RBF Neural Network-Aided Robust Adaptive GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation Algorithm in Urban Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental Principles of the Algorithm

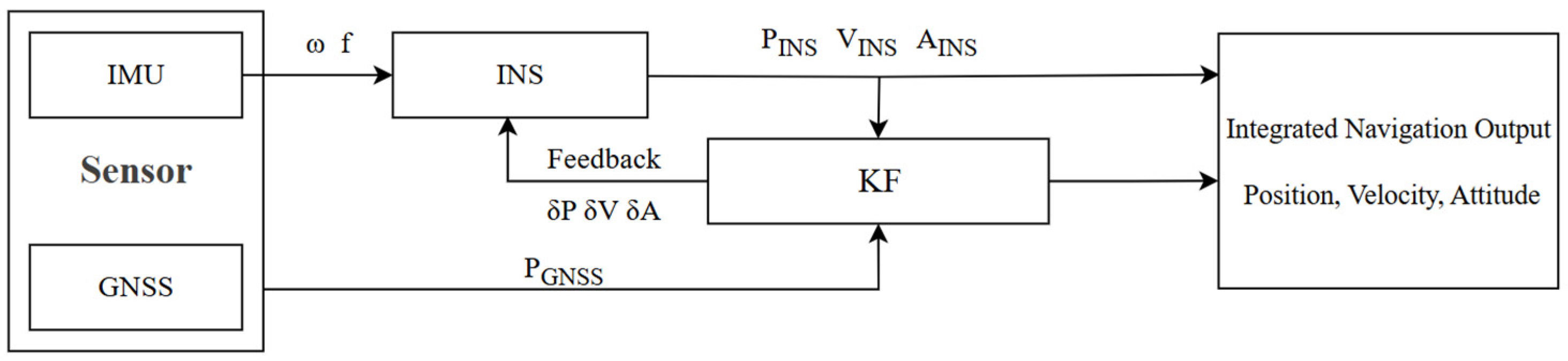

2.1. GNSS/INS Loosely Coupled Integrated Navigation System

2.2. Robust Adaptive Kalman Filter Based on an Improved Measurement Noise Covariance Matrix

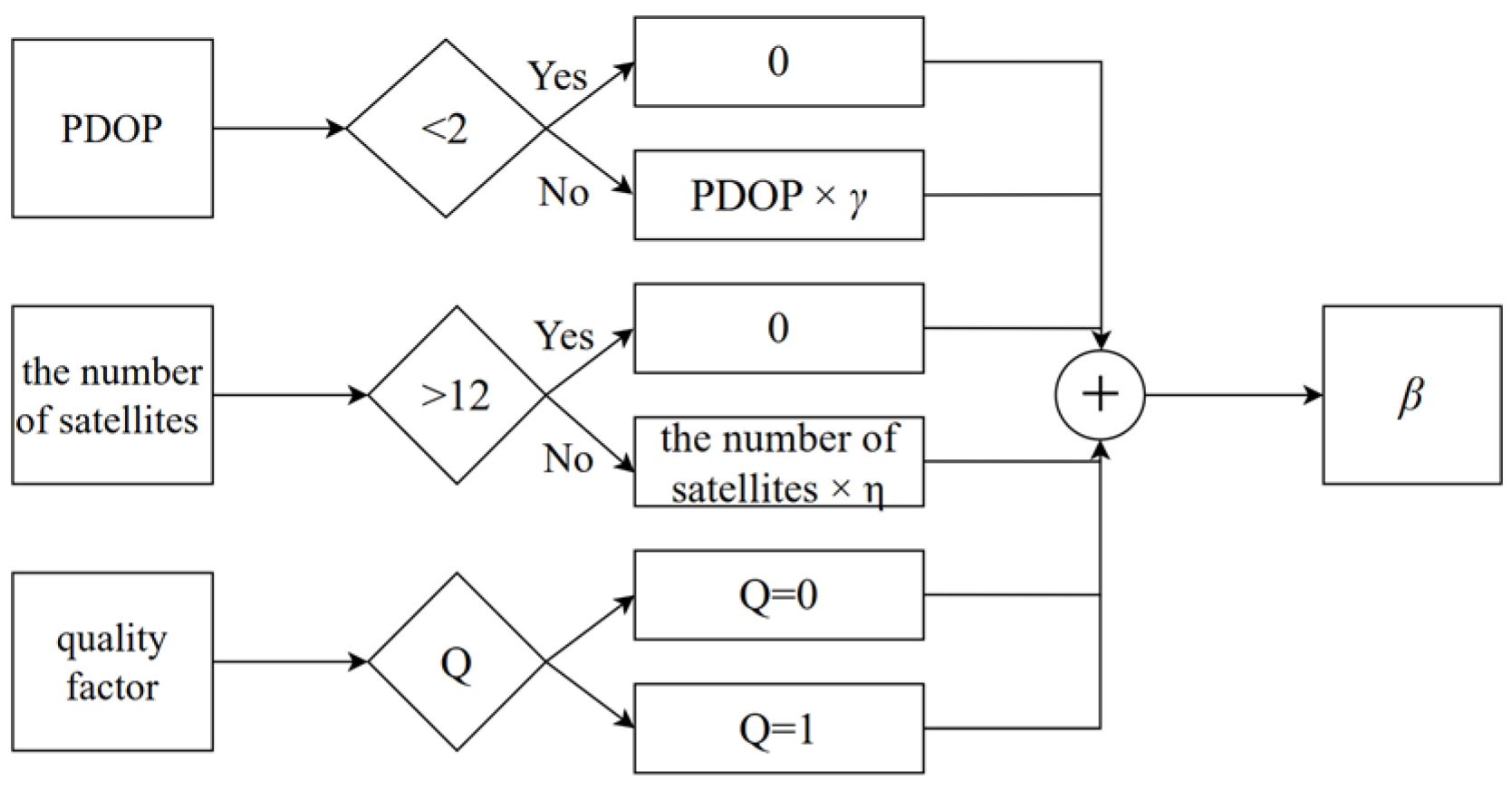

2.2.1. Multi-Criterion Optimized Measurement Noise Covariance Matrix

2.2.2. Robust Adaptive Kalman Filter Based on an Improved Measurement Noise Covariance Matrix

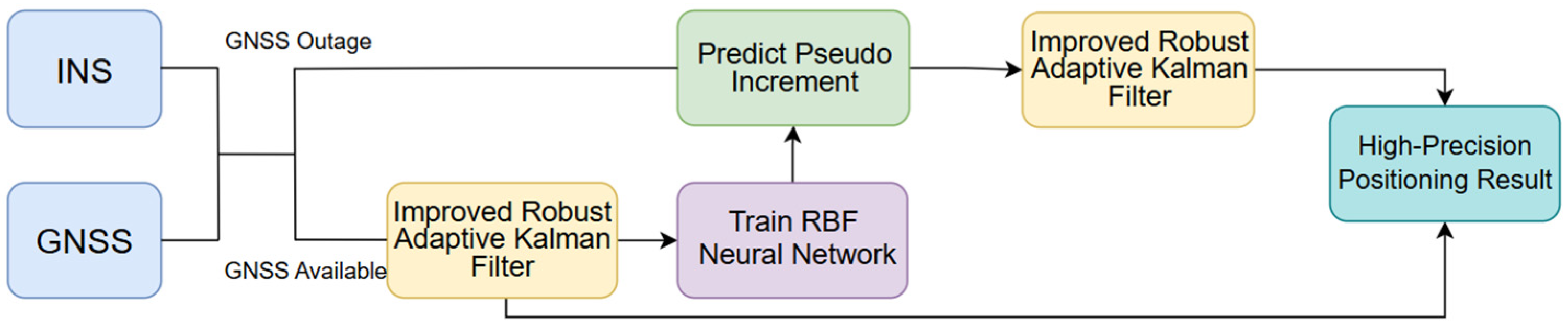

2.3. RBF Neural Network-Aided Robust Adaptive GNSS/INS-Integrated Navigation Algorithm

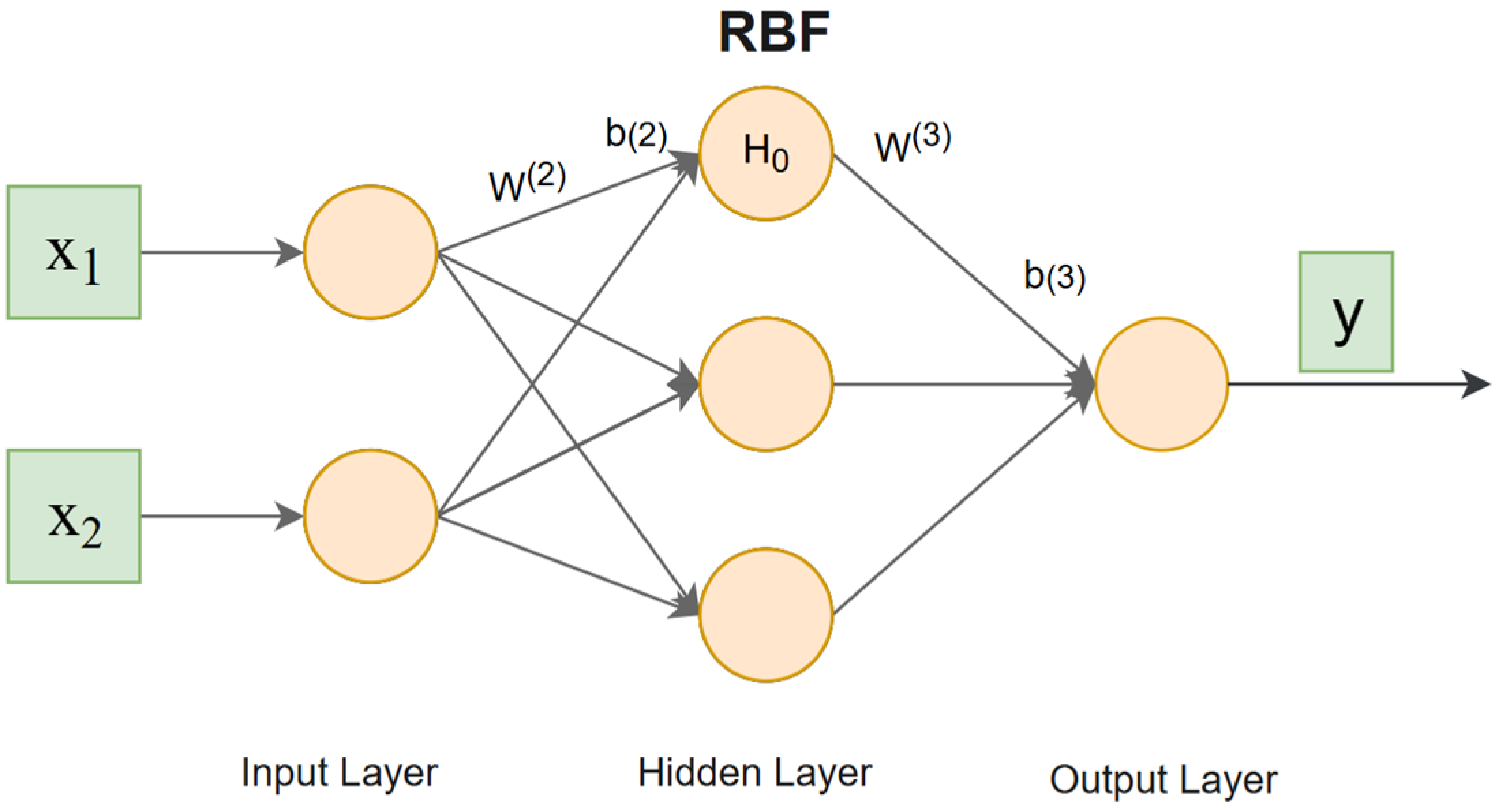

2.3.1. RBF Neural Network

2.3.2. RBF Neural Network-Aided Robust Adaptive GNSS/INS-Integrated Navigation Algorithm

- (a)

- When GNSS signals are available:

- ①

- The Robust Adaptive Kalman Filter is enhanced through improvements in the measurement noise covariance matrix to achieve high-accuracy navigation and positioning results, while simultaneously conducting RBF neural network training.

- ②

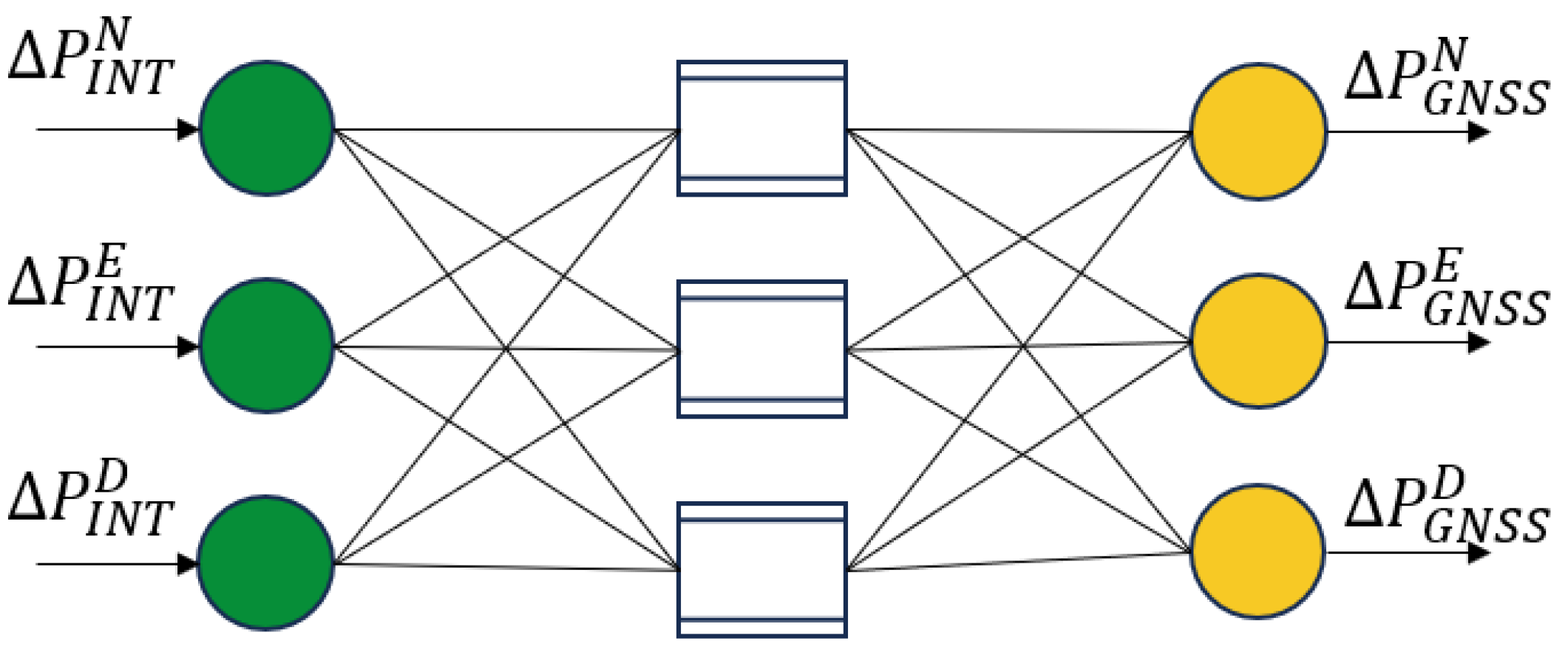

- Input dimension compression is achieved and training efficiency is enhanced by employing as the input–output mapping framework in the network topology design. The position increments from the integrated navigation system serve as the neural network input, while the GNSS position increments are designated as the target output for training the prediction model. The input and output layers are expressed as follows:where denotes the position increment output from the GNSS/INS-integrated system during the training period; represents the reference position increment from the GNSS navigation system, which is a three-dimensional vector in the north, east, and down components; and denotes the corresponding sampling epoch. The inputs and outputs of the RBF neural network are shown in Figure 5.

- ③

- The centers of the RBF basis functions are determined using the K-means clustering algorithm. Through multiple experimental validations and comprehensive evaluation based on prediction mean squared errors (MSEs) and training time consumption, the number of hidden layer nodes is optimized to three. The neural network preset training target is set to 0.01 with 300 maximum iterations. The training process continuously adjusts weights and expansion factors between the input and output layers, aiming to minimize prediction errors and establish the optimal mapping relationship.

- (b)

- When GNSS signals are unavailable:

- ①

- Assuming the GNSS outage occurs at epoch , the position increments from INS mechanization are fed into the pre-trained RBF neural network model. This generates predicted pseudo-GNSS position increments as the output.

- ②

- The pseudo-measurements predicted by the RBF neural network are incorporated into the improved Robust Adaptive Kalman Filter. The final GNSS/INS-integrated navigation positioning result is thus obtained.

