1. Introduction

Tea is a prominent non-alcoholic beverage in today’s society [

1,

2]. More than 3 billion people in 160 countries and regions like to drink tea. The global tea market was valued at nearly 200 billion U.S. dollars in 2020 and is expected to rise to over 318 billion U.S. dollars by 2025 [

3]. According to the processing techniques, there are six categories of tea: green, yellow, white, oolong, black, and dark tea [

4]. Tea can be categorized into bulk tea and famous tea. Bulk tea refers to products mainly sold in bulk, which are relatively inexpensive and produced in large quantities [

5]. At present, bulk tea is mainly plucked by mechanized production methods with the standard of “a bud with two leaves” and “a bud with three leaves” [

6]. Tea plucking machines for bulk tea adopt the “one size fits all” standard, which uses a reciprocating cutter to cut the entire tea canopy at a certain depth [

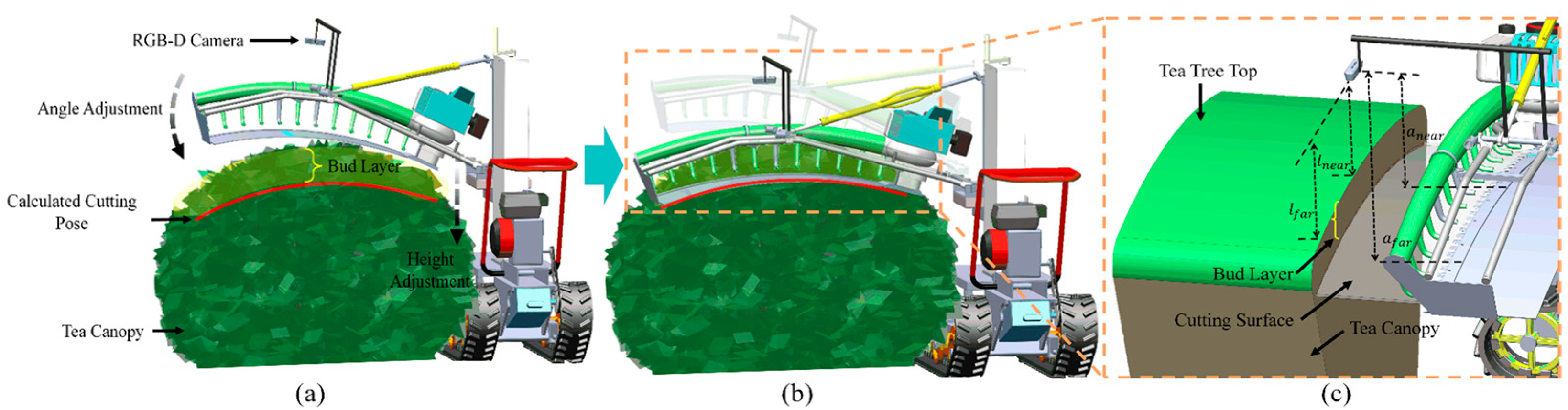

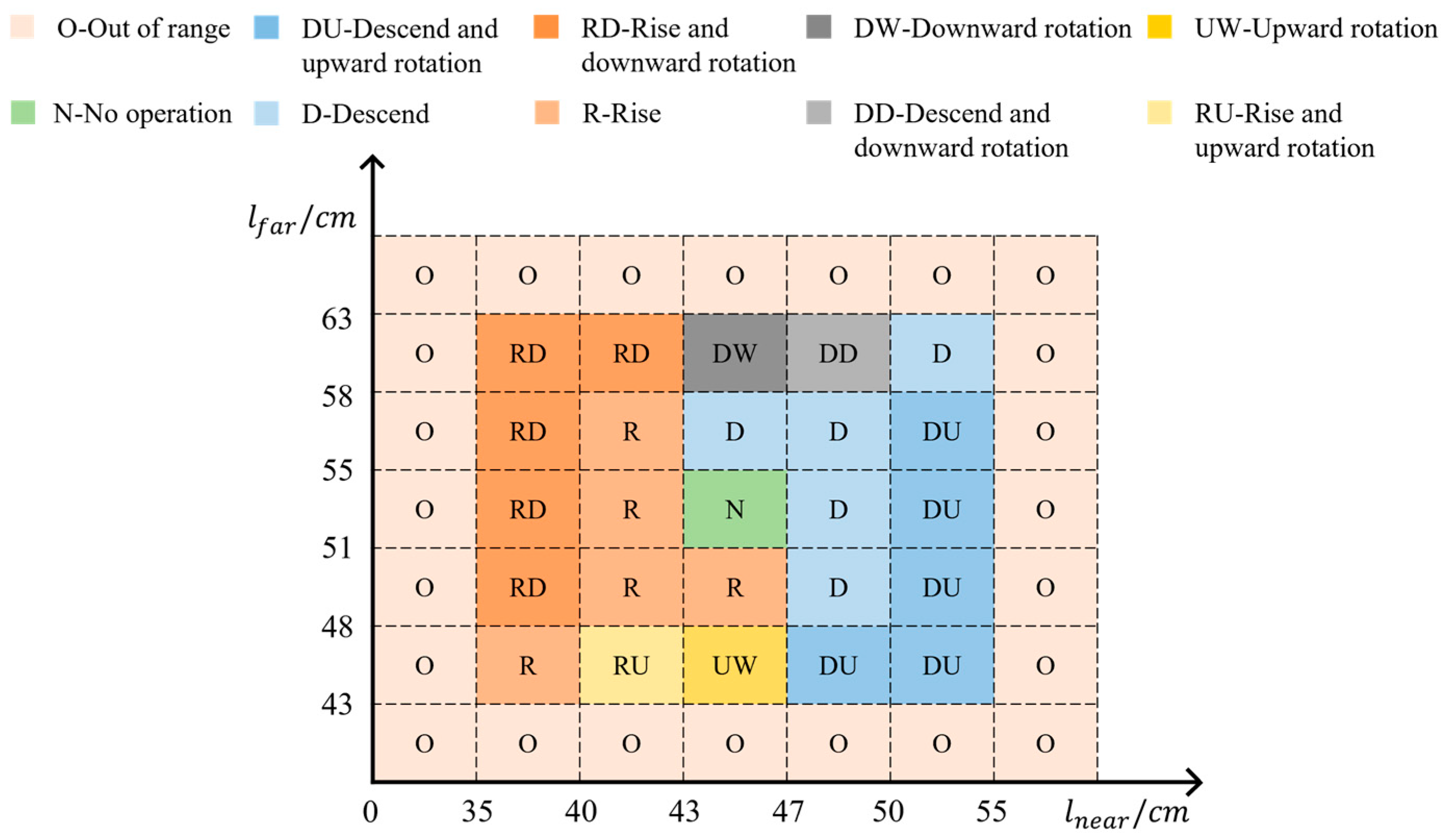

7]. When plucking bulk tea in tea plantations located on hilly terrains, the cutter requires real-time pose adjustments to adapt to the sloping terrain and the uneven growth of tea canopies. Therefore, the key to bulk tea harvesting is the cutter profiling of the tea canopy.

