Hydrostatic Water Displacement Sensing for Continuous Biogas Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

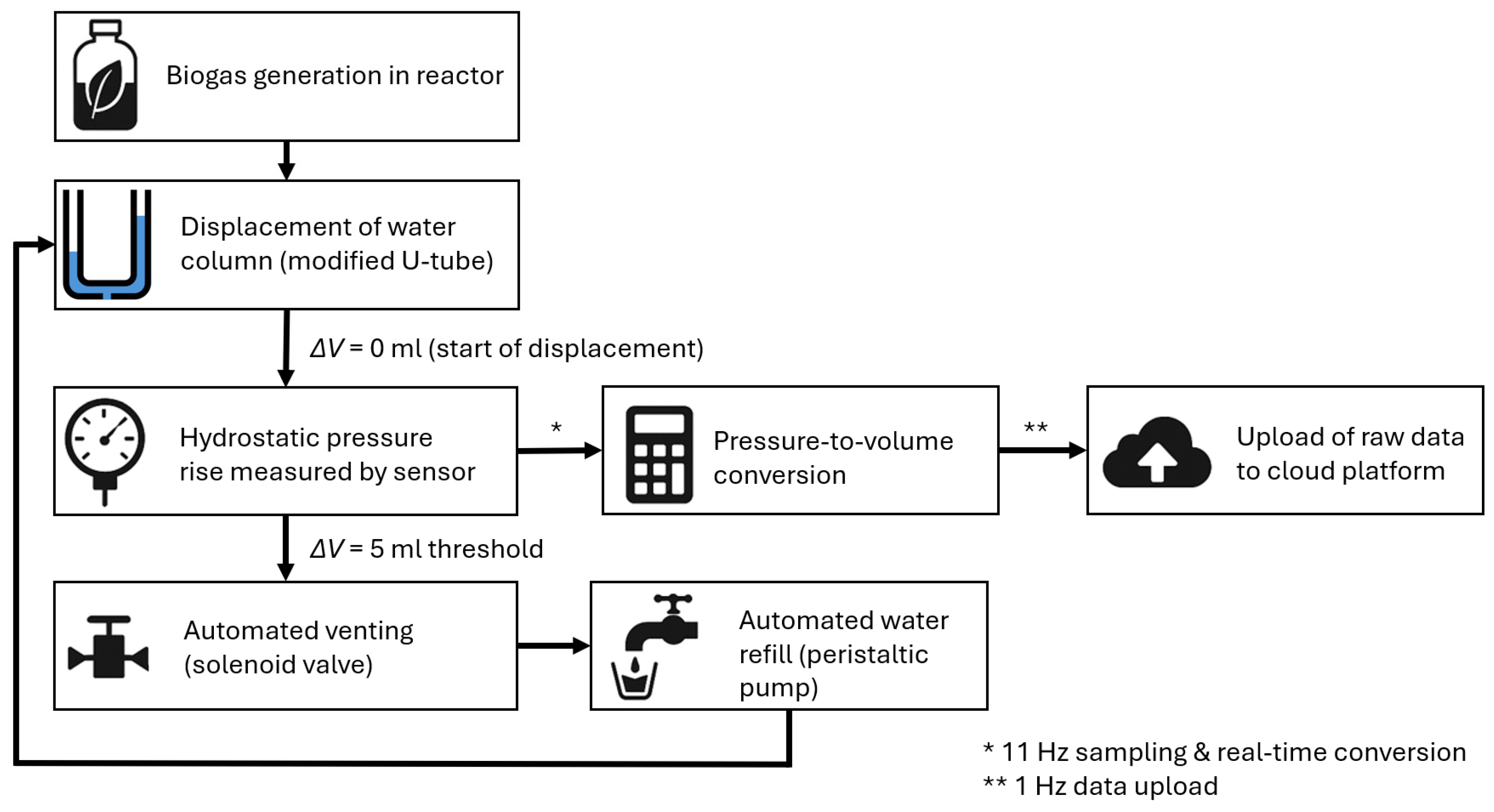

2.1. Concept of Automated Biogas Production Measurement

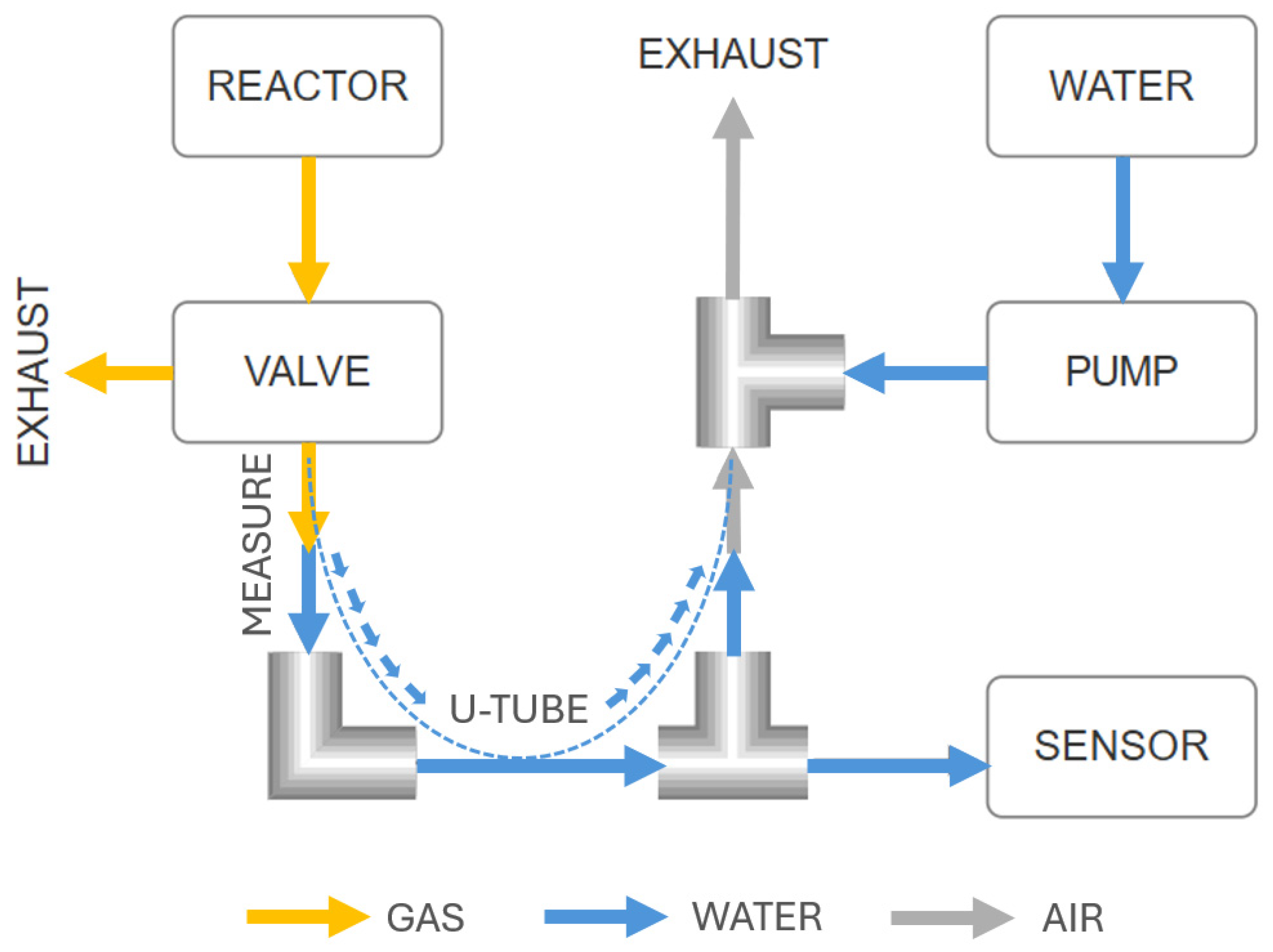

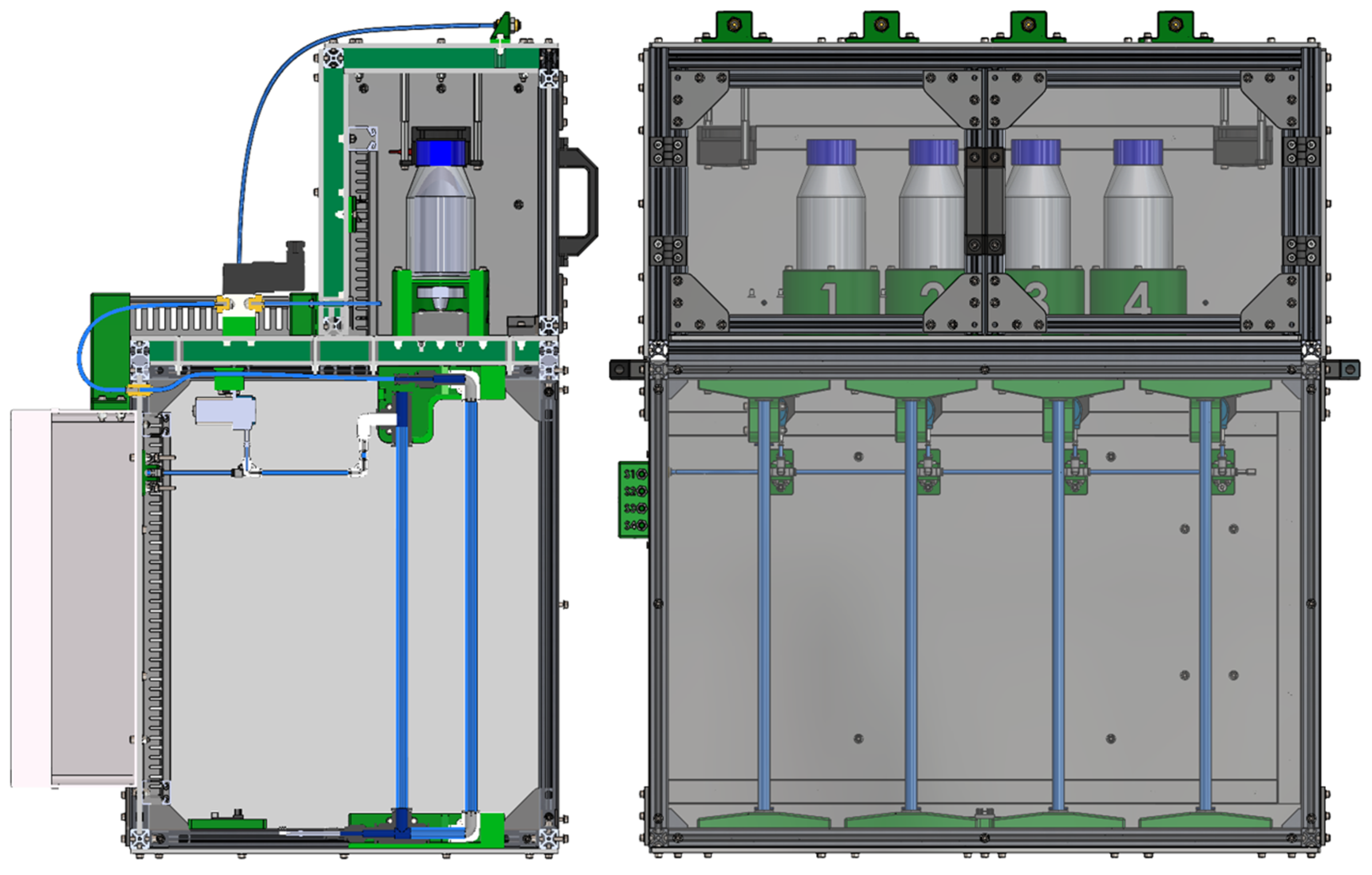

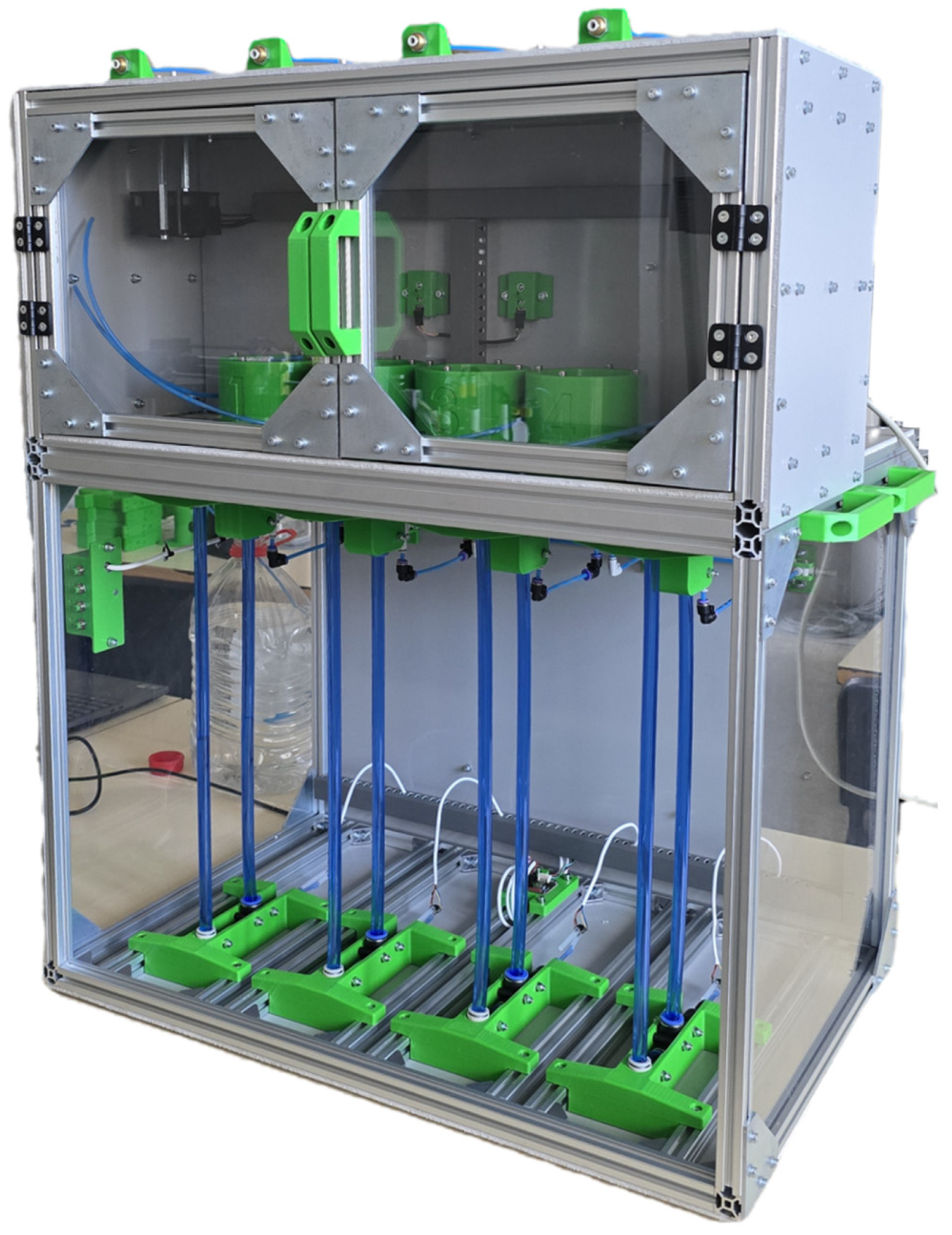

2.2. Mechanical and Fluidic Architecture of the System

- Gas accumulation and rise in the liquid level;

- Automatic venting of gas through an electromagnetic valve;

- Level inspection and correction.

