Wearable Multispectral Sensor for Newborn Jaundice Monitoring

Abstract

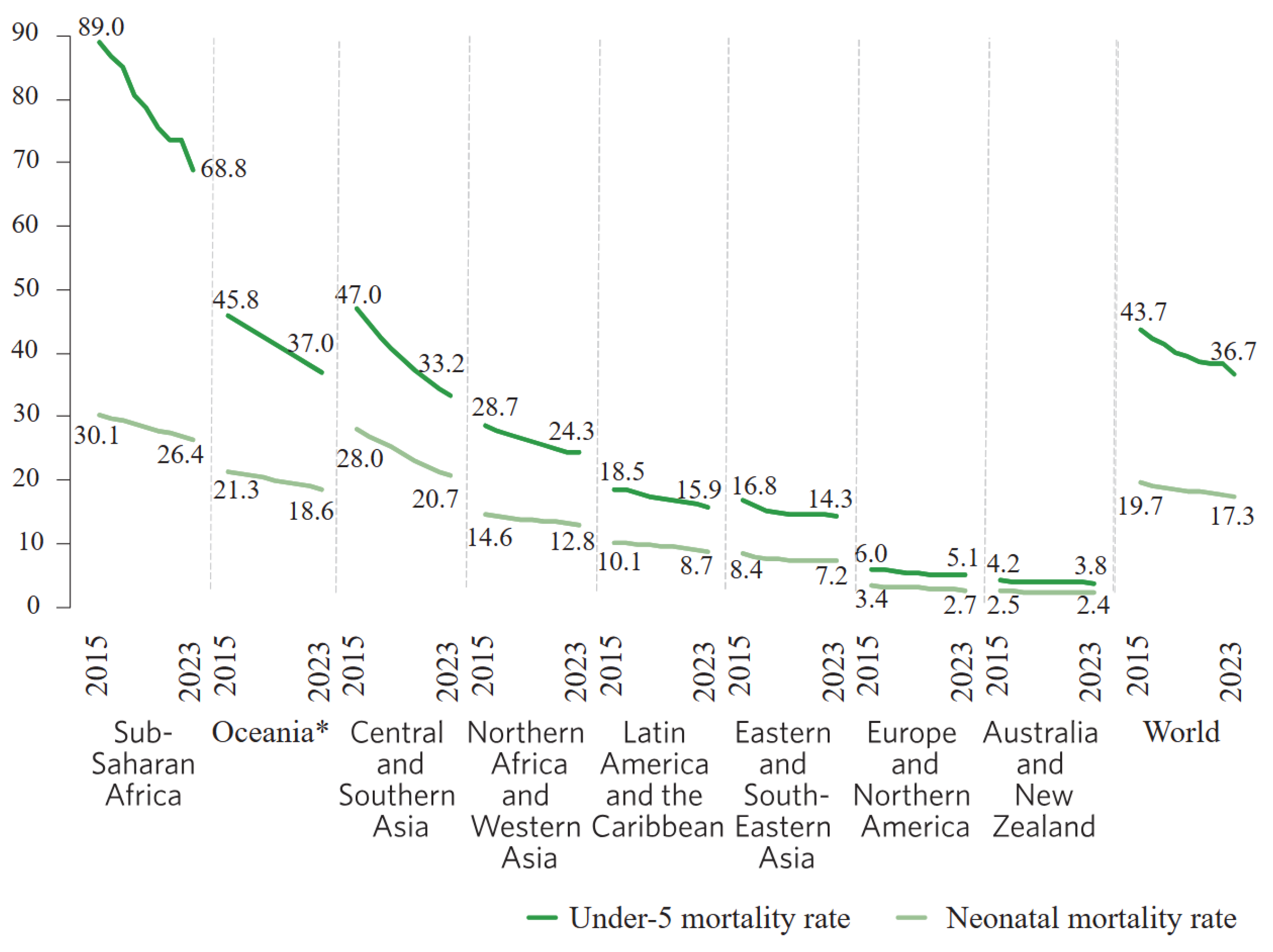

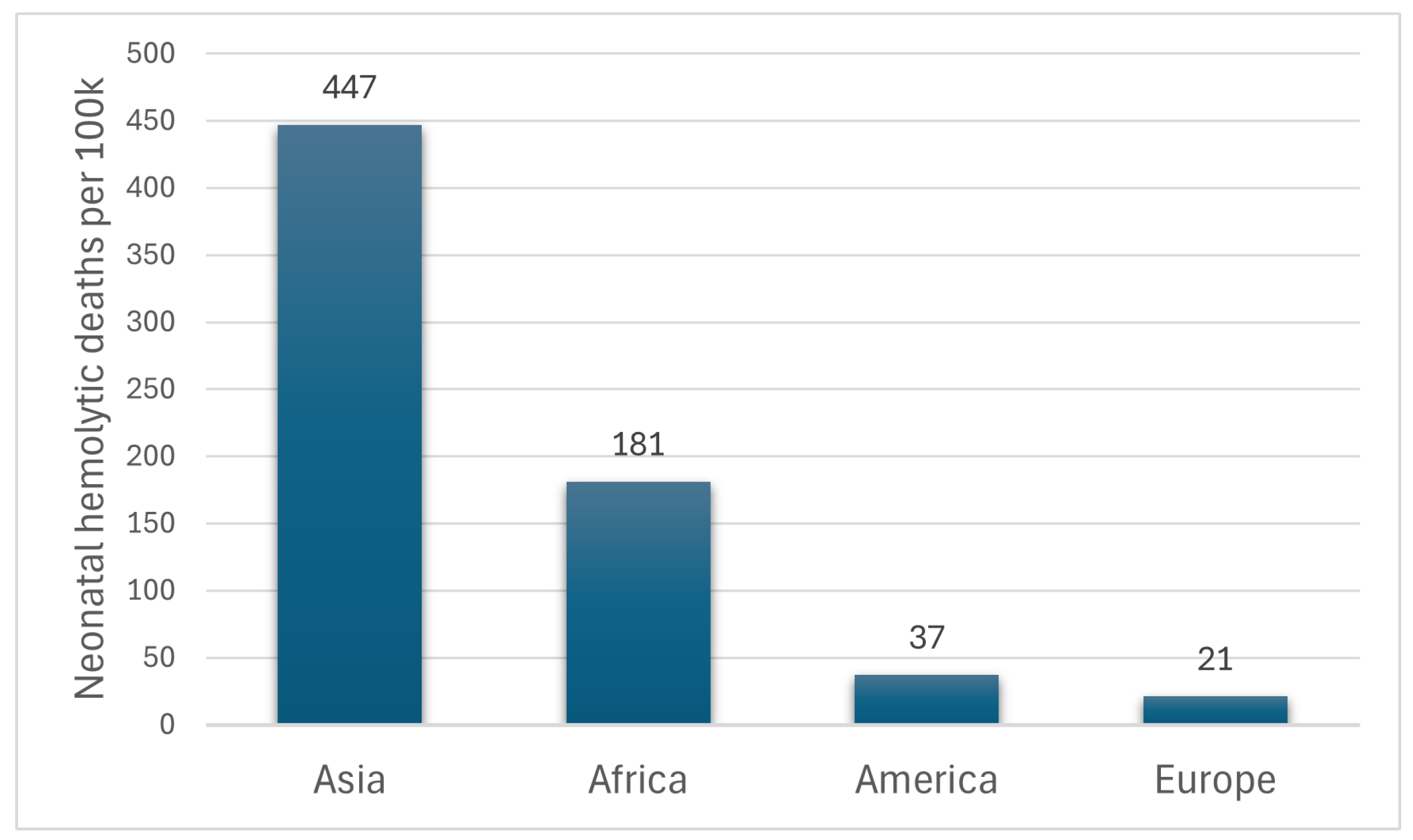

1. Introduction

Jaundice Management

2. Materials and Methods

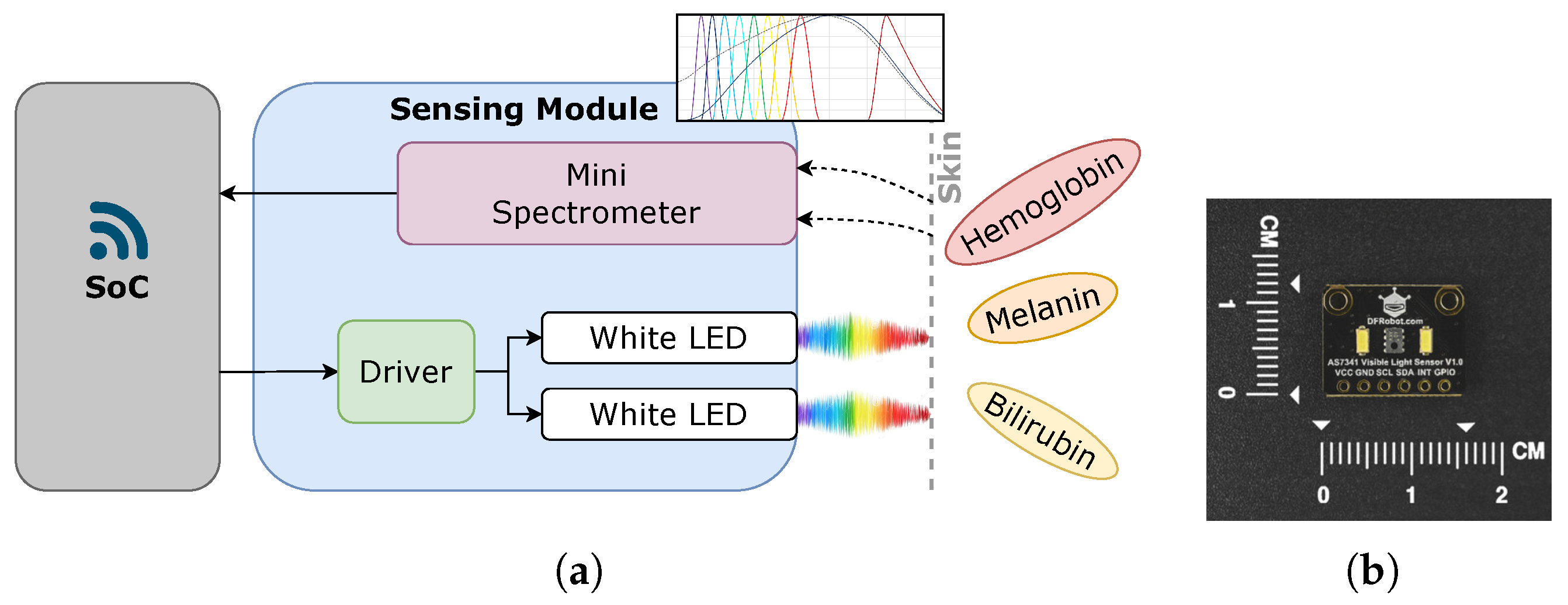