In recent years, there has been an emergence of tea plucking machines for bulk tea.

Figure 1 shows the structures of the tea plucking machine with single-carried, double-carried, self-propelled, and track riding type [

8]. The single-carried tea plucking machine has simple structure and convenience, but it is not suitable for large-scale tea plantations due to low operating efficiency [

9]. The double-carried tea plucking machine is the most prevalent, accounting for about 60% of the tea plucking machines used in China. However, the double-carried tea plucking machine requires two people to operate the machine and two people to coordinate the tea collecting bag, which is a high labor cost. Meanwhile, the noise, vibration, and hot gas emission during the oil-powered trimmer’s operation easily fatigues the operator. The combination of the self-propelled mobile platform and tea tree trimmer through a cantilever structure is the basic composition of the self-propelled tea plucking machine, which has the advantages of strong practicability and low cost [

10]. When the tea plucking machine with a riding type travels along the tracks on both sides of the tea rows, the cutter moves on the top of tea trees, which is suitable for tea plantations in the plains as well as on gentle slopes in the hills (below

) [

8]. Domestic tea plantations are primarily distributed in hilly areas characterized by intricate topography. Most tea plantations lack tractor roads and have specific slopes, making it challenging for tea plucking machines of riding type to adapt to such landscapes. Ensuring the cutter’s flexible adjustment is imperative because the cutter needs to be adjusted before each harvest to fit the tea canopy. A self-propelled tea plucking machine can adjust the height of the cutter by manually rotating the mechanical lifting mechanism to adapt to different heights of the tea canopy [

11]. The electric lift adjustment simplifies the operator’s manual adjustment of the cutter height by controlling it with two operating buttons [

12]. Nevertheless, the operation of driving the machine and manual adjustment of the lifting mechanism have certain drawbacks, including slow response times and inconvenient operation.

