Research on the Prediction of Driver Fatigue Degree Based on EEG Signals

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The CTL-ResFNet hybrid neural network is proposed, which for the first time organically integrates the local feature extraction capability of CNN, the global dependency modeling of Transformer, and the temporal dynamic capturing of LSTM through residual connections, addressing the representational limitations of traditional single models in cross-modal EEG-fatigue temporal prediction. Experiments demonstrate that this architecture significantly outperforms baseline models in both leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) and transfer learning scenarios, providing a new paradigm for physiological signal temporal prediction.

- (2)

- Through LOOCV, it was discovered that the spatiotemporal coupling of EEG differential entropy features and PERCLOS can improve prediction accuracy, revealing the complementary enhancement effect of physiological signals on subjective fatigue labels. Further research revealed that in LOOCV, the predictive performance of the band energy ratio significantly outperforms comparative features such as differential entropy and wavelet entropy, demonstrating its superior zero-shot cross-subject generalization ability and stronger robustness to individual differences.

- (3)

- To validate the small-sample individual adaptation capability of CTL-ResFNet, this study established a pretraining–finetuning experimental framework. The results demonstrate that differential entropy features exhibit optimal performance in transfer learning scenarios. This finding provides methodological guidance for optimizing feature selection in practical fatigue monitoring system applications.

