Towards In-Vehicle Non-Contact Estimation of EDA-Based Arousal with LiDAR

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology—Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Experimental Protocol

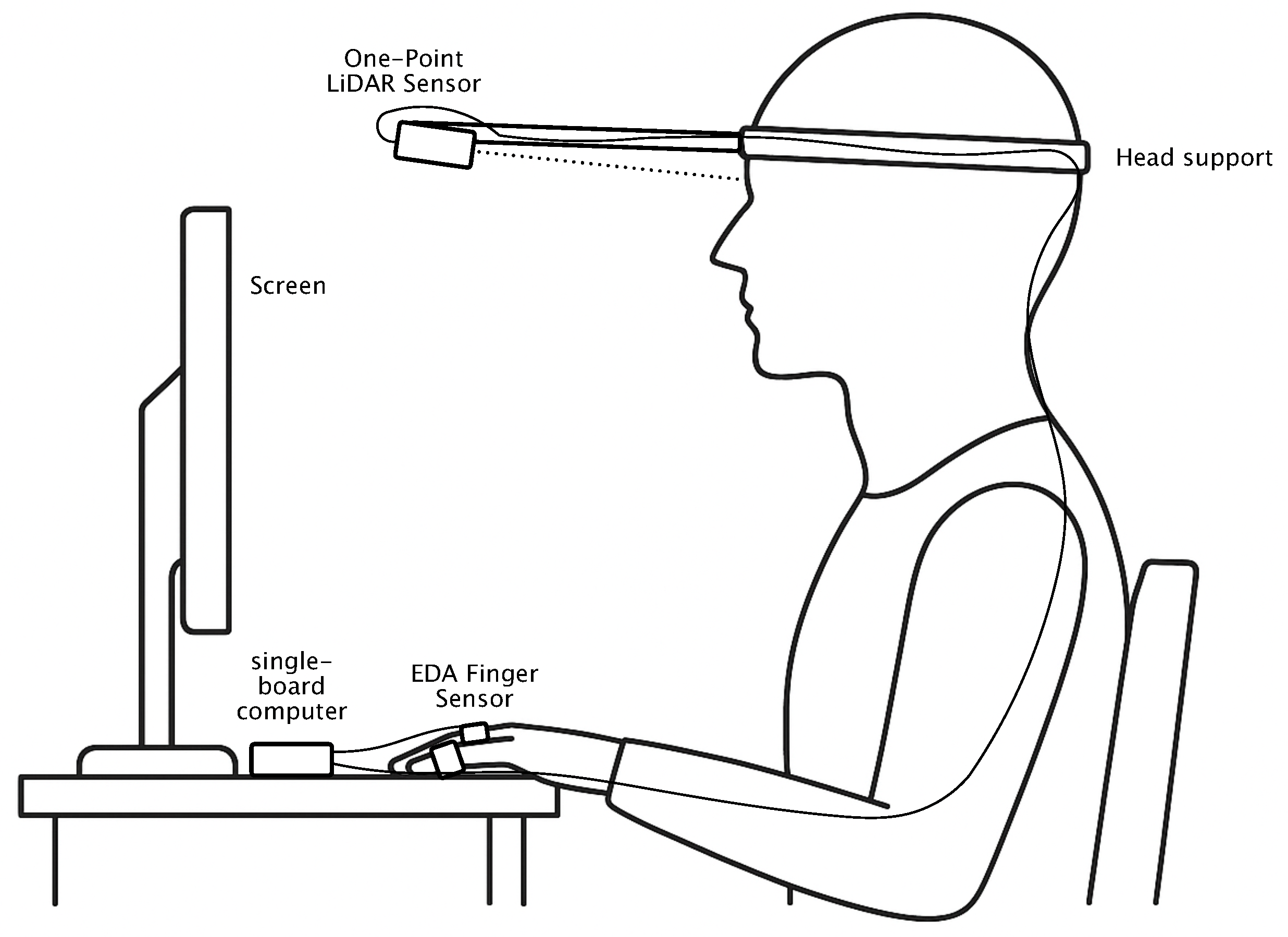

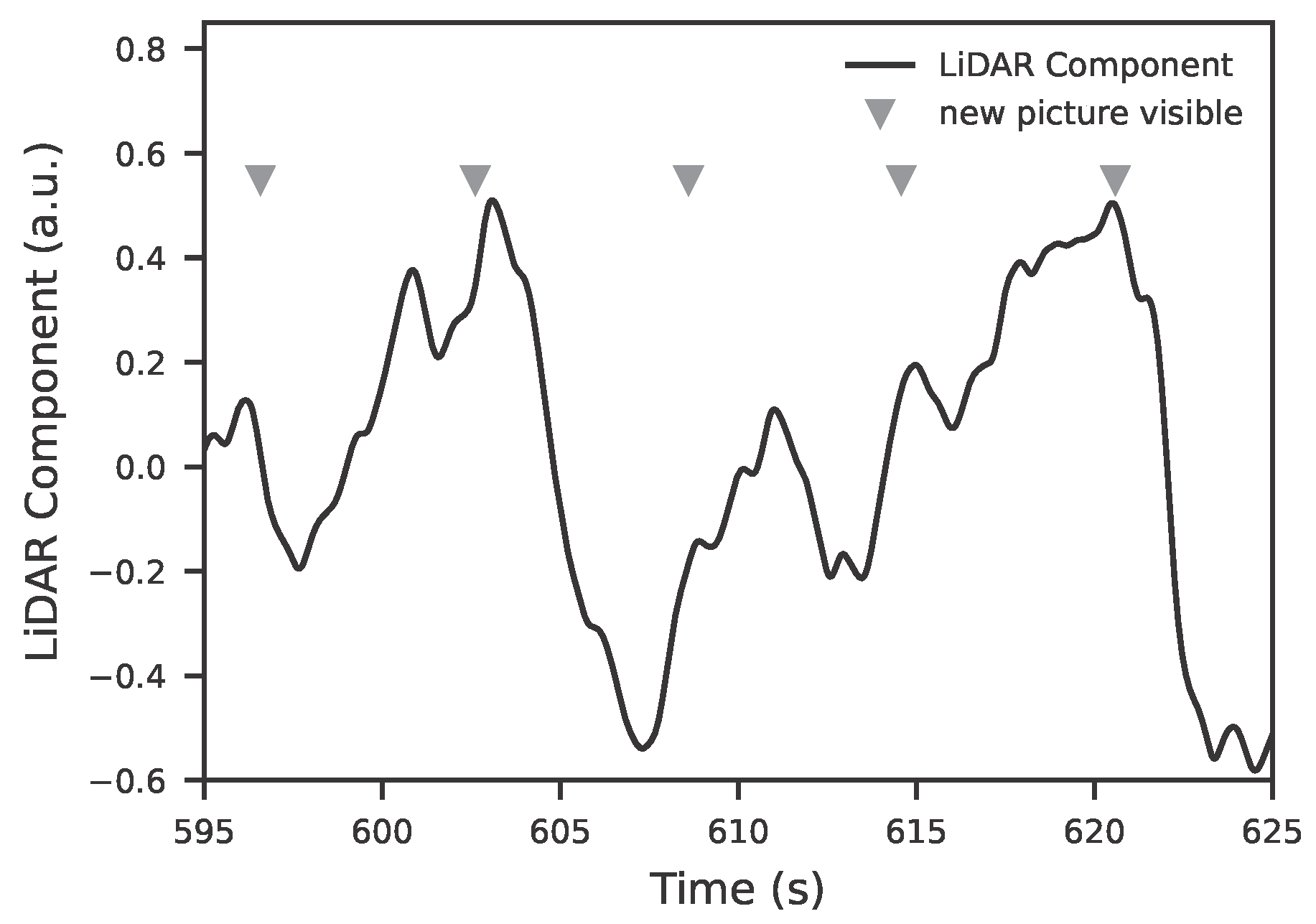

2.1.1. Sensor Technology: LiDAR Sensor

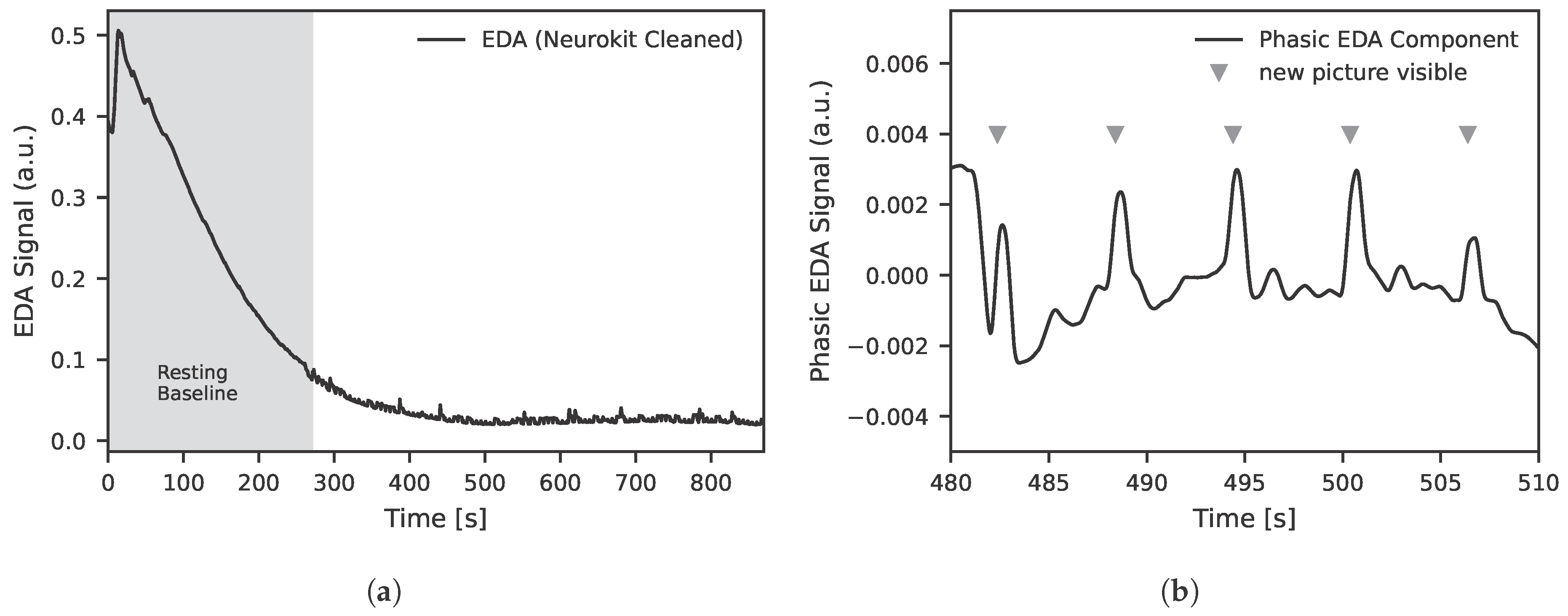

2.1.2. Sensor Technology: EDA Sensor

2.1.3. Design of Stimulus Presentation

2.1.4. System Control and Data Acquisition