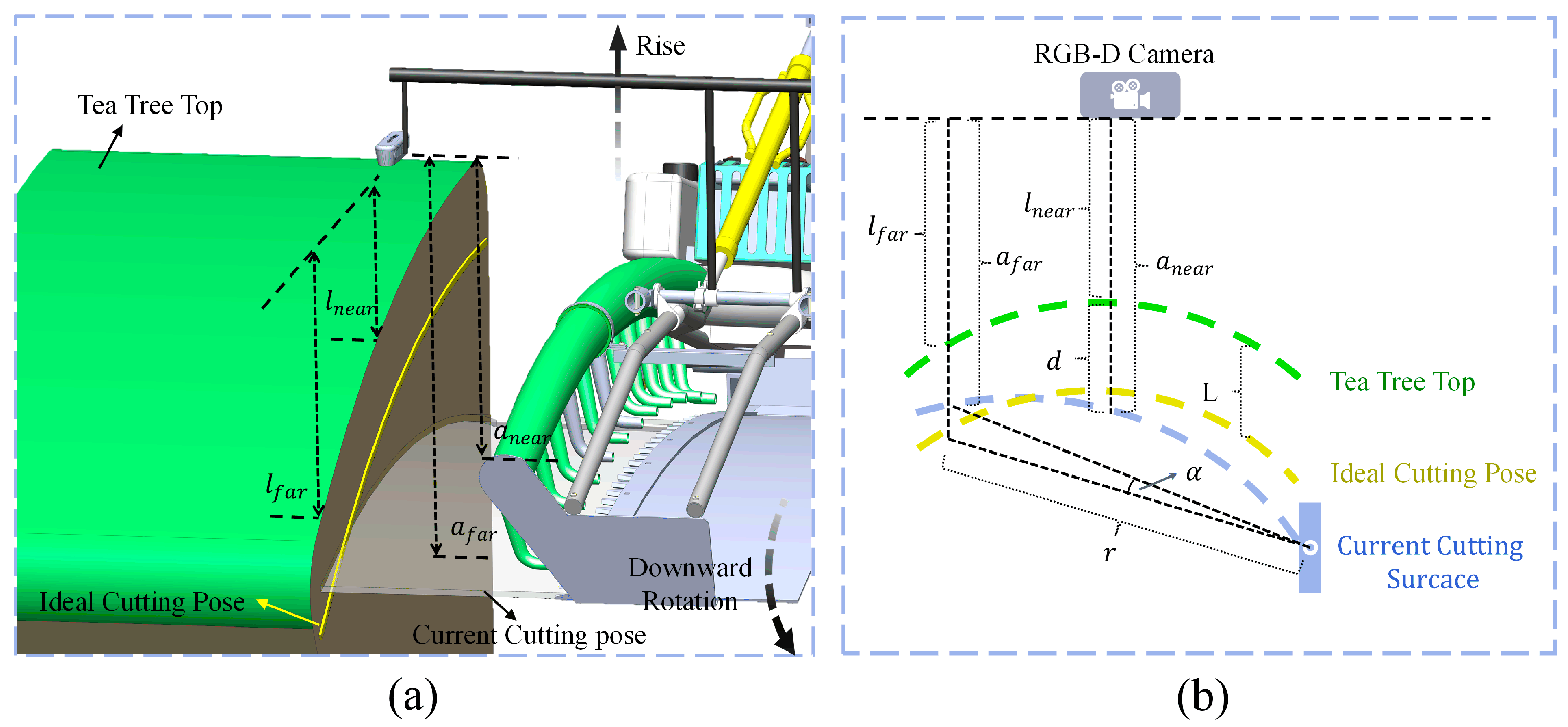

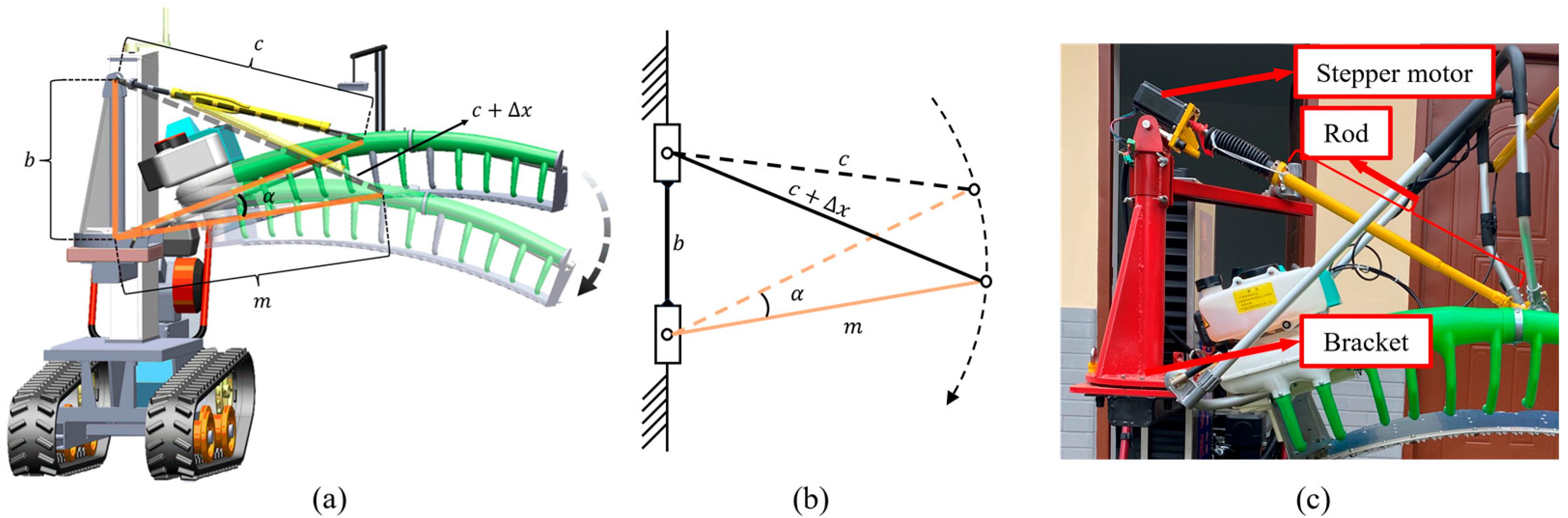

By achieving adaptive profiling of the tea canopy, the automation level of mechanized bulk tea plucking can be significantly enhanced. The adaptive profiling of the tea canopy means that the arc-shaped cutter can change the cutting pose by recording the change data of the contour of the tea tree top. The profiling process can be implemented through mechanical contact structure, non-contact sensor detection, and machine vision. Two steel sheets connected with the angle sensor on the tea canopy could obtain the angular displacement, combined with the PLC control motor to adjust the rising and falling of the cutter automatically [

13]. On the contrary, the change in contact force easily affected the mechanical contact structure. Tang et al. separated the tea shoots and the cutter through computer vision algorithms to detect the tea shoots’ pixel size to control the cutter’s height [

14]. However, the cutter adjustment position of this design solution was limited [

15]. Zhao et al. developed a distributed controlled riding tea plucking machine, which used an ultrasonic sensor to sense the distance between the tea canopy and the cutter [

16]. Screw rod transmission was used to realize the profiling of the tea canopy. Significantly, the highly precise non-contact sensor could not distinguish the tea shoots from the tea canopy, so the old leaves would influence the obtained data. Using an RGB-D camera to segment tea shoots and considering the depth of the tea shoots as the basis for height and angle adjustment of the cutter can avoid the disadvantages of the above methods.

