Assessment of Image Quality Performance of a Photon-Counting Computed Tomography Scanner Approved for Whole-Body Clinical Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PCCT Scanner Specification and Acquisition Protocols

2.2. Image Acquisitions

2.3. Image Quality Metrics and Analysis

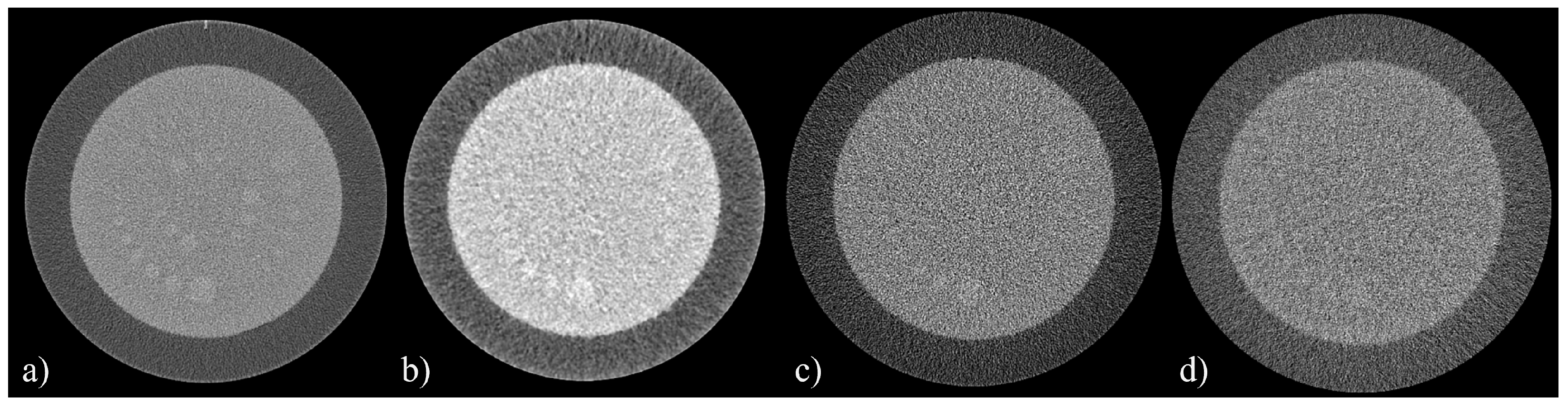

2.3.1. Uniformity Index (UI) and Integral Non-Uniformity (IN)

2.3.2. Slice Thickness

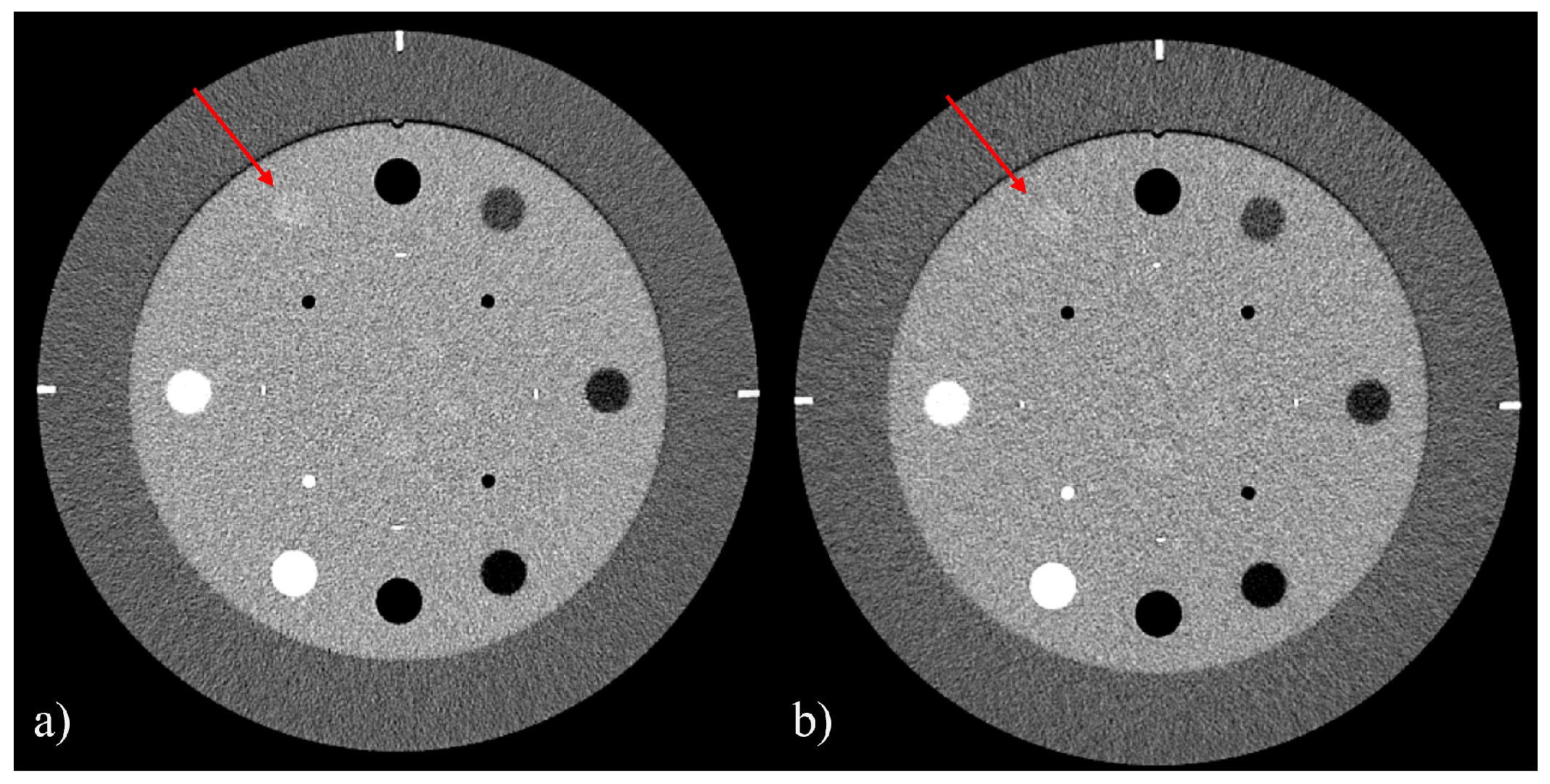

2.3.3. Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) and Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