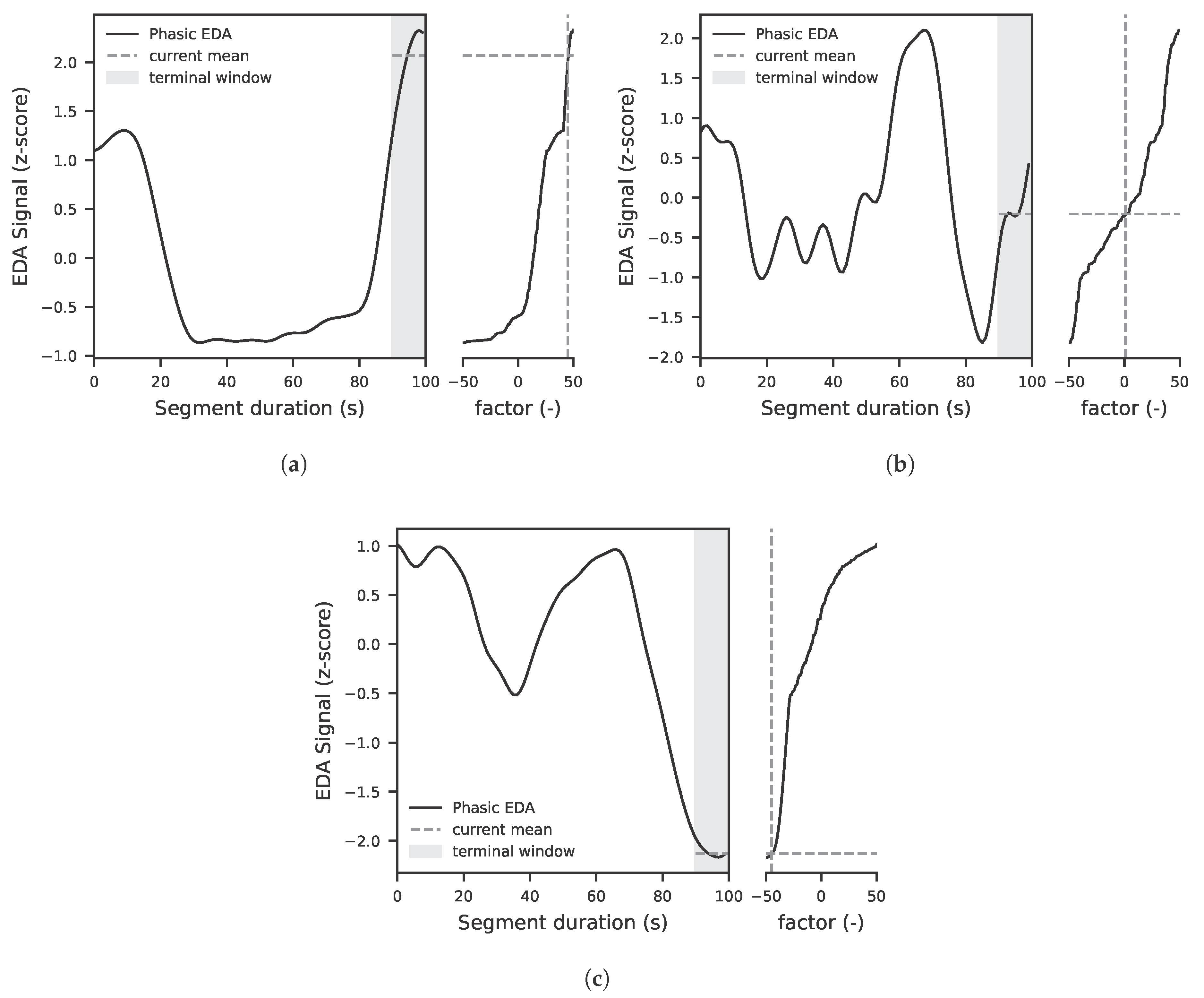

2.2. Data Processing and Feature Extraction

2.3. Modeling Approach

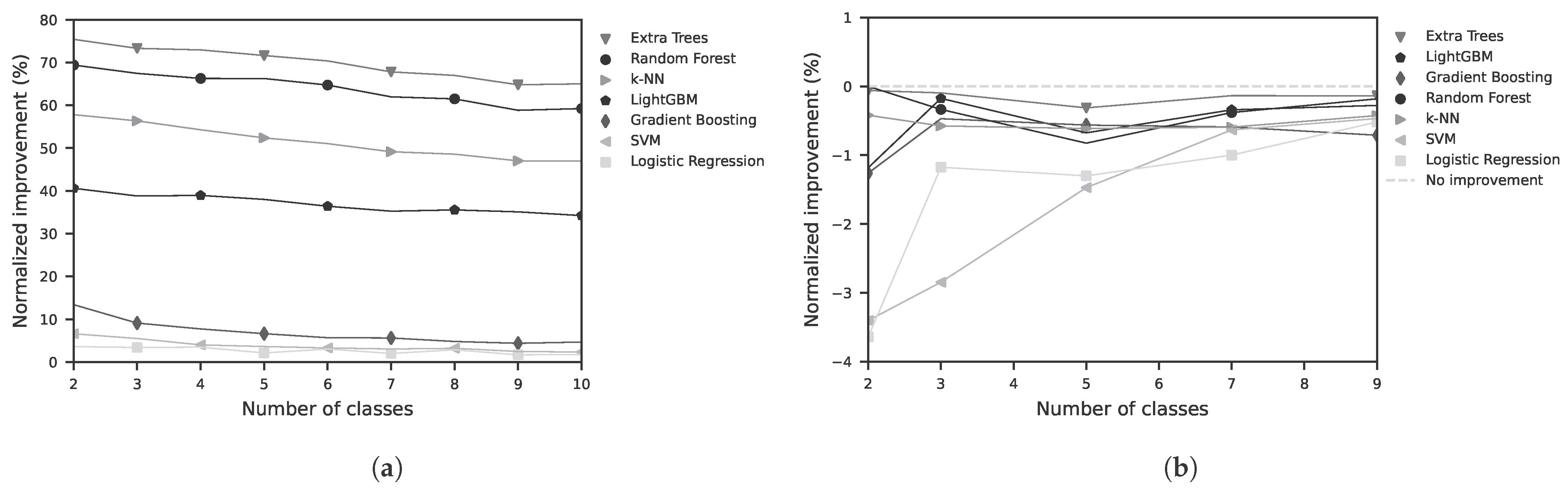

2.3.1. Feature-Based Classification Approach

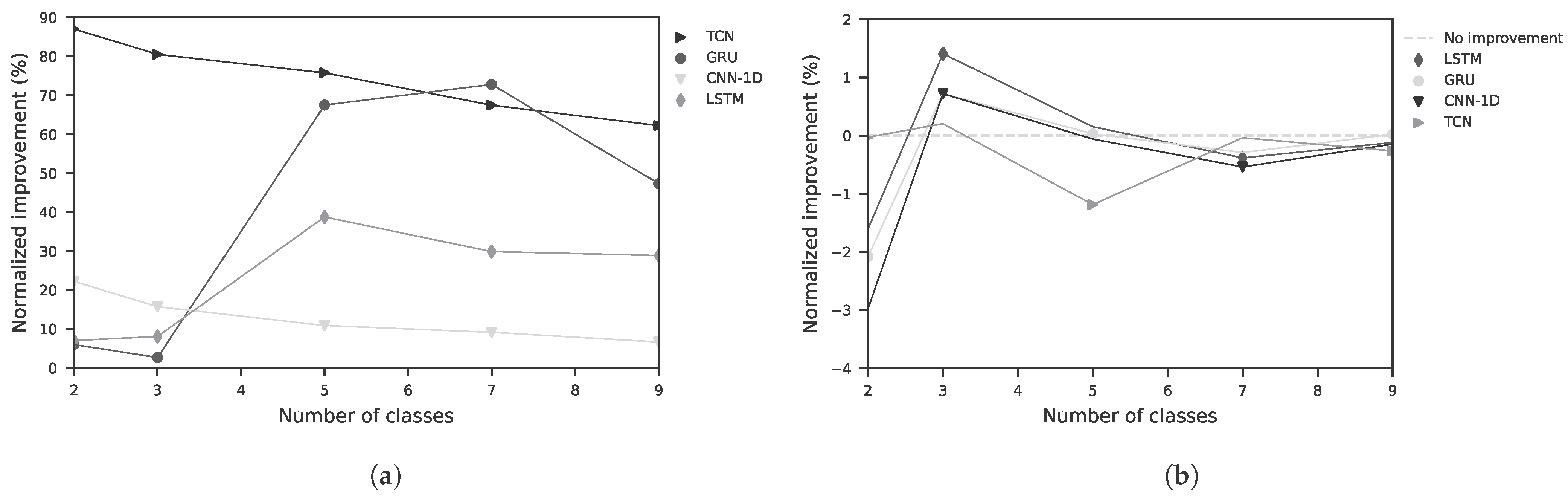

2.3.2. Sequence-Based Classification Approach

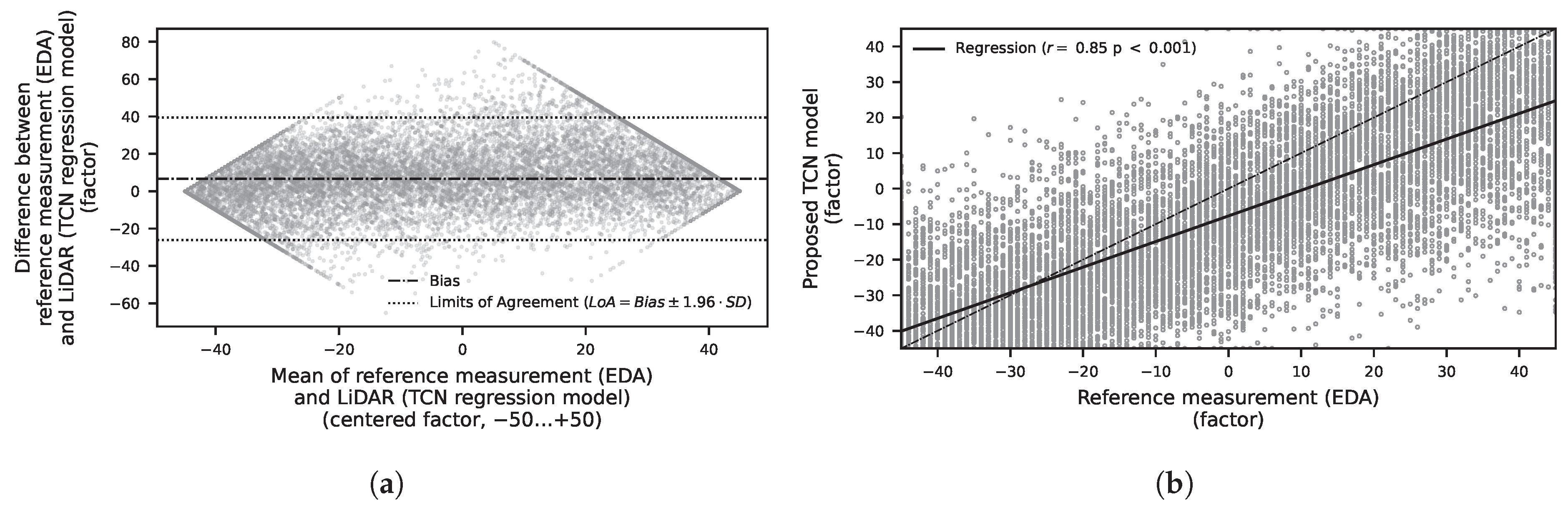

2.3.3. Feature-Based Regression Approach

2.3.4. Sequence-Based Regression Approach

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BA | balanced accuracy |

