Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for ICVs in Vehicular Edge Computing Networks Based on Hybrid Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A vehicle–road collaborative edge computing network is proposed for efficient task offloading, where tasks from ICVs can be processed locally or offloaded to MEC for collaborative processing. The task offloading scheduling and resource allocation (TOSRA) optimization problem is formulated to effectively minimize the overall time and energy consumption costs of the dynamic system.

- To address the problem, TOSRA is decomposed into two-layer subproblems, and an HHDRL algorithm is proposed to achieve the optimal solution. The upper layer incorporates an SA-DDQN algorithm with a self-attention mechanism for generating communication decisions (CDs), and the lower layer applies a deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) algorithm to manage power control, task offloading, and resource allocation decisions (PTORADs). This design enables the algorithm to capture inter-vehicle dependencies more effectively, improves convergence stability, and achieves superior in total computational cost.

- To more accurately capture real-world scenarios, considering the time-varying characteristics of the studied model, parameters like vehicle task size, complexity, maximum execution delay, and available computational power for both ICVs and MECs are defined as interval values. We conducted simulation experiments across multiple parameter settings to demonstrate the efficiency and advancement of the presented strategy.

2. Related Works

3. System Model and Problem Formulation

3.1. Task Model

3.2. Communication Model

3.3. Computation Model

3.3.1. Local Computation

3.3.2. Offload Computation

3.3.3. Total Computation Cost

3.4. Problem Formulation

4. HHDRL-Based Task Offloading and Resource Allocation

4.1. Problem Analysis

- Upper layer—CD process: The upper layer agent is utilized to learn how to make optimal communication decisions. The agent observes information such as vehicle distance states, vehicle task status, vehicle and nearby MEC servers’ computing power status, etc. It employs reinforcement learning algorithms to determine offloading decision actions . The task offloading decision of each vehicle will impact the resource allocation decisions in the lower layer.

- Lower layer—PTORAD process: The upper-layer actions act on the environment. Based on the observed changes in system state, the lower layer agent adjusts its actions: , , and . The adjustment aims to enhance the overall reward performance of the actions in both layers. If the offloading decision corresponding to the i-th vehicle is the lower-layer policy treats the corresponding action as an invalid action, set to 0. If , the lower layer generates valid actions.

4.2. HHDRL Framework

4.2.1. States, Actions, and Rewards

4.2.2. SA-DDQN for Discrete Action in Upper Layer

4.2.3. DDPG for Continuous Actions in Lower Layer

4.2.4. Training and Implementation of HHDRL Algorithm

| Algorithm 1: Training process of HHDRL | |

| 1: | Initialize evaluation network parameter and target network parameter of SA-DDQN; |

| 2: | Initialize actor evaluation network parameter and critic evaluation network parameter of DDPG; |

| 3: | Initialize actor target network parameter and critic target network parameter of DDPG; |

| 4: | Initialize the experience replay buffer ; |

| 5: | for episode = 1 to do |

| 6: | Initialize environment, observe the initial system state ; |

| 7: | for to T do |

| 8: | Get the current state ; |

| 9: | Selecting upper communication decision actions based on SA-DDQN; |

| 10: | if then |

| 11: | Selecting lower actions task offloading ratio , communication power , MEC computational power allocation ratio based on DDPG, and ; |

| 12: | else if then |

| 13: | Task offloading ratio , communication power , MEC computational power allocation ratio , and ; |

| 14: | end if |

| 15: | Configure ; |

| 16: | Execute action , obtain reward , and the next state ; |

| 17: | Store into , and remove the oldest tuple when the buffer reaches capacity; |

| 18: | Sample a mini-batch of samples from ; |

| 19: | Obtain Q-value of SA-DDQN according to Equation (24); |

| 20: | Update by Equation (25); and reset periodically; |

| 21: | Obtain Q-value of DDPG and update minimizing the expected loss function of the critic network according to Equation (26); |