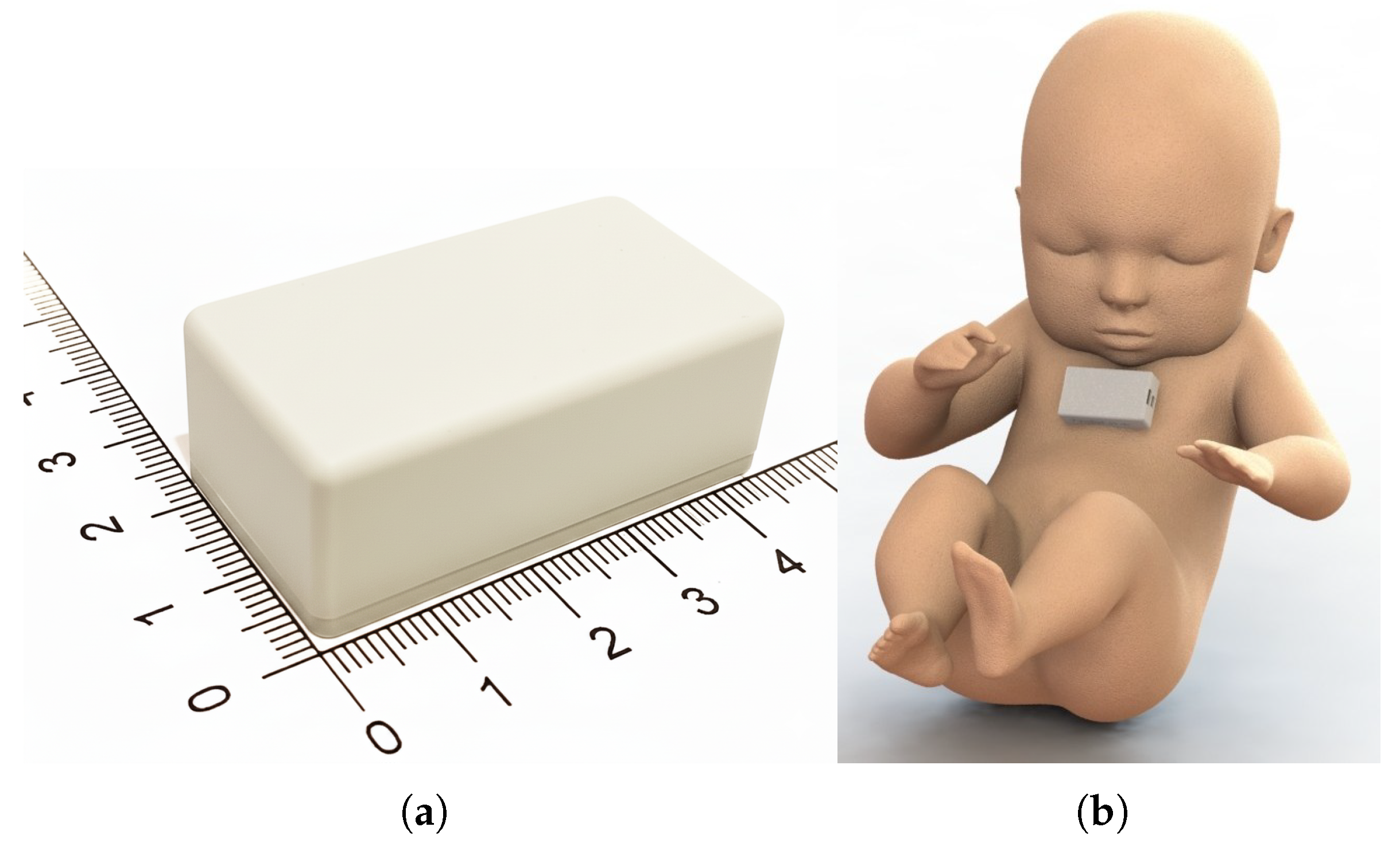

2.1. The Integrated Solution

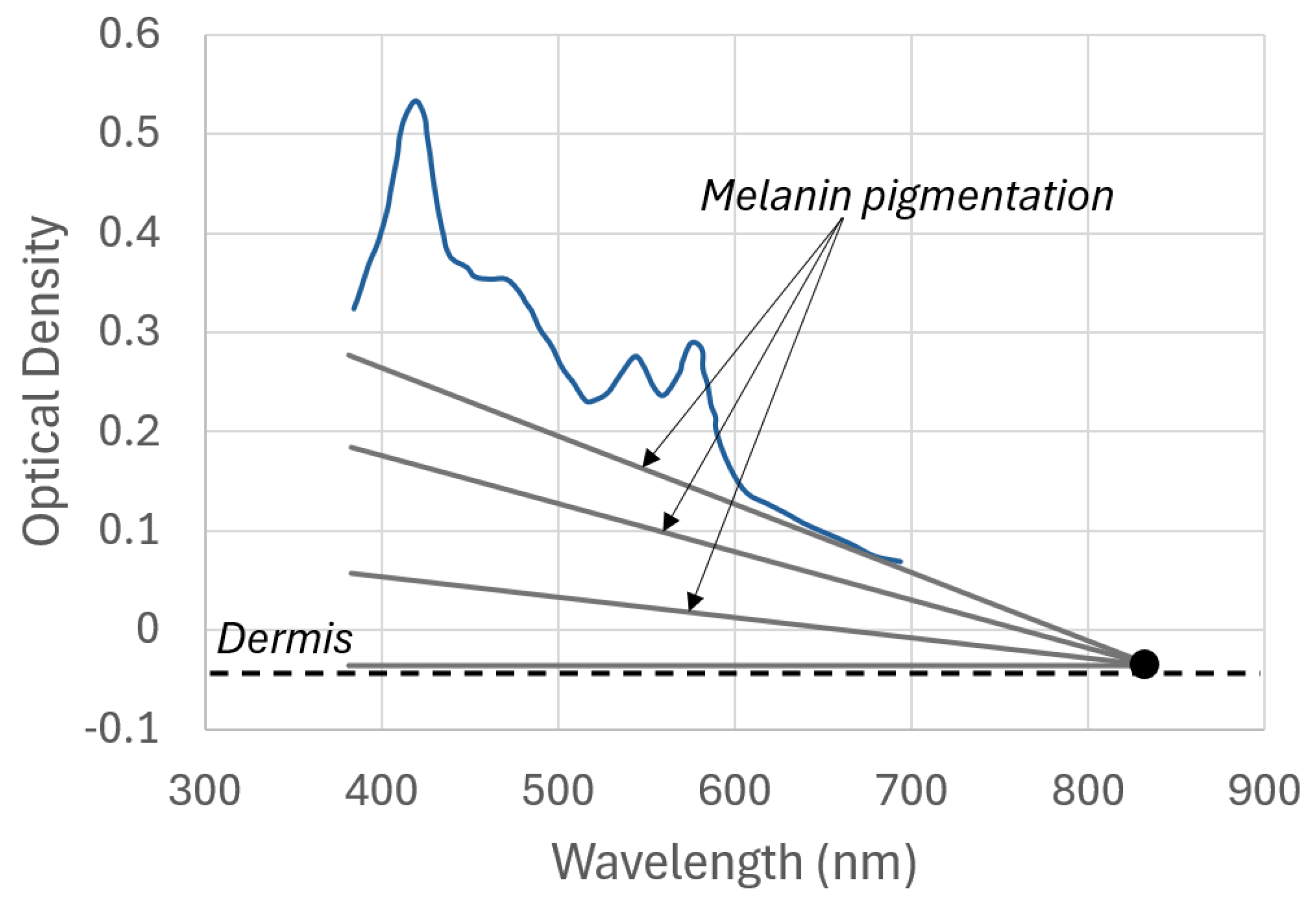

2.2. Light and Skin Relationship

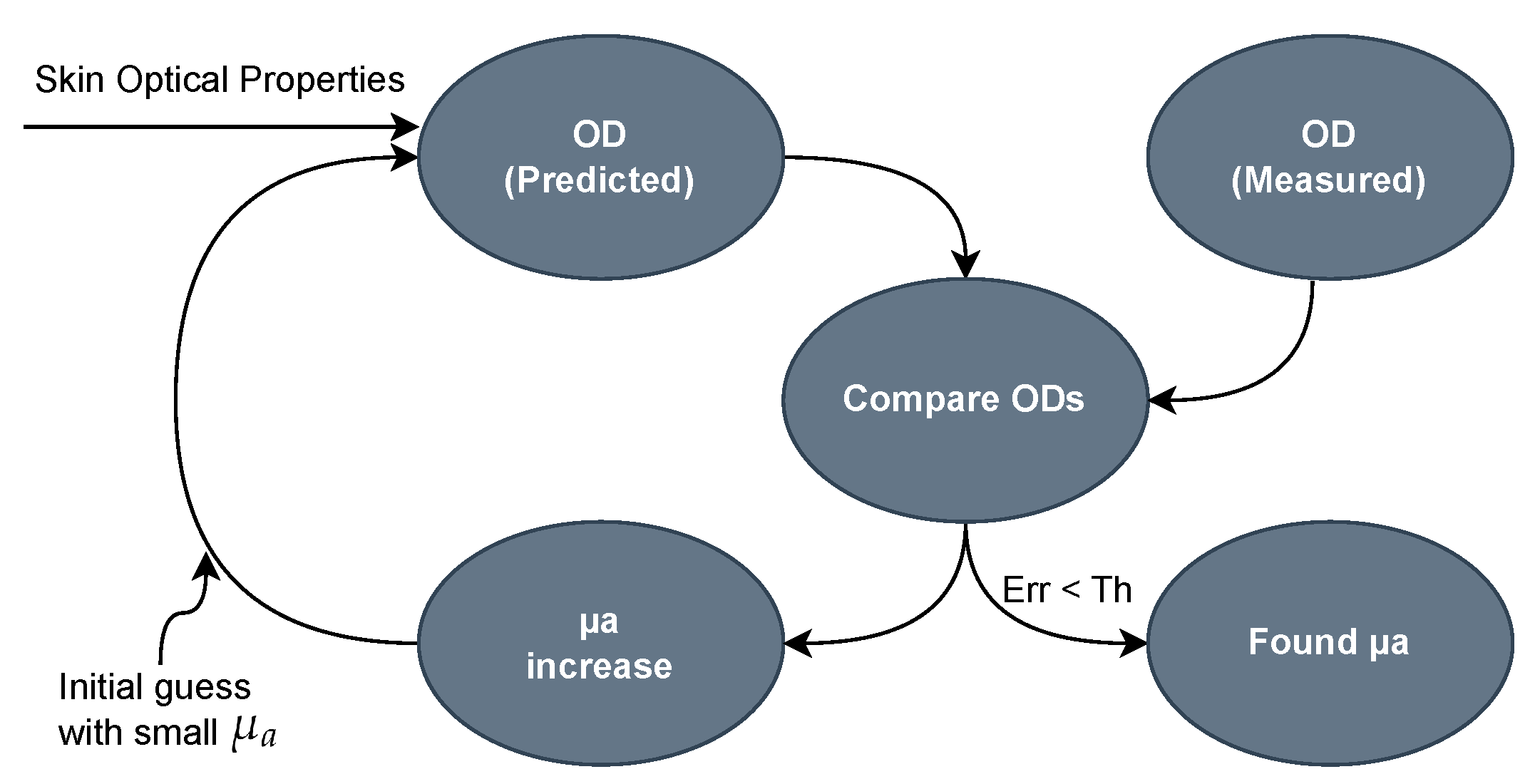

2.3. Bilirubin Calculation Algorithm