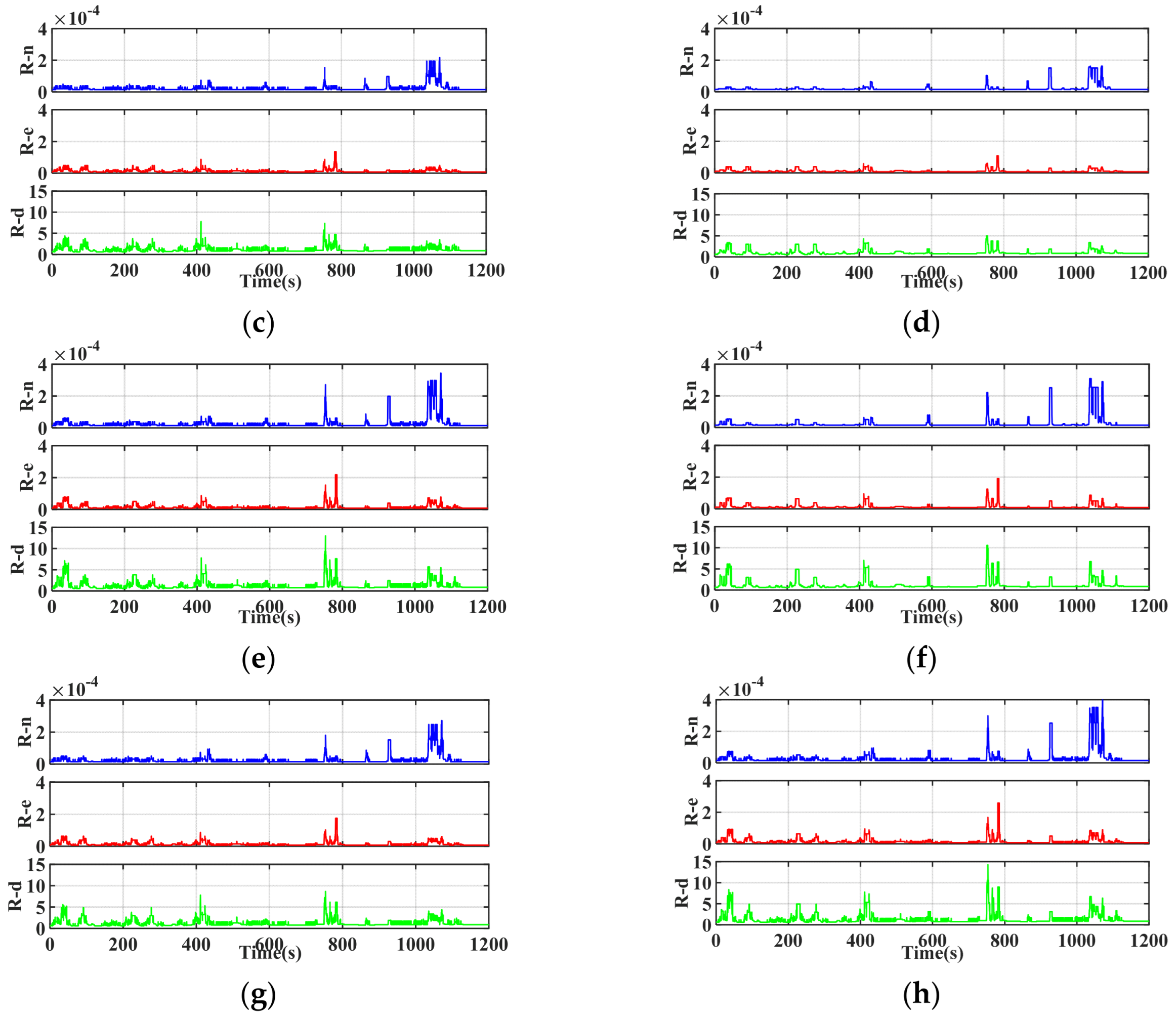

3. Robust Adaptive Filter with Improved Measurement Noise Matrix Testing

3.1. Data Collection

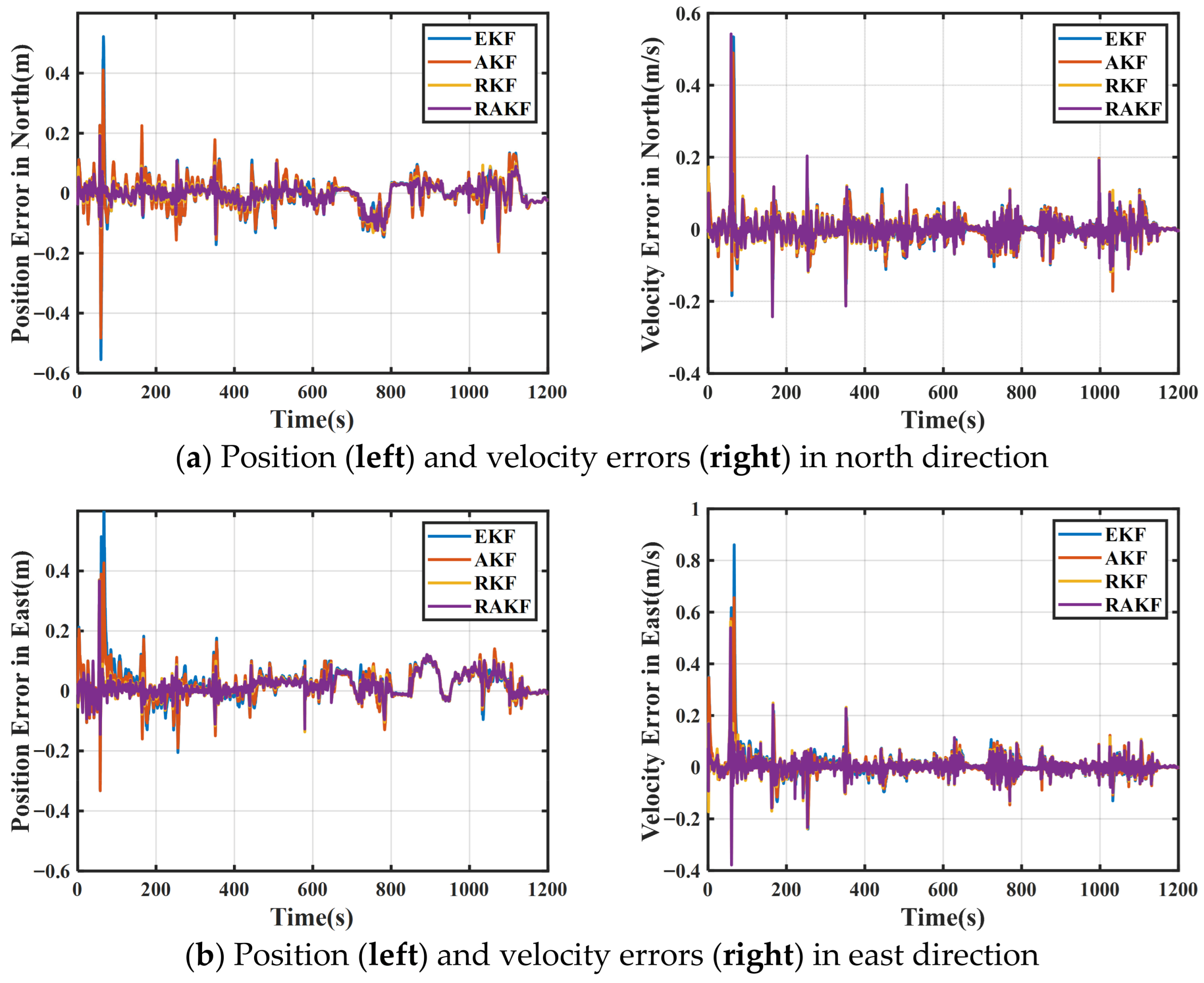

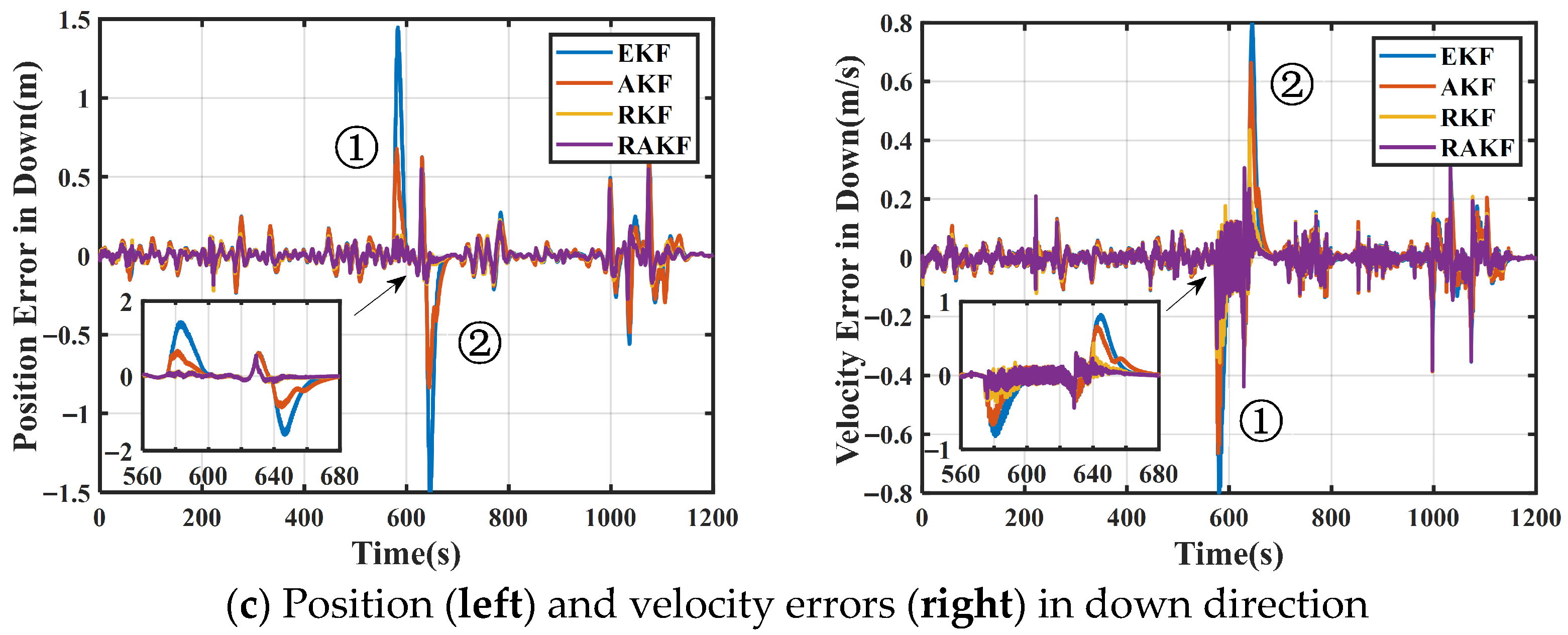

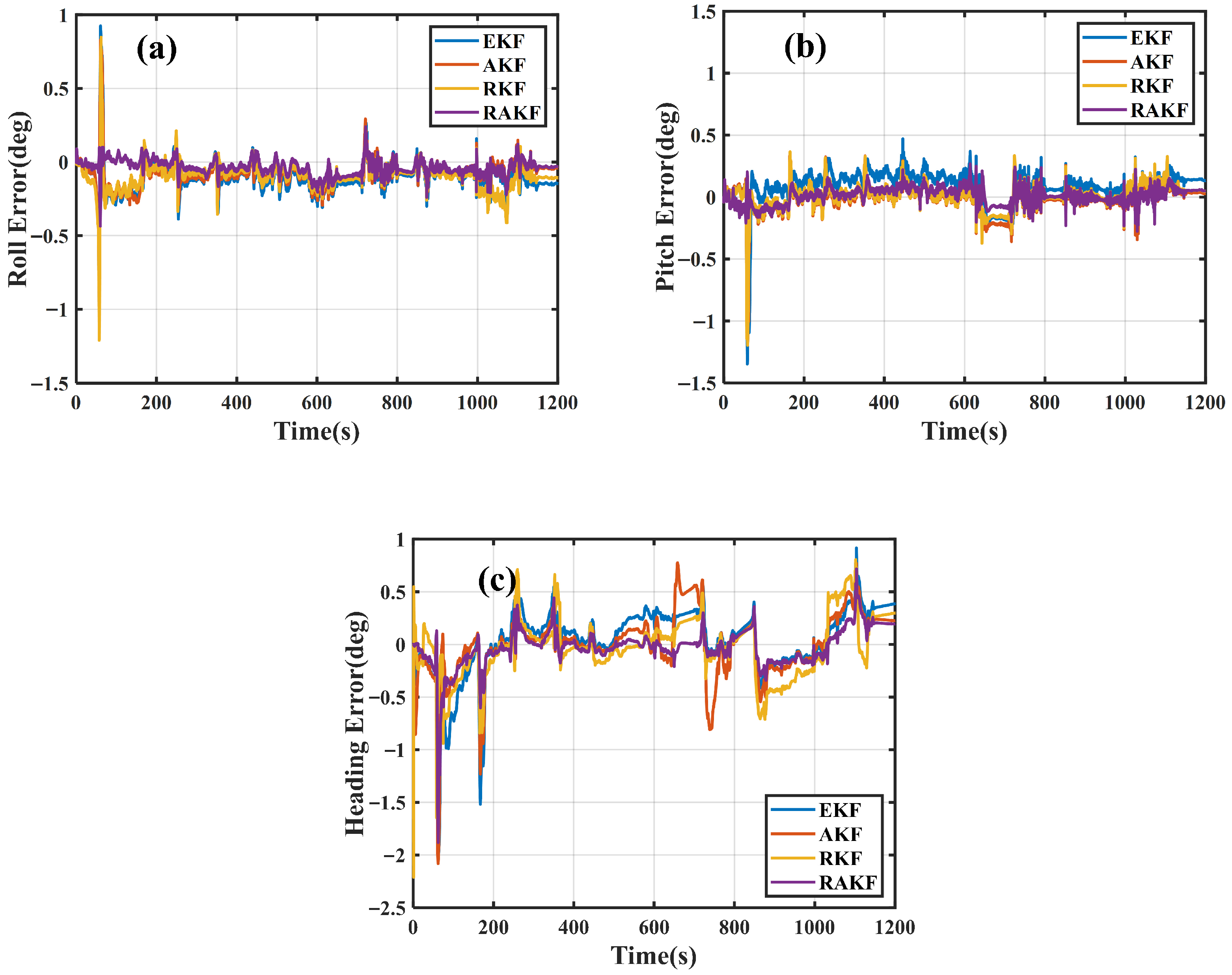

3.2. Experimental Results

4. RBF Neural Network-Aided Robust Adaptive Kalman Filter Testing

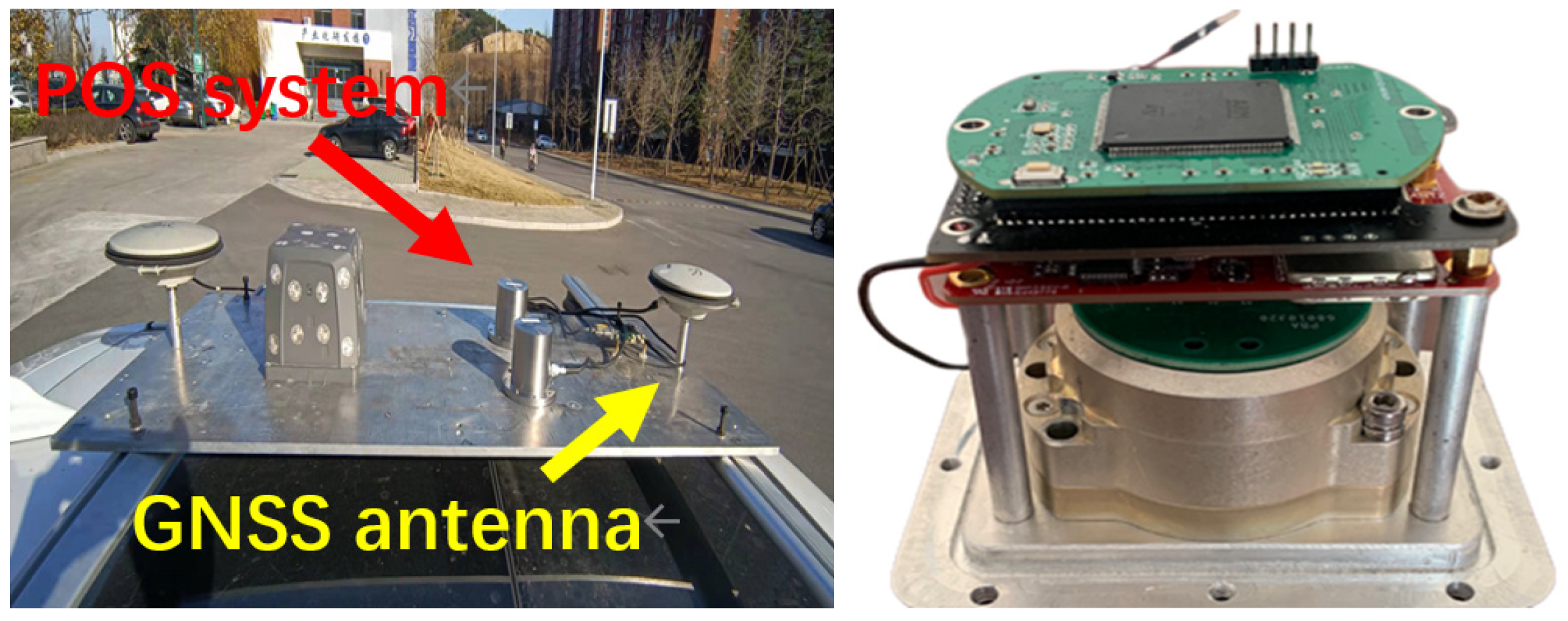

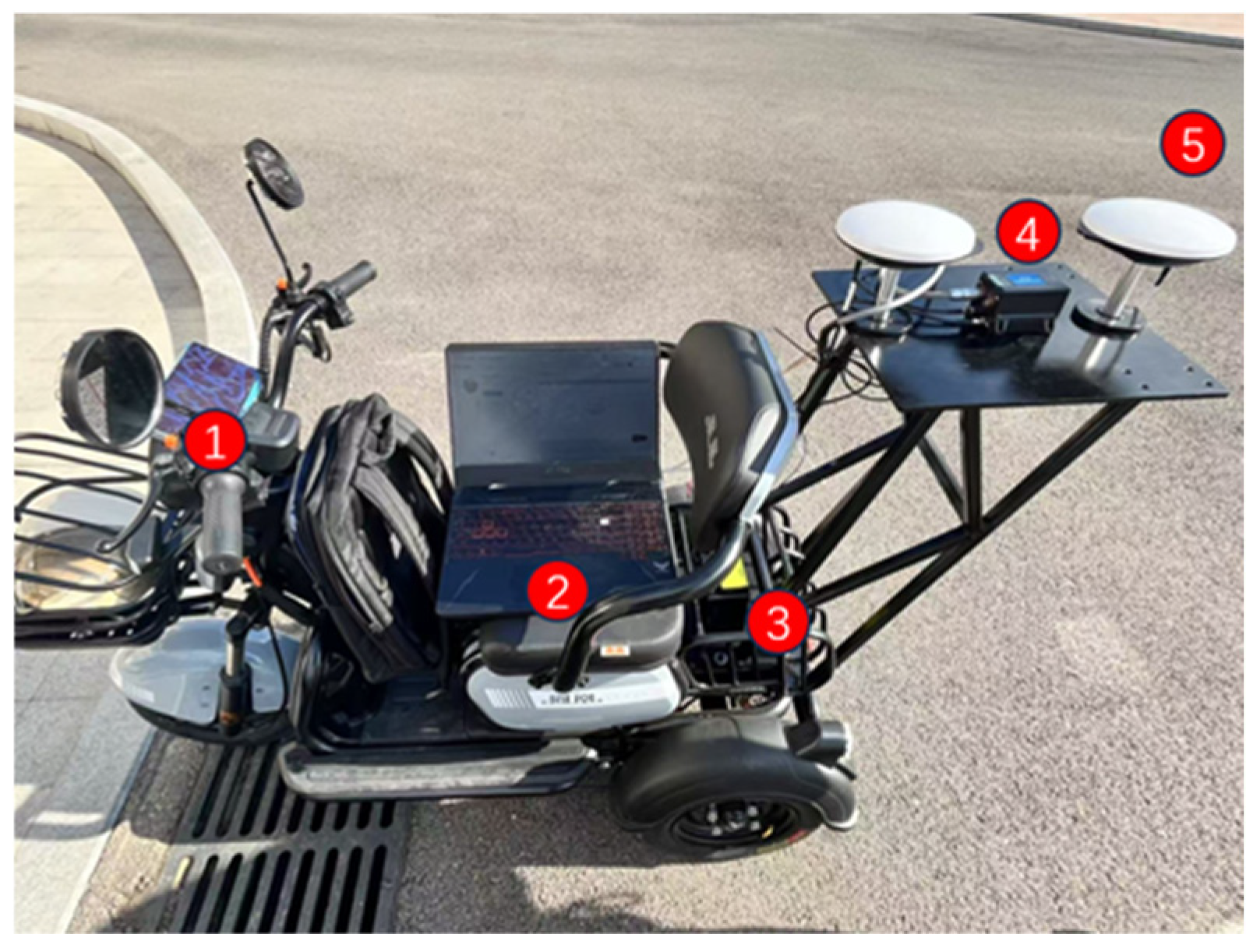

4.1. Experimental Platform

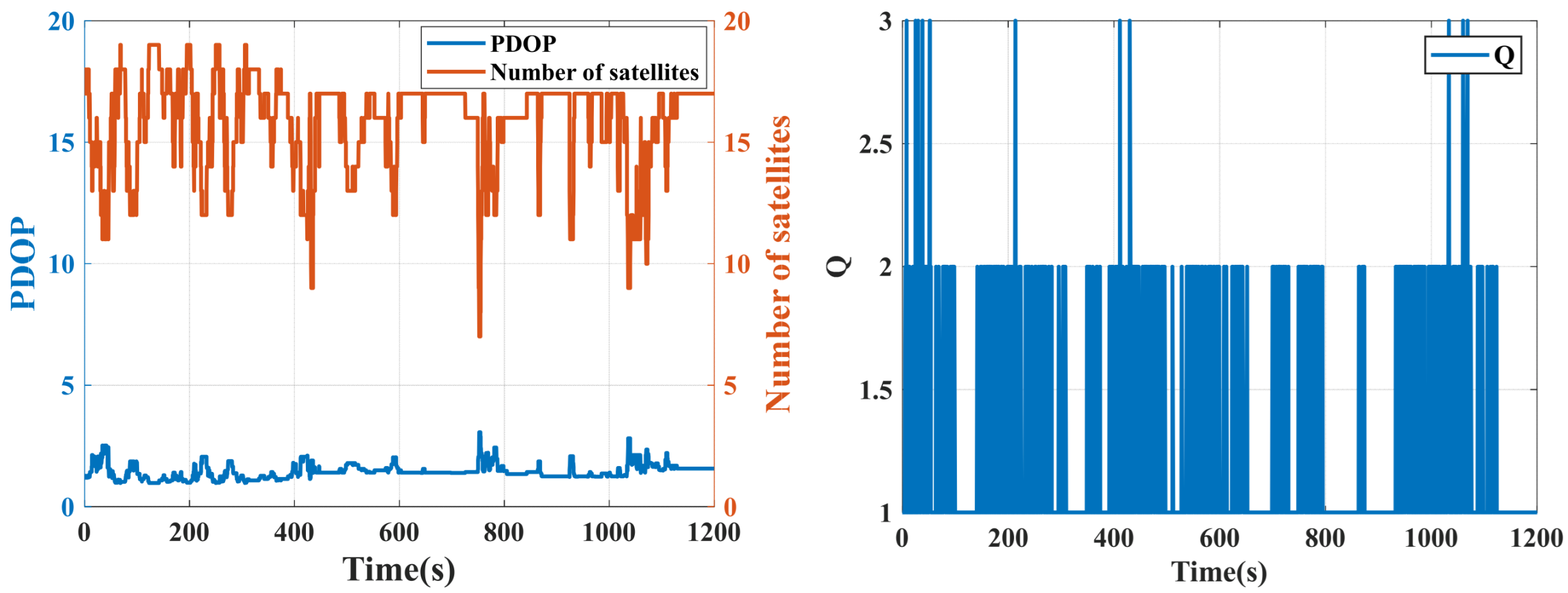

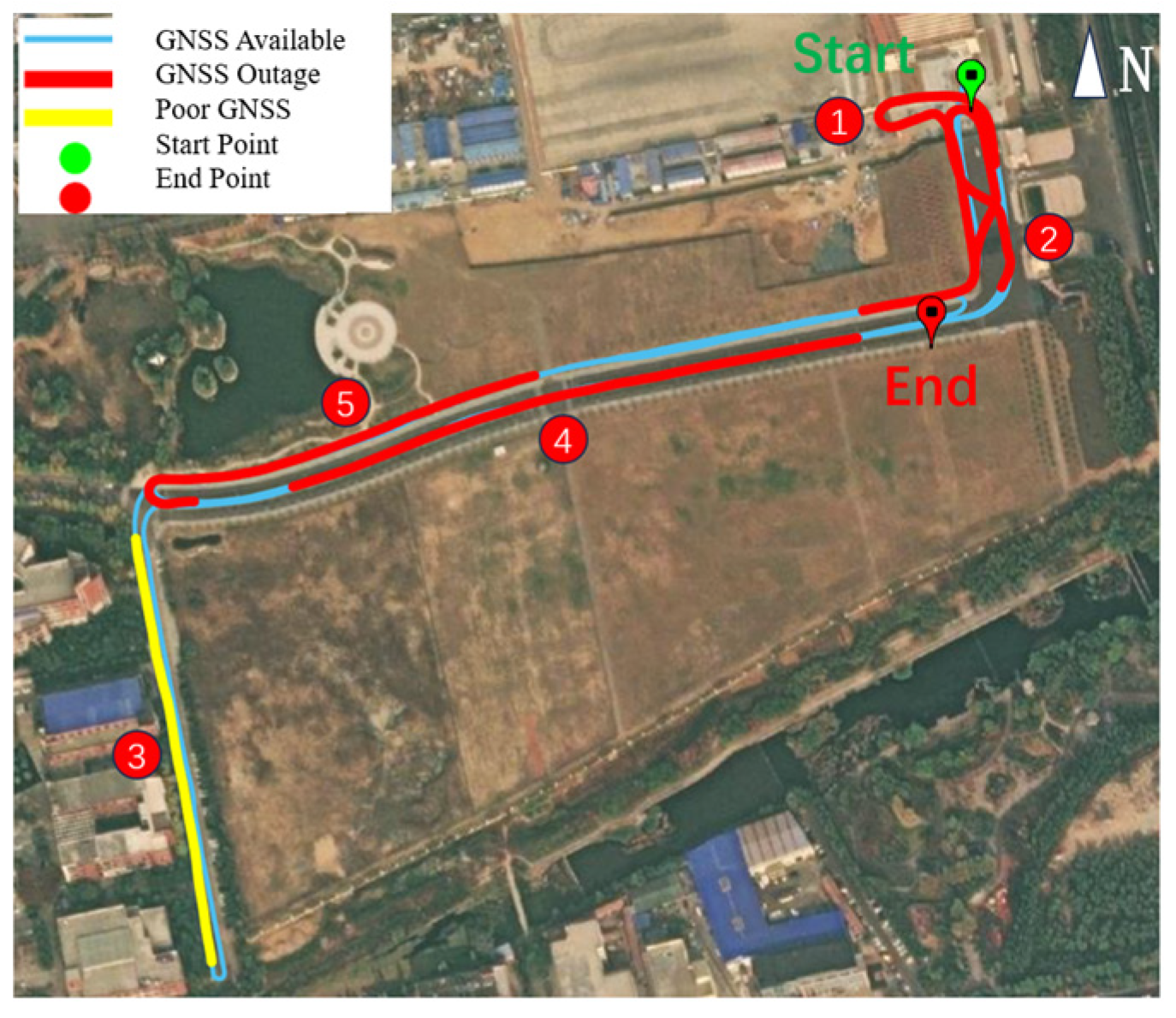

4.2. Experimental Design

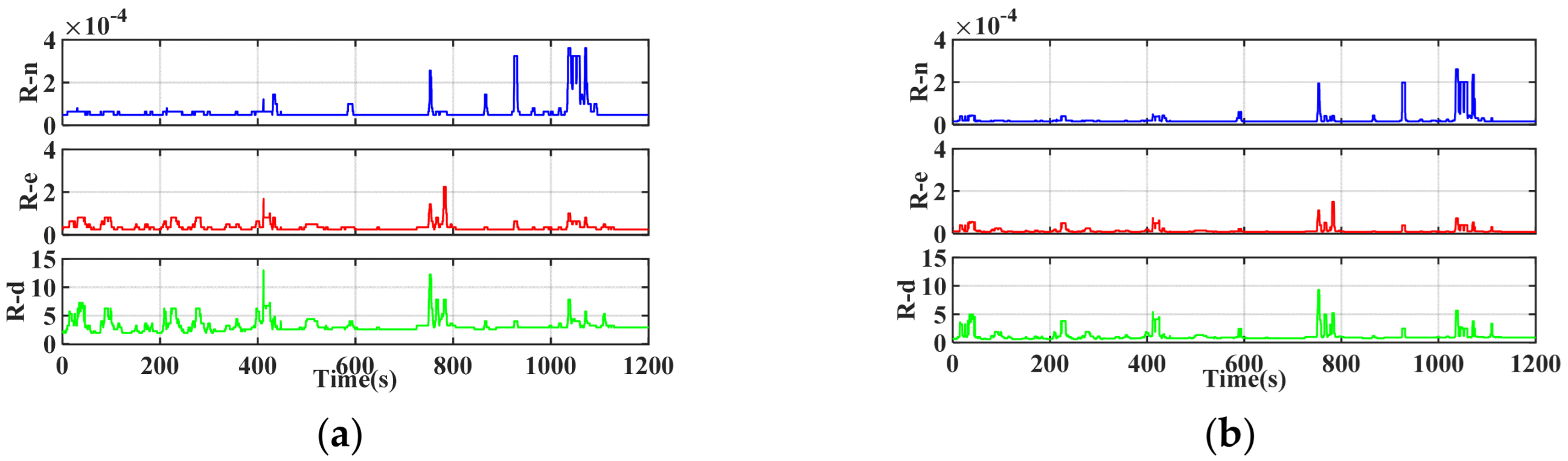

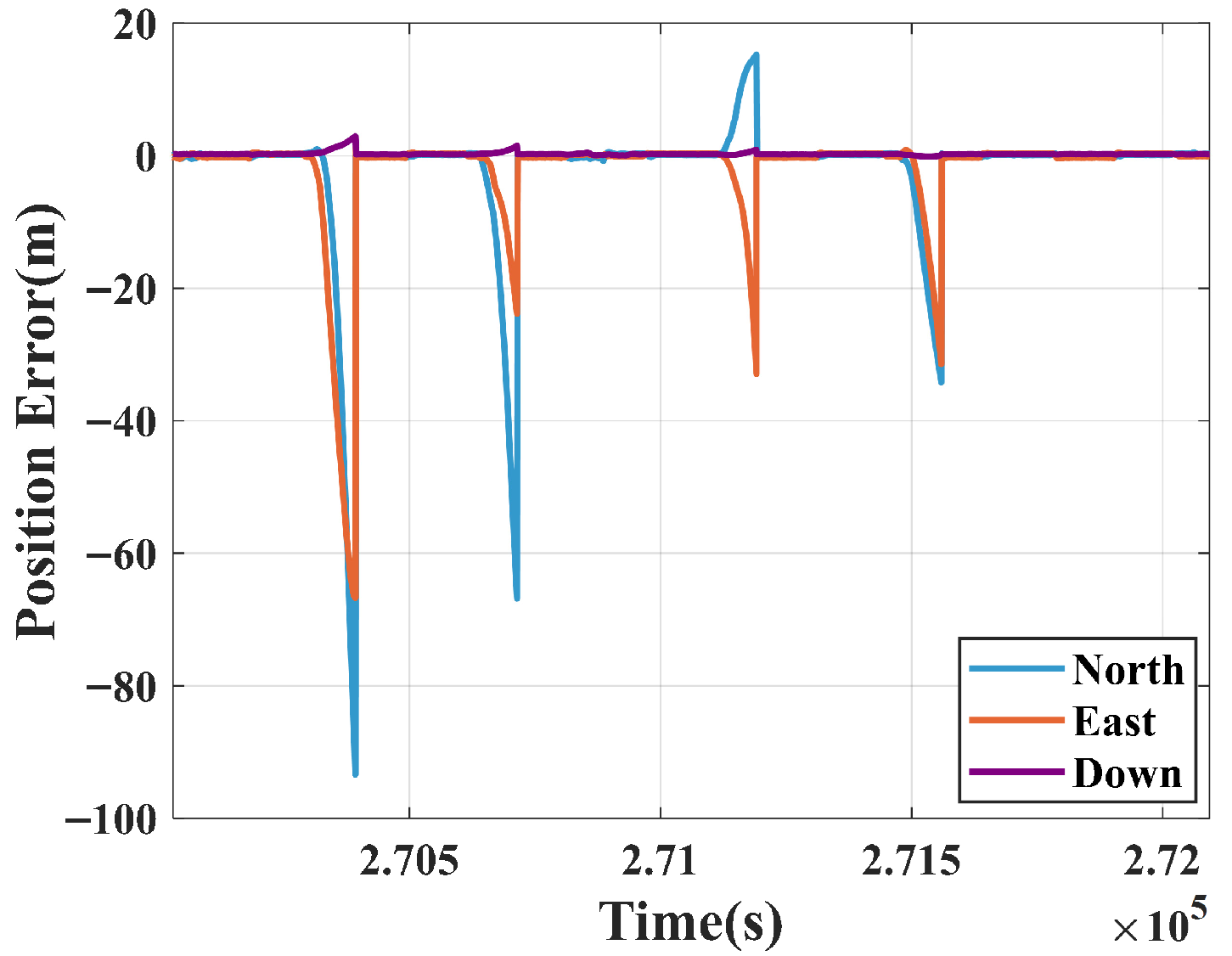

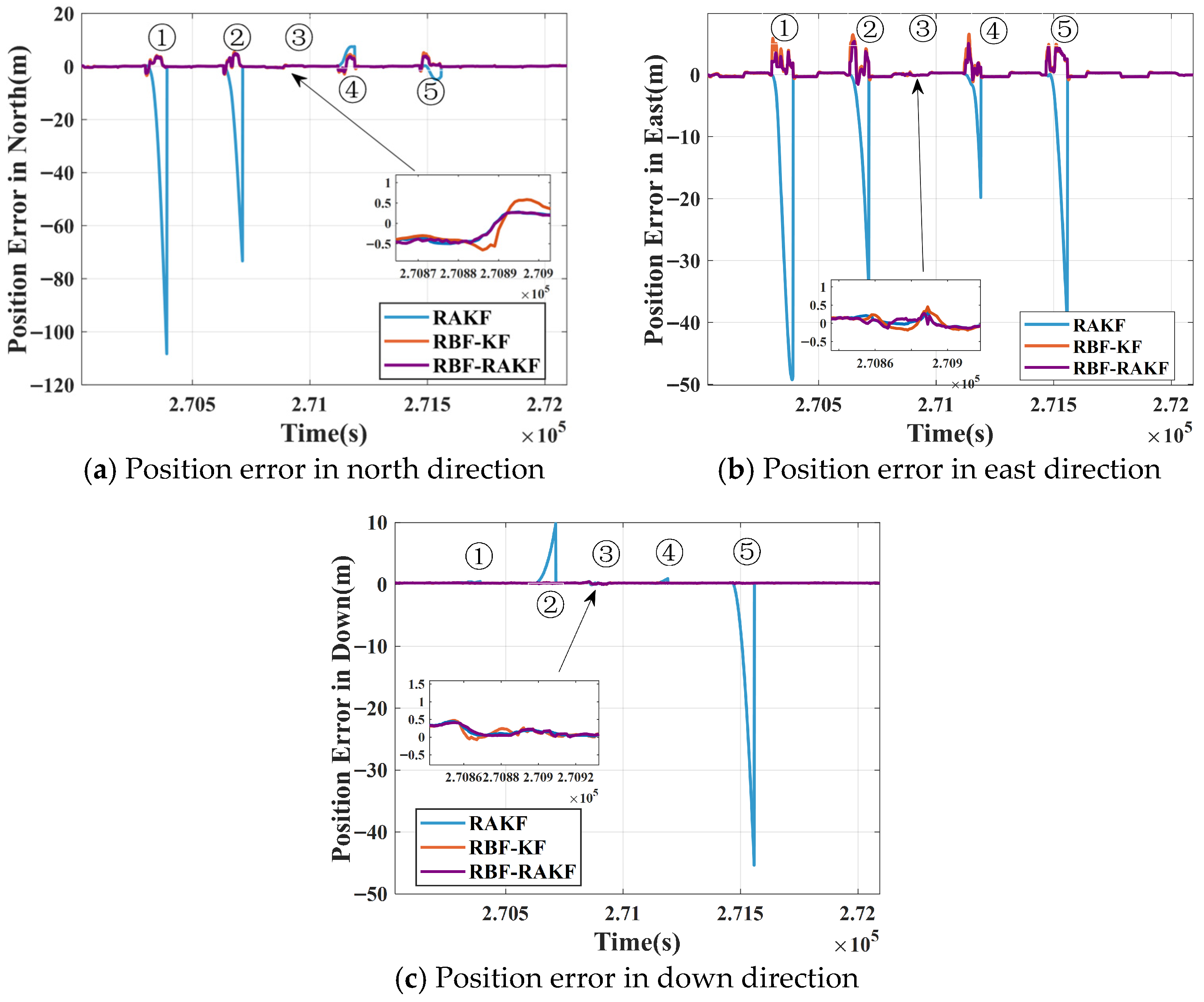

4.3. Experimental Results

- (1)

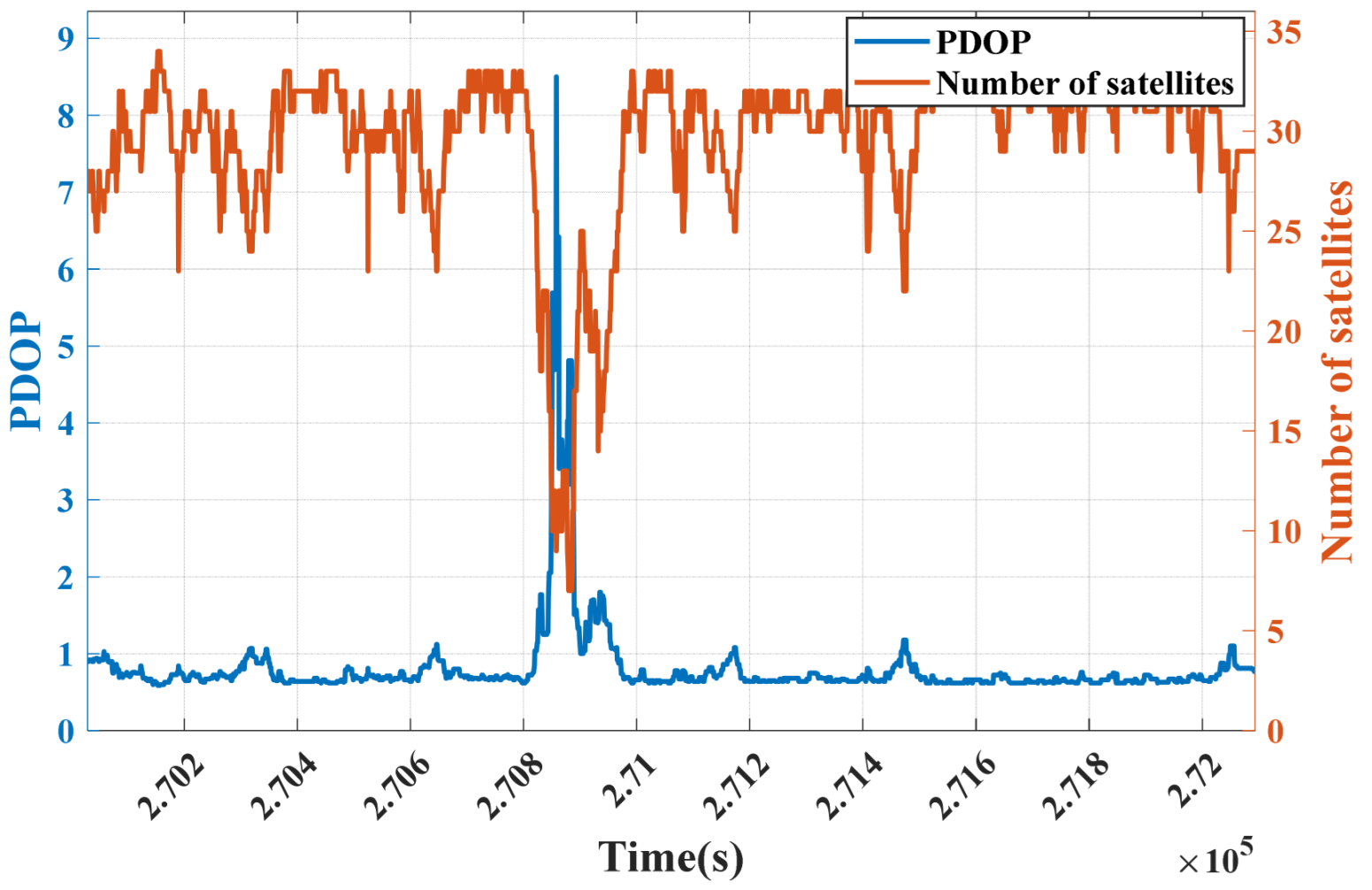

- The enhanced RAKF dynamically adjusts the measurement noise covariance matrix based on parameters like PDOP and the number of satellites. This reduces the weight of abnormal observations during GNSS signal fluctuations, effectively preventing filter divergence.

- (2)

- During the period when GNSS signals are available, the RBF neural network trains using high-precision navigation outputs from the improved Robust Adaptive Kalman Filter. During GNSS outages, INS data is used to predicts pseudo-position increments through the trained model of the RBF neural network. This scheme significantly suppresses the exponential accumulation of INS errors.