2. Related Work

3. Methods

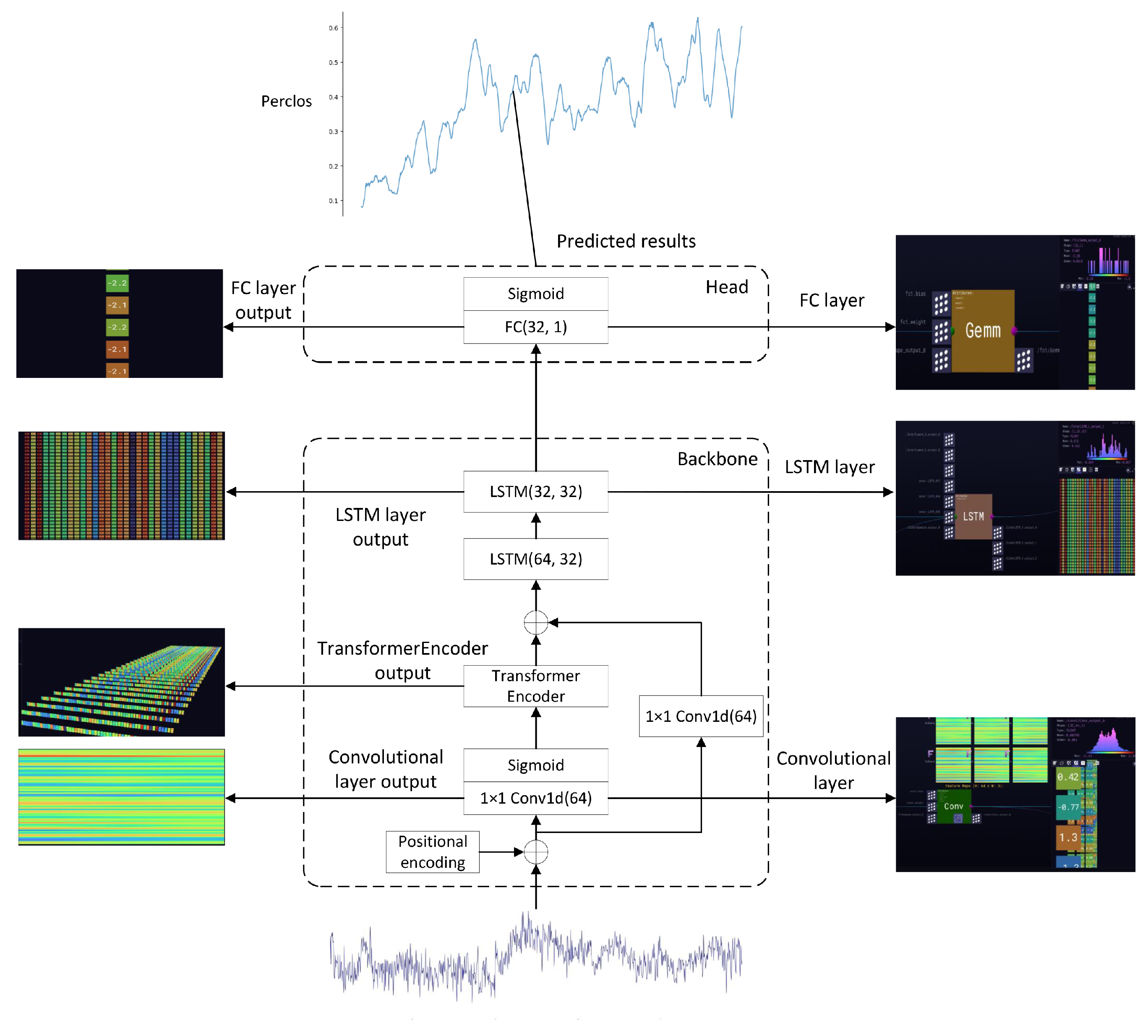

3.1. Overall Architecture

3.2. Position Encoding and Activation Function

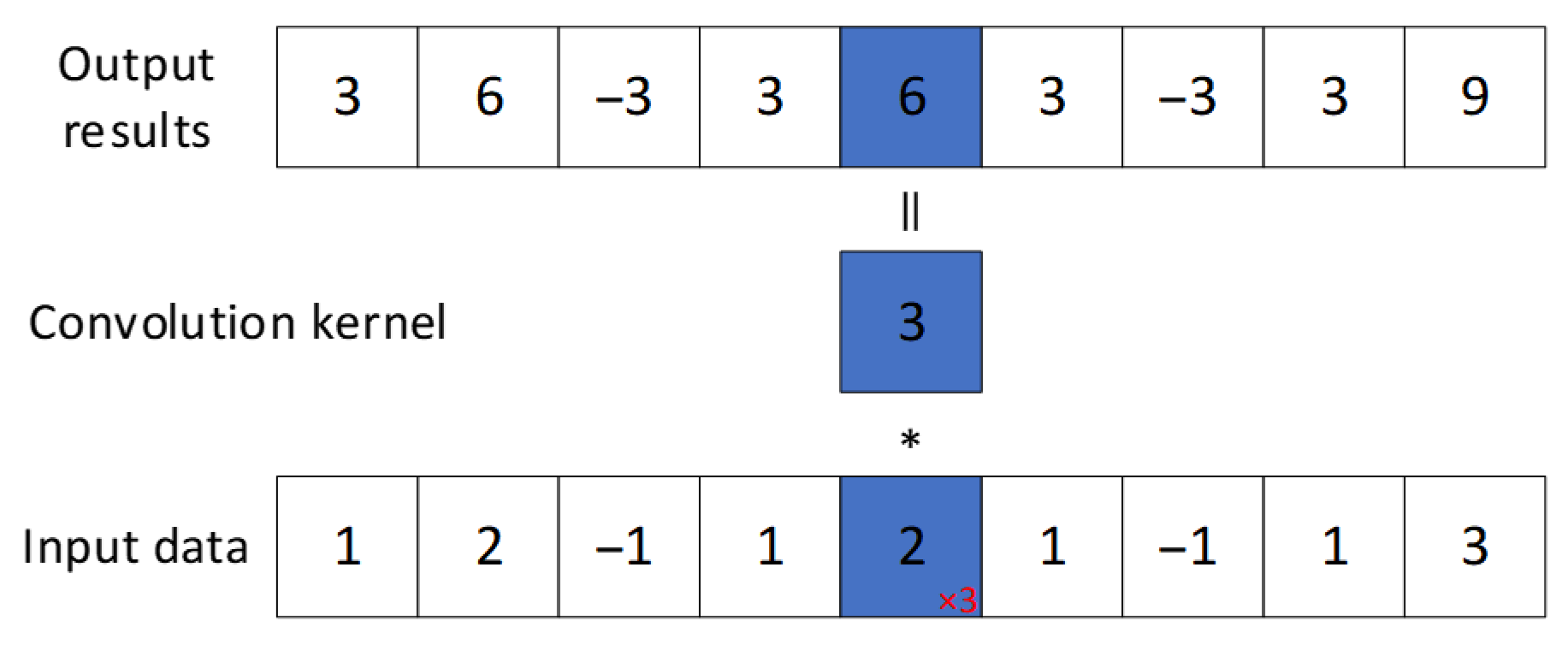

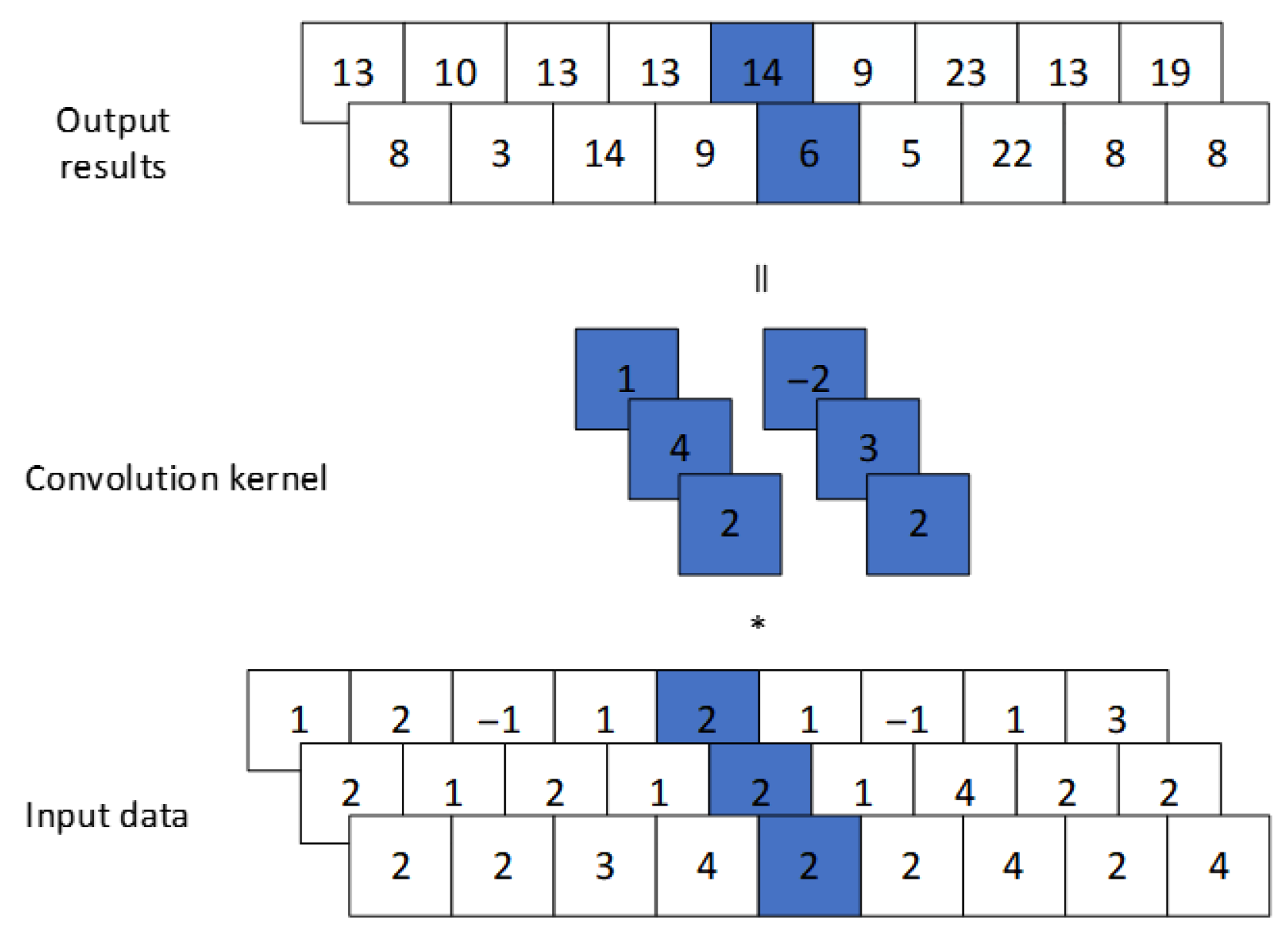

3.3. CNN Module

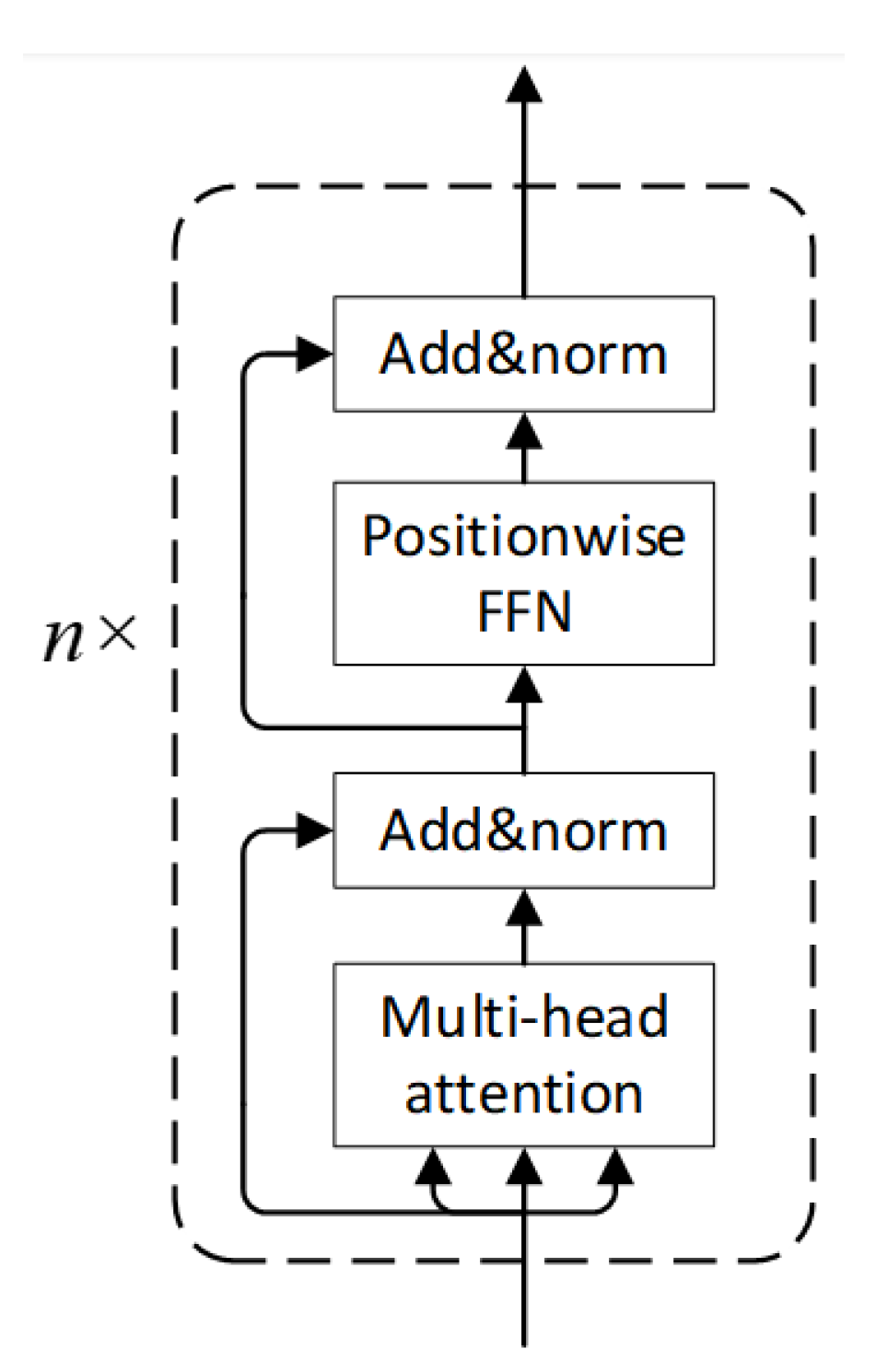

3.4. Transformer Encoder Module

3.5. LSTM Module

3.6. Regression Prediction Head

4. Experiments

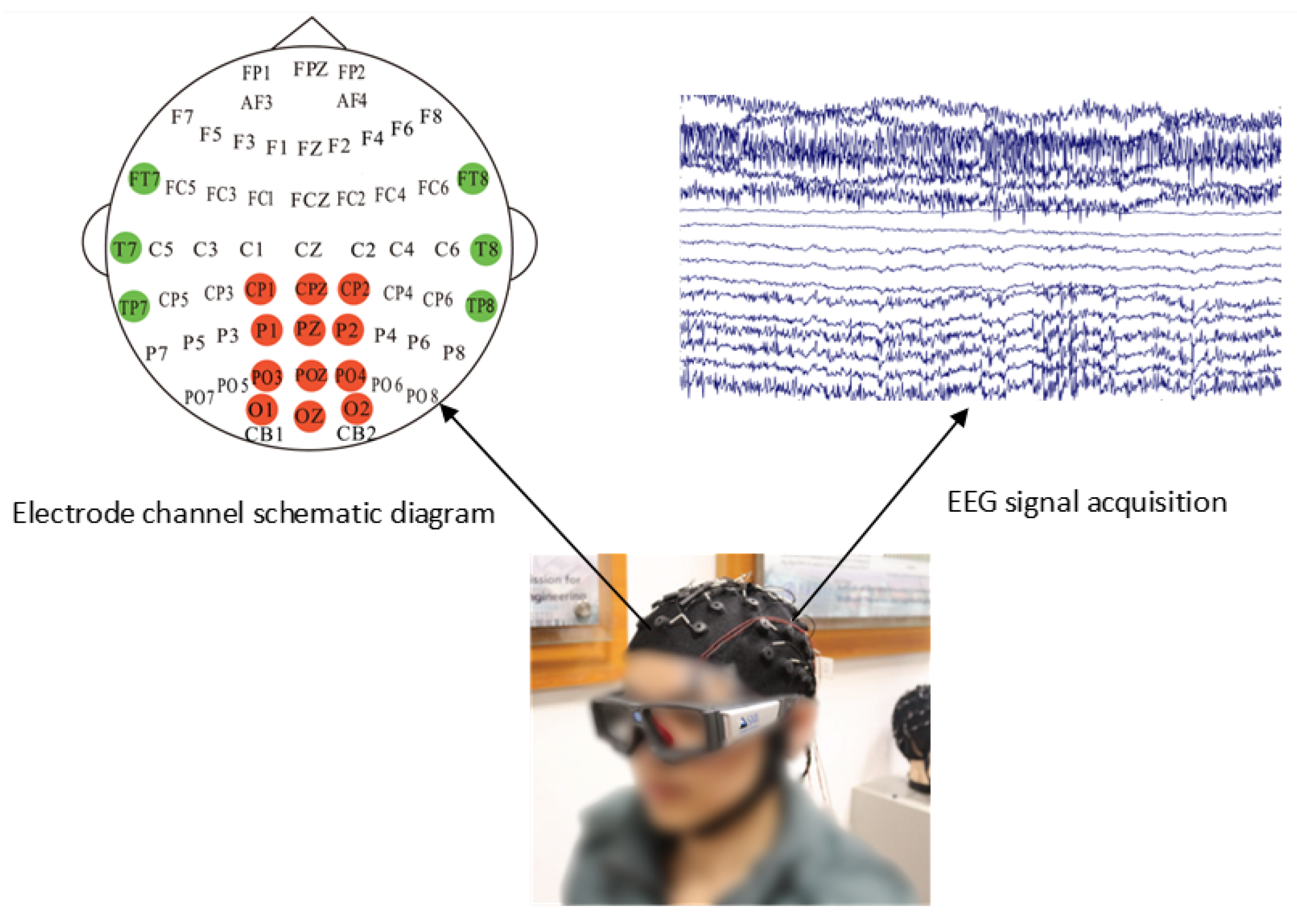

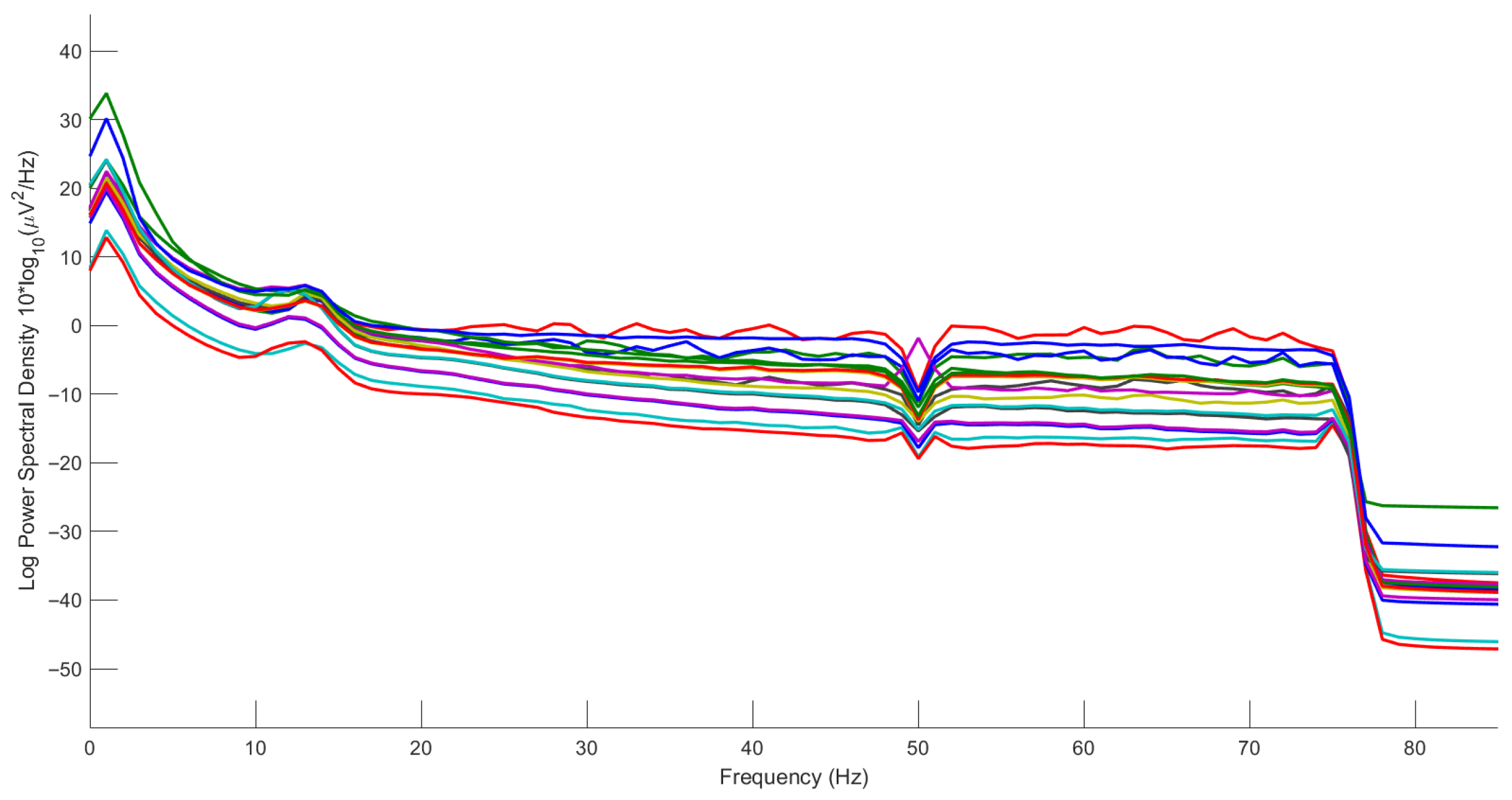

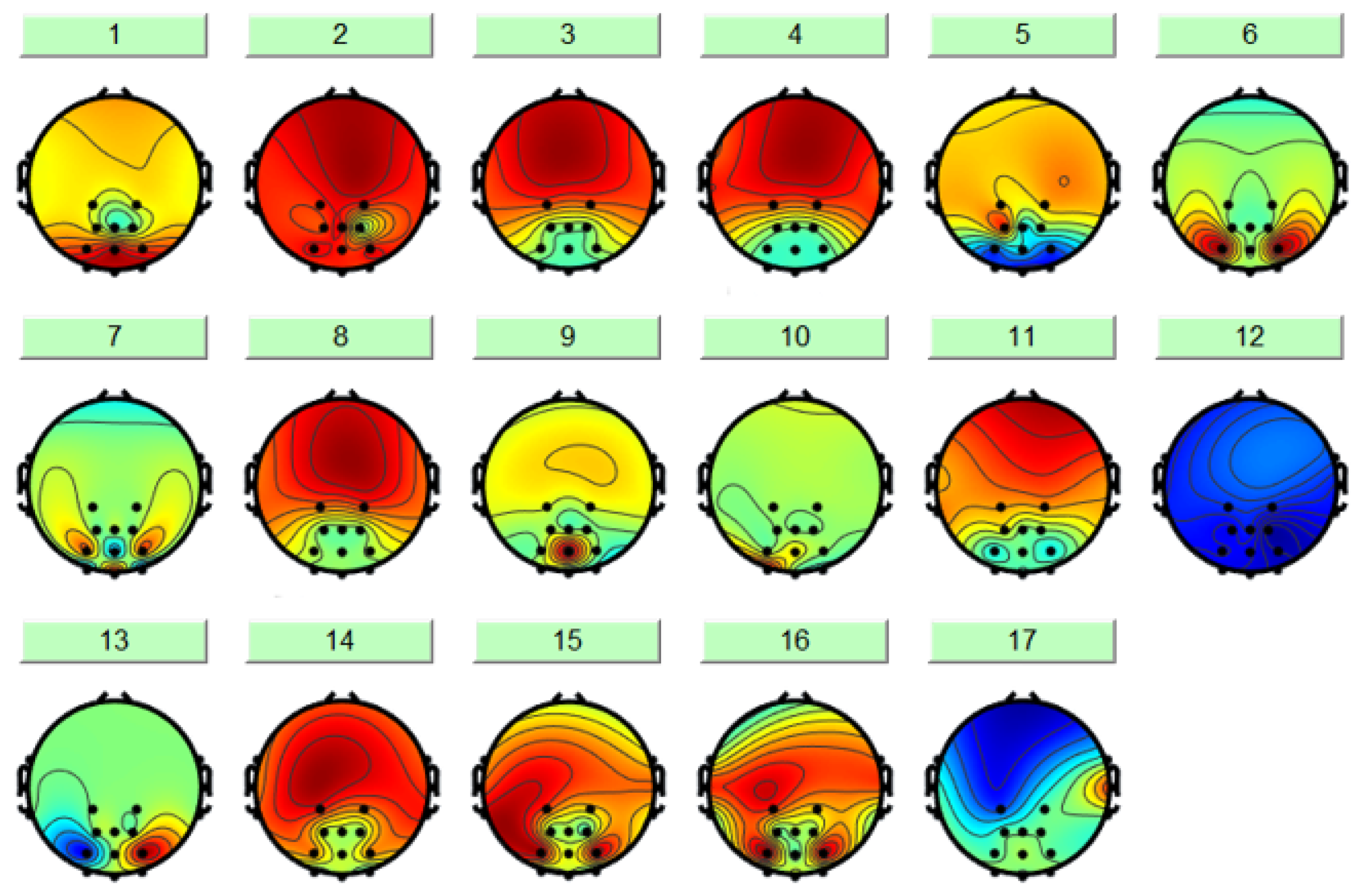

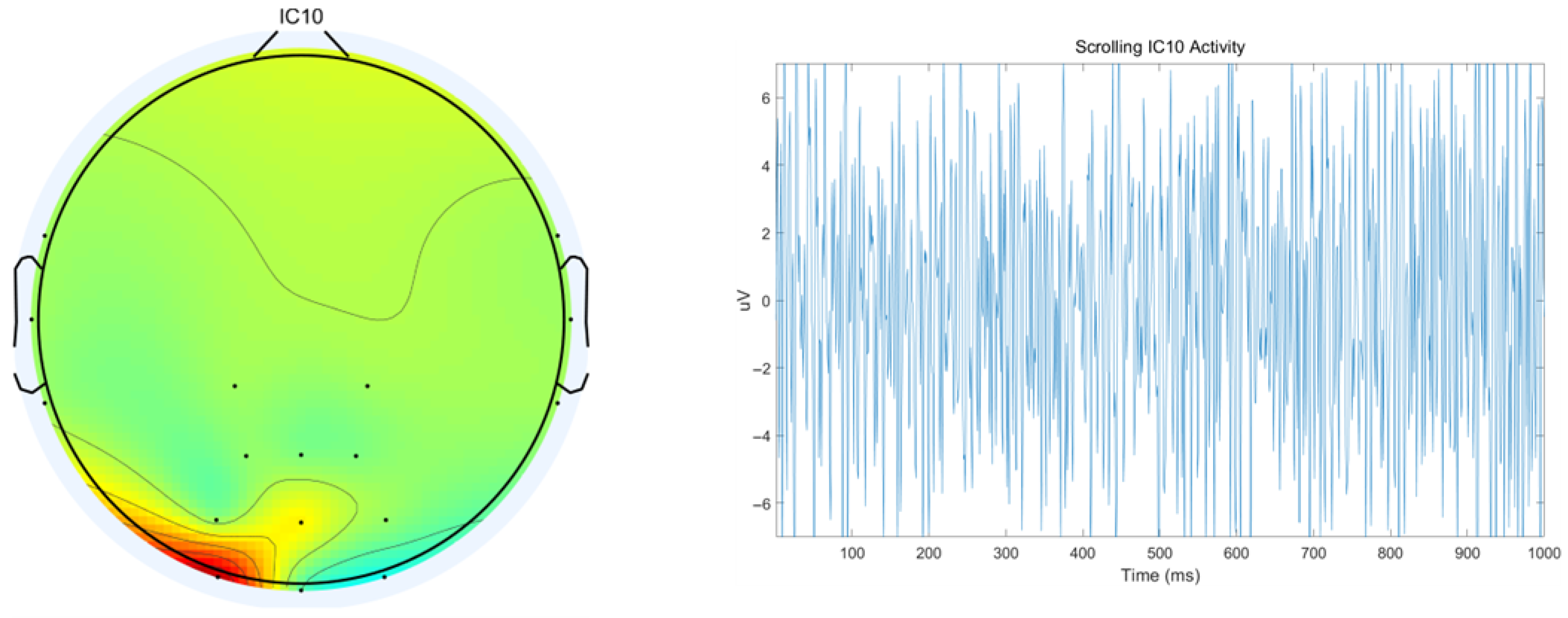

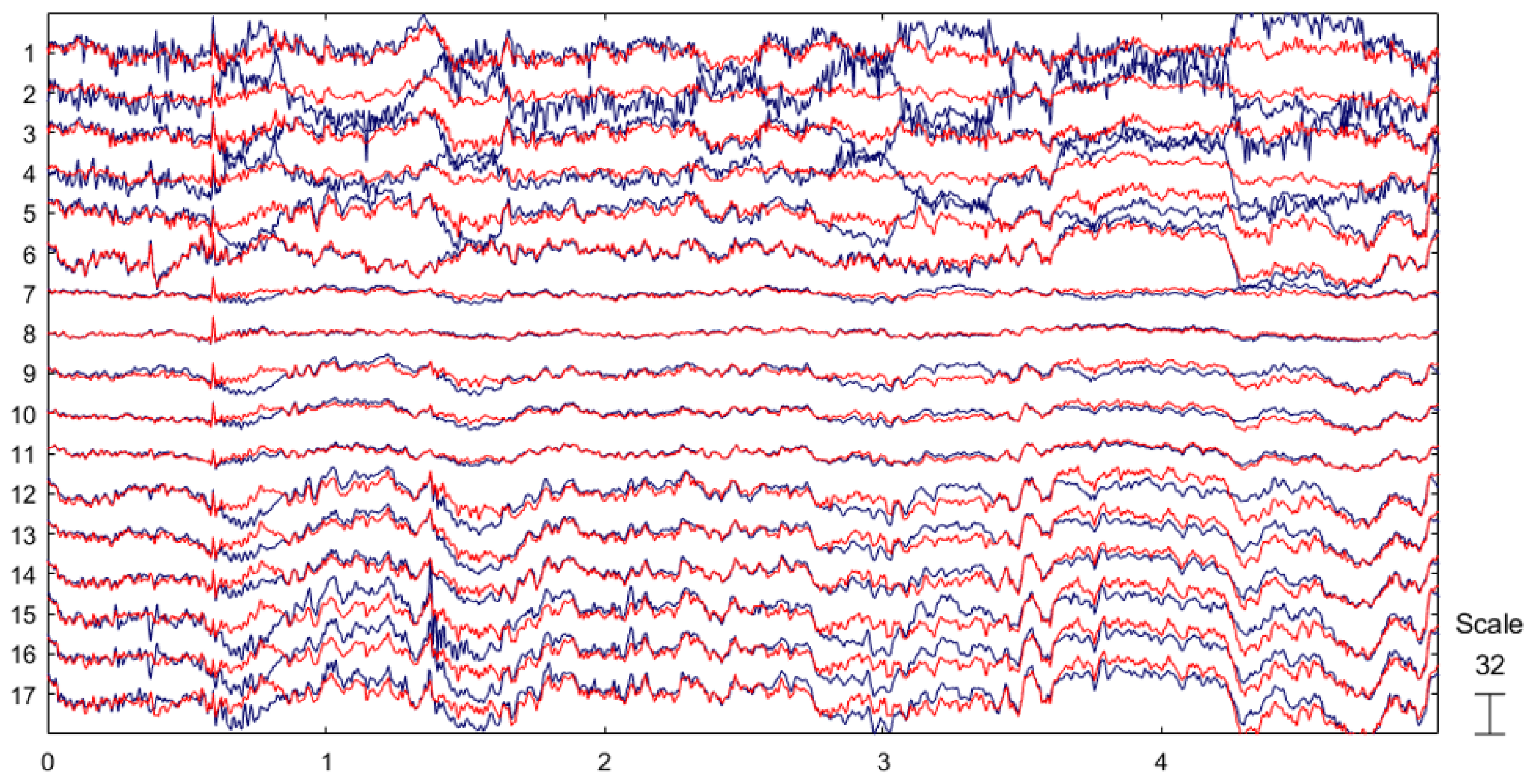

4.1. SEED-VIG Dataset

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Implementation Details

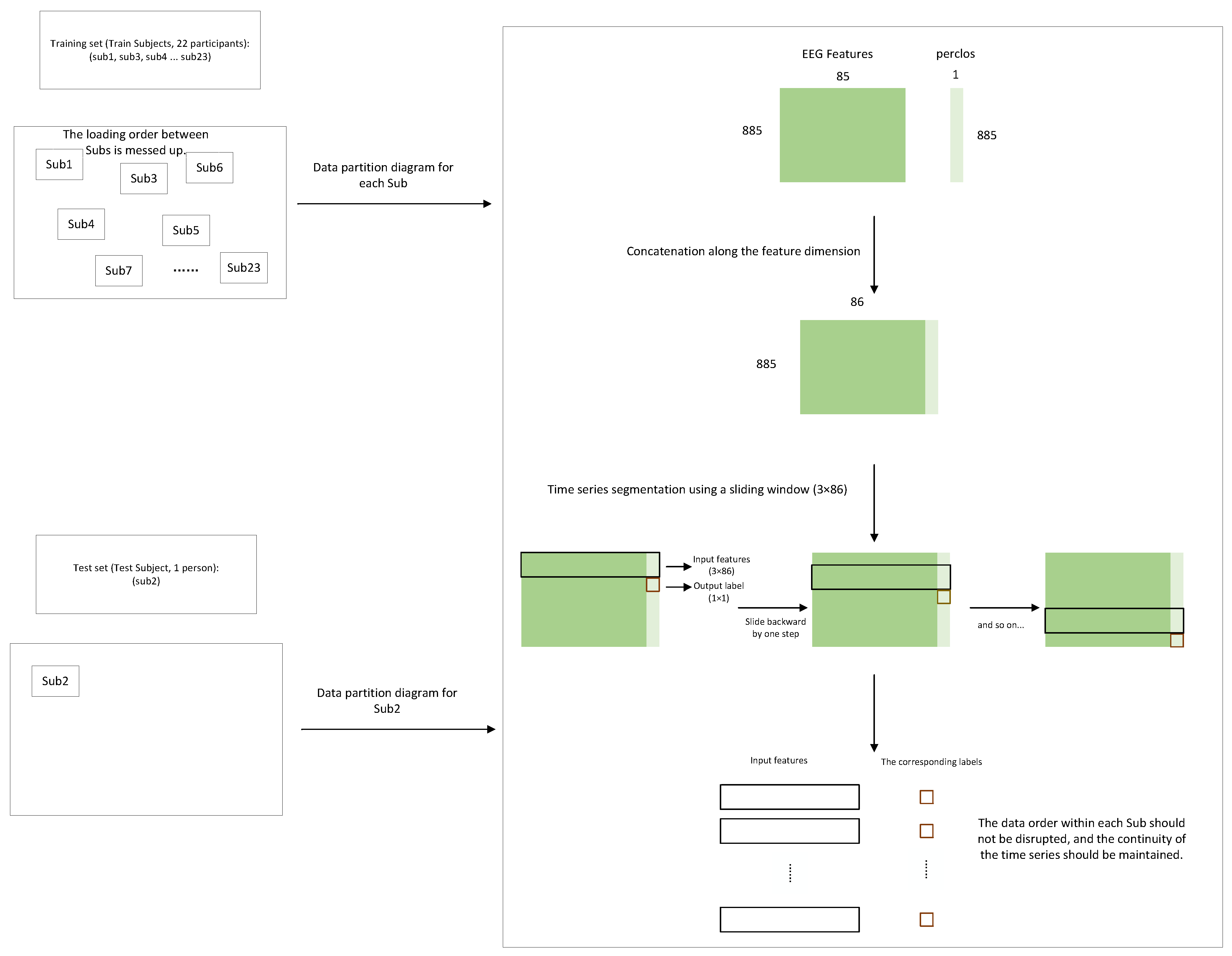

4.3.1. LOOCV Experiment

4.3.2. Cross-Subject Pre-Training with Within-Subject Fine-Tuning Experiment

4.3.3. Additional Feature Extraction

4.4. Training Settings

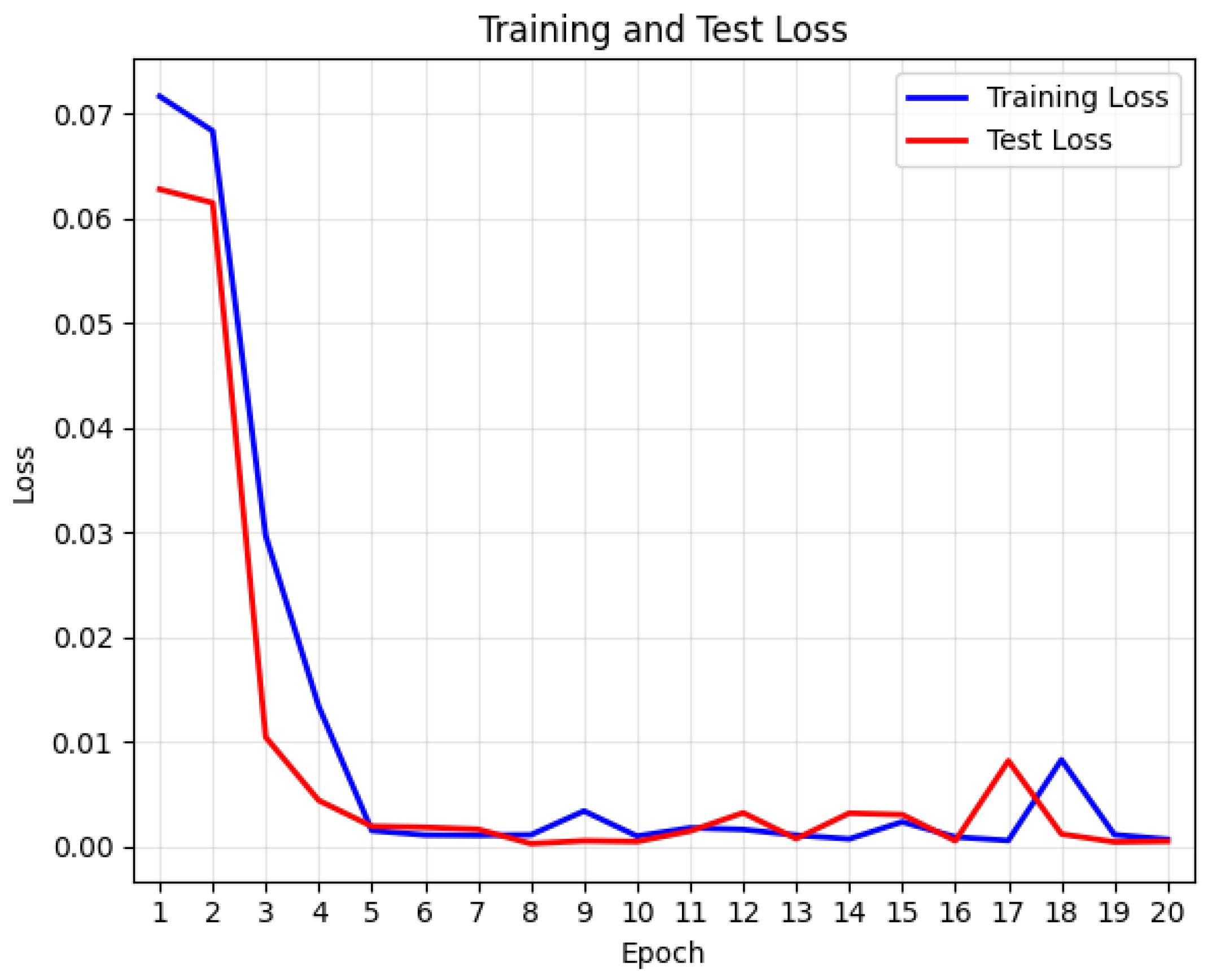

4.4.1. LOOCV Experiment

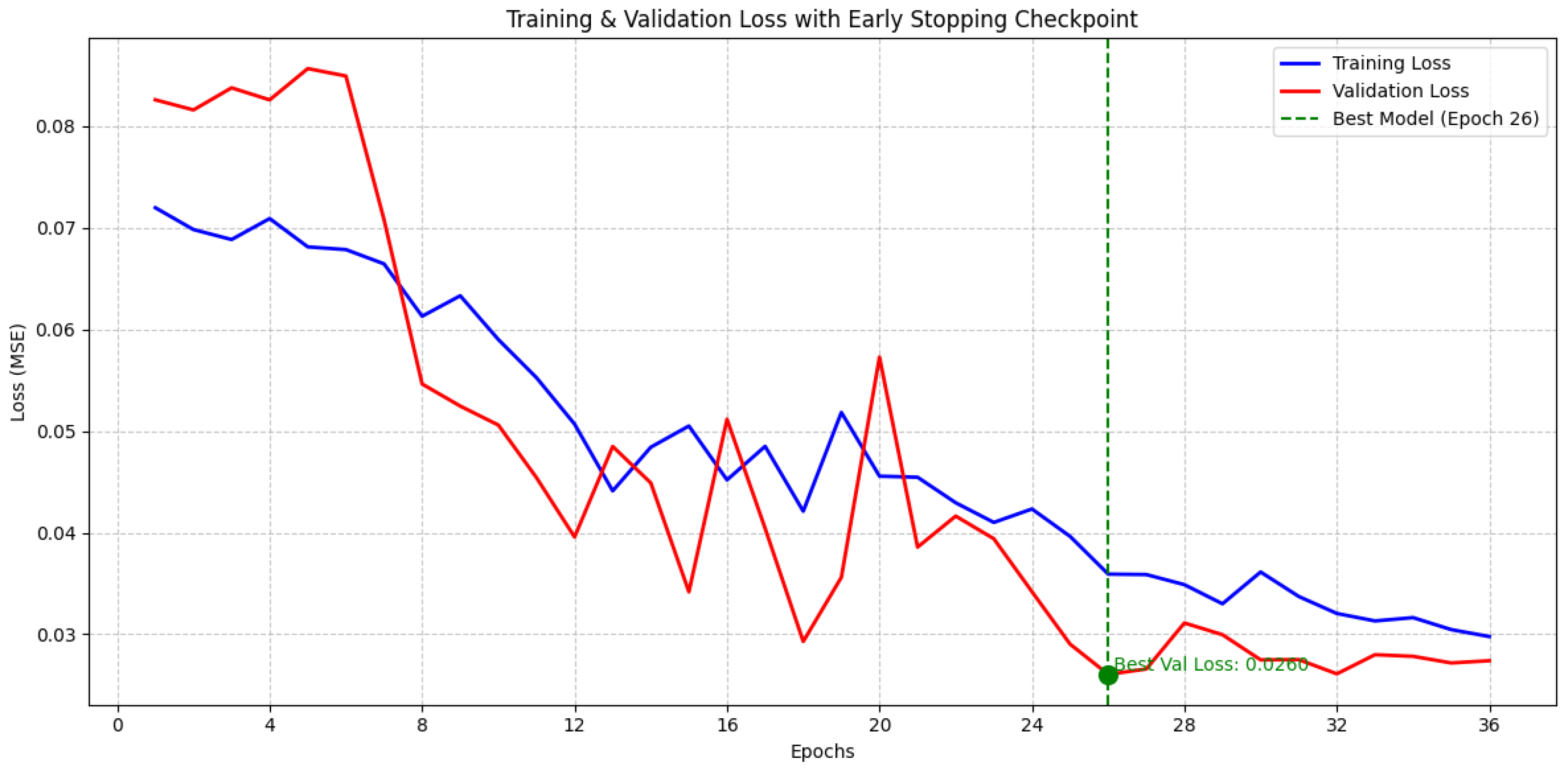

4.4.2. Cross-Subject Pre-Training with Within-Subject Fine-Tuning Experiment

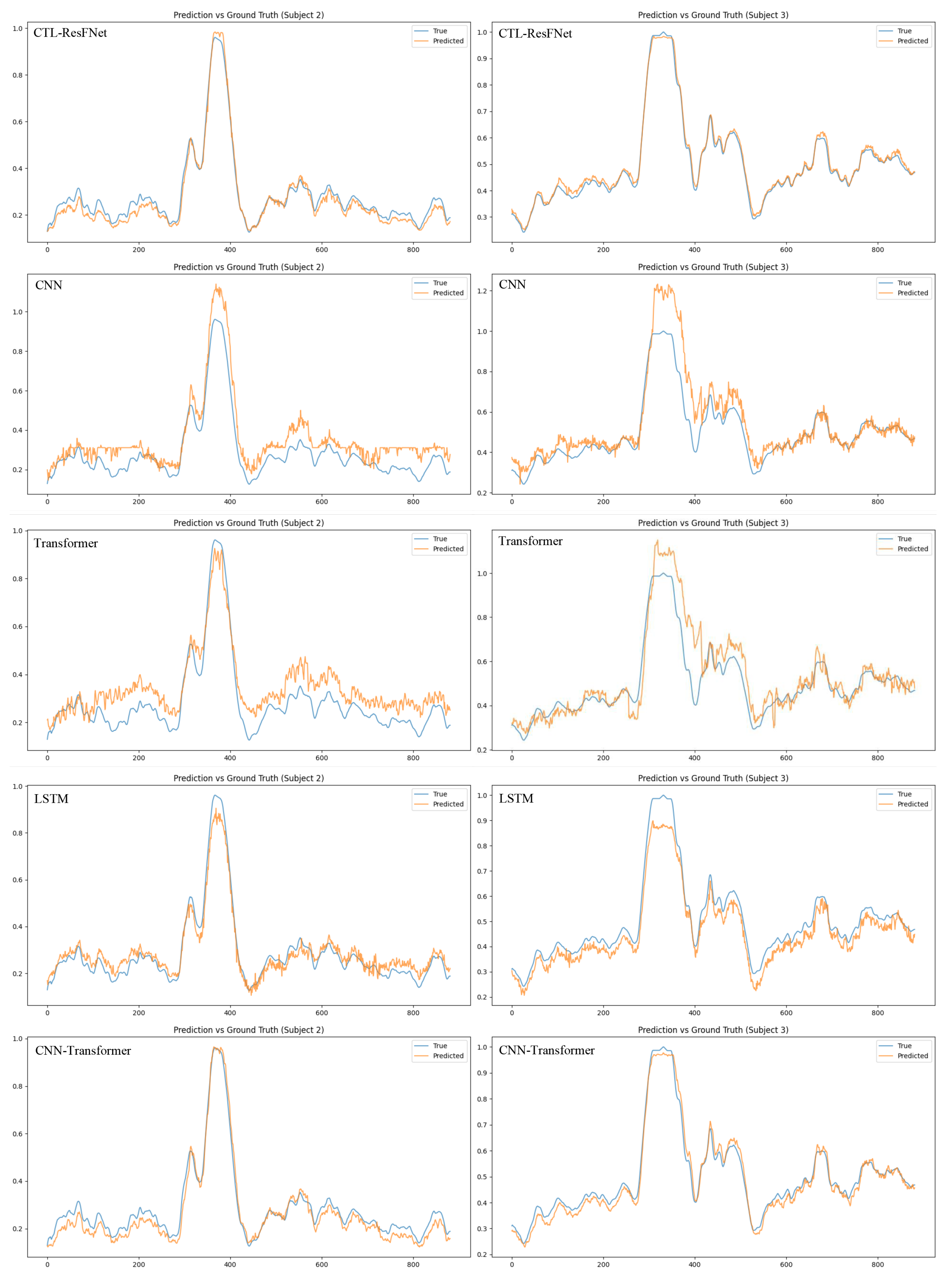

4.5. Main Results

4.5.1. Window Length Experiment

4.5.2. Comparison of Univariate and Multimodal Fatigue Prediction Based on LSTM

4.5.3. Ablation Study

- -CNN: Removing the Convolutional Neural Network module to test the importance of local feature extraction.

- -Transformer: Removing the Transformer module to evaluate the impact of the self-attention mechanism.

- -LSTM: Removing the Long Short-Term Memory network to assess the necessity of temporal dynamic modeling.

- -Residual: Removing the residual connections to verify their role in feature fusion and training stability.

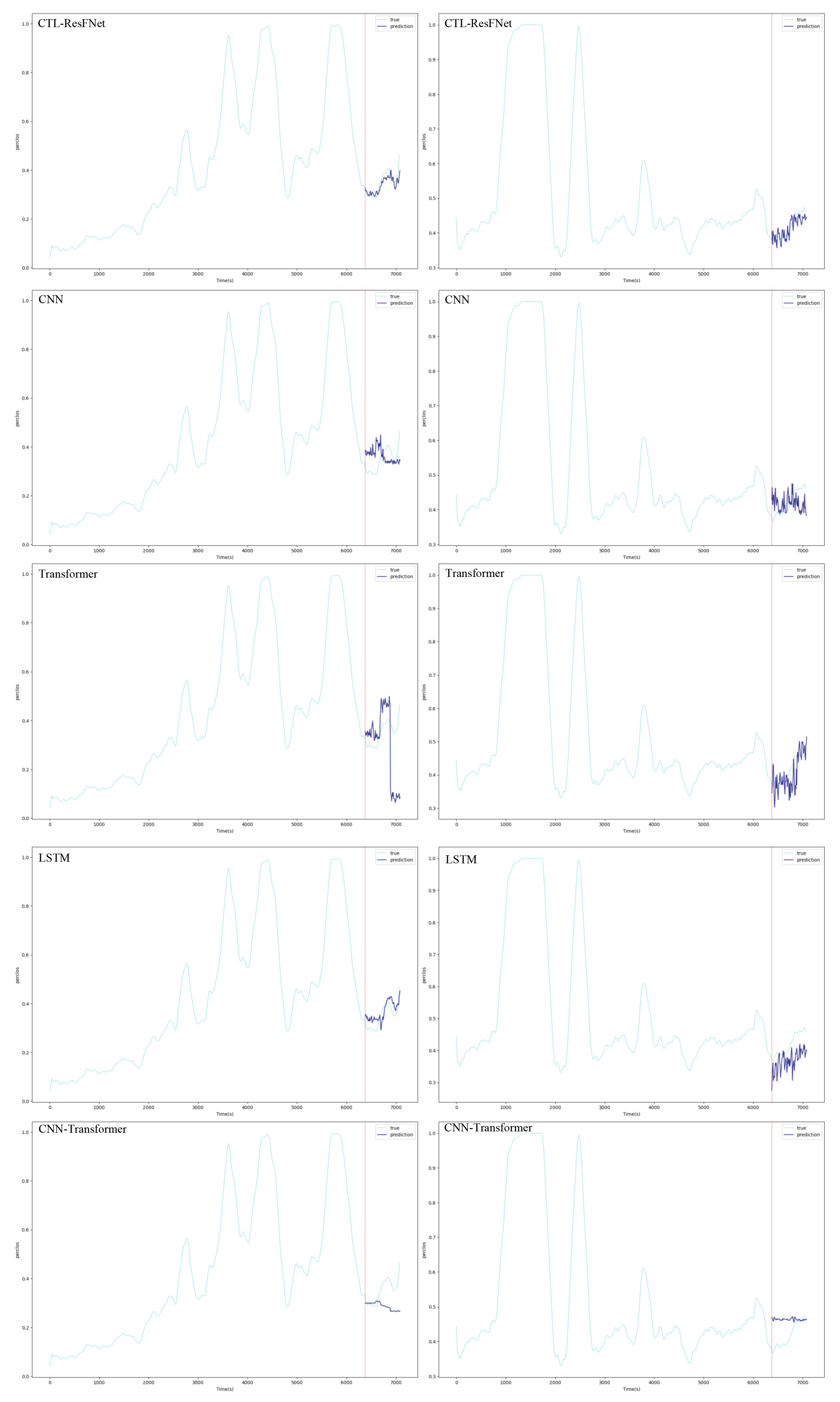

4.5.4. Cross-Subject Generalization and Individual Adaptation Analysis