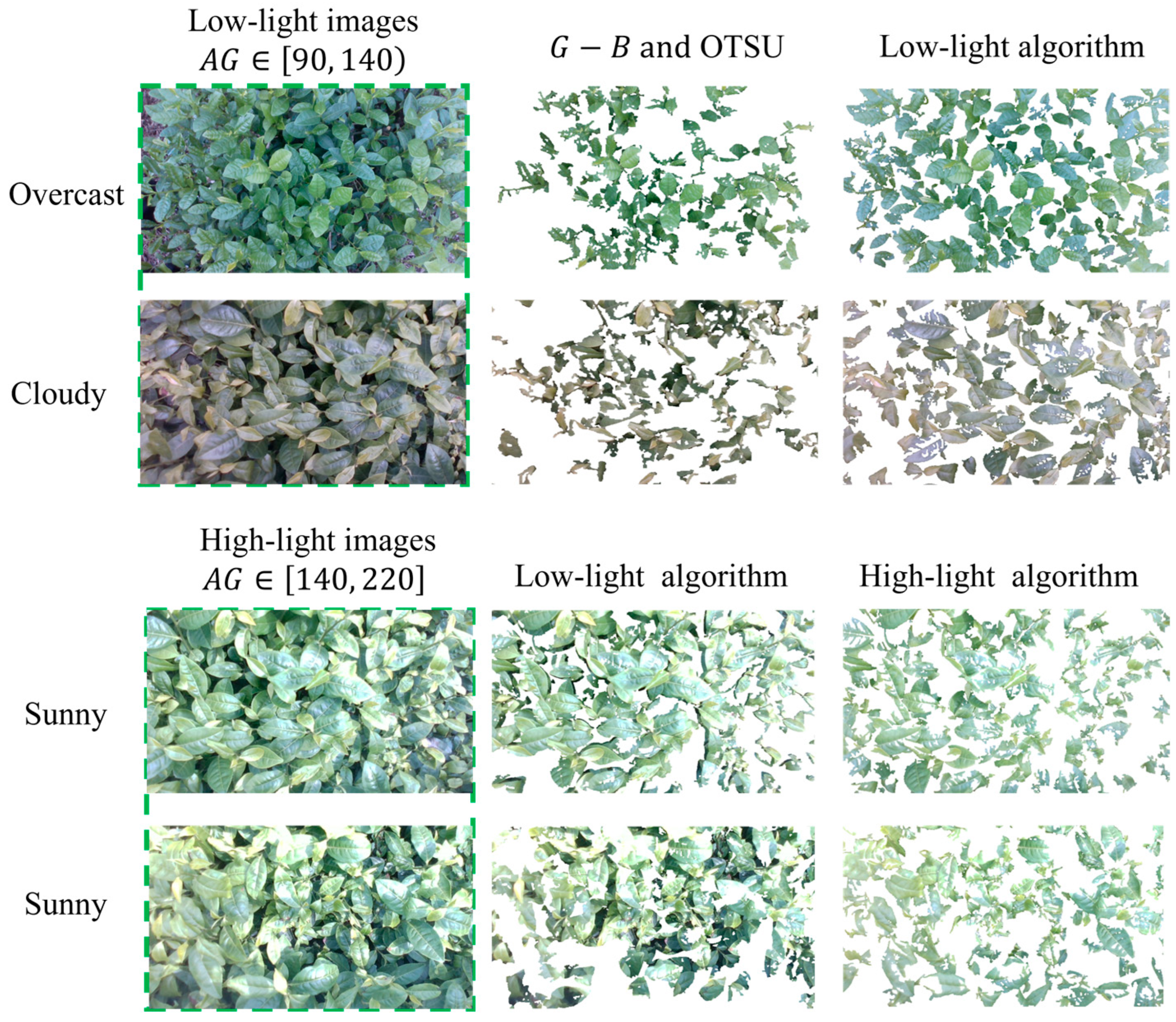

Tea shoot detection is an essential part of the tea plucking process. Color and shape features are often used to detect tea shoots traditionally. Tang et al. analyzed the thresholds of G and G-B components to distinguish tea shoots from the image by the improved Otsu algorithm [

14]. Wang et al. used an improved algorithm based on color and regional growth to divide the tea shoots in the images [

17]. According to the model database, the characteristic parameters of tea shoots were extracted to complete the three-dimensional modeling of tea shoots. Zhang et al. proposed a new tea shoot recognition and segmentation method based on an improved watershed algorithm, which used B and G-B components to improve the differentiation degree of old leaves and tea shoots [

7]. Qin et al. used the R-B components to identify the buds of the famous tea and used Otsu for threshold segmentation. The processing time was 0.288 s, and the average misidentification rate was 28.7% [

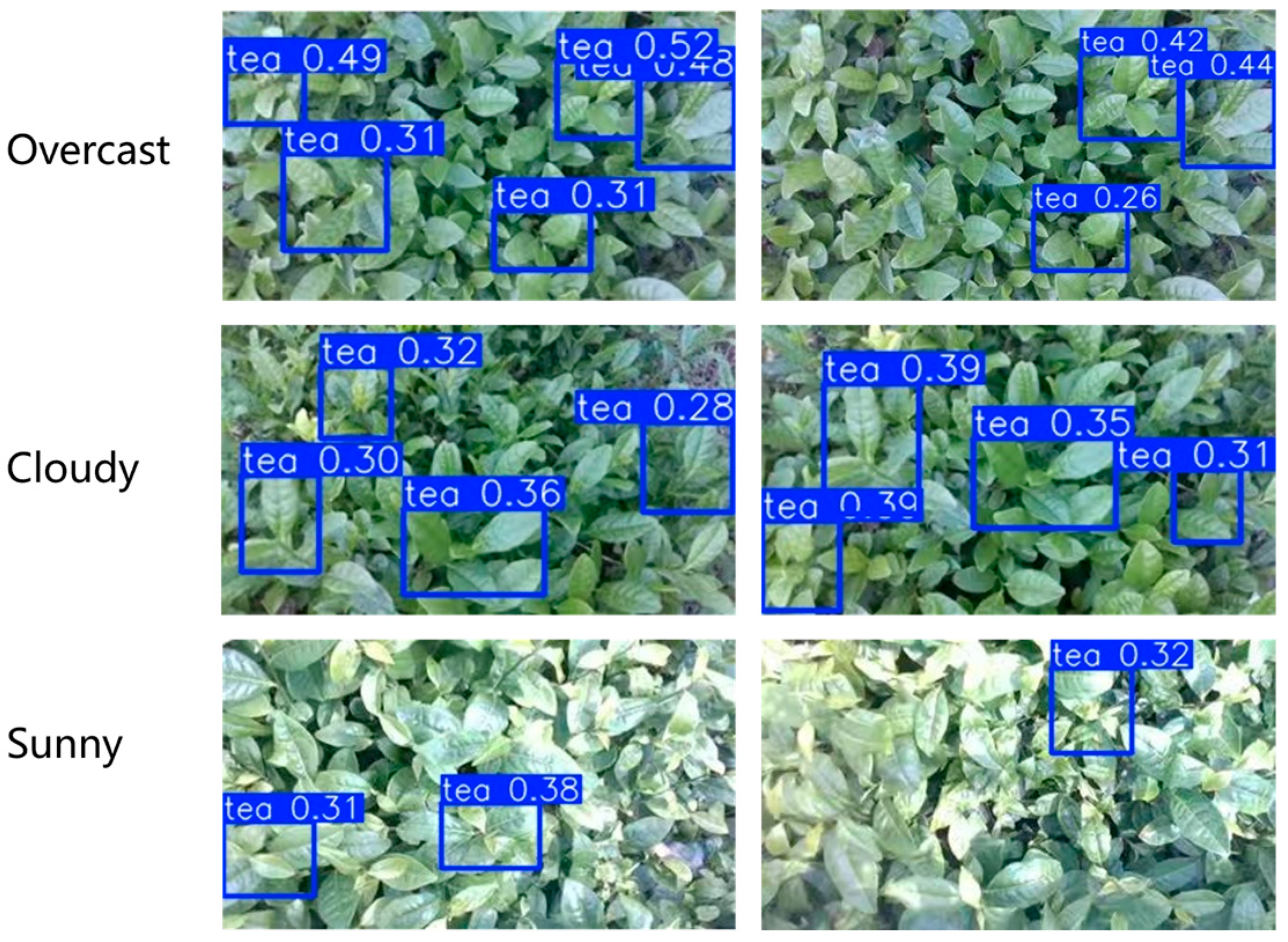

18]. Significantly, the differentiation between a single bud without leaves and a bud with one leaf could not be accomplished by color features alone. There also would be a certain degree of false recognition due to light effects. It can be seen that traditional detection methods based on color and shape features can be applied to recognize tea shoots with short processing time and certain recognition accuracy. Deep learning techniques have recently emerged as powerful methods for learning feature representations automatically from data, which have improved objection detection significantly [

