A Low-Cost Passive Acoustic Toolkit for Underwater Recordings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hardware Components and Hydrophone Construction

2.2. Laboratory Recordings

2.3. Experimental Field Recordings

2.3.1. Recording Site 1: Marathonisi Islet at NMPZ

2.3.2. Recording Site 2: Agrilia

2.3.3. Recording Site 3: Mytilene Port

2.3.4. Recording Site 4: Villa

2.4. Acoustic Data Processing

3. Results

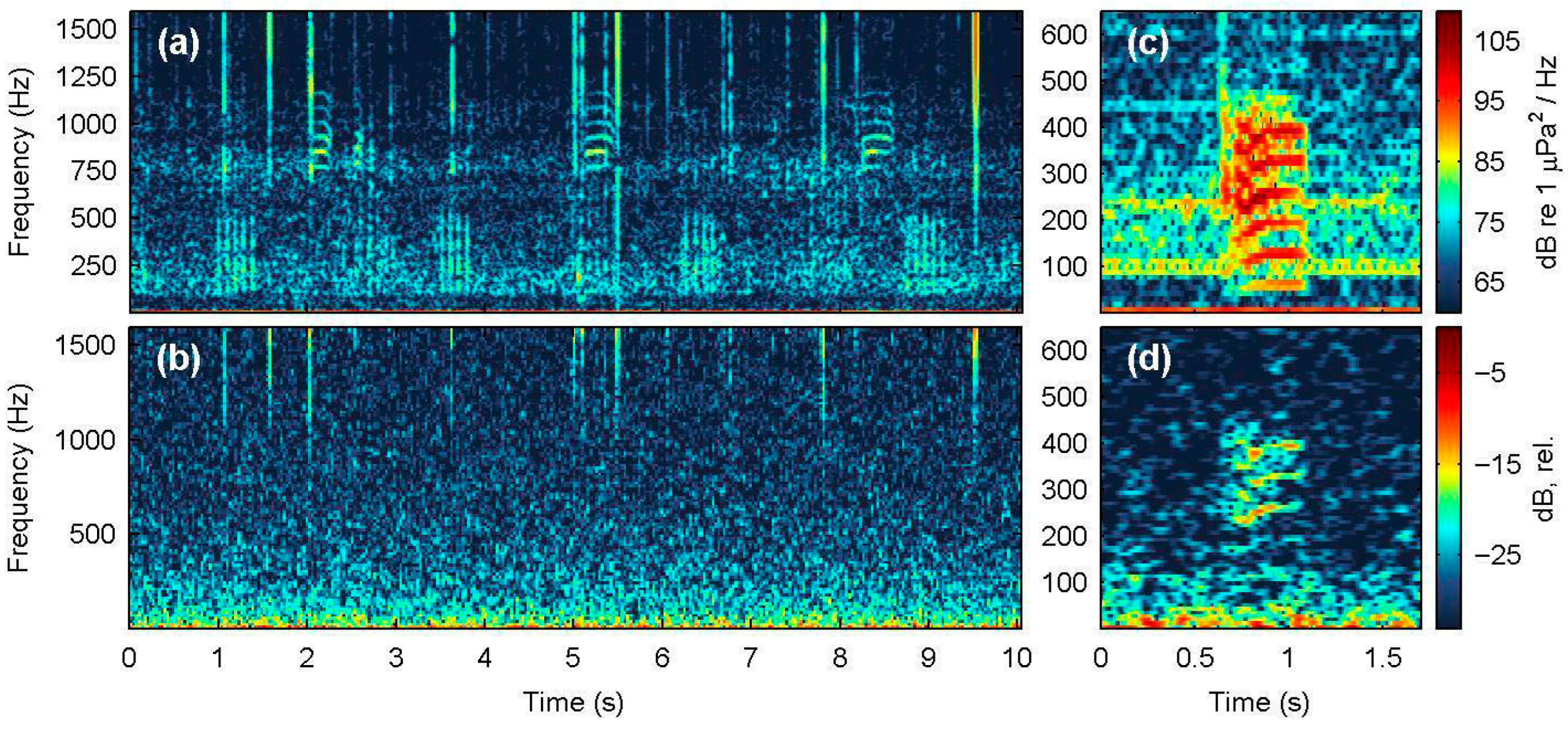

3.1. Water Tank Recordings of Artificial and Biological Signals

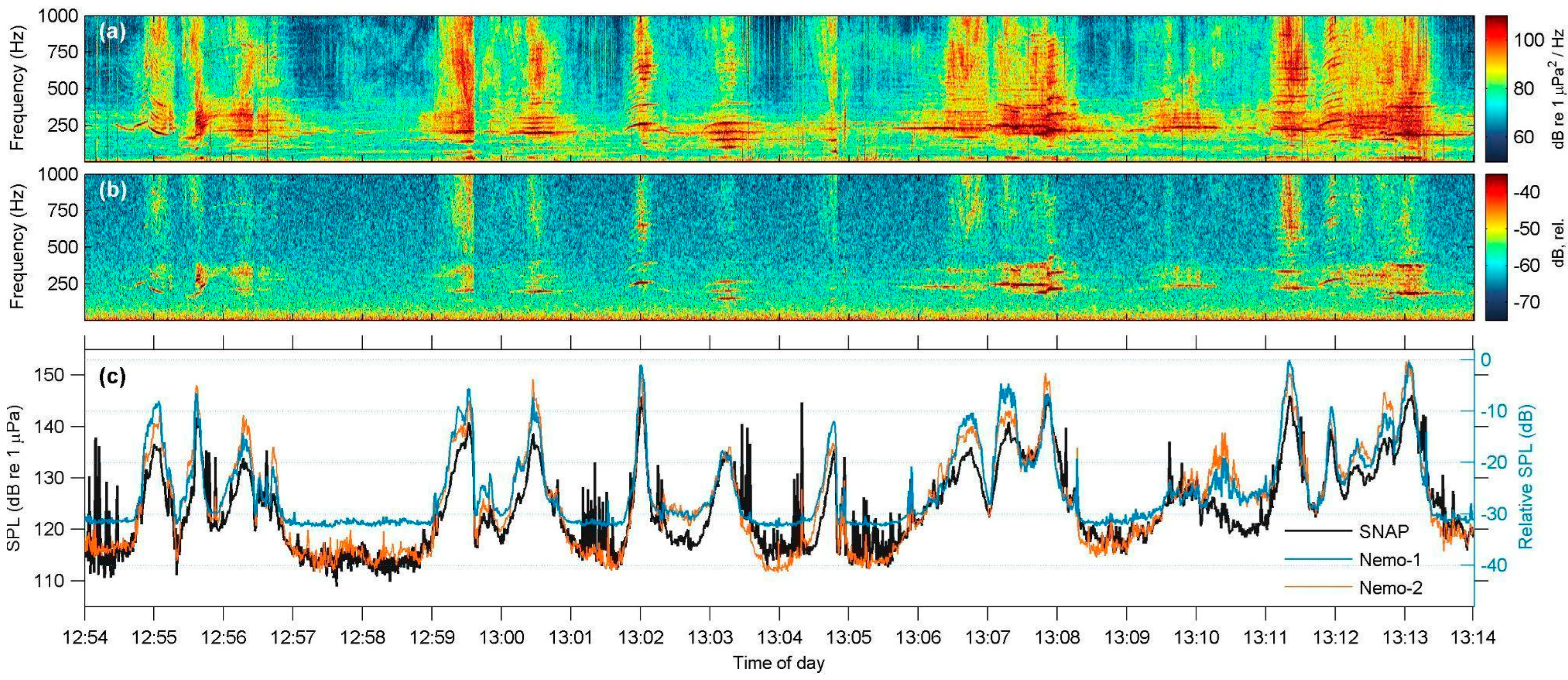

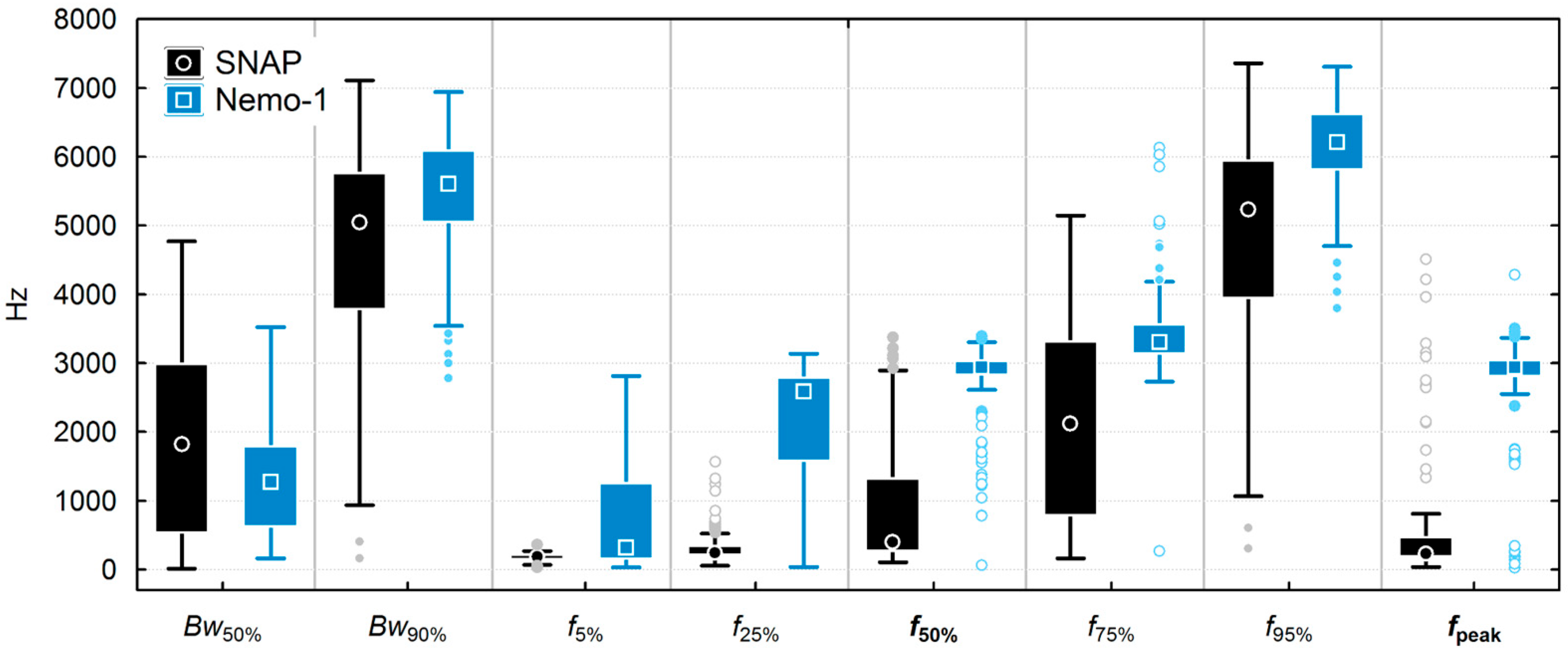

3.2. Recordings of Recreational Boat Traffic at NMPZ

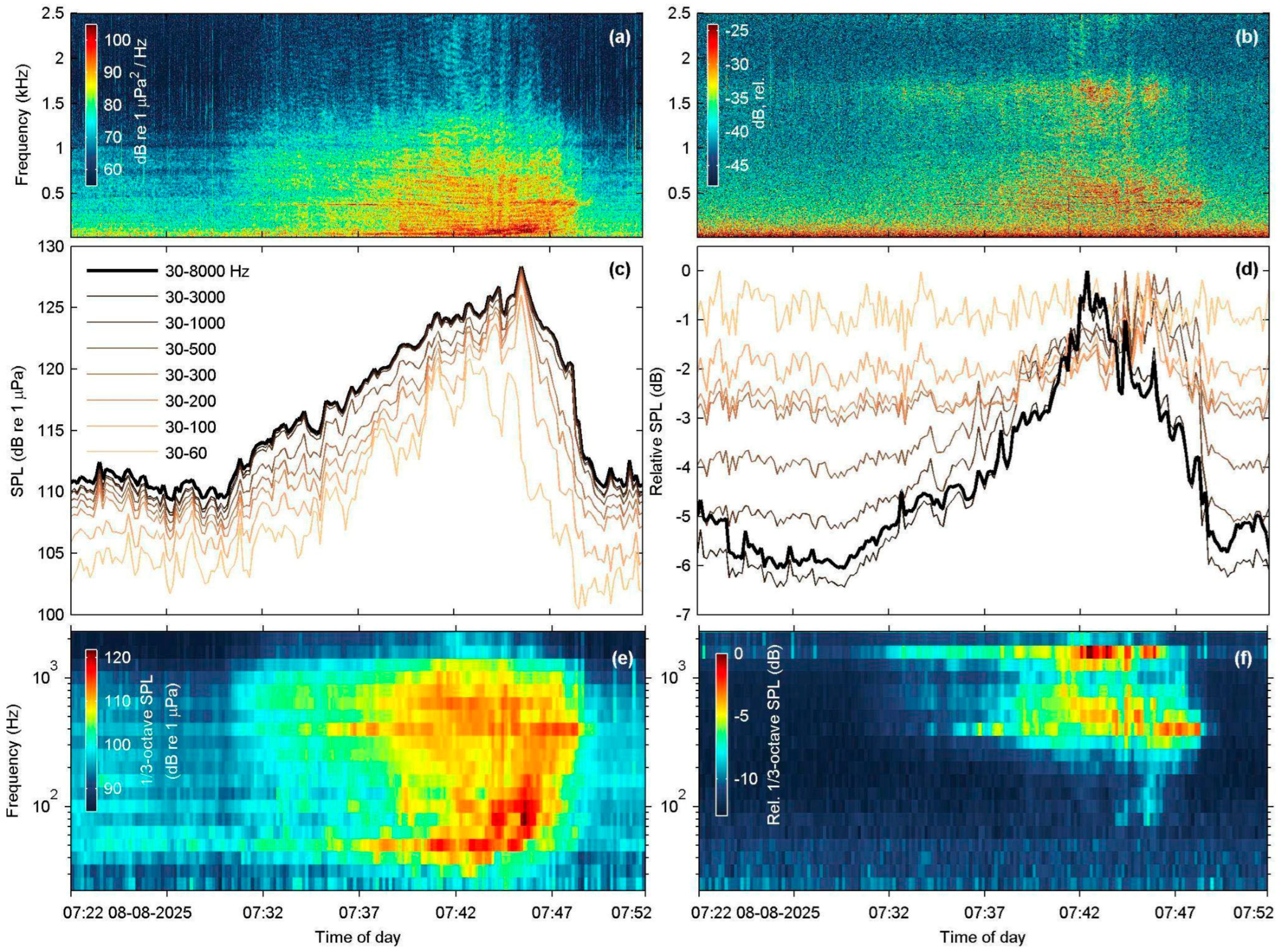

3.3. Recordings of Shipping Noise at Agrilia Site