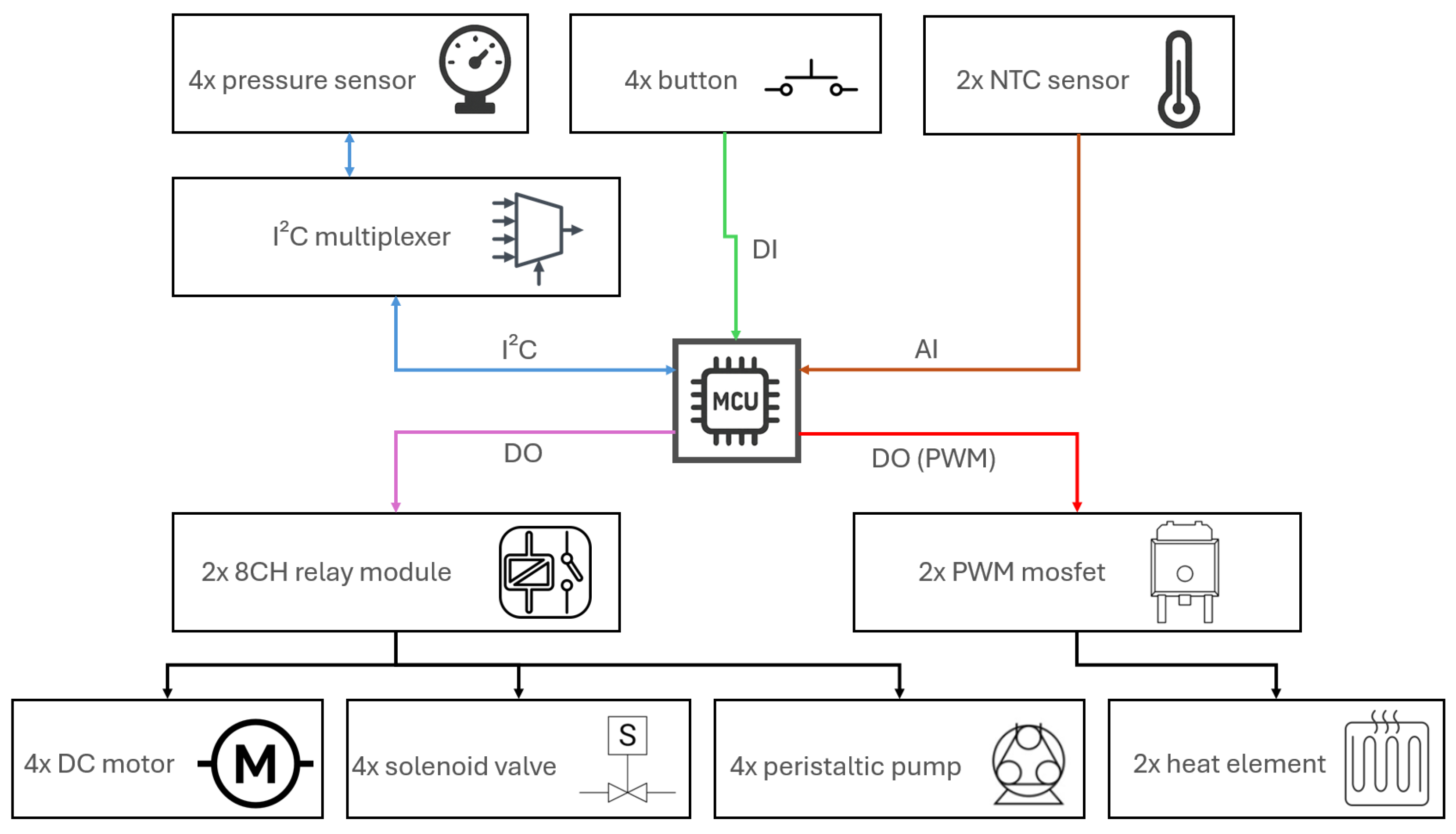

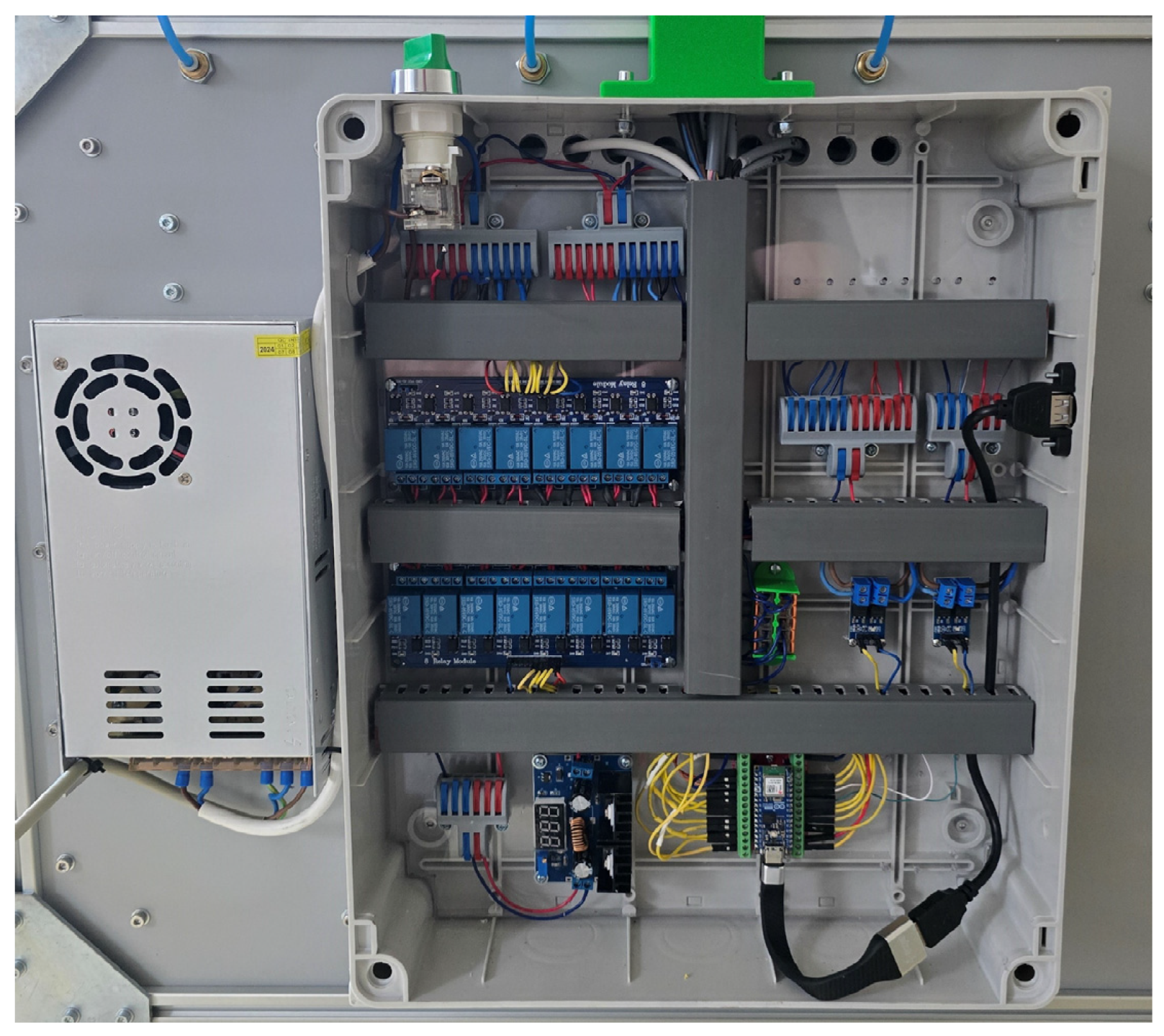

2.3. Sensors and Control Electronics Used

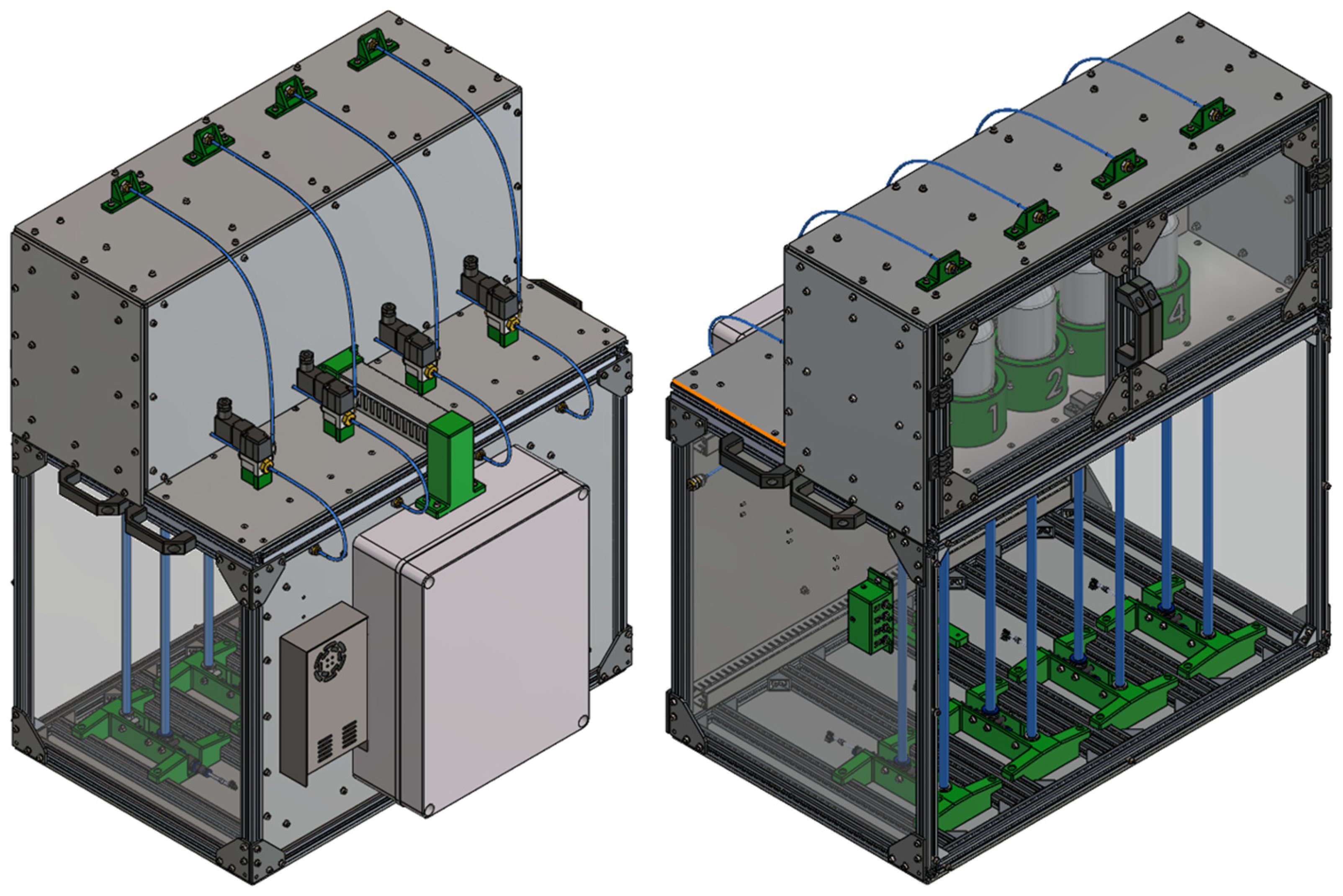

2.4. Mechanical Design of the Device

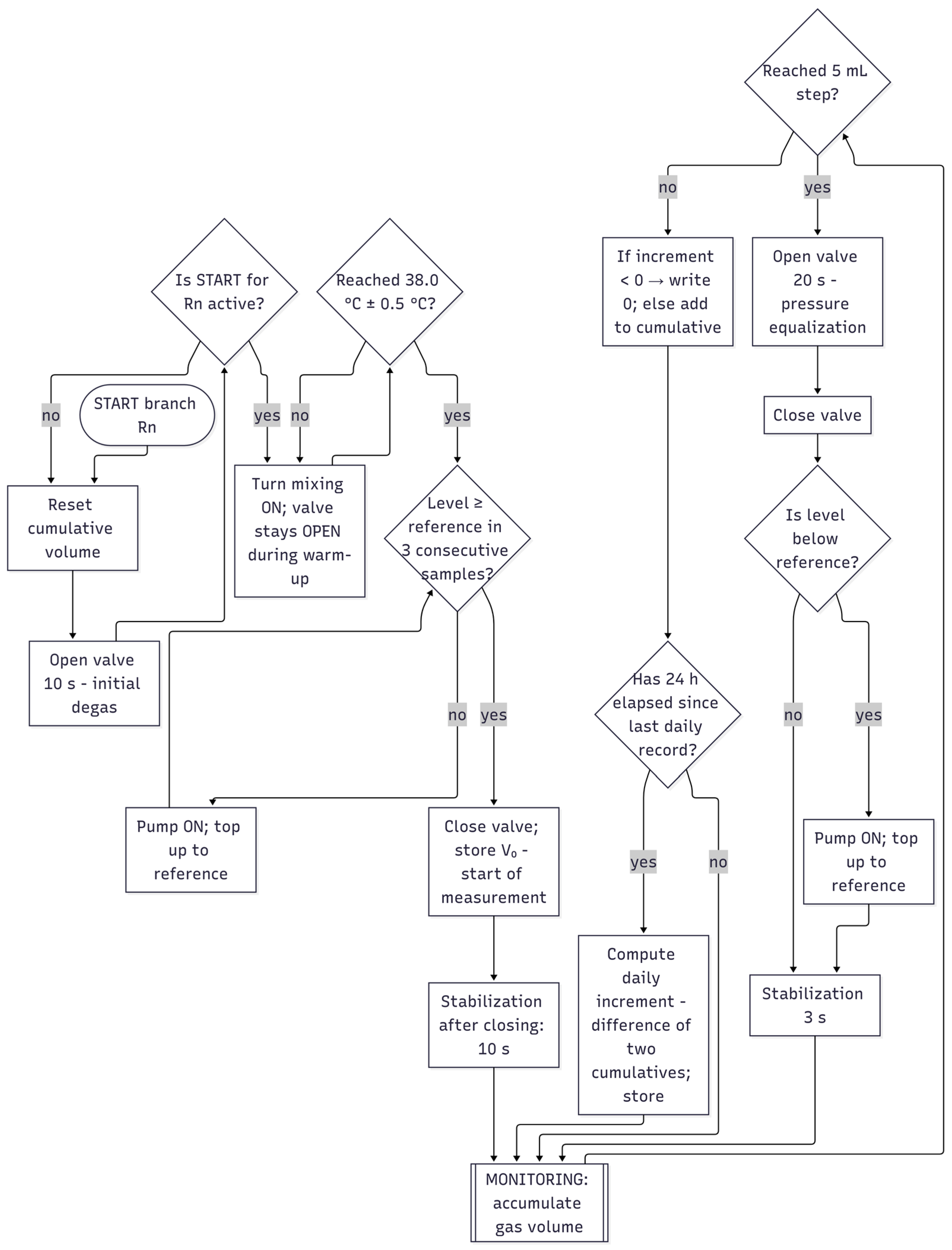

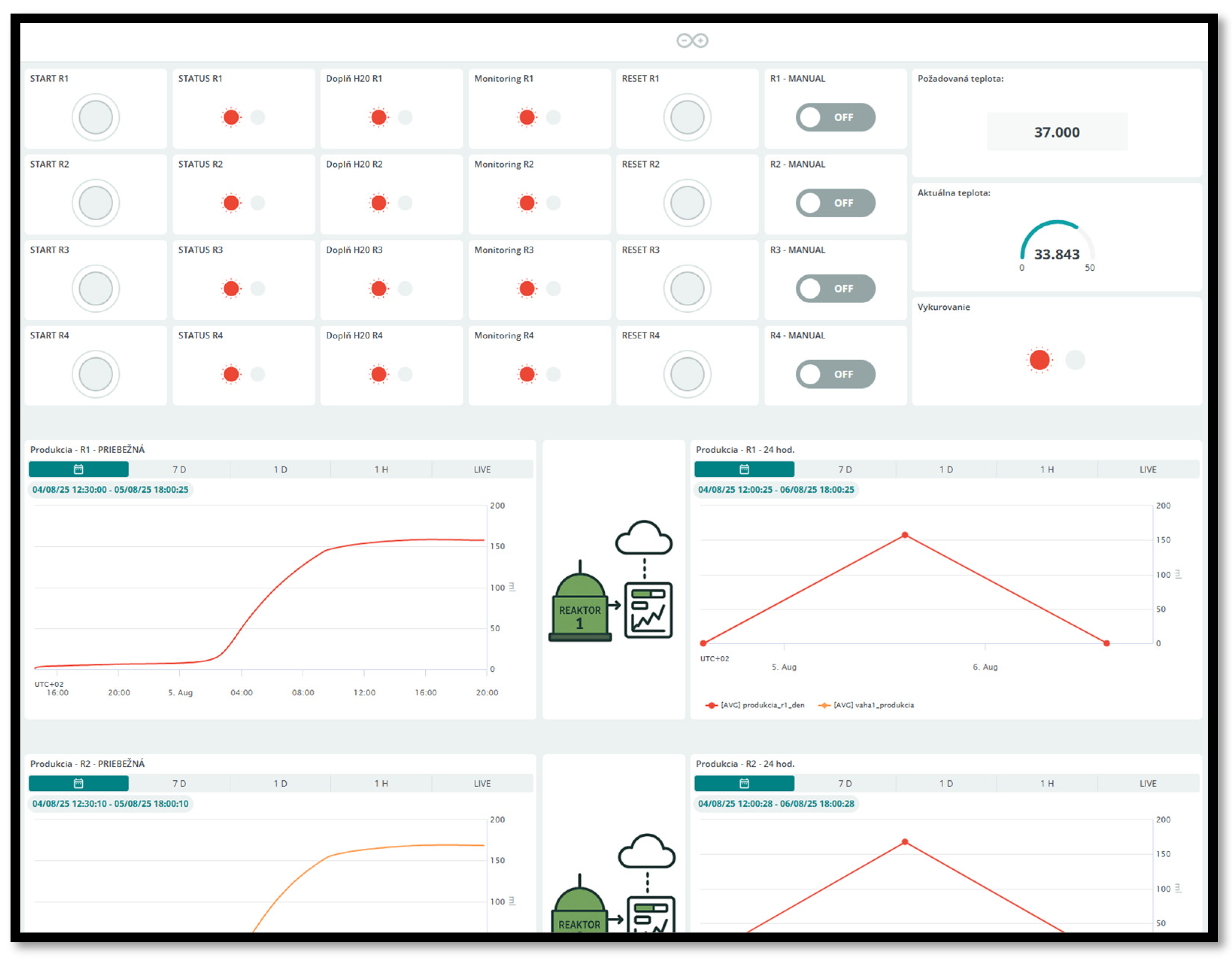

2.5. Control Strategy and Software Architecture

- Accumulation—the generated gas increases the hydrostatic pressure in the U-tube, and the system continuously integrates the volume;

- Venting to the atmosphere—brief opening of the 3/2 valve equalizes pressure conditions (fixed time window);

- Refilling—the peristaltic pump restores the distilled water level to the reference point (activated only after triple confirmation of low level from consecutive samples);

- Stabilization—a short time window to suppress transient effects after valve/pump actions.