| 22: | Update actor evaluation network parameter and critic evaluation network parameter according to Equation (27) and Equation (28) respectively; |

| 23: | Update parameter and by using soft target update; |

| 24: | end for |

| 25: | end for |

4.3. Complexity and Scalability Analysis

4.3.1. Time Complexity Analysis

4.3.2. Space Complexity Analysis

4.3.3. Scalability Analysis

5. Simulation Results and Analysis

5.1. Setting and Benchmarks

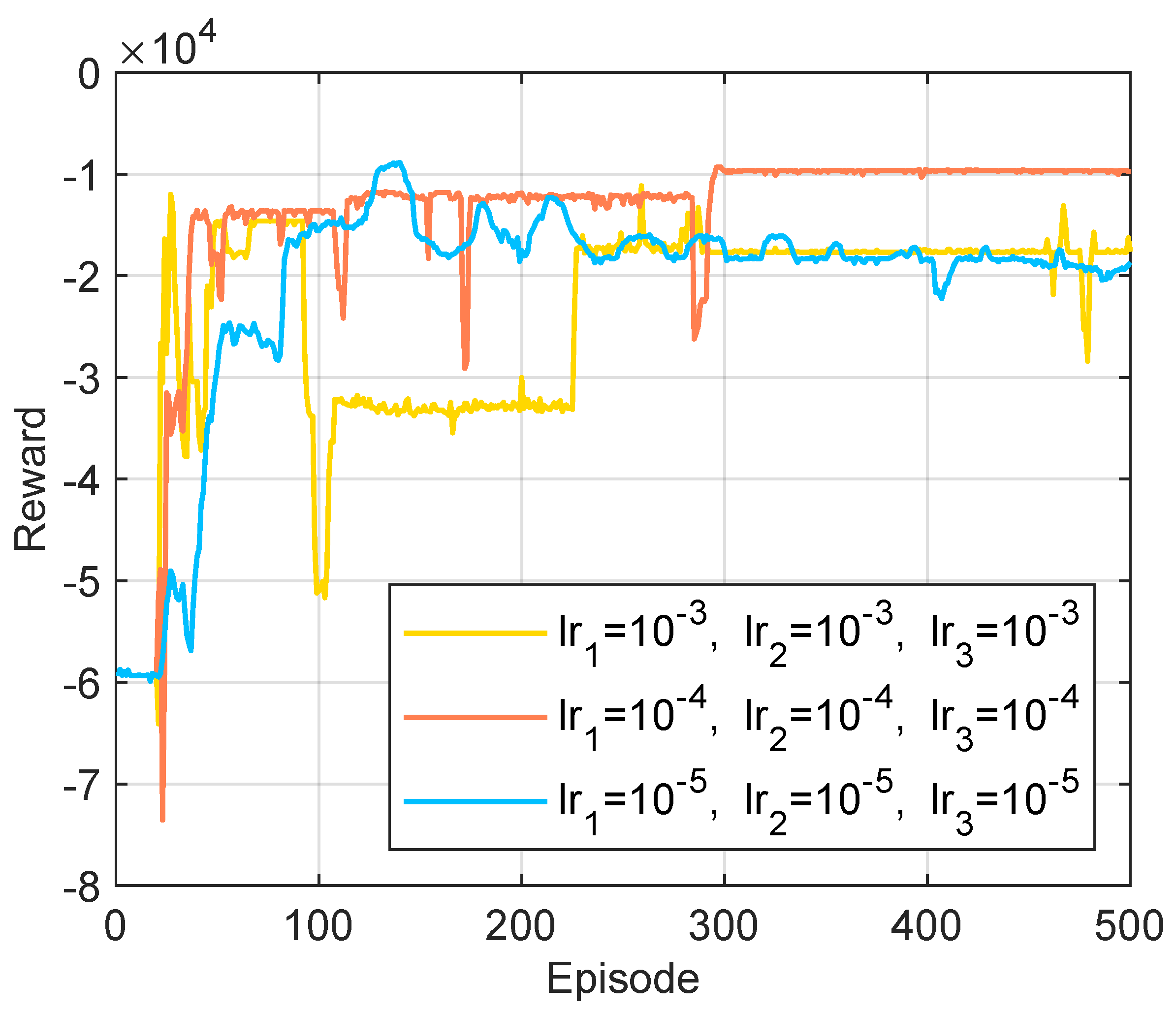

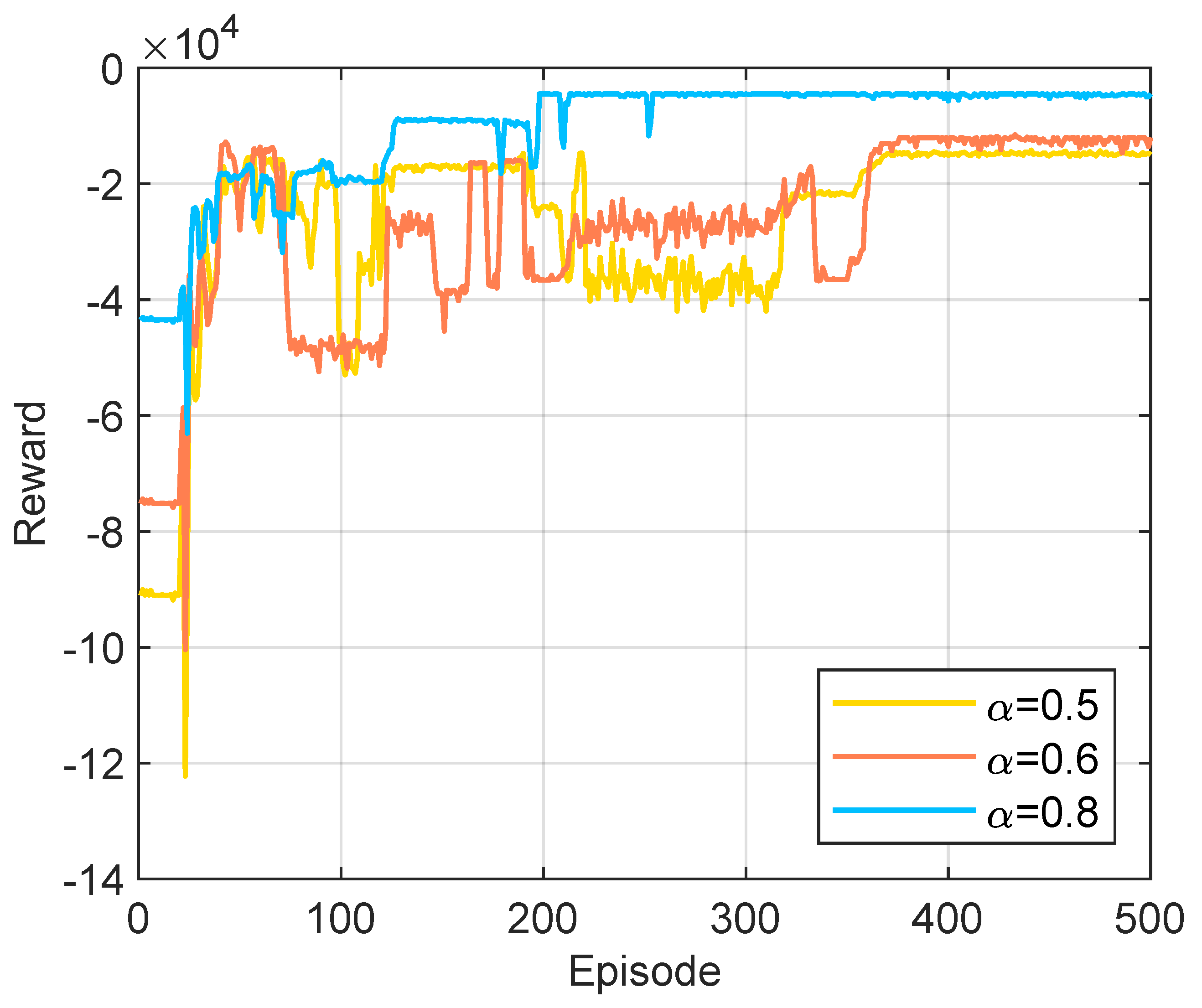