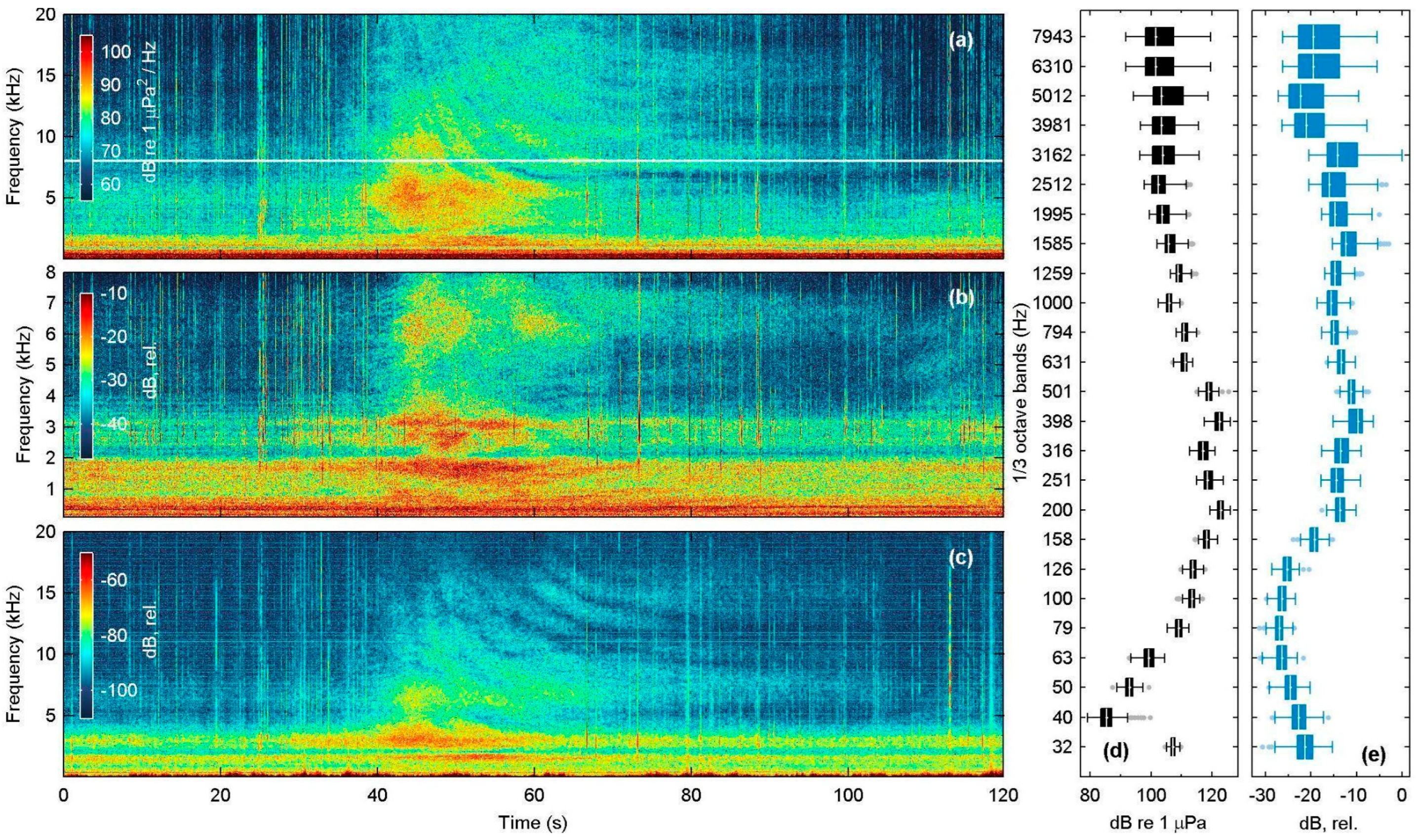

3.4. Recordings at Mytilene Port

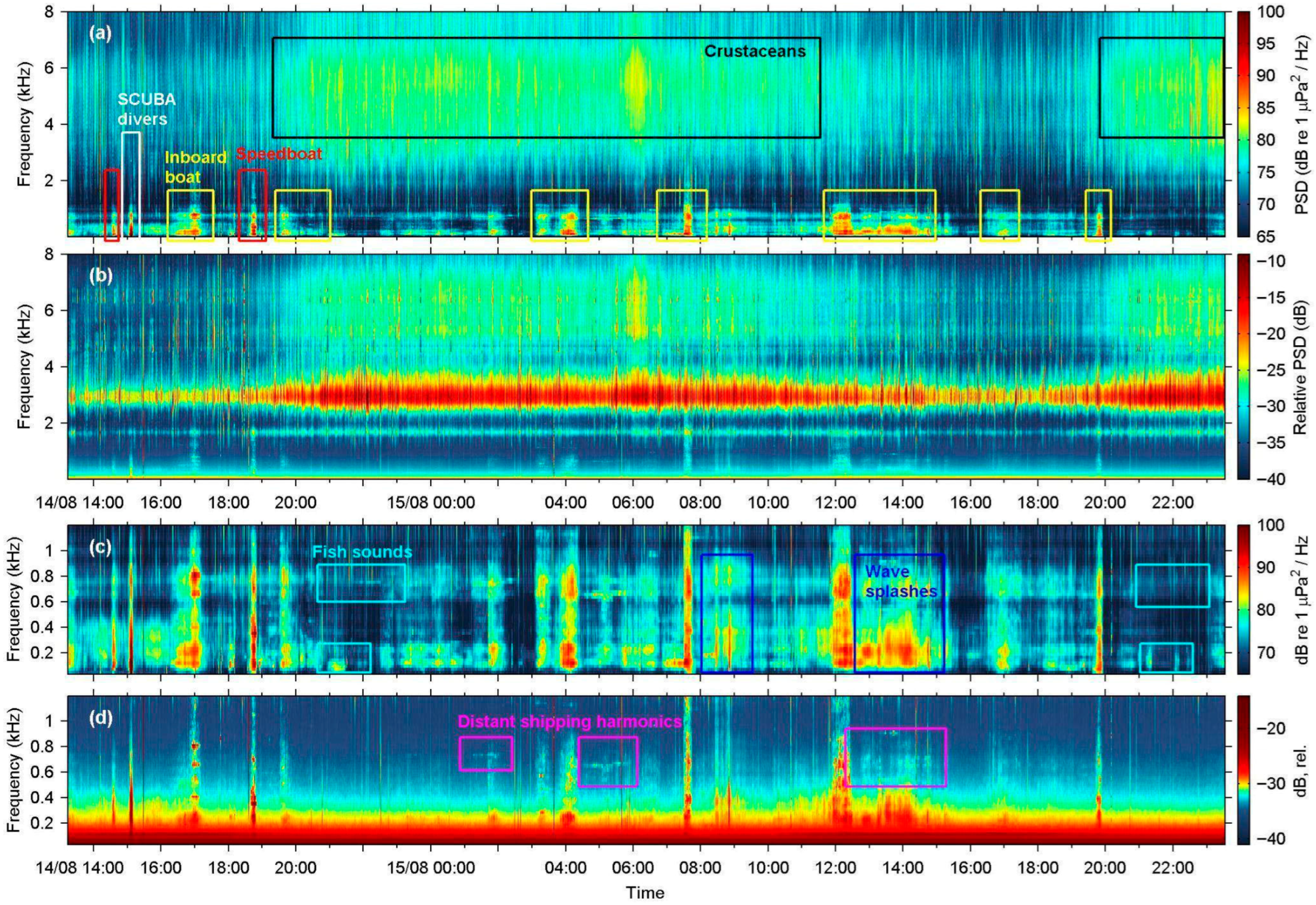

3.5. Long-Term Recordings of the Coastal Soundscape at Villa Site

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DIY | Do-it-yourself |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LTSA | Long term spectral average |

| MPA | Marine-protected area |

| MSFD | Marine Strategy Framework Directive |

| NMPZ | National Marine Park of Zakynthos |

| PAM | Passive acoustic monitoring |

| PSD | Power spectral density |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| PZ | Piezoelectric |

| RMS | Root-mean-square |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPL | Sound pressure level |