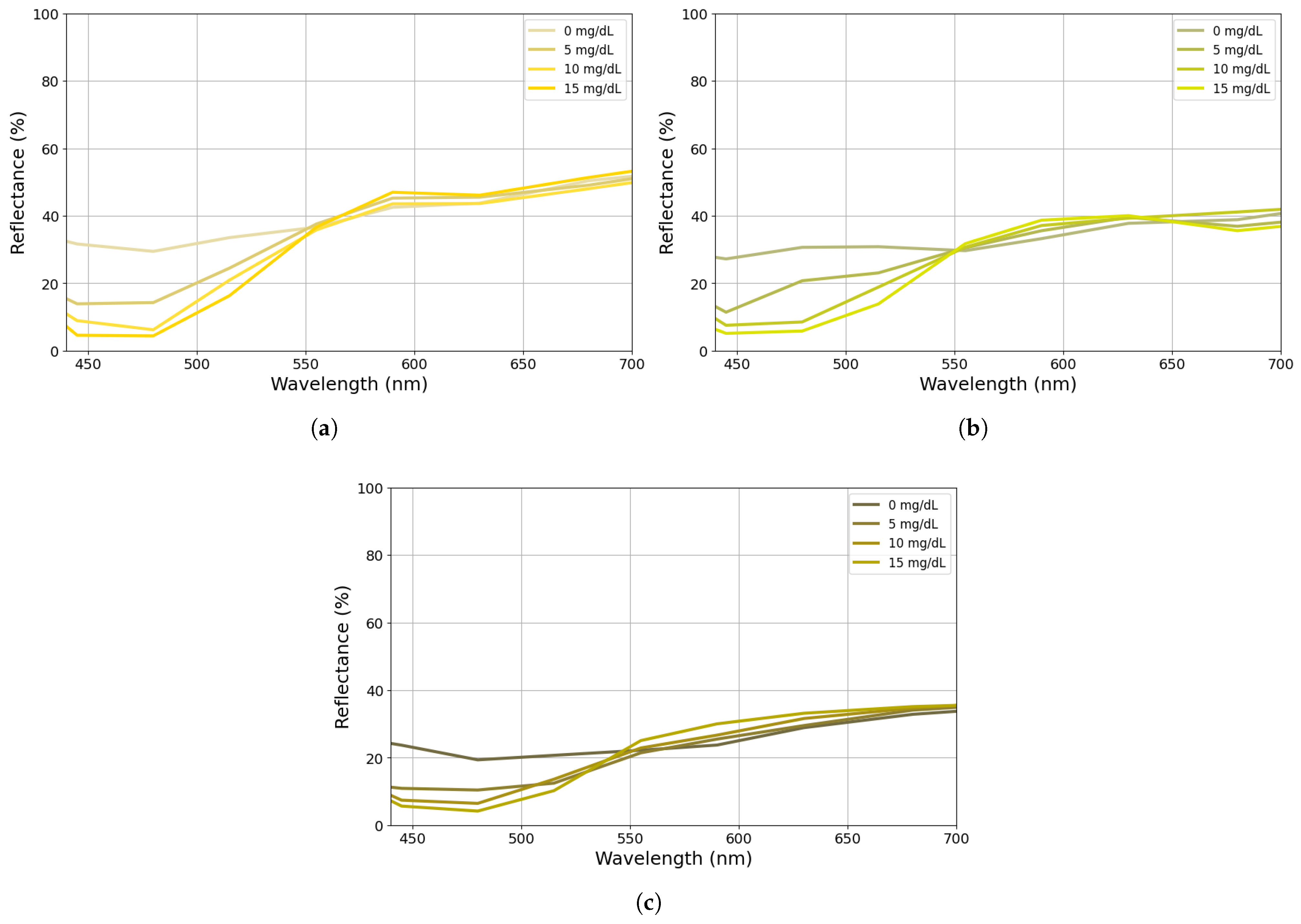

2.4. Calibration Procedure

- The spectra were extracted for each phantom and evaluated with respect to their melanin content;

- The melanin effect was removed from the spectra;

- What remained was the influence of blood, bilirubin, and skin in the blue range (460 nm), as presented in Equation (19);

- Finally, the values of and G were fine-tuned to achieve the best match for the predetermined bilirubin concentration levels of the phantoms.