19]. Ji et al. proposed an apple recognition method based on improved YOLOv4, which can locate and recognize apples in various complex environments [

20]. Xu et al. presented a detection and classification approach based on the YOLOv3 and DenseNet201 network, and the results showed that the recognition accuracy of tea shoots reached 95.7% for the images shot from the side [

21]. Gui et al. applied the Yolo-Tea object detection algorithm to tea bud detection and improved tea bud recognition in unstructured environments [

22]. Xie et al. proposed Tea-YOLOv8s for tea bud detection, integrating data augmentation, DCNv2, GAM attention and SPPFCSPC. It achieved 88.27% mAP@0.5, outperforming YOLOv8s by 3.59 percentage points in tea bud detection [

23]. Fang et al. developed lightweight TBF-YOLOv8n for tea bud detection, with DSCf, CA attention, SIOU loss and DySample. It reached 87.5% precision and 85.0% mAP50 for tea buds, reducing GFLOPs by 44.4% vs. YOLOv8n [

24]. It can be perceived that the deep learning method has better recognition accuracy and is the critical technology for famous tea plucking.

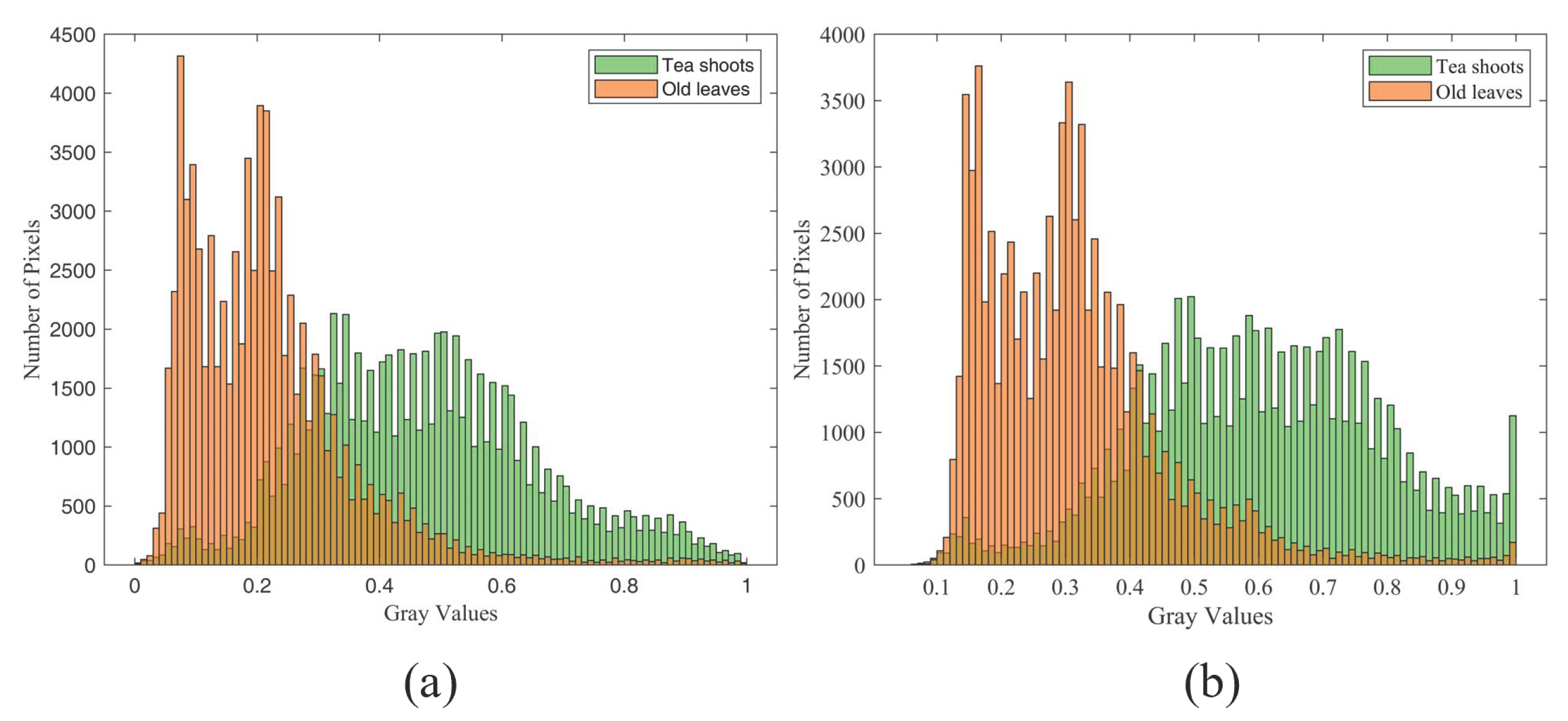

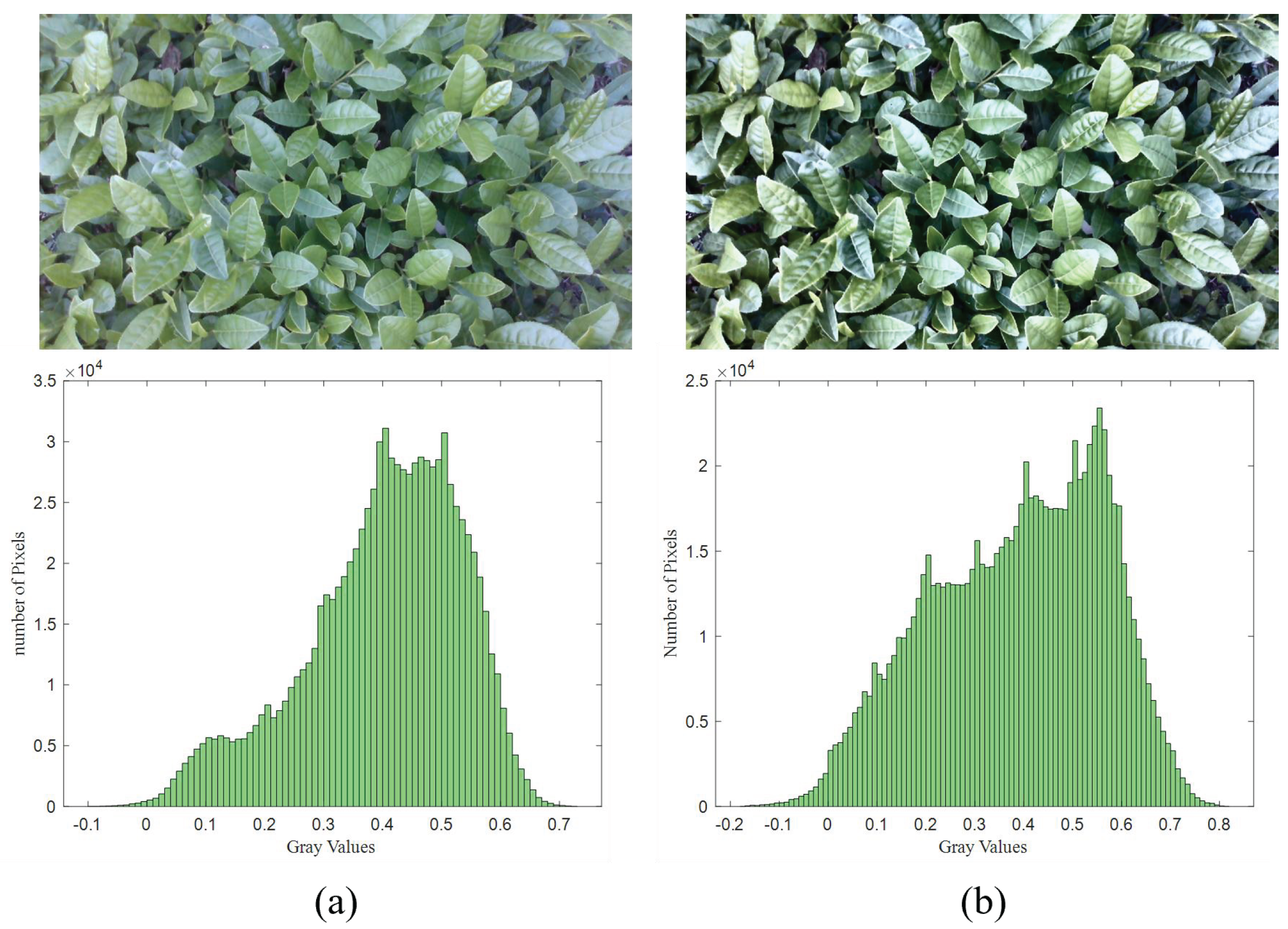

In summary, in the field of tea shoot detection, both traditional image processing methods and deep learning methods have been widely applied. However, famous tea and bulk tea exhibit distinct characteristics, as shown in