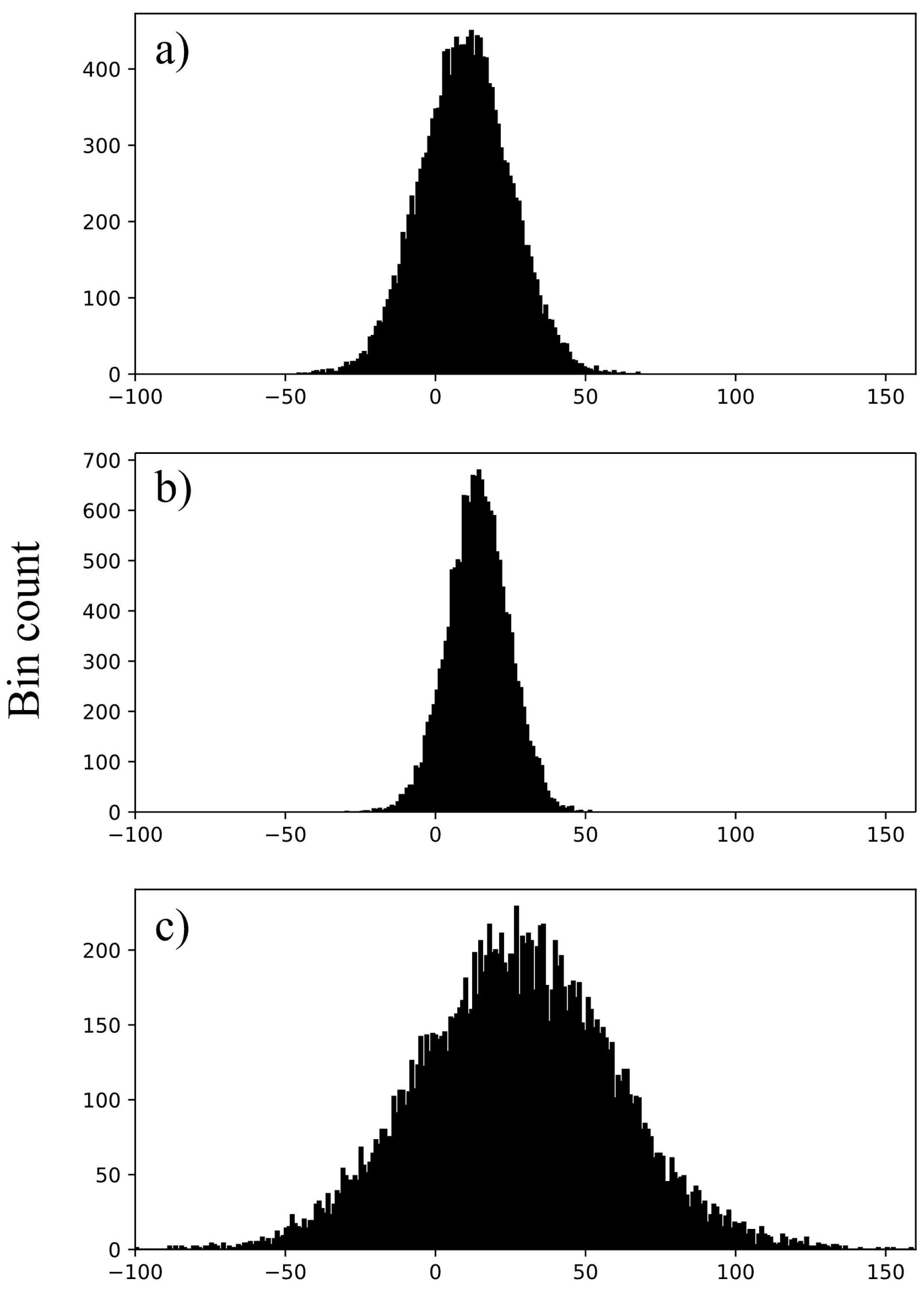

2.3.4. Image Histograms and CT Numbers

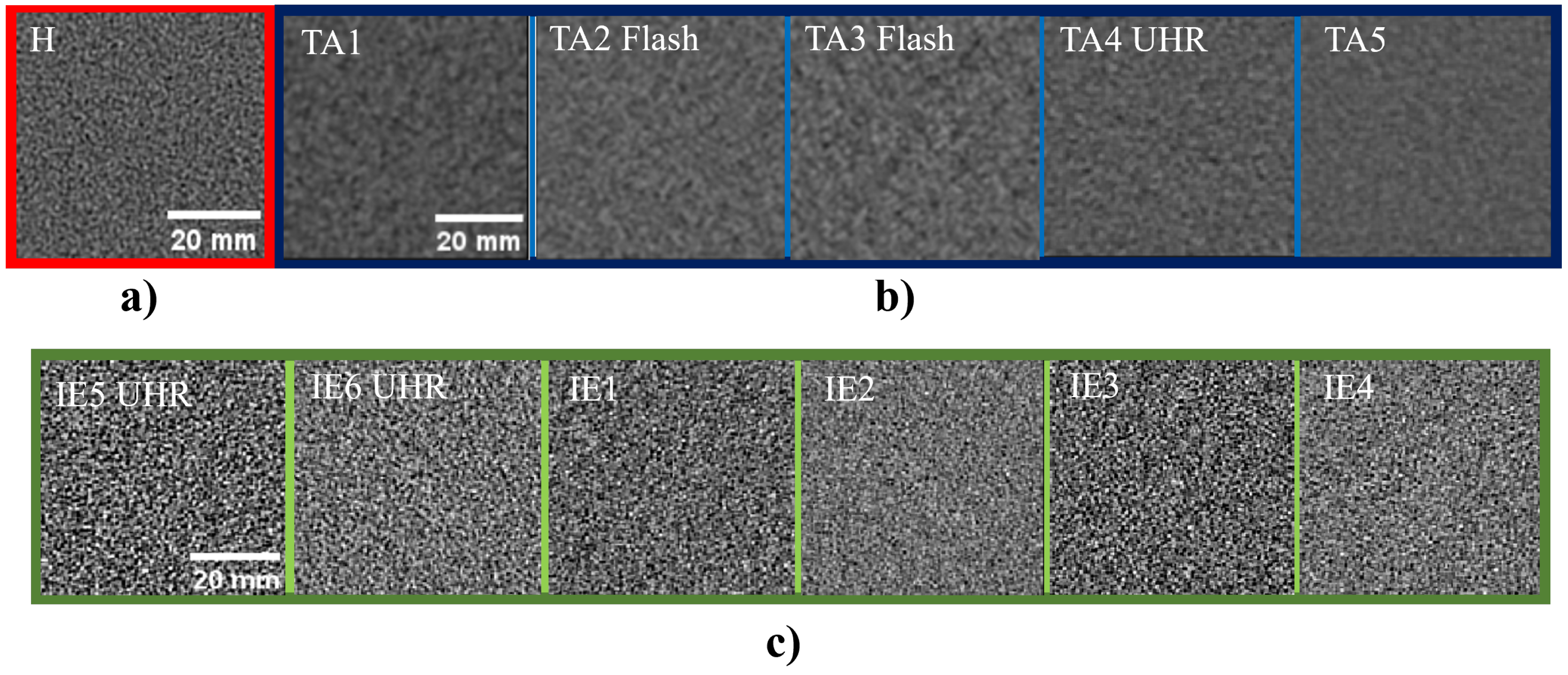

2.3.5. Noise Texture and Noise Power Spectrum

2.3.6. Spatial Resolution

2.3.7. Detectability Index

3. Results

3.1. Uniformity, Slice Thickness, and Low-Contrast Detail Visibility

3.2. Image Histograms

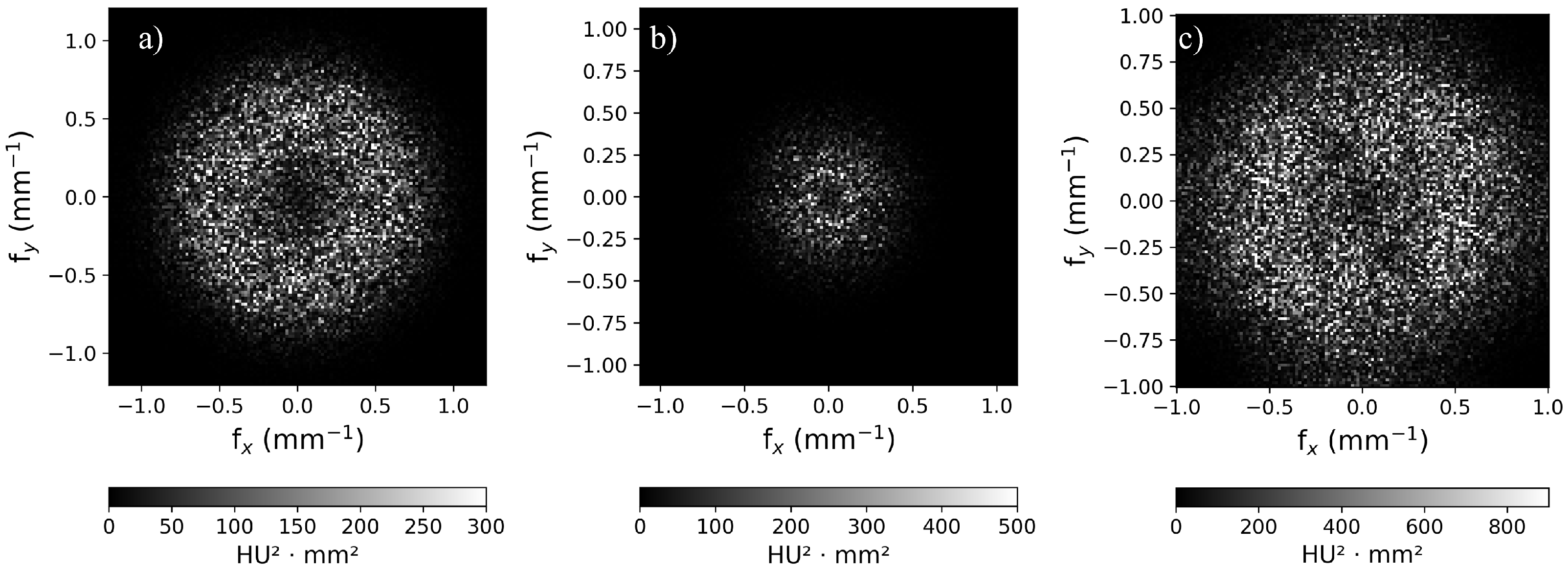

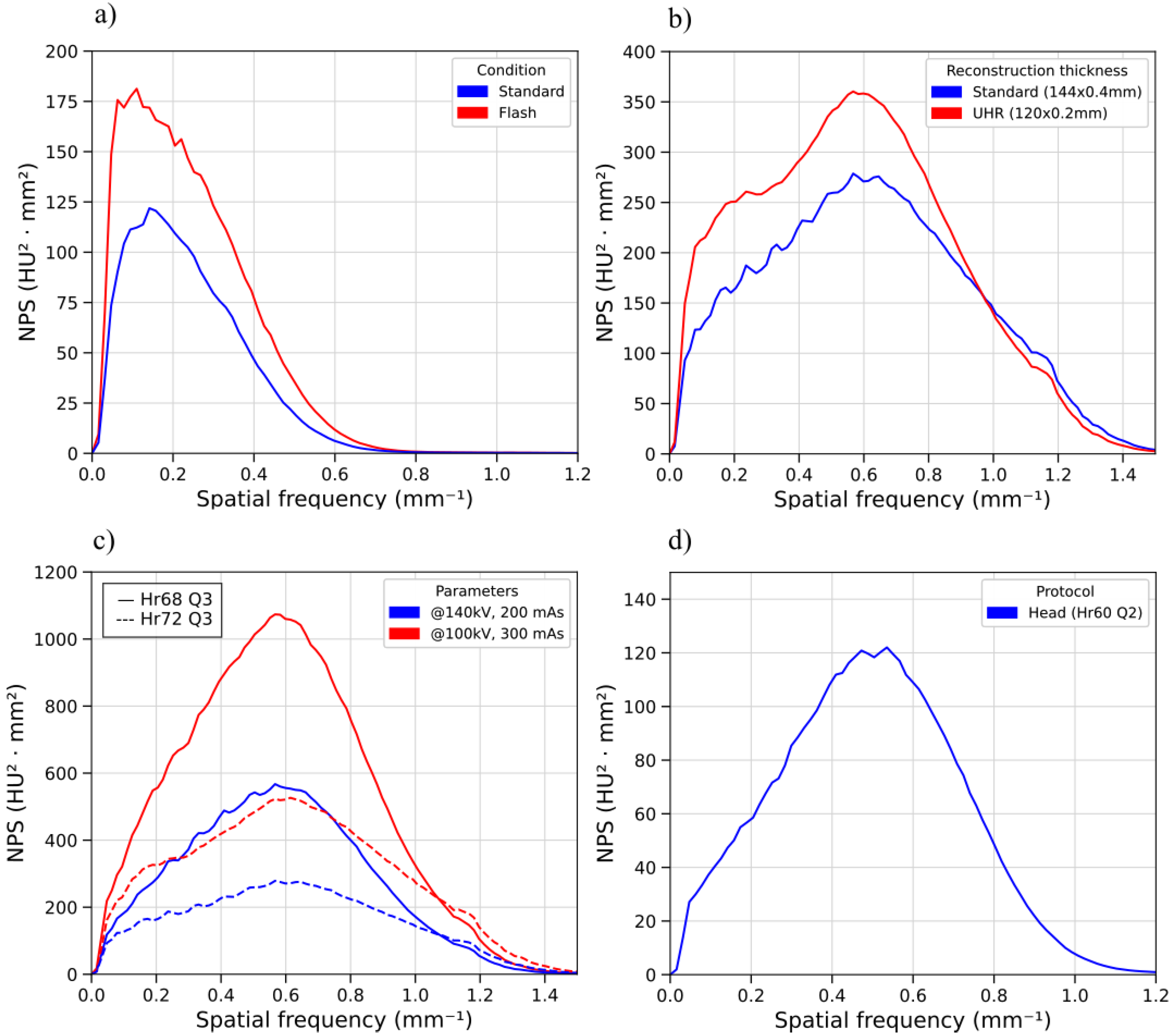

3.3. Noise Power Spectrum

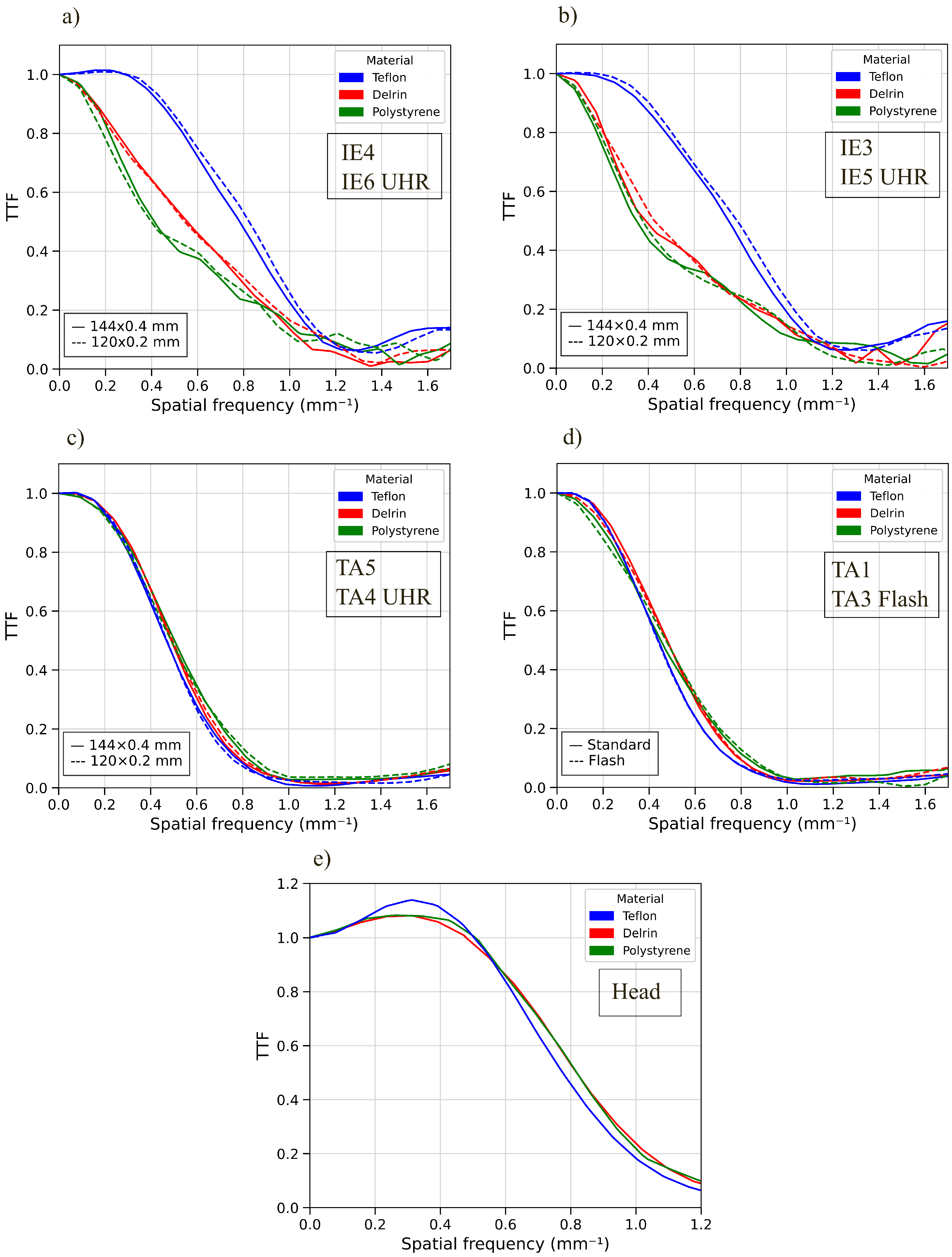

3.4. Target Transfer Function

3.5. Detectability Index

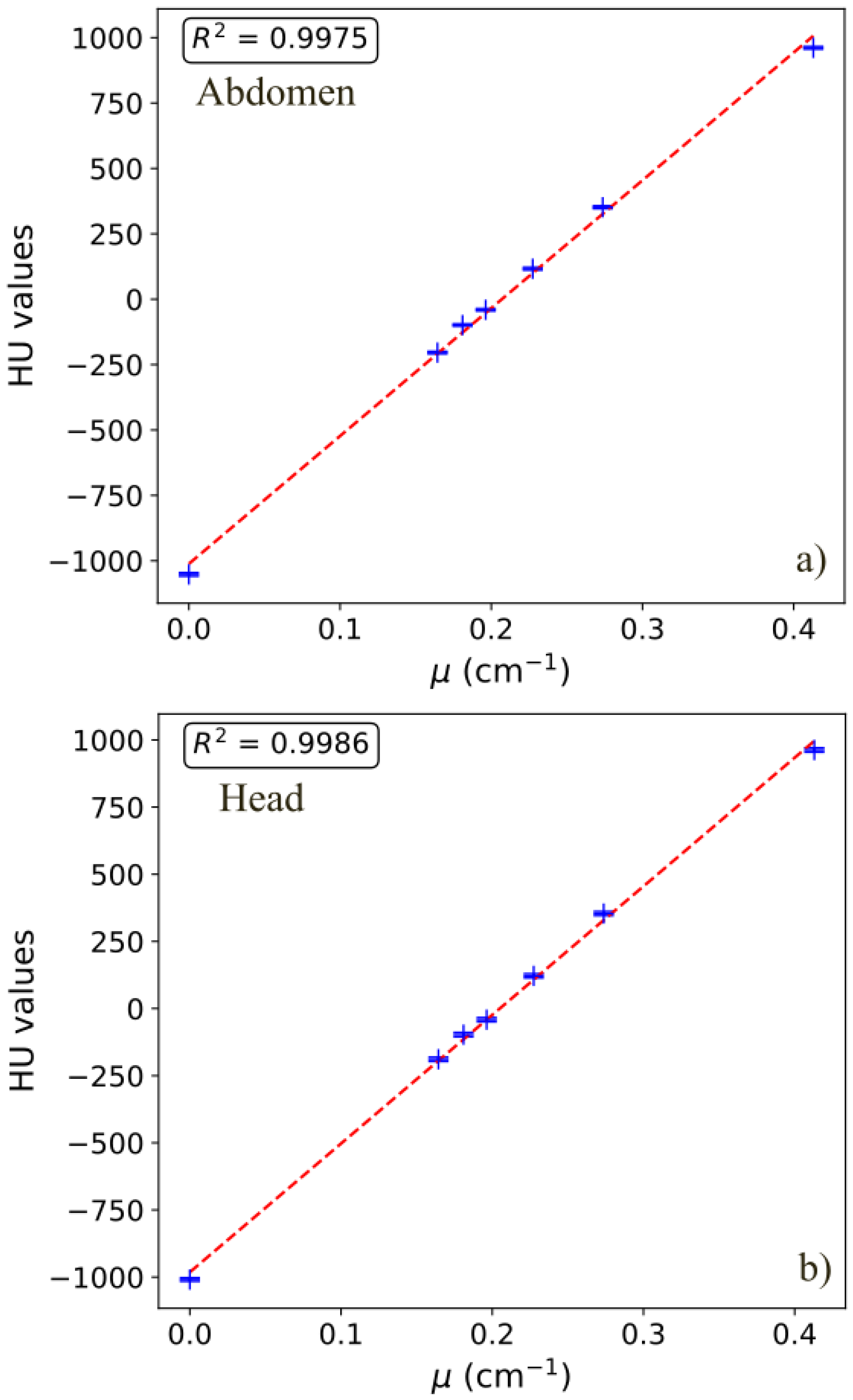

3.6. CT Numbers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Brenner, D.J. Computed Tomography—An Increasing Source of Radiation Exposure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2277–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booij, R.; Budde, R.P.J.; Dijkshoorn, M.L.; van Straten, M. Technological developments of X-ray computed tomography over half a century: User’s influence on protocol optimization. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020, 131, 109261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Bie, J.; van Straten, M.; Booij, R.; Bos, D.; Dijkshoorn, M.L.; Hirsch, A.; Sharma, S.P.; Oei, E.H.G.; Budde, R.P. Photon-counting CT: Review of initial clinical results. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 163, 110829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flohr, T.; Petersilka, M.; Henning, A.; Ulzheimer, S.; Ferda, J.; Schmidt, B. Photon-counting CT review. Phys. Med. 2020, 79, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielsson, M.; Persson, M.; Sjölin, M. Photon-counting X-ray detectors for CT. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021, 66, 03TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.G. Optimal image-based weighting for energy-resolved CT. Med. Phys. 2009, 36, 3018–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollough, C.H.; Rajendran, K.; Leng, S. Standardization and Quantitative Imaging With Photon-Counting Detector CT. Investig. Radiol. 