CDFFusion: A Color-Deviation-Free Fusion Network for Nighttime Infrared and Visible Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

- It proposes CDFFusion, a two-stage network for joint low-light image enhancement and image fusion, which can mitigate visual overexposure, image blocking artifacts and color deviation;

- A brightness enhancement formula without color deviation is proposed, which processes the three components (Y, Cb, Cr) simultaneously, and the processed results have the smallest color deviation.

2. Related Work

3. Methods

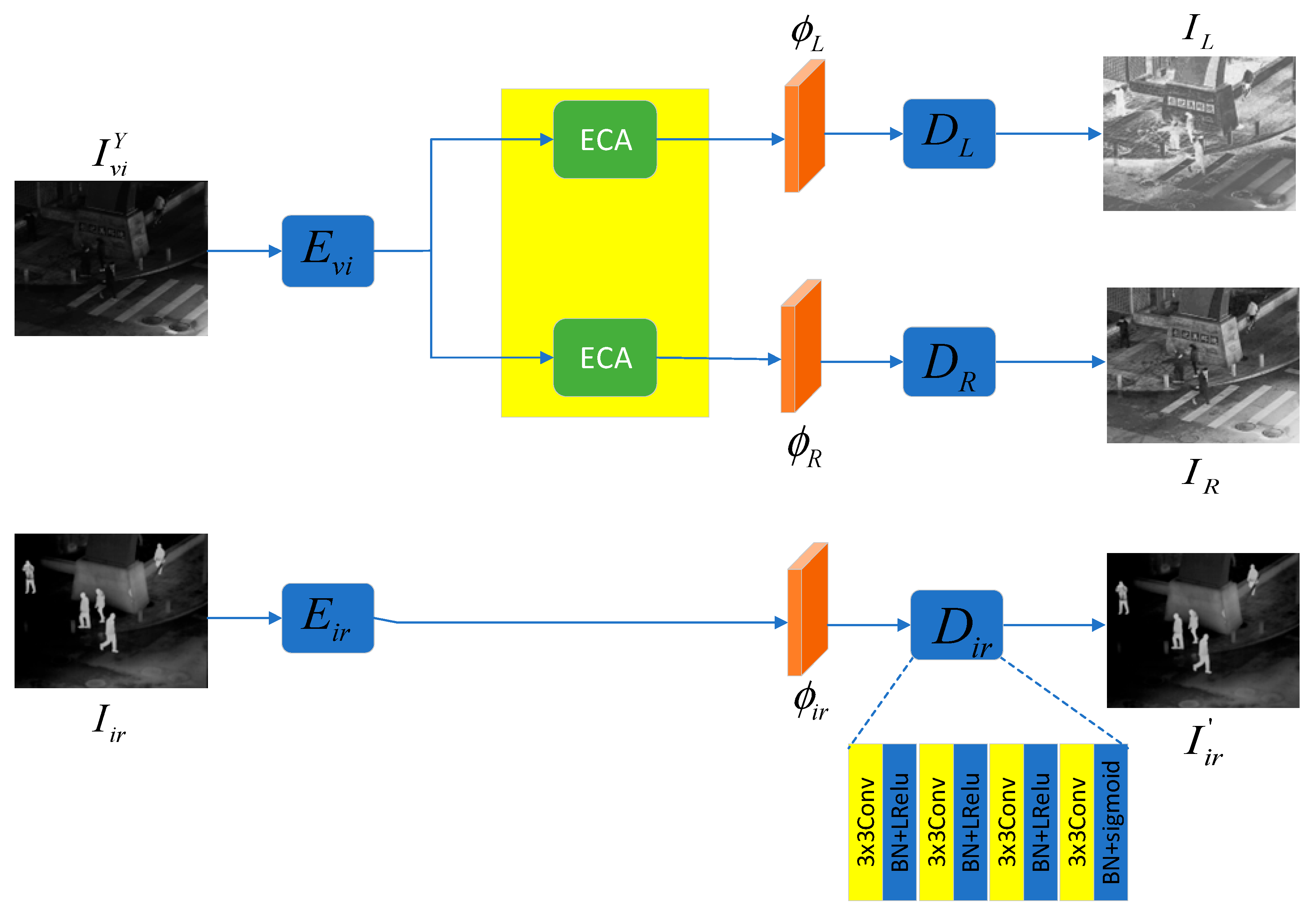

3.1. Overall Framework

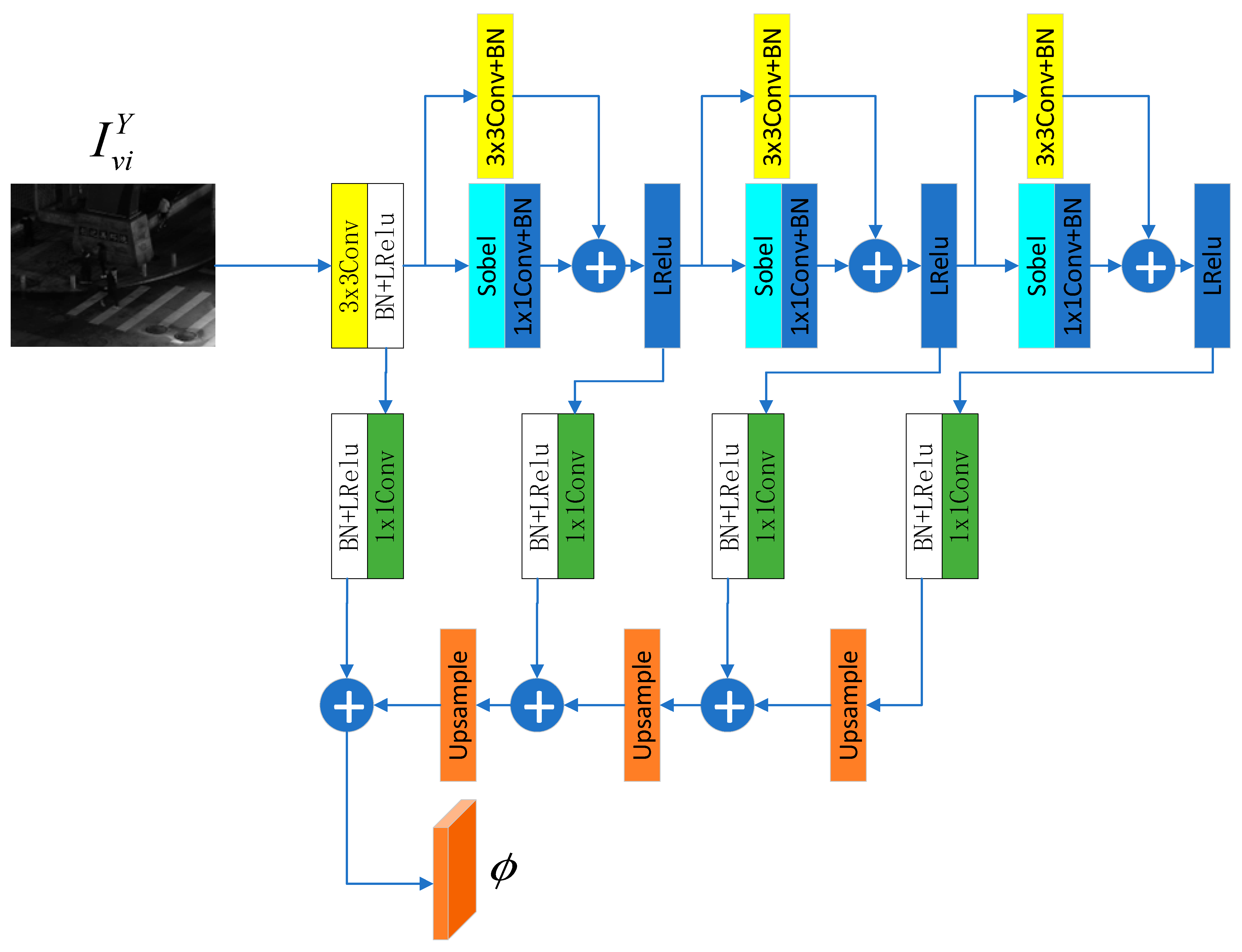

3.2. Reflectance–Illumination Decomposition Network (RID-Net)

3.3. Fusion Network

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Configuration

4.2. Results and Analysis

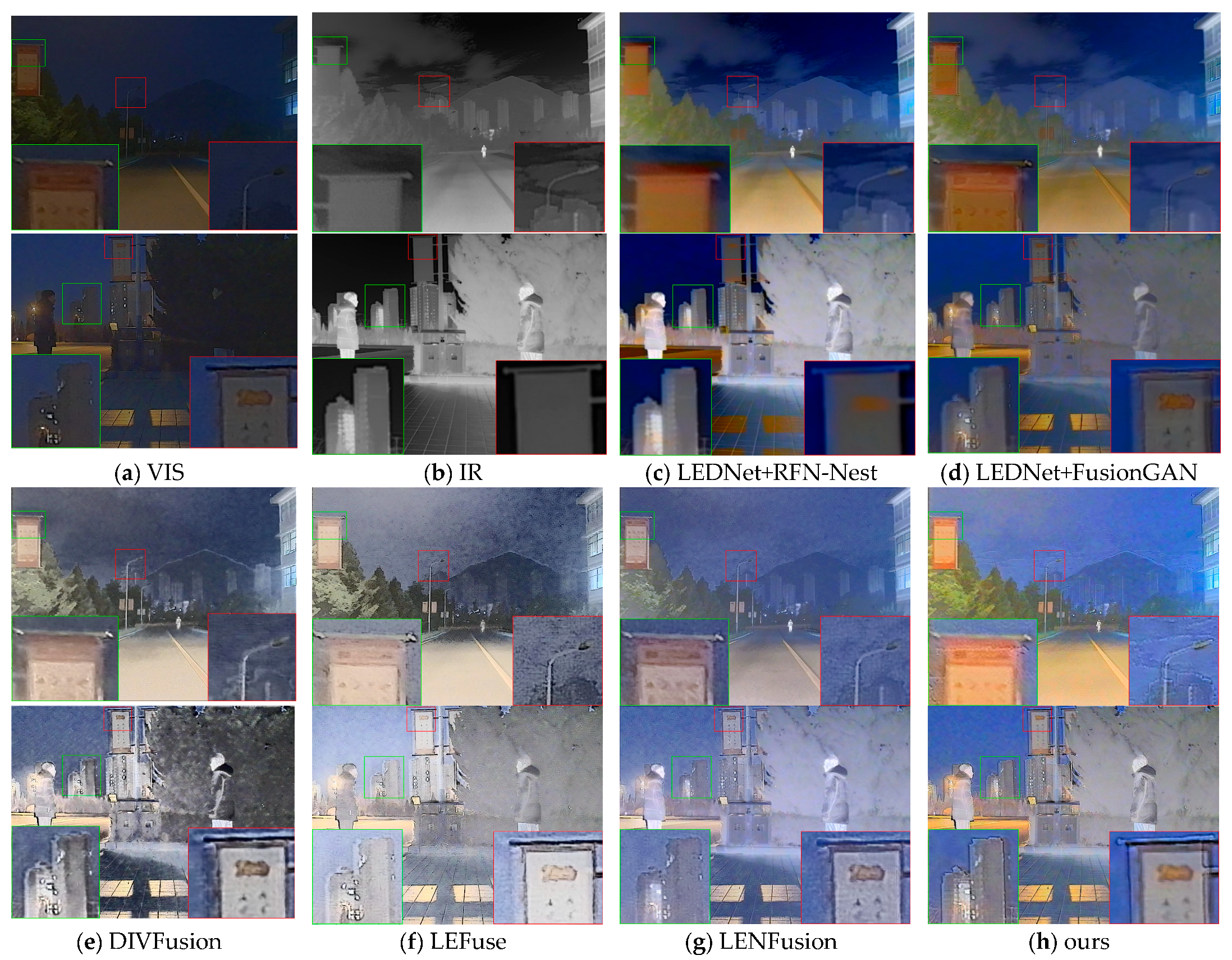

4.2.1. Qualitative Comparison

4.2.2. Quantitative Comparison

4.3. Generalization Experiment

4.3.1. Qualitative Comparison

4.3.2. Quantitative Analysis

4.4. Ablation Experiment

4.4.1. Qualitative Comparison

4.4.2. Quantitative Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A

- Substituting and into the above equation, we have or , where .

- First, we consider

- 2.

- Second, we consider

References

- Zhou, S.; Li, C.; Change Loy, C. LEDNet: Joint Low-Light Enhancement and Deblurring in the Dark. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Tang, L.; Xu, M.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, G. STDFusionNet: An infrared and visible image fusion network based on salient target detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, J. SDNet: A Versatile Squeeze-and-Decomposition Network for Real-Time Image Fusion. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 2761–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ma, J.; Jiang, J.; Guo, X.; Ling, H. U2Fusion: A Unified Unsupervised Image Fusion Network. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 502–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Bai, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Lin, Z.; Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. CDDFuse: Correlation-Driven Dual-Branch Feature Decomposition for Multi-Modality Image Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Ma, J. PIAFusion: A progressive infrared and visible image fusion network based on illumination aware. Inf. Fusion 2022, 83, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, X.J. DenseFuse: A fusion approach to infrared and visible images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2019, 28, 2614–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wu, X.J.; Durrani, T. NestFuse: An Infrared and Visible Image Fusion Architecture Based on Nest Connection and Spatial/Channel Attention Models. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 9645–9656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, X.-J.; Kittler, J. RFN-Nest: An end-to-end residual fusion network for infrared and visible images. Inf. Fusion 2021, 73, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J. Classification saliency-based rule for visible and infrared image fusion. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 2021, 7, 824–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yu, W.; Liang, P.; Li, C.; Jiang, J. FusionGAN: A generative adversarial network for infrared and visible image fusion. Inf. Fusion 2019, 48, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, H.; Shao, Z.; Liang, P.; Xu, H. GANMcC: A Generative Adversarial Network With Multiclassification Constraints for Infrared and Visible Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Ling, H. Unified gradientand intensity-discriminator generative adversarial network for image fusion. Inf. Fusion 2022, 88, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liang, P.; Yu, W.; Jiang, J.; Ma, J. Learning a generative model for fusing infrared and visible images via conditional generative adversarial network with dual discriminators. In Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; pp. 3954–3960. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, H.; Gong, M.; Ma, J. DIVFusion: Darkness-free infrared and visible image fusion. Inf. Fusion 2023, 91, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, W.; Tian, X.; Ma, J. LENFusion: A Joint Low-Light Enhancement and Fusion Network for Nighttime Infrared and Visible Image Fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Huang, H.; Liu, X.; Mo, H.; Zhao, X.; Wu, S. LEFuse: Joint low-light enhancement and image fusion for nighttime infrared and visible images. Neurocomputing 2025, 626, 129592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU-R BT.601-7(03/2011); Studio Encoding Parameters of Digital Television for Standard 4:3 and Wide-Screen 16:9 Aspect Ratios. ITU: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Jia, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, M.; Tang, W.; Zhou, W. LLVIP: A Visible-infrared Paired Dataset for Low-light Vision. In Proceedings of the 18th IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, ICCVW, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Huang, Z.; Wu, G.; Liu, R.; Zhong, W.; Luo, Z. Target-aware Dual Adversarial Learning and a Multi-scenario Multi-Modality Benchmark to Fuse Infrared and Visible for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