Appendix A

| Component | Function | Price (€) |

|---|---|---|

Piezoelectric disk (Bestar: FT-35T-2.6A1, 35 mm)

| Acts as the acoustic element of the device | 1.5/unit |

| Audio cable (10 m) | Connects the PZ disk to the recording device | 5/unit |

| ⌀60 mm plexiglass disk (4 mm) | Is attached to the PZ disk and acts as a lid to the hydrophone’s enclosure | 3/unit |

| PVC threaded nipple | Engulfs the acoustic element (housing) | 0.85/unit |

| Brass pipe fitting | Threaded on the PVC extension, it closes the recorder-side of the hydrophone and helps the audio cable exit the watertight enclosure. Additionally, its weight keeps the hydrophone submerged underwater | 6/unit |

| Heat shrink tubing * | Used for sealing and abrasion resistance at the point where the audio cable exits the enclosure | 0.15/m |

| Sikaflex-291i * | Used for sealing the front and back side of the hydrophone | 12/300 mL |

| Liquid teflon * | Used for sealing the connection between the brass fitting and the PVC thread | 11/100 mL |

| Teflon tape * | Used for sealing the connection between the brass fitting and the PVC thread | 0.5/10 m |

| Cyanoacrylate glue * | Used for attaching the PZ disk on the plexiglass disk, and for attaching the plexiglass disk on the PVC extension | 2.5/unit |

References

- Urick, R.J. Principles of Underwater Sound; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1983; p. 423. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J.C.; Radford, C.A. Marine bioacoustics. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R502–R507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, W.W.L.; Hastings, M.C. Principles of Marine Bioacoustics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 679. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, D.A.; Hawkins, A.D.; Jech, J.M. Active and passive acoustics to locate and study fish. In Fish Bioacoustics; Webb, J.F., Fay, R.R., Popper, A.N., Eds.; Springer Handbook of Auditory Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 279–309. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, M.C.P. Diversity of sound production in fish. Commun. Fishes 2006, 1, 71–104. [Google Scholar]