2023, 58, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heismann, B.; Kreisler, B.; Fasbender, R. Photon counting CT versus energy-integrating CT: A comparative evaluation of advances in image resolution, noise, and dose efficiency. Med. Phys. 2025, 52, 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, F.R.; Sodickson, A.D.; Pickhardt, P.J.; Sahani, D.V.; Lev, M.H.; Gupta, R. Photon-Counting CT: Technology, Current and Potential Future Clinical Applications, and Overview of Approved Systems and Those in Various Stages of Research and Development. Radiology 2025, 314, e240662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treb, K.J.; Marsh, J.F.; Shanblatt, E.R.; Nowak, T.; Dunning, C.A.S.; Fung, G.S.K.; Schmidt, B.T.; McCollough, C.H.; Leng, S. Technical performance of dual-contrast-agent K-edge imaging with four energy thresholds on a commercial photon counting detector CT. Med. Phys. 2025, 52, e70063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbaski, S.; Bache, S.; Rajagopal, J.; Samei, E. Quantitative performance of photon-counting CT at low dose: Virtual monochromatic imaging and iodine quantification. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 5421–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawall, S.; Baader, E.; Trapp, P.; Kachelrieß, M. CT material decomposition with contrast agents: Single or multiple spectral photon-counting CT scans? A simulation study. Med. Phys. 2025, 52, 2167–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lell, M.; Kachelrieß, M. Computed Tomography 2.0: New Detector Technology, AI, and Other Developments. Investig. Radiol. 2023, 58, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkadhi, H.; Euler, A. The Future of Computed Tomography: Personalized, Functional, and Precise. Investig. Radiol. 2020, 55, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, V.; Steiding, C.; Heinemann, D.; Althoff, F.; Kolditz, D. Photon-Counting Breast CT: System Requirements, Development, Current Clinical Applications, and Possible Future Applications. In Clinical Applications of Spectral Photon Counting Computed Tomography Technology; Si-Mohamed, S.A., Iniewski, K.