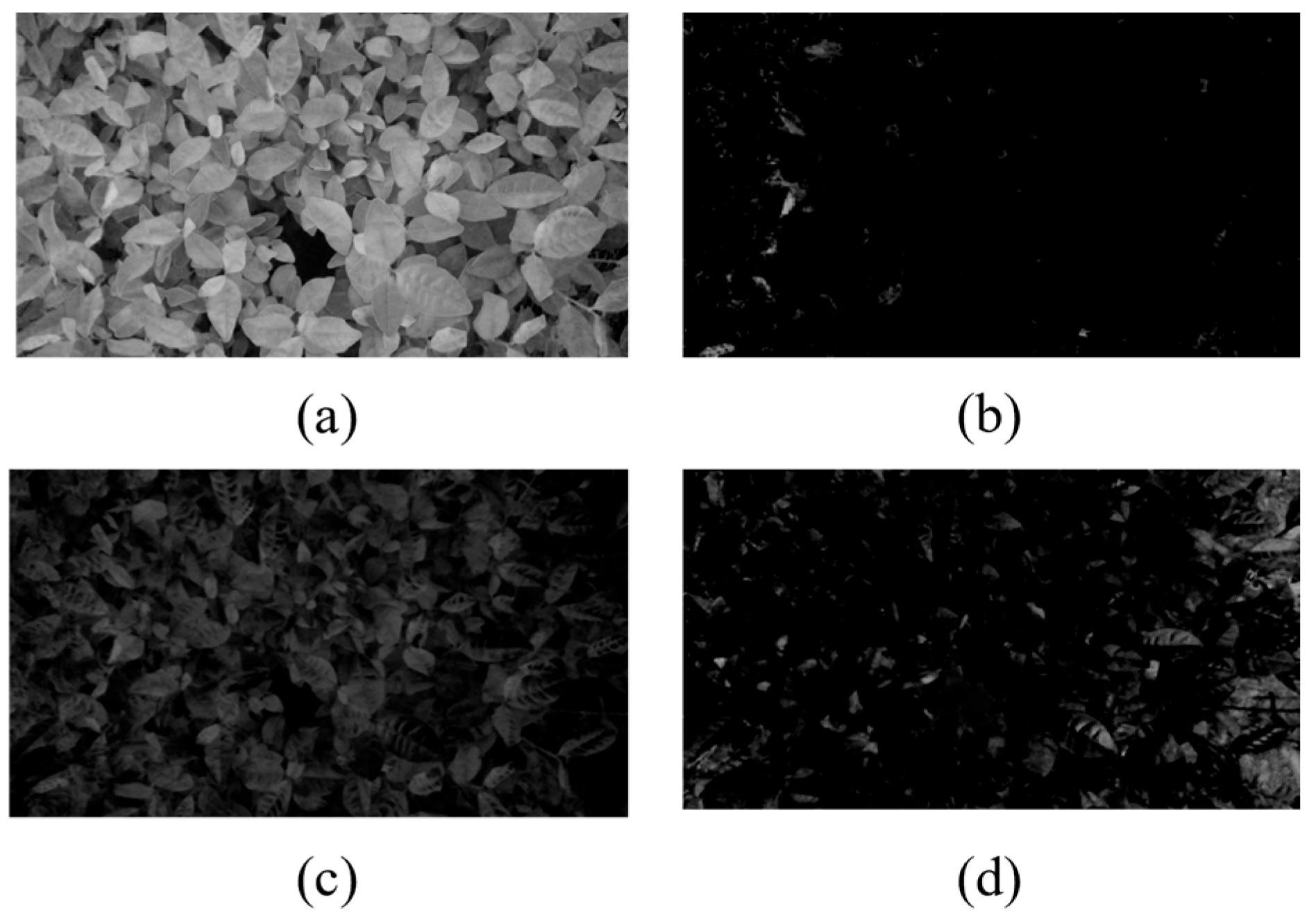

Figure 2. The famous tea shoots are scattered within the tea canopy and exhibit significant differences in both color and shape features compared to the older leaves. In contrast, the bulk tea shoots are distributed across the entire surface of the tea canopy, exhibiting significant color differences compared to the old leaves, while their shape characteristics are similar. If deep learning is used to detect bulk tea only based on color differences, there will be false detections and missed detections. In this study, image processing aims to acquire depth information of tea shoots and provide a basis for cutter profiling. Tea shoot detection can minimize the impact of depth values from old leaves and backgrounds, enhancing the accuracy of cutting pose calculation. Therefore, a bulk tea shoot detection algorithm under different weather conditions based on color features and threshold segmentation is developed to segment bulk tea shoots.