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; Ren, X.; Yang, C. PNT Intelligent Services. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2021, 50, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Wang, J. A Novel Initial Alignment Scheme for Low-Cost INS Aided by GPS for Land Vehicle Applications. J. Navig. 2010, 63, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Concepts of Comprehensive PNT and Related Key Technologies. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2016, 45, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. An Adaptive Low-Cost GNSS/MEMS-IMU Tightly-Coupled Integration System with Aiding Measurement in a GNSS Signal-Challenged Environment. Sensors 2015, 15, 23953–23982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.; Zahran, S.; Moussa, A.; El-Sheimy, N.; Sesay, A. Radar and Visual Odometry Integrated System Aided Navigation for UAVS in GNSS Denied Environment. Sensors 2018, 18, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Yang, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Chai, D.; Cui, H. A Robust Adaptive Extended Kalman Filter Based on an Improved Measurement Noise Covariance Matrix for the Monitoring and Isolation of Abnormal Disturbances in GNSS/INS Vehicle Navigation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Chen, M.; Shi, X.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, W.; Tong, S. A Fast Satellite Selection Method Based on the Multi-Strategy Fusion Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm for Low Earth Orbit Satellites. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Lv, C.; Wu, J.; Li, L.; Ding, D. An Innovative Information Fusion Method with Adaptive Kalman Filter for Integrated INS/GPS Navigation of Autonomous Vehicles. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 100, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, S.; Yao, C.; Wang, Y.; Ding, K. A Novel Real-Time Integrated Navigation System Based on the S-Transformer and A-SRCKF During GPS Outages. GPS Solut. 2025, 29, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Filtering Algorithms and Reliability Analysis for GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation Systems. Cehui Xuebao 2020, 49, 1376. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, P.S.; Gary, W.H. Adaptive Filtering with Unknown Prior Statistics. In Proceedings of the Joint Automatic Control Conference, Boulder, CO, USA, 5–7 August 1969; pp. 760–769. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Yang, Y. The Improved Method of Sage Adaptive Filtering. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 2000, 25, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, W. An Optimal Adaptive Kalman Filter. J. Geod. 2006, 80, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, H.W.; Sacks, J.E. Recursive Fading Memory Filtering. Inf. Sci. 