A Solar Array Temperature Multivariate Trend Forecasting Method Based on the CA-PatchTST Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A patch-based, channel-independent PatchTST encoder further enhances local pattern extraction, lowers computational cost, and preserves long-range temporal patterns;

- Cross-attention across devices captures inter-variable correlations and enables complementary information exchange among multivariate telemetry channels;

- Extensive experiments on real-world GOCE satellite temperature telemetry data validate CA-PatchTST across multiple forecast horizons. The results show consistent and significant improvements over state-of-the-art baselines, with superior performance in RMSE, MAE, and MAPE, underscoring the model’s accuracy, robustness, and practical utility.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Time-Series Trend Forecasting Methods

2.2. Time-Series Trend Forecasting Methods Based on Deep Learning

2.3. Transformer

3. Methodology

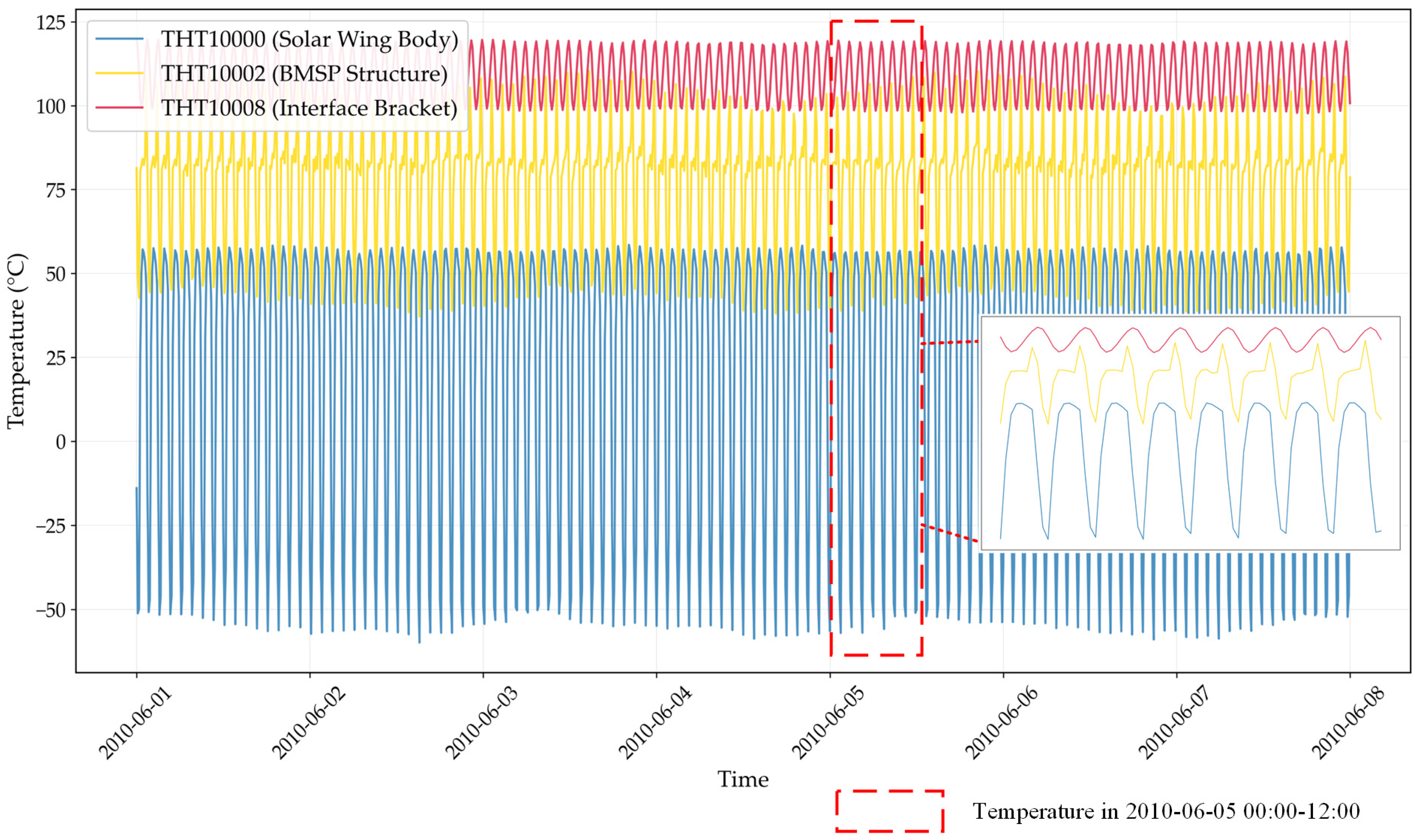

3.1. Solar Array Temperature Telemetry Data

3.2. CA-PatchTST

3.2.1. Temperature Series Decomposition

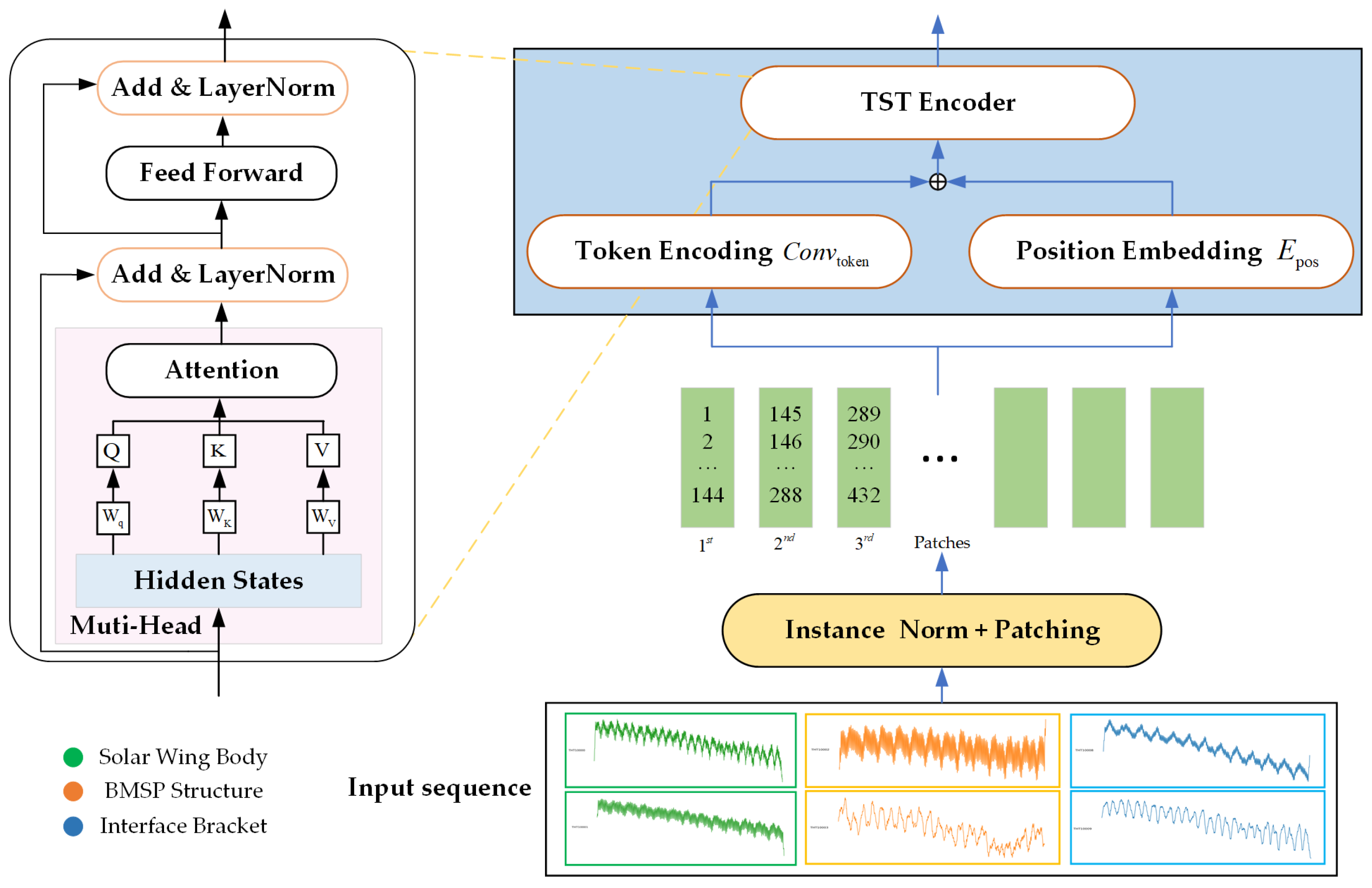

3.2.2. PatchTST

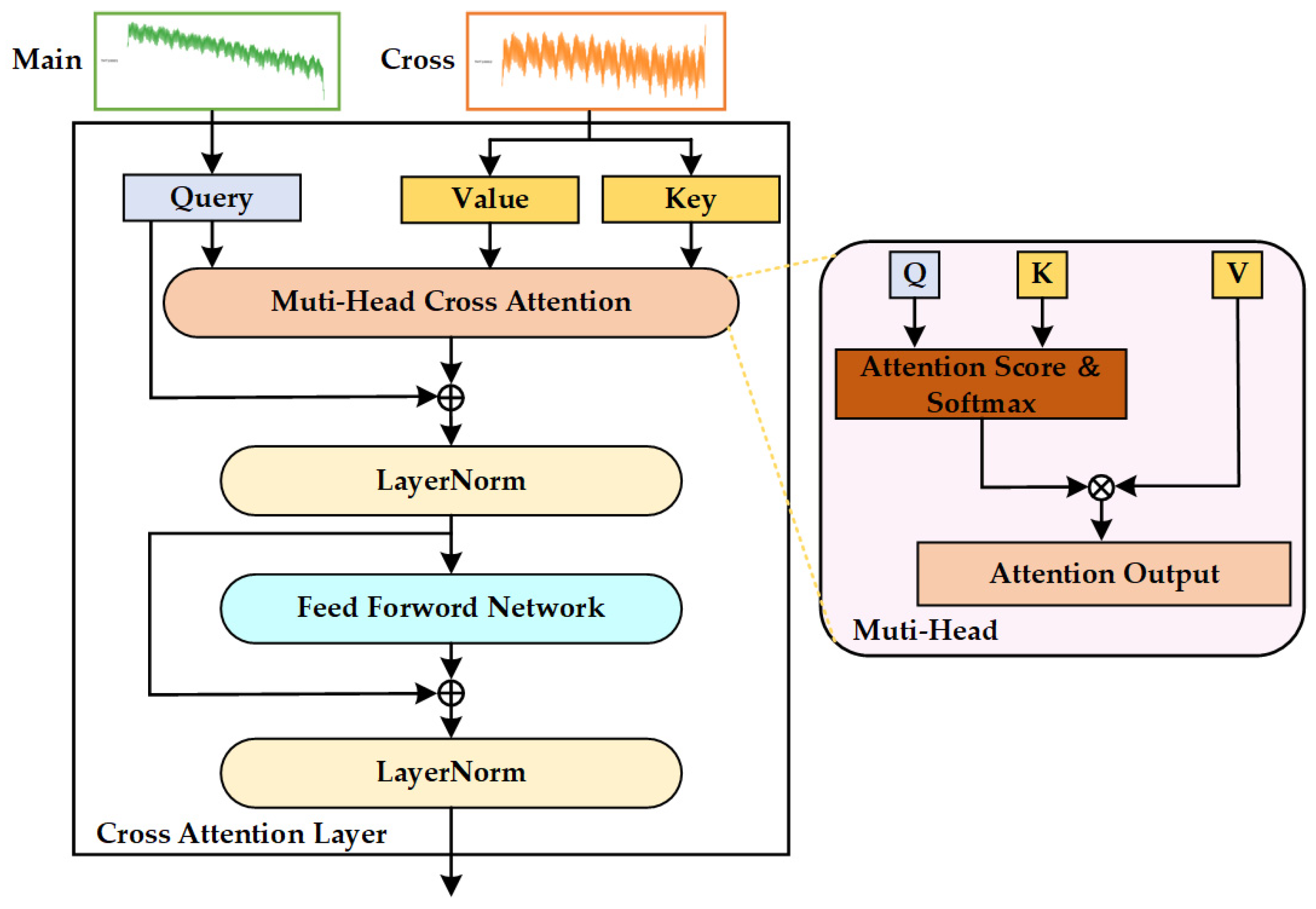

3.2.3. Cross-Attention Mechanism

3.2.4. Output Fusion

3.2.5. Model Architecture

3.2.6. Implementation Procedure of CA-PatchTST

| Algorithm 1. CA-PatchTST for Solar Array Temperature Trend Forecasting |

| 1: Input: Multivariate temperature sequence: , Device partition: , patch length , stride , forecast horizon |