| CNN | convolutional neural network |

| EDA | electrodermal activity |

| EEG | electroencephalography |

| EMG | electromyography |

| GRU | gated recurrent unit |

| GSR | galvanic skin response |

| HMI | human–machine interface |

| HRV | heart rate variability |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| LOSO | leave-one-subject-out |

| LSTM | long short-term memory |

| MAE | mean absolute error |

| NI | normalized improvement |

| OMS | occupant monitoring system |

| R2 | coefficient of determination |

| RMSE | root mean squared error |

| SC | skin conductance |

| SCL | skin conductance level |

| SCR | skin conductance response |

| SVM | support vector machine |

| TCN | temporal convolutional network |

Appendix A

| Feature-Based Classification (Three Classes) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extra Trees (%) | Random Forest (%) | k-NN (%) | Light GBM (%) | Gradient Boosting (%) | SVM (%) | Logistic Regression (%) | ||

| BA | random split | 82.2 | 78.3 | 70.9 | 59.2 | 39.4 | 37.0 | 35.6 |

| LOSO | 33.3 | 33.1 | 33.0 | 33.2 | 33.0 | 31.4 | 32.6 | |

| NI | random split | +73.3 | +67.5 | +56.4 | +38.8 | +9.1 | +5.5 | +3.4 |

| LOSO | −0.1 | −0.8 | −0.6 | −0.2 | −0.5 | −2.9 | −1.5 | |

| Sequence-Based Classification (Three Classes) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRU (%) | LSTM (%) | CNN-1D (%) | TCN (%) | ||