1971, 3, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhang, X. Robust Kalman Filtering with Constraints: A Case Study for Integrated Navigation. J. Geod. 2010, 84, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X. Weiwei Sun Sage-Husa Adaptive Kalman Filtering Algorithm for GNSS/SINS Integrated Navigation System Based on Exponential Weighted Average. J. Geod. Geodyn. 2024, 44, 1287–1292, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Jiang, J.; Pang, X.; Ge, Z. Application of Improved Fault Detection and Robust Adaptive Algorithm in GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, H.; Li, Y. Vehicle State Estimation Based on Sage–Husa Adaptive Unscented Kalman Filtering. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.J. Robust Estimation of a Location Parameter. In Breakthroughs in Statistics; Kotz, S., Johnson, N.L., Eds.; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 492–518. ISBN 978-0-387-94039-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zengke, L.; Yifei, Y.; Jian, W.; Jingxiang, G. Application of Improved Robust Kalman Filter in Data Fusion for PPP/INS Tightly Coupled Positioning System. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 2017, 24, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y. Fog Random Drift Signal Denoising Based on the Improved AR Model and Modified Sage-Husa Adaptive Kalman filter. Sensors 2016, 16, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Shao, K. Improved Robust and Adaptive Filter Based on Non-Holonomic Constraints for RTK/INS Integrated Navigation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Yang, X.; Hu, C.; Li, W. Improved Forward and Backward Adaptive Smoothing Algorithm. GPS Solut. 2022, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Jia, Y. Location of Mobile Station With Maneuvers Using an IMM-Based Cubature Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 59, 4338–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Hu, G.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, X. Cubature Kalman Filter With Both Adaptability and Robustness for Tightly-Coupled GNSS/INS Integration. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 14997–15011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y. Research on the SSUKF Integrated Navigation Algorithm Based on Adaptive Factors. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wu, F. Adaptive Integrated Navigation Based Artificial Intelligence. J. Beijing Univ. Posts Telecommun. 2021, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; He, Z.; Wang, D. SINS/CNS/GNSS Integrated Navigation Based on an Improved Federated Sage–Husa Adaptive Filter. Sensors 2019, 19, 3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jianwei, L.; Zhiyan, S. Overview of Recurrent Neural Networks. Kongzhi Yu Juece 2022, 37, 2753–2768. [Google Scholar]