5.2. The Performance of the Proposed Algorithm

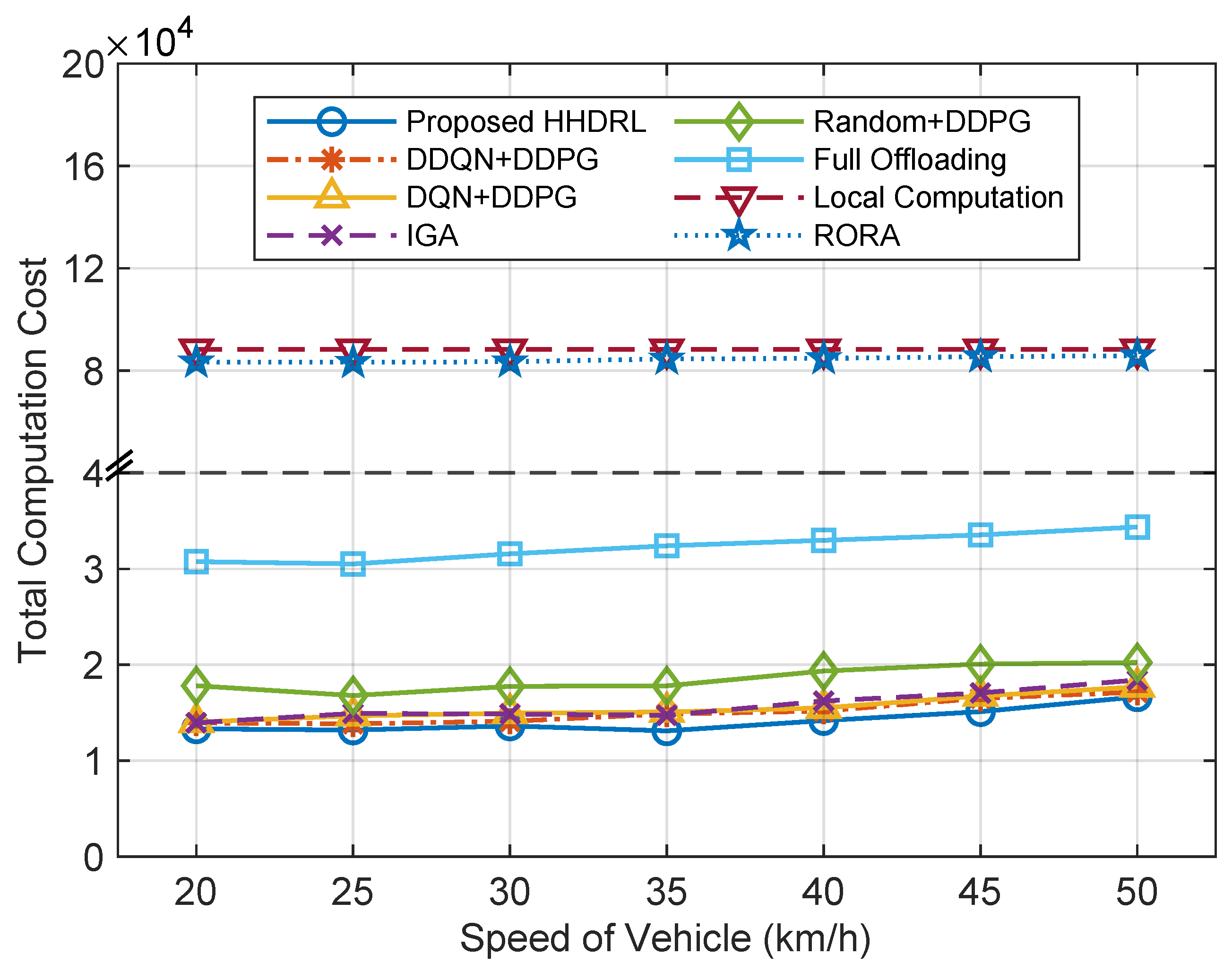

5.3. Comparative Analysis of Simulation Results

5.4. Ablation Study on Network Structures

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICV | Intelligent connected vehicle |