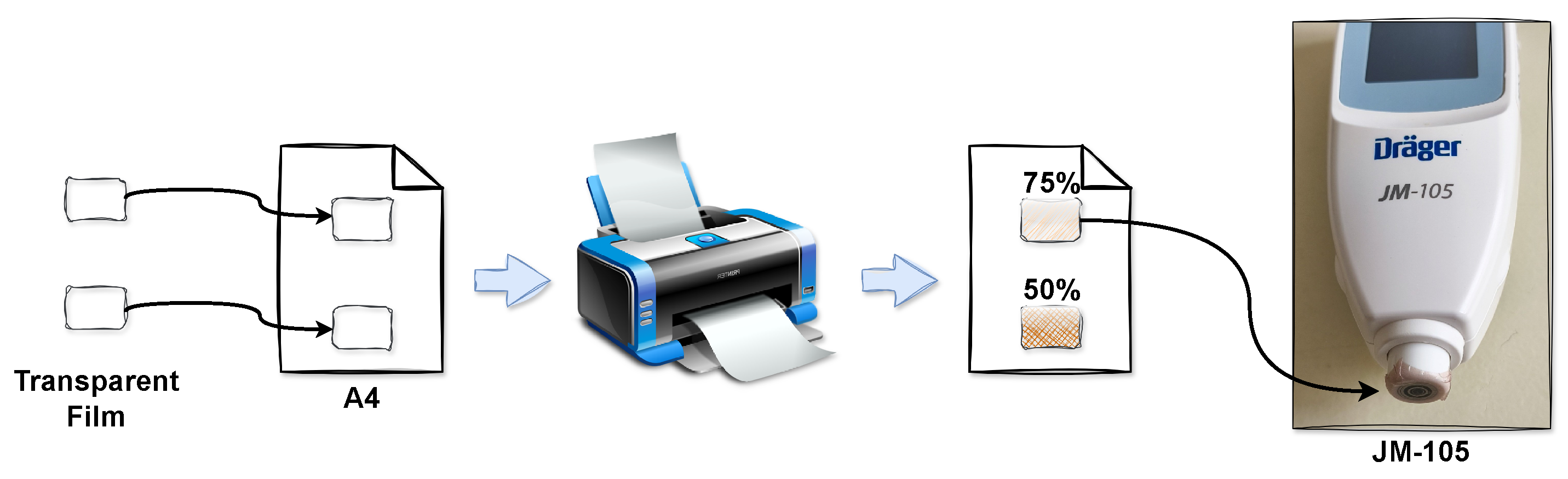

2.5. Comparison with Commercial Bilirubinometer

3. Results and Discussion

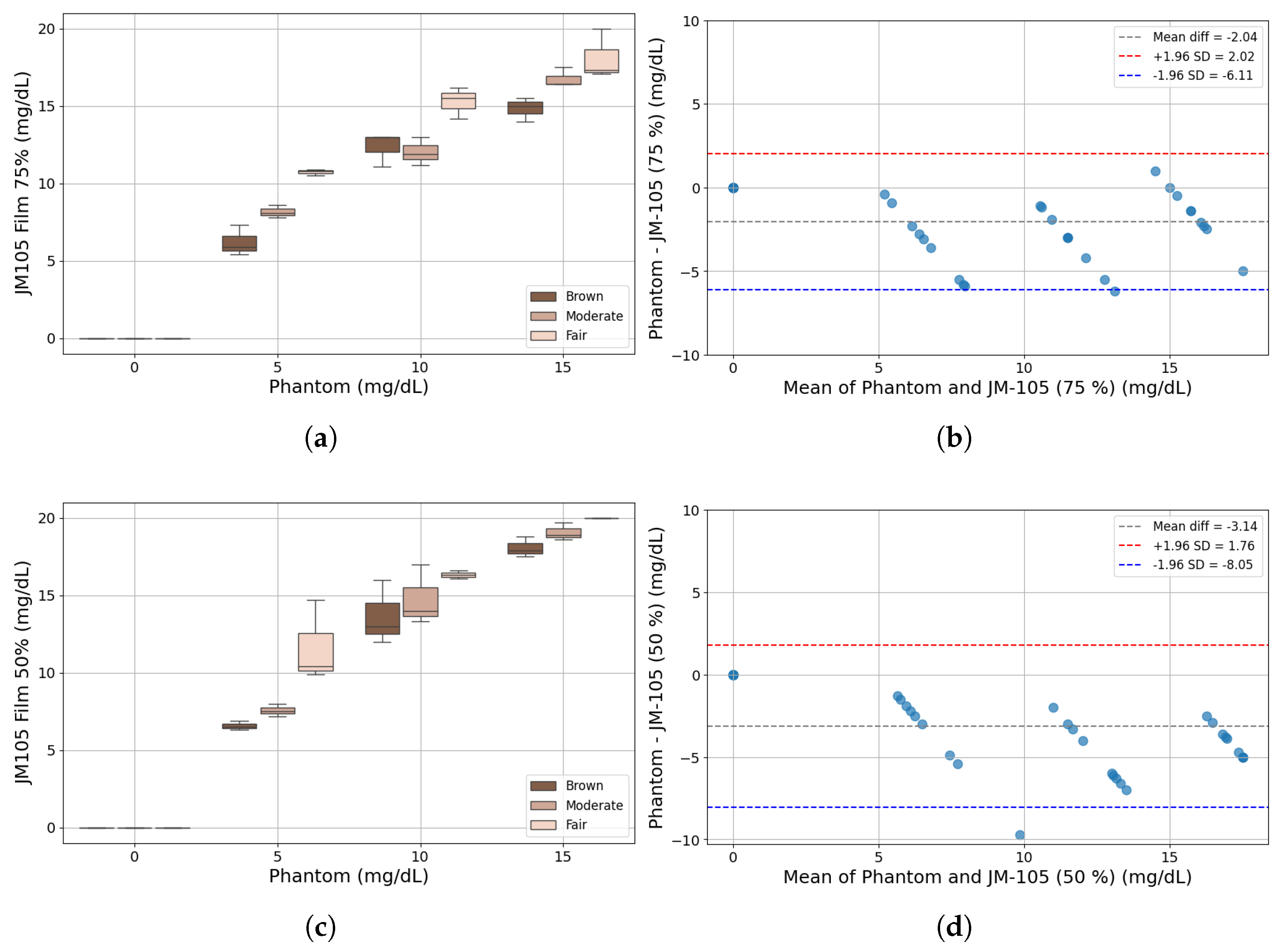

3.1. Bilirubinometer: JM-105

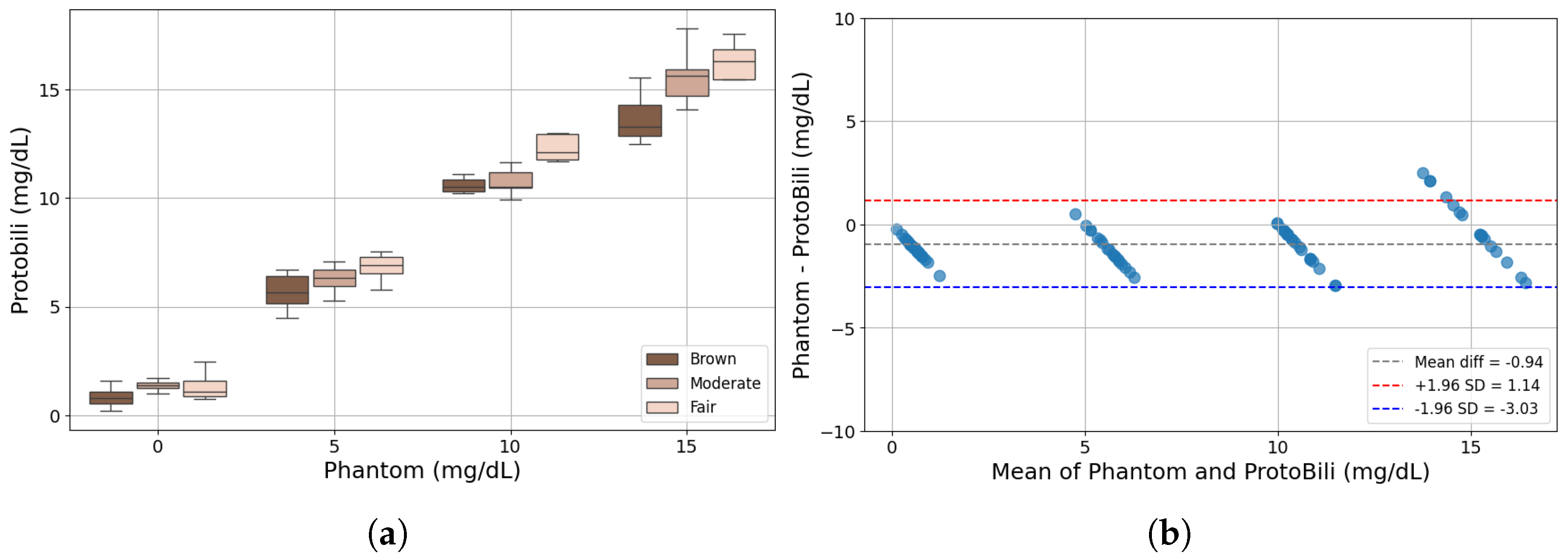

3.2. Bilirubinometer: ProtoBili

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Ensure Healthy Lives and Promote Well-Being for All at All Ages. 2025. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/Goal-03/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study (2021)-Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Bhutani, V.K.; Zipursky, A.; Blencowe, H.; Khanna, R.; Sgro, M.; Ebbesen, F.; Bell, J.; Mori, R.; Slusher, T.M.; Fahmy, N.; et al. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and Rhesus disease of the newborn: Incidence and impairment estimates for 2010 at regional and global levels. Ped. Res. 2013, 74, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diala, U.M.; Usman, F.; Appiah, D.; Hassan, L.; Ogundele, T.; Abdullahi, F.; Satrom, K.M.; Bakker, C.J.; Lee, B.W.; Slusher, T.M. Global Prevalence of Severe Neonatal Jaundice among Hospital Admissions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.; Britten, N.; Culpepper, L.; Gass, D.A.; Grol, R.; Mant, D.; Silagy, C. Oxford Text-Book of Primary Medical Care, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 758–761. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization-Effective Perinatal Care (EPC): Neonatology. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/108599/WHO-EURO-2010-7105-46871-68344-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Slusher, T.M.; Zipursky, A.; Bhutani, N.K.; Vinod, K. A Global Need for Affordable Neonatal Jaundice Technologies. Semin. Perinatol. 2011, 35, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaundice in Newborn Babies Under 28 Days-National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg98 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Ercan, Ş.; Özgün, G. The accuracy of transcutaneous bilirubinometer measurements to identify the hyperbilirubinemia in outpatient newborn population. Clin. Biochem. 