4.5.5. Comparison of Feature Performance Between LOOCV and Fine-Tuning Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

| Hyperparameter | LOOCV Default Value | Pretraining–Finetuning Default Value |

|---|---|---|

| Data Processing Related | ||

| Sequence length | 3 | 3 |

| Validation set ratio | — | 0.1 |

| Test set ratio | — | 0.1 |

| Batch size | 64 | 64 |

| Normalization method | Z-Score normalization | Z-Score normalization |

| Model Architecture Related | ||

| Batch size | 64 | 64 |

| Embedding dimension | 64 | 64 |

| LSTM hidden size | 32 | 32 |

| Number of LSTM layers | 2 | 2 |

| Number of Transformer heads | 4 | 4 |

| Transformer feedforward dimension | 64 | 64 |

| Transformer dropout rate | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Convolution kernel size | 1 | 1 |

| Input feature dimension | 86 | 86 |

| Maximum positional encoding length | 1000 | 1000 |

| Positional encoding dropout rate | 0 | 0 |

| Training Strategy Related | ||

| Optimizer type | Adam | Adam |

| Loss function | MSELoss | MSELoss |

| Learning rate | 0.001 | Pretraining: 0.001/Finetuning: 0.0001 |

| Number of epochs | 20 | Pretraining: 150/Finetuning: 50 |

| Learning rate scheduler | None | ReduceLROnPlateau |

| Scheduler decay factor | — | 0.5 |

| Scheduler patience | — | 5 |

| Early stopping | None | Enabled |

| Early stopping patience | — | 10 |

| Minimum improvement threshold | — | 0.001 |

| Randomness and Device Settings | ||

| Random seed | 42 | 42 |

| Device | RTX3050 | RTX3050 |

| Environment Configuration | ||

| Python version | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| CUDA version | 11.3 | 11.3 |

| PyTorch version | 1.11.0 | 1.11.0 |

| Algorithm A1 Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) Workflow for CTL-ResFNet |

|

| Algorithm A2 Cross-Subject Pre-training with Within-Subject Fine-tuning |

|

References