| VECN | Vehicular edge computing network |

| MEC | Mobile edge computing |

| HHDRL | Hybrid hierarchical deep reinforcement learning |

| DDQN | Double deep Q-network |

| DDPG | Deep deterministic policy gradient |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| RSU | Roadside unit |

| VT | Vehicle terminal |

| DRL | Deep reinforcement learning |

| TOSRA | Task offloading scheduling and resource allocation |

| CD | Communication decision |

| PTORADs | Power control, task offloading, and resource allocation decisions |

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

| V2I | Vehicle-to-infrastructure |

| SA-DDQN | Self-attention-enhanced DDQN |

| FCSAN | Fully connected self-attention network |

| DNN | Deep neural network |

| DQN | Deep Q-network |

References

- China Industry Innovation Alliance for the Intelligent and Connected Vehicle (CAICV). White Paper on Vehicle-Road-Cloud Integrated System; China Industry Innovation Alliance for the Intelligent and Connected Vehicle: Beijing, China, 2023; Available online: https://www.digitalelite.cn/h-nd-5740.html (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Shi, W.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Xu, L. Edge Computing: Vision and Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016, 3, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Jia, Y.; Chen, Z.; Nan, Z.; Liang, L. Efficient Task Completion for Parallel Offloading in Vehicular Fog Computing. China Commun. 2019, 16, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, S.; Ali, Z.; Waqas, M.; Tu, S.; Hassan, S.A.; Abbas, G. Cooperative Computational Offloading in Mobile Edge Computing for Vehicles: A Model-Based DNN Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 3376–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Xu, Z. An Adaptive Scheduling Mechanism for Elastic Grid Computing. In Proceedings of the 2009 5th International Conference on Semantics, Knowledge and Grid, Zhuhai, China, 12–14 October 2009; pp. 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Luo, J.; Qiu, C.; Wang, C.; Qiao, Y. Joint Task Offloading and Resources Allocation for Hybrid Vehicle Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 10355–10368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jiang, K.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Leung, V.C.M. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Energy-Efficient Computation Offloading in Mobile-Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 1517–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Yao, Z.; Wu, G.; Li, Y. Distributed Offloading for Cooperative Intelligent Transportation under Heterogeneous Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 16701–16714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tian, M.; Hui, Y.; Cheng, N.; Sun, R.; Yue, W.; Han, Z. On-Demand Environment Perception and Resource Allocation for Task Offloading in Vehicular Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 16001–16016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lv, T.; Lin, Z.; Zeng, J. Energy-Delay Minimization of Task Migration Based on Game Theory in MEC-Assisted Vehicular Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 8175–8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Dong, P.; Kong, X.; Xia, F. A Cooperative Partial Computation Offloading Scheme for Mobile Edge Computing Enabled Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 4804–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Xing, H.; Wang, F.; Lau, V.K.N. Joint Task Offloading and Cache Placement for Energy-Efficient Mobile Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2023, 12, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zeng, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Wan, S. A Multi-hop Task Offloading Decision Model in MEC-Enabled Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 3215–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Peng, J.; Xiong, B.; Huang, J. Adaptive Offloading in Mobile-Edge Computing for Ultra-Dense Cellular Networks Based on Genetic Algorithm. J. Cloud Comput. 2021, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, W.; Sun, J.; Pace, P.; He, L.; Fortino, G. An Efficient Collaborative Task Offloading Approach Based on Multi-Objective Algorithm in MEC-Assisted Vehicular Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 11249–11263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rago, A.; Piro, G.; Boggia, G.; Dini, P. Anticipatory Allocation of Communication and Computational Resources at the Edge Using Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Mobile Users. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2021, 18, 4548–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgkitsis, A.; Mekikis, P.-V.; Antonopoulos, A.; Verikoukis, C. Data Driven Service Orchestration for Vehicular Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 4100–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, G.; Meneghello, F.; Carli, R.; Schenato, L.; Rossi, M. EASE: Energy-Aware Job Scheduling for Vehicular Edge Networks With Renewable Energy Resources. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2023, 7, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Luo, Y.; Liu, A.; Bhuiyan, Z.A.; Zhang, S. Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning for Vehicular Computation Offloading in IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 9763–9773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Sun, H.; Zhuang, Z.; Liao, J.; Yu, F.R. Scalable Parallel Task Scheduling for Autonomous Driving Using Multi-Task Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 13861–13874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Jolfaei, A. Task Offloading Strategy Based on Reinforcement Learning Computing in Edge Computing Architecture of Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 173779–173789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-S.; Lee, S. Resource Allocation for Vehicular Fog Computing Using Reinforcement Learning Combined with Heuristic Information. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 10450–10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Xiang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Dai, H.; Yu, E.; Deng, Q. Task Offloading and Resource Allocation Based on Reinforcement Learning and Load Balancing in Vehicular Networking. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 2217–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Tao, J.; Lui, K.; Zhang, G.; Gao, F. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Joint Optimization of Delay and Privacy in Multiple-User MEC Systems. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2023, 11, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wei, Z.; Feng, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P. Intelligent Computation Offloading for MEC-Based Cooperative Vehicle Infrastructure System: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 7665–7679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Wang, X.; Hu, M.; Ouyang, W.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. DRL-Based Computation Offloading With Queue Stability for Vehicular-Cloud-Assisted Mobile Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 2797–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y. Adaptive Digital Twin and Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning for Vehicular Edge Computing and Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2022, 18, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Liao, W.; Tan, C.; Liu, H.; Zheng, M. DRL-Based Task Offloading and Resource Allocation Strategy for Secure V2X Networking. IEICE Trans. Commun. 2025, E108-B, 1190–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Zhao, J.; Gao, F.; Yu, F. Semi-Distributed Resource Management in UAV-Aided MEC Systems: A Multi-Agent Federated Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 13162–13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, N.; Ni, J.; Yu, F.R.; Leung, V.C.M. Digital Twin-Driven Vehicular Task Offloading and IRS Configuration in the Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 24290–24304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, P.; Yang, X.; Wu, H.; Li, W. An Optimal Reverse Affine Maximizer Auction Mechanism for Task Allocation in Mobile Crowdsensing. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 7475–7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wan, S.; Pei, Q. Distributed Computation Offloading Method Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning in ICV. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 103, 107108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Simeone, O.; Kang, J. Mobile Edge Computing via a UAV-Mounted Cloudlet: Optimization of Bit Allocation and Path Planning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 2049–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ai, B.; Chen, L.; Cui, Y.; Wang, N. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Computation and Communication Resource Allocation in Multiaccess MEC Assisted Railway IoT Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 23797–23808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Huang, K.; Chae, H.; Kim, B.-H. Energy-Efficient Resource Allocation for Mobile-Edge Computation Offloading. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2017, 3, 1397–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Qiu, Y. Latency-Optimal Task Offloading for Mobile-Edge Computing System in 5G Heterogeneous Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 87th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Spring), Porto, Portugal, 3–6 June 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yu, F.R.; Pei, Q.; Chu, X.; Du, J.; Zhu, L. Cooperative Computation Offloading and Resource Allocation for Blockchain-Enabled Mobile-Edge Computing: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 6214–6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, S. RMDDQN-Learning: Computation Offloading Algorithm Based on Dynamic Adaptive Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning in Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 11374–11388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3GPP. Study on LTE-Based V2X Services; TR 36.885, V14.0.0; 3GPP: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhu, H.; Pan, Y.; Wang, J. Latency Minimization for MEC-V2X Assisted Autonomous Vehicles Task Offloading. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 4917–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Bi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Hawbani, A.; Yu, K. Task Optimization Allocation in Vehicle Based Edge Computing Systems With Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2025, 74, 3156–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, N.; Hassan, S.A.; Mahmood, A.; Dev, K.; Do, D.-T.; Gidlund, M. Computation Offloading and Resource Allocation in MEC-Enabled Integrated Aerial-Terrestrial Vehicular Networks: A Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 21478–21491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhang, X. An Efficient Partial Task Offloading and Resource Allocation Scheme for Vehicular Edge Computing in a Dynamic Environment. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 2488–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, Z. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Adaptive Computation Offloading and Power Allocation in Vehicular Edge Computing Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 13339–13349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lu, L.; Li, X. Edge-Cloud Collaborative Task Offloading Mechanism Based on DDQN in Vehicular Networks. Comput. Eng. 2022, 48, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, W.; Ding, Y.; Xiong, N. Computation Offloading Optimization for UAV Assisted Mobile Edge Computing: A Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Approach. Wirel. Netw. 2021, 27, 2991–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| The length of the road L | 1800 m |