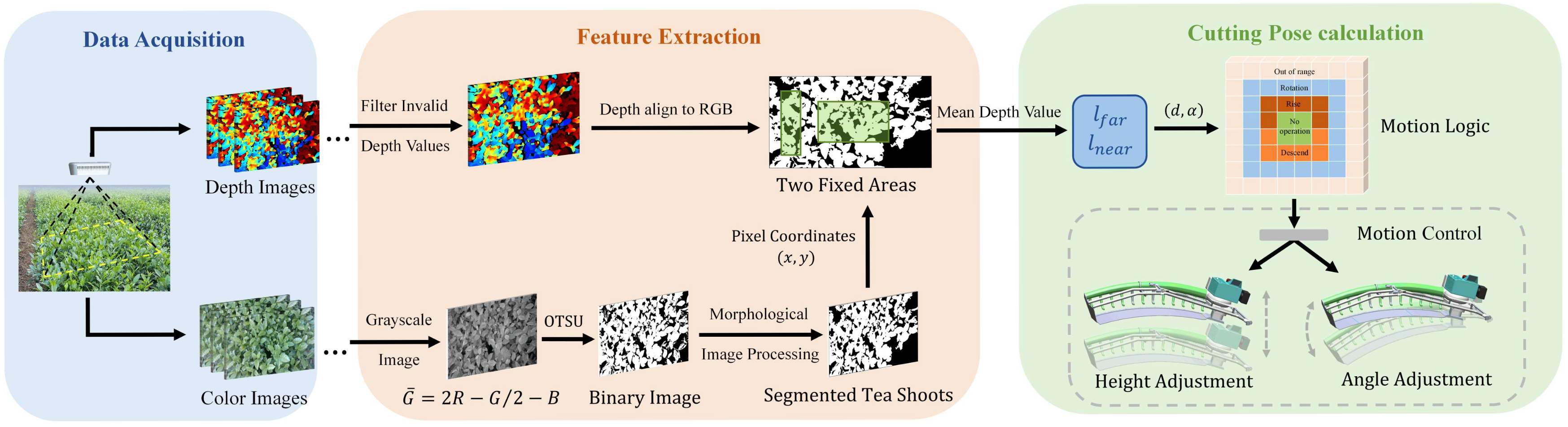

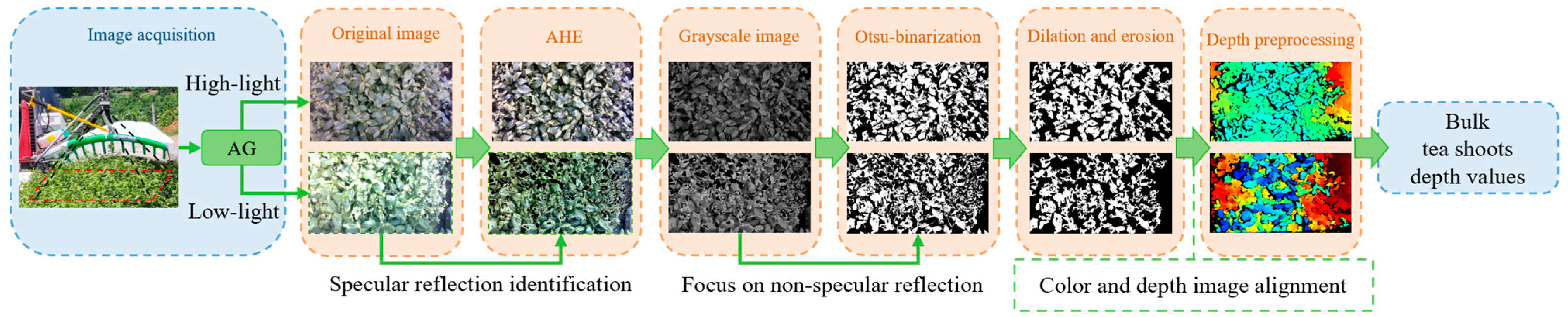

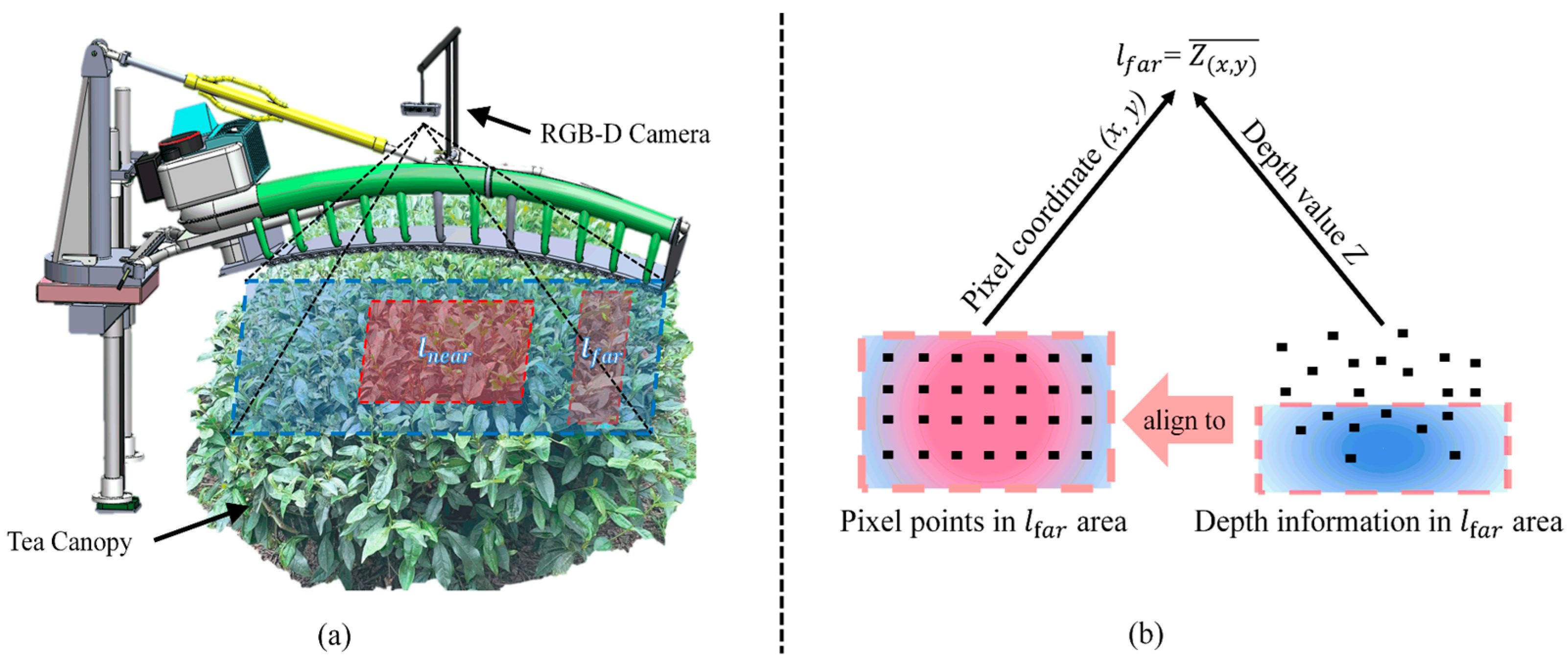

The study includes the following parts: (i) detection and segmentation of bulk tea shoots in RGB images captured by RGB-D cameras under different lighting conditions using improved super-green features and the Otsu method, and extraction of the valid depth information corresponding to the young shoot regions in the tea canopy based on the segmented images. (ii) A cutter profiling method is designed to define and calculate the cutting pose based on the depth information of the bulk tea shoots. (iii) A field test is conducted to verify the effectiveness of the designed tea plucking system.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the bulk tea shoot detection algorithm and details the cutter profiling method and control scheme. Experiment results and discussion are provided in

Section 3. Finally, conclusions are drawn in

Section 4.

4. Discussion

The main focus of this study is the cutter profiling method of the bulk tea plucking machine. However, it is also necessary to consider other aspects, including how agricultural machines can overcome the vibration effects. The vibration of the tea plucking machine mainly originates from three sources: the engine of the crawler chassis, the cutter’s engine, and the vibration produced during the reciprocating cutting process. In order to reduce mechanical vibrations, we will replace the gasoline engine with an electric drive in the future to reduce vibration levels. In addition, the vibration generated when cutting the tea canopy can not be eliminated entirely but can be improved by implementing measures such as adding rubber shock absorbers to the camera installation position. These measures can alleviate the vibration impact during tea plucking in hilly terrains, thereby ensuring the quality of RGB and Depth images and enhancing the stability and performance of the system.

Different lighting conditions for intelligent agricultural machines with outdoor work requirements cause an overall change in image brightness and a decrease in image contrast. We have proposed a suitable solution to address this issue in

Section 2.2. In addition, we can activate the camera’s automatic exposure function, increase the resolution, and define a specific region of interest (ROI) to mitigate the impact of lighting conditions on the algorithm. This approach helps mitigate the adverse effects of excessive brightness and reduced contrast caused by specular reflection, ensuring more reliable and accurate image analysis for the algorithm.

