Simulation and Experiment of Tilted Fiber Bragg Grating Humidity Sensor Coated with PVA/GO Nanofiber Films by Electrospinning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sensor Simulation

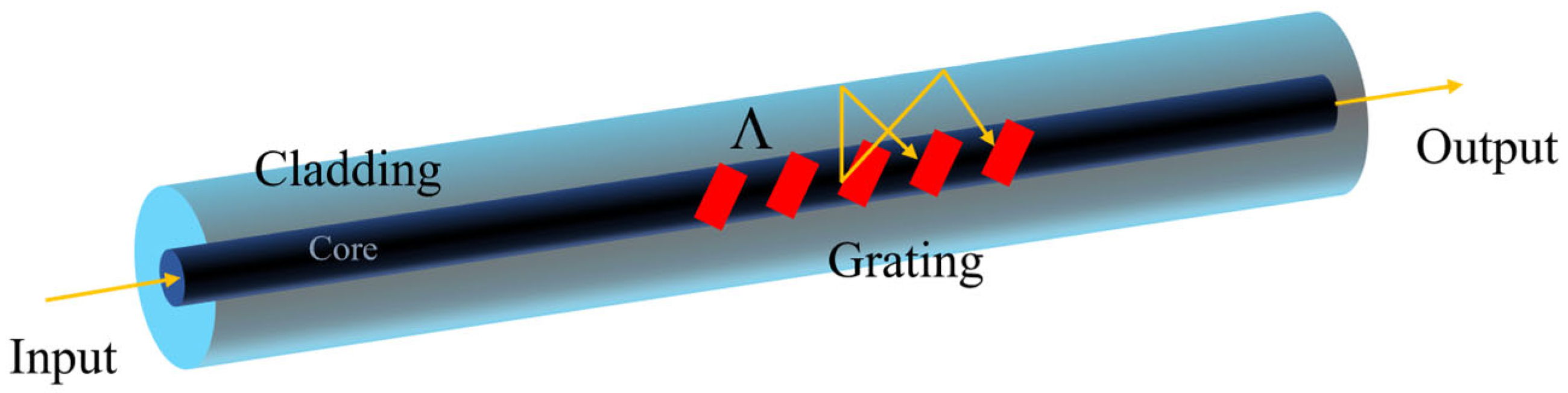

2.1. Operating Principle

2.2. TFBG Parameter Simulation

- (1)

- The TFBG tilt angle was set to 6°, 8°, 10°, and 12°. The TFBG length and period were set to 1 cm and 535 nm. The simulated transmission spectra of different tilt angles are shown in Figure 2a. It can be seen that as the TFBG tilt angle increases, the core mode and cladding modes shift toward the long-wavelength direction. The distance between the core mode and the cladding modes increases, and more cladding modes appear, broadening the transmission spectrum. The tilt angle of the 8° spectrum exhibits a stronger core mode and more cladding modes, so we selected the TFBG tilt angle of 8°.

- (2)

- The TFBG period was set to 525 nm, 530 nm, 535 nm, 540 nm, and 545 nm, with a tilt angle of 8° and a length of 1 cm. The simulated transmission spectra of different periods are shown in Figure 2b. As the grating period increases, both the core mode and cladding modes shift toward the long-wavelength direction, while the transmission depth remains similar. This characteristic allows for the adjustment of grating periods to position the transmission spectrum within a specific band. We selected the TFBG period of 535 nm to make the central wavelength of the transmission spectrum 1550 nm.

- (3)

- The TFBG length was set to 0.5 cm, 1 cm, 1.5 cm, and 2 cm. The TFBG tilt angle and period were set to 8° and 535 nm. The simulated transmission spectra of different lengths are shown in Figure 2c. As the grating length increases, the transmission depth increases. However, an excessively long grating length can compromise the mechanical strength of the optical fiber. To balance mechanical strength and transmission depth, we selected a grating length of 1 cm, ensuring both high mechanical strength and a deep transmission spectrum.