| 2: Organize sequences by device groups: 3: for component do: 4: Apply moving average filtering: 5: Compute residual component: 6: end for 7: for component do: 8: for branch do: 9: Patching: 10: Linear Projection & Position Encoding: 11: Channel-independent TST Encoding: 12: end for 13: end for 14: for component do: 15: Extract representations: 16: Multi-head Cross-Attention: , 17: Residual Connection & Layer Normalization: 18: Feed-Forward Network: 19: end for |

| 20: for component do: 21: Flatten and project to forecast horizon: 22: end for 23: Additive Fusion: |

| 24: Compute MSE loss: 25: Update parameters: 26: Output: Multi-step forecasts |

4. Experiments

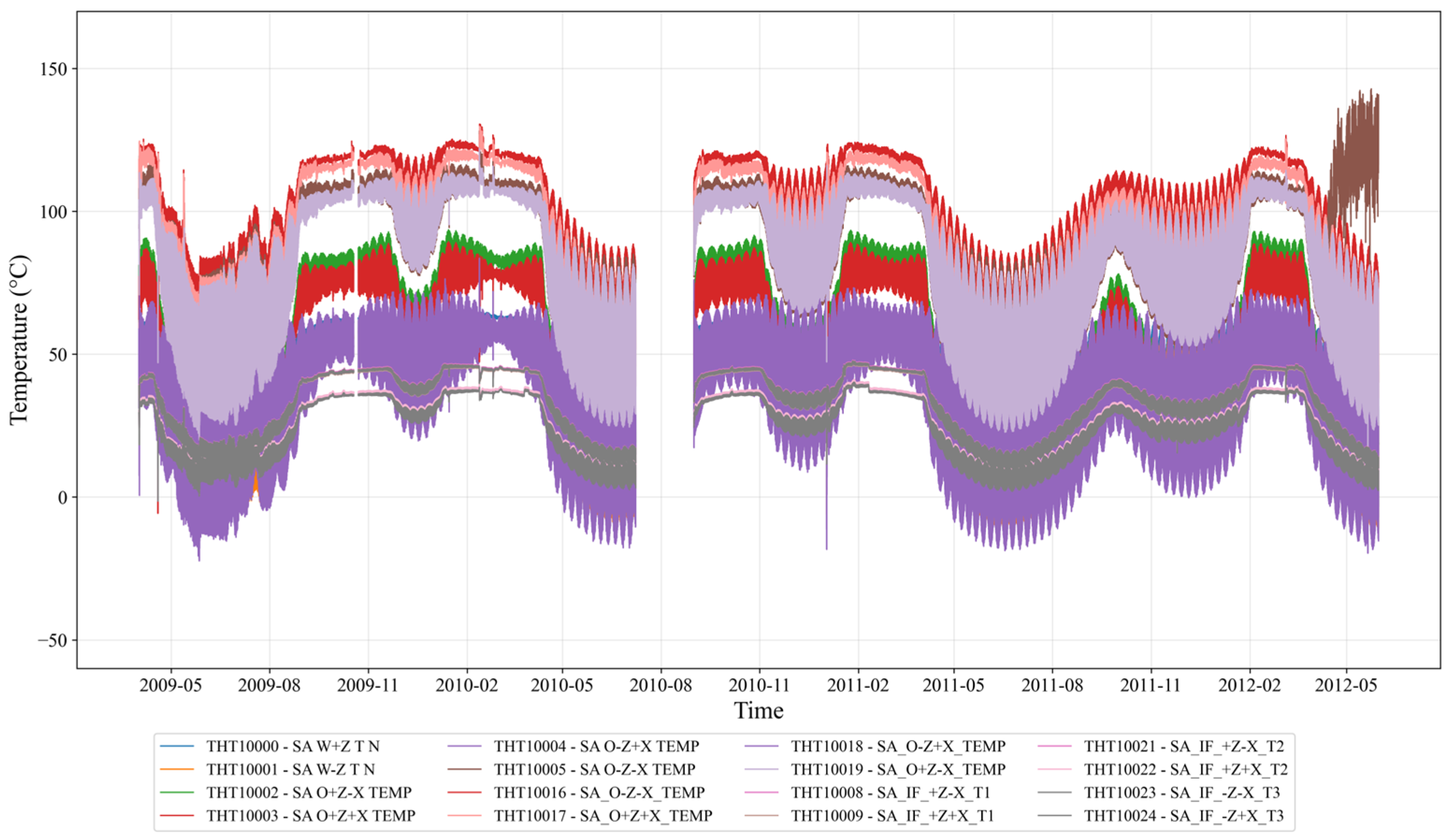