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, L.C.; Bode, M.; Zanderigo, E.; Wilpert, C.; Raaff, V.; Dethlefsen, E.; Wenkel, E.; Kuhl, C.K. Dedicated Photon-Counting CT for Detection and Classification of Microcalcifications: An Intraindividual Comparison with Digital Breast Tomosynthesis. Investig. Radiol. 2024, 59, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Park, J.; Kim, D.; Lee, D.; Lee, C.L.; Bechwati, I.; Wu, D.; Gupta, R.; Jung, J. The first mobile photon-counting detector CT: The human images and technical performance study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2023, 68, 095013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deleu, M.; Maurice, J.B.; Devos, L.; Remy, M.; Dubus, F. Image Quality Analysis of Photon-Counting CT Compared with Dual-Source CT: A Phantom Study for Chest CT Examinations. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schofield, R.; King, L.; Tayal, U.; Castellano, I.; Stirrup, J.; Pontana, F.; Earls, J.; Nicol, E. Image reconstruction: Part 1—Understanding filtered back projection, noise and image acquisition. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2020, 14, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataria, B.; Althén, J.N.; Smedby, Ö.; Persson, A.; Sökjer, H.; Sandborg, M. Assessment of image quality in abdominal CT: Potential dose reduction with model-based iterative reconstruction. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 2464–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, S.; Szilagyi, K.E.; Barca, P.; Bisello, F.; Spagnoli, L.; Domenichelli, S.; Strigari, L. A CT deep learning reconstruction algorithm: Image quality evaluation for brain protocol at decreasing dose indexes in comparison with FBP and statistical iterative reconstruction algorithms. Phys. Medica 2024, 119, 103319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, M.; Gemini, L.; D’Iglio, I.; Ugga, L.; Spadarella, G.; Cuocolo, R. Spectral Photon-Counting Computed Tomography: A Review on Technical Principles and Clinical Applications. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si-Mohamed, S.A.; Greffier, J.; Miailhes, J.; Boccalini, S.; Rodesch, P.A.; Vuillod, A.; Werf, N.v.; Dabli, D.; Racine, D.; Douek, P.; et al. Comparison of image quality between spectral photon-counting CT and dual-layer CT for the evaluation of lung nodules: A phantom study. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccalini, S.; Si-Mohamed, S.A.; Lacombe, H.; Diaw, A.; Varasteh, M.; Rodesch, P.A.; Villien, M.; Sigovan, M.; Dessouky, R.; Douek, P.C.; et al. First In-Human Results of Computed Tomography Angiography for Coronary Stent Assessment with a Spectral Photon Counting Computed Tomography. Investig. Radiol. 2022, 57, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliznakova, K.; Kolev, I.; Dukov, N.; Dimova, T.; Bliznakov, Z. Exploring the Potential of a Novel Iodine-Based Material as an Alternative Contrast Agent in X-ray Imaging Studies. Materials 2024, 17, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelgrim, G.J.; van Hamersvelt, R.W.; Willemink, M.J.; Schmidt, B.T.; Flohr, T.; Schilham, A.; Milles, J.; Oudkerk, M.; Leiner, T.; Vliegenthart, R. Accuracy of iodine quantification using dual energy CT in latest generation dual source and dual layer CT. Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 3904–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masturzo, L.; Barca, P.; De Masi, L.; Marfisi, D.; Traino, A.; Cademartiri, F.; Giannelli, M. Voxelwise characterization of noise for a clinical photon-counting CT scanner with a model-based iterative reconstruction algorithm. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2025, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffier, J.; Dabli, D.; Faby, S.; Pastor, M.; de Oliveira, F.; Croisille, C.; Erath, J.; Beregi, J.P. Potential dose reduction and image quality improvement in chest CT with a photon-counting CT compared to a new dual-source CT. Phys. Med. 2024, 127, 