| SF | CC | Nabf | Qabf | SCD | MS-SSIM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFN-Nest | 5.0344 | 0.5824 | 0.0099 | 0.3332 | 1.0923 | 0.7730 | 0.2501 |

| FusionGAN | 6.7466 | 0.6479 | 0.0124 | 0.2788 | 0.9159 | 0.8188 | 0.1559 |

| DIVFusion | 14.7371 | 0.6922 | 0.1364 | 0.3823 | 1.5373 | 0.7973 | 0.3388 |

| LEFuse | 24.0328 | 0.6087 | 0.1856 | 0.3006 | 1.2262 | 0.7027 | 0.3141 |

| LENFusion | 21.4990 | 0.5928 | 0.1969 | 0.3534 | 1.0440 | 0.7236 | 0.3350 |

| Ours | 17.6531 | 0.6619 | 0.1075 | 0.4279 | 1.2760 | 0.8335 | 0.0706 |

| SF | CC | Nabf | Qabf | SCD | MS-SSIM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFN-Nest | 4.1495 | 0.6260 | 0.0039 | 0.3133 | 0.9690 | 0.8565 | 0.1968 |

| FusionGAN | 6.2380 | 0.6579 | 0.0143 | 0.2770 | 0.7082 | 0.8788 | 0.1399 |

| DIVFusion | 14.4927 | 0.7360 | 0.1525 | 0.3684 | 1.6140 | 0.8276 | 0.0785 |

| LEFuse | 20.6205 | 0.6623 | 0.2416 | 0.2504 | 1.2501 | 0.7236 | 0.1190 |

| LENFusion | 14.6193 | 0.6640 | 0.1402 | 0.3637 | 0.9860 | 0.8011 | 0.0883 |

| ours | 16.4501 | 0.6879 | 0.1251 | 0.3694 | 1.0070 | 0.8416 | 0.0269 |

| SF | CC | Nabf | Qabf | SCD | MS-SSIM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/O | 17.7592 | 0.209 | 0.0868 | 0.4103 | 0.1861 | 0.6925 | 0.0750 |

| W/O | 15.3465 | 0.6607 | 0.0957 | 0.4169 | 1.242 | 0.8699 | 0.0838 |

| W/O E | 15.5647 | 0.5085 | 0.1080 | 0.2774 | 0.5027 | 0.7765 | 0.0855 |

| ours | 17.6531 | 0.6619 | 0.1075 | 0.4279 | 1.276 | 0.8335 | 0.0706 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhai, S.; Tong, X.; Zhu, R. CDFFusion: A Color-Deviation-Free Fusion Network for Nighttime Infrared and Visible Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 7337. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237337

Chen H, Zhang T, Zhai S, Tong X, Zhu R. CDFFusion: A Color-Deviation-Free Fusion Network for Nighttime Infrared and Visible Images. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7337. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237337

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Hao, Tinghua Zhang, Shijie Zhai, Xiaoyun Tong, and Rui Zhu. 2025. "CDFFusion: A Color-Deviation-Free Fusion Network for Nighttime Infrared and Visible Images" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7337. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237337

APA StyleChen, H., Zhang, T., Zhai, S., Tong, X., & Zhu, R. (2025). CDFFusion: A Color-Deviation-Free Fusion Network for Nighttime Infrared and Visible Images. Sensors, 25(23), 7337. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237337