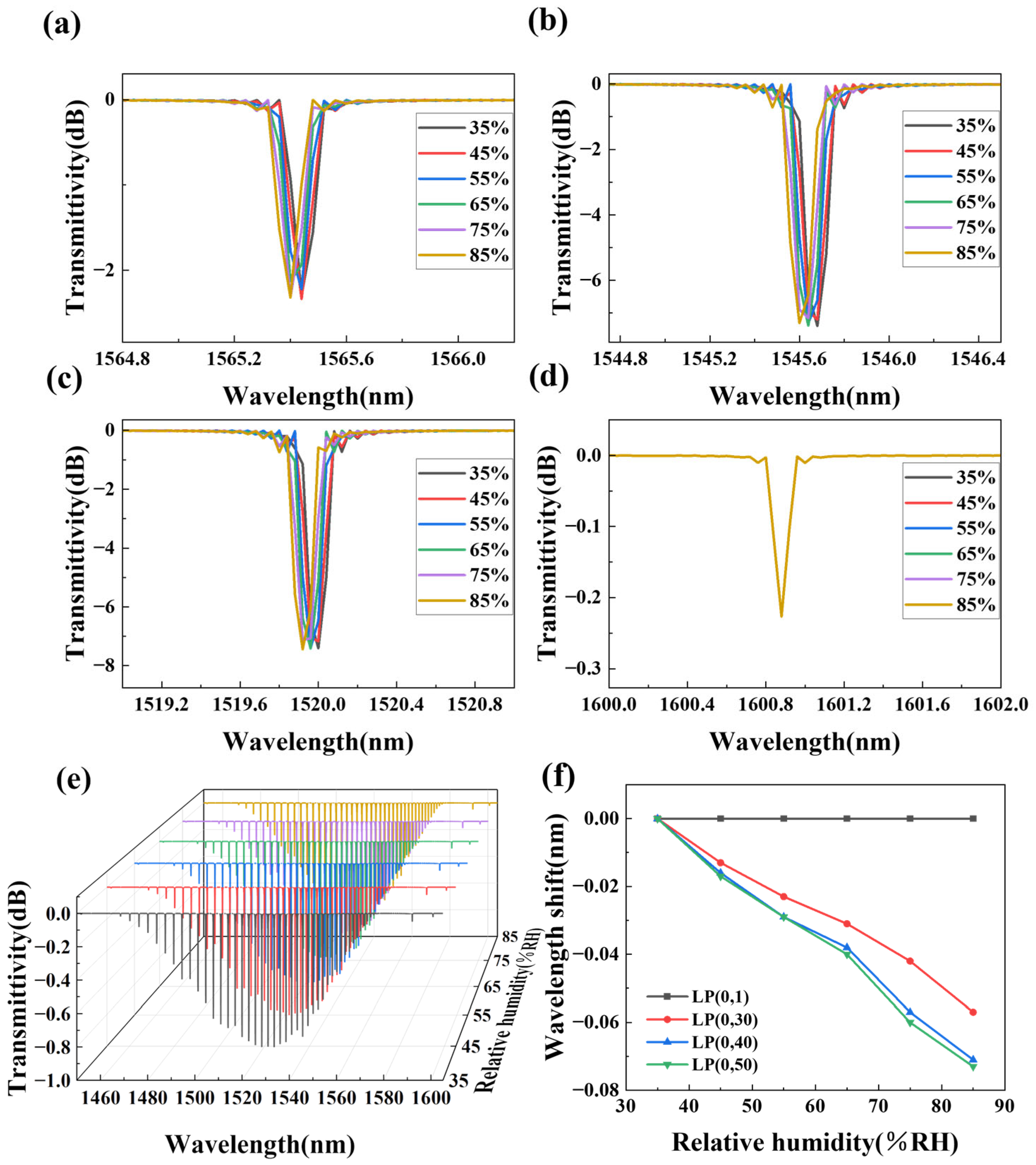

2.3. TFBG Sensor Simulation

2.3.1. TFBG Humidity Simulation

2.3.2. TFBG Temperature Simulation

3. Materials and Methods

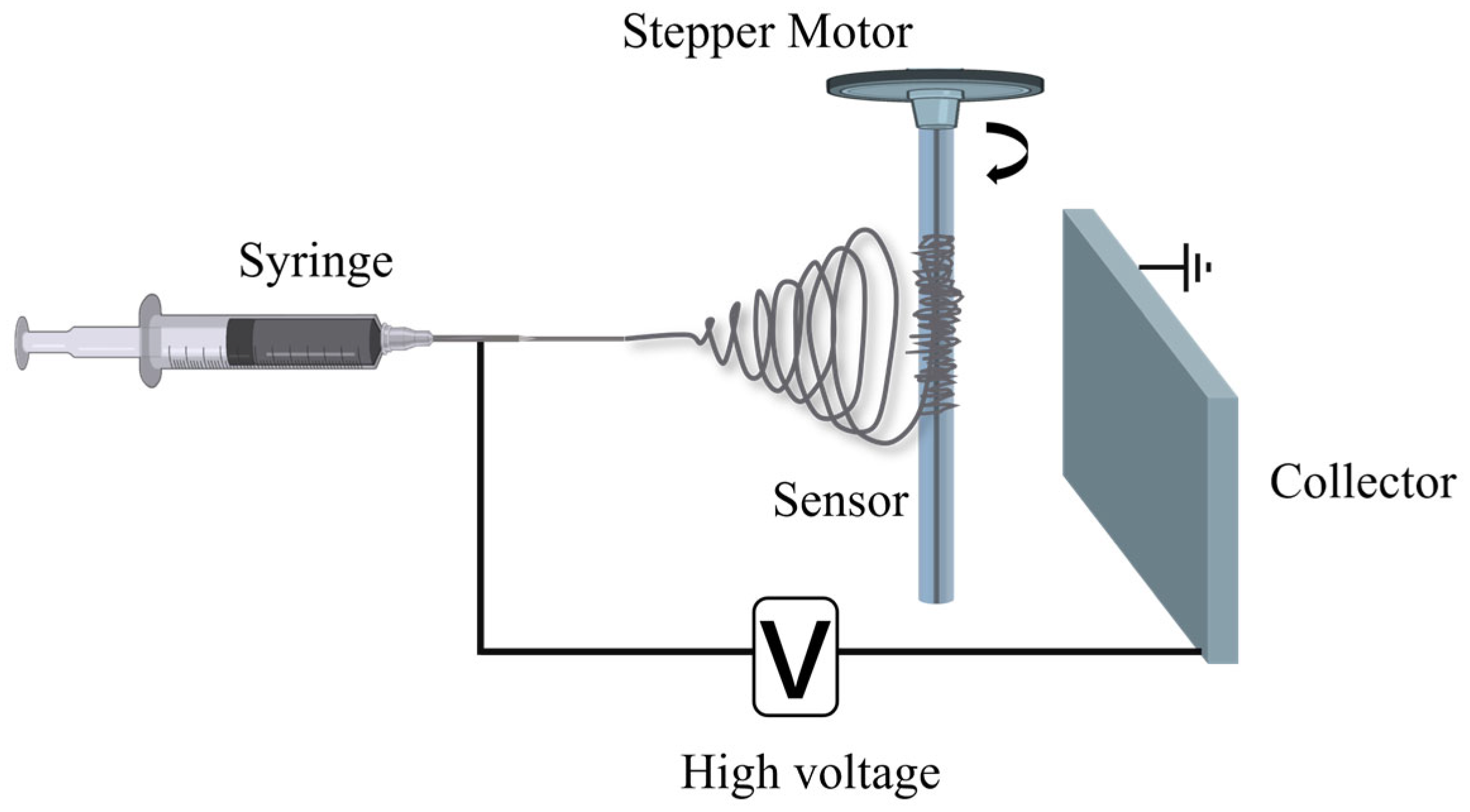

3.1. Electrospinning

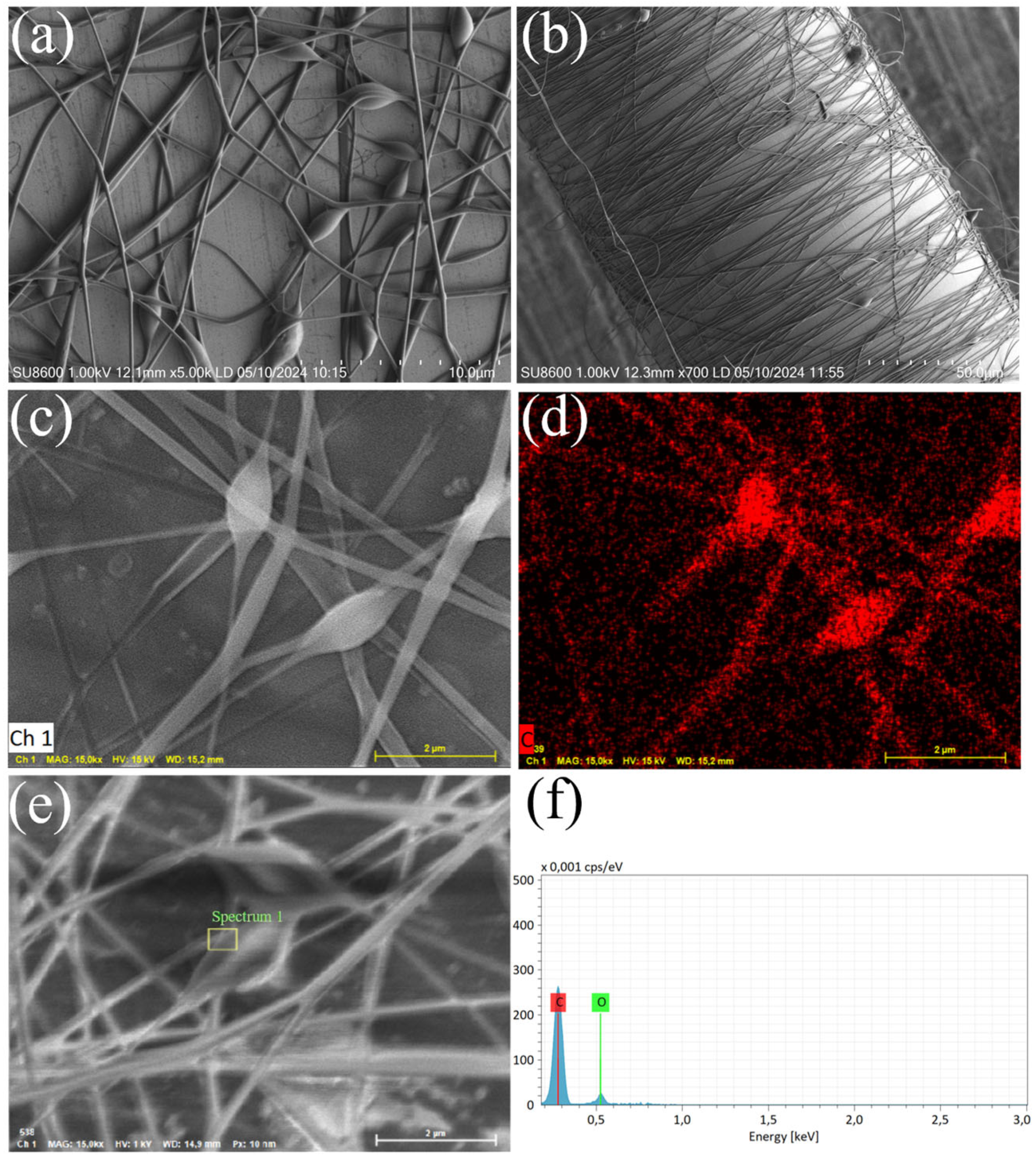

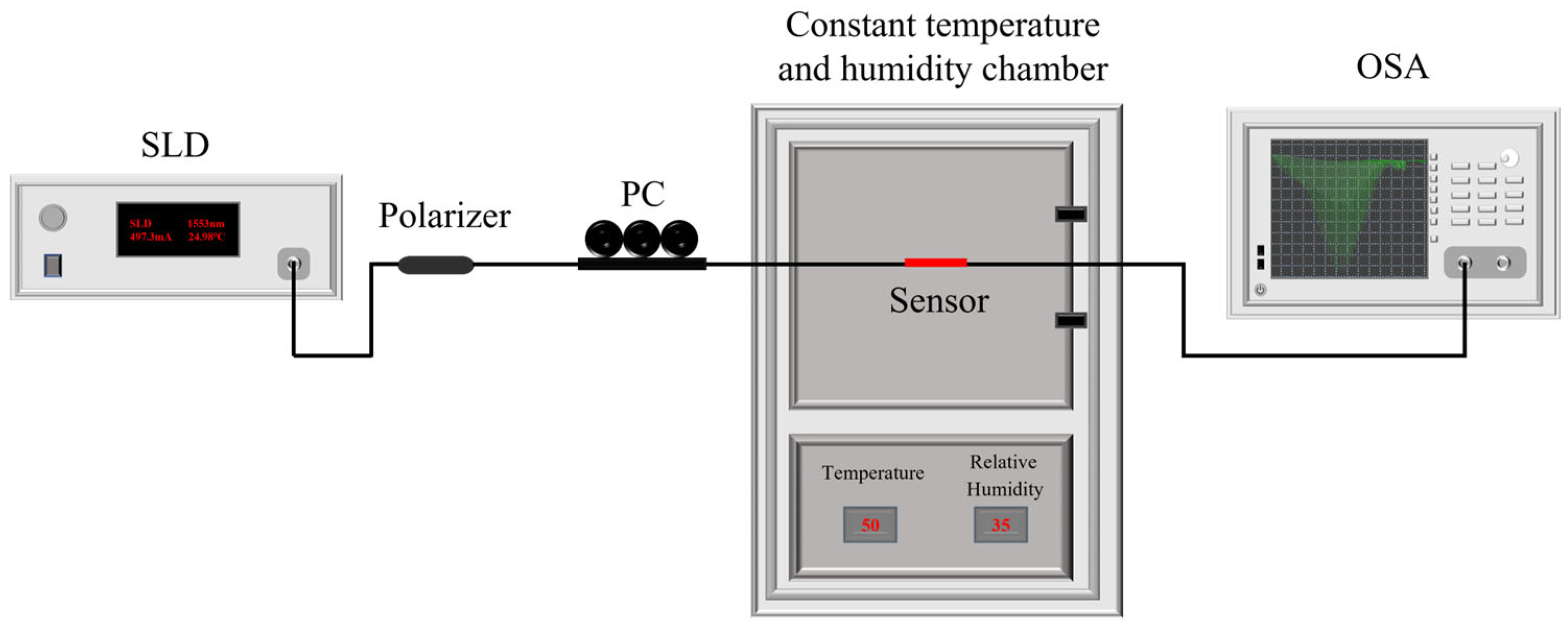

3.2. Characterization of TFBG Sensor

4. Experiment Results and Discussions

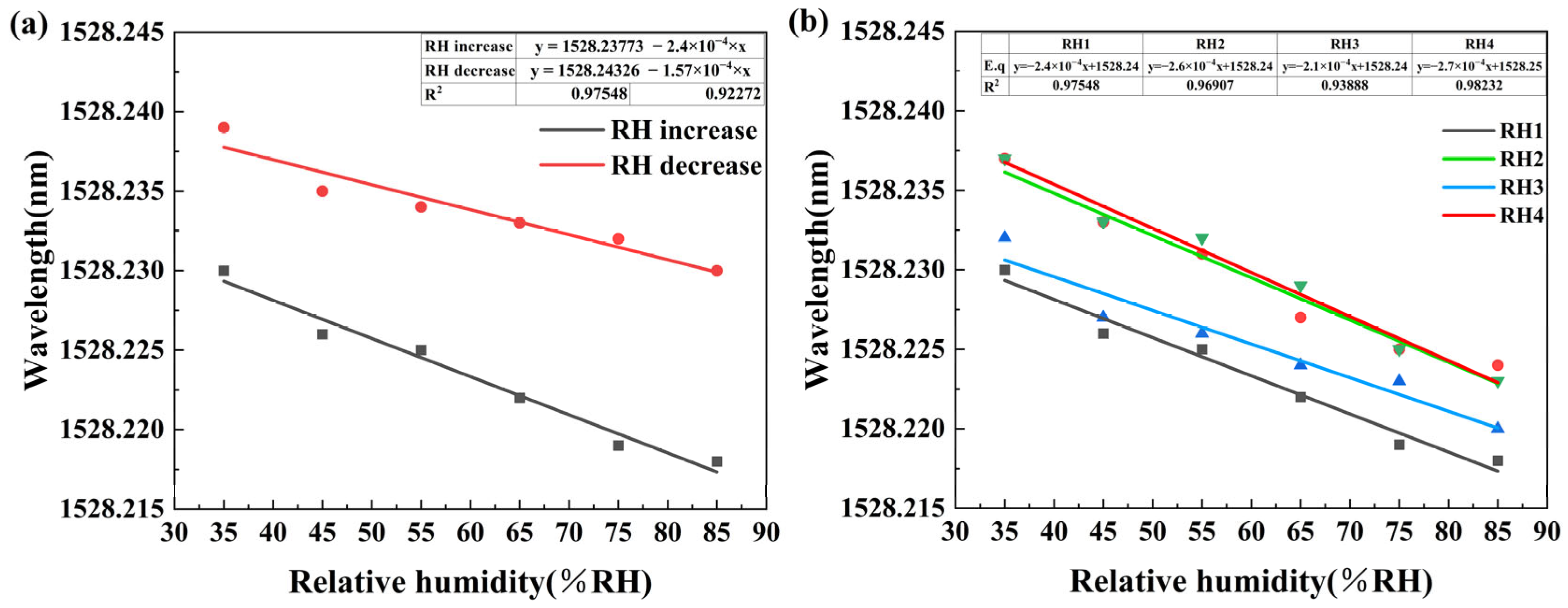

4.1. Humidity Test

4.2. Repeatability Test

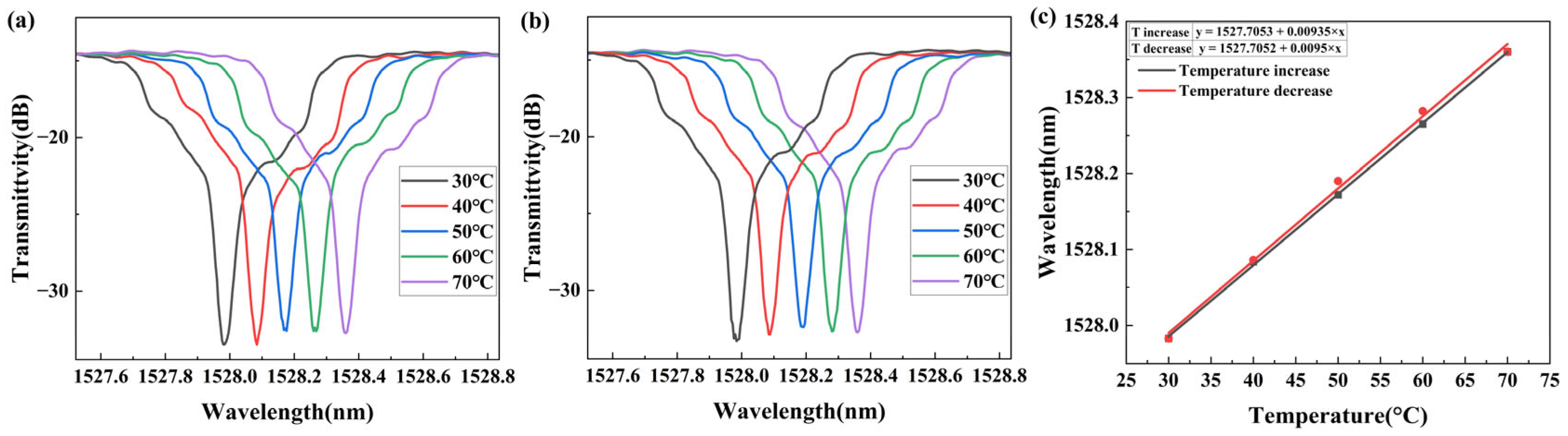

4.3. Temperature Test

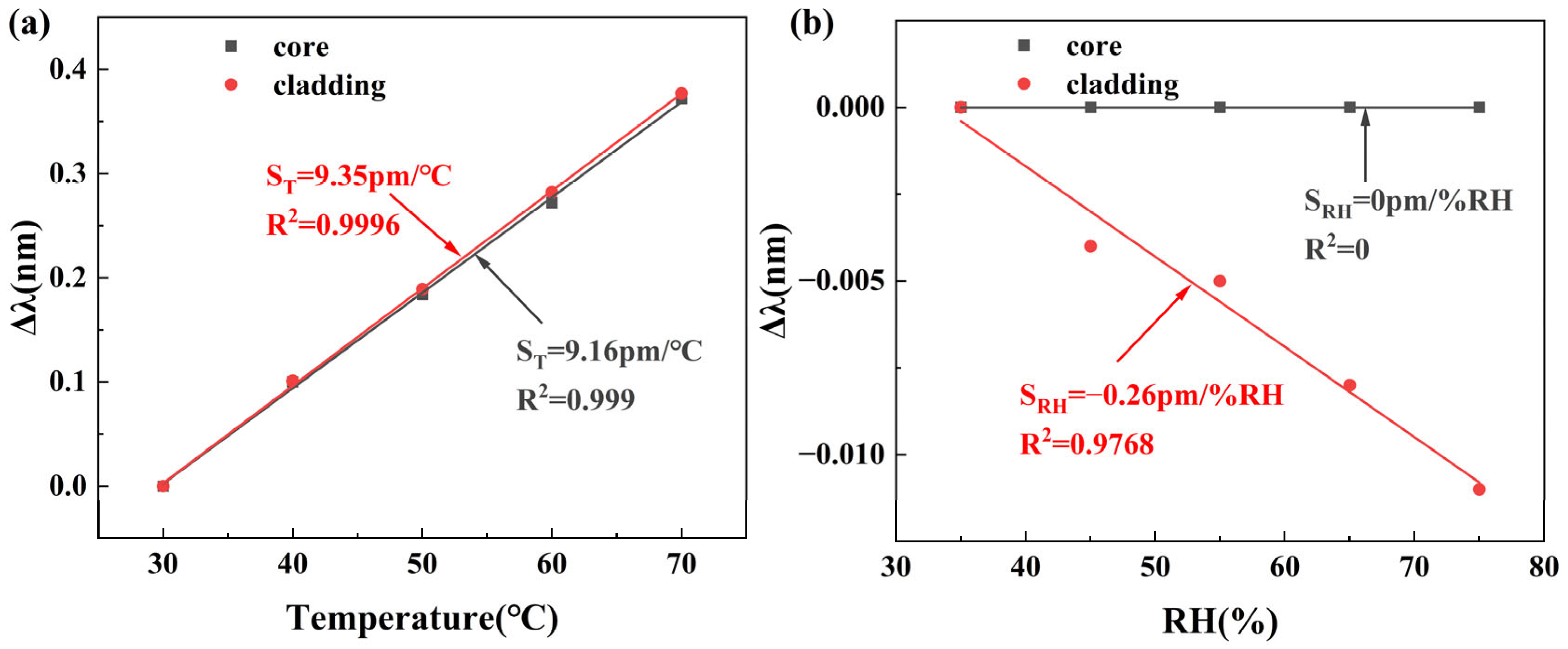

4.4. Temperature Compensation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giallorenzi, T.G.; Bucaro, J.A.; Dandridge, A.; Sigel, G.H.; Cole, J.H.; Rashleigh, S.C.; Priest, R.G. Optical fiber sensor technology. IEEE Microw. Theory 1982, 30, 472–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Zhong, N.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Chang, H.; Wan, B.; Zhong, D.; Xie, Q. Fiber Bragg grating sensor for accurate and sensitive detection of carbon dioxide concentration. Sens. Actuatorsors B-Chem. 2024, 404, 135264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Wang, Z.; Ye, Y.; Teng, C.; Min, R. PDMS-embedded wearable FBG sensors for gesture recognition and communication assistance. Biomed. Opt. Express 2024, 15, 1892–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Yang, B.; Xu, Z.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Sun, D.; Ma, J. High-performance optical fiber differential urea sensing system for trace urea concentration detection with enhanced sensitivity using liquid crystals. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2024, 417, 136077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xu, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Ma, J.; Sun, L. Multi-parameter information detection of aircraft taxiing on an airport runway based on an ultra-weak FBG sensing array. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 25135–25146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Li, Z.; Fu, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Jiang, D. Distributed optical fiber sensing and applications based on large-scale fiber Bragg grating array. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 4187–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Xie, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, D.; Wang, H. Quasi-distributed optical fiber sensing for the coupled vibration analysis of high-speed train-bridge coupled system under earthquakes. Sens. Actuatorsors A-Phys. 2024, 374, 115422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Junior, A.; Silveira, M.; Pires-Junior, R.; Frizera, A.; Blanc, W.; Marques, C. NP-doped fiber smart tendon: A millimeter-scale 3D shape reconstruction with embedded distributed optical fiber sensor system. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 14291–14299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chang, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, H. Single-walled carbon nanowires-integrated SPR biosensors: A facile approach for direct detection of exosomal PD-L1. Sensor Actuators B-Chem. 2024, 399, 134795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, C.; Shi, C.; Wang, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z. Spiral cone fiber SPR sensor for detecting ginsenoside Rg1. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 13783–13796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Meng, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, D.; Xu, Z.; Wei, L.; Niu, H.; Yang, S.; Yuan, L. Multi-channel seven-core fiber SPR sensor without temperature and channel crosstalk. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 42, 2144–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Shao, P.; Min, R.; Deng, H.; Chen, M.; Deng, S.; Hu, X.; Marques, C.; Yuan, L. Simultaneous measurement of refractive index and temperature based on a side-polish and V-groove plastic optical fiber SPR sensor. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, R.; Wang, Z.