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, H.; Tang, J.; Li, C. Semantics guided disentangled GAN for chest X-ray image rib segmentation. In Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV 2024), Urumqi, China, 18–20 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golhar, M.V.; Bobrow, T.L.; Ngamruengphong, S.; Durr, N.J. GAN inversion for data augmentation to improve colonoscopy lesion classification. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 3864–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Court, L.E.; Wang, H.; Pan, T.; Phan, J.; Wang, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, J. SC-GAN: Structure-completion generative adversarial network for synthetic CT generation from MR images with truncated anatomy. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2024, 113, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Booven, D.J.; Chen, C.-B.; Malpani, S.; Mirzabeigi, Y.; Mohammadi, M.; Wang, Y.; Kryvenko, O.N.; Punnen, S.; Arora, H. Synthetic Genitourinary Image Synthesis via Generative Adversarial Networks: Enhancing Artificial Intelligence Diagnostic Precision. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Marinescu, R.; Dalca, A.V.; Bonkhoff, A.K.; Bretzner, M.; Rost, N.S.; Golland, P. 3D-StyleGAN: A style-based generative adversarial network for generative modeling of three-dimensional medical images. In Deep Generative Models, and Data Augmentation, Labelling, and Imperfections (DGM4MICCAI 2021, DALI 2021), MICCAI Workshops; Engelhardt, S., Oksuz, I., Zhu, D., Yuan, Y., Mukhopadhyay, A., Heller, N., Huang, S.X., Nguyen, H., Sznitman, R., Xue, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 13003, pp. 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. 3D-StyleGAN2-ADA: Unofficial PyTorch Implementation with Partial 3D Augmentations. GitHub Repository. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/sh4174/3d-stylegan2-ada (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- StyleGAN2-ADA—Official PyTorch Implementation. Available online: https://github.com/NVlabs/stylegan2-ada-pytorch (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Angermann, C.; Bereiter-Payr, J.; Stock, K.; Degenhart, G.; Haltmeier, M. Three-Dimensional Bone-Image Synthesis with Generative Adversarial Networks. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Hang, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, S.; Hong, Y. Super-resolution of 3D medical images by generative adversarial networks with long and short-term memory and attention. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellmer, S.; Aydogan, D.B.; Roine, T.; Cacciola, A.; Picht, T.; Fekonja, L.S. Diffusion MRI GAN synthesizing fibre orientation distribution data using generative adversarial networks. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, O.U.; Hilbert, A.; Koch, A.; Lohrke, F.; Rieger, J.; Tanioka, S.; Frey, D. Generative modeling of the Circle of Willis using 3D-StyleGAN. NeuroImage 2024, 304, 120936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazerouni, A.; Aghdam, E.K.; Heidari, M.; Azad, R.; Fayyaz, M.; Hacihaliloglu, I.; Merhof, D. Diffusion models in medical imaging: A comprehensive survey. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 88, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolleb, J.; Bieder, F.; Sandkühler, R.; Cattin, P.C. Diffusion Models for Medical Anomaly Detection. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2022; Wang, L., Dou, Q., Fletcher, P.T., Speidel, S., Li, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13438, pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, T.; Li, B.; Yang, A.; Yan, Y.; Jiao, C. DiffGAN: An adversarial diffusion model with local transformer for MRI reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2024, 109, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Ji, W.; Fu, H.; Xu, M.; Jin, Y.; Xu, Y. MedSegDiff-V2: Diffusion-based medical image segmentation with transformer. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-24), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; pp. 6030–6038. [Google Scholar]

- Armato, S.G., III; McLennan, G.; Bidaut, L.; McNitt-Gray, M.F.; Meyer, C.R.; Reeves, A.P.; Zhao, B.; Aberle, D.R.; Henschke, C.I.; Hoffman, E.A.; et al. The Lung Image Database Consortium (LIDC) and Image Database Resource Initiative (IDRI): A completed reference database of lung nodules on CT scans. Med. Phys. 2011, 38, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Shi, R.; Wei, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Ke, B.; Pfister, H.; Ni, B. MedMNIST v2—A Large-Scale Lightweight Benchmark for 2D and 3D Biomedical Image Classification. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Shi, R.; Ni, B. MedMNIST classification decathlon: A lightweight AutoML benchmark for medical image analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Nice, France, 13–16 April 2021; pp. 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bińkowski, M.; Sutherland, D.J.; Arbel, M.; Gretton, A. Demystifying MMD GANs. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2018), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, K.; Wang, Z. 3D-SSIM for video quality assessment. In Proceedings of the 19th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Orlando, FL, USA, 30 September–3 October 2012; pp. 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image Quality Assessment: From Error Visibility to Structural Similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebaili, A.; Lapuyade-Lahorgue, J.; Ruan, S. Deep learning approaches for data augmentation in medical imaging: A review. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16 × 16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=YicbFdNTTy (accessed on 11 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fedoruk, O.; Klimaszewski, K.; Kruk, M. Adaptive 3D Augmentation in StyleGAN2-ADA for High-Fidelity Lung Nodule Synthesis from Limited CT Volumes. Sensors 2025, 25, 7404. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247404

Fedoruk O, Klimaszewski K, Kruk M. Adaptive 3D Augmentation in StyleGAN2-ADA for High-Fidelity Lung Nodule Synthesis from Limited CT Volumes. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7404. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247404

Chicago/Turabian StyleFedoruk, Oleksandr, Konrad Klimaszewski, and Michał Kruk. 2025. "Adaptive 3D Augmentation in StyleGAN2-ADA for High-Fidelity Lung Nodule Synthesis from Limited CT Volumes" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7404. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247404

APA StyleFedoruk, O., Klimaszewski, K., & Kruk, M. (2025). Adaptive 3D Augmentation in StyleGAN2-ADA for High-Fidelity Lung Nodule Synthesis from Limited CT Volumes. Sensors, 25(24), 7404. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247404