| BA | random split | 35.1 | 38.7 | 43.8 | 87.0 |

| LOSO | 33.8 | 34.3 | 33.8 | 33.5 | |

| NI | random split | +2.6 | +8.1 | +15.7 | +80.5 |

| LOSO | +0.7 | +1.4 | +0.7 | +0.3 | |

| Extra Trees | Random Forest | LGBM Regressor | Gradient Boosting | XGB Regressor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE (−) | 20.386 | 16.820 | 18.579 | 26.200 | 18.016 |

| RMSE (−) | 23.577 | 19.733 | 21.833 | 29.967 | 21.321 |

| (−) | 0.446 | 0.612 | 0.525 | 0.105 | 0.547 |

| GRU | LSTM | CNN-1D | TCN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE (−) | 27.943 | 27.941 | 27.301 | 14.588 |

| RMSE (−) | 31.672 | 31.672 | 31.108 | 18.779 |

| (−) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.648 |

References

- Pei, G.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hua, S.; Li, T. Affective computing: Recent advances, challenges, and future trends. Intell. Comput. 2024, 3, 0076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, G.; Zhang, X.P. Recent Progress of Optical Imaging Approaches for Noncontact Physiological Signal Measurement: A Review. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 2200345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurnaningsih, D.; Adi, K.; Surarso, B. Real Time Driver Drowsiness Detection Using ViViT for In Vehicle Monitoring Systems Under Diverse Driving Conditions. Int. J. Transp. Dev. Integr. 2025, 9, 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Reolid, R.; López de la Rosa, F.; Sánchez-Reolid, D.; López, M.T.; Fernández-Caballero, A. Machine learning techniques for arousal classification from electrodermal activity: A systematic review. Sensors 2022, 22, 8886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.R.; Parrish, J.A. The Optics of Human Skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1981, 77, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamboa, P.; Varandas, R.; Mrotzeck, K.; Silva, H.P.d.; Quaresma, C. Electrodermal Activity Analysis at Different Body Locations. Sensors 2025, 25, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tronstad, C.; Amini, M.; Bach, D.R.; Martinsen, Ø.G. Current trends and opportunities in the methodology of electrodermal activity measurement. Physiol. Meas. 2022, 43, 02TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, J.J.; Watson, D.G.; Jones, R.; Rowe, M. A guide for analysing electrodermal activity (EDA) & skin conductance responses (SCRs) for psychological experiments. Psychophysiology 2013, 49, 1017–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, U.; Shetty, A.D. Electrodermal Activity (EDA) for Treatment of Neurological and Psychiatric Disorder Patients: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India, 19–20 March 2021; Volume 1, pp. 1424–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Fu, L.; Jiang, C.; Wen, C. Driver fatigue detection using measures of heart rate variability and electrodermal activity. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 25, 5510–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernat, R.A.; Speriatu, A.M.; Taralunga, D.D.; Hurezeanu, B.E.; Nicolae, I.E.; Strungaru, R.; Ungureanu, G.M. Stress influence on drivers identified by monitoring galvanic skin resistance and heart rate variability. In Proceedings of the 2017 E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB), Sinaia, Romania, 22–24 June 2017; pp. 261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wu, C.; Nie, B.; Li, S.E. Sensitivity of electrodermal activity features for driver arousal measurement in cognitive load: The application in automated driving systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 14954–14967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zontone, P.; Affanni, A.; Bernardini, R.; Piras, A.; Rinaldo, R. Stress detection through electrodermal activity (EDA) and electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis in car drivers. In Proceedings of the 2019 27th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), A Coruña, Spain, 2–6 September 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Affanni, A.; Piras, A.; Rinaldo, R.; Zontone, P. Dual channel Electrodermal activity sensor for motion artifact removal in car drivers’ stress detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium (SAS), Sophia Antipolis, France, 11–13 March 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Benedek, M.; Kaernbach, C. A continuous measure of phasic electrodermal activity. J. Neurosci. Methods 2010, 190, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Li, W.; Li, Z.; Maguluri, G.; Grimble, J.; Bonatt, J.; Miske, J.; Iftimia, N.; Lin, S.; Grimm, M. Smart Steering Sleeve (S3): A Non-Intrusive and Integrative Sensing Platform for Driver Physiological Monitoring. Sensors 2022, 22, 7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnecke, J.M.; Ganapathy, N.; Koch, E.; Dietzel, A.; Flormann, M.; Henze, R.; Deserno, T.M. Printed and Flexible ECG Electrodes Attached to the Steering Wheel for Continuous Health Monitoring during Driving. Sensors 2022, 22, 4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babusiak, B.; Hajducik, A.; Medvecky, S.; Lukac, M.; Klarak, J. Design of Smart Steering Wheel for Unobtrusive Health and Drowsiness Monitoring. Sensors 2021, 21, 5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Hermans, A.; Leibe, B. 2D vs. 3D LiDAR-based Person Detection on Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 3604–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamborae, M.; Schneider, E.N.; Flotho, P.; Francis, A.; Strauss, D.J. LumEDA: Image luminance based contactless correlates of electrodermal responses. Physiol. Meas. 2025, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamborae, M.J.; Flotho, P.; Mai, A.; Schneider, E.N.; Francis, A.L.; Strauss, D.J. Towards Contactless Estimation of Electrodermal Activity Correlates. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 1799–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, M.; Tsumura, N. Detecting wetness on skin using rgb camera. In Proceedings of the Color and Imaging Conference, Society for Imaging Science and Technology, Paris, France, 21–25 October 2019; Volume 27, pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Adib, F.; Mao, H.; Kabelac, Z.; Katabi, D.; Miller, R.C. Smart Homes that Monitor Breathing and Heart Rate. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 18–23 April 2015; CHI’15. pp. 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, N.; Rouvala, M.; Kaarna, A. Vital Sign Detection Using Short-range mm-Wave Pulsed Radar. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 3rd Global Conference on Life Sciences and Technologies (LifeTech), Nara, Japan, 9–11 March 2021; pp. 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B.; Kong, Y.; Posada-Quintero, H.F.; Chon, K.H. Comparison of electrodermal activity from multiple body locations based on standard EDA indices’ quality and robustness against motion artifact. Sensors 2022, 22, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dooren, M.; Janssen, J.H. Emotional sweating across the body: Comparing 16 different skin conductance measurement locations. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, T.; Tsuda, T.; Kitagawa, S.; Naitoh, K.; Nakashima, K.; Ohhashi, T. Physical stimuli and emotional stress-induced sweat secretions in the human palm and forehead. Anal. Chim. Acta 1998, 365, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.T.; Long Ton, T.; Minh Nguyen, N.T.; Duong Nguyen, B. A K-band Noninvasive Vital Signs Monitoring System in Automotive Applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ISEE), Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam, 10–12 October 2019; pp. 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharamohammadi, A.; Dabak, A.G.; Yang, Z.; Khajepour, A.; Shaker, G. Volume-Based Occupancy Detection for In-Cabin Applications by Millimeter Wave Radar. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S. In-Cabin Monitoring System for Autonomous Vehicles. Sensors 2022, 22, 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, J.; Aycard, O.; Baber, J. Efficient Detection and Tracking of Human Using 3D LiDAR Sensor. Sensors 2023, 23, 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, B.; Lozano, S.; Banaji, M.R. Introducing the open affective standardized image set (OASIS). Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benewake. TFmini-S LiDAR, Micro LiDAR Sensor—Benewake—en.benewake.com. Available online: https://en.benewake.com/TFminiS/index.html (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Raspberry Pi Foundation. Raspberry Pi 5 Product Brief. 2023. Available online: https://www.raspberrypi.com/products/raspberry-pi-5/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Grove—GSR Sensor | Seeed Studio Wiki—wiki.seeedstudio.com. Available online: https://wiki.seeedstudio.com/Grove-GSR_Sensor/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Makowski, D.; Pham, T.; Lau, Z.J.; Brammer, J.C.; Lespinasse, F.; Pham, H.; Schölzel, C.; Chen, S.H.A. NeuroKit2: A Python toolbox for neurophysiological signal processing. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubba, C.H.; Sethi, S.S.; Knaute, P.; Schultz, S.R.; Fulcher, B.D.; Jones, N.S. Catch22: CAnonical Time-series CHaracteristics: Selected through highly comparative time-series analysis. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 33, 1821–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 8026–8037. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharamohammadi, A.; Khajepour, A.; Shaker, G. In-Vehicle Monitoring by Radar: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 25650–25672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Park, C.; Lee, B. Tracking driver’s heart rate by continuous-wave Doppler radar. In Proceedings of the 2016 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA, 16–20 August 2016; pp. 5417–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Azou, S.; Youssef, R.; Morel, P.; Radoi, E. IR-UWB Radar-Based Robust Heart Rate Detection Using a Deep Learning Technique Intended for Vehicular Applications. Electronics 2022, 11, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature-Based Classifiers | Sequence-Based Classifiers |

|---|---|

| Extra Trees | Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) |

| Random Forest | Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) | 1D Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) |

| Light GBM | Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) |

| Gradient Boosting | |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | |

| Logistic Regression |

| Feature-Based Regressors | Sequence-Based Regressors |

|---|---|

| Extra Trees Regressor | Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) |

| Random Forest Regressor | Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) |

| LightGBM Regressor | 1D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN-1D) |

| Gradient Boosting Regressor | Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) |