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q. Smart photonic wristband for pulse wave monitoring. Opto-Electron. Sci. 2024, 3, 240009-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Doddamani, A. Role of sensor in the food processing industries. Int. Arch. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, Y.; Wang, W.; Lin, C.; He, X. Functional optical fiber sensors detecting imperceptible physical/chemical changes for smart batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, X.; Yang, J.; Yu, X.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y. Wearable molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor with integrated nanofiber-based microfluidic chip for in situ monitoring of cortisol in sweat. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2023, 381, 133451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Mao, R.; Song, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, H.; Xia, H.; Ma, Y.; Gao, Y. Humidity sensing properties and respiratory behavior detection based on chitosan-halloysite nanotubes film coated QCM sensor combined with support vector machine. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2023, 374, 132824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.B.; Rajagopal, S.; Prieto-Simón, B.; Pogue, B.W. Recent advances in smart wearable sensors for continuous human health monitoring. Talanta 2024, 272, 125817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Ling, Q.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, Z.; Du, K. Lab-on fiber humidity sensor for real-time respiratory rate monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 20663–20668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Brambilla, G.; Fan, Y.; Wang, P. High-performance ultrafast humidity sensor based on microknot resonator-assisted Mach–Zehnder for monitoring human breath. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 3404–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lin, Z.; Dong, S.; Chen, M. Review of wearable optical fiber sensors: Drawing a blueprint for human health monitoring. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 161, 109227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Chen, F.; Lai, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Wearable breath monitoring based on a flexible fiber-optic humidity sensor. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2021, 349, 130794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presti, D.L.; Massaroni, C.; Zaltieri, M.; Sabbadini, R.; Carnevale, A.; Di Tocco, J.; Longo, U.G.; Caponero, M.A.; D’Amato, R.; Schena, E. A magnetic resonance-compatible wearable device based on functionalized fiber optic sensor for respiratory monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 21, 14418–14425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, N.K.; Sohi, P.A.; Kahrizi, M. Polymer based optical humidity and temperature sensor. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 3069–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liehr, S.; Breithaupt, M.; Krebber, K. Distributed humidity sensing in PMMA optical fibers at 500 nm and 650 nm wavelengths. Sensors 2017, 17, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, T.; Freitas, A.I.; Leca, J.M.; Ferreira, M.S.; Nascimento, M. Decoupling temperature and humidity with chitosan-coated tilted FBG sensor. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Optical Fiber Sensors, Porto, Portugal, 25–30 May 2025; Volume 13639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, B.; Carvalho, J.; Mendes, J.; Almeida, J.M.M.M.; Coelho, L.C.C. Analysis of the relative humidity response of hydrophilic polymers for optical fiber sensing. Polymers 2022, 14, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Zhao, K.; Yu, D.-G.; Zheng, X.; Huang, C. Advances in biosensing and environmental monitoring based on electrospun nanofibers. Adv. Fiber. Mater. 2022, 4, 404–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghoraibi, I.; Alomari, S. Different methods for nanofiber design and fabrication. Handb. Nanofibers 2018, 1, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wu, T.