- Moulton, J.M.; McCauley, R.D.; Cato, D.H.; McDonald, M.A.; Jenner, C.M.; Jenner, M.N.; Jarman, W.M.; Mellinger, D.K.; Dunshea, G.; McCabe, K.A.; et al. The acoustics and acoustic behavior of the California spiny lobster, Panulirus interruptus. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2009, 125, 1783–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D. Mechanics of Underwater Noise; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976; p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, R.K.; Howe, B.M.; Mercer, J.A.; Dzieciuch, M.A. Ocean ambient sound: Comparing the 1960s with the 1990s for a receiver off the California coast. Acoust. Res. Lett. Online 2002, 3, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkinshaw, H.M. Measurements of ambient noise spectra in the South Norwegian Sea. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2005, 30, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.A. Anthropogenic and natural sources of ambient noise in the ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 395, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Chapuis, L.; Collin, S.P.; Costa, D.P.; Devassy, R.P.; Eguiluz, V.M.; Erbe, C.; Gordon, T.A.C.; Halpern, B.S.; Harding, H.R.; et al. The Soundscape of the Anthropocene Ocean. Science 2021, 371, eaba4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, P.H.; Miller, J.H.; Cato, D.H.; Andrew, R.K. Underwater ambient noise. Acoust. Today 2007, 3, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, A.D.; Popper, A.N. A sound approach to assessing the impact of underwater noise on marine fishes and invertebrates. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, C.; Marley, S.A.; Schoeman, R.P.; Smith, J.N.; Trigg, L.E.; Embling, C.B. The Effects of Ship Noise on Marine Mammals—A Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabbekoorn, H.; Bouton, N.; van Opzeeland, I.; Coers, A.; ten Cate, C.; Popper, A.N. A Noisy Spring: The Impact of Globally Rising Underwater Sound Levels on Fish. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.V.; Wrede, A.; Tremblay, N.; Beermann, J. Low-frequency noise pollution impairs burrowing activities of marine benthic invertebrates. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 310, 119899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solan, M.; Hauton, C.; Godbold, J.A.; Wood, C.L.; Leighton, T.G.; White, P. Anthropogenic sources of underwater sound can modify how sediment-dwelling invertebrates mediate ecosystem properties. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008, establishing a framework for community action in the field of marine environmental policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive). Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, L164, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, N.D.; Putland, R.L.; André, M.; Baudin, E.; Felli, M.; Slabbekoorn, H.; Dekeling, R.P.A. A decade of underwater noise research in support of the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 228, 106299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciulin, M.; Petrizzo, A.; Madricardo, F.; Barbanti, A.; Bastianini, M.; Biagiotti, I.; Bosi, S.; Centurelli, M.; Codarin, A.; Costantini, I.; et al. First basin scale spatial–temporal characterization of underwater sound in the Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Manna, G.; Picciulin, M.; Crobu, A.; Perretti, F.; Ronchetti, F.; Manghi, M.; Ruiu, A.; Ceccherelli, G. Marine soundscape and fish biophony of a Mediterranean marine protected area. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrias, V.; De Lucia, G.A.; Filiciotto, F.; Ronchetti, F.; Manghi, M.; Ruiu, A.; Ceccherelli, G. Marine soundscape and its temporal acoustic characterisation in the Gulf of Oristano, Sardinia (Western Mediterranean Sea). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2023, 24, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, C.; Sini, M.; Trygonis, V.; Gerovasileiou, V.; Sourbès, L.; Koutsoubas, D. Assessment of fish communities in a Mediterranean MPA: Can a seasonal no-take zone provide effective protection? Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 207, 106299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.E.; Halpern, B.S. Biological responses in marine no-take reserves versus partially protected areas. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 367, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscaino, G.; Ceraulo, M.; Pieretti, N.; Corrias, V.; Farina, A.; Filiciotto, F.; Maccarrone, V.; Grammauta, R.; Caruso, F.; Giuseppe, A.; et al. Temporal patterns in the soundscape of the shallow waters of a Mediterranean marine protected area. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L. Rethinking the design of marine protected areas in coastal habitats. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 213, 117642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M.F.; Rowell, T.J.; Margolina, T.; Baumann-Pickering, S.; Solsona-Berga, A.; Adams, J.D.; Joseph, J.; Kim, E.B.; Kok, A.C.M.; Kügler, A.; et al. Understanding vessel noise across a network of marine protected areas. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haver, S.M.; Fournet, M.E.H.; Dziak, R.P.; Gabriele, C.; Gedamke, J.; Hatch, L.T. Comparing the underwater soundscapes of four U.S. National Parks and Marine Sanctuaries. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCordic, J.A.; DeAngelis, A.I.; Kline, L.R.; McBride, C.; Rodgers, G.G.; Rowell, T.J.; Smith, J.; Stanley, J.A.; Stokoe, A.; Van Parijs, S.M. Biological sound sources drive soundscape characteristics of two Australian marine parks. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 669412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinger, D.K.; Stafford, K.M.; Moore, S.E.; Dziak, R.P.; Matsumoto, H. An overview of fixed passive acoustic observation methods for cetaceans. Oceanography 2007, 20, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Širović, A.; Cutter, G.R.; Butler, J.L.; Demer, D.A. Rockfish sounds and their potential use for population monitoring in the Southern California Bight. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2009, 66, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heenehan, H.L.; Van Parijs, S.M.; Bejder, L.; Tyne, J.A.; Southall, B.L.; Southall, H.; Johnston, D.W. Natural and anthropogenic events influence the soundscapes of four bays on Hawaii Island. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 124, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awbery, T.; Akkaya, A.; Lyne, P.; Rudd, L.; Hoogenstrijd, G.; Nedelcu, M.; Kniha, D.; Erdoğan, M.A.; Persad, C.; Amaha Öztürk, A.; et al. Spatial Distribution and Encounter Rates of Delphinids and Deep Diving Cetaceans in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea of Turkey and the Extent of Overlap With Areas of Dense Marine Traffic. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 860242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogou, N.; Klinck, H.; Frantzis, A.; Nystuen, J.A.; Papathanassiou, E.; Katsanevakis, S. Year-round acoustic presence of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) and baseline ambient ocean sound levels in the Greek Seas. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2019, 20, 18769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trygonis, C.; Gerstein, E.; Moir, J.; McCulloch, S. Vocalization characteristics of North Atlantic right whale surface active groups in the calving habitat, southeastern United States. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 134, 4518–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laran, S.; Drouot-Dulau, V. Seasonal variation of striped dolphins, fin- and sperm whales’ abundance in the Ligurian Sea (Mediterranean Sea). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2007, 87, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, T.A.C. HydroMoth: Testing a prototype low-cost acoustic recorder for monitoring aquatic soundscapes. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 8, e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, R.; Di Nardo, F.; Lucchetti, A.; Virgili, M.; Petetta, A.; Veli, D.L.; Screpanti, L.; Bartolucci, V.; Scaradozzi, D. The development of a low-cost hydrophone for passive acoustic monitoring of dolphin’s vocalizations. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Vivas, E.; León López, B. Construction, calibration, and field test of a home-made, low-cost hydrophone system for cetacean acoustic research. In Proceedings of the 160th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, Cancun, Mexico, 15–19 November 2010; Volume 11, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Galanos, V.; Trygonis, V. Construction of low-cost hydrophones using off-the-shelf components. In Proceedings of the 4th International Congress on Applied Ichthyology, Oceanography & Aquatic Environment (HydroMediT), Mytilene, Lesvos, Greece, 4–6 November 2021; pp. 547–548. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson, A.D.; Lepper, P. A simple hydrophone monitor for cetacean acoustics. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Lugano, Switzerland, 9–11 February 1995; pp. 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakou, K.; Katsanevakis, S.; Trygonis, V. Quantitative analysis of the acoustic repertoire of free-ranging bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in N Aegean, Greece, recorded in the vicinity of aquaculture net pens. In Proceedings of the 14th International Congress on the Zoogeography and Ecology of Greece and Adjacent Regions (ICZEGAR), Thessaloniki, Greece, 27–30 June 2019; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini, V.; Pergent-Martini, C.; Pergent, G.; Agreil, M.; Skoufas, G.; Sourbes, L.; Tsirika, A. Use of SPOT 5 for mapping seagrasses: An application to Posidonia oceanica. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 94, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavas, N.; Georghiou, K.; Arianoutsou, M.; Dimopoulos, D. Vegetation and sand characteristics influencing nesting activity of Caretta caretta on Sekania beach. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 121, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritoulis, D. Nesting activity and reproductive output of loggerhead sea turtles, Caretta caretta, over 19 seasons (1984–2002) at Laganas Bay, Zakynthos, Greece: The largest rookery in the Mediterranean. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2005, 4, 916–929. [Google Scholar]