| XGBoost Regressor |

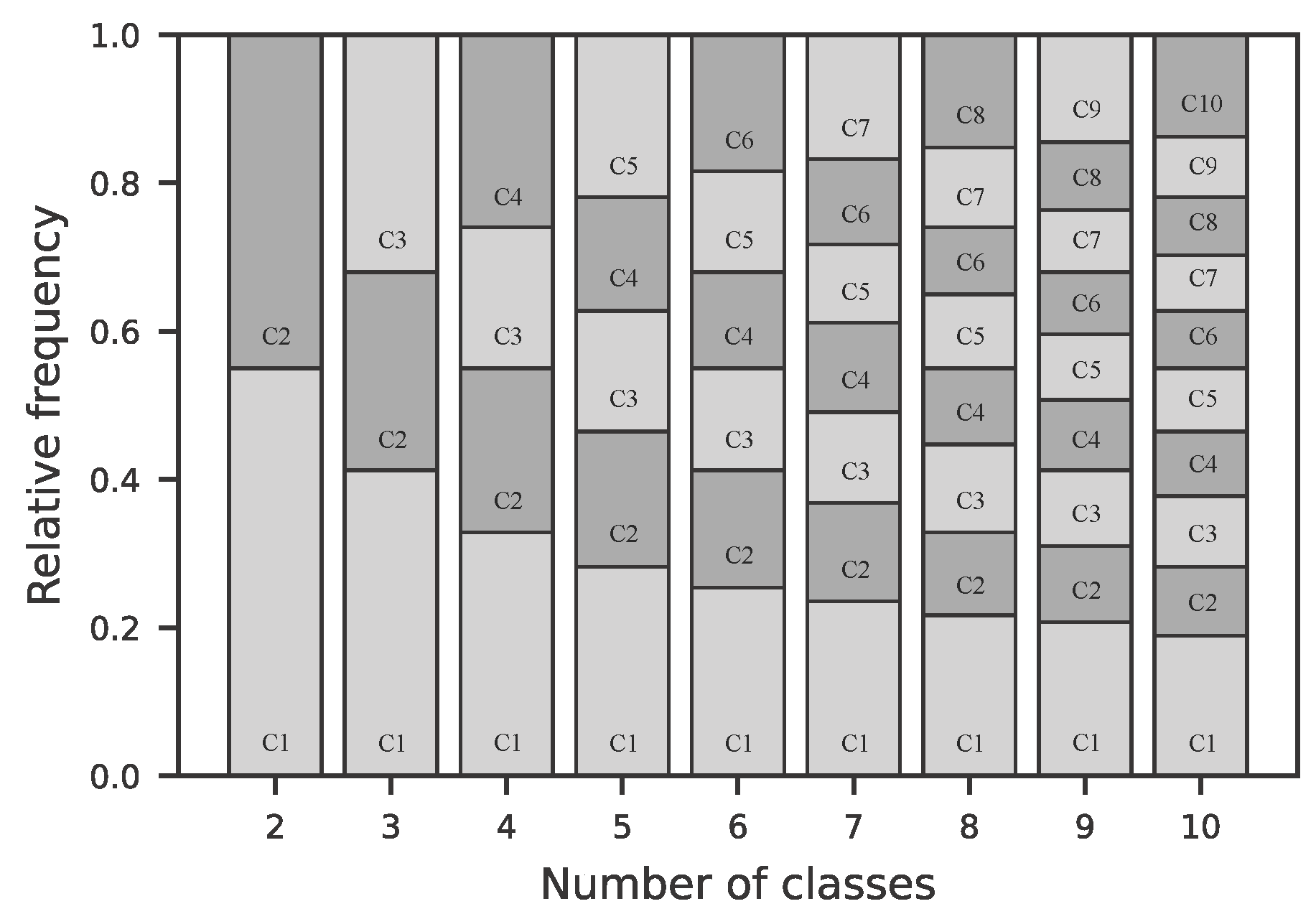

| Number of Classes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Imbalance Ratio | 1.22 | 1.54 | 1.73 | 1.84 | 1.96 | 2.23 | 2.39 | 2.48 | 2.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brandstetter, J.; Knoch, E.-M.; Gauterin, F. Towards In-Vehicle Non-Contact Estimation of EDA-Based Arousal with LiDAR. Sensors 2025, 25, 7395. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237395

Brandstetter J, Knoch E-M, Gauterin F. Towards In-Vehicle Non-Contact Estimation of EDA-Based Arousal with LiDAR. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7395. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237395

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrandstetter, Jonas, Eva-Maria Knoch, and Frank Gauterin. 2025. "Towards In-Vehicle Non-Contact Estimation of EDA-Based Arousal with LiDAR" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7395. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237395

APA StyleBrandstetter, J., Knoch, E.-M., & Gauterin, F. (2025). Towards In-Vehicle Non-Contact Estimation of EDA-Based Arousal with LiDAR. Sensors, 25(23), 7395. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237395