4.2. Quantitative Results

We conduct a systematic evaluation of the widely-used KITTI tracking benchmark to comprehensively validate the effectiveness of the proposed lightweight tracking method via collaborative camera and LiDAR sensors for the 3D multi-object tracking task. Given that existing studies are typically optimized for specific object categories (e.g., cars or pedestrians), we accordingly performed detailed comparisons between our method and current state-of-the-art approaches separately for both the Car and Pedestrian categories. The results demonstrate that our method outperforms existing techniques across multiple key metrics. The detailed evaluation results are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2. For clarity in presenting the performance ranking, the top first, second, and third methods for each metric are highlighted in red, blue, and green, respectively. An upward arrow (↑) denotes higher values are better, while a downward arrow (↓) signifies lower values are preferable.

As evidenced by the comprehensive comparison in

Table 1 and

Table 2, the proposed lightweight 3D multi-object tracking method via collaborative camera and LiDAR sensors achieves highly competitive results on the KITTI test set. It demonstrates significant advantages across multiple key metrics, particularly in HOTA, AssA, LocA, MOTP, and IDSW. This superior performance is primarily attributed to the synergistic effect of the three proposed core modules. Firstly, the Confidence Inverse-Normalization-Guided Ghost Trajectories Suppression (CIGTS) module significantly enhances the discriminative capability for objects by recovering the original confidence distribution, effectively suppressing false positives and reducing missed detections. Consequently, this leads to a reduction in FP and FN metrics and an improvement in LocA. Compared to the baseline model, our method reduces the FP and FN metrics by 21.3% and 20.1%, respectively. Secondly, the Adaptive Matching Space-Driven Lightweight Association (AMSLA) module discards the redundant global matching strategy. It adaptively defines the matching range based on object confidence and constructs a highly discriminative association cost matrix by incorporating low-complexity motion and geometric features. This approach significantly improves association accuracy while substantially reducing computational costs, leading to notable improvements in the AssA and IDSW metrics. Finally, the Multi-Factor Collaborative Perception-based Intelligent Trajectory Management (MFCTM) module accurately distinguishes between occluded objects and exiting objects through multi-dimensional state assessment of unmatched trajectories. This strategy not only avoids premature deletion of valid trajectories but also promptly terminates redundant ones, thereby preventing incorrect associations. Consequently, it further reduces IDSW while simultaneously improving the MOTP metric.

The pedestrian category is characterized by smaller object size, weaker appearance features, frequent occlusion, and non-rigid motion, presenting significant challenges in distinguishing false positives from true objects, and exiting objects from temporarily occluded ones. As shown in

Table 2, for the pedestrian tracking task, the proposed method achieves first place in HOTA, AssA, and IDSW metrics, and secures second place in LocA, MOTA, and MOTP metrics. These results convincingly demonstrate the effectiveness of our method in tracking non-rigid, small-scale, and easily occluded objects.

4.3. Ablation Experiments

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conduct component-wise ablation studies on the KITTI training set for the three core modules: the CIGTS module, the AMSLA module, and the MFCTM module. These studies aim to quantify the contribution of each module to the overall tracking performance. The experiments employ the official KITTI benchmark evaluation metrics, including HOTA, MOTA, MOTP, FP, FN, and IDSW. Among these, HOTA, MOTA, and MOTP are positive metrics where higher values indicate better performance, whereas FP, FN, and IDSW are negative metrics for which lower values signify superior tracking results. The detailed ablation study results are presented in

Table 3.

As evidenced in

Table 3, incorporating the CIGTS module into the baseline model yields marked improvements across all evaluation metrics. This enhancement is primarily attributed to the module’s ability to perform inverse normalization on detection confidence, which sharpens the distinction between true objects and false positives. Concurrently, the introduction of virtual trajectories and a hierarchical activation mechanism effectively suppresses ghost trajectories caused by false positives while mitigating the risk of losing true objects due to threshold sensitivity. Replacing the original association strategy in the baseline model with the AMSLA module further elevates multiple tracking performance metrics. This improvement stems from the module’s abandonment of the computationally redundant global matching strategy in favor of adaptively defining the matching space based on detection confidence. Furthermore, it constructs a highly discriminative association cost matrix by integrating low-complexity features including Euclidean distance, relative distance, and motion direction angle, thereby significantly enhancing association accuracy while substantially reducing computational overhead. Finally, the integration of all three proposed modules into the baseline model yields the optimal overall performance. This confirms that the MFCTM module also contributes significantly to the overall tracking performance. By comprehensively leveraging multi-source information from unmatched trajectories—including 2D bounding box positions, motion trends, and observation distances—this module intelligently discriminates between temporarily occluded objects and those that have exited the scene. This capability enables precise decisions regarding trajectory retention versus termination, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s tracking robustness and efficiency in complex scenarios.