- Sprajcer, M.; Dawson, D.; Kosmadopoulos, A.; Sach, E.J.; E Crowther, M.; Sargent, C.; Roach, G.D. How tired is too tired to drive? A systematic review assessing the use of prior sleep duration to detect driving impairment. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2023, 15, 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunpisuth, O.; Chotchinasri, T.; Koschakosai, V.; Hnoohom, N. Driver drowsiness detection using eye-closeness detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 12th International Conference on Signal-Image Technology & Internet-Based Systems (SITIS), Naples, Italy, 28 November–1 December 2016; pp. 661–668. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Smith, A.P. A preliminary review of fatigue among rail staff. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Masood, S.; Ahmad, M.; El-Latif, A.A.A. Intelligent driver drowsiness detection for traffic safety based on multi CNN deep model and facial subsampling. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 19743–19752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogarajan, G.; Singh, R.N.; Nandhu, S.A.; Rudhran, R.M. Drowsiness detection system using deep learning based data fusion approach. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 36081–36095. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Yu, R.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J. Semantically-Enhanced Feature Extraction with CLIP and Transformer Networks for Driver Fatigue Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, B.; Dey, D.; Munshi, S. An Attention Deep Learning Framework-Based Drowsiness Detection Model for Intelligent Transportation System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 4517–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Akbar, M.A.; Manimurugan, S.; Jiang, H. Driver Fatigue Warning Based on Medical Physiological Signal Monitoring for Transportation Cyber-Physical Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 14237–14249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Mao, X.; Song, Y.; Chen, Q. EEG-based fatigue state evaluation by combining complex network and frequency-spatial features. J. Neurosci. Methods 2025, 416, 110385. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerstedt, T.; Torsvall, L. Continuous Electrophysiological Recording. In Breakdown in Human Adaptation to ‘Stress’ Towards a Multidisciplinary Approach Volume I; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 567–583. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerstedt, T.; Kecklund, G.; Knutsson, A. Manifest sleepiness and the spectral content of the EEG during shift work. Sleep 1991, 14, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eoh, H.J.; Chung, M.K.; Kim, S.-H. Electroencephalographic study of drowsiness in simulated driving with sleep deprivation. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2005, 35, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jap, B.T.; Lal, S.; Fischer, P.; Bekiaris, E. Using EEG spectral components to assess algorithms for detecting fatigue. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 2352–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushaba, R.N.; Kodagoda, S.; Lal, S.; Dissanayake, G. Driver drowsiness classification using fuzzy wavelet-packet-based feature-extraction algorithm. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 58, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, M.; Tu, Y.; Liu, J. Multivariate autoregressive models and kernel learning algorithms for classifying driving mental fatigue based on electroencephalographic. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.-Q.; Zheng, W.-L.; Lu, B.-L. Driving fatigue detection with fusion of EEG and forehead EOG. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2016; pp. 897–904. [Google Scholar]