104844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsivais, H.; Liu, X.; Dong, F.; Jacobsen, M.C.; Rong, J.; Jensen, C.T.; Li, K. Three-dimensional noise characteristics of clinical photon counting detector CT. Med. Phys. 2025, 52, e70067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.F.; Klein, L.; Maier, J.; Rotkopf, L.T.; Schlemmer, H.P.; Schönberg, S.O.; Kachelrieß, M.; Sawall, S. Potential radiation dose reduction in clinical photon-counting CT by the small pixel effect: Ultra-high resolution (UHR) acquisitions reconstructed to standard resolution. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 34, 4484–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greffier, J.; Van Ngoc Ty, C.; Sammoud, S.; Croisille, C.; Beregi, J.P.; Dabli, D.; Fitton, I. Image quality and dose reduction with photon-counting detector CT: Comparison between ultra-high resolution mode and standard mode using a phantom study. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2025, 106, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samei, E.; Bakalyar, D.; Boedeker, K.L.; Brady, S.; Fan, J.; Leng, S.; Myers, K.J.; Popescu, L.M.; Giraldo, J.C.R.; Wang, J.; et al. Performance evaluation of computed tomography systems: Summary of AAPM Task Group 233. Med. Phys. 2019, 46, E735–E756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graafen, D.; Stoehr, F.; Halfmann, M.C.; Emrich, T.; Foerster, F.; Yang, Y.; Düber, C.; Müller, L.; Kloeckner, R. Quantum iterative reconstruction on a photon-counting detector CT improves the quality of hepatocellular carcinoma imaging. Cancer Imaging 2023, 23, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerns, J.R. Pylinac: Image analysis for routine quality assurance in radiotherapy. J. Open Source Softw. 2023, 8, 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wilson, J.; Samei, E. An automated software tool for task-based image quality assessment and matching in clinical CT using the TG-233 framework. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, E134. [Google Scholar]