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: Methods, materials, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 5298–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Jian, J.; Tu, T.; Yang, Z.; Ling, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Tian, H.; Yang, Y. Wearable humidity sensor based on porous graphene network for respiration monitoring. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 116, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Bi, Z.; Hao, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Feng, D.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, L.; Gan, X.; Zhao, J. Graphene oxide-deposited tilted fiber grating for ultrafast humidity sensing and human breath monitoring. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2019, 293, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolzhenko, E.I.; Tomyshev, K.; Butov, O.V. A Poly (vinyl alcohol) Coating Method for a Tilted-Fiber Bragg-Grating-Assisted Fiber Hygrometer. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL)–Rapid Res. Lett. 2020, 14, 2000435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Lu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, C.; Peng, W. High sensitivity humidity detection based on functional GO/MWCNTs hybrid nano-materials coated titled fiber Bragg grating. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Li, B.; Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Suzuki, T.; Ohishi, Y.; Wang, F. A surface plasmon resonance optical fiber sensor for simultaneous measurement of relative humidity and temperature. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 3246–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zheng, H.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; Xi, J.; Deng, L.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, J. SnO2/polyvinyl alcohol nanofibers wrapped tilted fiber grating for high-sensitive humidity sensing and fast human breath monitoring. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2023, 388, 133807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Jia, A.; Hu, J.; Li, G.; Wang, W.; Li, M.; Han, D.; Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Liang, L. Polyvinyl alcohol nanofibers wrapped microtapered long-period fiber grating for high-linearity humidity and temperature sensing. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 6279–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonazzi, C.; Ripoche, A.; Michon, C. Moisture diffusion in gelatin slabs by modeling drying kinetics. Dry. Technol. 1997, 15, 2045–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looyenga, H. Dielectric constants of heterogeneous mixtures. Physica 1965, 31, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.F.; Antunes, P.; Pecoraro, E.; Lima, P.P.; Varum, H.; Carlos, L.D.; Ferreira, R.A.; André, P.S. Optical fiber relative humidity sensor based on a FBG with a di-ureasil coating. Sensors 2012, 12, 8847–8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-D.; Wu, C.-W.; Chiang, C.-C. Tilted fiber Bragg grating sensor with graphene oxide coating for humidity sensing. Sensors 2017, 17, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.-Y.; Shi, B.; Sun, M.-Y.; Zhang, C.-C.; Wei, G.-Q.; Liu, J. Characterization of an ORMOCER®-coated FBG sensor for relative humidity sensing. Measurement 2021, 171, 108851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, P.; Prakash, O.; Kumar, J.; Purbia, G.; Mukherjee, C.; Dixit, S.; Nakhe, S. Relative humidity measurement sensor based on polyvinyl alcohol coated tilted fiber Bragg grating. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 125123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.-Y.; Huang, W.-Y.; Huang, T.-S.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Chiang, C.-C. Comparison of the sensing mechanisms and capabilities of three functional materials surface-modified TFBG sensors. Aip Adv. 2020, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensor | Coating Material | Advantage | Disadvantage | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBG | Polyimide | Reversible expansion | Higher T required | [24] |