4.1. GOCE Satellite Temperature Dataset

4.2. Experiment Settings

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

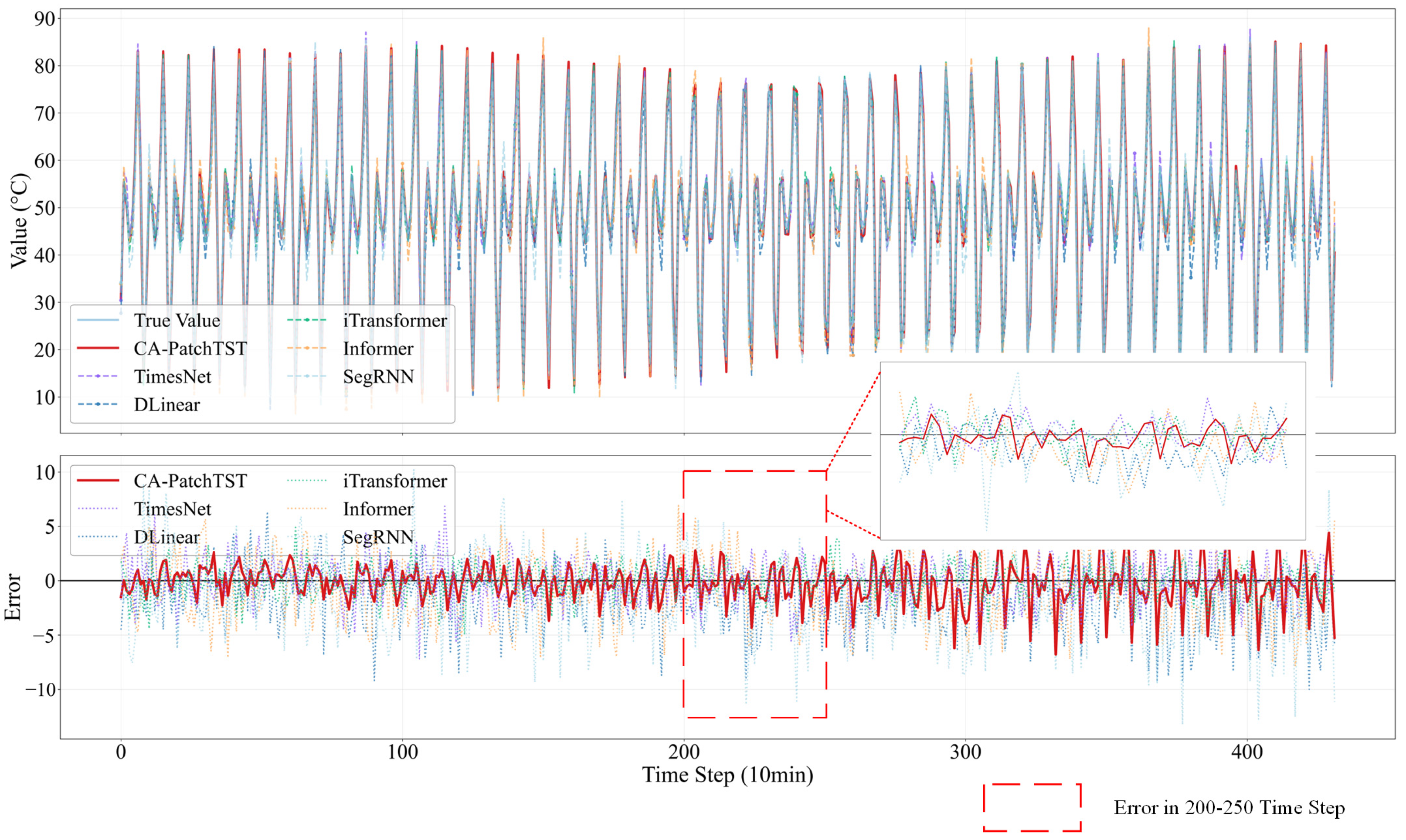

4.4. Comparison with Other Methods

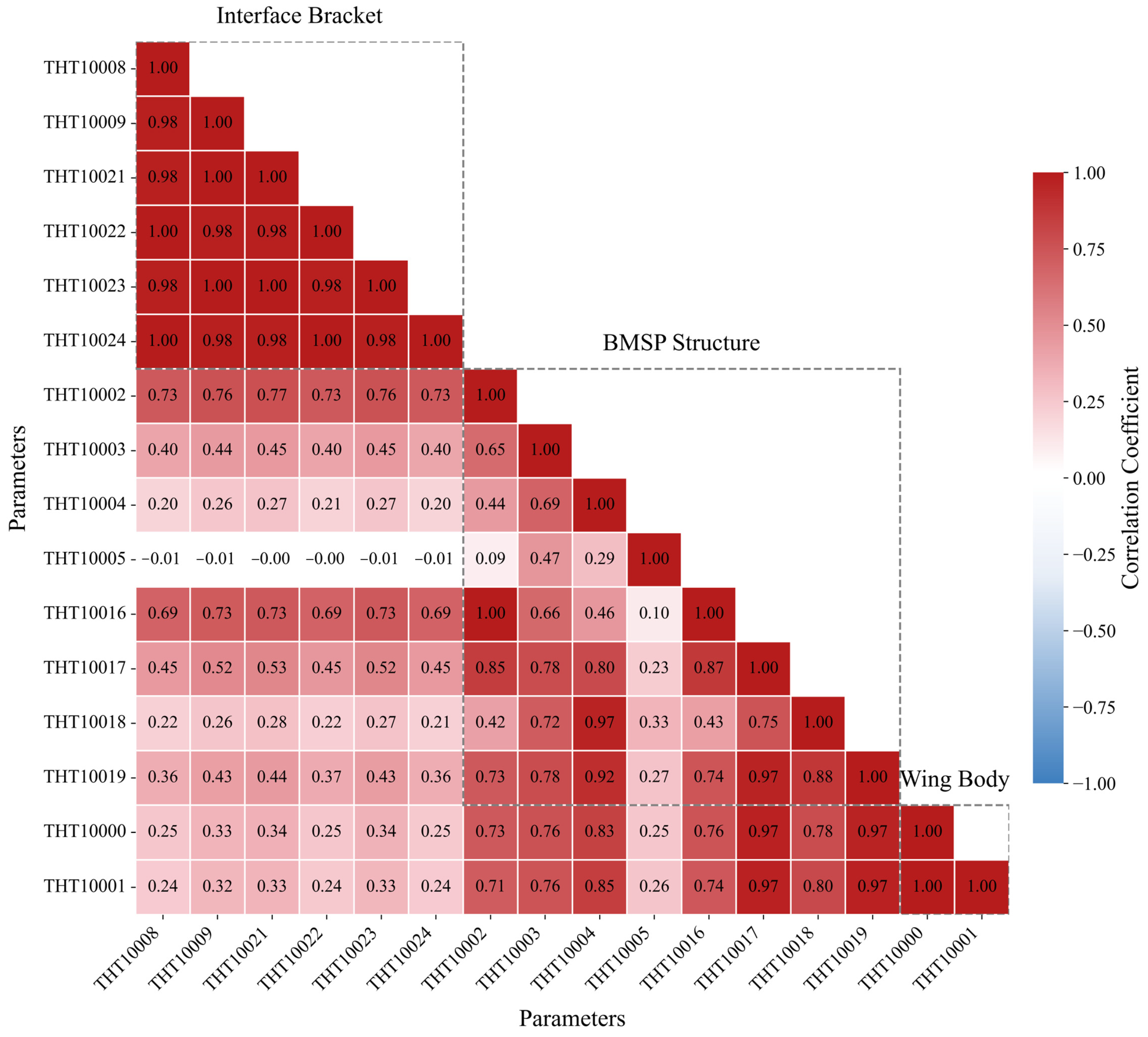

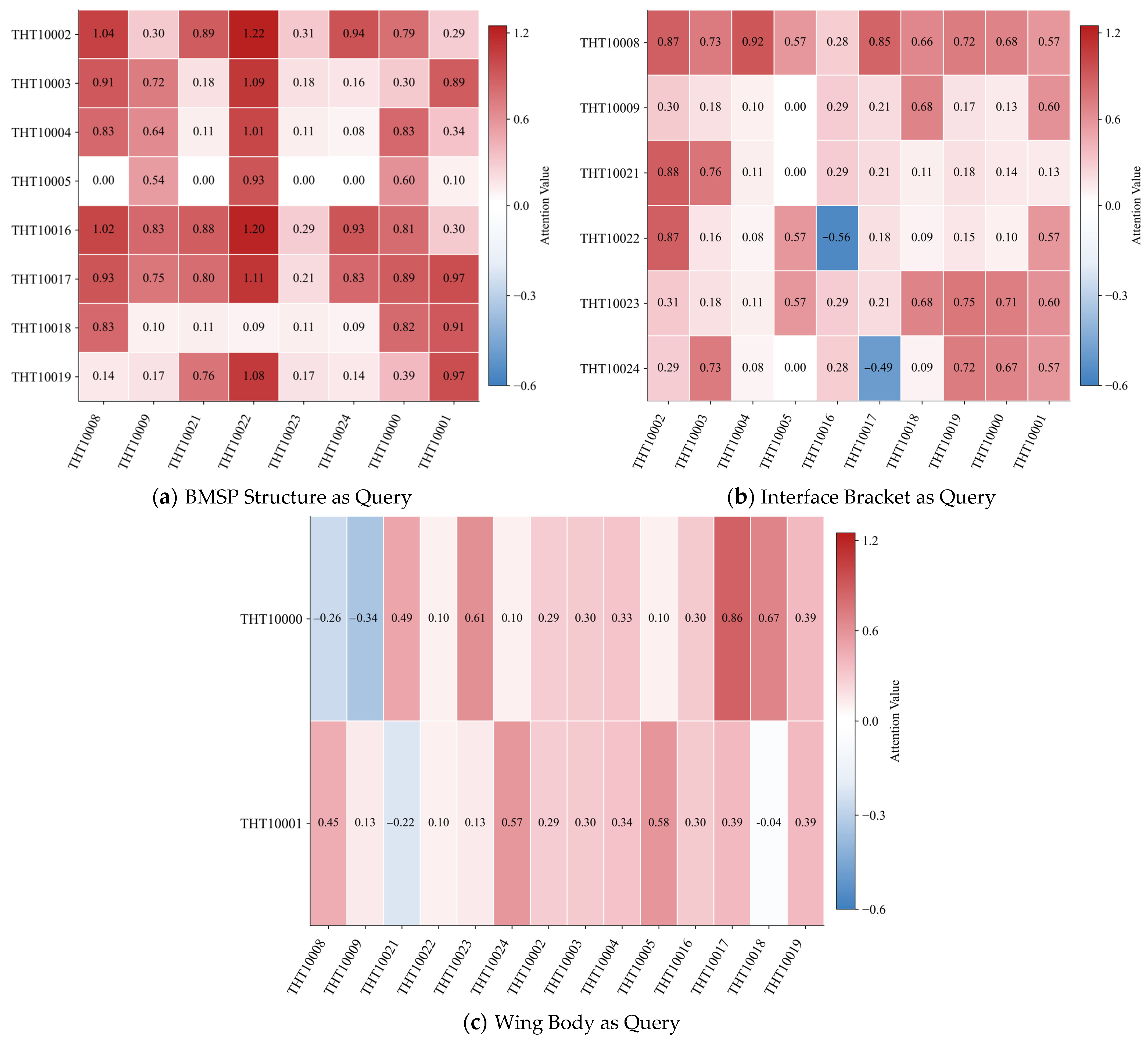

4.4.1. Attention Visualization