2.6. Signal Processing and Measurement Uncertainties

2.7. Experimentálny Protokol

2.8. Data Acquisition and Monitored Variables

3. Results

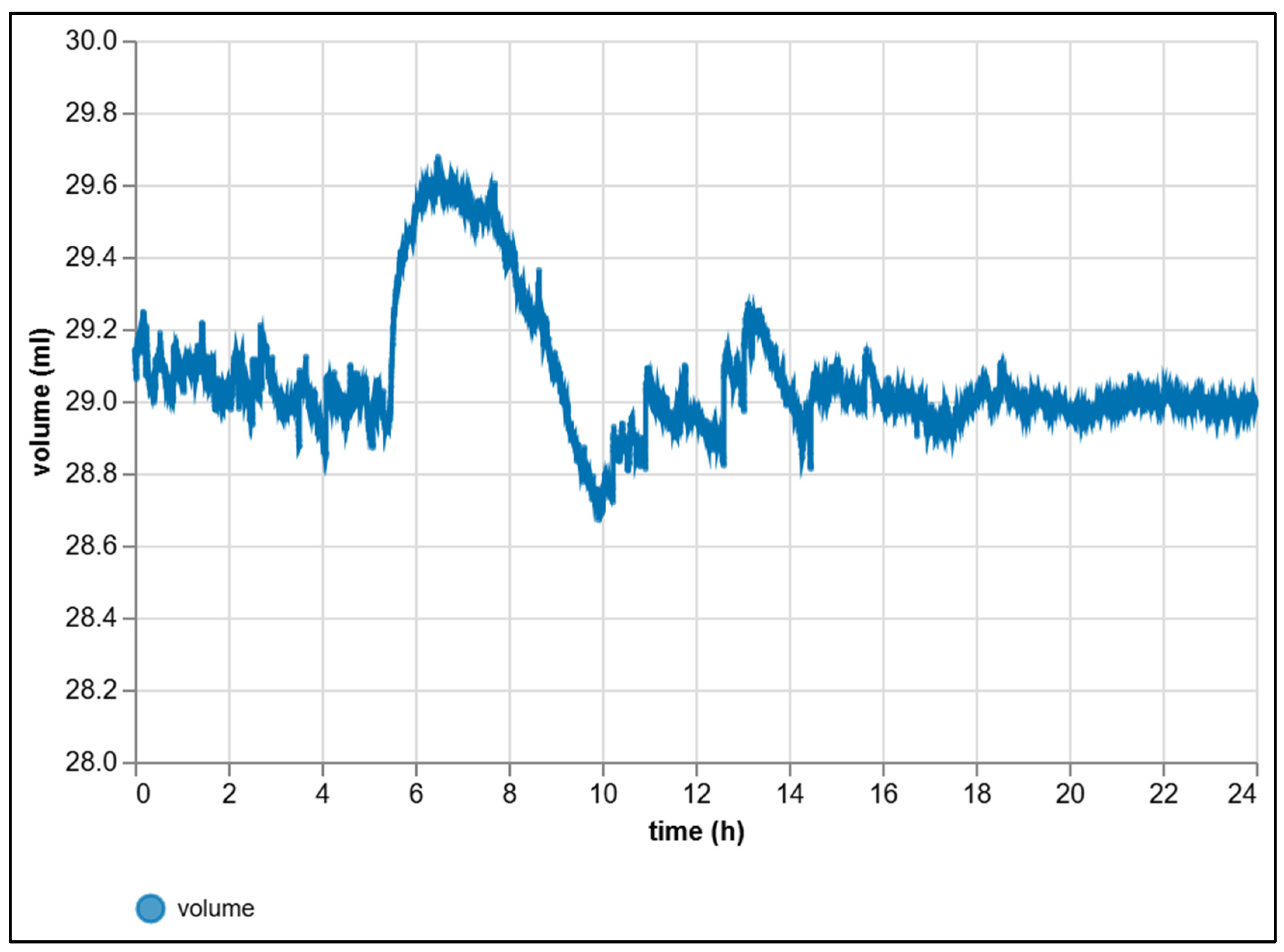

3.1. Verification of the Measuring Device

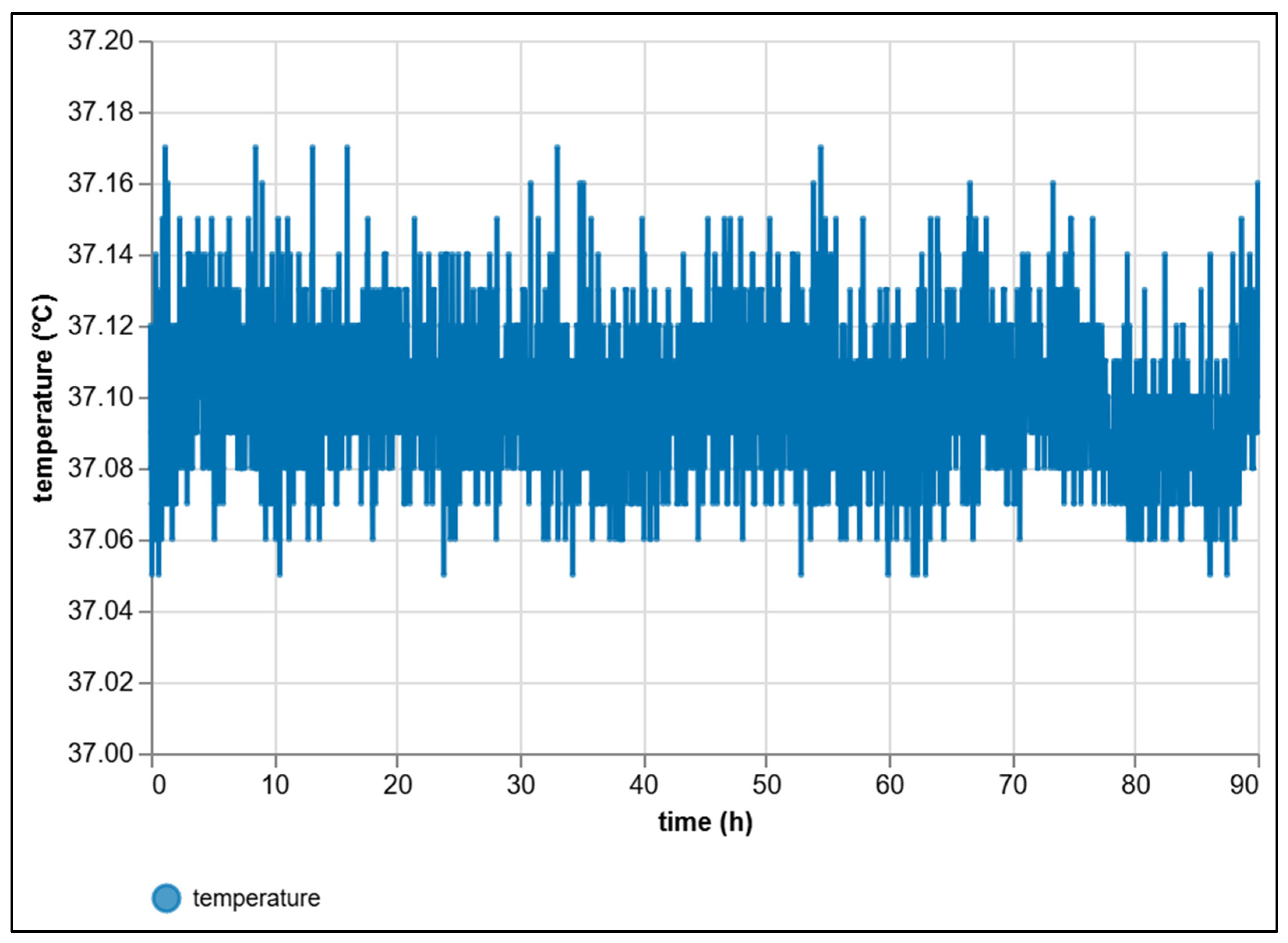

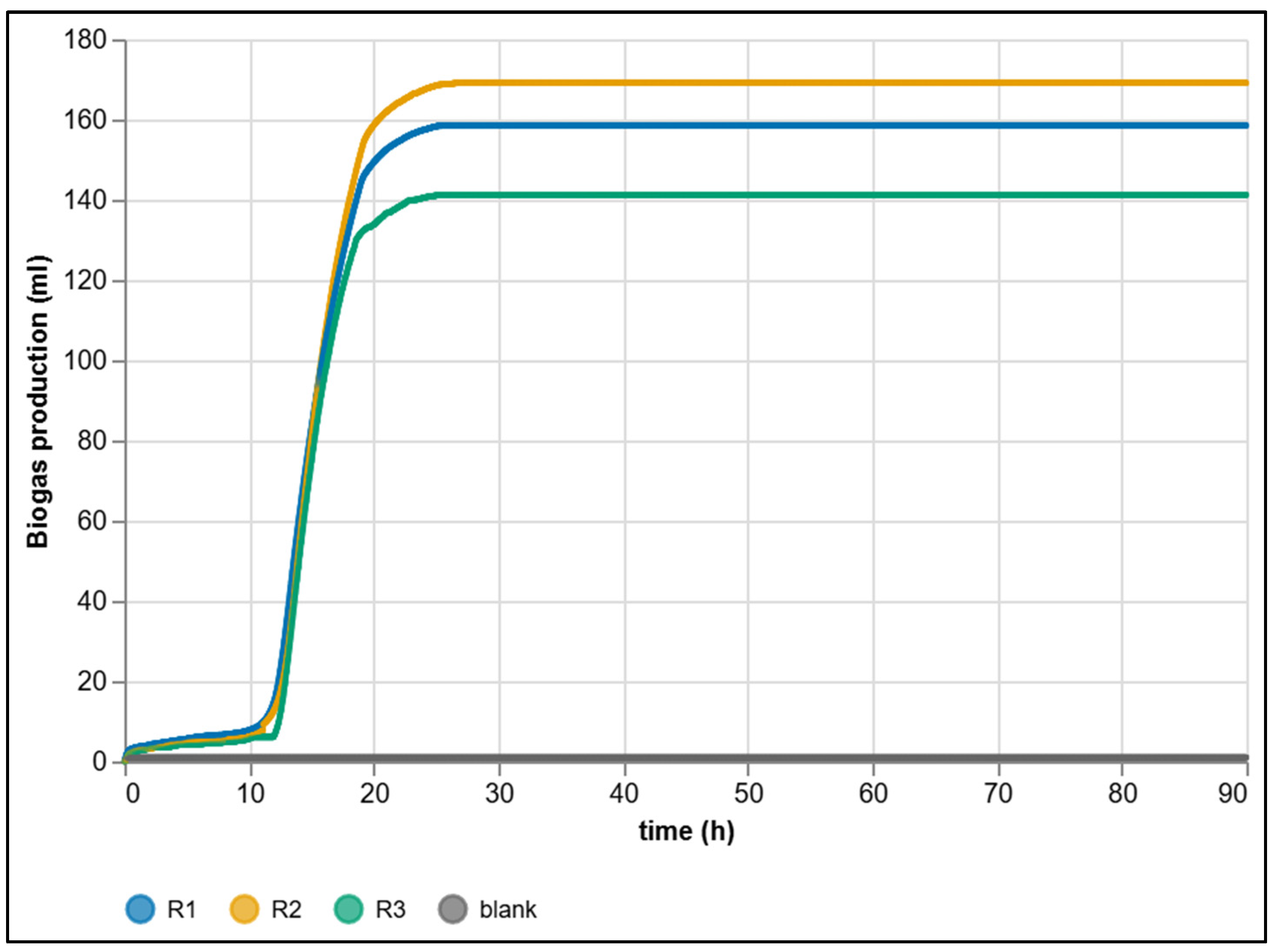

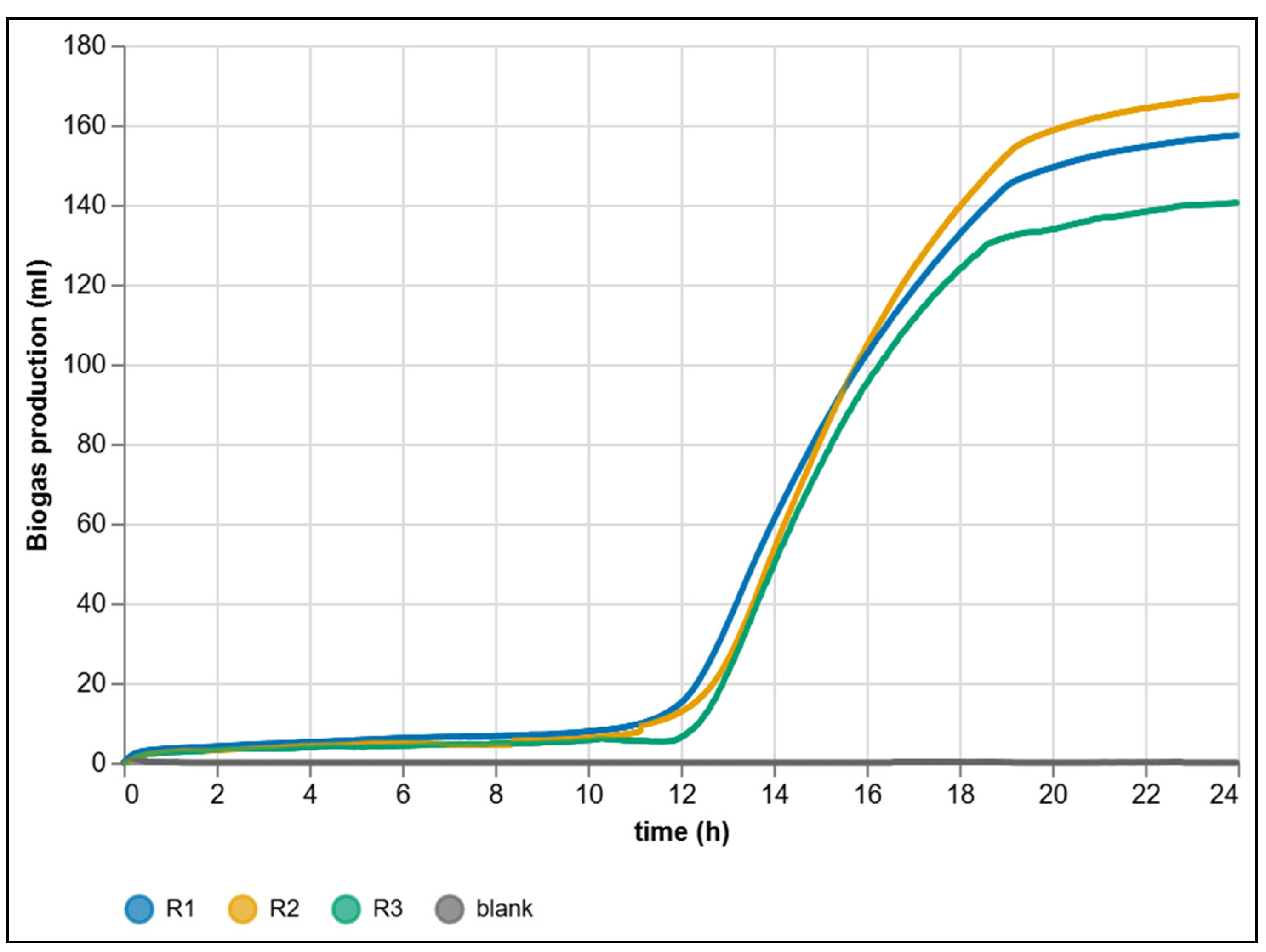

3.2. Dataset from Automated Measurement

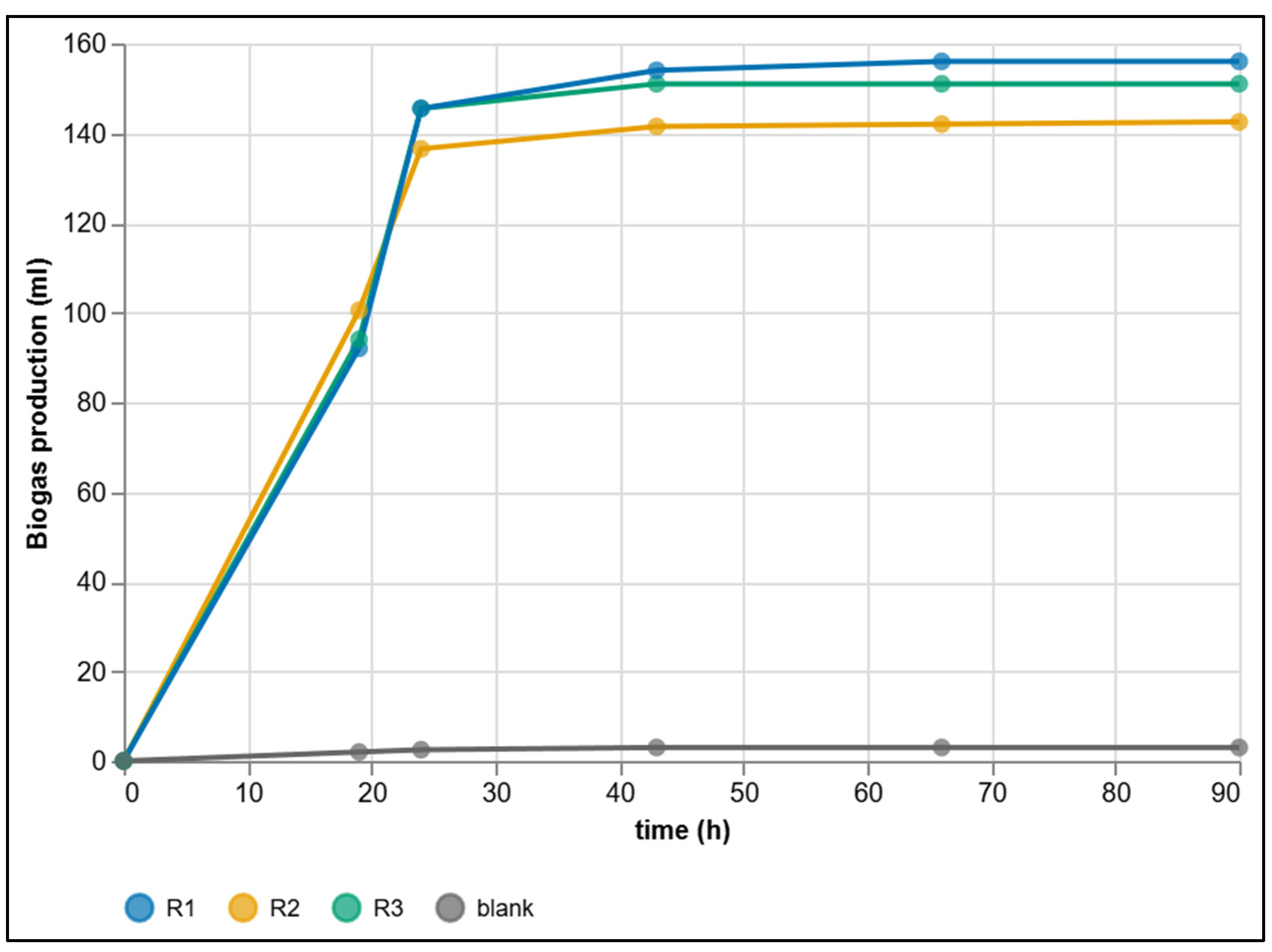

3.3. Dataset from Manual Methods

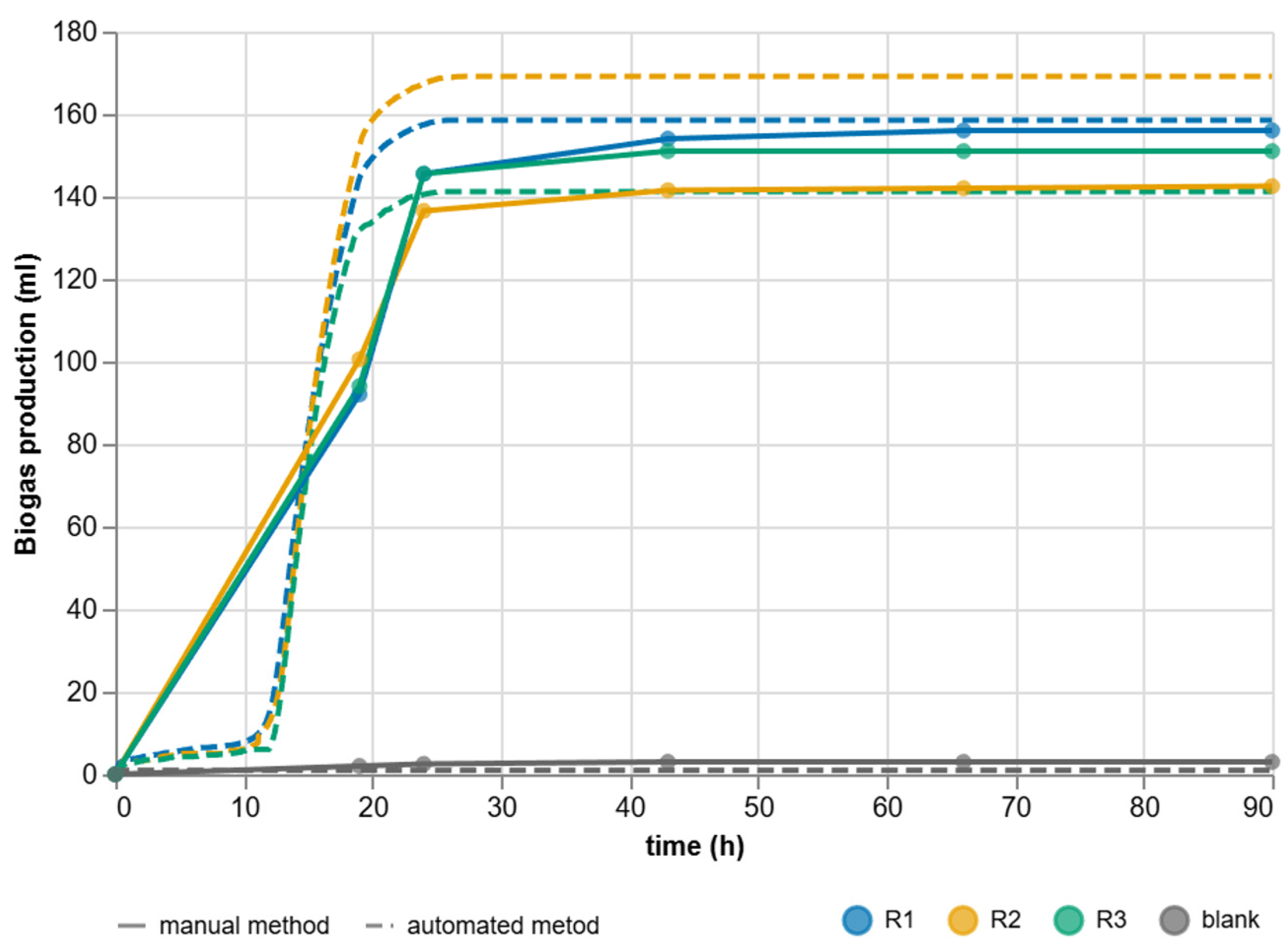

3.4. Comparison of Automated and Manual Approaches

3.5. Metrological Aspects of Automated Measurement

- Repeatability (item 1) was estimated from short-term variance under constant conditions. For a sensor full scale FS = 120 mbar and a specification of 0.1% FS, the absolute uncertainty is 0.12 mbar, which, after conversion using the sensitivity , corresponds to 0.062 mL. This component is absolute (it derives from measured data, accounting for the sensors’ technical documentation) and decreases relative to the measured volume. For example, for a single step this component accounts for 1.24%, whereas at a cumulative volume of 100 mL it drops to approximately 0.062%.

- Time granularity of the record (item 2) represents the discretization error of the integral. Acquisition at 1 Hz oversamples the dominant phenomena (time constants ), making its influence small. The upper bound of the trapezoidal-integration error is on the order of . The estimate of this component is 0.8%, with a shorter step and a guard window after switching reducing aliasing of transients.

- Integration of the initial dynamics (item 3) concerns the most sensitive segment of the measurement—the ramp-up from the lag phase. If the moment of ramp-up is uncertain by , it causes a volumetric deviation of approximately . With continuous recording and a short guard window, the uncertainty is small. A value of 0.5% is retained as residual risk, which includes delay and smoothing of the derivative.

- Evaluation method (item 4) includes temperature/pressure corrections, choice of integration, and rules for outliers. Differences among reasonable choices are typically below 1%, therefore 1.0% is estimated conservatively. The key is transparent, deterministic data processing (the same rules for all runs) [27].

- Physical conditions in the measuring section (item 5) are determined by room-temperature fluctuations (±1 °C). A temperature change of ±1 °C alters the density of water around 22 °C by only ≈0.03% per 1 K. More significant are secondary effects such as gas solubility and media expansion. With reasonable compensation (reference to , stable water interface), this component is kept below 0.5%. Also considered are atmospheric pressure, humidity, and gravitational acceleration. These quantities are directly metrologically traceable to calibrated instruments of the respective measurands, were measured, and were included in the balance table.

- Other influences (item 6) include joint tightness, microbubbles, wall wetting, and biofilm, which affect the effective cross-section . These influences are managed by protocols (leak test, cleaning, standard filling). Also included are other system-wide effects which, in further development of covariances, may be mutually independent sources of uncertainty and thus contribute to the resulting uncertainty. For this reason, it is important to perform more experimental measurements on the prototype of the automated platform for measuring biogas production and, in the future, to address covariances that can increase—but also significantly decrease—the resulting uncertainty. Everything depends on whether the uncertainty components act concordantly or discordantly on the two considered uncertainty estimates; the influence of the function tied to the output quantity is also important.