| POF | PMMA | Stability | Slow response time | [25] |

| TFBG | Chitosan | Amino/carboxyl-rich | Hardly soluble | [26] |

| FPI/LPFG | PVA/PEG/agar/Hydromed D4 | PEG: thick coating. Hydromed D4: optical stability. Agar: higher RI changes. PVA: suitable for RH sensing. | PEG: No information below DRH. Hydromed D4: low sensing response. Agar: needs heating. | [27] |

| RH | 35% | 45% | 55% | 65% | 75% | 85% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI | 1.4847 | 1.4832 | 1.4812 | 1.4792 | 1.4772 | 1.4749 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, L.; Sun, H.; Xi, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Jian, C.; Li, X.; Li, J. Simulation and Experiment of Tilted Fiber Bragg Grating Humidity Sensor Coated with PVA/GO Nanofiber Films by Electrospinning. Sensors 2025, 25, 7386. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237386

Deng L, Sun H, Xi J, Yang Y, Liu X, Jian C, Li X, Li J. Simulation and Experiment of Tilted Fiber Bragg Grating Humidity Sensor Coated with PVA/GO Nanofiber Films by Electrospinning. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7386. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237386

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Li, Hao Sun, Jiawei Xi, Yanxin Yang, Xin Liu, Chaochao Jian, Xiang Li, and Jinze Li. 2025. "Simulation and Experiment of Tilted Fiber Bragg Grating Humidity Sensor Coated with PVA/GO Nanofiber Films by Electrospinning" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7386. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237386

APA StyleDeng, L., Sun, H., Xi, J., Yang, Y., Liu, X., Jian, C., Li, X., & Li, J. (2025). Simulation and Experiment of Tilted Fiber Bragg Grating Humidity Sensor Coated with PVA/GO Nanofiber Films by Electrospinning. Sensors, 25(23), 7386. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237386