- Togridou, A.; Hovardas, T.; Pantis, J.D. Determinants of visitors’ willingness to pay for the National Marine Park of Zakynthos, Greece. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 60, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciulin, M.; Calcagno, G.; Sebastianutto, L.; Bonacito, C.; Codarin, A.; Costantini, M.; Ferrero, E.A.; Hawkins, A.D. Diagnostics of nocturnal calls of Sciaena umbra (L., fam. Sciaenidae) in a nearshore Mediterranean marine reserve. Bioacoustics 2013, 22, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertucci, F.; Lejeune, P.; Payrot, J.; Parmentier, E. Sound production by dusky grouper Epinephelus marginatus at spawning aggregation sites. J. Fish Biol. 2015, 87, Article 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolgan, M.; Soulard, J.; Di Iorio, L.; Gervaise, C.; Lejeune, P.; Gobert, S.; Parmentier, E. Sea chordophones make the mysterious /Kwa/ sound: Identification of the emitter of the dominant fish sound in Mediterranean seagrass meadows. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, jeb196931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven Pro: Interactive Sound Analysis Software, Version 1.6.4; K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2023.

- Merchant, N.D.; Fristrup, K.M.; Johnson, M.P.; Tyack, P.L.; Witt, M.J.; Blondel, P.; Parks, S.E. Measuring acoustic habitats. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura, T.; Akamatsu, T.; Yan, H.Y. Analyses of small tank acoustics: Empirical and theoretical approaches. Bioacoustics 2002, 12, 330–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Parijs, S.M.; Clark, C.W.; Sousa-Lima, R.S.; Parks, S.E.; Rankin, S.; Risch, D.; Van Opzeeland, I.C. Management and research applications of real-time and archival passive acoustic sensors over varying temporal and spatial scales. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 395, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyack, P.L.; Clark, C.W. Communication and acoustical behavior in dolphins and whales. In Hearing by Whales and Dolphins; Au, W.W.L., Popper, A.N., Fay, R.R., Eds.; Springer Handbook of Auditory Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 156–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladich, F. Ecology of sound communication in fishes. Fish Fish. 2019, 20, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, B. Bioacoustics, habitat ambience in ecological balance. Whole Earth Rev. 1987, 57, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, A.; Ceraulo, M. The acoustic chorus and its ecological significance. In Ecoacoustics: The Ecological Role of Sounds; Farina, A., Gage, S.H., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basan, F.; Fischer, J.-G.; Putland, R.; Brinkkemper, J.; de Jong, C.A.F.; Binnerts, B.; Norro, A.; Kühnel, D.; Ødegaard, L.-A.; Andersson, M.; et al. The underwater soundscape of the North Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrbenac, A. Overview of Underwater Anthropogenic Noise, Impacts on Marine Biodiversity and Mitigation Measures in the South-Eastern European part of the Mediterranean, Focussing on Seismic Surveys; Report Commissioned by OceanCare: Croatia; OceanCare: Waedenswil, Switzerland, 2017; 75p. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, J.A. Impacts of anthropogenic sound. In Marine Mammal Research: Conservation beyond Crisis; Reynolds, J.E., Perrin, W.F., Reeves, R.R., Montgomery, S., Ragen, T.J., Eds.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005; pp. 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, M.F.; Stafford, K.M.; Latha, G. Near real-time underwater passive acoustic monitoring of natural and anthropogenic sounds. In Observing the Oceans in Real Time; Venkatesan, R., Tandon, A., D’Asaro, E., Atmanand, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, V.O.; Alford, R.S.; Emling, J.W. Underwater ambient noise. J. Mar. Res. 1948, 7, 410–429. [Google Scholar]

- Wenz, G.M. Acoustic ambient noise in the ocean: Spectra and sources. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1962, 34, 1936–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cato, D.H.; Tavener, S. Ambient sea noise dependence on local, regional and geostrophic wind speeds: Implications for forecasting noise. Appl. Acoust. 1997, 51, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.B.; Nystuen, J.A.; Lien, R.-C. Prediction of underwater sound levels from rain and wind. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005, 117, 3555–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, I.T.; van Opzeeland, I. Using acoustic metrics to characterize underwater acoustic biodiversity in the Southern Ocean. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 6, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minello, M. Ecoacoustic indices in marine ecosystems: A review on recent developments and applications. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 78, 3066–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijanowski, B.C.; Villanueva-Rivera, L.J.; Dumyahn, S.L.; Farina, A.; Krause, B.L.; Napoletano, B.M.; Gage, S.H.; Pieretti, N. Soundscape ecology: The science of sound in the landscape. Bioscience 2011, 61, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18405:2017; Underwater Acoustics—Terminology. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–51.