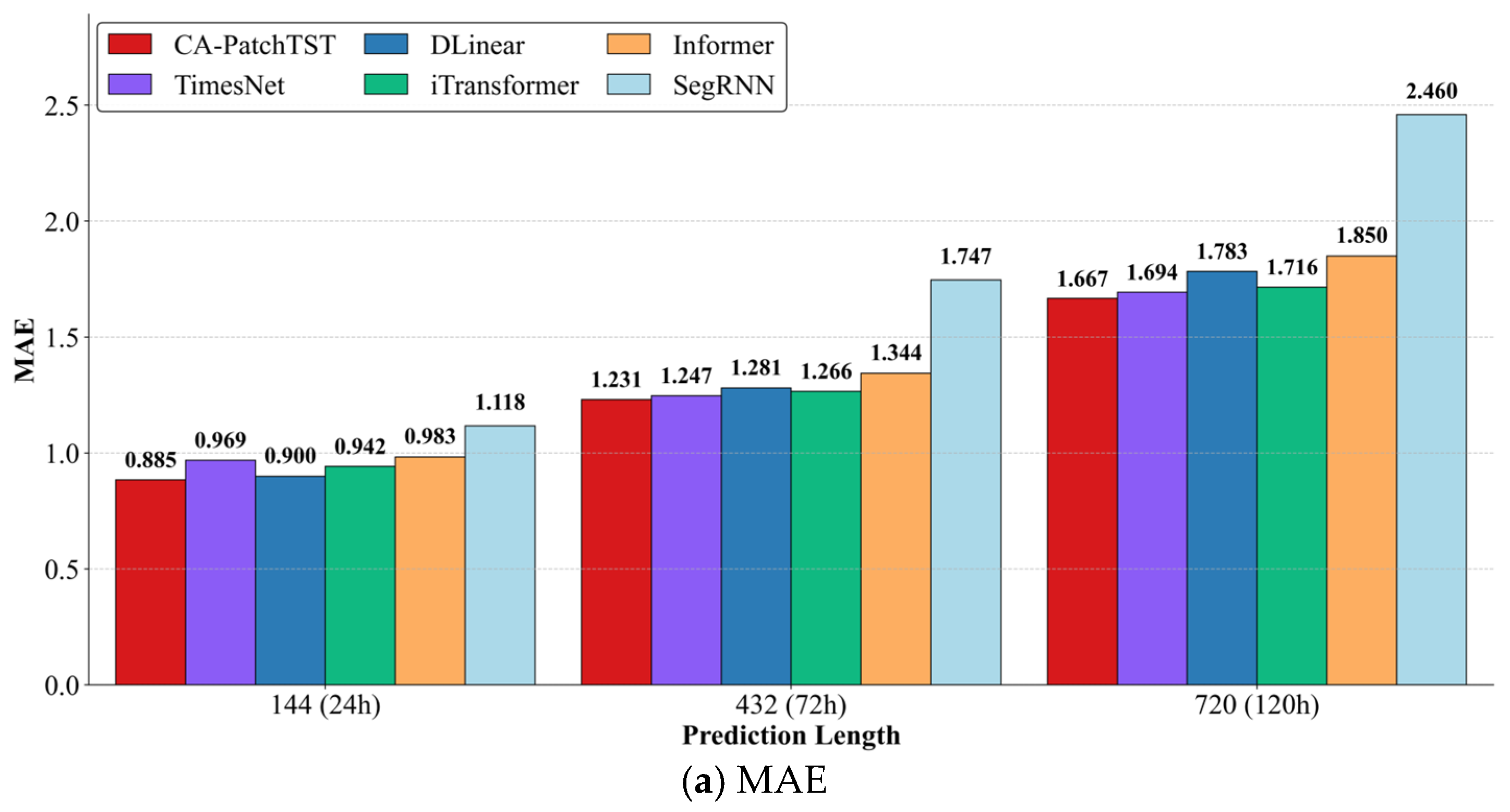

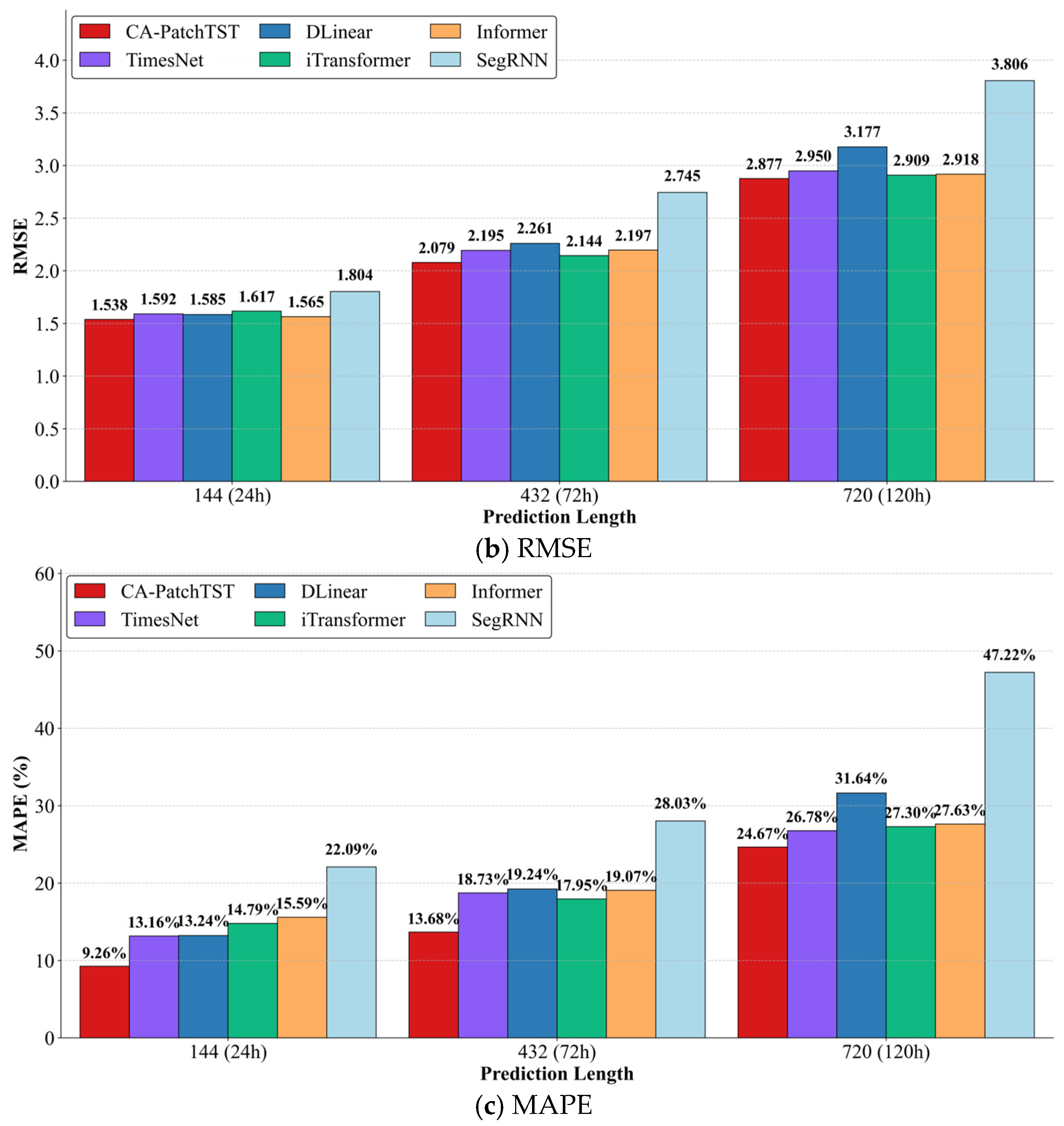

4.4.2. Comparison with Other Forecasting Methods

4.5. Ablation Experiment

4.5.1. Component Ablation Experiment

4.5.2. Backbone-Attention Ablation Experiment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CA-PatchTST | Cross-Attention Patch Time-Series Transformer |