Moreover, the tea plucking machine with a cantilever structure, as opposed to the riding structure, provides better passability and adaptability in hilly terrains. The positioning adjustment mechanism is only required on one side of the cutter, while the riding tea plucking machine requires moving rails on both sides of the cutter. Additionally, the cantilever structure facilitates easy disassembly of the cutting blade and allows operators to observe the tea canopy and the actual cutting effect more conveniently. However, unlike the riding tea plucking machine, the cantilever structure cannot physically shield the sunlight.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that the qualification rate of buds and leaves is also influenced by tea plantation management. Non-standard curved planting of tea canopies can lead to chaotic growth of tea shoots, and satisfactory harvesting results cannot be obtained using a profiling tea plucking machine. The cutter profiling method of the tea plucking machine described in this study applies to tea plantations with standardized management and demonstrates a certain degree of universality. We are working with local agricultural departments to promote a standardized tea plantation management system to lay the foundation for future standardized management.

5. Conclusions

In order to improve the automation of bulk tea harvesting, we proposed an adaptive profiling method that included bulk tea shoot detection, cutter two-dimensional pose calculation and motion control. The experimental results show that the detection algorithm can improve the performance of cutter profiling. Each image of the tea canopy taken by the RGB-D camera will correspond to a certain motion logic, and then the height and angle of the cutter are adjusted to achieve the profiling purpose. Compared with the popular double-carried tea plucking machine, the study significantly improves plucking efficiency. Meanwhile, the field test results verified the profiling method’s performance, and the indicators, such as the rates of intact buds and leaves, met the operating quality standards of tea plucking machines.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) An improved super-green feature and the Otsu method were studied for identifying bulk tea shoots under different lighting conditions, so as to meet the requirements of target detection in field environments.

(2) In response to the requirement of automatically adjusting the cutting pose of the cutter, an adaptive profiling cutting strategy based on the depth information of young tea shoots was proposed.

(3) The design and implementation of the adaptive profiling tea harvester system were completed, and field validation was conducted in tea plantations in hilly areas, demonstrating the efficiency and feasibility of the system.

Although there are still some aspects and room to be improved continuously in architecture, this study provides a new idea for the profiling method of bulk tea plucking machines, which greatly alleviates the crisis caused by the shortage of rural labor in tea production. To improve the profiling accuracy in future work, it is necessary to dynamically adjust the areas of two fixed regions according to the cutting area of the cutter.