- Chaabene, S.; Bouaziz, B.; Boudaya, A.; Hökelmann, A.; Ammar, A.; Chaari, L. Convolutional neural network for drowsiness detection using EEG signals. Sensors 2021, 21, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Lan, Z.; Sourina, O.; Müller-Wittig, W. EEG-based cross-subject driver drowsiness recognition with an interpretable convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 34, 7921–7933. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.-C.; Jiao, Y.-Y.; Lu, B.-L. Differential entropy feature for EEG-based vigilance estimation. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Osaka, Japan, 3–7 July 2013; pp. 6627–6630. [Google Scholar]

- Bashivan, P.; Rish, I.; Yeasin, M.; Codella, N. Learning representations from EEG with deep recurrent-convolutional neural networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.06448. [Google Scholar]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 2002, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Deng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Lu, B.-L. Driver sleepiness detection from EEG and EOG signals using GAN and LSTM networks. Neurocomputing 2020, 408, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitan, L.; Teicher, M.; Abeles, M. EEG generator—A model of potentials in a volume conductor. J. Neurophysiol. 2009, 102, 3046–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharagozlou, F.; Saraji, G.N.; Mazloumi, A.; Nahvi, A.; Nasrabadi, A.M.; Foroushani, A.R.; Kheradmand, A.A.; Ashouri, M.; Samavati, M. Detecting driver mental fatigue based on EEG alpha power changes during simulated driving. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 1693. [Google Scholar]

- Panicker, R.C.; Puthusserypady, S.; Sun, Y. An asynchronous P300 BCI with SSVEP-based control state detection. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 58, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wu, D. EEG-based driver drowsiness estimation using feature weighted episodic training. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2019, 27, 2263–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Mu, C.; Cai, Q.; Dang, W.; Zuo, S. EEG-based spatio–temporal convolutional neural network for driver fatigue evaluation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, M.; Kurt, M.B.; Sezgin, N.; Bayram, M. Estimating vigilance level by using EEG and EMG signals. Neural Comput. Appl. 2008, 17, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.-L.; Lu, B.-L. A multimodal approach to estimating vigilance using EEG and forehead EOG. J. Neural Eng. 2017, 14, 026017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, Z. EEG Signal Processing and Feature Extraction; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luck, S.J. An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.-S.; Lin, Y.-P.; Wang, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-T.; Jung, T.-P. A subject-transfer framework for obviating inter-and intra-subject variability in EEG-based drowsiness detection. NeuroImage 2018, 174, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.-S.; Wang, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-T.; Jung, T.-P. Toward drowsiness detection using non-hair-bearing EEG-based brain-computer interfaces. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lan, Z.; Cui, J.; Sourina, O.; Müller-Wittig, W. Inter-subject transfer learning for EEG-based mental fatigue recognition. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 46, 101157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Fu, R. Automated detection of driver fatigue based on entropy and complexity measures. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2013, 15, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigari, M.-H.; Fathy, M.; Soryani, M. A driver face monitoring system for fatigue and distraction detection. Int. J. Veh. Technol. 2013, 2013, 263983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. A new real-time eye tracking based on nonlinear unscented Kalman filter for monitoring driver fatigue. J. Control Theory Appl. 2010, 8, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Zhang, L.; Su, K.; Wang, X.; Teng, S.; Liu, P.X. A multimodal fusion fatigue driving detection method based on heart rate and PERCLOS. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 21810–21820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M. Detection of operator fatigue in the main control room of a nuclear power plant based on eye blink rate, PERCLOS and mouse velocity. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, S.; Nanda, A.; Swarnkar, T. A survey on transfer learning. In Intelligent and Cloud Computing: Proceedings of ICICC 2019, Volume 1; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 781–789. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Ruder, S.; Peters, M.E.; Swayamdipta, S.; Wolf, T. Transfer learning in natural language processing. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Tutorials, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Maqsood, M.; Nazir, F.; Khan, U.; Aadil, F.; Jamal, H.; Mehmood, I.; Song, O.-Y. Transfer learning assisted classification and detection of Alzheimer’s disease stages using 3D MRI scans. Sensors 2019, 19, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweikert, G.; Rätsch, G.; Widmer, C.; Schölkopf, B. An empirical analysis of domain adaptation algorithms for genomic sequence analysis. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–11 December 2008; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Hyvärinen, A.; Oja, E. Independent component analysis: Algorithms and applications. Neural Netw. 2000, 13, 411–430. [Google Scholar]

- Särkelä, M.O.K.; Ermes, M.J.; van Gils, M.J.; Yli-Hankala, A.M.; Jäntti, V.H.; Vakkuri, A.P. Quantification of epileptiform electroencephalographic activity during sevoflurane mask induction. Anesthesiology 2007, 107, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H. Long-term storage of reservoirs: An experimental study. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1951, 116, 770–799. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

| Component | Parameters |

|---|---|

| PositionalEncoding | d_model = 86 |

| Conv1d | input = 86, output = 64, kernel = 1 |

| TransformerEncoderLayer | d_model = 64, nhead = 4, dim_feedforward = 64 |

| TransformerEncoder | 1 layer |

| LSTM | input = 64, hidden = 32, layers = 2 |

| FC | input = 32, output = 1 |

| Sub. | Window Length 1 | Window Length 2 | Window Length 3 | Window Length 4 | Window Length 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| 1 | 0.1154 | 0.1004 | 0.1131 | 0.0974 | 0.0768 | 0.0652 | 0.0793 | 0.0711 | 0.0733 | 0.0630 |

| 2 | 0.0493 | 0.0393 | 0.0481 | 0.0414 | 0.0356 | 0.0302 | 0.0830 | 0.0723 | 0.0283 | 0.0213 |

| 3 | 0.0861 | 0.0767 | 0.0778 | 0.0728 | 0.0469 | 0.0407 | 0.0523 | 0.0489 | 0.0935 | 0.0870 |

| 4 | 0.0531 | 0.0433 | 0.1000 | 0.0844 | 0.0443 | 0.0371 | 0.0508 | 0.0417 | 0.0754 | 0.0664 |

| 5 | 0.0572 | 0.0468 | 0.0636 | 0.0564 | 0.0730 | 0.0651 | 0.0710 | 0.0619 | 0.0817 | 0.0724 |

| 6 | 0.0888 | 0.0659 | 0.0615 | 0.0488 | 0.0582 | 0.0429 | 0.0625 | 0.0467 | 0.0741 | 0.0611 |

| 7 | 0.1650 | 0.1161 | 0.1764 | 0.1170 | 0.0526 | 0.0445 | 0.1352 | 0.1010 | 0.0910 | 0.0698 |

| 8 | 0.0580 | 0.0479 | 0.0305 | 0.0249 | 0.0672 | 0.0622 | 0.0463 | 0.0436 | 0.0524 | 0.0492 |

| 9 | 0.1202 | 0.1091 | 0.1809 | 0.1655 | 0.0566 | 0.0538 | 0.0378 | 0.0327 | 0.0549 | 0.0518 |

| 10 | 0.0343 | 0.0276 | 0.0413 | 0.0319 | 0.0545 | 0.0411 | 0.0351 | 0.0269 | 0.0377 | 0.0295 |

| 11 | 0.0235 | 0.0183 | 0.0418 | 0.0323 | 0.0365 | 0.0281 | 0.0474 | 0.0439 | 0.0498 | 0.0467 |

| 12 | 0.0486 | 0.0440 | 0.0438 | 0.0393 | 0.0451 | 0.0394 | 0.0474 | 0.0435 | 0.0482 | 0.0448 |

| 13 | 0.0321 | 0.0283 | 0.0384 | 0.0307 | 0.0707 | 0.0649 | 0.0622 | 0.0578 | 0.0822 | 0.0750 |

| 14 | 0.0828 | 0.0675 | 0.0843 | 0.0689 | 0.0692 | 0.0566 | 0.0635 | 0.0512 | 0.0637 | 0.0520 |

| 15 | 0.1075 | 0.0990 | 0.0575 | 0.0511 | 0.0706 | 0.0607 | 0.0499 | 0.0425 | 0.0684 | 0.0604 |

| 16 | 0.0677 | 0.0567 | 0.0719 | 0.0600 | 0.0497 | 0.0433 | 0.0464 | 0.0372 | 0.0591 | 0.0510 |

| 17 | 0.0555 | 0.0502 | 0.0442 | 0.0377 | 0.0483 | 0.0438 | 0.0547 | 0.0493 | 0.0466 | 0.0416 |

| 18 | 0.0600 | 0.0490 | 0.1009 | 0.0876 | 0.0789 | 0.0704 | 0.0687 | 0.0602 | 0.0698 | 0.0621 |

| 19 | 0.0573 | 0.0446 | 0.0573 | 0.0495 | 0.0709 | 0.0596 | 0.0627 | 0.0501 | 0.0668 | 0.0559 |

| 20 | 0.0918 | 0.0719 | 0.0927 | 0.0713 | 0.0827 | 0.0688 | 0.0619 | 0.0531 | 0.0569 | 0.0482 |

| 21 | 0.0365 | 0.0336 | 0.0436 | 0.0339 | 0.0581 | 0.0522 | 0.1008 | 0.0791 | 0.0389 | 0.0363 |

| 22 | 0.0759 | 0.0628 | 0.0719 | 0.0491 | 0.0528 | 0.0425 | 0.0553 | 0.0414 | 0.0746 | 0.0573 |

| 23 | 0.0821 | 0.0711 | 0.0605 | 0.0506 | 0.0764 | 0.0574 | 0.0495 | 0.0412 | 0.0559 | 0.0435 |

| Avg. | 0.0717 | 0.0596 | 0.0740 | 0.0609 | 0.0598 | 0.0509 | 0.0619 | 0.0521 | 0.0627 | 0.0542 |

| Sub. | EEG + PERCLOS | PERCLOS-Only | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| 1 | 0.0768 | 0.0652 | 0.0842 | 0.0767 |