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaldor, G. Biomethane, Energy from Circularity. Circular Economy for Food. 2024. Available online: https://circulareconomyforfood.eu/en/biomethane-energy-from-circularity/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- SIEA. Quantification of the Sustainable Regional Energy Potential of Biogas Plants; Slovakian Innovation and Energy Agency: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2023; Available online: https://www.siea.sk/wp-content/uploads/odborne_o_energii/Dokumenty/kvantifikacia-potencialu-bioplyn.stanic.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Drosg, B. Process Monitoring in Biogas Plants: Technical Brochure; IEA Bioenergy: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: https://www.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Technical-Brochure-process_montoring.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Cruz, I.A.; Andrade, L.R.; Bharagava, R.N.; Nadda, A.K.; Bilal, M.; Figueiredo, R.T.; Ferreira, L.F. An overview of process monitoring for anaerobic digestion. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 207, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitophyta, L.M.; Budiarti, G.I.; Nugroho, Y.E.; Fajariyanto, D. Biogas Production from Corn Stover by Solid-State Anaerobic Co-digestion of Food Waste. J. Tek. Kim. Lingkung. 2020, 4, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.H.; Triolo, J.M.; Cu, T.T.; Pedersen, L.; Sommer, S.G. Validation and Recommendation of Methods to Measure Biogas Production Potential of Animal Manure. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pérez-Vidal, A.; Bermeo Varón, L.A.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, L.M.; Bolaños-Muñoz, S.M.; Lemos-Valencia, Y.M.; Silva-Leal, J.A.; Torres-Lozada, P. Development of a Continuous Biogas Pressure Measurement Device with Applications in Batch Anaerobic Digestion Tests. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 36974–36984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, S.D.; Lettinga, G.; Astals, S. Systematic Error in Manometric Measurement of Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP). Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 284, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honeywell. ABP2 Series Board Mount Pressure Sensors Datasheet, Issue A. 2021. Available online: https://www.mouser.com/catalog/specsheets/Honeywell_ABP2%20Series%20Datasheet%20−%20Issue%20A.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- ArduinoModulesInfo. KY-013 Analog Temperature Sensor Module. Available online: https://arduinomodules.info/ky-013-analog-temperature-sensor-module/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Arduino. ABX00083 Product Reference Manual/Datasheet. 07/10/2025 (Modified). Available online: https://docs.arduino.cc/resources/datasheets/ABX00083-datasheet.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- SMC Corporation. VT307 Series 3-Port Solenoid Valve Datasheet. Available online: https://ca01.smcworld.com/catalog/en/directional/VT307-E/7-2-4-p1241-1250-VT307_en/data/7-2-4-p1241-1250-VT307_en.