| PCC | Pearson correlation coefficient |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| FFN | Feed-Forward Network |

| GOCE | Gravity field and steady-state Ocean Circulation Explorer |

| SE | Squeeze-and-Excitation |

| SRU | Simple Recurrent Unit |

| TCN | Temporal Convolutional Network |

References

- Nwankwo, V.U.; Jibiri, N.N.; Kio, M.T. The impact of space radiation environment on satellites operation in near-Earth space. In Satellites Missions and Technologies for Geosciences; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Sun, Q.; Meng, J.; Pan, Z.; Tang, Y. Degradation modeling of satellite thermal control coatings in a low earth orbit environment. Sol. Energy 2016, 139, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafazoli, M. A study of on-orbit spacecraft failures. Acta Astronaut. 2009, 64, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, G.A.; Bailey, S.G.; Tischler, R. Causes of power-related satellite failures. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE 4th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conference, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 7–12 May 2006; pp. 1943–1945. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.K.; Banks, B. Degradation of spacecraft materials in the space environment. MRS Bull. 2010, 35, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Andrada, R.; Borja, D. A framework of big data driven remaining useful lifetime prediction of on-orbit satellite. In Proceedings of the 2021 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), Orlando, FL, USA, 24–27 May 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ochuba, N.; Usman, F.; Okafor, E.; Akinrinola, O.; Amoo, O. Predictive analytics in the maintenance and reliability of satellite telecommunications infrastructure: A conceptual review of strategies and technological advancements. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Cheng, Z.; Guo, B. Anomaly detection in satellite telemetry data using a sparse feature-based method. Sensors 2022, 22, 6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Kong, C.; Shen, Y.; Lin, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. Short-Period Characteristics Analysis of On-Orbit Solar Arrays. Aerospace 2025, 12, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Guo, B. A hybrid data-driven framework for satellite telemetry data anomaly detection. Acta Astronaut. 2023, 205, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, Y.; Chang, X.; Fujita, H.; Wu, J. An attention-based deep learning model for multi-horizon time series forecasting by considering periodic characteristic. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 185, 109667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Jia, S.; Xie, L.; Shang, J. Accurate Satellite Operation Predictions Using Attention-BiLSTM Model with Telemetry Correlation. Aerospace 2024, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, X.; Xiong, H.; Tang, J.; Su, J.; Jin, B.; Dou, D. Towards long-term time-series forecasting: Feature, pattern, and distribution. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 39th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Anaheim, CA, USA, 3–7 April 2023; pp. 1611–1624. [Google Scholar]

- Haupt, S.E.; McCandless, T.C.; Dettling, S.; Alessandrini, S.; Lee, J.A.; Linden, S.; Petzke, W.; Brummet, T.; Nguyen, N.; Kosović, B. Combining artificial intelligence with physics-based methods for probabilistic renewable energy forecasting. Energies 2020, 13, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, R.; Kulikov, I. Forecasting Spacecraft Telemetry Using Modified Physical Predictions. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the PHM Society, Portland, OR, USA, 10–14 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Han, S.; Ye, J.; Hao, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Jia, K. A method for precisely predicting satellite clock bias based on robust fitting of ARMA models. GPS Solut. 2022, 26, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Rong, F. Prophet–CEEMDAN–ARBiLSTM-Based Model for Short-Term Load Forecasting. Future Internet 2024, 16, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Si, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Li, P.; Feng, Y. Industrial Internet intrusion detection based on Res-CNN-SRU. Electronics 2023, 12, 3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Lin, W.; Wu, W.; Zhao, F.; Mo, R.; Zhang, H. Segrnn: Segment recurrent neural network for long-term time series forecasting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.11200. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Shi, L.; Wang, R. Remaining useful life prediction based on adaptive SHRINKAGE processing and temporal convolutional network. Sensors 2022, 22, 9088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting? In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; pp. 11121–11128. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Ma, Z.; Yan, J.; Sun, L. Transformers in time series: A survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.07125. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, J.M.; Ramos, P. Evaluating the effectiveness of time series transformers for demand forecasting in retail. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar, S.; Santos, M.; Alonso, F.; Fabregas, E.; Farias, G. Explainable anomaly detection in spacecraft telemetry. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, N.; Tian, J. Time series forecasting of motor bearing vibration based on informer. Sensors 2022, 22, 5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Gao, X.; Ding, T.; Li, F.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, R. A hybrid deep learning model for short-term load forecasting of distribution networks integrating the channel attention mechanism. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 1770–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, J. Crossformer: Transformer utilizing cross-dimension dependency for multivariate time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Keles, F.D.; Wijewardena, P.M.; Hegde, C. On the computational complexity of self-attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithmic Learning Theory, Singapore, 20–23 February 2023; pp. 597–619. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer, M.; Guruganesh, G.; Dubey, K.A.; Ainslie, J.; Alberti, C.; Ontanon, S.; Pham, P.; Ravula, A.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L. Big bird: Transformers for longer sequences. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 17283–17297. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, H.; Jin, D.; Jia, M. Solar-Array Attenuation Analysis Method for Solar Synchronous Orbit Satellites. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Reliability, Maintainability and Safety (ICRMS), Urumuqi, China, 26–29 August 2023; pp. 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszczak, B.; Kotowski, K.; Evans, D.; Nalepa, J. The OPS-SAT benchmark for detecting anomalies in satellite telemetry. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, T.; Zdravkovic, J.; Papapetrou, P. Unpacking the trend: Decomposition as a catalyst to enhance time series forecasting models. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 39, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, Q.; Caron, G.M.; Aloise, D. A practical survey on faster and lighter transformers. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Jadon, A.; Patil, A.; Jadon, S. A comprehensive survey of regression-based loss functions for time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Management, Analytics & Innovation, Vellore, India, 19–21 January 2024; pp. 117–147. [Google Scholar]