According to the results in

Table 3, the contribution of each module to the computational efficiency can be clearly observed. First, the introduction of the CIGTS module yields an initial improvement in Frames Per Second (FPS). This is primarily attributed to the module’s ability to filter out a large number of low-quality detections at the source, directly reducing the computational burden for subsequent data association. Furthermore, it effectively suppresses the generation of ghost trajectories, thereby avoiding unnecessary computational overhead during the association and trajectory management stages caused by these false trajectories. Second, the incorporation of the AMSLA module leads to a significant enhancement in FPS. This is mainly because it abandons the computationally redundant global association strategy, performing associations only between detections and trajectories within the same matching space, which substantially reduces the computational complexity of the association process. Additionally, this module avoids using computationally expensive similarity measures, such as appearance information, when constructing the association cost matrix, further optimizing computational efficiency. Finally, the integration of the MFCTM module achieves the highest FPS performance. This stems from its ability to promptly terminate trajectories of objects that have exited the scene. This not only reduces the memory and computational overhead associated with maintaining a large number of active trajectories but also avoids meaningless association attempts with these trajectories in subsequent frames, thereby freeing up computational resources.

During the preprocessing of detection results, the confidence filtering threshold

plays a critical role in distinguishing false positives from true objects. To determine the optimal value for

, we conduct an ablation study, the results of which are summarized in

Table 4.

As shown in

Table 4, the model achieves optimal performance across all evaluation metrics when the confidence filtering threshold

is set to 1.4. This is primarily because an excessively large threshold would incorrectly delete true objects, leading to issues such as missed detections and association failures. Conversely, an overly small threshold would retain a portion of false positives, potentially causing ghost trajectories and identity switches. Furthermore, the value of the confidence stratified threshold

determines the activation period distribution of virtual trajectories. To enable the model to achieve its optimal state, we also conduct an ablation study on

, with the results shown in

Table 5.

As indicated in

Table 5, the model achieves optimal performance when the confidence stratified threshold

is set to 3.5. To further investigate the impact of the activation thresholds on tracking performance, we conduct separate ablation studies for the activation thresholds

and

. The results are presented in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

As shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7, the tracking performance achieves the optimum when the activation thresholds

and

are set to 2 and 3, respectively. This is primarily because a smaller activation threshold increases the likelihood of false detections forming ghost trajectories, thereby leading to incorrect matches and identity switches. Conversely, a larger activation threshold increases the trajectory confirmation time, which subsequently results in association failures and trajectory fragmentation.

In the data association stage, we sequentially incorporate the global distance matrix

, relative distance matrix

, and motion direction matrix

into the proposed association module to evaluate the impact of each association matrix on tracking performance. The results are summarized in

Table 8.

As shown in

Table 8, incorporating the relative distance matrix

into the association cost matrix improves all evaluation metrics. A more substantial performance gain is observed when the motion direction matrix

is further added. This is primarily attributed to the fact that object motion direction can enhance the discriminative power of the relative distance criterion for distinguishing different objects, thereby improving the accuracy of data association and the robustness of tracking. Furthermore, the matching space expansion factor

in the data association module affects the performance of the secondary data association. To explore the optimal performance of our model, we conduct an ablation study on this parameter, with the results presented in

Table 9.

As shown in

Table 9, the model achieves optimal performance when the matching space expansion factor

is set to 1.5. This is primarily because an appropriate expansion factor can effectively handle large inter-frame displacements while simultaneously avoiding the introduction of incorrect matches.

After the object state is determined by the multi-factor collaborative perception-based intelligent trajectory management module, unmatched trajectories corresponding to objects that have left the scene are immediately purged, while those corresponding to temporarily occluded objects are retained as much as possible to address the challenge of long-term occlusion. However, as the number of retention frames increases, the computational cost of the model rises accordingly. Furthermore, the reliability of unmatched trajectories gradually diminishes, leading to an increased probability of incorrect associations. Therefore, we conduct an ablation study on the retention frame count

for unmatched trajectories to determine its optimal value. The results are shown in

Figure 6.