| 2 | 0.0356 | 0.0302 | 0.0399 | 0.0335 |

| 3 | 0.0469 | 0.0407 | 0.0595 | 0.0557 |

| 4 | 0.0443 | 0.0371 | 0.0465 | 0.0390 |

| 5 | 0.0730 | 0.0651 | 0.0672 | 0.0575 |

| 6 | 0.0582 | 0.0429 | 0.0852 | 0.0644 |

| 7 | 0.0526 | 0.0445 | 0.0564 | 0.0462 |

| 8 | 0.0672 | 0.0622 | 0.0491 | 0.0458 |

| 9 | 0.0566 | 0.0538 | 0.0520 | 0.0496 |

| 10 | 0.0545 | 0.0411 | 0.0592 | 0.0437 |

| 11 | 0.0365 | 0.0281 | 0.0537 | 0.0502 |

| 12 | 0.0451 | 0.0394 | 0.0542 | 0.0496 |

| 13 | 0.0707 | 0.0649 | 0.0698 | 0.0656 |

| 14 | 0.0692 | 0.0566 | 0.0866 | 0.0703 |

| 15 | 0.0706 | 0.0607 | 0.0861 | 0.0813 |

| 16 | 0.0497 | 0.0433 | 0.0640 | 0.0541 |

| 17 | 0.0483 | 0.0438 | 0.0464 | 0.0416 |

| 18 | 0.0789 | 0.0704 | 0.0802 | 0.0700 |

| 19 | 0.0709 | 0.0596 | 0.0853 | 0.0776 |

| 20 | 0.0827 | 0.0688 | 0.1028 | 0.0843 |

| 21 | 0.0581 | 0.0522 | 0.0706 | 0.0677 |

| 22 | 0.0528 | 0.0425 | 0.0786 | 0.0492 |

| 23 | 0.0764 | 0.0574 | 0.0941 | 0.0581 |

| Avg. | 0.0598 | 0.0509 | 0.0683 | 0.0579 |

| Sub. | CTL-ResFNet | -CNN | -Transformer | -LSTM | -Residual | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| 1 | 0.0411 | 0.0362 | 0.0421 | 0.0344 | 0.0369 | 0.0322 | 0.0779 | 0.0604 | 0.0251 | 0.0207 |

| 2 | 0.0257 | 0.0222 | 0.0403 | 0.0358 | 0.0539 | 0.0482 | 0.0350 | 0.0302 | 0.0807 | 0.0694 |

| 3 | 0.0136 | 0.0110 | 0.0252 | 0.0226 | 0.0551 | 0.0489 | 0.0825 | 0.0751 | 0.0612 | 0.0426 |

| 4 | 0.0401 | 0.0302 | 0.0314 | 0.0254 | 0.0288 | 0.0236 | 0.0335 | 0.0254 | 0.0446 | 0.0337 |

| 5 | 0.0256 | 0.0209 | 0.0381 | 0.0314 | 0.0193 | 0.0155 | 0.0360 | 0.0304 | 0.1461 | 0.1168 |

| 6 | 0.0332 | 0.0255 | 0.0350 | 0.0280 | 0.0315 | 0.0226 | 0.0374 | 0.0280 | 0.0743 | 0.0555 |

| 7 | 0.0261 | 0.0153 | 0.0487 | 0.0383 | 0.1290 | 0.0934 | 0.0347 | 0.0275 | 0.0681 | 0.0537 |

| 8 | 0.0231 | 0.0204 | 0.0590 | 0.0523 | 0.0470 | 0.0400 | 0.0315 | 0.0240 | 0.0731 | 0.0562 |

| 9 | 0.0215 | 0.0177 | 0.0589 | 0.0517 | 0.0541 | 0.0482 | 0.0812 | 0.0733 | 0.0776 | 0.0675 |

| 10 | 0.0194 | 0.0165 | 0.0401 | 0.0333 | 0.0356 | 0.0269 | 0.0332 | 0.0252 | 0.1121 | 0.0959 |

| 11 | 0.0415 | 0.0380 | 0.0496 | 0.0437 | 0.0171 | 0.0148 | 0.0478 | 0.0397 | 0.0482 | 0.0389 |

| 12 | 0.0158 | 0.0128 | 0.1085 | 0.0925 | 0.0216 | 0.0180 | 0.1245 | 0.1022 | 0.0446 | 0.0341 |

| 13 | 0.0160 | 0.0128 | 0.0296 | 0.0249 | 0.0137 | 0.0107 | 0.0398 | 0.0347 | 0.0772 | 0.0657 |

| 14 | 0.0283 | 0.0263 | 0.0584 | 0.0493 | 0.0216 | 0.0191 | 0.0798 | 0.0734 | 0.0966 | 0.0738 |

| 15 | 0.0224 | 0.0180 | 0.0288 | 0.0227 | 0.0188 | 0.0155 | 0.0663 | 0.0484 | 0.0801 | 0.0537 |

| 16 | 0.0355 | 0.0239 | 0.0309 | 0.0221 | 0.0191 | 0.0152 | 0.0411 | 0.0307 | 0.0678 | 0.0470 |

| 17 | 0.0224 | 0.0171 | 0.0194 | 0.0171 | 0.0186 | 0.0153 | 0.0206 | 0.0141 | 0.0395 | 0.0311 |

| 18 | 0.0204 | 0.0171 | 0.0243 | 0.0188 | 0.0249 | 0.0184 | 0.0706 | 0.0603 | 0.0435 | 0.0357 |

| 19 | 0.0191 | 0.0154 | 0.0170 | 0.0137 | 0.0169 | 0.0146 | 0.0444 | 0.0257 | 0.0512 | 0.0360 |

| 20 | 0.0426 | 0.0311 | 0.1139 | 0.0662 | 0.0190 | 0.0160 | 0.0593 | 0.0485 | 0.1170 | 0.0902 |

| 21 | 0.0113 | 0.0082 | 0.0285 | 0.0172 | 0.0167 | 0.0139 | 0.0163 | 0.0131 | 0.0331 | 0.0290 |

| 22 | 0.0139 | 0.0115 | 0.0238 | 0.0172 | 0.0241 | 0.0194 | 0.0554 | 0.0512 | 0.0268 | 0.0215 |

| 23 | 0.0549 | 0.0471 | 0.0807 | 0.0735 | 0.0371 | 0.0320 | 0.0721 | 0.0627 | 0.1041 | 0.0935 |

| Avg. | 0.0266 | 0.0215 | 0.0449 | 0.0362 | 0.0331 | 0.0271 | 0.0531 | 0.0437 | 0.0692 | 0.0549 |

| Sub. | CTL-ResFNet | CNN | Transformer | LSTM | CNN-Transformer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| 1 | 0.0411 | 0.0362 | 0.0405 | 0.0315 | 0.0589 | 0.0489 | 0.0768 | 0.0652 | 0.0453 | 0.0400 |

| 2 | 0.0257 | 0.0222 | 0.0830 | 0.0715 | 0.0789 | 0.0706 | 0.0356 | 0.0302 | 0.0331 | 0.0289 |

| 3 | 0.0136 | 0.0110 | 0.0873 | 0.0543 | 0.0793 | 0.0519 | 0.0469 | 0.0407 | 0.0239 | 0.0203 |

| 4 | 0.0401 | 0.0302 | 0.1599 | 0.0786 | 0.0792 | 0.0566 | 0.0443 | 0.0371 | 0.0267 | 0.0209 |

| 5 | 0.0256 | 0.0209 | 0.0770 | 0.0649 | 0.1258 | 0.1045 | 0.0730 | 0.0651 | 0.0420 | 0.0338 |

| 6 | 0.0332 | 0.0255 | 0.1426 | 0.1195 | 0.0752 | 0.0573 | 0.0582 | 0.0429 | 0.0337 | 0.0272 |

| 7 | 0.0261 | 0.0153 | 0.4533 | 0.3604 | 0.1719 | 0.1279 | 0.0526 | 0.0445 | 0.0460 | 0.0390 |

| 8 | 0.0231 | 0.0204 | 0.0444 | 0.0331 | 0.0570 | 0.0466 | 0.0672 | 0.0622 | 0.0337 | 0.0275 |

| 9 | 0.0215 | 0.0177 | 0.0260 | 0.0186 | 0.0613 | 0.0478 | 0.0566 | 0.0538 | 0.0559 | 0.0494 |

| 10 | 0.0194 | 0.0165 | 0.0594 | 0.0515 | 0.0846 | 0.0640 | 0.0545 | 0.0411 | 0.0311 | 0.0232 |

| 11 | 0.0415 | 0.0380 | 0.0658 | 0.0571 | 0.0663 | 0.0505 | 0.0365 | 0.0281 | 0.0334 | 0.0293 |

| 12 | 0.0158 | 0.0128 | 0.0609 | 0.0457 | 0.1105 | 0.0763 | 0.0451 | 0.0394 | 0.0327 | 0.0274 |

| 13 | 0.0160 | 0.0128 | 0.0933 | 0.0269 | 0.0974 | 0.0815 | 0.0707 | 0.0649 | 0.0402 | 0.0340 |

| 14 | 0.0283 | 0.0263 | 0.1164 | 0.0905 | 0.1113 | 0.0930 | 0.0692 | 0.0566 | 0.0414 | 0.0341 |

| 15 | 0.0224 | 0.0180 | 0.1121 | 0.0945 | 0.1085 | 0.0847 | 0.0706 | 0.0607 | 0.0421 | 0.0356 |

| 16 | 0.0355 | 0.0239 | 0.1100 | 0.0804 | 0.0656 | 0.0525 | 0.0497 | 0.0433 | 0.0398 | 0.0299 |

| 17 | 0.0224 | 0.0171 | 0.0516 | 0.0399 | 0.0717 | 0.0600 | 0.0483 | 0.0438 | 0.0234 | 0.0182 |

| 18 | 0.0204 | 0.0171 | 0.1077 | 0.0889 | 0.1352 | 0.1165 | 0.0789 | 0.0704 | 0.0385 | 0.0313 |

| 19 | 0.0191 | 0.0154 | 0.0476 | 0.0390 | 0.1430 | 0.1301 | 0.0709 | 0.0596 | 0.0339 | 0.0267 |

| 20 | 0.0426 | 0.0311 | 0.2137 | 0.1666 | 0.1186 | 0.1010 | 0.0827 | 0.0688 | 0.0429 | 0.0329 |

| 21 | 0.0113 | 0.0082 | 0.1304 | 0.0702 | 0.0702 | 0.0460 | 0.0581 | 0.0522 | 0.0354 | 0.0282 |

| 22 | 0.0139 | 0.0115 | 0.1097 | 0.0904 | 0.1143 | 0.1012 | 0.0528 | 0.0425 | 0.0386 | 0.0326 |

| 23 | 0.0549 | 0.0471 | 0.1052 | 0.0910 | 0.0772 | 0.0650 | 0.0764 | 0.0574 | 0.0631 | 0.0569 |

| Avg. | 0.0266 | 0.0215 | 0.1062 | 0.0811 | 0.0940 | 0.0754 | 0.0598 | 0.0509 | 0.0381 | 0.0316 |

| Sub. | CTL-ResFNet | CNN | Transformer | LSTM | CNN-Transformer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| 1 | 0.0614 | 0.0575 | 0.2610 | 0.2535 | 0.1310 | 0.1103 | 0.2582 | 0.2568 | 0.0222 | 0.0203 |

| 2 | 0.0562 | 0.0463 | 0.0811 | 0.0707 | 0.1869 | 0.1822 | 0.0442 | 0.0357 | 0.1210 | 0.1128 |

| 3 | 0.0273 | 0.0234 | 0.0432 | 0.0362 | 0.0684 | 0.0571 | 0.0970 | 0.0925 | 0.0506 | 0.0470 |

| 4 | 0.0248 | 0.0207 | 0.0702 | 0.0618 | 0.1581 | 0.1448 | 0.0372 | 0.0300 | 0.0783 | 0.0692 |

| 5 | 0.1746 | 0.1570 | 0.1398 | 0.1190 | 0.1230 | 0.1080 | 0.2056 | 0.1797 | 0.1779 | 0.1571 |