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- LaskaKit. Grothen G328 Peristaltic Pump 12V. Available online: https://www.laskakit.cz/grothen-g328-peristalticke-cerpadlo-12v/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Drotik Elektro. High-Torque Gear Motor DC 12V 14RPM S30K. Available online: https://www.drotik-elektro.sk/arduino-platforma/1506-motor-s-prevodovkou-a-vysokym-krutiacim-momentom-dc-12v-14rpm-s30k.html (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Techfun.sk. 8-Channel Relay Module 5V/12V. Available online: https://techfun.sk/produkt/8-kanalove-rele-5v-12v/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Techfun.sk. HX-M404 High-Power 8A Step-Down Converter with Voltmeter. Available online: https://techfun.sk/produkt/hx-m404-vykonny-step-down-menic-8a-s-voltmetrom/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- TRU Components. C-MZ45-FJ120-12V-ZK 12 V/DC, 120 W Heating Element (L × W × H: 87.5 × 60 × 42 mm). Available online: https://www.conrad.sk/sk/p/tru-components-c-mz45-fj120-12v-zk-vykurovaci-element-12-v-dc-120-w-d-x-s-x-v-87-5-x-60-x-42-mm-2887005.html (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Eclipsesera, s.r.o. PWM 15A 400 W MOSFET Module. 2021. Available online: https://www.drotik-elektro.sk/docs/produkty/1/1278/1502439140.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Techfun.sk. Switched-Mode Power Supply 12 V. Available online: https://techfun.sk/produkt/spinany-napajaci-zdroj-12v/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Ayars, J. PID Temperature Control Theory; Department of Physics, California State University: Chico, CA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://physics.csuchico.edu/ayars/427/handouts/ThermoPID.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Department of Physics, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice. Hydrostatic Pressure. Available online: https://physedu.science.upjs.sk/kvapaliny/tlakkvap.htm (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Košťálková, Z. Cylinder Volume Formula: Calculate It Easily! E-zone.sk. 10 Januára 2025. Available online: https://e-zone.sk/objem-valce-vzorec-spocitajte-si-ho-jednoduse/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Leito, I. 4.2. Calculating the combined standard uncertainty. In Estimation of Measurement Uncertainty in Chemical Analysis; University of Tartu: Tartu, Estonia, 2013; Available online: https://sisu.ut.ee/measurement/42-combining-uncertainty-components-combined-standard-uncertainty/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Elektrolab. Pressure Unit Conversion. Elektrolab. 18 Augusta 2023. Available online: https://www.elektrolab.eu/blog/prevod-jednotiek-tlaku (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- VDI 4630; Vergärung Organischer Stoffe: Substratcharakterisierung, Probenahme, Stoffdatenerhebung, Gärversuche. Verein Deutscher Ingenieure: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2006. Available online: https://www.dinmedia.de/de/technische-regel/vdi-4630/86939477 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Chudy, V.; Palencar, R.; Kurekova, E.; Halaj, M. Measurement of Technical Quantities, 1st ed.; Slovak University of Technology: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grosinger, P.; Rybář, J.; Dunaj, Š.; Ďuriš, S.; Hučko, B. A New Payload Swing Angle Sensing Device and Its Accuracy. Sensors 2021, 21, 6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holliger, C.; Alves, M.; Andrade, D.; Angelidaki, I.; Astals, S.; Baier, U.; Bougrier, C.; Buffière, P.; Carballa, M.; De Wilde, V.; et al. Towards a Standardization of Biomethane Potential Tests. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 2515–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holliger, C.; Astals, S.; Fruteau de Laclos, H.; Hafner, S.D.; Koch, K.; Weinrich, S. Towards a Standardization of Biomethane Potential Tests: A Commentary. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalamaras, S.D.; Tsitsimpikou, M.-A.; Tzenos, C.A.; Lithourgidis, A.A.; Pitsikoglou, D.S.; Kotsopoulos, T.A. A Low-Cost IoT System Based on the ESP32 Microcontroller for Efficient Monitoring of a Pilot Anaerobic Biogas Reactor. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; An, D.; Cao, Y.; Tian, Y.; He, J. Modeling the Methane Production Kinetics of Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Agricultural Wastes Using Sigmoidal Functions. Energies 2021, 14, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momodu, A.S.; Adepoju, T.D. System Dynamics Kinetic Model for Predicting Biogas Production in Anaerobic Condition: Preliminary Assessment. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galal, O.H.; Abdel-Daiem, M.M.; Alharbi, H.S.; Said, N. Mathematical Modeling and Machine Learning Approaches for Biogas Production from Anaerobic Digestion: A Review. BioResources 2025, 20, 11237–11266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihi, M.; Ouhammou, B.; Aggour, M.; Daouchi, B.; Naaim, S.; El Mers, E.M.; Kousksou, T. Modeling and Forecasting Biogas Production from Anaerobic Digestion Process for Sustainable Resource Energy Recovery. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Chen, R.; Guan, S.; Li, W.-T.; Yuen, C. BuildingGym: An open-source toolbox for AI-based building energy management using reinforcement learning. Build. Simul. 2025, 18, 1909–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; He, P.; Peng, W.; Lü, F.; Du, R.; Zhang, H. Exploring available input variables for machine learning models to predict biogas production in industrial-scale biogas plants treating food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPC Instruments AB. AMPTS III—Automatic Methane Potential Test System. Available online: https://bpcinstruments.com/bpc_products/automatic-methane-potential-test-system/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- VELP Scientifica. RESPIROMETRIC Sensor System 6 Maxi—BMP. Available online: https://www.velp.com/en-ww/respirometric-sensor-system-6-maxi-bmp.aspx (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Anaero Technology Ltd. Anaero Technology. Available online: https://www.anaerotech.com/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Amodeo, C.; Hafner, S.D.; Teixeira Franco, R.; Benbelkacem, H.; Moretti, P.; Bayard, R.; Buffière, P. How Different Are Manometric, Gravimetric, and Automated Volumetric BMP Results? Water 2020, 12, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Asri, O.; Afilal, M.E. Comparison of the Experimental and Theoretical Production of Biogas by Monosaccharides, Disaccharides, and Amino Acids. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 1957–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Manual BMP Methods | Automated BMP Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement mode | discontinuous measurements (manual readings) | continuous or semi-continuous data acquisition |