- Rummel, R.; Gruber, T.; Flury, J.; Schlicht, A. ESA’s gravity field and steady-state ocean circulation explorer GOCE. ZFV-Z. Geodäsie Geoinf. Landmanag. 2009, 24, 339–386. [Google Scholar]

- RM, S. Computation of eclipse time for low-earth orbiting small satellites. Int. J. Aviat. Aeronaut. Aerosp. 2019, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, S.; Cai, R. Thermal analysis of composite solar array subjected to space heat flux. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2013, 27, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Timesnet: Temporal 2d-variation modeling for general time series analysis. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.02186. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Long, M. itransformer: Inverted transformers are effective for time series forecasting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06625. [Google Scholar]

| Block | Layer | Operation | Input Shape | Output Shape |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decomposition | Input | Main sequence, Cross sequence | [B, N, seq_len] | [B, , seq_len] [B, , seq_len] |

| Moving-average decomposition | Split each sequence into trend and residual component via MA filter | [B, , seq_len] [B, , seq_len] | [B, , seq_len] × 2 [B, , seq_len] × 2 (Trend/Res.) | |

| PatchTST (Single-Branch) | Patching | ReplicationPad1d | [B, , seq_len] | [B, , M, P] |

| Unfold and Permute | ||||

| Patch projection + Pos encoding | Linear projection | [B, , M, P] | [B, , M, D] | |

| Dropout | ||||

| Add learnable positional encodings | ||||

| TST Encoder × N (Channel-independent for per variable). | Multi-Head Self-Attention | [B, , M, D] | [B, , M, D] | |

| Dropout | ||||

| Residual shortcut | ||||

| LayerNorm | ||||

| FFN: Linear (D → 2D) → GELU → Dropout → Linear (2D → D) | ||||

| Residual shortcut | ||||

| LayerNorm | ||||

| Cross-Attention (Single-Branch) | Pre-CA | Q from main, K/V from cross | [B, , M, D] [B, , M, D] | Q: [B, , M, D] K/V: [B, , M, D] |

| Cross-Attention block × M | Multi-Head Cross-Attention: Reshape to muti-heads → Attn softmax → Dropout → Attn·V → Concat heads | [B, , M, D] [B, , M, D] | [B, , M, D] | |

| Dropout | ||||

| Residual shortcut | ||||

| LayerNorm | ||||

| FFN: Linear (D → 4D) → GELU → Dropout → Linear (4D → D) | ||||

| Residual shortcut | ||||

| LayerNorm | ||||

| Output and Fusion | Prediction head (Per branch) | Permute | [B, , M, D] | [B, , pred_len] |

| Flatten | ||||

| Linear projection | ||||

| Dropout | ||||

| Fusion (Trend + Residual) | Element-wise sum of branch outputs to obtain normalized prediction | [B, , pred_len] | [B, , pred_len] |

| Model Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| batch_size | 32 |

| epoch | 30 |

| learning_rate | 0.0001 |

| dropout | 0.05 |

| seq_len | 144 |

| patch_len | 16 |

| patch_stride | 8 |

| Encoder_layer_num | 2 |

| Linear_projection_size | 64 |

| Att_head_num | 4 |

| CA_layer_num | 2 |

| FFN_hidden_size | 128 |

| Models | Params (M) | Inference Time (ms) | Peak Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA-PatchTST | 4.9 | 10.5 | 2.4 |

| DLinear | 3.2 | 7.8 | 1.6 |

| TimesNet | 7.6 | 16.8 | 4.3 |

| iTransformer | 7.4 | 14.0 | 3.9 |

| Informer | 5.8 | 13.3 | 3.3 |

| SegRNN | 8.7 | 18.2 | 4.8 |

| Ablation | Forecasting Length | Metric | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | Decomposition | RMSE | MAE | MAPE | |

| √ | √ | 144 (24 h) | 1.538 | 0.885 | 9.26% |

| 432 (72 h) | 2.079 | 1.231 | 13.68% | ||

| 720 (120 h) | 2.877 | 1.667 | 24.67% | ||

| × | √ | 144 (24 h) | 1.710 | 1.040 | 16.35% |

| 432 (72 h) | 2.455 | 1.467 | 22.72% | ||

| 720 (120 h) | 3.003 | 1.764 | 27.61% | ||

| √ | × | 144 (24 h) | 1.545 | 0.892 | 12.52% |

| 432 (72 h) | 2.199 | 1.321 | 19.54% | ||

| 720 (120 h) | 2.969 | 1.729 | 28.05% | ||

| × | × | 144 (24 h) | 1.686 | 1.013 | 14.39% |

| 432 (72 h) | 2.220 | 1.350 | 16.68% | ||

| 720 (120 h) | 2.951 | 1.760 | 28.13% | ||

| Encoder Structure | Attention Mechanism | Metric | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | MAPE | ||

| PatchTST | CA | 2.079 | 1.231 | 13.68% |

| SE | 2.884 | 1.961 | 22.76% | |

| TCN | CA | 3.441 | 1.819 | 27.65% |

| SE | 3.999 | 2.015 | 29.34% | |

| SRU | CA | 3.385 | 1.803 | 18.69% |

| SE | 4.066 | 2.431 | 37.04% | |

| iTransformer | CA | 3.265 | 1.596 | 20.56% |

| SE | 3.990 | 1.900 | 34.27% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, F. A Solar Array Temperature Multivariate Trend Forecasting Method Based on the CA-PatchTST Model. Sensors 2025, 25, 7199. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237199

Wang Y, Shi X, Zhang Z, Zhou F. A Solar Array Temperature Multivariate Trend Forecasting Method Based on the CA-PatchTST Model. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7199. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237199

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yunhai, Xiaoran Shi, Zhenxi Zhang, and Feng Zhou. 2025. "A Solar Array Temperature Multivariate Trend Forecasting Method Based on the CA-PatchTST Model" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7199. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237199

APA StyleWang, Y., Shi, X., Zhang, Z., & Zhou, F. (2025). A Solar Array Temperature Multivariate Trend Forecasting Method Based on the CA-PatchTST Model. Sensors, 25(23), 7199. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237199