As illustrated in

Figure 6, the evaluation metric HOTA achieves its optimum when the retention frame count

for unmatched trajectories is set to 15, whereas the IDSW metric reaches its minimum at

= 17. To balance model efficiency and performance, we ultimately set the retention frame count

to 15. Subsequently, the value of the perception threshold

in the object state determination strategy also influences tracking performance. Therefore, we conduct an ablation study on the perception threshold

, with the results presented in

Table 10.

As shown in

Table 10, the model fails to achieve optimal performance with either excessively large or small values of the perception threshold

. This occurs primarily because an overly small

tends to misclassify temporarily occluded objects as having left the scene, leading to the premature deletion of their unmatched trajectories. When these objects reappear, identity switches are likely to occur. Conversely, an excessively large

tends to retain unmatched trajectories for objects that have actually left the scene, misclassifying them as temporarily occluded. This increases computational costs and elevates the risk of incorrect associations.

Most parameters in the proposed method maintain stable tracking performance when varied within a reasonable range, indicating low sensitivity to precise parameter values. Moreover, their dependencies are simple and tied to inherent physical constraints, making them insensitive to scene changes and highly generalizable across different environments.

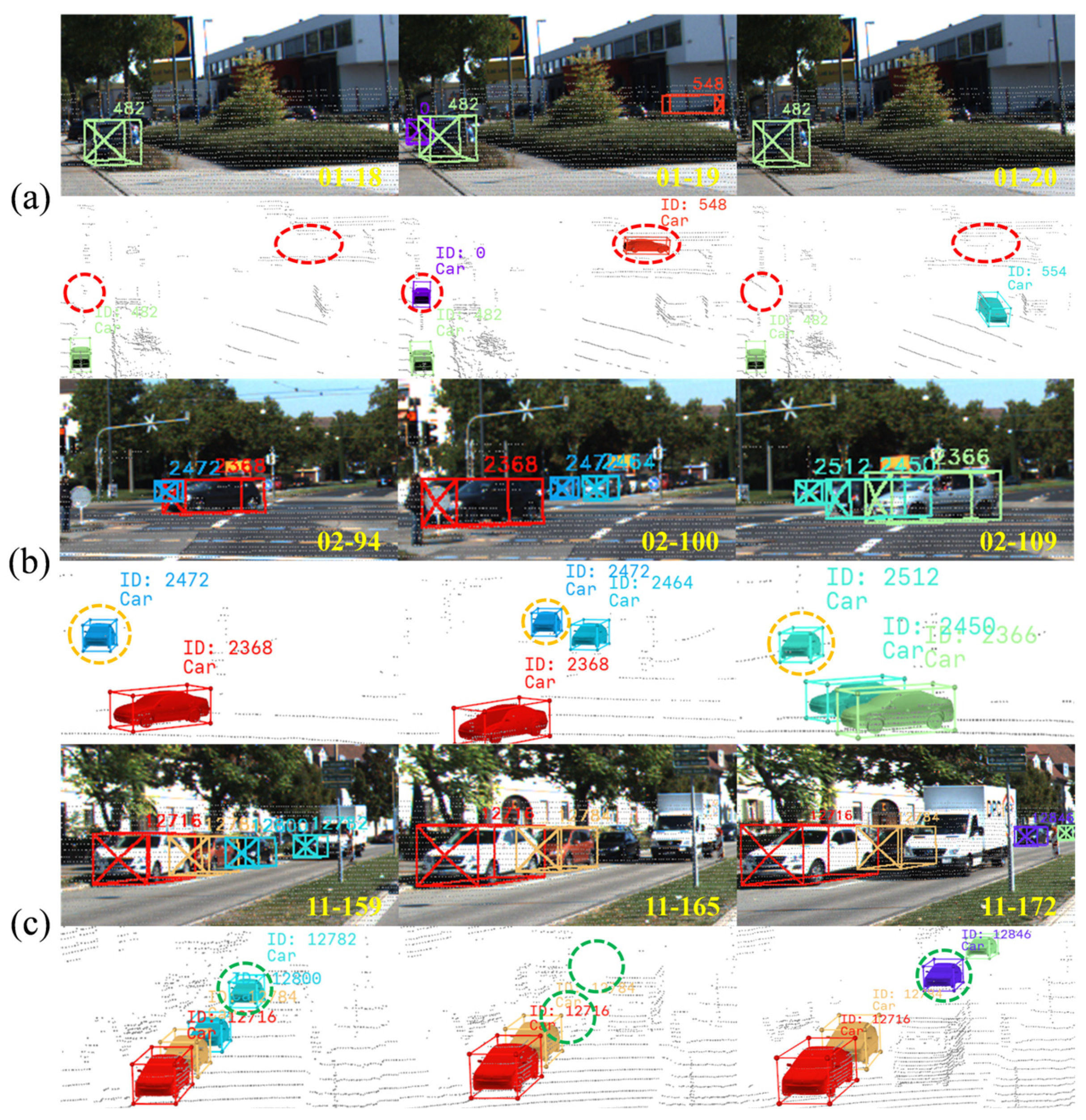

4.4. Visualization Analysis

To intuitively validate the effectiveness of the proposed method in addressing core challenges such as false positives, ghost trajectories, long-term occlusions, and identity switches, we conduct a systematic visual comparison of the tracking results between our method and the baseline model on the KITTI dataset. By selecting representative complex scenarios, the tracking outcomes are presented from both 2D image (left) and 3D point cloud (right) perspectives. The specific visualization results are shown in

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

As shown in the left subfigures of

Figure 7, the baseline model produces ghost trajectories in both frames 72 and 73 of the fifth scene. This occurs because it neglects the preprocessing of false positives, resulting in consecutive false detections that manifest as ghost trajectories. In contrast, the visualization results on the right demonstrate that the proposed method is completely free from ghost trajectories. This clearly indicates that our proposed CIGTS module effectively filters out false positives. Furthermore, the introduction of virtual trajectories optimizes the trajectory initialization strategy, collectively leading to effective suppression of ghost trajectories.

As shown in the left visualizations of