- Elstrøm, U.V.; Muren, L.P.; Petersen, J.B.B.; Grau, C. Evaluation of image quality for different kV cone-beam CT acquisition and reconstruction methods in the head and neck region. Acta Oncol. 2011, 50, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissonnette, J.P.; Moseley, D.J.; Jaffray, D.A. A quality assurance program for image quality of cone-beam CT guidance in radiation therapy. Med. Phys. 2008, 35, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.M.; Boone, J.M. Tungsten anode spectral model using interpolating cubic splines: Unfiltered X-ray spectra from 20 kV to 640 kV. Med. Phys. 2014, 41, 042101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantler, C.T. Theoretical Form Factor, Attenuation, and Scattering Tabulation for Z = 1–92 from E = 1–10 eV to E = 0.4–1.0 MeV. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1995, 24, 71–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thor, D.; Titternes, R.; Poludniowski, G. Spatial resolution, noise properties, and detectability index of a deep learning reconstruction algorithm for dual-energy CT of the abdomen. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 2775–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, J.R.; Sahbaee, P.; Farhadi, F.; Solomon, J.B.; Ramirez-Giraldo, J.C.; Pritchard, W.F.; Wood, B.J.; Jones, E.C.; Samei, E. A clinically-driven task-based comparison of photon counting and conventional energy integrating CT for soft tissue, vascular, and high-resolution tasks. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 2020, 5, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Lane, J.I.; Carlson, M.L.; Bruesewitz, M.R.; Witte, R.J.; Koeller, K.K.; Eckel, L.J.; Carter, R.E.; McCollough, C.H.; Leng, S. Comparison of a Photon-Counting-Detector CT with an Energy-Integrating-Detector CT for Temporal Bone Imaging: A Cadaveric Study. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1733–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.; Murray, J.V.; Agarwal, A.K.; Sandhu, S.J.; Rhyner, P.A. Comprehensive Review of External and Middle Ear Anatomy on Photon-Counting CT. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2024, 45, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedeman, C.; Niu, C.; Li, M.; De Man, B.; Maltz, J.S.; Wang, G. Photon-counting CT using a Conditional Diffusion Model for Super-resolution and Texture-preservation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.16212. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, M.U.; Nizami, I.F.; Majid, M.; Ullah, F.; Hussain, I.; Chong, K.T. CN-BSRIQA: Cascaded network-blind super-resolution image quality assessment. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 91, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Vrbaški, S.; Bhattarai, M.; Abadi, E.; Longo, R.; Samei, E. A framework to model charge sharing and pulse pileup for virtual imaging trials of photon-counting CT. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 225001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, J.R.; Farhadi, F.; Richards, T.; Nikpanah, M.; Sahbaee, P.; Shanbhag, S.M.; Bandettini, W.P.; Saboury, B.; Malayeri, A.A.; Pritchard, W.F.; et al. Evaluation of coronary plaques and stents with conventional and photon-counting CT: Benefits of high-resolution photon-counting CT. Radiol. Cardiothorac. Imaging 2021, 3, e210102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| District (Abbreviation) | Protocol | kV | mAs | Slice Thickness (mm) | Collimation Width | Axial Pixel Size (mm) | Recon. Algorithm | Pitch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head (H) | H | 120 | 266 | 1.0 | 144 × 0.4 | 0.4135 × 0.4135 | Hr60 Q2 | 0.35 |

| Thorax/Abdomen (TA) | TA1 | 120 | 30 | 1.0 | 120 × 0.2 | 0.4271 × 0.4271 | Br40 Q4 | 0.85 |

| TA2 Flash | 140 | 30 | 1.0 | 144 × 0.4 | 0.4271 × 0.4271 | Br40 Q4 | 3.2 | |

| TA3 Flash | 120 | 30 | 1.0 | 144 × 0.4 | 0.4271 × 0.4271 | Br40 Q4 | 3.2 | |

| TA4 UHR | 140 | 100 | 0.2 | 120 × 0.2 | 0.4365 × 0.4365 | Br40 Q4 | 0.85 | |

| TA5 | 140 | 100 | 0.4 | 144 × 0.4 | 0.4365 × 0.4365 | Br40 Q4 | 0.85 | |

| Inner Ear (IE) | IE1 | 100 | 300 | 0.4 | 144 × 0.4 | 0.4199 × 0.4199 | Hr68 Q3 | 0.55 |

| IE2 | 140 | 200 | 0.4 | 144 × 0.4 | 0.4199 × 0.4199 | Hr68 Q3 | 0.55 | |

| IE3 | 100 | 300 | 0.4 | 144 × 0.4 | 0.4199 × 0.4199 | Hr72 Q3 | 0.55 | |

| IE4 | 140 | 200 | 0.4 | 144 × 0.4 | 0.4199 × 0.4199 | Hr72 Q3 | 0.55 | |

| IE5 UHR | 100 | 300 | 0.2 | 120 × 0.2 | 0.4199 × 0.4199 | Hr72 Q3 | 0.85 | |

| IE6 UHR | 140 | 200 | 0.2 | 120 × 0.2 | 0.4199 × 0.4199 | Hr72 Q3 | 0.85 |

| Protocol | UI | IN | Slice Thickness (mm) | CNR (1%, 15 mm) | SNR (1%, 15 mm) | CNR (1%, 5 mm) | SNR (1%, 5 mm) | CTDIvol (mGy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | 0.002 | 0.297 | 0.907 | 0.008 | 5.144 | 0.006 | 3.746 | 44.9 |

| TA1 | 0.199 | 0.001 | 1.293 | 0.018 | 7.367 | 0.009 | 10.762 | 2.4 |

| TA2 Flash | −0.099 | 0.001 | 1.208 | 0.014 | 10.714 | 0.012 | 9.060 | 3.4 |

| TA3 Flash | −0.099 | 0.001 | 1.010 | 0.013 | 8.822 | 0.023 | 9.809 | 2.4 |

| TA4 UHR | 0.076 | 0.062 | 0.646 | 0.014 | 8.113 | 0.009 | 6.394 | 11.6 |

| TA5 | 0.101 | 0.065 | 0.794 | 0.015 | 10.216 | −0.015 | 9.423 | 11.7 |

| IE1 | −0.076 | 0.066 | 0.690 | 0.002 | 1.227 | 1.089 | 5.1 | |

| IE2 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.791 | 0.002 | 2.366 | 1.861 | 13.3 | |

| IE3 | 0.059 | 0.055 | 0.754 | 0.002 | 1.717 | 1.451 | 5.1 | |

| IE4 | −0.049 | 0.052 | 0.617 | 0.002 | 2.952 | −0.001 | 2.647 | 13.3 |

| IE5 UHR | −0.032 | 0.074 | 0.498 | 0.001 | 1.736 | 0.002 | 1.932 | 5.1 |

| IE6 UHR | −0.053 | 0.063 | 0.462 | 0.002 | 2.563 | −0.001 | 2.348 | 13.5 |

| Protocol | Median (HU) | IQR (HU) | Kurtosis | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | 10 | 20 | 0.009 | −0.025 |