| The width of the road W | 15 m |

| The width of each lane H | 3 m |

| The number of lanes Q | 4 |

| The coverage radius of each RSU R | 500 m [40,41,42] |

| The number of ICVs N | [4, 6, 8, 10, 12] |

| The number of MEC servers M | 2 |

| The total time duration T | 8 s |

| The length of each time slot | 0.2 s |

| The maximum execution delay of the offloading task | [0.5, 3] s [7,46] |

| The speed of the i-th ICV | [20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50] km/h |

| The size of the offloading task | [0.5, 2), [2, 3.5), [3.5, 5), [5, 6.5), [6.5, 8), [8, 9.5), [9.5, 11) Mbits [34,43] |

| The computational complexity of the offloading task | [1, 1.5), [1.5, 2), [2, 2.5), [2.5, 3), [3, 3.5), [3.5, 4), [4, 4.5) Gcycles/Mbits [46] |

| The computing capacity of the ICVs | [500, 650), [650, 800)], [800, 950), [950, 1100), [1100, 1250), [1250, 1400), [1400, 1550) MHz [7,43] |

| The available computing resources of MEC servers | [3, 3.5), [3.5, 4), [4, 4.5), [4.5, 5), [5, 5.5), [5.5, 6), [6, 6.5) GHz [34] |

| The maximum power of the j-th MEC server | 90 W |

| The channel gain value per unit reference distance | −50 dB [47] |

| The energy coefficient | [25] |

| The system communication bandwidth B | 2 MHz [25] |

| The power of Gaussian white noise | −100 dBm [47] |

| The transmission loss | 20 dB [47] |

| The maximum communication transmission power | 1 W [25] |

| Algorithm | Average Time (s) |

|---|---|

| Proposed HHDRL | |

| DDQN+DDPG | |

| DQN+DDPG | |

| IGA | |

| Random+DDPG | |

| Full Offloading | |

| Local Computation | |

| RORA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Zou, Y.; Du, G.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J. Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for ICVs in Vehicular Edge Computing Networks Based on Hybrid Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning. Sensors 2025, 25, 6914. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226914

Liu J, Zou Y, Du G, Zhang X, Wu J. Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for ICVs in Vehicular Edge Computing Networks Based on Hybrid Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6914. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226914

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jiahui, Yuan Zou, Guodong Du, Xudong Zhang, and Jinming Wu. 2025. "Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for ICVs in Vehicular Edge Computing Networks Based on Hybrid Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6914. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226914

APA StyleLiu, J., Zou, Y., Du, G., Zhang, X., & Wu, J. (2025). Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for ICVs in Vehicular Edge Computing Networks Based on Hybrid Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning. Sensors, 25(22), 6914. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226914