Figure 8, the object with ID 12782 in frame 153 undergoes an identity switch in frame 160, where its ID changes to 12746. Subsequently, the object with ID 12746 in frame 160 is reassigned a new ID, 12846, by frame 178. Finally, the object identified as 12746 in frame 178 experiences another identity switch in frame 184, acquiring ID 12874. In contrast, the right visualizations demonstrate that the proposed method exhibits no identity switches. This robustness is primarily attributed to the proposed AMSLA module. This module not only reduces the risk of incorrect matching through its adaptive matching space strategy but also incorporates more stable determining factors to construct a more discriminative association matrix, thereby further enhancing the accuracy of data association.

As shown in the left visualization of

Figure 9, the baseline model fails to distinguish between objects that have exited the scene and those that are temporarily occluded. It uniformly retains all unmatched trajectories for a fixed number of frames, leading to the excessive retention of an exited object (ID 9578) and causing duplicate matching in subsequent frames. In contrast, the right visualization demonstrates that the proposed method effectively avoids duplicate matching for exited objects. This capability primarily stems from the MFCTM module, which comprehensively evaluates object states through scene boundary awareness, motion trend analysis, and observation distance assessment. This integrated approach enables timely deletion of unmatched trajectories corresponding to exited objects while prioritizing the retention of those associated with temporarily occluded objects.

We also conduct a visual analysis of the pedestrian tracking results on the KITTI dataset to further validate the comprehensive performance of the proposed method on the pedestrian category. We selected typical complex scenarios containing multiple objects with severe occlusion, and performed a visual comparison between the tracking results of our method and the official KITTI ground truth. This comparison objectively demonstrates the effectiveness and stability of our method in pedestrian tracking tasks. As depicted in

Figure 10, the left side shows the visualization of the ground truth annotations, while the right side presents the visual output of the tracking results generated by our proposed method.

In

Figure 10, we select 40 consecutive frames of tracking results from high-complexity scenes for visualization. A horizontal analysis reveals that the proposed method produces no ghost trajectories, thereby validating the effectiveness of the CIGTS module. Furthermore, a longitudinal analysis across the 40-frame sequence demonstrates the complete absence of identity switches or incorrect associations, achieving continuous and accurate tracking of multiple objects. This confirms the efficacy of the AMSLA module. From a holistic perspective, the visualization results substantiate that the proposed 3D MOT method effectively addresses critical challenges including false positives, ghost trajectories, long-term occlusions, and identity switches, thereby enabling more stable and robust object tracking.