| Time resolution | 4–24 h (depending on operator availability) | seconds to minutes (adjustable) |

| Data acquisition | subjective, operator-dependent | objective, automated |

| Measurement accuracy | ±5–10%; dependent on reading frequency | stable; defined by sensor specifications and workflow |

| Systematic errors | negative bias, gas loss during venting, pressure drift | minimized through controlled, repeatable measurement cycles |

| Sensitivity to temperature fluctuations | high (gas-phase expansion/contraction) | lower (faster and more stable response) |

| Detection of transient events | practically impossible | captured in real time |

| Operator workload | high—manual manipulation and monitoring | low—automated operation |

| Reproducibility | low inter-lab reproducibility | high, due to defined algorithmic control |

| Inter-lab variability | differences may exceed 100% for identical substrates | reduced when using standardized hardware and protocol |

| Equipment cost | low–moderate (manual setups) | low (DIY/low-cost designs) or high (commercial MFC systems) |

| Modularity/openness | limited | high (especially with open-source platforms) |

| Metric | VR1 | VR2 | VR3 | Mean ± SD | 95% CI (Final Only) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final cumulative production (mL) | 158.494 | 169.122 | 141.185 | 156.27 ± 11.65 | 127.4–185.2 |

| Daily production 0–24 h (mL/day) | 157.382 | 167.382 | 140.477 | 155.08 ± 13.67 | — |

| Daily production 24–48 h (mL/day) | 1.112 | 1.740 | 0.708 | 1.19 ± 0.52 | — |

| Daily production 48–72 h (mL/day) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 ± 0 | — |

| Daily production 72–90 h (mL/day) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 ± 0 | — |

| Measured Reactor Volume | Manual Method After 90 h (mL) | Automated Method After 90 h (mL) |

|---|---|---|

| VR1 | 153.0 | 157.53 |

| VR2 | 148.0 | 168.16 |

| VR3 | 139.5 | 140.23 |

| Mean (VR1–VR3) | 146.83 | 155.31 |

| Source of Uncertainty | Symbol of Uncertainty | Uncertainty Value | Absolute Uncertainty (mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability | uA | 0.1% FS of the sensor | --- | |

| Time granularity of the measurement process * | uB1 | 0.8% | × | exponential |

| Integration of initial dynamics * | uB2 | 0.5% | × | exponential |

| Evaluation method | uB3 | 1.0% | × | normal |

| Physical conditions ** | uB4 | 0.5% | × | normal |

| Other influences | uB5 | 0.5% | × | normal |

| uc | ||||

| U (k = 2) | ||||

| Parameter | AMPTS III (Flow Cell) | VELP Maxi (Manometric) | AnaeroTech BMP/Nautilus (Volumetric) | Pérez-Vidal 2025 [7] (IoT Manometric) | Proposed Hydrostatic Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement mode | Optical pulse-based flow cells | Headspace pressure → volume | Water-displacement burette | Continuous headspace pressure sensing | Differential pressure → hydrostatic column |

| Resolution | ~0.05–0.1 mL | 0.1–0.5 mL | 0.5–2 mL | 1 mbar sensor resolution (≈0.2–1 mL depending on headspace) | ~0.06 mL |

| Short-term variability (σ) | 0.05–0.10 mL | 0.10–0.50 mL | 0.50–2.00 mL | ~1 mbar (noise) | 0.06 mL |

| Expanded uncertainty (≈100 mL) | 2–3% | 5–10% | 5–20% | 7.6 mbar | ~3.1% |

| Long-term drift | Very low | High (temp + solubility) | Operator-driven/irregular | High drift due to CO2 dissolution and temperature | <0.15%/24 h |

| Sensitivity to CO2 solubility | Low | Very high | Medium | Very high (headspace thermodynamics) | Eliminated (open hydrostatic loop) |

| Disturbance/gas loss | None | Moderate | Moderate | 50.7 ± 12.9 mbar loss per reading | None |

| Temporal resolution | ~1–2 Hz | 10–60 s | Manual | 1 × per hour | 11 Hz internal/1 Hz logging |

| Automation | Full (industrial) | Partial | Low | Medium | Full (refill, venting, cloud) |

| Scalability | 6–18 reactors | 6 | 6–15 | 4 | 4 + modular |

| Typical cost | €20 k–35 k | €10 k–15 k | €4 k–8 k | €150–300 | ~€2 k |

| Primary limitation | Proprietary/high cost | Drift + solubility error | Manual variability | Strong dependence on headspace physics | No gas composition sensor (optional) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Habara, M.; Molitoris, J.; Jankovičová, B.; Rybář, J.; Vachálek, J. Hydrostatic Water Displacement Sensing for Continuous Biogas Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 7297. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237297

Habara M, Molitoris J, Jankovičová B, Rybář J, Vachálek J. Hydrostatic Water Displacement Sensing for Continuous Biogas Monitoring. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7297. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237297

Chicago/Turabian StyleHabara, Marek, Jozef Molitoris, Barbora Jankovičová, Jan Rybář, and Ján Vachálek. 2025. "Hydrostatic Water Displacement Sensing for Continuous Biogas Monitoring" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7297. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237297

APA StyleHabara, M., Molitoris, J., Jankovičová, B., Rybář, J., & Vachálek, J. (2025). Hydrostatic Water Displacement Sensing for Continuous Biogas Monitoring. Sensors, 25(23), 7297. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237297