2018, 55, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jnah, A.; Newberry, D.M.; Eisenbeisz, E. Comparison of Transcutaneous and Serum Bilirubin Measurements in Neonates 30 to 34 Weeks Gestation Before, During, and After Phototherapy. Adv. Neonatal Care 2018, 18, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Long, Z.; Yang, G.; Xing, L. Self-Powered Wearable Biosensor in a Baby Diaper for Monitoring Neonatal Jaundice through a Hydrovoltaic-Biosensing Coupling Effect of ZnO Nanoarray. Biosensors 2022, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam-Vervloet, A.J.; Morsink, C.F.; Krommendijk, M.E.; Nijholt, I.M.; van Straaten, H.L.M.; Poot, L.; Bosschaart, N. Skin color influences transcutaneous bilirubin measurements: A systematic in vitro evaluation. Ped. Res. 2024, 5, 1706–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, W.D.; Jackson, G.L.; Engle, N.G. Transcutaneous bilirubinometry. Semin. Perinatol. 2014, 38, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randeberg, L.L.; Roll, E.B.; Nilsen, L.T.N.; Christensen, T. In vivo spectroscopy of jaundiced newborn skin reveals more than a bilirubin index. Acta Paediatr. 2005, 94, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S.; Bührer, C.; Schmalisch, G.; Metze, B.; Berns, M. Rate of rise of total serum bilirubin in very low birth weight preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 87, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, P.; Chavda, H.; Doshi, V. Transcutaneous bilirubin nomogram for healthy term and late preterm neonates in first 96 h of life. Indian Pediatr. 2017, 54, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, V.K.; Chavda, H.; Doshi, V. Predictive Ability of a Predischarge Hour-specific Serum Bilirubin for and Near-term Newborns. Pediatrics 1999, 103, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.; Hammerman, C. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: A hidden risk for kernicterus. Semin. Perinatol. 2004, 5, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, V. Jaundice Due to Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency. NeoReviews 2012, 3, e166–e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.J. Predictive models for neonatal follow-up serum bilirubin: Model development and validation. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e21222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayeri, F.; Nili, F. Hypothermia at Birth and its Associated Complications in Newborns: A Follow up Study. Iran. J. Public Health 2006, 35, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, C.; Li, J.; Khine, M. Noninvasive Vital Signs Monitoring in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2024, 5, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adugna, A.; Ado, D. Determinants of Jaundice Among Neonates Admitted to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of Mizan Tepi University Teaching Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia, 2021: Unmatched Case Control Study. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2023, 10, 2333794X231218193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiha, U.; Banerjee, D.S.; Mandal, S. Demystifying non-invasive approaches for screening jaundice in low resource settings: A review. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1292678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Teeple, S.; Kassebaum, N.J. The contribution of neonatal jaundice to global child mortality: Findings from the GBD 2016 Study. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20171471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniusas, E. Biomedical Signals and Sensors I; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-642-24842-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sazonov, E. Wearable Sensors: Fundamentals, Implementation and Applications, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 978-0-128-19247-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, B.; Goldstein, B.A.; Kibbe, W.A.; Dunn, J.P. Investigating sources of inaccuracy in wearable optical heart rate sensors. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crivellaro, F.; Costa, A.; Vieira, P. Comparative Analysis of Short-range Wireless Technologies for m-Health: Newborn Monitoring Case Study. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Wireless Networks and Mobile Systems (WINSYS 2021), Setúbal, Portugal, 26–28 July 2021; pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Crivellaro, F.; Costa, A.; Vieira, P. Signal Quality in Continuous Transcutaneous Bilirubinometry. Sensors 2024, 24, 6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajinov, Z.; Matić, M.; Prćić, S.; Đuran, V. Optical properties of the human skin. Serbian J. Dermatol. Venerol. 2010, 2, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setchfield, K.; Gorman, A.; Simpson, A.H.R.W.; Somekh, M.G.; Wright, A.J. Effect of skin color on optical properties and the implications for medical optical technologies: A review. J. Biomed. Opt. 2024, 29, 010901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchin, V.V. Tissue Optics: Light Scattering Methods and Instruments for Medical Diagnosis, 3rd ed.; Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE): Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-162-84-1516-2. [Google Scholar]