- Haren, A.M. Reducing noise pollution from commercial shipping in the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary: A case study in marine protected area management of underwater noise. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2007, 10, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Erbe, C.; Ashe, E.; Clark, C.W. Quiet(er) marine protected areas. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiggins, S.M.; Hildebrand, J.A.; Brager, E.; Woolhiser, B. High-frequency Acoustic Recording Package (HARP) for broad-band, long-term marine mammal monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2007 Symposium on Underwater Technology and Workshop on Scientific Use of Submarine Cables and Related Technologies, Tokyo, Japan, 17–19 April 2007; IEEE: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; pp. 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putland, R.L.; de Jong, C.A.F.; Binnerts, B.; Farcas, A.; Merchant, N.D. Multi-site validation of shipping noise maps using field measurements. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 179, 113733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janik, V.M. Source levels and the estimated active space of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) whistles in the Moray Firth, Scotland. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2000, 186, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrimger, P.; Heitmeyer, R.M. Acoustic source-level measurements for a variety of merchant ships. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1991, 89, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermannsen, L.; Tougaard, J.; Beedholm, K.; Nabe-Nielsen, J.; Madsen, P.T. Characteristics and propagation of airgun pulses in shallow water with implications for effects on small marine mammals. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridley, T.; Berggren, P.; Cockcroft, V.; Janik, V.M. The acoustic repertoire of wild common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Walvis Bay, Namibia. Bioacoustics 2015, 24, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.F.; Monteiro-Filho, E.L.A.; Oliveira, L.R.; Costa, M.F. Characteristics of whistles from resident bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the South Atlantic Ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007, 121, 2278–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, B.; Hedwig, D.; Trygonis, V.; Gerstein, E. Classification of Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) vocalizations. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 147, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrier, I.; Huetz, C.; Prévost, L.; Dendrinos, P.; Karamanlidis, A.A. First Description of the Underwater Sounds in the Mediterranean Monk Seal Monachus monachus in Greece: Towards Establishing a Vocal Repertoire. Animals 2023, 13, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, A.C.; Menna, B.V.; Cabreira, A.G.; Rodriguez, D.H.; Saubidet, A.; Olguin, J.; Giardino, G.V. Validation of low-cost hydrophones for acoustic detection of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus truncatus) in a controlled environment. Mar. Fish. Sci. 2025, 38, 11005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, B.A.; Ramos, E.A.; Lasala, J.A.; Ferrell, Z.N.R.; Kaney, N.A.; Martinez, E.; Areolla Illescas, M.R.; Arena, J. Captive male and female West Indian manatees display variable vocal and behavioral responses to playbacks of conspecifics. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2025, 41, e70038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouy, X.; Black, M.; Cox, K.; Qualley, J.; Dosso, S.; Juanes, F. Identification of fish sounds in the wild using a set of portable audio-video arrays. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollara, A.; Sutin, A.; Salloum, H. Passive acoustic methods of small boat detection, tracking and classification. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland Security (HST 2017), Waltham, MA, USA, 25–26 April 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuis, L.; Burca, M.; Gridley, T.; Mouy, X.; Nath, A.; Nedelec, S.; Roberts, M.; Seeyave, S.; Theriault, J.; Urban, E.; et al. Development of a low-cost hydrophone for research, education, and community science. In Proceedings of the One Ocean Science Congress 2025, Nice, France, 3–6 June 2025; p. OOS2025-71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saheban, H.; Kordrostami, Z. Hydrophones, fundamental features, design considerations, and various structures: A review. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 329, 112790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Lima, R.; Fernandes, D.P. A review and inventory of fixed autonomous recorders for passive acoustic monitoring of marine mammals: 2013 state-of-the-industry. Aquat. Mamm. 2013, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Coordinates | Date | Depth (m) 1 | Rt (min) | Device | Recorder | fs (kHz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marathonisi | 37.68703° N 20.86630° E | 26-06-2025 | 3 (3) | 180 | Nemo-1 | Philips | 16 |

| Nemo-2 | Tascam | 48 | |||||

| SNAP | (embedded) | 48 | |||||

| Agrilia | 39.00706° N 26.60246° E | 08-08-2025 | 7 (35) | 60 | Nemo-1 | Philips | 16 |

| Nemo-2 | M-Audio | 48 | |||||

| SNAP | (embedded) | 96 | |||||

| Mytilene port | 39.10287° N 26.55898° E | 10-06-2025 | 4 (4) | 30 | Nemo-1 | Philips | 16 |

| Nemo-2 | Tascam | 44.1 | |||||

| SNAP | (embedded) | 48 | |||||

| Villa | 39.01329° N 26.55154° E | 14/15-08-2025 | 6 (6) | 2060 | Nemo-1 | Philips | 16 |

| Nemo-2 | M-Audio | 44.1 | |||||

| SNAP | (embedded) | 96 |

| Descriptor | Statistic | SNAP | Nemo-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90% Duration | Mean ± SD | 23.3 ± 14.1 | 21.2 ± 14.3 |

| dt90% (s) | Range | 4.6–113.3 | 3.5–111.3 |

| IQR | 15.4–27.0 | 12.9–25.3 | |

| 90% Bandwidth | Mean ± SD | 4467 ± 1455 | 5484 ± 822 |

| Bw90% (Hz) | Range | 164–7113 | 2781–6945 |

| IQR | 3785–5766 | 5055–6086 | |

| 95% Frequency | Mean ± SD | 4838 ± 1476 | 6155 ± 626.2 |

| f95% (Hz) | Range | 305–7359 | 3797–7312 |

| IQR | 3949–5941 | 5812–6617 | |

| Peak frequency | Mean ± SD | 502 ± 765 | 2626 ± 894 |

| fpeak (Hz) | Range | 35–4512 | 31–4289 |

| IQR | 187–469 | 2812–3039 | |

| Center frequency | Mean ± SD | 856 ± 803 | 2802 ± 503 |

| f50% (Hz) | Range | 105–3375 | 62–3398 |

| IQR | 269–1324 | 2836–3031 | |

| 5% frequency | Mean ± SD | 170 ± 59 | 671 ± 632 |

| f5% (Hz) | Range | 35–363 | 31–2812 |

| IQR | 152–211 | 156–1258 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galanos, V.; Trygonis, V.; Mazaris, A.D.; Katsanevakis, S. A Low-Cost Passive Acoustic Toolkit for Underwater Recordings. Sensors 2025, 25, 7306. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237306

Galanos V, Trygonis V, Mazaris AD, Katsanevakis S. A Low-Cost Passive Acoustic Toolkit for Underwater Recordings. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7306. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237306

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalanos, Vassilis, Vasilis Trygonis, Antonios D. Mazaris, and Stelios Katsanevakis. 2025. "A Low-Cost Passive Acoustic Toolkit for Underwater Recordings" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7306. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237306

APA StyleGalanos, V., Trygonis, V., Mazaris, A. D., & Katsanevakis, S. (2025). A Low-Cost Passive Acoustic Toolkit for Underwater Recordings. Sensors, 25(23), 7306. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237306