| 6 | 0.1457 | 0.1382 | 0.3041 | 0.2758 | 0.1021 | 0.0918 | 0.3290 | 0.2918 | 0.1325 | 0.1248 |

| 7 | 0.0214 | 0.0170 | 0.0695 | 0.0604 | 0.1633 | 0.1239 | 0.0531 | 0.0318 | 0.0809 | 0.0638 |

| 8 | 0.0665 | 0.0529 | 0.0353 | 0.0284 | 0.0394 | 0.0314 | 0.0389 | 0.0325 | 0.0704 | 0.0617 |

| 9 | 0.0519 | 0.0352 | 0.0462 | 0.0381 | 0.0656 | 0.0425 | 0.0429 | 0.0354 | 0.0763 | 0.0566 |

| 10 | 0.2650 | 0.2406 | 0.2357 | 0.2272 | 0.2391 | 0.2228 | 0.2003 | 0.1892 | 0.2902 | 0.2312 |

| 11 | 0.0337 | 0.0302 | 0.0389 | 0.0308 | 0.1015 | 0.0945 | 0.0530 | 0.0466 | 0.0641 | 0.0552 |

| 12 | 0.0920 | 0.0827 | 0.0968 | 0.0739 | 0.0939 | 0.0787 | 0.0495 | 0.0426 | 0.1488 | 0.1311 |

| 13 | 0.0468 | 0.0357 | 0.0660 | 0.0552 | 0.0657 | 0.0579 | 0.1504 | 0.1451 | 0.0650 | 0.0516 |

| 14 | 0.2876 | 0.2601 | 0.4093 | 0.3695 | 0.2025 | 0.1783 | 0.2420 | 0.2182 | 0.4397 | 0.3945 |

| 15 | 0.1545 | 0.1545 | 0.1620 | 0.1494 | 0.0755 | 0.0521 | 0.1659 | 0.1632 | 0.0124 | 0.0118 |

| 16 | 0.1401 | 0.1099 | 0.1397 | 0.1182 | 0.1243 | 0.0996 | 0.1584 | 0.1210 | 0.1969 | 0.1514 |

| 17 | 0.0465 | 0.0405 | 0.0573 | 0.0454 | 0.0975 | 0.0850 | 0.0571 | 0.0458 | 0.0794 | 0.0728 |

| 18 | 0.1168 | 0.1157 | 0.3279 | 0.3212 | 0.1627 | 0.1425 | 0.3749 | 0.3714 | 0.2220 | 0.1951 |

| 19 | 0.0191 | 0.0165 | 0.0445 | 0.0369 | 0.0419 | 0.0320 | 0.0572 | 0.0505 | 0.0577 | 0.0466 |

| 20 | 0.0461 | 0.0413 | 0.1481 | 0.1364 | 0.0932 | 0.0796 | 0.0599 | 0.0475 | 0.1290 | 0.1198 |

| 21 | 0.0528 | 0.0486 | 0.0395 | 0.0340 | 0.0484 | 0.0414 | 0.0808 | 0.0783 | 0.0577 | 0.0504 |

| 22 | 0.0624 | 0.0589 | 0.0940 | 0.0855 | 0.0629 | 0.0494 | 0.0398 | 0.0308 | 0.0493 | 0.0451 |

| 23 | 0.1574 | 0.1519 | 0.3042 | 0.2809 | 0.1172 | 0.0971 | 0.2366 | 0.2201 | 0.1871 | 0.1056 |

| Avg. | 0.0935 | 0.0841 | 0.1398 | 0.1265 | 0.1115 | 0.0958 | 0.1310 | 0.1198 | 0.1221 | 0.1041 |

| Sub. | / Ratio | Wavelet Entropy | Hurst Exponent | DE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| 1 | 0.0156 | 0.0116 | 0.0167 | 0.0140 | 0.0218 | 0.0177 | 0.0411 | 0.0362 |

| 2 | 0.0118 | 0.0102 | 0.0174 | 0.0148 | 0.0222 | 0.0194 | 0.0257 | 0.0222 |

| 3 | 0.0191 | 0.0175 | 0.0161 | 0.0130 | 0.0171 | 0.0145 | 0.0136 | 0.0110 |

| 4 | 0.0125 | 0.0088 | 0.0116 | 0.0093 | 0.0128 | 0.0100 | 0.0401 | 0.0302 |

| 5 | 0.0307 | 0.0230 | 0.0280 | 0.0223 | 0.0337 | 0.0283 | 0.0256 | 0.0209 |

| 6 | 0.0195 | 0.0133 | 0.0241 | 0.0189 | 0.0312 | 0.0248 | 0.0332 | 0.0255 |

| 7 | 0.0124 | 0.0091 | 0.0169 | 0.0134 | 0.0109 | 0.0083 | 0.0261 | 0.0153 |

| 8 | 0.0101 | 0.0084 | 0.0419 | 0.0335 | 0.0172 | 0.0145 | 0.0231 | 0.0204 |

| 9 | 0.0084 | 0.0074 | 0.0771 | 0.0707 | 0.0400 | 0.0382 | 0.0215 | 0.0177 |

| 10 | 0.0152 | 0.0118 | 0.0163 | 0.0115 | 0.0177 | 0.0142 | 0.0194 | 0.0165 |

| 11 | 0.0234 | 0.0221 | 0.0203 | 0.0154 | 0.0128 | 0.0099 | 0.0415 | 0.0380 |

| 12 | 0.0154 | 0.0106 | 0.0239 | 0.0187 | 0.0199 | 0.0151 | 0.0158 | 0.0128 |

| 13 | 0.0109 | 0.0076 | 0.0149 | 0.0120 | 0.0126 | 0.0099 | 0.0160 | 0.0128 |

| 14 | 0.0212 | 0.0164 | 0.0240 | 0.0199 | 0.0214 | 0.0176 | 0.0283 | 0.0263 |

| 15 | 0.0274 | 0.0232 | 0.0144 | 0.0111 | 0.0166 | 0.0137 | 0.0224 | 0.0180 |

| 16 | 0.0171 | 0.0118 | 0.0166 | 0.0128 | 0.0136 | 0.0108 | 0.0355 | 0.0239 |

| 17 | 0.0209 | 0.0131 | 0.0270 | 0.0195 | 0.0099 | 0.0072 | 0.0224 | 0.0171 |

| 18 | 0.0210 | 0.0186 | 0.0148 | 0.0119 | 0.0277 | 0.0230 | 0.0204 | 0.0171 |

| 19 | 0.0163 | 0.0123 | 0.0182 | 0.0127 | 0.0247 | 0.0218 | 0.0191 | 0.0154 |

| 20 | 0.0196 | 0.0141 | 0.0196 | 0.0172 | 0.0244 | 0.0188 | 0.0426 | 0.0311 |

| 21 | 0.0080 | 0.0054 | 0.0106 | 0.0086 | 0.0123 | 0.0097 | 0.0113 | 0.0082 |

| 22 | 0.0429 | 0.0282 | 0.0156 | 0.0136 | 0.0134 | 0.0111 | 0.0139 | 0.0115 |

| 23 | 0.0379 | 0.0326 | 0.0400 | 0.0355 | 0.0336 | 0.0294 | 0.0549 | 0.0471 |

| Avg. | 0.0190 | 0.0147 | 0.0229 | 0.0187 | 0.0203 | 0.0168 | 0.0266 | 0.0215 |

| Sub. | / Band Power Ratio | Wavelet Entropy | Hurst Exponent | DE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| 1 | 0.0847 | 0.0846 | 0.0645 | 0.0645 | 0.0816 | 0.0811 | 0.0614 | 0.0575 |

| 2 | 0.0513 | 0.0434 | 0.0546 | 0.0465 | 0.0485 | 0.0401 | 0.0562 | 0.0463 |

| 3 | 0.0536 | 0.0480 | 0.0595 | 0.0465 | 0.0655 | 0.0686 | 0.0273 | 0.0234 |

| 4 | 0.0494 | 0.0414 | 0.0728 | 0.0618 | 0.0487 | 0.0388 | 0.0248 | 0.0207 |

| 5 | 0.1519 | 0.1287 | 0.2120 | 0.1889 | 0.1995 | 0.1711 | 0.1746 | 0.1570 |

| 6 | 0.1093 | 0.1014 | 0.1068 | 0.0982 | 0.1379 | 0.1234 | 0.1457 | 0.1382 |

| 7 | 0.0402 | 0.0328 | 0.0614 | 0.0514 | 0.0617 | 0.0492 | 0.0214 | 0.0170 |

| 8 | 0.0706 | 0.0604 | 0.1020 | 0.0832 | 0.0692 | 0.0567 | 0.0665 | 0.0529 |

| 9 | 0.1024 | 0.0671 | 0.1454 | 0.1019 | 0.0974 | 0.0740 | 0.0519 | 0.0352 |

| 10 | 0.2422 | 0.2215 | 0.3099 | 0.2672 | 0.2181 | 0.1942 | 0.2650 | 0.2406 |

| 11 | 0.0348 | 0.0290 | 0.0178 | 0.0144 | 0.0662 | 0.0595 | 0.0337 | 0.0302 |

| 12 | 0.0732 | 0.0647 | 0.0856 | 0.0712 | 0.1069 | 0.0920 | 0.0920 | 0.0827 |

| 13 | 0.0487 | 0.0401 | 0.0670 | 0.0562 | 0.0760 | 0.0657 | 0.0468 | 0.0357 |

| 14 | 0.3335 | 0.3112 | 0.3606 | 0.3035 | 0.2892 | 0.2423 | 0.2876 | 0.2601 |

| 15 | 0.1313 | 0.1313 | 0.1138 | 0.1127 | 0.0898 | 0.0878 | 0.1545 | 0.1545 |

| 16 | 0.1614 | 0.1286 | 0.1717 | 0.1394 | 0.1786 | 0.1370 | 0.1401 | 0.1099 |

| 17 | 0.0536 | 0.0482 | 0.0223 | 0.0178 | 0.0462 | 0.0420 | 0.0465 | 0.0405 |

| 18 | 0.0922 | 0.0908 | 0.0833 | 0.0820 | 0.0663 | 0.0643 | 0.1168 | 0.1157 |

| 19 | 0.0245 | 0.0201 | 0.0602 | 0.0547 | 0.0409 | 0.0335 | 0.0191 | 0.0165 |

| 20 | 0.0493 | 0.0457 | 0.0506 | 0.0472 | 0.0617 | 0.0560 | 0.0461 | 0.0413 |

| 21 | 0.0485 | 0.0406 | 0.0639 | 0.0530 | 0.0539 | 0.0435 | 0.0528 | 0.0486 |

| 22 | 0.0603 | 0.0561 | 0.0649 | 0.0612 | 0.1720 | 0.1661 | 0.0624 | 0.0589 |

| 23 | 0.1459 | 0.1332 | 0.1778 | 0.1618 | 0.1649 | 0.1345 | 0.1574 | 0.1519 |

| Avg. | 0.0971 | 0.0856 | 0.1099 | 0.0950 | 0.1061 | 0.0929 | 0.0935 | 0.0841 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Du, X.; Jiang, C.; Sun, J. Research on the Prediction of Driver Fatigue Degree Based on EEG Signals. Sensors 2025, 25, 7316. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237316

Wang Z, Du X, Jiang C, Sun J. Research on the Prediction of Driver Fatigue Degree Based on EEG Signals. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7316. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237316

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhanyang, Xin Du, Chengbin Jiang, and Junyang Sun. 2025. "Research on the Prediction of Driver Fatigue Degree Based on EEG Signals" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7316. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237316

APA StyleWang, Z., Du, X., Jiang, C., & Sun, J. (2025). Research on the Prediction of Driver Fatigue Degree Based on EEG Signals. Sensors, 25(23), 7316. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237316