- Keiser, G. Biophotonics: Concepts to Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2016; ISBN 978-981-10-0945-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, S.L. Method and Apparatus for Optical Measurement of Bilirubin in Tissue. U.S. Patent 5,353,790, 11 October 1994. Available online: https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/cd/9b/26/f5c1b32d35d528/US5353790.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Twersky, V. Multiple Scattering of Waves and Optical Phenomena. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1962, 52, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.M.; Sekelj, P. Light-absorbing and Scattering Properties of Nonhaemolysed Blood. Phys. Med. Biol. 1967, 12, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpy, D.T.; Cope, M.; van der Zee, P.; Arridge, S.; Wray, S.; Wyatt, J. Estimation of optical pathlength through tissue from direct time of flight measurement. Phys. Med. Biol. 1988, 33, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshina, I.; Spigulis, J. Beer–Lambert law for optical tissue diagnostics: Current state of the art and the main limitations. J. Biomed. Opt. 2021, 26, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, S.L.; Saidi, I.S.; Ladner, A.; Oelberg, D. Developing an optical fiber reflectance spectrometer to monitor bilirubinemia in neonates. In Optical Fibers and Sensors for Medical Diagnostics and Treatment Monitoring II; Jacques, S.L., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1997; Volume 2976, pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Blois, M.S. On the Spectroscopic Properties of Some Natural Melanins. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1966, 47, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsink, C.F.; Dam-Vervloet, A.J.; Krommendijk, M.E.; Kaya, M.; Cuartas-Vélez, C.; Knop, T.; Francis, K.J.; Bosschaart, N. Design and characterization of color printed polyurethane films as biomedical phantom layers. Biomed. Opt. Express 2023, 14, 4485–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustari, A.; Nishidate, I.; Wares, M.A.; Maeda, T.; Kawauchi, S.; Sato, S.; Sato, M.; Aizu, Y. Agarose-based Tissue Mimicking Optical Phantoms for Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 138, 57578. [Google Scholar]

- Karamavuş, Y.; Özkan, M. Newborn jaundice determination by reflectance spectroscopy using multiple polynomial regression, neural network, and support vector regression. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2019, 51, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam-Vervloet, A.J.; van Erk, M.D.; Doorn, N.; Lip, S.G.J.; Timmermans, N.A.; Vanwinsen, L.; de Boer, F.; van Straaten, H.L.M.; Bosschaart, N. Inter-device reproducibility of transcutaneous bilirubin meters. Ped. Res. 2021, 89, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosschaart, N.; Mentink, R.; Kok, J.H.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Aalders, M.C. Optical properties of neonatal skin measured in vivo as a function of age and skin pigmentation. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 097003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, A.R.; Newman, T.B.; Slaughter, J.L.; Maisels, M.J.; Watchko, J.F.; Downs, S.M.; Grout, R.W.; Bundy, D.G.; Stark, A.R.; Bogen, D.L.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline Revision: Management of Hyperbilirubinemia in the Newborn Infant 35 or More Weeks of Gestation. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022058859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draeger Medical Systems, Inc. Jaundice Meter JM-105 Datasheet. Available online: https://www.draeger.com/Content/Documents/Products/jaundice-meter-jm-105-pi-9068226-en-gb_intended%20use.pdf#page=4.21 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- van Erk, M.D.; Dam-Vervloet, A.J.; de Boer, F.; Boomsma, M.F.; van Straaten, H.L.M.; Bosschaart, N. How skin anatomy influences transcutaneous bilirubin determinations: An in vitro evaluation. Ped. Res. 2019, 86, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, P.; Varandas, R.; Gamboa, H. Machine Learning Algorithm Development and Metrics Extraction from PPG Signal for Improved Robustness in Wearables. In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTECH), Lisbon, Portugal, 16–18 February 2023; INSTICC: Setúbal, Portugal, 2023; pp. 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher, S.; Vieluf, S.; Bruno, E.; Joseph, B.; Epitashvili, N.; Biondi, A.; Zabler, N.; Glasstetter, M.; Dümpelmann, M.; Van Laerhoven, K.; et al. Data quality evaluation in wearable monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsack, J.C.; Coravos, A.; Bakker, J.P.; Bent, B.; Dowling, A.V.; Fitzer-Attas, C.; Godfrey, A.; Godino, J.G.; Gujar, N.; Izmailova, E.; et al. Verification, analytical validation, and clinical validation (V3): The foundation of determining fit-for-purpose for Biometric Monitoring Technologies (BioMeTs). npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Imosemi, D.O.; Emokpae, A.A. Differences Between Transcutaneous and Serum Bilirubin Measurements in Black African Neonates. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamori, G.; Kamoto, U.; Nakamura, F.; Isoda, Y.; Uozumi, A.; Matsuda, R.; Shimamura, M.; Okubo, Y.; Ito, S.; Ota, H. Neonatal wearable device for colorimetry-based real-time detection of jaundice with simultaneous sensing of vitals. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Ibrahim, N.R.; Ramli, N.; Abdul Majid, N.; Yacob, N.M.; Nasir, A. Comparison between the Transcutaneous and Total Serum Bilirubin Measurement in Malay Neonates with Neonatal Jaundice. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 29, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description | CCC |

|---|---|

| JM-105 (75%) and ProtoBili | 0.95 |

| JM-105 (50%) and ProtoBili | 0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crivellaro, F.; Pedroso, A.I.S.; Costa, A.; Vieira, P. Wearable Multispectral Sensor for Newborn Jaundice Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 7293. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237293

Crivellaro F, Pedroso AIS, Costa A, Vieira P. Wearable Multispectral Sensor for Newborn Jaundice Monitoring. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7293. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237293

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrivellaro, Fernando, Ana Isabel Sousa Pedroso, Anselmo Costa, and Pedro Vieira. 2025. "Wearable Multispectral Sensor for Newborn Jaundice Monitoring" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7293. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237293

APA StyleCrivellaro, F., Pedroso, A. I. S., Costa, A., & Vieira, P. (2025). Wearable Multispectral Sensor for Newborn Jaundice Monitoring. Sensors, 25(23), 7293. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237293