| TA1 | 4 | 10 | −0.035 | −0.007 |

| TA2 Flash | 13 | 11 | 0.126 | 0.022 |

| TA3 Flash | 14 | 12 | 0.067 | −0.035 |

| TA4 UHR | 10 | 11 | 0.008 | 0.037 |

| TA5 | 10 | 7 | 0.021 | −0.062 |

| IE1 | 18 | 69 | 0.034 | 0.012 |

| IE2 | 27 | 49 | −0.001 | 0.070 |

| IE3 | 17 | 54 | 0.070 | −0.021 |

| IE4 | 28 | 39 | 0.123 | −0.007 |

| IE5 UHR | 16 | 54 | 0.111 | 0.005 |

| IE6 UHR | 28 | 42 | 0.056 | 0.003 |

| Protocol | fpeak (mm−1) | faverage (mm−1) | Noise Magnitude (HU) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H | 0.50 | 0.49 | 23.4 |

| TA1 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 8.1 |

| TA2 Flash | 0.13 | 0.24 | 8.3 |

| TA3 Flash | 0.09 | 0.23 | 10.1 |

| TA4 UHR | 0.22 | 0.26 | 8.5 |

| TA5 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 5.7 |

| IE1 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 52.5 |

| IE2 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 38.1 |

| IE3 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 41.0 |

| IE4 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 30.8 |

| IE5 UHR | 0.58 | 0.56 | 42.3 |

| IE6 UHR | 0.58 | 0.57 | 32.5 |

| Protocol | Parameters | Acrylic (30) | Polystyrene (−120) | Air (−1065) | LDPE (−160) | PMP (−250) | Teflon (800) | Delrin (240) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head (H) | Hr60 (44.32 mGy), 1 mm | 11.38 | 56.25 | 467.54 | 80.92 | 121.37 | 372.59 | 106.23 |

| Inner Ear (IE) | UHR Hr72 (5.12 mGy) | 3.38 | 15.21 | 144.45 | 22.41 | 32.16 | 108.24 | 29.74 |

| UHR Hr72 (13.5 mGy) | 6.13 | 35.36 | 318.26 | 51.16 | 76.17 | 230.28 | 66.19 | |

| Hr72 (5.04 mGy), 0.4 mm | 3.93 | 29.07 | 265.10 | 42.45 | 62.62 | 200.78 | 53.22 | |

| Hr72 (13.3 mGy), 0.4 mm | 10.59 | 44.06 | 412.75 | 65.58 | 100.39 | 294.66 | 88.62 | |

| Thorax/Abdomen (TA) | Br40 (2.36 mGy), 1 mm | 4.74 | 35.29 | 258.53 | 51.39 | 72.00 | 205.56 | 65.80 |

| Br40 (3.44 mGy) Flash, 1 mm | 5.06 | 41.12 | 322.64 | 60.77 | 88.84 | 261.07 | 73.76 | |

| Br40 (2.36 mGy) Flash, 1 mm | 4.25 | 28.24 | 220.34 | 41.14 | 59.75 | 163.62 | 52.30 | |

| UHR Br40 (11.6 mGy) | 6.66 | 39.90 | 318.37 | 57.59 | 84.57 | 248.73 | 76.52 | |

| Br40 (11.6 mGy), 0.4 mm | 10.62 | 59.29 | 457.19 | 83.97 | 124.45 | 360.21 | 108.81 |

| Protocol | Polystyrene | Delrin | Teflon | Air | Acrylic | PMP | LDPE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | −40.6 | 350.8 | 955.5 | −1008.0 | 119.7 | −188.4 | −97.6 | 0.9986 |

| TA1 | −51.0 | 353.3 | 981.6 | −1032.5 | 116.4 | −201.9 | −110.5 | 0.9988 |

| TA2 Flash | −51.8 | 363.0 | 979.7 | −1040.1 | 111.5 | −193.3 | −110.2 | 0.9980 |

| TA3 Flash | −36.6 | 353.8 | 964.5 | −1055.5 | 122.1 | −198.8 | −97.0 | 0.9975 |

| TA4 UHR | −43.3 | 359.6 | 980.5 | −1033.9 | 120.8 | −194.4 | −102.8 | 0.9986 |

| TA5 | −43.4 | 360.6 | 982.0 | −1034.4 | 122.1 | −195.1 | −103.0 | 0.9984 |

| IE1 | −27.6 | 349.8 | 919.0 | −985.1 | 126.6 | −173.9 | −82.6 | 0.9972 |

| IE2 | −15.8 | 358.3 | 900.9 | −983.8 | 134.3 | −163.6 | −71.5 | 0.9951 |

| IE3 | −32.2 | 341.9 | 909.0 | −978.7 | 120.0 | −174.7 | −85.6 | 0.9972 |

| IE4 | −15.8 | 355.1 | 899.3 | −982.4 | 133.4 | −161.2 | −70.1 | 0.9953 |

| IE5 UHR | −29.2 | 343.8 | 910.1 | −967.7 | 121.9 | −169.3 | −83.9 | 0.9974 |

| IE6 UHR | −14.8 | 350.3 | 891.1 | −970.0 | 134.2 | −159.9 | −69.5 | 0.9951 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maddaloni, F.S.; Sarno, A.; Loria, A.; Piai, A.; Lenardi, C.; Esposito, A.; del Vecchio, A. Assessment of Image Quality Performance of a Photon-Counting Computed Tomography Scanner Approved for Whole-Body Clinical Applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 7338. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237338

Maddaloni FS, Sarno A, Loria A, Piai A, Lenardi C, Esposito A, del Vecchio A. Assessment of Image Quality Performance of a Photon-Counting Computed Tomography Scanner Approved for Whole-Body Clinical Applications. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7338. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237338

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaddaloni, Francesca Saveria, Antonio Sarno, Alessandro Loria, Anna Piai, Cristina Lenardi, Antonio Esposito, and Antonella del Vecchio. 2025. "Assessment of Image Quality Performance of a Photon-Counting Computed Tomography Scanner Approved for Whole-Body Clinical Applications" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7338. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237338

APA StyleMaddaloni, F. S., Sarno, A., Loria, A., Piai, A., Lenardi, C., Esposito, A., & del Vecchio, A. (2025). Assessment of Image Quality Performance of a Photon-Counting Computed Tomography Scanner Approved for Whole-Body Clinical Applications. Sensors, 25(23), 7338. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237338