- Jwo, D.-J.; Biswal, A.; Mir, I.A. Artificial Neural Networks for Navigation Systems: A Review of Recent Research. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Wang, J.; Jin, S.; Meng, X. GA-SVR and Pseudo-Position-Aided GPS/INS Integration during GPS Outage. J. Navig. 2015, 68, 678–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, X. A RLS-SVM Aided Fusion Methodology for INS during GPS Outages. Sensors 2017, 17, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, W.; Jiang, J.; Lu, S.; Gong, Y.; Tao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yan, P.; Luo, H.; Liu, J. A LSTM Algorithm Estimating Pseudo Measurements for Aiding INS during GNSS Signal Outages. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, K.; Jiang, C.; Li, Z.; Yang, C.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H. Motion-Constrained GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation Method Based on BP Neural Network. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, C.; Li, Z.; Zhou, F.; Liu, D. GNSS/INS/OD/NHC Adaptive Integrated Navigation Method Considering the Vehicle Motion State. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 13511–13523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, J.; Yan, P.; Tao, Y.; Liu, J. A GRU and AKF-Based Hybrid Algorithm for Improving INS/GNSS Navigation Accuracy during GNSS Outage. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Han, H.; Wang, J.; Xiao, X.; Li, D.; Chen, C.; Wang, L. Enhanced CNN-BiLSTM-Attention Model for High-Precision Integrated Navigation During GNSS Outages. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Kong, X.; Xu, H.; Li, H. INS-GNSS Integrated Navigation Algorithm Based on TransGAN. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2023, 37, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Fang, J.; He, J.; Ma, S.; Wen, G.; Li, Z. GRU–Transformer Hybrid Model for GNSS/INS Integration in Orchard Environments. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Hu, G.; Gao, S.; Zhong, Y.; Gu, C. Multi-Sensor Optimal Data Fusion for INS/GNSS/CNS Integration Based on Unscented Kalman Filter. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2018, 16, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Qiu, M.; Wang, T.; Yao, X.; Cong, H.; Zhang, Y. Noise-Adaptive GNSS/INS Fusion Positioning for Autonomous Driving in Complex Environments. Vehicles 2025, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, N.L.; Wang, J. A Comparison of Outlier Detection Procedures and Robust Estimation Methods in GPS Positioning. J. Navig. 2009, 62, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbilgic, O.; Bozdogan, H.; Balaban, M.E. A Novel Hybrid RBF Neural Networks Model as a Forecaster. Stat. Comput. 2014, 24, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Performance Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Gyroscope Bias | 0.25°/h |

| Angular Random Walk | 0.04°/√h |

| Accelerometer Bias | 0.025 mg |

| Velocity Random Walk | 0.03 m/s/√h |

| Scheme | R Value |

|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | |

| Scheme 2 | |

| Scheme 3 | |

| Scheme 4 | |

| Scheme 5 | |

| Scheme 6 | |

| Scheme 7 | |

| Scheme 8 |

| Position (m) | Velocity (m/s) | Attitude (deg) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | 0.0590 | 0.0660 | 0.2060 | 0.0420 | 0.0580 | 0.1010 | 0.1470 | 0.1680 | 0.3260 |

| Scheme 2 | 0.0420 | 0.0481 | 0.1175 | 0.0311 | 0.0415 | 0.0669 | 0.1214 | 0.1426 | 0.2468 |

| Scheme 3 | 0.0422 | 0.0484 | 0.1260 | 0.0311 | 0.0416 | 0.0712 | 0.1220 | 0.1439 | 0.2469 |

| Scheme 4 | 0.0420 | 0.0481 | 0.1167 | 0.0310 | 0.0414 | 0.0662 | 0.1215 | 0.1425 | 0.2461 |

| Scheme 5 | 0.0425 | 0.0485 | 0.1280 | 0.0313 | 0.0417 | 0.0715 | 0.1221 | 0.1438 | 0.2469 |

| Scheme 6 | 0.0422 | 0.0483 | 0.1189 | 0.0312 | 0.0415 | 0.0671 | 0.1215 | 0.1424 | 0.2461 |

| Scheme 7 | 0.0425 | 0.0485 | 0.1273 | 0.0312 | 0.0417 | 0.0714 | 0.1221 | 0.1438 | 0.2463 |

| Scheme 8 | 0.0417 | 0.0480 | 0.1152 | 0.0309 | 0.0414 | 0.0666 | 0.1213 | 0.1427 | 0.2468 |

| Improved (%) | 29.32% | 27.27% | 44.07% | 26.43% | 28.62% | 34.06% | 17.48% | 15.06% | 24.3% |

| Position Errors (m) | Velocity Errors (m/s) | Attitude Errors (deg) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | E | D | N | E | D | Roll | Pitch | Heading | |

| EKF | 0.059 | 0.066 | 0.206 | 0.042 | 0.058 | 0.101 | 0.147 | 0.168 | 0.326 |

| AKF | 0.054 | 0.059 | 0.131 | 0.038 | 0.050 | 0.079 | 0.126 | 0.131 | 0.306 |

| RKF | 0.033 | 0.046 | 0.056 | 0.034 | 0.037 | 0.040 | 0.137 | 0.135 | 0.282 |

| RAKF | 0.032 | 0.046 | 0.053 | 0.030 | 0.033 | 0.035 | 0.065 | 0.092 | 0.191 |

| Performance Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Accelerometer Bias | 0.025 mg |

| Gyroscope Bias | 0.25°/h |

| Velocity Random Walk | 0.03 m/s/√h |

| Angular Random Walk | 0.04°/√h |

| IMU Sampling Rate | 100 Hz |

| GNSS Sampling Rate | 10 Hz |

| Scheme | North (m) | East (m) | Down (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EKF | 10.52 | 8.96 | 0.39 |

| RAKF | 11.90 | 8.01 | 4.58 |

| RBF-KF | 1.14 | 1.30 | 0.22 |

| RBF-RAKF | 0.94 | 1.02 | 0.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Li, R.; Tu, R.; Zhang, G.; Hong, J.; Li, F. RBF Neural Network-Aided Robust Adaptive GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation Algorithm in Urban Environments. Sensors 2025, 25, 7286. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237286

Wang J, Li R, Tu R, Zhang G, Hong J, Li F. RBF Neural Network-Aided Robust Adaptive GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation Algorithm in Urban Environments. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7286. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237286

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jin, Ruoyi Li, Rui Tu, Guangxin Zhang, Ju Hong, and Fangxin Li. 2025. "RBF Neural Network-Aided Robust Adaptive GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation Algorithm in Urban Environments" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7286. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237286

APA StyleWang, J., Li, R., Tu, R., Zhang, G., Hong, J., & Li, F. (2025). RBF Neural Network-Aided Robust Adaptive GNSS/INS Integrated Navigation Algorithm in Urban Environments. Sensors, 25(23), 7286. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237286